Abhay R. Satoskar, MD, PhD

Ohio State University

Columbus, Ohio, USA

Gary L. Simon, MD, PhD

Th e George Washington University

Washington DC, USA

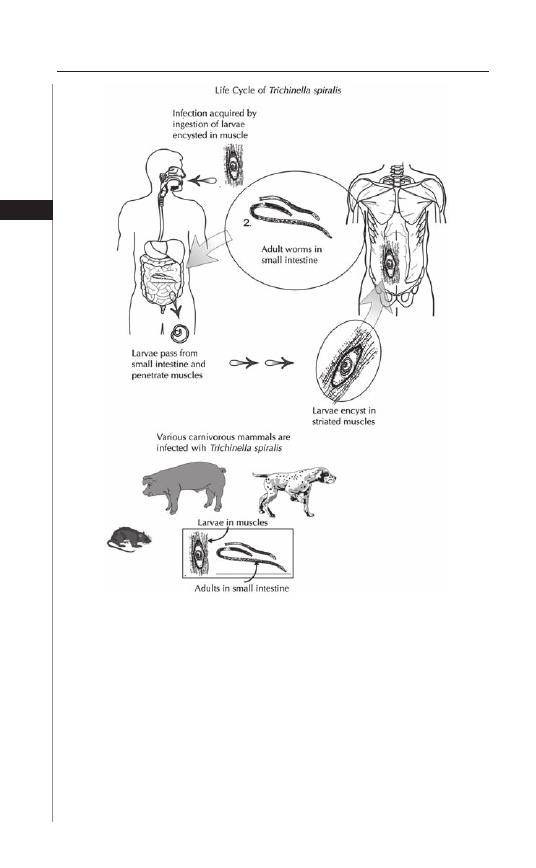

Peter J. Hotez, MD, PhD

Th e George Washington University

Washington DC, USA

Moriya Tsuji, MD, PhD

Th e Rockefeller University

New York, New York, USA

Medical Parasitology

Austin, Texas

U.S.A.

v a d e m e c u m

L A N D E S

B

I

O

S

C

I

E

N

C

E

VADEMECUM

Parasitology

LANDES BIOSCIENCE

Austin, Texas USA

Copyright ©2009 Landes Bioscience

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage

and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed in the USA.

Please address all inquiries to the Publisher:

Landes Bioscience, 1002 West Avenue, Austin, Texas 78701, USA

Phone: 512/ 637 6050; FAX: 512/ 637 6079

ISBN: 978-1-57059-695-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Medical parasitology / [edited by] Abhay R. Satoskar ... [et al.].

p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-57059-695-7

1. Medical parasitology. I. Satoskar, Abhay R.

[DNLM: 1. Parasitic Diseases. WC 695 M489 2009]

QR251.M426 2009

616.9'6--dc22

2009035449

While the authors, editors, sponsor and publisher believe that drug selection and dosage and

the specifi cations and usage of equipment and devices, as set forth in this book, are in accord

with current recommend ations and practice at the time of publication, they make no warranty,

expressed or implied, with respect to material described in this book. In view of the ongoing

research, equipment development, changes in governmental regulations and the rapid accumula-

tion of information relating to the biomedical sciences, the reader is urged to carefully review and

evaluate the information provided herein.

Dedications

To Anjali, Sanika and Monika for their support —Abhay R. Satoskar

To Vicki, Jason and Jessica for their support —Gary L. Simon

To Ann, Matthew, Emily, Rachel, and Daniel —Peter J. Hotez

To Yukiko for her invaluable support —Moriya Tsuji

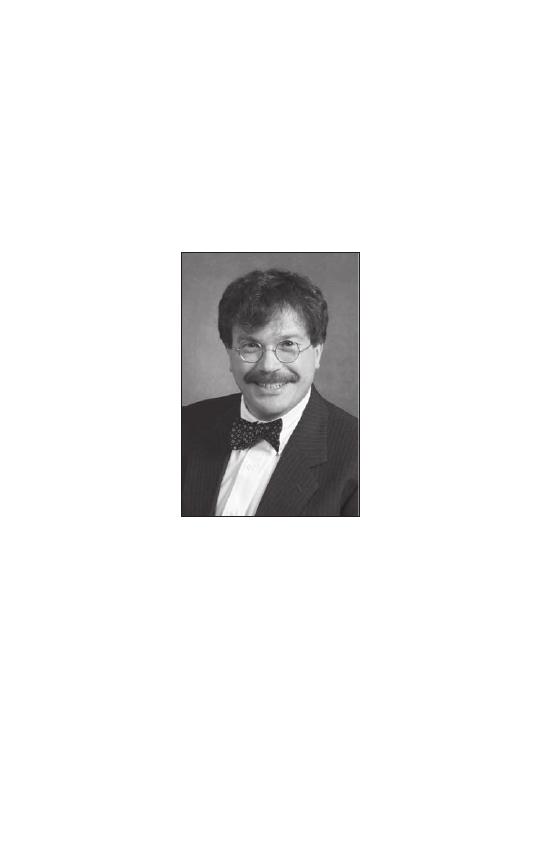

About the Editors...

ABHAY R. SATOSKAR is Associate Professor of Microbiology at the Ohio

State University, Columbus. Main research interests include parasitology and

development of immunotherapeutic strategies for treating parasitic diseases.

He is a member of numerous national and international scientifi c organiza-

tions including American Association of Immunologists and American Society

of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. He has served as a consultant for several

organizations including NIH (USA), National Research Foundation (South

Africa), Wellcome Trust (UK) and Sheikh Hamadan Foundation (UAE).

He holds visiting faculty appointments in institutions in India and Mexico.

Abhay Satoskar received his medical degree (MB, BS and MD) from Seth

G. S. Medical College and King Edward VII Memorial Hospital affi liated to

University of Bombay, India. He received his doctoral degree (PhD) from

University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.

About the Editors...

GARY L. SIMON is the Walter G. Ross Professor of Medicine and

Director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Th e George Washington

University School of Medicine. He is also Vice-Chairman of the Department

of Medicine. Dr. Simon is also Professor of Microbiology, Tropical Medicine

and Immunology and Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. His

research interests are in the diagnosis and treatment of HIV infection and

its complications. He is especially interested in the interaction between HIV

and diseases of sub-Saharan Africa, notably tuberculosis.

Dr. Simon is a native of Brooklyn, New York, but grew up in the Wash-

ington, DC metropolitan area. He obtained his undergraduate degree in

chemistry from the University of Maryland and a PhD degree in physical

chemistry from the University of Wisconsin. He returned to the University

of Maryland where he received his MD degree and did his internal medicine

residency. He did his infectious disease training at Tuft s-New England Medi-

cal Center in Boston.

About the Editors...

PETER J. HOTEZ is Distinguished Research Professor and the Walter G. Ross

Professor and Chair of the Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Tropi-

cal Medicine at Th e George Washington University, where his major research

and academic interest is in the area of vaccine development for neglected tropical

diseases and their control. Prof. Hotez is also the President of the Sabin Vaccine

Institute, a non-profi t medical research and advocacy organization. Th rough the

Institute, Dr. Hotez founded the Human Hookworm Vaccine Initiative, a product

development partnership supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation,

to develop a recombinant vaccine for human hookworm disease, and the Global

Network for Tropical Neglected Diseases Control, a new partnership formed to

facilitate the control of neglected tropical diseases in developing countries. He is

also the Founding Editor-in-Chief of PLoS Tropical Neglected Diseases.

Dr. Hotez is a native of Hartford, Connecticut. He obtained his BA degree in

Molecular Biophysics Phi Beta Kappa from Yale University (1980) and his MD

and PhD from the medical scientist-training program at Weill Cornell Medical

College and Th e Rockefeller University.

About the Editors...

MORIYA TSUJI is Aaron Diamond Associate Professor and Staff Investiga-

tor, HIV and Malaria Vaccine Program at the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research

Center, Th e Rockefeller University, New York. He is also Adjunct Associate

Professor in the Department of Medical Parasitology at New York University

School of Medicine. He is a member of various national and international

scientifi c organizations, including Faculty of 1000 Biology, United States-Israel

Binational Science Foundation, the Center for Scientifi c Review at the National

Institute of Health of the United States Department of Health and Human

Services, the Science Programme at the Wellcome Trust of the United Kingdom,

the French Microbiology Program at the French Ministry of Research and New

Technologies, and the Board of Experts for the Italian Ministry for University

and Research. He is also an editorial board member of the journal Virology:

Research and Treatment. His major research interests are (i) recombinant viral

vaccines against microbial infections, (ii) identifi cation of novel glycolipid-based

adjuvants for HIV and malaria vaccines, and (iii) the protective role of CD1

molecules in HIV/malaria infection. Moriya Tsuji received his MD in 1983 from

Th e Jikei University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan, and in 1987 earned his

PhD in Immunology from the University of Tokyo, Faculty of Medicine.

Contents

Preface

.......................................................................xxi

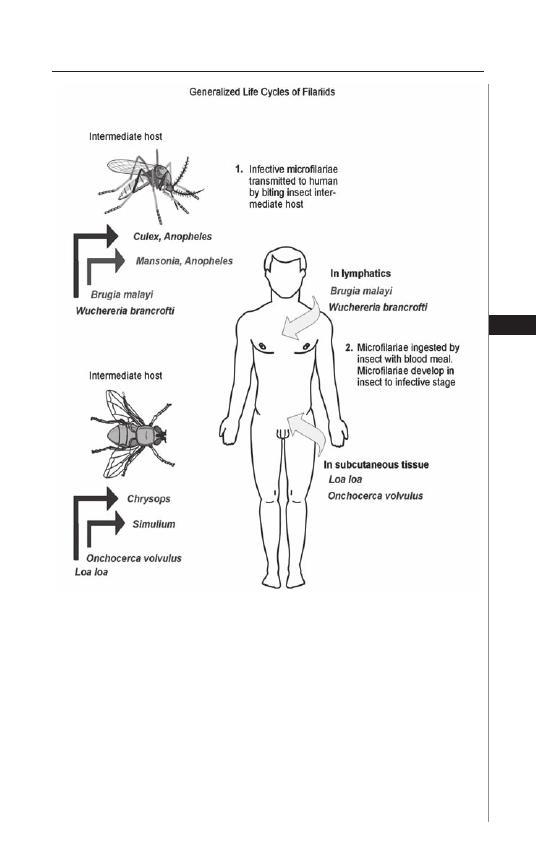

Section I. Nematodes

1.

Enterobiasis.................................................................. 2

Janine R. Danko

2.

Trichuriasis

.................................................................. 8

Rohit Modak

3.

Ascariasis

................................................................... 14

Afsoon D. Roberts

4.

Hookworm

................................................................. 21

David J. Diemert

5.

Strongyloidiasis

.......................................................... 31

Gary L. Simon

6.

Trichinellosis

.............................................................. 39

Matthew W. Carroll

7.

Onchocercosis

............................................................ 45

Christopher M. Cirino

8.

Loiasis

........................................................................ 53

Murliya Gowda

9.

Dracunculiasis

............................................................ 58

David M. Parenti

10. Cutaneous Larva Migrans: “Th e Creeping Eruption” ... 63

Ann M. Labriola

11. Baylisascariasis and Toxocariasis ................................. 67

Erin Elizabeth Dainty and Cynthia Livingstone Gibert

12. Lymphatic Filariasis ................................................... 76

Subash Babu and Th omas B. Nutman

Section II. Trematodes

13. Clonorchiasis and Opisthorchiasis .............................. 86

John Cmar

14. Liver Fluke: Fasciola hepatica ...................................... 92

Michelle Paulson

15. Paragonimiasis ........................................................... 98

Angelike Liappis

16. Intestinal Trematode Infections ................................ 104

Sharon H. Wu, Peter J. Hotez and Th addeus K. Graczyk

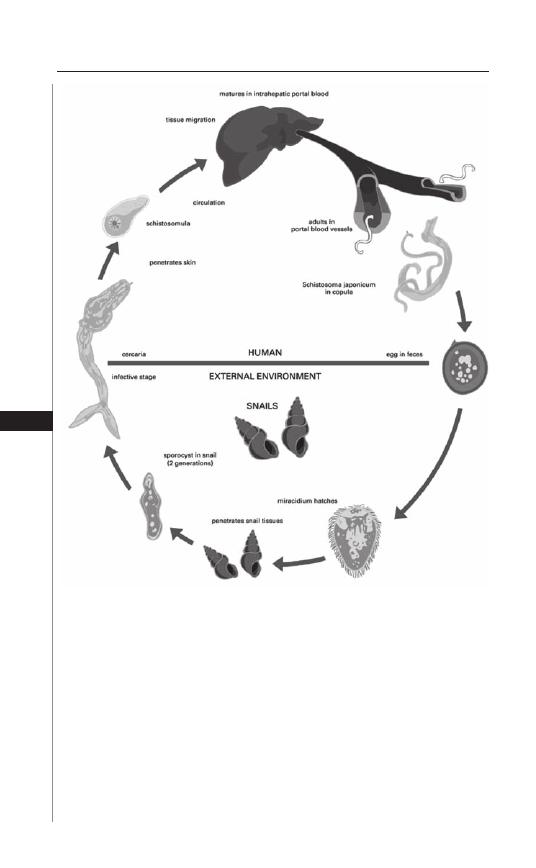

17. Schistosomiasis: Schistosoma japonicum ................... 111

Edsel Maurice T. Salvana and Charles H. King

18. Schistosomiasis: Schistosoma mansoni ...................... 118

Wafa Alnassir and Charles H. King

19. Schistosomiasis: Schistosoma haematobium .............. 129

Vijay Khiani and Charles H. King

Section III. Cestodes

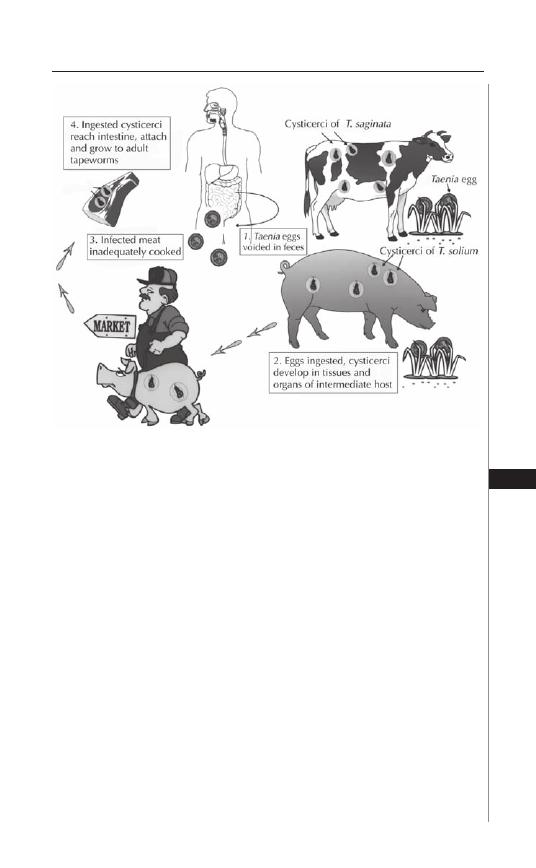

20. Taeniasis and Cyticercosis ........................................ 138

Hannah Cummings, Luis I. Terrazas and Abhay R. Satoskar

21. Hydatid Disease ....................................................... 146

Hannah Cummings, Miriam Rodriguez-Sosa

and Abhay R. Satoskar

Section IV. Protozoans

22. American Trypanosomiasis (Chagas Disease) ........... 154

Bradford S. McGwire and David M. Engman

23. African Trypanosomiasis .......................................... 161

Guy Caljon, Patrick De Baetselier and Stefan Magez

24. Visceral Leishmaniasis (Kala-Azar) ........................... 171

Ambar Haleem and Mary E. Wilson

25. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

.......................................... 182

Claudio M. Lezama-Davila, John R. David

and Abhay R. Satoskar

26. Toxoplasmosis .......................................................... 190

Sandhya Vasan and Moriya Tsuji

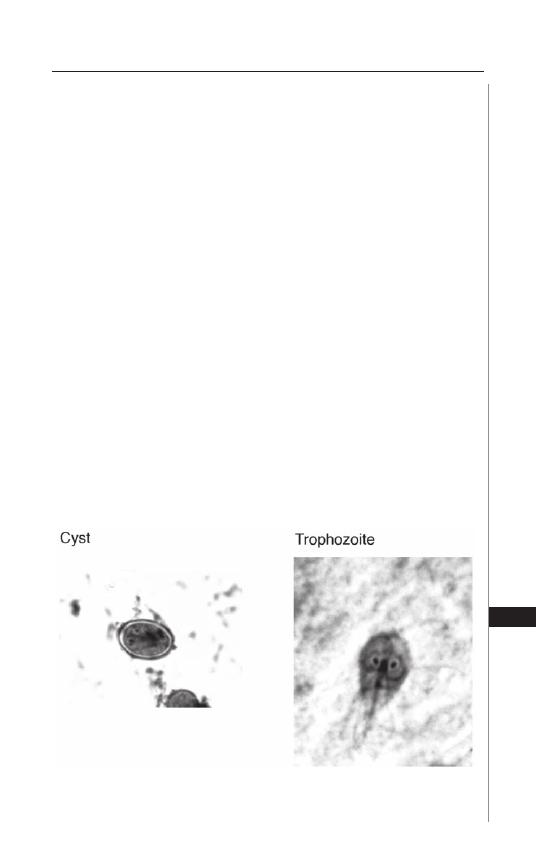

27. Giardiasis ................................................................. 195

Photini Sinnis

28. Amebiasis

................................................................. 206

Daniel J. Eichinger

29. Cryptosporidiosis .................................................... 214

Gerasimos J. Zaharatos

30. Trichomoniasis

......................................................... 222

Raymond M. Johnson

31. Pneumocystis Pneumonia .......................................... 227

Allen B. Clarkson, Jr. and Salim Merali

32. Malaria

..................................................................... 237

Moriya Tsuji and Kevin C. Kain

Section V. Arthropods

33. Clinically Relevant Arthropods ................................ 250

Sam R. Telford III

Appendix

.................................................................. 261

Drugs for Parasitic Infections .......................................................261

Safety of Antiparasitic Drugs .......................................................284

Manufacturers of Drugs Used to Treat Parasitic Infections ...287

Index

........................................................................ 291

Editors

Abhay R. Satoskar, MD, PhD

Department of Microbiology

and

Department of Molecular Virology, Immunology

and Medical Genetics

Ohio State University

Columbus, Ohio, USA

Email: satoskar.2@osu.edu

Chapters 20, 21, 25

Gary L. Simon, MD, PhD

Department of Medicine

and

Department of Microbiology, Immunology

and Tropical Medicine

and

Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

Division of Infectious Diseases

Th e George Washington University

Washington DC, USA

Email: gsimon@mfa.gwu.edu

Chapters 5

Peter J. Hotez, MD, PhD

Department of Microbiology, Immunology

and Tropical Medicine

Th e George Washington University

Washington DC, USA

Email: mtmpjh@gwumc.edu

Chapter 16

Moriya Tsuji, MD, PhD

HIV and Malaria Vaccine Program

Th e Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center

Th e Rockefeller University

New York, New York, USA

Email: mtsuji@adarc.org

Chapters 26, 32

Wafa Alnassir, MD

Department of Medicine

Division of Infectious Diseases

University Hospitals of Cleveland

Cleveland, Ohio, USA

Email: wafanassirali@yahoo.com

Chapter 18

Subash Babu, PhD

Helminth Immunology Section

Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland, USA

Email: sbabu@niaid.nih.gov

Chapter 12

Guy Caljon, PhD

Unit of Cellular and Molecular

Immunology

Department of Molecular and Cellular

Interactions

VIB, Vrije Universiteit Brussel

Brussels, Belgium

Email: gucaljon@vub.ac.be

Chapter 23

Matthew W. Carroll, MD

Division of Infectious Diseases

Th e George Washington University

School of Medicine

Washington DC, USA

Email: mcarroll@gwu.edu

Chapter 6

Christopher M. Cirino, DO, MPH

Division of Infectious Diseases

Th e George Washington University

School of Medicine

Washington DC, USA

Email: ccirino710@hotmail.com

Chapter 7

Allen B. Clarkson, Jr, PhD

Department of Medical Parasitology

New York University

School of Medicine

New York, New York, USA

Email: clarka01@med.nyu.edu

Chapter 31

John Cmar, MD

Department of Medicine

Divisions of Infectious Diseases

and Internal Medicine

Sinai Hospital of Baltimore

Baltimore, Maryland, USA

Email: doc.operon@gmail.com

Chapter 13

Hannah Cummings, BS

Department of Microbiology

Ohio State University

Columbus, Ohio, USA

Email: cummings.123@osu.edu

Chapters 20, 21

Erin Elizabeth Dainty, MD

Department of Obstetrics

and Gynecology

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

Email: erin.dainty@uphs.upenn.edu

Chapter 11

Janine R. Danko, MD, MPH

Department of Infectious Diseases

Uniformed Services University

of the Health Sciences

Naval Medical Research Center

Bethesda, Maryland, USA

Email: janine.danko@med.navy.mil

Chapter 1

Contributors

John R. David, MD

Department of Immunology

and Infectious Diseases

Harvard School of Public Health

Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Email: jdavid@hsph.harvard.edu

Chapter 25

Patrick De Baetselier, PhD

Unit of Cellular and Molecular

Immunology

Department of Molecular and Cellular

Interactions

VIB, Vrije Universiteit Brussel

Brussels, Belgium

Email: pdebaets@vub.ac.be

Chapter 23

David J. Diemert, MD

Human Hookworm Vaccine Initiative

Albert B. Sabin Vaccine Institute

Washington DC, USA

Email: david.diemert@sabin.org

Chapter 4

Daniel J. Eichinger, PhD

Department of Medical Parasitology

New York University

School of Medicine

New York, New York, USA

Email: eichid01@med.nyu.edu

Chapter 28

David M. Engman, MD, PhD

Departments of Pathology

and Microbiology-Immunology

Northwestern University

Chicago, Illinois, USA

Email: d-engman@northwestern.edu

Chapter 22

Cynthia Livingstone Gibert, MD

Department of Medicine

Division of Infectious Diseases

Th e George Washington University

Washington VA Medical Center

Washington DC, USA

Email: cynthia.gibert@med.va.gov

Chapter 11

Murliya Gowda, MD

Infectious Disease Consultants (IDC)

Fairfax, Virginia, USA

Email: pgowda2000@yahoo.com

Chapter 8

Th addeus K. Graczyk, MSc, PhD

Department of Environmental

Health Sciences

Division of Environmental

Health Engineering

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg

School of Public Health

Baltimore, Maryland, USA

Email: tgraczyk@jhsph.edu

Chapter 16

Ambar Haleem, MD

Department of Internal Medicine

University of Iowa

Iowa City, Iowa, USA

Email: ambar-haleem@uiowa.edu

Chapter 24

Raymond M. Johnson, MD, PhD

Department of Medicine

Indiana University School of Medicine

Indianapolis, Indiana, USA

Email: raymjohn@iupui.edu

Chapter 30

Kevin C. Kain, MD, FRCPC

Department of Medicine

University of Toronto

Department of Global Health

McLaughlin Center for Molecular

Medicine

and

Center for Travel and Tropical

Medicine

Toronto General Hospital

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Email: kevin.kain@uhn.on.ca

Chapter 32

Vijay Khiani, MD

Department of Medicine

University Hospitals of Cleveland

Cleveland, Ohio, USA

Email: vijay.khiani@gmail.com

Chapter 19

Charles H. King, MD, FACP

Center for Global Health and Diseases

Case Western Reserve University

School of Medicine

Cleveland, Ohio, USA

Email: chk@cwru.edu

Chapters 17-19

Ann M. Labriola, MD

Department of Medicine

Division of Infectious Diseases

Th e George Washington University

Washington VA Medical Center

Washington DC, USA

Email: ann.labriola@va.gov

Chapter 10

Claudio M. Lezama-Davila, PhD

Department of Microbiology

and

Department of Molecular Virology,

Immunology and Medical Genetics

Ohio State University

Columbus, Ohio, USA

Email: lezama-davila.1@osu.edu

Chapter 25

Angelike Liappis, MD

Departments of Medicine

and Microbiology, Immunology

and Tropical Medicine

Division of Infectious Diseases

Th e George Washington University

Washington DC, USA

Email: mtmapl@gwumc.edu

Chapter 15

Stefan Magez, PhD

Unit of Cellular and Molecular

Immunology

Department of Molecular and Cellular

Interactions

VIB, Vrije Universiteit Brussel

Brussels, Belgium

Email: stemagez@vub.ac.be

Chapter 23

Bradford S. McGwire, MD, PhD

Division of Infectious Diseases

and

Center for Microbial Interface Biology

Ohio State University

Columbus, Ohio, USA

Email: brad.mcgwire@osumc.edu

Chapter 22

Salim Melari, PhD

Department of Biochemistry

Fels Institute for Cancer Research

and Molecular Biology

Temple University School of Medicine

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

Email: salim.merali@temple.edu

Chapter 31

Rohit Modak, MD, MBA

Division of Infectious Diseases

Th e George Washington University

Medical Center

Washington DC, USA

Email: Rohitmodak@yahoo.com

Chapter 2

Th omas B. Nutman, MD

Helminth Immunology Section

Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland, USA

Email: tnutman@niaid.nih.gov

Chapter 12

David M. Parenti, MD, MSc

Department of Medicine

and

Department of Microbiology,

Immunology and Tropical Medicine

Division of Infectious Diseases

Th e George Washington University

Washington DC, USA

Email: dparenti@mfa.gwu.edu

Chapter 9

Michelle Paulson, MD

National Institute of Allergy

and Infectious Diseases

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland, USA

Email: paulsonm@niaid.nih.gov

Chapter 14

Afsoon D. Roberts, MD

Department of Medicine

and

Department of Microbiology,

Immunology and Tropical Medicine

Division of Infectious Diseases

Th e George Washington University

School of Medicine

Washington DC, USA

Email: aroberts@mfa.gwu.edu

Chapter 3

Miriam Rodriguez-Sosa, PhD

Unidad de Biomedicina

FES-Iztacala

Universidad Nacional Autómonia

de México

México

Email: rodriguezm@campus.iztacala.

unam.mx

Chapter 21

Edsel Maurice T. Salvana, MD

Department of Medicine

Division of Infectious Diseases

University Hospitals of Cleveland

Cleveland, Ohio, USA

Email: edsel.salvana@case.edu

Chapter 17

Photini Sinnis, MD

Department of Medicine

and

Department of Medical Parasitology

New York University School of

Medicine

New York, New York, USA

Email: photini.sinnis@med.nyu.edu

Chapter 27

Sam R. Telford, III, SD, MS

Department of Biomedical Sciences

Infectious Diseases

Tuft s University School

of Veterinary Medicine

Graft on, Massachusetts, USA

Email: sam.telford@tuft s.edu

Chapter 33

Luis I. Terrazas, PhD

Unidad de Biomedicina

FES-Iztacala

Universidad Nacional Autónoma

de México

México

Email: literrazas@campus.iztacala.

unam.mx

Chapter 20

Sandhya Vasan, MD

Th e Aaron Diamond AIDS

Research Center

Th e Rockefeller University

New York, New York, USA

Email: svasan@adarc.org

Chapter 26

Mary E. Wilson, MD, PhD

Departments of Internal Medicine,

Microbiology and Epidemiology

Iowa City VA Medical Center

University of Iowa

Iowa City, Iowa, USA

Email: mary-wilson@uiowa.edu

Chapter 24

Sharon H. Wu, MS

Department of Microbiology,

Immunology and Tropical Medicine

Th e George Washington University

Washington DC, USA

Email: sharonwu@gwu.edu

Chapter 16

Gerasimos J. Zaharatos, MD

Division of Infectious Diseases,

Department of Medicine

and

Department of Microbiology

Jewish General Hospital

McGill University

Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Email: gerasimos.zaharatos@mcgill.ca

Chapter 29

Preface

Infections caused by parasites are still a major global health problem.

Although parasitic infections are responsible for a signifi cant morbidity and

mortality in the developing countries, they are also prevalent in the developed

countries. Early diagnosis and treatment of a parasitic infection is not only

critical for preventing morbidity and mortality individually but also for reduc-

ing the risk of spread of infection in the community. Th is concise book gives

an overview of critical facts for clinical and laboratory diagnosis, treatment

and prevention of parasitic diseases which are common in humans and which

are most likely to be encountered in a clinical practice. Th is book is a perfect

companion for primary care physicians, residents, nurse practitioners, medical

students, paramedics, other public health care personnel and as well as travel-

ers. Th e editors would like to thank all the authors for their expertise and their

outstanding contributions. We would also like to thank Dr. Ronald Landes

and all other staff of Landes Bioscience who has worked tirelessly to make this

magnifi cent book possible.

Abhay R. Satoskar, MD, PhD

Gary Simon, MD, PhD

Moriya Tsuji, MD, PhD

Peter J. Hotez, MD, PhD

S

ECTION

I

Nematodes

Chapter 1

Medical Parasitology, edited by Abhay R. Satoskar, Gary L. Simon, Peter J. Hotez

and Moriya Tsuji. ©2009 Landes Bioscience.

Enterobiasis

Janine R. Danko

Background

Enterobius vermicularis, commonly referred to as pinworm, has the largest

geographical distribution of any helminth. Discovered by Linnaeus in 1758, it was

originally named Oxyuris vermicularis and the disease was referred to as oxyuriasis

for many years. It is believed to be the oldest parasite described and was recently

discovered in ancient Egyptian mummifi ed human remains as well as in DNA

samples from ancient human coprolite remains from North and South America.

Enterobius is one of the most prevalent nematodes in the United States and in

Western Europe. At one time, in the United States there are an estimated 42 million

infected individuals. It is found worldwide in both temperate and tropical areas.

Prevalence is highest among the 5-10 year-old age group and infection is uncom-

mon in children less than two years old. Enterobiasis has been reported in every

socioeconomic level; however spread is much more likely within families of infected

individuals, or in institutions such as child care centers, orphanages, hospitals and

mental institutions. Humans are the only natural host for the parasite.

Infection is facilitated by factors including overcrowding, wearing soiled cloth-

ing, lack of adequate bathing and poor hand hygiene, especially among young

school-aged children. Infestation follows ingestion of eggs which usually reach

the mouth on soiled hands or contaminated food. Transmission occurs via direct

anus to mouth spread from an infected person or via airborne eggs that are in the

environment such as contaminated clothing or bed linen. Th e migration of worms

out of the gastrointestinal tract to the anus can cause local perianal irritation and

pruritus. Scratching leads to contamination of fi ngers, especially under fi ngernails

and contributes to autoinfection. Finger sucking and nail biting may be sources of

recurrent infection in children. Spread within families is common. E. vermicularis

may be transmitted through sexual activity, especially via oral and anal sex.

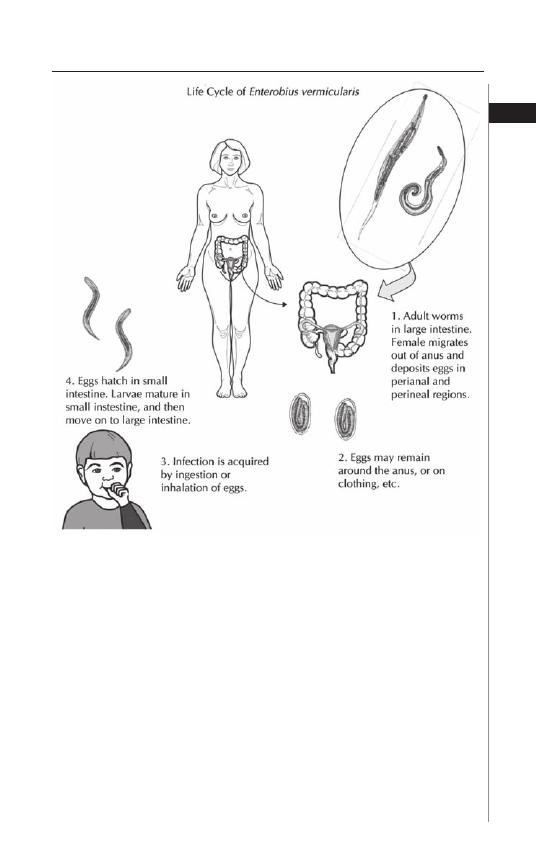

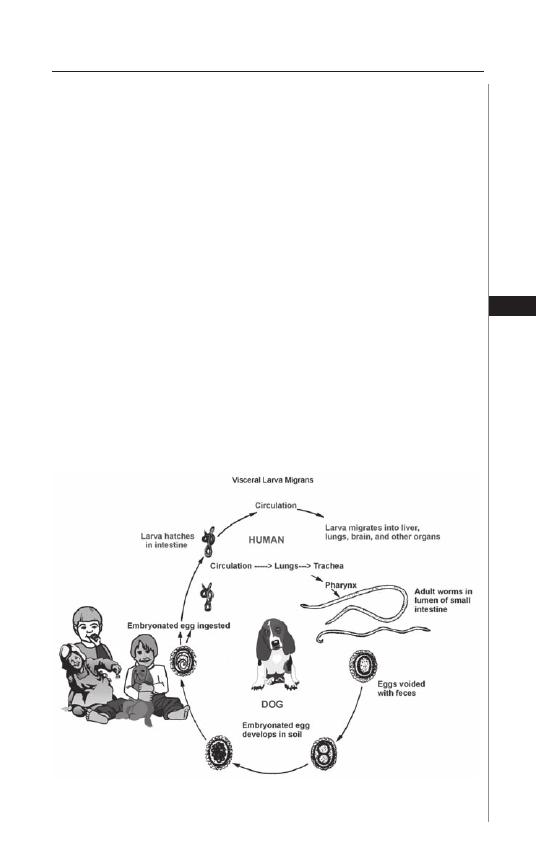

When swallowed via contaminated hands, food or water, the eggs hatch releasing

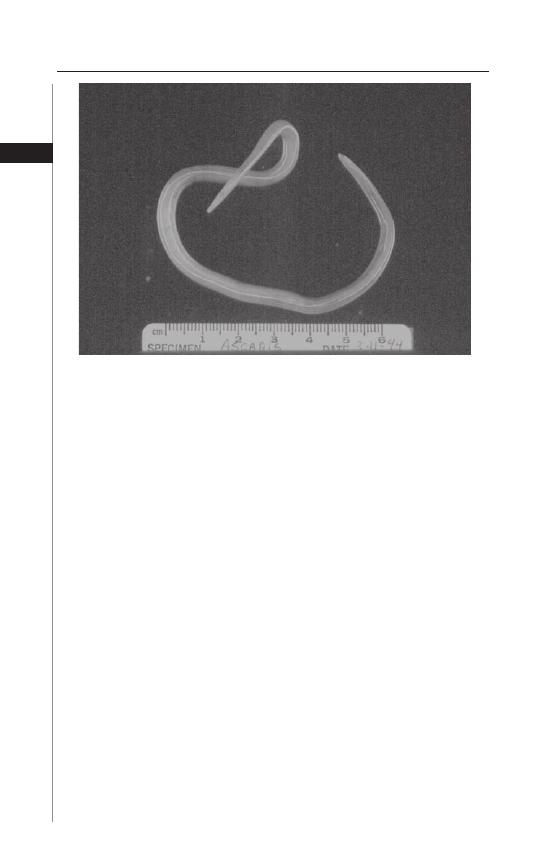

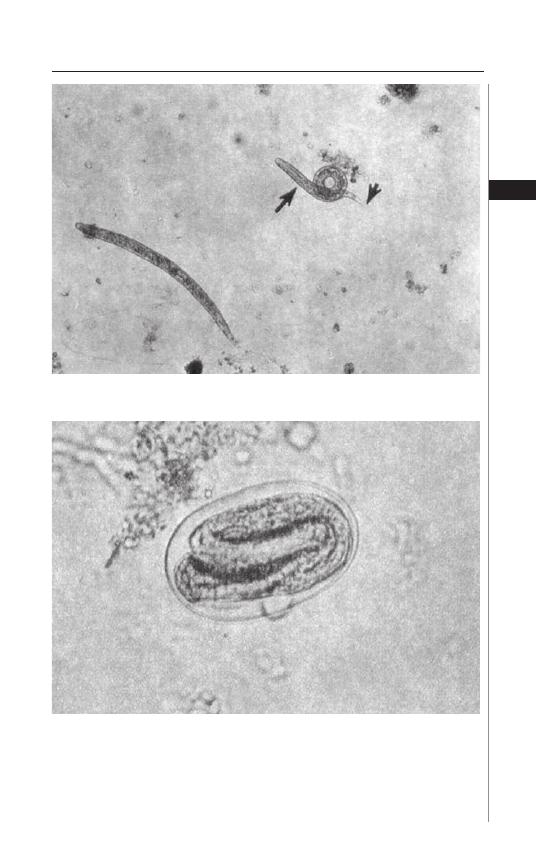

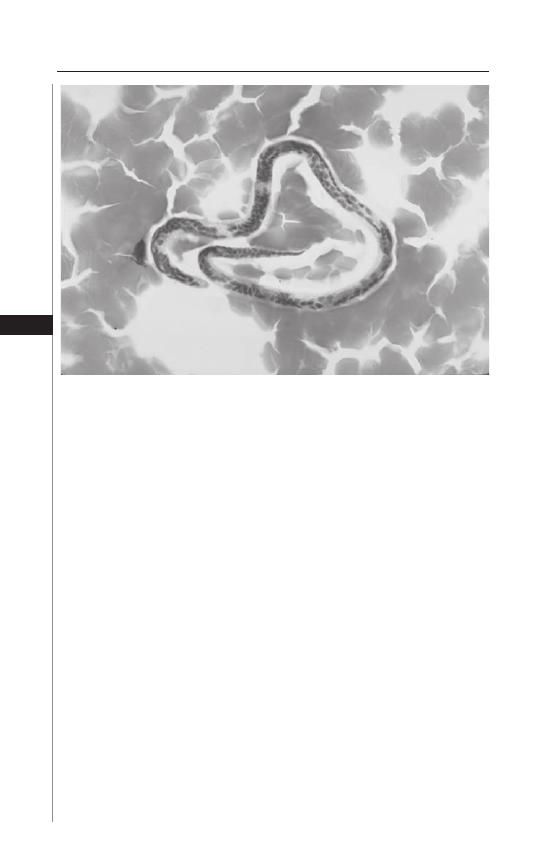

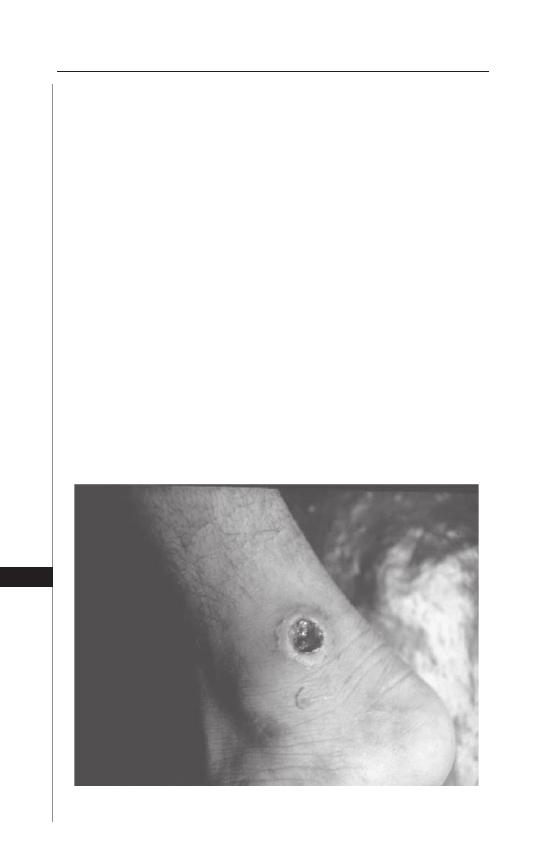

larvae (Fig. 1.1). Th e larvae develop in the upper small intestine and mature in 5 to

6 weeks without undergoing any further migration into other body cavities (i.e.,

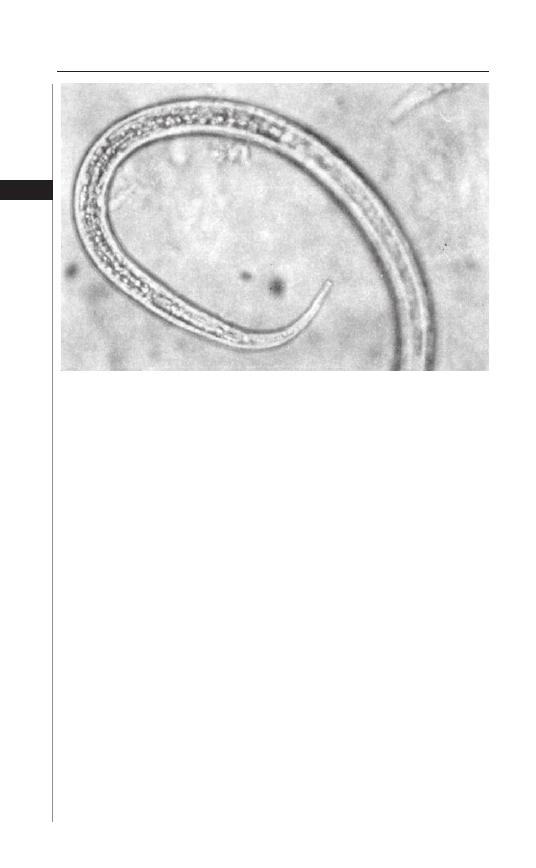

lungs). Both male and female forms exist. Th e smaller male is 2-5 mm in length and

0.3 mm in diameter whereas the female is 8-13 mm long and up to 0.6 mm in di-

ameter (Fig. 1.2). Copulation occurs in the distal small bowel and the adult females

settle in the large intestine where they can survive for up to 13 weeks (males live for

approximately 7 weeks). Th e adult female can produce approximately 11,000 eggs.

A gravid female can migrate out through the anus to lay her eggs. Th is phenomenon

usually occurs at night and is thought to be secondary to the drop in host body

3

Enterobiasis

1

temperature at this time. Th e eggs embyonate and become infective within 6 hours

of deposition. In cool, humid climates the larvae can remain infective for nearly 2

weeks, but under warm, dry conditions, they begin to lose their infectivity within

2 days. Most infected persons harbor a few to several hundred adult worms.

Disease Signs and Symptoms

Th e majority of enterobiasis cases are asymptomatic; however the most common

symptom is perianal or perineal pruritus. Th is varies from mild itching to acute

pain. Symptoms tend to be most troublesome at night and, as a result, infected

individuals oft en report sleep disturbances, restlessness and insomnia. Th e most

common complication of infection is secondary bacterial infection of excoriated

skin. Folliculitis has been seen in adults with enterobiasis.

Gravid female worms can migrate from the anus into the female genital tract.

Vaginal infections can lead to vulvitis, serous discharge and pelvic pain. Th ere are

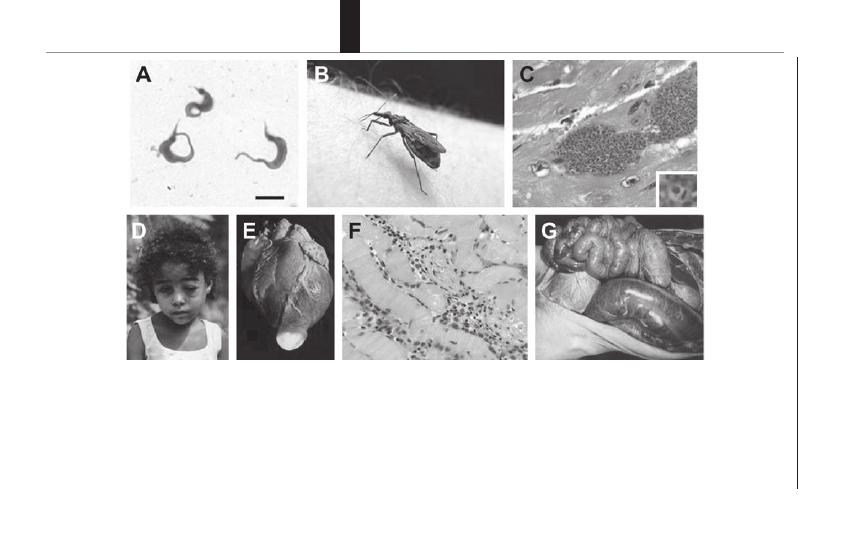

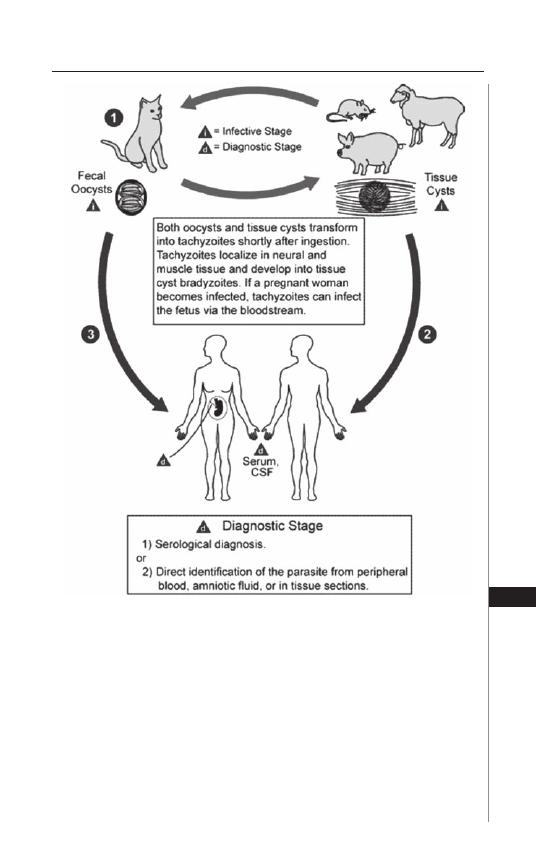

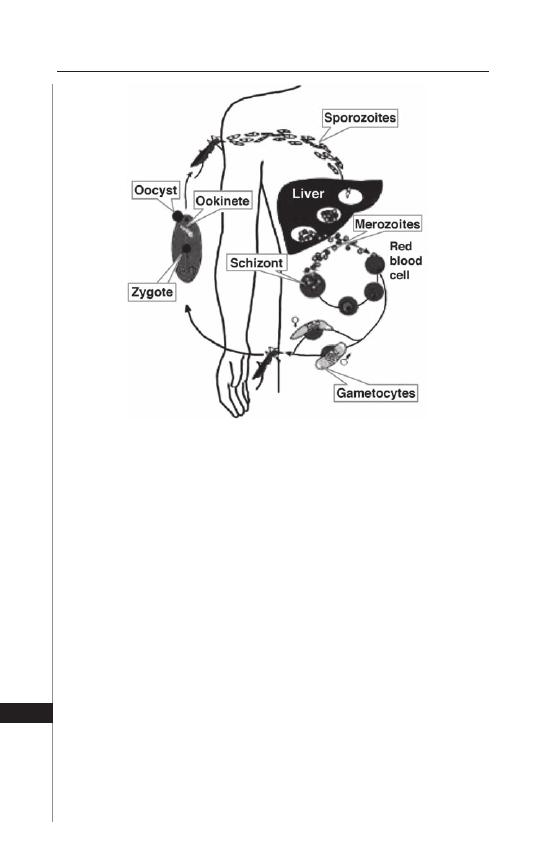

Figure 1.1. Life-cycle of Enterobius vermicularis. Reproduced from: Nappi

AJ, Vass E, eds. Parasites of Medical Importance. Austin: Landes Bioscience,

2002:84.

4

Medical Parasitology

1

numerous reports of granulomas in the vaginal wall, uterus, ovary and pelvic peri-

toneum caused by E. vermicularis dead worms or eggs. Pre-pubertal and adolescent

girls with E. vermicularis infection can develop vulvovaginitis. Scratching may lead

to introital colonization with colonic bacteria and thus may increase susceptibility

to urinary tract infections.

Although ectopic lesions due to E. vermicularis are rare, pinworms can also

migrate to other internal organs, such as the appendix, the prostate gland, lungs

or liver, the latter being a result of egg embolization from the colon via the portal

venous system. Within the colonic mucosa or submucosa granulomas can be

uncomfortable and may mimic other diseases such as carcinoma of the colon or

Crohn’s disease. E. vermicularis has been found in the lumen of uninfl amed ap-

pendices in patients who have been operated on for acute appendicitis. Although

eosinophilic colitis has been described with enterobiasis, eosinophilia is uncommon

in infected individuals.

Diagnosis

Th e diagnosis of E. vermicularis infestation rests on the recognition of dead

adult worms or the characteristic ova. In the perianal region, the adult female

worm may be visualized as a small white “piece of thread”. Th e most successful

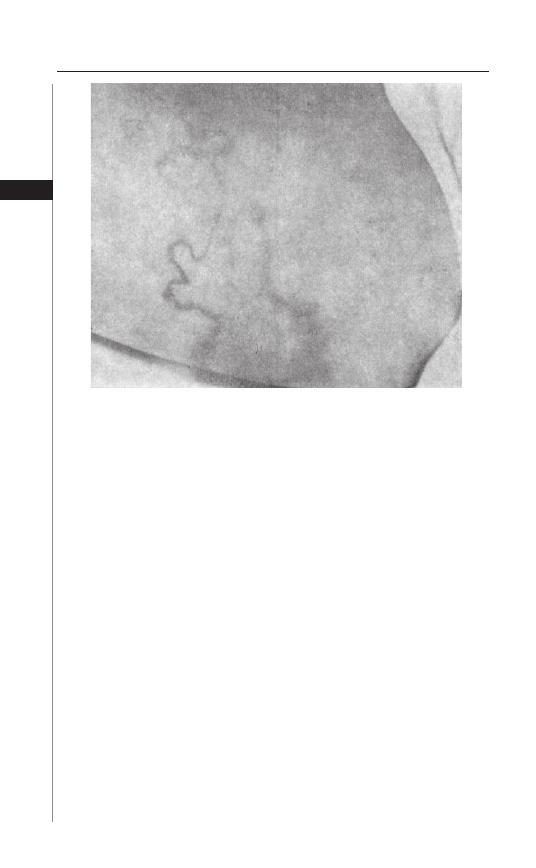

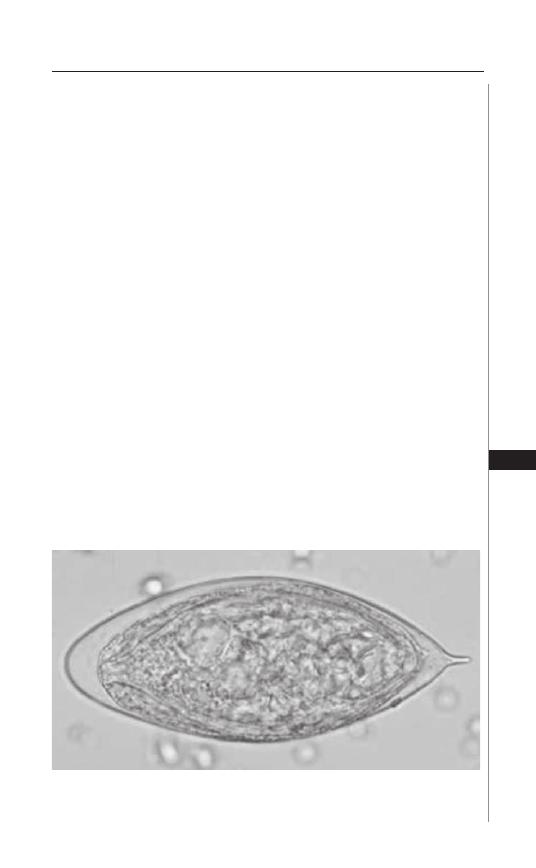

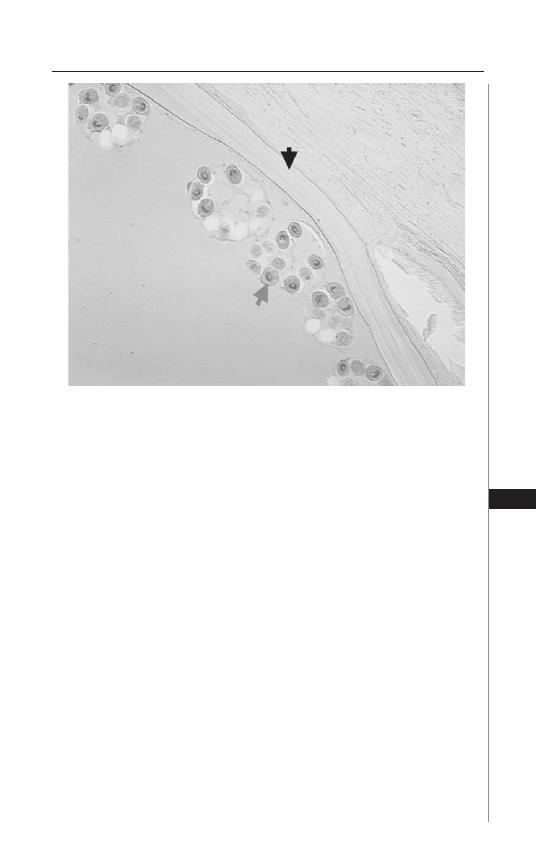

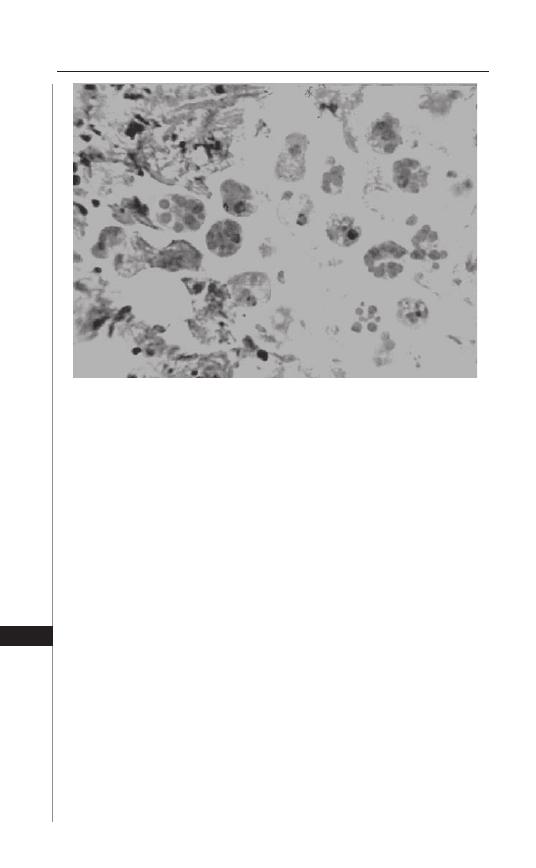

diagnostic method is the “Scotch tape” or “cellophane tape” method (Fig. 1.3).

Th is is best done immediately aft er arising in the morning before the individual

defecates or bathes. Th e buttocks are spread and a small piece of transparent or

cellulose acetate tape is pressed against the anal or perianal skin several times.

Th e strip is then transferred to a microscope slide with the adhesive side down.

Th e worms are white and transparent and the skin is transversely striated. Th e

egg is also colorless, measures 50-54 × 20-27 mm and has a characteristic shape,

Figure 1.2. Enterobius vermicularis.

5

Enterobiasis

1

fl attened on one side. Examination of a single specimen detects approximately

50% of infections; when this is done on three consecutive mornings sensitivity

rises to 90%. Parija et al. found a higher sensitivity if lacto-phenol cotton blue

stain was used in detecting eggs aft er the tape test was performed. Six consecu-

tive negative swabs on separate days are necessary to exclude the diagnosis. Stool

examination for eggs is usually not helpful, as only 5-15% of infected persons

will have positive results. Rarely, E. vermicularis eggs have been found in cervi-

cal specimens (done for routine Papanicolaou smears), in the urine sediment,

or the worms have been seen during colonoscopy. Serologic tests specifi c for E.

vermicularis are not available.

Treatment

E. vermicularis is susceptible to several anthelmintic therapies, with a cure rate

of >90%. Mebendazole (100 mg), albendazole (400 mg), or pyrantel pamoate

(11 mg/kg of base) given as a single dose and then repeated aft er 14 days are all

eff ective regimens. Mebendazole or albendazole are preferred because they have

relatively few side eff ects. Th eir mode of action involves inhibition of the micro-

tubule function in adult worms and glycogen depletion. For children less than 2,

200 mg should be administered. Although equally eff ective, pyrantel pamoate is

associated with more side eff ects including gastrointestinal distress, neurotoxicity

and transient increases in liver enzymes. Both mebendazole and albendazole are

category C drugs, thus contraindicated in pregnancy although an Israeli study by

Diav-Citrin et al of 192 pregnant women exposed to mebendazole, failed to reveal

an increase in the number of malformations or spontaneous abortions compared

to the general population.

Persons with eosinophilic colitis should be treated for

three successive days with mebendazole (100 mg twice daily). Experience with

Figure 1.3. Enterobius vermicularis captured on scotch tape.

6

Medical Parasitology

1

mebendazole or albendazole with ectopic enterobiasis is limited; persons who

present with pelvic pain, those who have salpingitis, tuboovarian abscesses or

painful perianal granulomas or signs or symptoms of appendicitis oft en proceed

to surgery. In most reported cases, the antiparasitic agent is given aft er surgery

when the diagnosis of pinworm has been established. Conservative therapy with

local or systemic antibiotics is usually appropriate for perianal abscesses due to

enterobiasis. Ivermectin has effi cacy against pinworm but is generally not used for

this indication and is not approved for enterobiasis in the United States. Overall,

prognosis with treatment is excellent. Because pinworm is easily spread throughout

households, the entire family of the infected person should be treated. All bedding

and clothing should be thoroughly washed. Th e same rule should be applied to

institutions when an outbreak of pinworm is discovered.

Prevention and Prophylaxis

Th ere are no eff ective prevention or prophylaxis strategies available. Although

mass screening campaigns and remediation for parasite infection is costly, treatment

of pinworm infection improves the quality of life for children. Th e medications,

coupled with improvements in sanitation, especially in rural areas can provide a

cost-eff ective way at treating this nematode infection. Measures to prevent rein-

fection and spread including clipping fi ngernails, bathing regularly and frequent

hand washing, especially aft er bowel movements. Routine laundering of clothes

and linen is adequate to disinfect them. House cleaning should include vacuum-

ing around beds, curtains and other potentially contaminated areas to eliminate

other environmental eggs if possible. Health education about route of infection,

especially autoinfection and these prevention tactics should always be incorporated

into any treatment strategy.

Disclaimer

Th e views expressed in this chapter are those of the author and do not neces-

sarily refl ect the offi cial policy or position of the Department of the US Navy, the

Department of Defense or the US Government.

I am a military service member (or employee of the US Government). Th is

work was prepared as part of my offi cial duties. Title 17 USC §105 provides that

‘Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United

States Government.’ Title 17 USC §101 defi nes a US Government work as a work

prepared by a military service member or employee of the US Government as part

of that person’s offi cial duties. —Janine R. Danko

Suggested Reading

1. Al-Rufaie HK, Rix GH, Perez Clemente MP et al. Pinworms and postmenopausal

bleeding. J Clin Path 1998; 51:401-2.

2. Arca MJ, Gates RL, Groner JL et al. Clinical manifestations of appendiceal

pinworms in children: an institutional experience and a review of the literature.

Pediatr Surg Int 2004; 20:372-5.

3. Beaver PC, Kriz JJ, Lau TJ. Pulmonary nodule caused by Enterobium vermicularis.

Am J Trop Med Hyg 1973; 22:711-13.

4. Bundy D, Cooper E. In: Strickland GT, ed. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and

Emerging Infectious Diseases, 8th Edition. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company,

2000.

7

Enterobiasis

1

5. Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Arnon J et al. Pregnancy outcome aft er gestational

exposure to mebendazole: a prospective controlled cohort study. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2003; 188:282-5.

6. Fernandez-Flores A, Dajil S. Enterobiasis mimicking Crohn’s disease. Indian J

Gastroenterol 2004; 23:149-50.

7. Georgiev VS. Chemotherapy of enterobiasis. Exp Opin Pharmacother 2001;

2:267-75.

8. Goncalves ML, Araujo A, Ferreira LF. Human intestinal parasites in the past: New

fi ndings and a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2003; 98:103-18.

9. Herrstrom P, Fristrom A, Karlsson A et al. Enterobius vermicularis and fi nger

sucking in young Swedish children. Scand. J Prim Healthcare 1997; 115:146-8.

10. Little MD, Cuello CJ, D’Allessandra A . Granuloma of the liver due to Enterobius

vermicularis: report of a case. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1973; 22:567-9.

11. Liu LX, Chi J, Upton MP. Eosinophilic colitis associated with larvae of the pin-

worm Enterobius vermicularis. Lancet 1995; 346:410-12.

12. Neva FA, Brown HW. Basic Clinical P, 6th Edition. Norwalk: Appleton and Lange,

1994.

13. Parija SC, Sheeladevi C, Shivaprakash MR et al. Evaluation of lacto-phenol

cotton blue stain for detection of eggs of Enterobius vermicularis in perianal surface

samples. Trop Doctor 2001; 31:214-5.

14. Petro M, Iavu K, Minocha A. Unusual endoscopic and microscopic view of

E. vermicularis: a case report with a review of the literature. South Med Jrnl 2005;

98:927-9.

15. Smolyakov R, Talalay B, Yanai-Inbar I et al. Enterobius vermicularis infection of

the female genital tract: a report of three cases and review of the literature. Eur J

Obstet Gynecol Reproduct Biol 2003; 107:220-2.

16. Sung J, Lin R, Huang L et al. Pinworm control and risk factors of pinworm

infection among primary-school chdilren in Taiwan. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2001;

65:558-62.

17. Tornieporth NG, Disko R, Brandis A et al. Ectopic enterobiasis: a case report and

review. J Infect 1992; 24:87-90.

18. Wagner ED, Eby WC. Pinworm prevalence in California elementary school

children and diagnostic methods. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1983; 32:998-1001.

Medical Parasitology, edited by Abhay R. Satoskar, Gary L. Simon, Peter J. Hotez

and Moriya Tsuji. ©2009 Landes Bioscience.

Trichuriasis

Rohit Modak

Background

Trichuris trichiura is an intestinal nematode aff ecting an estimated 795

million persons worldwide. Also known as whipworm due to its characteristic

shape, Trichuris can be classifi ed as a soil-transmitted helminth because its life cycle

mandates embryonic development of its eggs or larvae in the soil. It is the second

most common nematode found in humans, behind Ascaris.

Trichuriasis is more common in areas with tropical weather such as Asia,

Sub-Sarahan Africa and the Americas, particularly in impoverished regions of

the Caribbean. It is also more common in poor rural communities and areas that

lack proper sanitary facilities with easily contaminated food and water. A large

number of individuals who are infected actually harbor fewer than 20 worms

and are asymptomatic; those with a larger burden of infection (greater than 200

worms) are most likely to develop clinical disease. School age children tend to be

most heavily infected.

Th ere is no reservoir host for Trichuris. Transmission occurs when contaminated

soil reaches the food, drink, or hands of a person and is subsequently ingested.

Th erefore, poor sanitary conditions is a major risk factor. It is noteworthy that

patients are oft en coinfected with other soil-transmitted helminths like Ascaris

and hookworm due to similar transmission modalities.

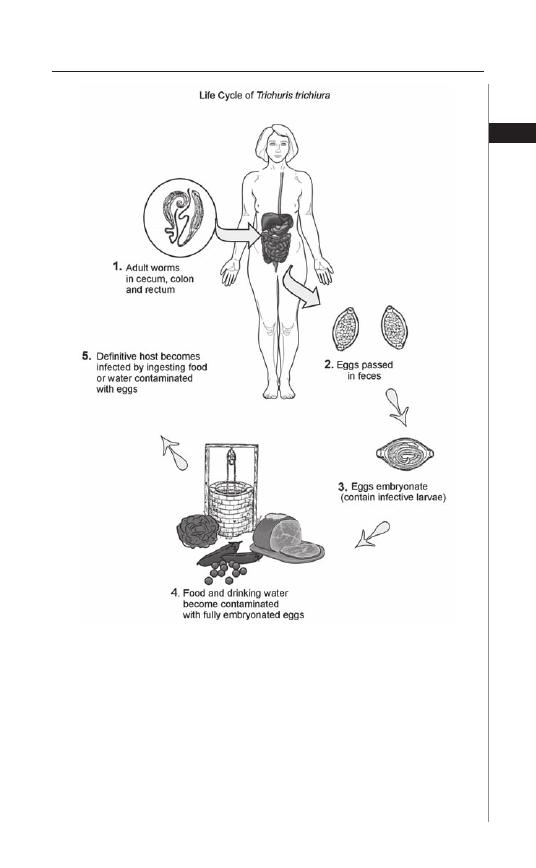

Life Cycle

Adult female worms shed between 3,000 to 20,000 eggs per day, which are

passed with the stool. In the soil, the eggs develop into a 2-cell stage, an advance

cleavage stage and then embryonate. It is the embryonated egg that is actually

infectious. Environmental factors such as high humidity and warm temperature

quicken the development of the embryo. Th is helps explain the geographic

predilection for tropical environments. Under optimal conditions, embryonic

development occurs between 15-30 days. Infection begins when these embryo-

nated eggs are ingested.

Th e eggs fi rst hatch in the small intestine and release larvae that penetrate the

columnar epithelium and situate themselves just above the lamina propria. Aft er

four molts, an immature adult emerges and is passively carried to the large intestine.

Here, it re-embeds itself into the colonic columnar cells, usually in the cecum and

ascending colon. Heavier burdens of infection spread to the transverse colon and

rectum. Th e worm creates a syncytial tunnel between the mouths of crypts; it is

here that the narrow anterior portion is threaded into the mucosa and its thicker

C

HAPTER

2

posterior end protrudes into the lumen, allowing its eggs to escape. Maturation

and mating occur here as well.

Th e pinkish gray adult worm is approximately 30-50 mm in length, with the

female generally being slightly larger than the male. Th e nutritional requirements of

Trichuris are unclear; unlike hookworm however, it does not appear that Trichuris is

dependent on its host’s blood. Eggs are fi rst detectable in the feces of those infected

about 60-90 days following ingestion of the embryonated eggs. Th e life span of an

adult worm is about one to three years. Unlike Ascaris and hookworm, there is no

migratory phase through the lung.

9

Trichuriasis

2

Figure 2.1. Life Cycle of Trichuris Trichura. Reproduced from: Nappi AJ, Vass E,

eds. Parasites of Medical Importance. Austin: Landes Bioscience, 2002:73.

Disease Signs and Symptoms

Frequently, infection with Trichuris is asymptomatic or results only in peripheral

eosinophilia. Clinical disease most oft en occurs in children, as it is this population

that tends to be most heavily-infected and presents as Trichuris colitis. In fact, this is

the most common and major disease entity associated with infection. Acutely, some

patients will develop Trichuris dysentery syndrome, characterized by abdominal

pain and diarrhea with blood and mucus. With severe dysentery, children develop

weight loss and become emaciated. Anemia is common and results from both

mucosal bleeding secondary to capillary damage and chronic infl ammation. Th e

anemia of trichuriasis is not as severe as that seen with hookworm. Trichuris infec-

tion of the rectum can lead to mucosal swelling. In that case, tenesmus is common

and if prolonged can lead to rectal prolapse, especially in children. Adult worms

can be seen on the prolapsed mucosa.

Chronic trichuriasis oft en mimics infl ammatory bowel disease. Physical symp-

toms include chronic malnutrition, short stature and fi nger clubbing. Th ese symp-

toms are oft en alleviated with appropriate anthelminthic treatment. Rapid growth

spurts have been reported in children following deworming with an anthelminthic

agent. Defi cits in the cognitive and intellectual development of children have also

been reported in association with trichuriasis.

Host Response

Infection with Trichuris results in a low-grade infl ammatory response that

is characterized by eosinophilic infi ltration of the submucosa. Th ere is an active

humoral immune response to Trichuris infection, but it is not fully protective.

Like hookworm infections, anthelminthic therapy in endemic areas provides only

10

Medical Parasitology

2

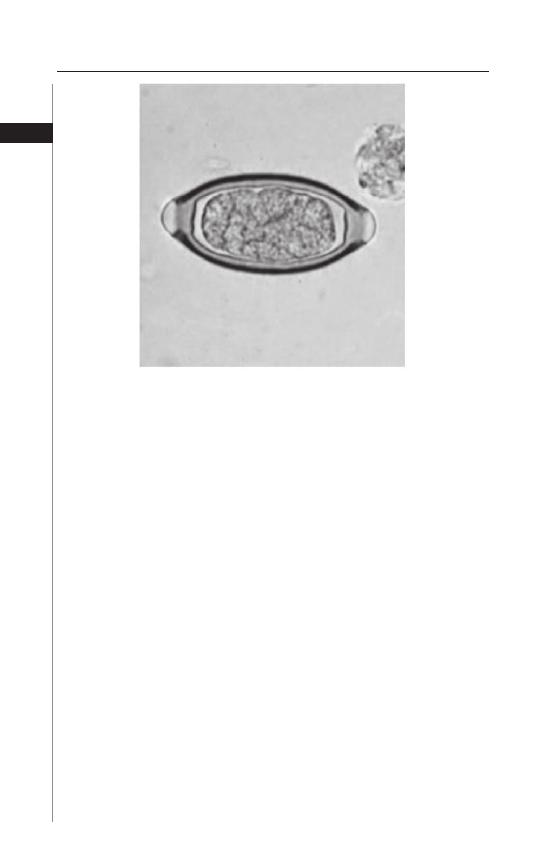

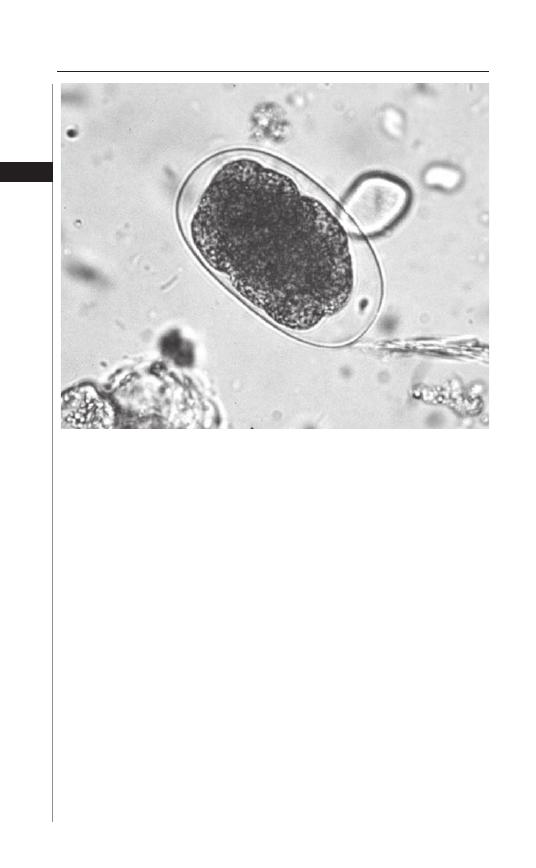

Figure 2.2. Egg of Trichuris trichiura. Reproduced from: Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC) (http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/DPDx/).

transient relief and reexposure to contaminated soil leads to reinfection. Th e T-cell

immune response to Trichuris infection is primarily a Th 2 response. Th is suggests

that trichuriasis, like other nematode infections, has modest immunomodulatory

eff ects.

Diagnosis

Infection can be diagnosed by microscopic identifi cation of Trichuris eggs in

feces. Th e eggs are quite characteristic, with a barrel or lemon shape, thick shell

and a clear plug at each end.

Because the level of egg output is high (200 eggs/g feces per worm pair), a

simple fecal smear is usually suffi cient for diagnosis. However in light infections,

a concentration procedure is recommended.

Trichuriasis can also be diagnosed by identifying the worm itself on the mucosa

of a prolapsed rectum or during colonoscopy. Th e female of the species is generally

longer, while the male has a more rounded appearance.

Because of the frequency of co-infections, a search for other protozoa, specifi -

cally Ascaris and hookworm should be considered. Charcot-Leyden crystals in the

stool in the absence of eggs in the stool should lead to further stool examinations

for T. trichuria. Although infl ammatory bowel disease is oft en in the diff erential,

the sedimentation rate (ESR) is generally not elevated in trichuriasis and the degree

of infl ammation evident on colonoscopic examination is much less than that seen

with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis.

Treatment

Benzimidazoles are the drugs of choice in treating trichuriasis. Th eir anthelm-

inthic activity is primarily due to their ability to inhibit microtubule polymeriza-

tion by binding to beta-tubulin, a protein unique to invertebrates. A single dose

of albendazole has been suggested for treatment; however, despite the appeal of

adequate single dose therapy, clinical studies have shown a cure rate of less than 25

percent. Longer duration of therapy, resulting in higher cure rates, is recommended

for heavier burdens of infection. High cure rates are diffi cult to establish because

of the constant re-expsoure to the organisms. Mebendazole at a dose of 100 mg

twice daily for three days is also eff ective, with cure rates of almost 90 percent. In

some countries, pyrantel-oxantel is used for treatment, with the oxantel compo-

nent having activity against Trichuris and the pyrantel component having activity

against Ascaris and hookworm.

Albendazole and mebendazole are generally well tolerated when given at doses

used to treat trichuriasis, even in pediatric populations. Adverse eff ects include

transient abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea and dizziness. With long-term use,

reported toxicities include bone marrow suppression, alopecia and hepatotox-

icity. Both drugs are not recommended in pregnancy, as they have been shown to

be teratogenic and embryotoxic in laboratory rats. However, albendazole should

be considered in pregnant women in the second or third trimester when the

potential benefi t outweighs the risks to the fetus. Although these drugs have not

been studied in very young children, the World Health Organization (WHO) has

recommended that both agents may be used for treatment in patients as young as

12 months, albeit at reduced dosages.

11

Trichuriasis

2

Prevention and Prophylaxis

Drinking clean water, properly cleaning and cooking food, hand washing

and wearing shoes are the most eff ective means of preventing soil-transmitted

helminth infections. Adequately sanitizing areas in which trichuriasis is prevalent

is extremely problematic; these communities oft en lack the resources needed for

such a substantial undertaking.

Direct exposure to sunlight for greater than 12 hours or temperatures exceed-

ing 40 degrees C in excess of 1 hour kills the embryo within the egg, but under

optimal conditions of moisture and shade in the warm tropical and subtropical soil,

Trichuris eggs can remain viable for months. Th ere is relative resistance to chemical

disinfectants and eggs can survive for prolonged periods even in treated sewage.

Th erefore, proper disposal of sewage is vital to control this infection. In areas of the

world where human feces is used as fertilizer, this is practically impossible.

Because the prevalence of trichuriasis has been estimated to be up to 80% in

some communities and can frequently be asymptomatic, the WHO advocates

empiric treatment of soil-transmitted helminths by administering anthelminthic

drugs to populations at risk. Specifi cally, WHO recommends periodic treatment

of school-aged children, the population in whom the burden of infection is great-

est. Th e goal of therapy is to maintain the individual worm burden at a level less

than that needed to cause signifi cant morbidity or mortality. Th is strategy has

been used successfully in preventing and reversing malnutrition, iron-defi ciency

anemia, stunted growth and poor school performance. Th is is in large part due to

the effi cacy and broad spectrum activity of a single dose of anthelminthic drugs

like albendazole. Because reinfection is a common problem as long as poor sanitary

conditions remain, it is proposed that single dose therapy be given at regular inter-

vals (1-3 times per year). Th e WHO hopes that by 2010, 75% of all school-aged

children at risk for heavy infection will have received treatment.

Major challenges to controlling the infection include continued poor sanitary

conditions. Additionally, the use of benzimidazole drugs at regular intervals may

lead to the emergence of drug resistance. Resistance has been documented in live-

stock and suspected in humans. Since the single dose regimen is not ideal (although

the most feasible), continued monitoring and screening is necessary.

Suggested Reading

1. Adams VJ, Lombard CJ, Dhansay MA et al. Effi cacy of albendazole against the

whipworm Trichuris trichiura: a randomised, controlled trial. S Afr Med J 2004;

94:972-6.

2. Albonico M, Crompton DW, Savioli L. Control strategies for intestinal nematode

infections. Adv Parasito 1999; 42:277-341.

3. Albonico M, Bickle Q, Haji HJ et al. Evaluation of the effi cacy of pyrantel-oxantel

for the treatment of soil-transmitted nematode infections. Trans R Soc Trop Med

Hyg 2002; 96:685-90.

4. Belding D. Textbook of Parasitology. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts,

1965:397-8.

5. Cooper ES. Bundy DAP: Trichuris is not trivial. Parasitol Today 1988; 4:301-5.

6. De Silva N. Impact of mass chemotherapy on the morbidity due to soil-transmitted

nematodes. Acta Tropica 2003; 86:197-214.

7. de Silva NR, Brooker S, Hotez PJ et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections:

updating the global picture. Trends Parasitol 2003; 19:547-51.

12

Medical Parasitology

2

13

Trichuriasis

2

8. Despommier DD, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ et al, eds. Parasitic Diseases, 5th Edition.

New York: Apple Trees Productions, LLC, 2005:110-5.

9. Division of Parasitic Diseases, National Centers for Infectious Diseases, Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: [http://www.dpd.cdc.

gov/DPDx/].

10. Geerts S, Gryseels B. Anthelminthic resistance in human helminthes: a review.

Trop Med Int Health 2001; 6:915-21.

11. Gilman RH, Chong YH, Davis C et al. Th e adverse consequences of heavy Trichuris

infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1983; 77:432-8.

12. Lin AT, Lin HH, Chen CL. Colonoscopic diagnosis of whip-worm infection.

Hepato-Gastroenterol 1998; 45:2105-9.

13. Legesse M, Erko B, Medhin G. Comparative effi cacy of albendazole and three

brands of mebendazole in the treatment of ascariasis and trichuriasis. East Afr

Med J 2004; 81:134-8.

14. MacDonald TT, Choy MY, Spencer J et al. Histopathology and immunohisto-

chemistry of the caecum in children with the Trichuris dysentery syndrome. J Clin

Pathol 1991; 44:194-9.

15. Maguire J. Intestinal Nematodes. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s Principles

and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 6th Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier,

2005:3263-4.

16. Montresor A, Awasthi S, Crompton DWT. Use of benzimadazoles in children

younger than 24 months for the treatment of soil-transmitted helminthiases. Acta

Tropica 2003; 86:223-32.

17. Sirivichayakul C, Pojjaroen-Anant C, Wisetsing P et al. Th e eff ectiveness of 3, 5,

or 7 days of albendazole for the treatment of Trichuris trichiura infection. Ann

Trop Med Parasitol 2003; 97:847-53.

C

HAPTER

3

Medical Parasitology, edited by Abhay R. Satoskar, Gary L. Simon, Peter J. Hotez

and Moriya Tsuji. ©2009 Landes Bioscience.

Ascariasis

Afsoon D. Roberts

Introduction

Ascariasis, a soil-transmitted infection, is the most common human helminthic

infection. Current estimates indicate that more than 1.4 billion people are infected

worldwide. In the United States, there are an estimated 4 million people infected,

primarily in the southeastern states and among immigrants. Th e etiologic agent,

Ascaris lumbricoides, an intestinal roundworm, is the largest nematode to infect

humans. Th e adult worm lives in the small intestine and can grow to a length of

more than 30 cm. Th e female worms are larger than the males. Important fac-

tors associated with an increased prevalence of disease include socio-economic

status, defecation practices and cultural diff erences relating to personal and food

hygiene as well as housing and sewage systems. Most infections are subclinical;

more severe complications occur in children who tend to suff er from the highest

worm burdens.

Epidemiology and Transmission

Th ere are a number of factors that contribute to the high frequency of infec-

tion with Ascaris lumbricoides. Th ese include its ubiquitous distribution, the high

number of eggs produced by the fecund female parasite and the hardy nature of the

eggs which enables them to survive unfavorable conditions. Th e eggs can survive

in the absence of oxygen, live for 2 years at 5-10º C and be unaff ected by dessica-

tion for 2 to 3 weeks. In favorable conditions of moist, sandy soil, they can survive

for up to 6 years, even in freezing winter conditions. Th e greatest prevalence of

disease is in tropical regions, where environmental conditions support year round

transmission of infection. In dry climates, transmission is seasonal and occurs most

frequently during the rainy months.

Ascariasis is transmitted primarily by ingestion of contaminated food or water.

Although infection occurs in all age groups, it is most common in preschoolers and

young children. Sub-optimal sanitation is an important factor, leading to increased

soil and water contamination. In the United States, improvements in sanitation and

waste management have led to a dramatic reduction in the prevalence of disease.

Recently, patterns of variation in the ribosomal RNA of Ascaris worms isolated

in North America were compared to those of worms and pigs from other worldwide

locations. Although repeats of specifi c restriction sites were found in most parasites

from humans and pigs in North America, they were rarely found in parasites from

elsewhere. Th is evidence suggests that perhaps human infections in North America

may be related to Ascaris suum.

15

Ascariasis

3

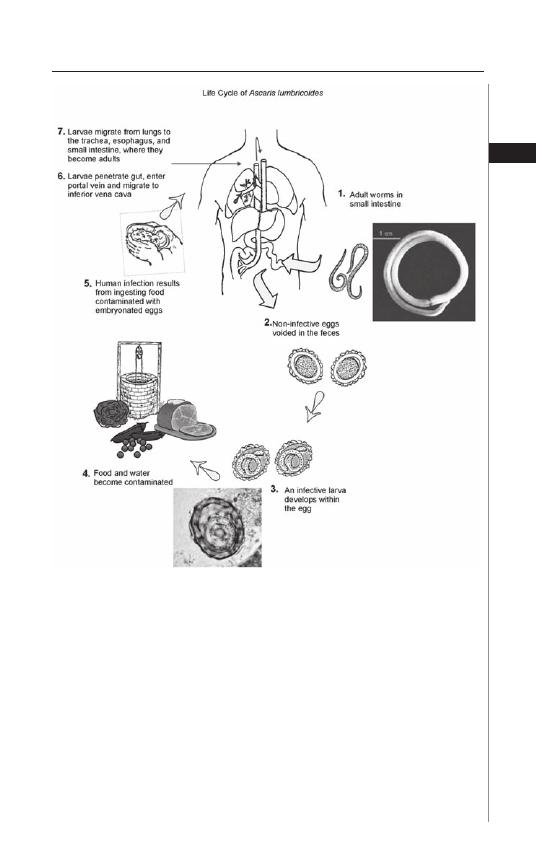

Life Cycle

Th e adult ascaris worms reside in the lumen of the small intestine where

they feed on predigested food (Fig. 3.1). Th eir life span ranges from 10 to 24

months. Th e adult worms are covered with a tough shell composed of collagens

and lipids. Th is outer covering helps protect them from being digested by in-

testinal hydrolases. Th ey also produce protease inhibitors that help to prevent

digestion by the host.

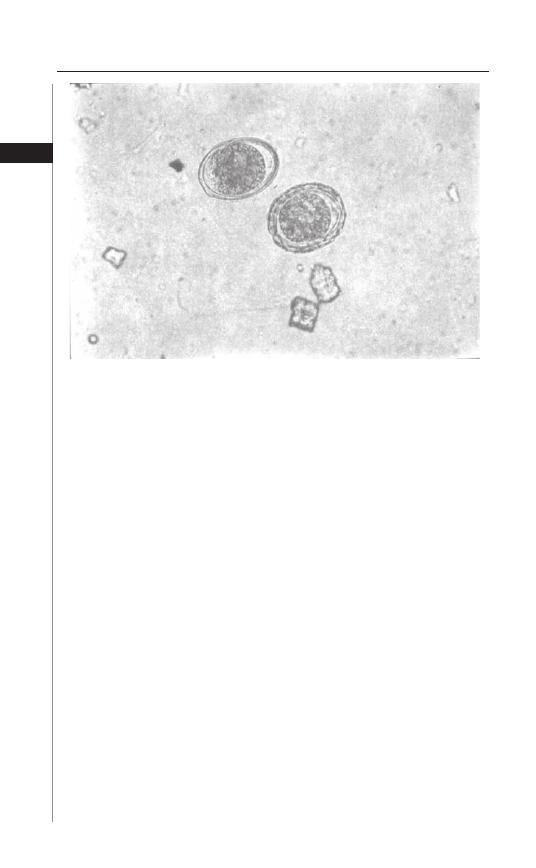

Th e adult female worm can produce 200,000 eggs per day (Fig. 3.2). Th e eggs

that pass out of the adult worm are fertilized, but not embryonated. Once the

eggs exit the host via feces, embryonation occurs in the soil and the embryonated

eggs are subsequently ingested. Th ere is a mucopolysaccharide on the surface that

Figure 3.1. Life Cycle of Ascaris lumbricoides. Reproduced from: Nappi AJ,

Vass E, eds. Parasites of Medical Importance. Austin: Landes Bioscience,

2002:82.

16

Medical Parasitology

3

promotes adhesion of the eggs to environmental surfaces. Within the embryonated

egg, the fi rst stage larva develops into the second stage larva. Th is second stage larva

is stimulated to hatch by the presence of both the alkaline conditions in the small

intestine and the solubilization of its outer layer by bile salts.

Th e hatched parasite that now resides in the lumen of the intestine penetrates

the intestinal wall and is carried to the liver through the portal circulation. It then

travels via the blood stream to the heart and lungs by the pulmonary circulation.

Th e larva molts twice, enlarges and breaks into the alveoli of the lung. Th ey then

pass up through the bronchi and into the trachea, are swallowed and reach the

small intestine once again. Within the small intestine, the parasites molt twice

more and mature into adult worms. Th e adult worms mate, although egg produc-

tion may precede mating.

Clinical Manifestations

Although most individuals infected with Ascaris lumbricoides are essentially

asymptomatic, the burden of symptomatic infection is relatively high as a result

of the high prevalence of infection on a worldwide basis. Symptomatic disease is

usually related to either the larval migration stage and manifests as pulmonary

disease, or to the intestinal stage of the adult worm.

Th e pulmonary manifestations of ascariasis occur during transpulmonary

migration of the organisms and are directly related to the concentration of

larvae. Th us, symptoms are more pronounced with higher burdens of migratory

worms. Th e transpulmonary migration of helminth larvae is responsible for the

development of a transient eosinophilic pneumonitis characteristic of Loeffl er’s

syndrome with peripheral eosinophilia, eosinophilic infi ltrates and elevated se-

rum IgE concentrations. Symptoms usually develop 9-12 days aft er ingestion of

the eggs, while the larvae reside in the lung. Aff ected individuals oft en develop

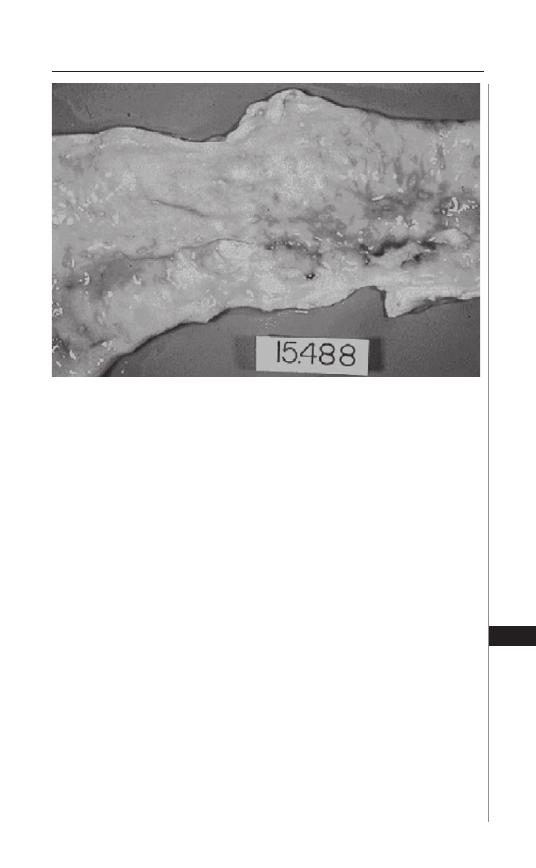

Figure 3.2. Ascaris lumbricoides.

17

Ascariasis

3

bronchospasm, dyspnea and wheezing. Fever, a persistent, nonproductive cough

and, at times chest pain, can also occur. Hepatomegaly may also be present. In

some areas of the world such as Saudi Arabia where transmission of infection is

related to the time of the year, seasonal pneumonitis has been described.

Th e diagnosis of Ascaris-related pneumonitis is suspected in the correct clinical

setting by the presence of infi ltrates on chest X-ray which tend to be migratory and

usually completely clear aft er several weeks. Th e pulmonary infi ltrates are usually

round, several millimeters to centimeters in size, bilateral and diff use.

Among the more serious complications of Ascaris infection is intestinal obstruc-

tion. Th is occurs when a large number of worms are present in the small intestine

and is usually seen in children with heavy worm burdens. Th ese patients present

with nausea, vomiting, colicky abdominal pain and abdominal distention. In this

condition worms may be passed via vomitus or stools. In endemic areas, 5-35%

of all cases of intestinal obstruction can be attributable to ascariasis. Th e adult

worms can also perforate the intestine leading to peritonitis. Ascaris infection can

be complicated by intussusception, appendicitis and appendicular perforation due

to worms entering the appendix.

A potenital consequence of the intestinal phase of the infection relates to the

eff ect it may have on the nutritional health of the host. Children heavily infected

with Ascaris have been shown to exhibit impaired digestion and absorption of

proteins and steatorrhea. Heavy infections have been associated with stunted

growth and a reduction in cognitive function. However, the role of Ascaris in these

defi ciencies is not clearly defi ned. Some of these studies were done in developing

countries where additional nutritional factors cannot be excluded. Th ere is also

a high incidence of co-infection with other parasites that can aff ect growth and

nutritional status. Interestingly, a controlled study done in the southern United

States failed to demonstrate signifi cant diff erences in the nutritional status of

Ascaris infected and uninfected individuals.

Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Symptoms

Hepatobiliary symptoms have been reported in patients with Ascariasis and

are due to the migration of adult worms into the biliary tree. Aff ected individuals

can experience biliary colic, jaundice, ascending cholangitis, acalculous cholecys-

titis and perforation of the bile duct. Pancreatitis may develop as a result of an

obstruction of the pancreatic duct. Hepatic abscesses have also been reported.

Sandouk et al studied 300 patients in Syria who had biliary or pancreatic involve-

ment. Ninety-eight percent of the patients presented with abdominal pain, 16%

developed ascending cholangitis, 4% developed pancreatitis and 1% developed

obstructive jaundice. Both ultrasonography, as well as endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) have been used as diagnostic tools for biliary

or pancreatic ascariasis. In Sandouk’s study extraction of the worms endoscopi-

cally resulted in resolution of symptoms.

Diagnosis

Th e diagnosis of ascariasis is made through microscopic examination of stool

specimens. Ascaris eggs are easily recognized, although if very few eggs are present

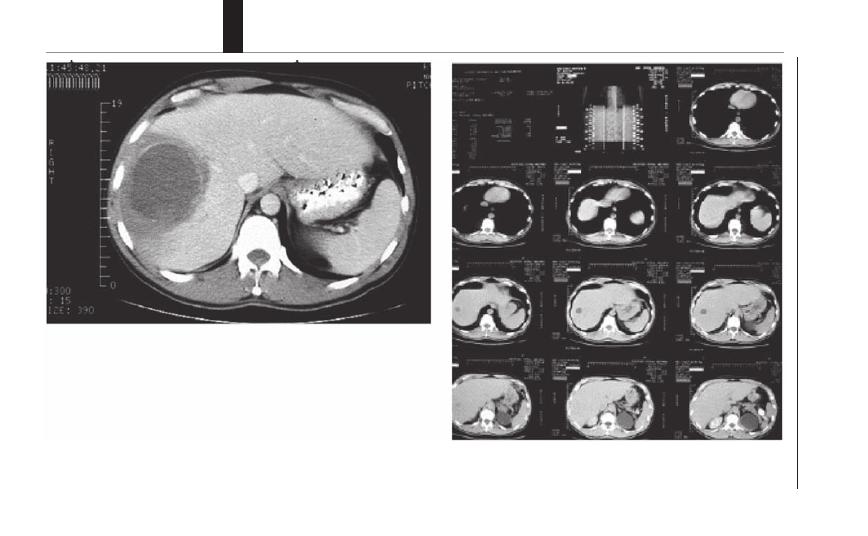

the diagnosis may be easily missed (Fig. 3.3). Techniques for concentrating the stool

18

Medical Parasitology

3

specimen will increase the yield of diagnosis through microscopy. Occasionally an

adult worm is passed via rectum. Eosinophilia may be present, especially during

the larval migration through the lungs. In very heavily infected individuals a plain

X-ray of the abdomen may sometimes reveal a mass of worms.

Treatment

Both albendazole and mebendazole are effective therapies for ascariasis.

Mebendazole can be prescribed as 100 mg BID for 3 days or 500 mg as a single

dose. Th e adverse eff ects of the drug include gastrointestinal symptoms, headache

and rarely leukopenia. Albendazole is prescribed as a single dose of 400 mg.

Albendazole’s side eff ect profi le is similar to mebendazole.

Th e drug piperazine citrate is an alternative therapeutic option, but it is not

widely available and has been withdrawn from the market in some developed

countries as other less toxic and more eff ective therapy is available. However, in

cases of intestinal or biliary obstruction it can be quite useful as it paralyses the

worms, allowing them to be expelled by peristalsis. It is dosed as 50-75 mg/kg QD,

up to a maximum of 3.5 g for 2 days. It can be administered as piperazine syrup

via a naso-gastric tube.

Finally, pyrantel pamoate can be used at a single dose of 11 mg/kg, up to a maxi-

mum dose of 1 g. Th is drug can be used in pregnancy. Th e side eff ects of pyrantel

pamoate include headache, fever, rash and gastrointestinal symptoms. It has been

reported to be up to 90% eff ective in treating the infection.

Th ese medications are all active against the adult worm and are not active against

larval stage. Th us, reevaluation of infected individuals is recommended following

therapy. Family members should also be screened as infection is common among

other members of a household. Treatment does not protect against reinfection.

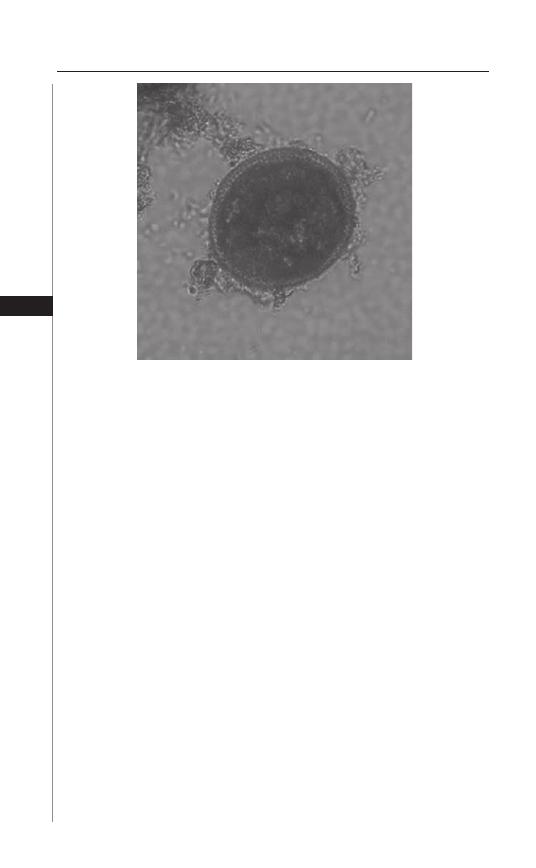

Figure 3.3. Ascaris lumbricoides egg.

19

Ascariasis

3

Prevention

Given the high prevalence of infection with Ascaris lumbricoides and the

potential health and educational benefi ts of treating the infection in children,

the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended global deworming

measures aimed at school children. Th e goal of recent helminth control programs

has been to recommend periodic mass treatment where the prevalence of infection

in school aged children is greater than 50%. Th e current goal is to treat infected

individual 2 to 3 times a year with either mebendazole or albendazole. Integrated

control programs combining medical treatment with improvements in sanitation

and health education are needed for eff ective long-term control.

Suggested Reading

1. Ali M, Khan AN. Sonography of hepatobiliary ascariasis. J Clin Ultrasound 1996;

24:235-41.

2. Anderson TJ. Ascaris infections in human from North America: Molecular

evidence for cross infection. Parasitology 1995; 110:215-29.

3. Bean WJ. Recognition of ascariasis by routine chest or abdomen roentgenograms.

Am J Roentgenol Rad Th er Nucl Med 1965; 94:379.

4. Blumenthal DS, Schultz AG. Incidence of intestinal obstruction in children

infected by Ascaris lumbricoides. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1974; 24:801.

5. Blumenthal DS, Schultz MG. Eff ect of Ascaris infection on nutritional status in

children. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1976; 25:682.

6. Chevarria AP, Schwartzwelder JC et al. Mebendazole, an eff ective broad spectrum

anti-heminthic. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1973; 22:592-5.

7. Crampton DWT, Nesheim MC, Pawlowski ZS, eds. Ascariasis and Its Public

Health Signifi cance. London: Taylor and Francis, 1985.

8. De Silva NR, Guyatt HL, Bundy DA. Morbidity and mortality due to

Ascaris-induced intestinal obstruction. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1997;

91:31-6.

9. DeSilva NR, Chan MS, Bundy DA. Morbidity and mortality due to ascariasis:

Re-estimation and sensitivity analysis of global numbers at risk. Trop Med Int

Health 1997; 2:519-28.

10. Despommier DD, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ et al, eds. Parasitic Diseases, 5th edition.

New York: Apple Tree Productions, 2005:115-20.

11. Gelpi AP, Mustafa A. Seosonal pneumonitis with eosinophilia: A study of larval

ascariasis in Saudi Arabia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1967; 16:646.

12. Jones JE. Parasites in Kentucky: the past seven decades. J KY Med Assoc 1983;

81:621.

13. Khuroo MS. Ascariasis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1996; 25:553-77.

14. Khuroo MS. Hepato-biliary and pancreatic ascariasis. Indian J Gastroenterol 2001;

20:28.

15. Loeffl er W. Transient lung infi ltrations with blood eosinophilia. Int Arch Allergy

Appl Immunol 1956; 8:54.

16. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and Practices of Infectious

Disease, 5th edition. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2000:2941.

17. Norhayati M, Oothuman P, Azizi O et al. Effi cacy of single dose albendazole on the

prevalence and intensity of infection of soil-transmitted helminths in Orang Asli

children in Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1997; 28:563.

18. O’Lorcain, Holland CU. Th e public health importance of Ascaris lumbricoides.

Parasitology 2000; 121:S51-71.

19. Phills JA, Harold AJ, Whiteman GV et al. Pulmonary infi ltrates, asthma, eosino-

philia due to Ascaris suum infestation in man. N Engl J Med 1972; 286:965.

20

Medical Parasitology

3

20. Reeder MM. Th e radiographic and ultrasound evaluation of ascariasis of the

gastrointestinal, biliary and respiratory tract. Semin Roentgenol 1998; 33:57.

21. Sandou F, Haff ar S, Zada M et al. Pancreatic-biliary ascariasis: Experience of 300

cases. Am J Gastroenterol 1997; 92:2264-7.

22. Sinniah B. Daily egg production of Ascaris lumbricoides: Th e distribution of eggs

in the feces and the variability of egg counts. Parasitology 1982; 84:167.

23. Stephenson LS. Th e contribution of Ascaris lumbricoides to malnutrition in

children. Parasitolgy 1980; 81:221-33.

24. Warren KS, Mahmoud AA. Algorithems in the diagnosis and management of

exotic diseases, xxii ascariasis and toxocariaisis. J Infec Dis 1977; 135:868.

25. WHO Health of school children: Treatment of intestinal helminths and schistoso-

miasis (WHO/Schisto/95.112; WHO/CDS/95.1). World Health Organisation

1995.

C

HAPTER

4

Medical Parasitology, edited by Abhay R. Satoskar, Gary L. Simon, Peter J. Hotez

and Moriya Tsuji. ©2009 Landes Bioscience.

Hookworm

David J. Diemert

Introduction

Human hookworm infection is a soil-transmitted helminth infection caused

primarily by the nematode parasites Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duo-

denale. It is one of the most important parasitic infections worldwide, ranking

second only to malaria in terms of its impact on child and maternal health. An

estimated 576 million people are chronically infected with hookworm and an-

other 3.2 billion are at risk, with the largest number of affl icted individuals living

in impoverished rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa, southeast Asia and tropical re-

gions of the Americas. N. americanus is the most widespread hookworm globally,

whereas A. duodenale is more geographically restricted in distribution. Although

hookworm infection does not directly account for substantial mortality, its

greater health impact is in the form of chronic anemia and protein malnutrition

as well as impaired physical and intellectual development in children.

Humans may also be incidentally infected by the zoonotic hookworms

Ancylostoma caninum, Ancylostoma braziliensis and Uncinaria stenocephala,

which can cause self-limited dermatological lesions in the form of cutaneous

larva migrans. Additionally, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, normally a hookworm

infecting cats, has been reported to cause hookworm disease in humans espe-

cially in Asia, whereas A. caninum has been implicated as a cause of eosinophilic

enteritis in Australia.

Life Cycle

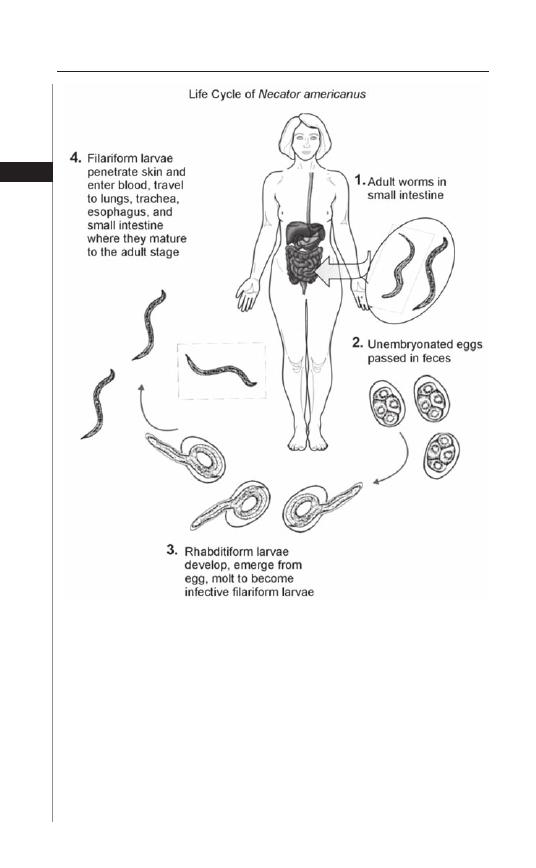

Hookworm transmission occurs when third-stage infective fi lariform larvae

come into contact with skin (Fig. 4.1). Hookworm larvae have the ability to actively

penetrate the cutaneous tissues, most oft en those of the hands, feet, arms and legs

due to exposure and usually through hair follicles or abraded skin. Following skin

penetration, the larvae enter subcutaneous venules and lymphatics to gain access

to the host’s aff erent circulation. Ultimately, they enter the pulmonary capillaries

where they penetrate into the alveolar spaces, ascend the brachial tree to the trachea,

traverse the epiglottis into the pharynx and are swallowed into the gastrointestinal

tract. Larvae undergo two molts in the lumen of the intestine before developing into

egg-laying adults approximately fi ve to nine weeks aft er skin penetration. Although

generally one centimeter in length, adult worms exhibit considerable variation in

size and female worms are usually larger than males (Fig. 4.2).

Adult Necator and Ancylostoma hookworms parasitize the proximal portion of

the human small intestine where they can live for several years, although diff erences

22

Medical Parasitology

4

exist between the life spans of the two species: A. duodenale survive for on average

one year in the human intestine whereas N. americanus generally live for three to

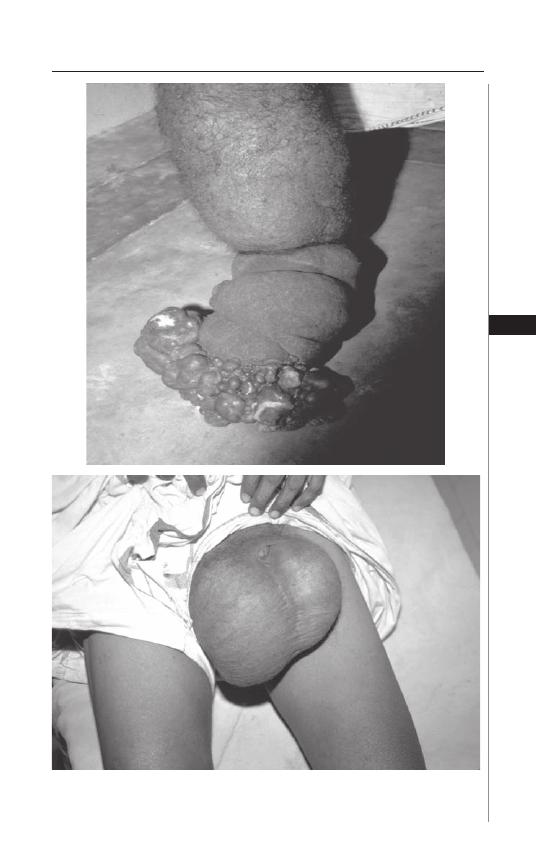

fi ve years (Fig. 4.3). Adult hookworms attach onto the mucosa of the small intestine

by means of cutting teeth in the case of A. duodenale or a rounded cutting plate in

the case of N. americanus. Aft er attachment, digestive enzymes are secreted that

enable the parasite to burrow into the tissues of the submucosa where they derive

nourishment from eating villous tissue and sucking blood into their digestive tracts.

Hemoglobinases within the hookworm digestive canal enable digestion of human

hemoglobin, which is a primary nutrient source of the parasite.

Figure 4.1. Life cycle of the hookworm, Necator americanus. Reproduced

from: Nappi AJ, Vass E, eds. Parasites of Medical Importance. Austin: Landes

Bioscience, 2002:80.

23

Hookworm

4

Humans are considered the only major defi nitive host for these two parasites and

there are no intermediate or reservoir hosts; in addition, hookworms do not reproduce

within the host. Aft er mating in the host intestinal tract, each female adult worm

produces thousands of eggs per day which then exit the body in feces. A. duodenale

female worms lay approximately 28,000 eggs daily, while the output from N. ameri-

canus worms is considerably less, averaging around 10,000 a day. N. americanus and

A. duodenale hookworm eggs hatch in warm, moist soil, giving rise to rhabditiform

larvae that grow and develop, feeding on organic material and bacteria. Aft er about

seven days, the larvae cease feeding and molt twice to become infective third-stage

fi lariform larvae. Th ird-stage larvae are nonfeeding but motile organisms that seek out

higher ground such as the tips of grass blades to increase the chance of contact with

human skin and thereby complete the life cycle. Filariform larvae can survive for up

to approximately two weeks if an appropriate host is not encountered.

A. duodenale larvae can also be orally infective and have been conjectured to

infect infants during breast feeding.

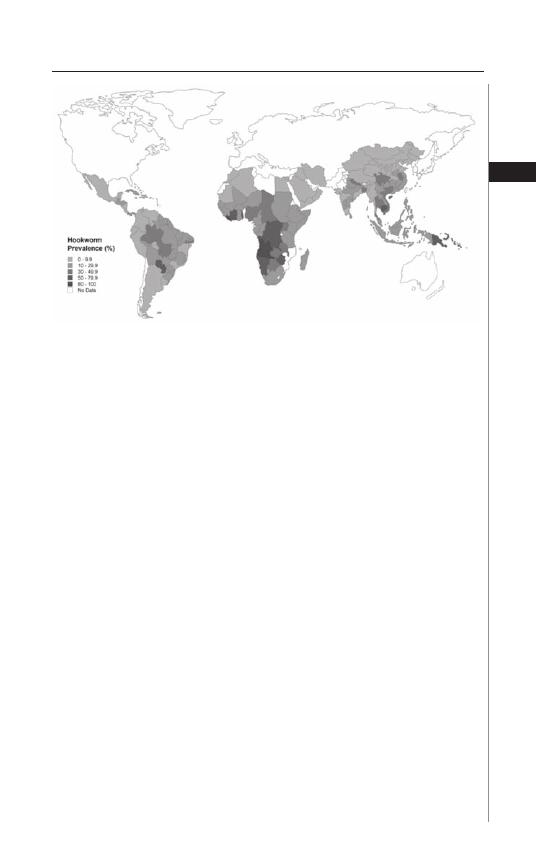

Epidemiology and Burden of Disease

Human hookworm infections are widely distributed throughout the trop-

ics and sub-tropics (Fig. 4.4). N. americanus is the most prevalent hookworm

worldwide, with the highest rates of infection in sub-Saharan Africa, the tropical

Figure 4.2. Adult male Ancylostoma duodenale hookworm. Reproduced

with permission from: Despommier DD, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ, Knirsch CA.

Parasitic Diseases. New York: Apple Trees Productions, 2005:121.

24

Medical Parasitology

4

regions of the Americas, south China and southeast Asia, whereas A. duodenale

is more focally endemic in parts of India, China, sub-Saharan Africa, North

Africa and a few regions of the Americas. Climate is an important determinant

of hookworm transmission, with adequate moisture and warm temperature

essential for larval development in the soil. An equally important determinant

of infection is poverty and the associated lack of sanitation and supply of clean

water. In such conditions, other helminth species are frequently co-endemic,

with emerging evidence that individuals infected with multiple diff erent types

of helminths (most commonly the triad of Ascaris lumbricoides, hookworm

and Trichuris trichiura) are predisposed to developing even heavier intensity

infections than those who harbor single-species infections. Because morbidity

from hookworm infections and the rate of transmission are directly related to

the number of worms harbored within the host, the intensity of infection is the

primary epidemiological parameter used to describe hookworm infection as

measured by the number of eggs per gram of feces.

While prevalence in endemic areas increases markedly with age in young chil-

dren and reaches a plateau by around an age of ten years, intensity of infection

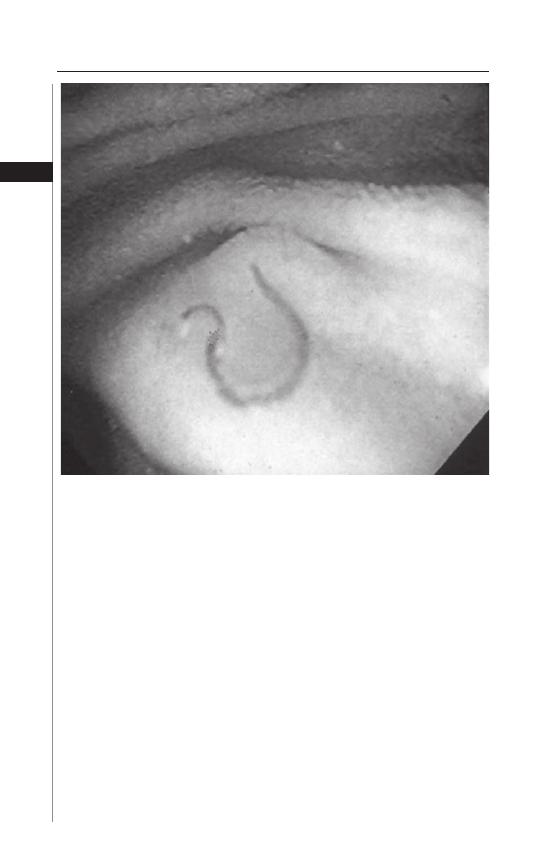

Figure 4.3. Adult hookworm, diagnosed by endoscopy. Reproduced with per-

mission from: Despommier DD, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ, Knirsch CA. Parasitic

Diseases. New York: Apple Trees Productions, 2005:123.

25

Hookworm

4

rises at a slower rate during childhood, reaching a plateau by around 20 years and

then increasing again from age 60 years onward. Controversy persists whether

such age-dependency refl ects changes in exposure, acquired immunity, or a com-

bination of both. Although heavy hookworm infections also occur in childhood,

it is common for prevalence and intensity to remain high into adulthood, even

among the elderly. Hookworm infections are oft en referred to as “overdispersed” in

endemic communities, such that the majority of worms are harbored by a minority

of individuals in an endemic area. Th ere is also evidence of familial and household

aggregation of hookworm infection, although the relative importance of genetics

over the shared household environment is debated.

Although diffi cult to ascertain, it is estimated that worldwide approximately

65,000 deaths occur annually due to hookworm infection. However, hookworm

causes far more disability than death. Th e global burden of hookworm infec-

tions is typically assessed by estimating the number of Disability Adjusted Life

Years (DALYs) lost. According to the World Health Organization, hookworm

accounts for the loss of 22 million DALYs annually, which is almost two-thirds

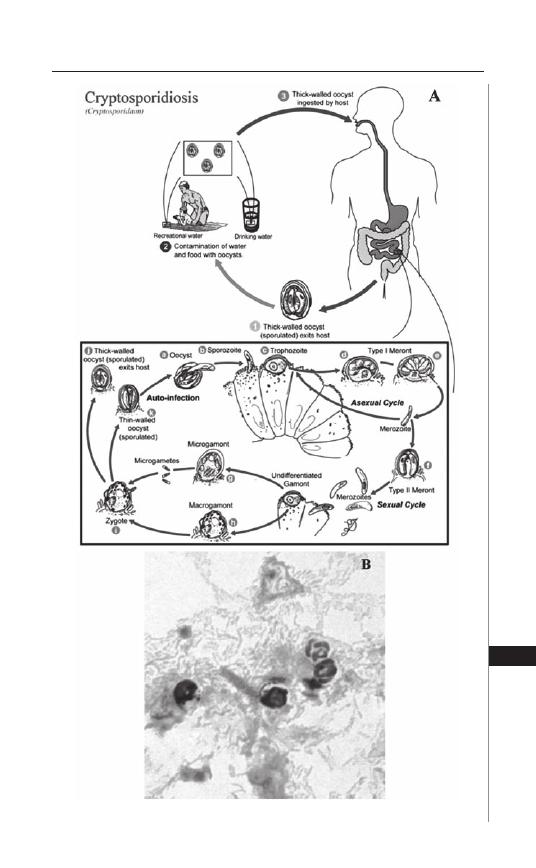

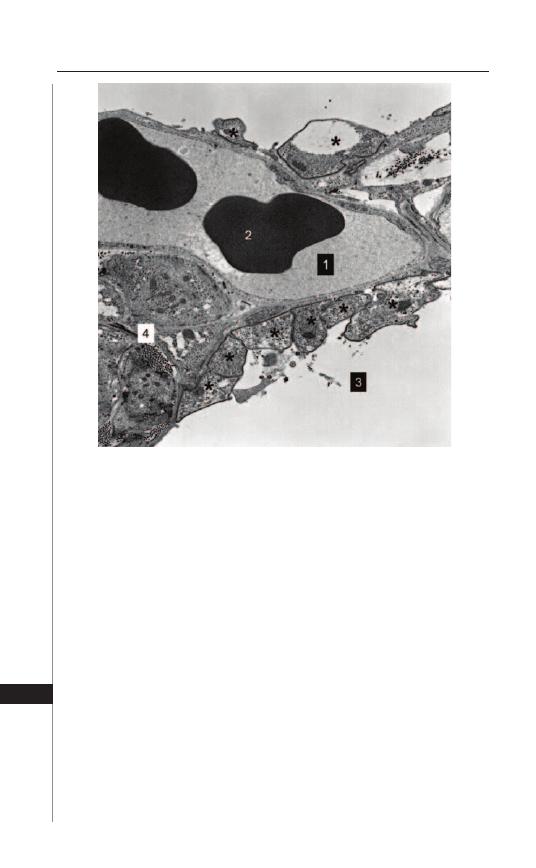

that of malaria or measles. Th is estimate refl ects the long-term consequences of