GLOMERULAR DISEASES

Lecture 1Glomerular disease includes:

glomerulonephritis: inflammation of the glomeruli glomerulopathies: there is no evidence of inflammation.

There is an overlap between these terms.

Types of glomerular disease

The terms used to describe histologically the number of glomeruli affected in a given condition:

diffuse: majority of glomeruli abnormal (>50%)

focal: some glomeruli affected

Terms used to describe histologically the extent to which individual glomeruli are affected in a given condition:

global: entire glomerulus abnormal

segmental: only part of the glomerulus abnormal

Types of Changes

proliferation: hyperplasia of one of the glomerular cell types (mesangial, endothelial, parietal epithelial), with or without inflammatory cell infiltration

membranous changes: capillary wall thickening due to immune deposits or alterations in basement membrane

crescent formation: parietal epithelial cell proliferation and mononuclear cell infiltration form crescent-shape in Bowman’s space.

Histological Terms of Glomerular Changes

Glomerular diseases account for a significant proportion of acute and chronic kidney disease.

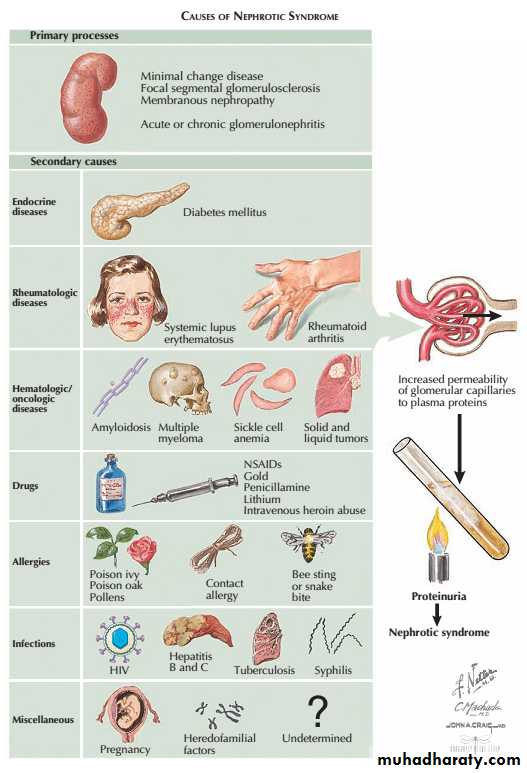

There are many causes of glomerular damage, including

immunological injury,

inherited diseases such as Alport’s syndrome

metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and

deposition of abnormal proteins such as amyloid in the glomeruli.

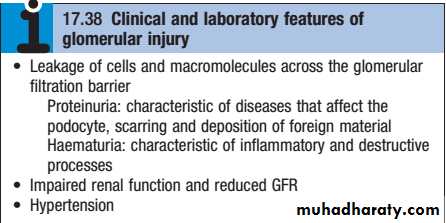

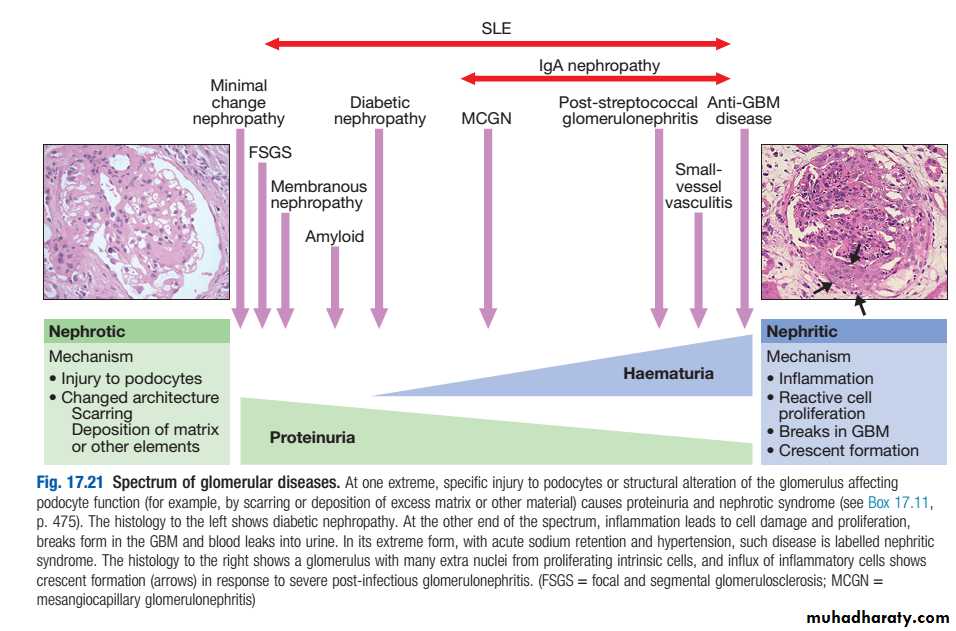

The response of the glomerulus to injury and hence the predominant clinical features vary according to the nature of the insult .

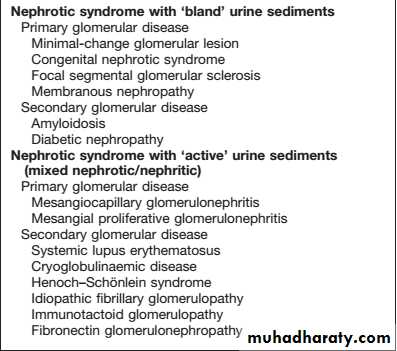

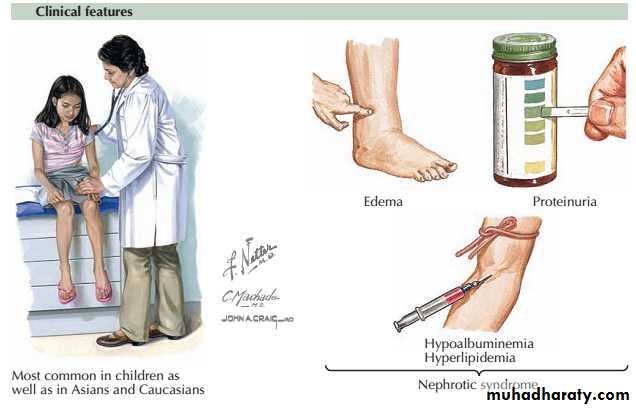

Nephrotic syndrome : massive proteinuria (>3.5g/day),hypoalbuminaemia, oedema, lipiduria andhyperlipidaemia.

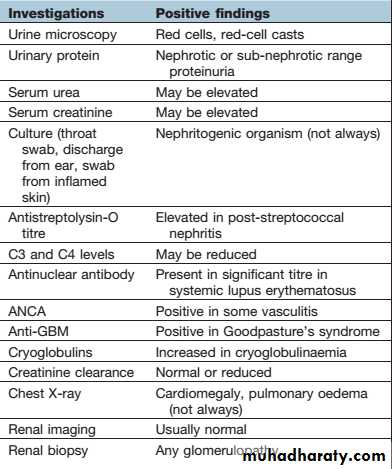

Acute glomerulonephritis (acute nephritic syndrome):abrupt onset of glomerular haematuria (RBCcasts ordysmorphic RBC),non-nephrotic range proteinuria,oedema,hypertension and transient renal impairment.

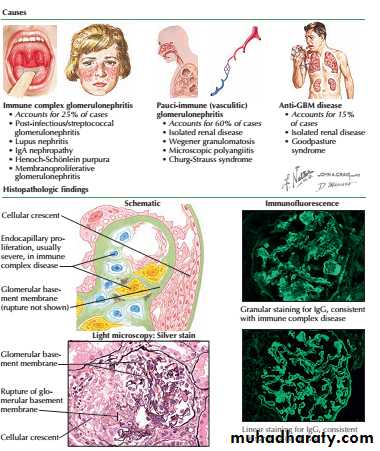

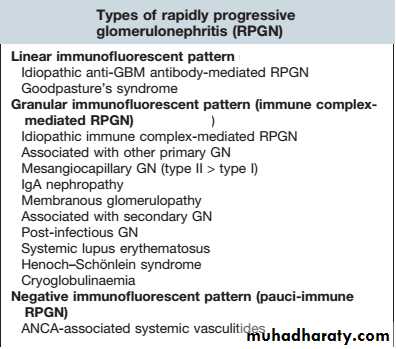

Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis:features of acute nephritis, focal necrosis with or without crescents and rapidly progressive renal failure over weeks.

Asymptomatic haematuria, proteinuria or both.

Certain types of GN,particularly those that are a part of systemic disease,can present as more than one syndrome, e.g. lupus nephritis,cryoglobulinaemia, and Henoch– Schönlein purpura.

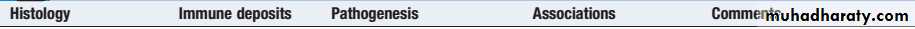

Classification of glomerulopathies

Investigation of glomerular diseases

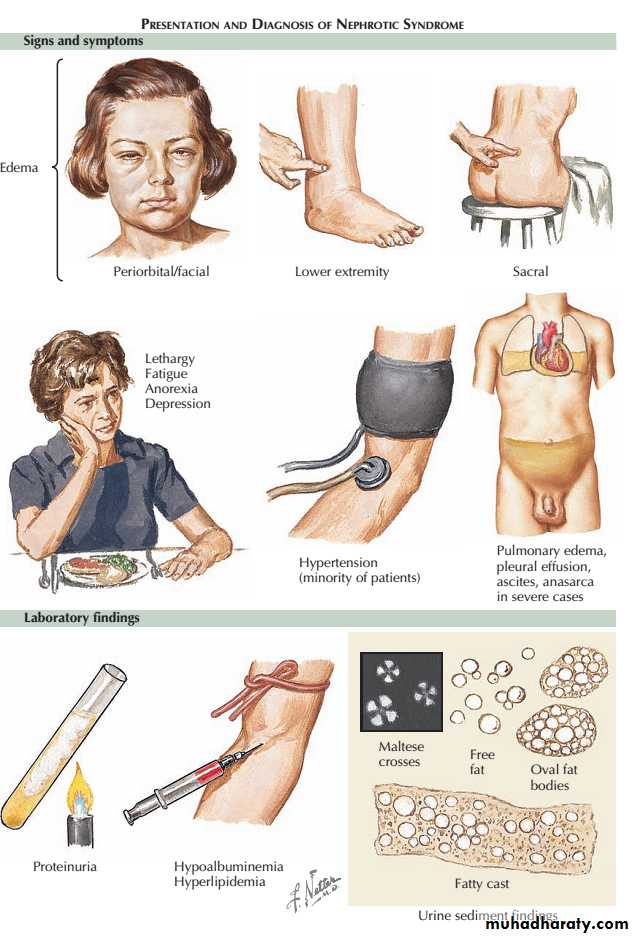

The nephrotic syndrome encompasses a constellation of clinical and laboratory findings related to the loss of large quantities of protein in urine.

The major symptom is edema, and the laboratory findings include

(1) “nephrotic-range” proteinuria, defined in adults as more than 3.5 g of protein excretion per 24 hours,

(2) hypoalbuminemia,

(3) Lipiduria and hyperlipidemia.

The threshold for nephrotic proteinuria in children is lower and depends on body weight.

NEPHROTIC SYNDROME

Proteinuria :The mechanism of the proteinuria is complex.It occurs partly because structural damage to the glomerular basement membrane leads to an increase in the size and number of pores, allowing passage of more and larger molecules.

Electrical charge is also involved in glomerular permeability. Fixed negatively charged component are present in the glomerular capillary wall, which repel negatively charged protein molecules. Reduction of this fixed charge occurs in glomerular disease and appears to be a key factor in the genesis of heavy proteinuria.

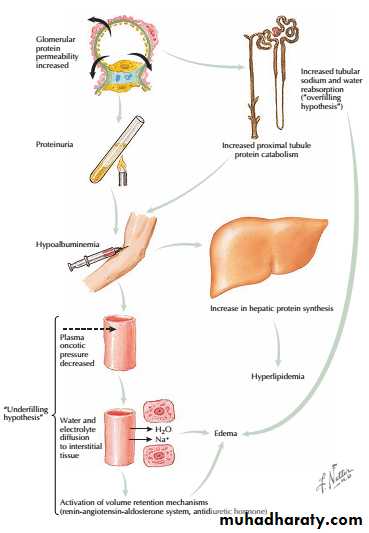

Pathophysiology

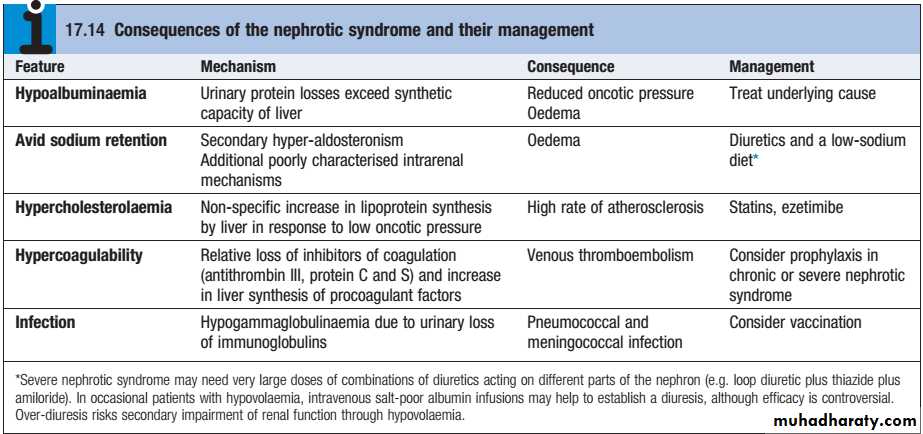

Hypoalbuminaemia:Urinary protein loss 3.5g daily or more in an adult is required to cause hypoalbuminaemia due to the ongoing loss of albumin into urine. The decline in serum albumin concentration, however, is often out of proportion to the degree of proteinuria. One possible explanation is that the proximal tubular catabolism of albumin is accelerated because of the increased filtered load.

• Hyperlipidaemia :In response to the low serum albumin concentrations, the liver increases its production of numerous proteins, including lipoproteins, leading to hyperlipidemia.

• Edema : occurs for at least two possible reasons.

• The first, known as the “underfilling hypothesis,” argues that low serum albumin concentrations lead to a reduction in intravascular oncotic pressure. As a result, plasma moves from the capillary lumen to the interstitium, which leads to edema. The resulting intravascular depletion activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which promotes retention of sodium and water and thus further worsens the edema.

The second hypothesis, known as the “overfilling hypothesis,” argues that there is primary retention of sodium at the level of the collecting duct, perhaps triggered by the filtered proteins themselves, that leads to edema. It appears probable that both hypotheses are correct, and that the primary mechanism for edema may vary across patients and across time.

Initial treatment should be with dietary sodium restriction and a thiazide diuretic (e.g.bendroflumethiazide 5 mg daily) . Unresponsive patients require furosemide 40–120mg daily with the addition of amiloride (5 mg daily), with the serum potassium concentration monitored regularly.

Nephrotic patients may malabsorb diuretics (as well as other drugs) owing to gut mucosal oedema, and parenteral administration is then required initially.

Management1)General measures

Normal or low protein intake is advisable.A high-protein diet

(80–90 g protein daily) increases proteinuria and can be Harmful in the long term.

Albumin infusion :produces only a transient effect.It is only given to patients who are diuretic-resistant and those with oliguria and uraemia in the absence of severe glomerular damage, e.g. in minimal-change nephropathy. Albumin infusion is combined with diuretic

therapy and diuresis often continues with diuretic treatment alone.

ACE inhibitors and/or angiotensin II receptor

antagonistsare used for their antiproteinuricproperties in all types of GN.

These groups of drugs reduce proteinuria by lowering glomerular capillary filtration pressure; the blood pressure and renal function should be monitored regularly.

Management of proteinuria should be directed at the underlying cause. This may involve immunosuppressive therapy in glomerulonephritis.

2)Specific measures

GLOMERULAR DISEASES

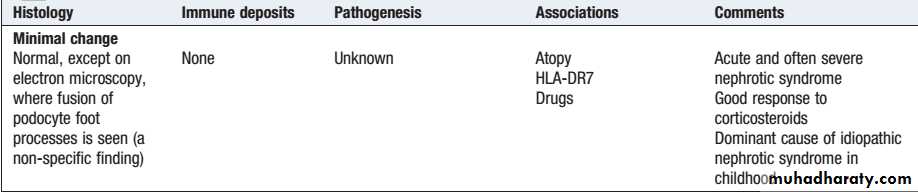

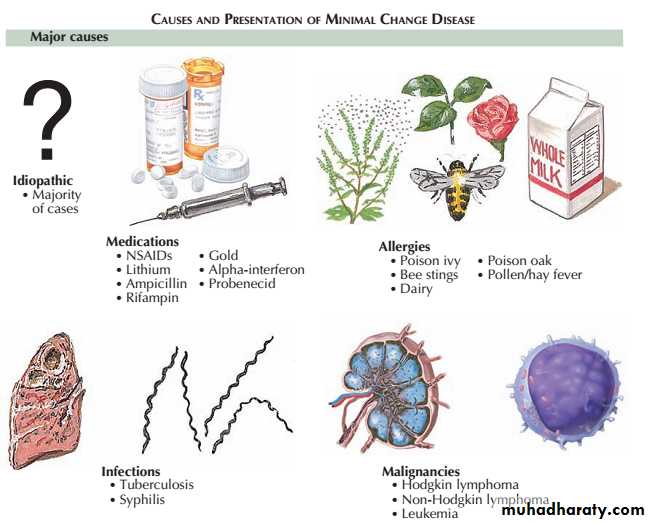

Lecture 2Minimal change disease occurs at all ages but accounts for nephrotic syndrome in most children and about onequarter of adults. It is caused by reversible dysfunction of podocytes.

The presentation is with proteinuria or nephrotic syndrome, which typically remits with highdose corticosteroid therapy (1 mg/kg prednisolone for 6 weeks).

Minimal change disease does not progress to CKD but can present with problems related to the nephrotic syndrome and complications of treatment.

Minimal-change glomerular lesion (minimal-change nephropathy, minimal-change disease, MCD

The primary, idiopathic form of MCD is very responsive to steroids. Up to 95% of patients achieve complete remission, defined as proteinuria declining to levels below 300 mg/day with stable renal function.

Some patients who respond incompletely or relapse frequently need maintenance corticosteroids, cytotoxic therapy or other agents.

Secondary forms of MCD should be treated by focusing on removal or mitigation of the inciting insult, such as discontinuation of a certain drug or treatment of an underlying malignancy.

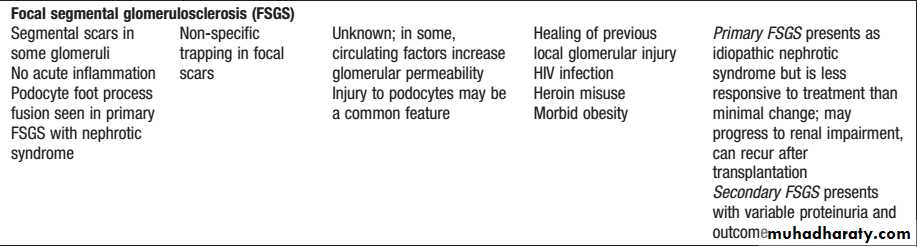

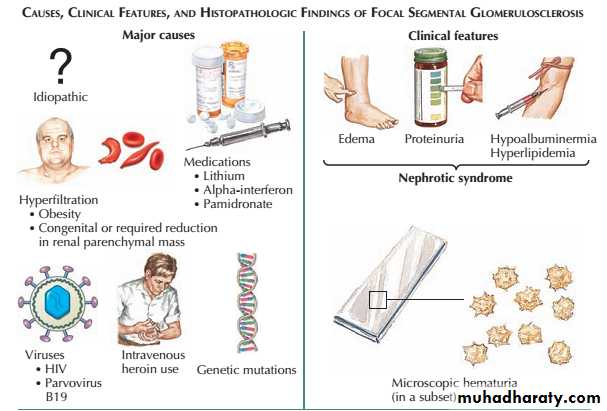

Primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) can occur in all age groups. In some patients, FSGS can have specific causes, such as HIV infection, podocyte toxins and massive obesity, but in most cases the underlying cause is unknown (primary FSGS).

Patients with primary FSGS present with massive proteinuria and idiopathic nephrotic syndrome.

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

Histological analysis shows sclerosis affecting segments of the glomeruli, which may also show non specific traping staining deposits of C3 and IgM on immunofluorescence.

Since FSGS is a focal process, abnormal glomeruli may not be seen on renal biopsy if only a few are sampled, leading to an initial diagnosis of minimal change nephropathy.

Juxtamedullary glomeruli are more likely to be affected in early disease.

Although nephrotic syndrome is typical, some patients present with the histological features of FSGS but less proteinuria.

In these patients, the focal scarring may reflect healing of previous focal glomerular injury, such as HUS, cholesterol embolism or vasculitis. These examples of secondary FSGS have different course and treatments.

Primary FSGS can respond to highdose corticosteroid therapy (0.5–2.0 mg/kg/day) but most patients show little or no response.

Immunosuppressive drugs, such as ciclosporin, cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate mofetil, have also been used .

Progression to CKD is common in patients who do not respond to steroids and the disease frequently recurs after renal transplantation, with an almost immediate return of proteinuria following transplant in some cases.

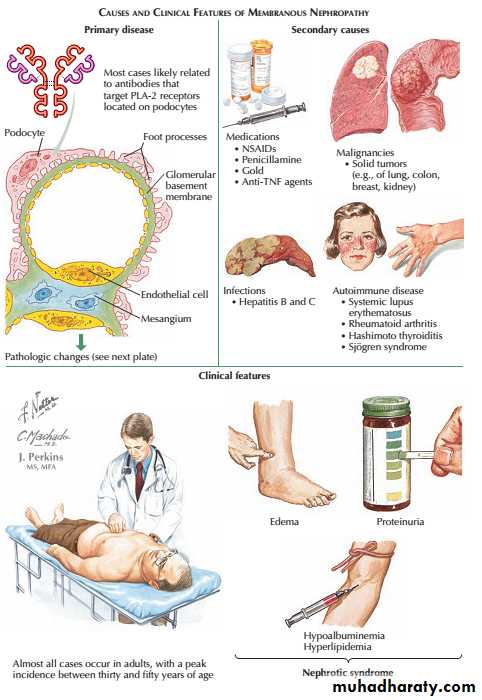

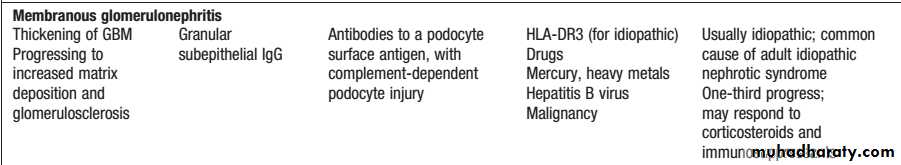

membranous nephropathy, is the most common cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults. It is caused by antibodies (usually autoantibodies) directed at antigen(s) expressed on the surface of podocytes.

Recent studies suggest that one such antigen is the Mtype phospholipase A2receptor1 (antiPLAR2 Abs).

A proportion of cases are associated with other causes, such as heavy metal poisoning, drugs, infections and tumours and but most are idiopathic.

Approximately onethird of patients with idiopathic membranous glomerulonephritis undergo spontaneous remission; onethird remain in a nephrotic state, and onethird go on to develop CKD.

Membranous glomerulopathy

Shortterm treatment with high doses of corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide may improve both the nephrotic syndrome and the longterm prognosis. However, because of the toxicity of these regimens, many nephrologists reserve such treatment for those with severe nephrotic syndrome or deteriorating renal function.

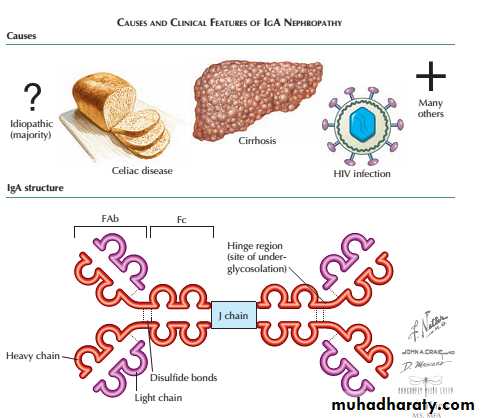

This is one of the most common types of glomerulonephritis and can present in many ways . Haematuria is the earliest sign and is almost universal, and hypertension is also very common.

Proteinuria can also occur but is usually a later feature. In many cases, there is slowly progressive loss of renal function leading to ESRD. Clinical presentations are protean and vary with age.

A particular hallmark of IgA nephropathy in young adults is the occurrence of acute selflimiting exacerbations, often with gross haematuria, in association with minor respiratory infections.

IgA nephropathy

This may be so acute as to resemble acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis, with fluid retention, hypertension and oliguria with dark or red urine.

Characteristically, the latency from clinical infection to nephritis is short: a few days or less.

Asymptomatic presentations dominate in older adults, with haematuria, hypertension and loss of GFR. Occasionally, IgA nephropathy progresses rapidly and crescent formation may be seen.

The prognosis is usually good, especially in those with normal blood pressure,normal renal function and absence of proteinuria at presentation.Surprisingly, recurrent macroscopic haematuria is a good prognostic sign.

The management of less acute disease is largely directed towards the control of blood pressure in an attempt to prevent or retard progressive renal disease.

There is some evidence for additional benefit from several months of highdose corticosteroid treatment in highrisk disease, but no strong evidence for other immunosuppressive agents.

All patients with or without hypertension and proteinuria, should receive ACE inhibitor and/or angiotensin II receptor antagonist which enhances reduction of proteinuria and preservation of renal function.

Thank you

GLOMERULAR DISEASESLecture 3

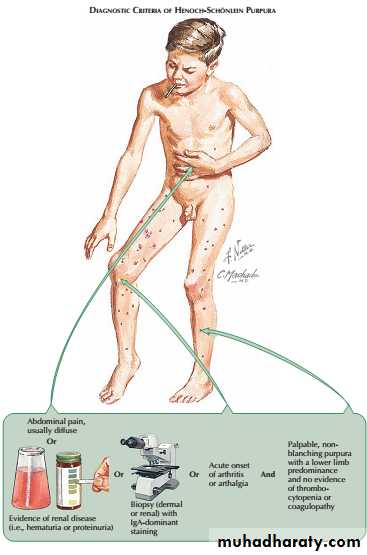

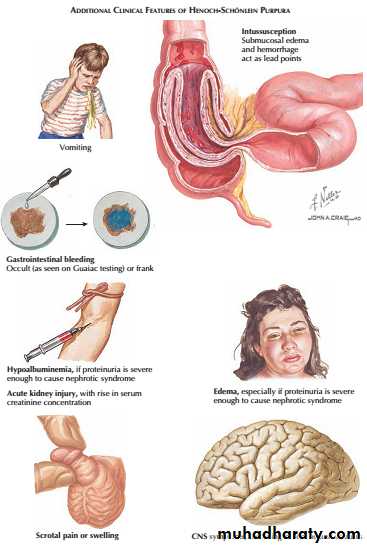

This condition most commonly occurs in children but can also be observed in adults. It is characterised by a systemic vasculitis that often arises in response to an infectious trigger.

The presentation is with a characteristic petechial rash typically affecting buttocks and lower legs, and abdominal pain due to the occurrence of vasculitis involving the gastrointestinal tract.

Henoch–Schönlein purpura

The gastrointestinal disease, which occurs secondary to submucosal edema and hemorrhage, may be limited to pain and vomiting. Some patients, however, may experience more significant complications, such as frank gastrointestinal hemorrhage or intussusception.Less common systemic manifestations include scrotal pain or swelling, as well as central nervous system disease (i.e., headache, seizures).

The presence of glomerulonephritis is usually indicated by the occurrence of haematuria. When Henoch–Schönlein purpura occurs in older children or adults, the glomerulonephritis is usually more prominent and less likely to resolve completely. Renal biopsy shows mesangial IgA deposition and appearances that are indistinguishable from acute IgA nephropathy.

Treatment is supportive in nature; in most patients, the prognosis is good, with spontaneous resolution,

but some, particularly adults, progress to develop ESRD.

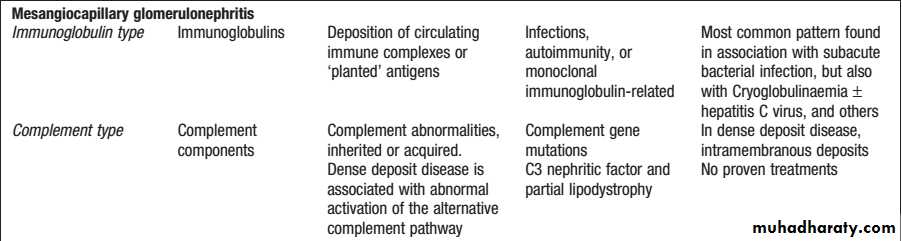

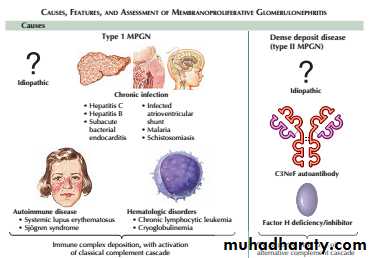

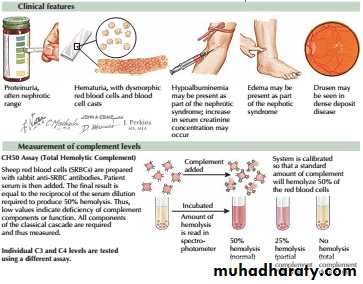

MPGN is characterised by an increase in mesangial cellularity with thickening of glomerular capillary walls and subendothelial deposition of immune complexes and/or components of the complement pathway.

The typical presentation is with proteinuria and haematuria.

Mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (MCGN)”membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis” (MPGN)

It can be classified into two main subtypes.

The first is characterised by deposition of immunoglobulins within the glomeruli. This subtype is associated with chronic infections, autoimmune diseases and monoclonal gammopathy.

The second is characterised by deposition of complement in the glomeruli and is associated with inherited or acquired abnormalities in the complement pathway. Within this category is socalled ‘dense deposit disease’”DDD”, which is typified by deposition of electrondense deposits within the GBM.

The third subtype is recognised, in which neither immunoglobulins nor complement are deposited in the glomeruli. This is associated with healing following thrombotic microangiopathies, such as HUS and TTP.

Treatment of MPGN associated with immunoglobulin deposits consists of identifying and treating the underlying disease, if possible, and the use of immunosuppressive drugs such as mycophenolate mofetil or cyclophosphamide.

There is no specific treatment for MPGN associated with deposition of complement in the glomeruli or for dense deposit disease.

Glomerulonephritis may occur in connection with infections of various types, including subacute bacterial endocarditis.

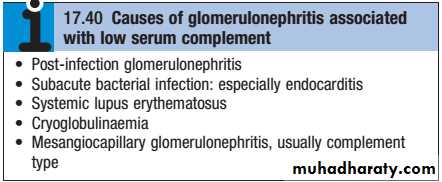

The most common histological pattern in bacterial infection is mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis, often associated with extensive immunoglobulin deposition in the glomeruli with evidence of complement consumption (low serum C3).In the developed world, hospitalacquired infections with various organisms are a common cause of these syndromes.

Worldwide, glomerulonephritis more commonly follows hepatitis B, hepatitis C, schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, malaria and other chronic infections. Infection with HIV may be associated with FSGS , particularly in people of African descent.

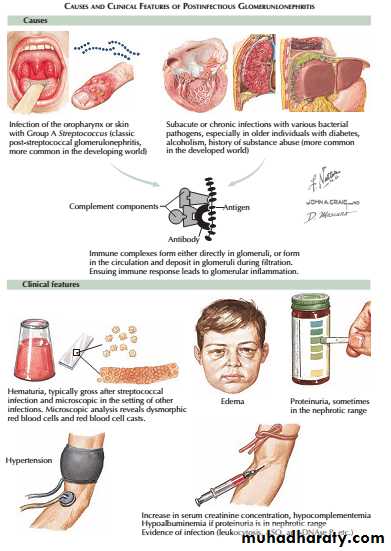

Infection-related glomerulonephritis

This is a specific subtype of postinfectious glomerulonephritis. It is much more common in children than adults .

The latency is usually about 10 days after a throat infection or longer after skin infection, suggesting an immune mechanism rather than direct infection.

An acute nephritis of varying severity occurs. Sodium retention, hypertension and oedema are particularly pronounced. There is also reduction of GFR, proteinuria, haematuria and reduced urine volume. Characteristically, this gives the urine a red or smoky appearance.

postinfectious glomerulonephritis Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis

Serum concentrations of C3 and C4 are typically reduced, reflecting complement consumption , and evidence of streptococcal infection (High “antistreptolysin O “ASO titer) may be found.

Renal function begins to improve spontaneously within 10–14 days, and management by fluid and sodium restriction with diuretic and antihypertensive agents is usually adequate.

Remarkably, the renal lesion in almost all children and many adults seems to resolve completely, despite the severity of the glomerular inflammation and proliferation seen histologically.

Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (also known as crescentic glomerulonephritis) is characterised by rapid loss of renal function over days to weeks.

Renal biopsy shows crescentic lesions, often associated with necrotising lesions within the glomerulus, termed focal segmental (necrotising) glomerulonephritis. It is typically seen in Goodpasture’s disease, where the underlying cause is the development of antibodies to the glomerular basement membrane (antiGBM antibodies), and in smallvessel vasculitides .

It can also be observed in SLE and occasionally IgA and other nephropathies. Rapid onset disease may be associated with relatively little proteinuria .

Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis

Management depends on the underlying cause but immunosuppressive drugs are often required. Patients with antiGBM disease should be treated with plasma exchange combined with corticosteroids and immunosuppressants (cyclophosphamide).

Patients with renal involvement secondary to ANCAassociated vasculitis and SLE should also be treated with corticosteroids and immunosuppressants.

Plasma exchange :to remove circulating antibodies

Steroids: to suppress inflammation from antibody already deposited in the tissue.

Cyclophosphamide: to suppress further antibody synthesis

Thank you

GLOMERULAR DISEASESLecture 4

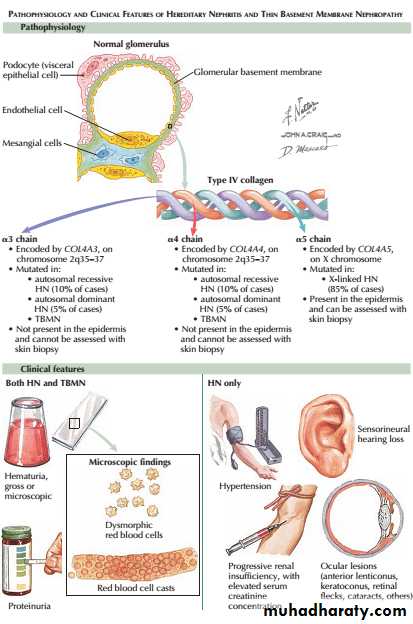

Most cases arise from a mutation or deletion of the COL4A5gene on the X chromosome, which encodes type IV collagen, resulting in inheritance as an Xlinked recessive disorder . Mutations in COL4A3 or COL4A4 genes are less common and cause autosomal recessive disease. The accumulation of abnormal collagen results in a progressive degeneration of the GBM .

A number of uncommon diseases may involve the glomerulus in childhood, but the most important one affecting adults is Alport’s syndrome.

AIport’s syndrome

Affected patients progress from haematuria to ESRD in their late teens or twenties.

Female carriers of COL4A5mutations usually have haematuria but less commonly develop significant renal disease.Some other basement membranes containing the same collagen isoforms are similarly involved, notably in the cochlea, so that Alport’s syndrome is associated with sensorineural deafness and ocular abnormalities(anterior lenticonus and maculopathy).

ACE inhibitors may slow but not prevent loss of kidney function. Patients with Alport’s syndrome are good candidates for RRT, as they are young and usually otherwise healthy.

They can develop an immune response to the normal collagen antigens present in the GBM of the donor kidney and, in a small minority, antiGBM disease develops and destroys the allograft.

In thin glomerular basement membrane disease there is glomerular bleeding, usually only at the microscopic or dipstick level, without associated hypertension, proteinuria or a reduction in GFR. The glomeruli appear normal by light microscopy but, on electron microscopy, the GBM is abnormally thin.

The condition may be familial and some patients are carriers of Alport mutations. This does not appear to account for all cases, and in many patients the cause is unclear. Monitoring of these patients is advisable, as proteinuria may develop in some and there seems to be an increased rate of progressive CKD in the long term.

Thin glomerular basement membrane disease

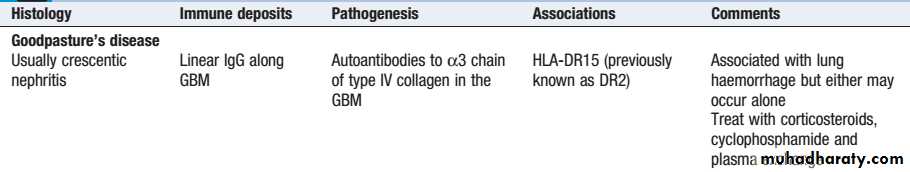

It characterise by antibodies against alpha 3 type IV collagen present in lungs and GBM

more common in 3rd and 6th decades of life, men slightly more affected than females

present with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN) and hemoptysis/dyspnea

pulmonary hemorrhage more common in smokers and males

treat with plasma exchange, cyclophosphamide, steroid

Goodpasture’s diseaseAnti-GBM disease

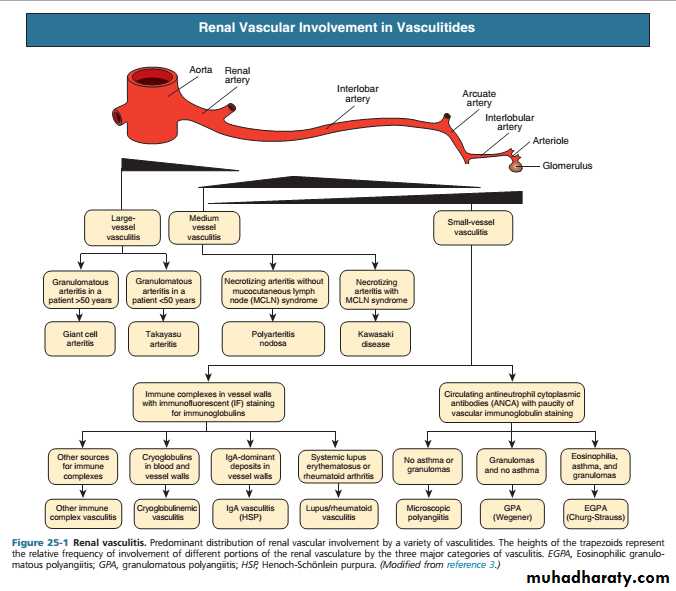

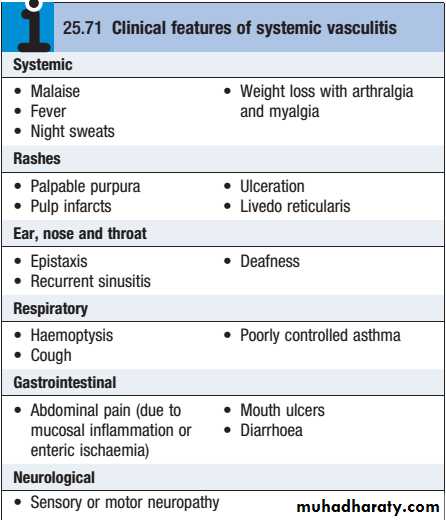

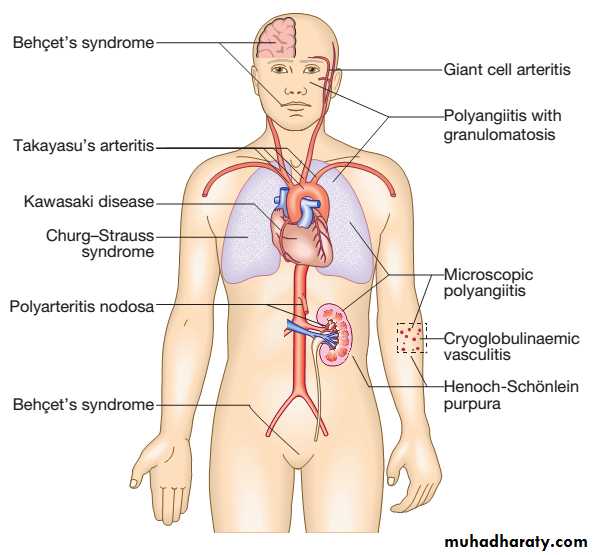

These are a heterogeneous group of diseases characterised by inflammation and necrosis of bloodvessel walls, with associated damage to skin, kidney, lung, heart, brain and gastrointestinal tract.

There is a wide spectrum of involvement and disease severity, ranging from mild and transient disease affecting only the skin, to lifethreatening fulminant disease with multiple organ failure.

Renal and Systemic Vasculitis

The clinical features result from a combination of local tissue ischaemia (due to vessel inflammation and narrowing) and the systemic effects of widespread inflammation. Systemic vasculitis should be considered in any patient with fever, weight loss, fatigue, evidence of multisystem involvement, rashes, raised inflammatory markers and abnormal urinalysis

Classification of vasculitis

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)associated vasculitis is a lifethreatening disorder characterised by inflammatory infiltration of small blood vessels, fibrinoid necrosis and the presence of circulating antibodies to ANCA.

The combined incidence is about 10–15/1 000 000. Two subtypes are recognised.

1)Microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) is a necrotising smallvessel vasculitis found with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, often in association with alveolar haemorrhage. Cutaneous and gastrointestinal involvement is common and other features include neuropathy (15%) and pleural effusions (15%). Patients are usually myeloperoxidase (MPO) antibodypositive.

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis

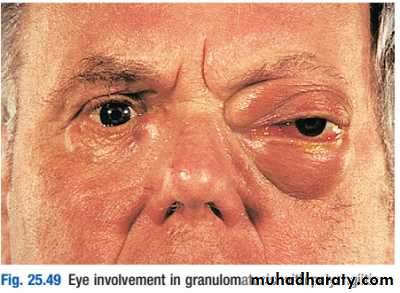

2) granulomatosis with polyangiitis (also known as Wegener’s granulomatosis (WG)), the vasculitis is characterised by granuloma formation, mainly affecting the nasal passages, airways and kidney. A minority of patients present with glomerulonephritis.

The most common presentation of WG is with epistaxis, nasal crusting and sinusitis, but haemoptysis and mucosal ulceration may also occur.

Deafness may be a feature due to inner ear involvement, and proptosis may occur because of inflammation of the retroorbital tissue . This causes diplopia due to entrapment of the extraocular muscles, or loss of vision due to optic nerve compression. Disturbance of colour vision is an early feature of optic nerve compression. Untreated nasal disease ultimately leads to destruction of bone and cartilage.

Migratory pulmonary infiltrates and nodules occur in 50% of patients. Patients with WG are usually proteinase3 (PR3) antibodypositive(c-ANCA).

Patients with active disease usually have a leucocytosis with an elevated CRP and ESR, in association with raised c-ANCA levels.

Complement levels are usually normal or slightly elevated.

Imaging of the upper airways or chest with MRI can be useful in localising abnormalities but, where possible, the diagnosis should be confirmed by biopsy of the kidney or lesions in the sinuses and upper airways

Management is with highdose steroids and cyclophosphamide, followed by maintenance therapy with lowerdose steroids and azathioprine, methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). Rituximab in combination with highdose steroids is equally effective as oral cyclophosphamide at inducing remission in ANCAassociated vasculitis.

Both MPA and WG have a tendency to relapse, and patients must be followed on a regular and longterm basis to check for clinical signs of recurrence.

Measurements of ESR, CRP and levels of ANCA antibodies are useful in monitoring disease activity

Thank you

GLOMERULAR DISEASESLecture 5

Churg–Strauss syndrome (CSS) is eosinophil-rich and necrotizing granulomatous inflammation often involving the respiratory tract, and necrotizing vasculitis predominantly affecting small vessels, and associated with asthma and eosinophilia. ANCA is more common when GN is present, with an incidence of about 1–3 per 1 000 000.

It characterised by allergic rhinitis, nasal polyposis and lateonset asthma that is often difficult to control. The typical acute presentation is with a triad of skin lesions (purpura or nodules), asymmetric mononeuritis multiplex and eosinophilia.

Pulmonary infiltrates and pleural or pericardial effusions due to serositis may be present. Up to 50% of patients have abdominal symptoms provoked by mesenteric vasculitis.

Churg–Strauss syndrome

Patients with active disease have raised levels of ESR and CRP and an eosinophilia. Although antibodies to MPO or PR3 can be detected in up to 60% of cases, CSS is considered to be a distinct disorder from the other ANCAassociated vasculitides.

Biopsy of an affected site reveals a smallvessel vasculitis with eosinophilic infiltration of the vessel wall.

Management is with highdose steroids and cyclophosphamide, followed by maintenance therapy with low dose steroids and azathioprine, methotrexate or MMF.

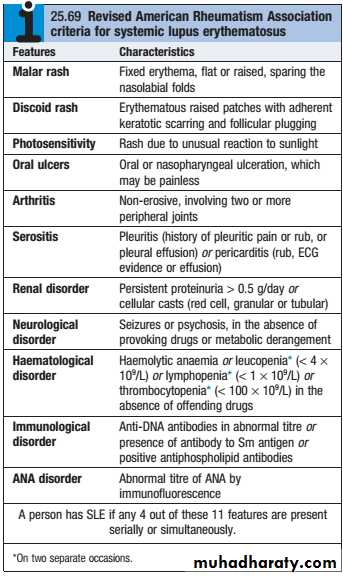

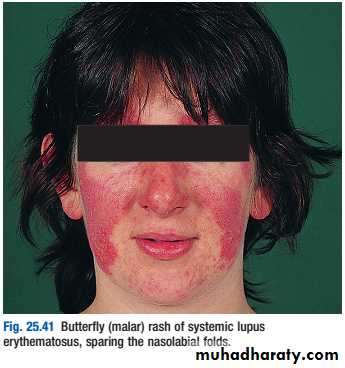

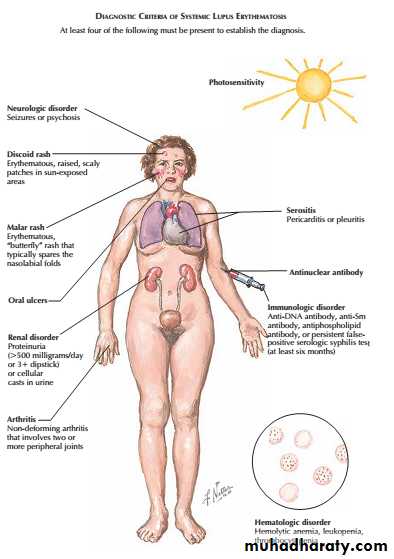

Lupus nephritis (LN) is an immune complex glomerulonephritis that is a common and serious feature of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which itself is defined by a combination of clinical and laboratory features.

Renal involvement is usually manifested by proteinuria, active urinary sediment with microhematuria, dysmorphic erythrocytes and erythrocyte casts, and hypertension. In many cases with major renal involvement, the nephritic syndrome develops in association with proliferative glomerulonephritis (GN) and a decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

Lupus Nephritis

Patients should be screened for ANA and antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens, and have complement levels checked along with routine haematology and biochemistry.

Patients with active SLE almost always test positive for ANA, but ANAnegative SLE can very rarely occur in the presence of antibodies to the Ro antigen. AntidsDNA antibodies are characteristic of severe active SLE but only occur in around 30% of cases. Similarly, patients with active disease tend to have low levels of C3 and C4, but this may be the result of inherited complement deficiency that predisposes to SLE. Studies of other family members can help to differentiate inherited deficiency from complement consumption.

A raised ESR, leucopenia and lymphopenia are typical of active SLE, along with anaemia, haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia.

CRP is often normal in active SLE, except in the presence of serositis, and an elevated CRP suggests coexisting infection.

Treatment :Highdose corticosteroids and immunosuppressants are required for the treatment of life-threatening renal, CNS and cardiac involvement.

A commonly used regimen is pulse methyl prednisolone (10 mg/kg IV), coupled with cyclophosphamide (15 mg/kg IV), repeated at 2–4weekly intervals for six cycles.

Cyclophosphamide may cause haemorrhagic cystitis, but the risk can be minimised by good hydration and coprescription of mesna, which binds its urotoxic metabolites. Because of the risk of azoospermia and anovulation (which may be permanent), pretreatment sperm or ova collection and storage need to be considered prior to treatment with cyclophosphamide.

Mycophenolate mofetil has been used successfully in combination with highdose steroids for renal involvement in SLE, with results equivalent to those of pulse cyclophosphamide but fewer adverse effects.

Following control of the acute episode, the patient should be switched to oral immunosuppressive medication.

A typical regimen is to start oral prednisolone in a dose of 40–60 mg daily on cessation of pulse therapy, gradually reducing to reach a target of 10–15 mg/day or less by 3 months.

Azathioprine (2–2.5 mg/kg/day), methotrexate (10–25 mg/week) or MMF (2–3 g/day) should also be prescribed. The longterm aim is to continue the lowest dose of corticosteroids and immunosuppressant that will maintain remission.

Cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and hyperlipidaemia, should be controlled

(by ACEi+statin) and patients advised to stop smoking.

Lupus patients with the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome who have had previous thrombosis require lifelong warfarin therapy

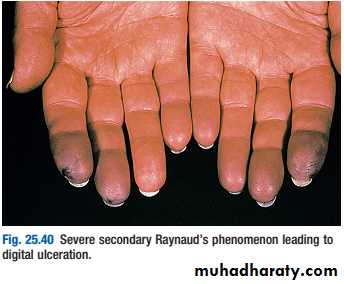

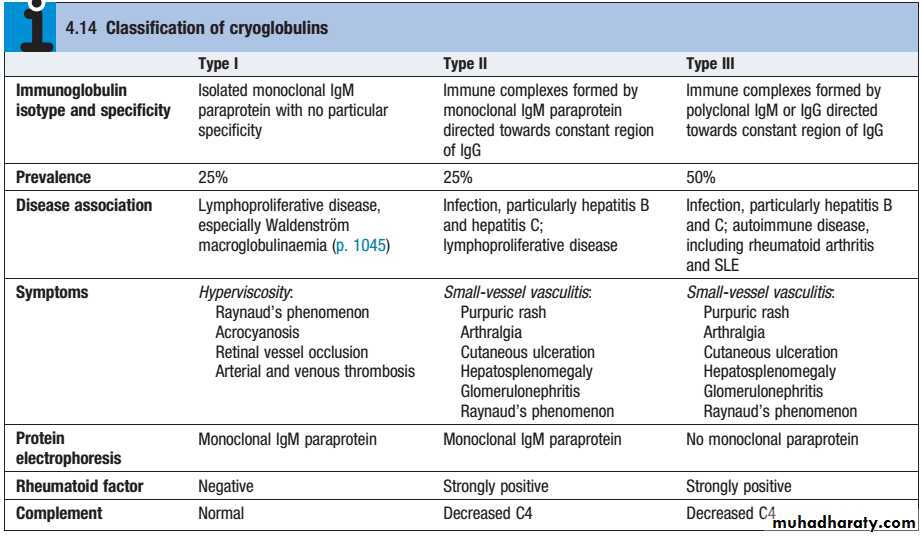

Cryoglobulins (CG)are immunoglobulins and complement components, which precipitate reversibly in the cold.Three types are recognized:

Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis Cryoglobulinaemic renal disease

Presents as purpura, fever, Raynaud’s phenomenon and arthralgias

at least 50% of patients have hepatitis Crenal disease seen in 40% of patients (isolated proteinuria/hematuria progressing to nephritic syndrome)

most patients have decreased serum complement (C4 initially)

treat hepatitis C, plasmapheresis

overall prognosis: 75% renal recovery

Thank you

GLOMERULAR DISEASESLecture 6

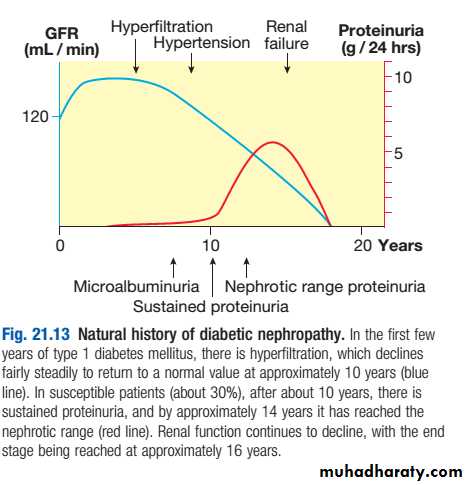

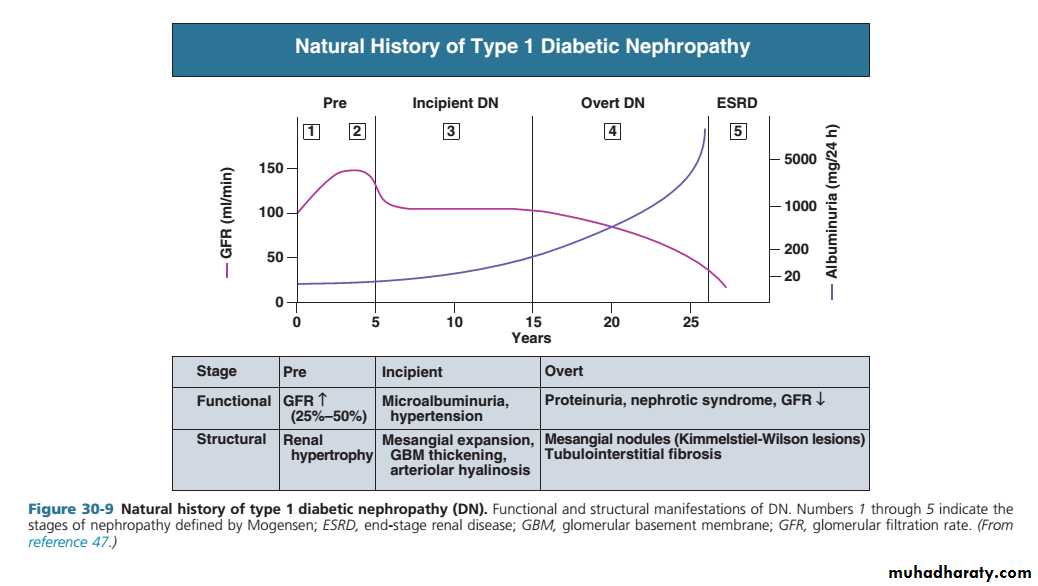

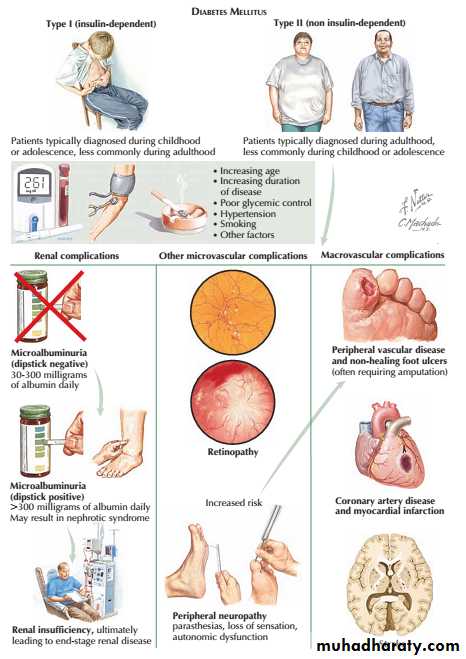

Diabetic nephropathy is an important cause of morbidity and mortality, and is now among the most common causes of end-stage renal failure in developed countries.

About 30% of patients with type 1 diabetes have developed diabetic nephropathy 20 years after diagnosis, but the risk after this time falls to less than 1% per year, and from the outset the risk is not equal in all patients .

Indeed, some patients do not develop nephropathy, despite having long-standing, poorly controlled diabetes, suggesting that they are genetically protected from it.

DIABETIC NEPHROPATHY

• Poor glycaemic control

• Long duration of diabetes

• Presence of other microvascular complications

• Ethnicity (e.g.Asians,Pima Indians)

• Pre-existing hypertension

• Family history of diabetic nephropathy

• Family history of hypertension

Risk factors for diabetic nephropathy:

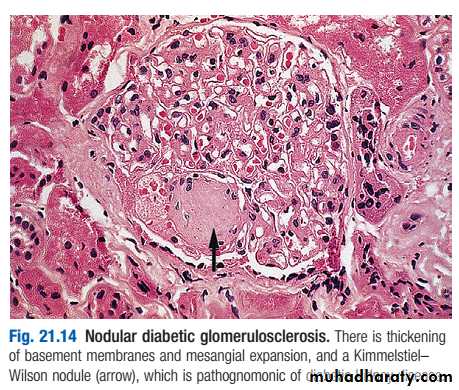

Pathologically, the first changes coincide with the onset of microalbuminuria and include thickening of the glomerular basement membrane and accumulation of matrix material in the mesangium. Subsequently, nodular deposits are characteristic, and glomerulosclerosis worsens as heavy proteinuria develops, until glomeruli are progressively lost and renal function deteriorates.

classic diabetic glomerular lesion: Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodular glomerulosclerosis (15-20%) ,and more common lesion is diffuse glomerulosclerosis with a uniform increase in mesangial matrix

Microalbuminuria is the presence in the urine of small amounts of albumin, at a concentration below that detectable using a standard urine dipstick.

Early morning urine measured for albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR). Microalbuminuria present if:

Males ACR 2.5–30 mg/mmol creatinine

Females ACR 3.5–30 mg/mmol creatinine

Overt nephropathy is defined as the presence of macroalbuminuria (albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) > 300 mg/mmol; detectable on urine dipstick).

Microalbuminuria is a good predictor of progression to nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. It is a less reliable predictor of nephropathy in older patients with type 2 diabetes, in whom it may be accounted for by other diseases , although it is a potentially useful marker of an increased risk of macrovascular disease

Diagnosis and screening

The presence of established microalbuminuria or overt nephropathy should prompt vigorous efforts to reduce the risk of progression of nephropathy and of cardiovascular disease by:

• aggressive reduction of blood pressure

• aggressive cardiovascular risk factor reduction .

In type 1 diabetes, ACE inhibitors have been shown to provide greater protection than equal blood pressure reduction achieved with other drugs, and subsequent studies have shown similar benefits from angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients with type 2 diabetes. This benefit from blockade of the renin–angiotensin system arises from a reduction in the angiotensin II-mediated vasoconstriction of efferent arterioles in glomeruli .

Management

The resulting dilatation of these vessels decreases glomeruli filtration pressure and therefore the hyperfiltration and protein leak. Both ACE inhibitors and ARBs increase risk of hyperkalaemia and, in the presence of renal artery stenosis , may induce marked deterioration in renal function.

Therefore, electrolytes and renal function should be checked after initiation or each dose increase.

Non-dihydropyridine calcium antagonists (diltiazem, verapamil) may be suitable alternatives.

Halving the amount of albuminuria with an ACE or ARB results in a nearly 50% reduction in long-term risk of progression to end-stage renal disease.

Renal replacement therapy may benefit diabetic patients at an earlier stage than other patients with end-stage renal failure.

Renal transplantation dramatically improves the life of many, and any recurrence of diabetic nephropathy in the allograft is usually too slow to be a serious problem, but associated macrovascular and microvascular disease elsewhere may still progress.

Pancreatic transplantation (generally carried out at the same time as renal transplantation) can produce insulin independence and delay or reverse microvascular disease