Hussien Mohammed Jumaah

CABMLecturer in internal medicine

Mosul College of Medicine

Thursday, 7 April , 2016

meningitis

MeningitisAcute infection of the meninges presents with a characteristic combination of pyrexia, headache and meningism.

Meningism consists of headache, photophobia and

stiffness of the neck, often accompanied by other signs of meningeal irritation, including Kernig’s sign (extension at the knee with the hip joint flexed causes spasm in the hamstring muscles) and Brudzinski’s sign (passive flexion of the neck causes flexion of the hips and knees).

Meningitis (continued)

Meningism is not specific to meningitis and can occur in patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage. The severity of clinical features varies with the causative organism, as does the presence of other features such as a rash.Abnormalities in the CSF are important in distinguishing the cause of meningitis.

Infective

Bacteria Viruses• Enteroviruses (echo, Coxsackie, polio)

• Mumps • Influenza • Herpes simplex

• Varicella zoster • Epstein–Barr

• HIV • Lymphocytic choriomeningitis

• Mollaret’s meningitis (herpes

simplex virus type 2)

Causes of meningitis

Protozoa and parasites

• Cysticerci • Amoeba

Fungi

• Cryptococcus neoformans

• Candida • Histoplasma

• Blastomyces • Coccidioides

• Sporothrix

Non-infective (‘sterile’)

Malignant disease

• Breast cancer • Bronchial cancer

• Leukaemia • Lymphoma

Inflammatory disease (may be recurrent)

• Sarcoidosis • SLE • Behçet’s disease

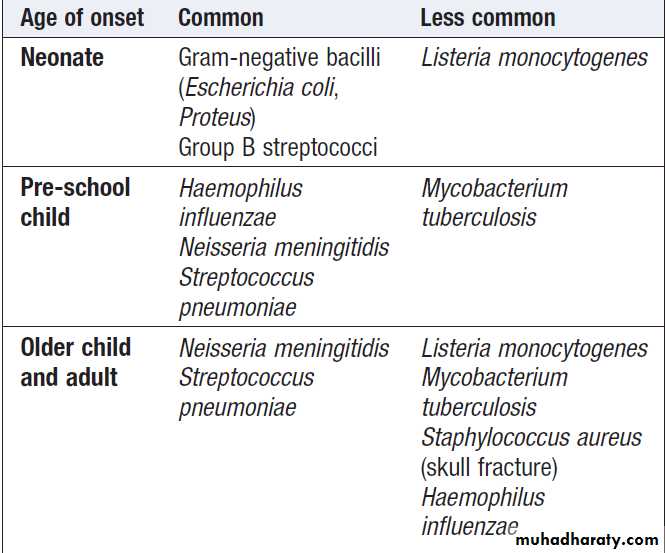

Bacterial causes of meningitis

Bacterial meningitis

Many bacteria can cause meningitis but geographical patterns vary, as does age-related sensitivity . Bacterial meningitis is usually part of a bacteraemic illness, although direct spread from an adjacent focus of infection in the ear, skull fracture or sinus can be Causative. An important factor in determining prognosis is early diagnosis and the prompt initiation of appropriate therapy.The meningococcus and others are normal commensals of the upper respiratory tract.

Bacterial meningitis

PathophysiologyThe meningococcus (Neisseria meningitidis) is now the

most common cause of bacterial meningitis in Western

Europe after Streptococcus pneumoniae, whilst in the

USA Haemophilus influenzae remains common. In India,

H. influenzae B and Strep. pneumoniae are probably the

most common causes of bacterial meningitis, especially

in children. Strep. suis is a rare zoonotic cause of meningitis

associated with contact with pigs. The infection stimulates an immune response, causing the pia–arachnoid membrane to become congested and infiltrated with inflammatory cells.

Bacterial meningitis: Pathophysiology (continued)

Pus then forms in layers, which may later organise to form adhesions. These may obstruct the free flow of CSF, leading to hydrocephalus, or they may damage the cranial nerves at the base of the brain. Hearing loss is a frequent complication. The CSF pressure rises rapidly, the protein content increases, and there is a cellular reaction that varies in type and severity of the inflammation and the causative organism. An obliterative endarteritis of the leptomeningeal arteries passing through the meningeal exudate may produce secondary cerebral infarction. Pneumococcal meningitis is often associated with a very purulent CSF and a high mortality, especially in older adults.Bacterial meningitis

Clinical featuresHeadache, drowsiness, fever and neck stiffness are the usual presenting features. In severe meningitis there may be coma and focal neurological signs. 90% of patients with meningococcal meningitis will have two of the following:

fever, neck stiffness, altered consciousness and rash. When accompanied by septicaemia, it may present very rapidly, with abrupt onset of obtundation due to cerebral oedema.

Chronic meningococcaemia is a rare condition in which the patient can be unwell for weeks or even months with recurrent fever, sweating, joint pains and transient rash.

It usually occurs in the middle-aged and elderly, and in those

who have previously had a splenectomy.

Bacterial meningitis

Clinical features (continued)In pneumococcal and Haemophilus infections there may be an associated otitis media. Pneumococcal meningitis may be associated with pneumonia and occurs especially in older patients and alcoholics, as well as those without functioning spleens. Listeria monocytogenes is an increasing cause of meningitis and rhombencephalitis (brainstem encephalitis) in

the immunosuppressed, diabetic, alcoholics and pregnant . It can also cause meningitis in neonates.

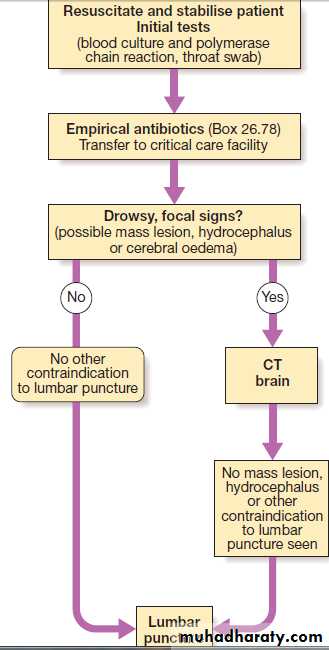

Bacterial meningitis

InvestigationsLumbar puncture is mandatory unless there are contraindications . If the patient is drowsy and has

focal neurological signs or seizures, is immunosuppressed, has undergone recent neurosurgery or has suffered a head injury, it is wise to obtain a CT to exclude a mass lesion (such as a cerebral abscess) before lumbar puncture because of the risk of coning.

This should not, however, delay treatment of a presumptive meningitis.

If lumbar puncture is deferred or omitted, it is essential

to take blood cultures and to start empirical treatment.

Bacterial meningitis

Investigations (continued)Lumbar puncture will help differentiate the causative organism: in bacterial meningitis the CSF is cloudy (turbid) due to the presence of many neutrophils (often > 1000 × 106 cells/L), the protein content is significantly elevated and the glucose reduced.

Gram film and culture may allow identification of the organism.

Blood cultures may be positive. PCR techniques can be used on both blood and CSF to identify bacterial DNA. These methods are useful in detecting meningococcal infection and in typing the organism.

The investigation of meningitis

Bacterial meningitis

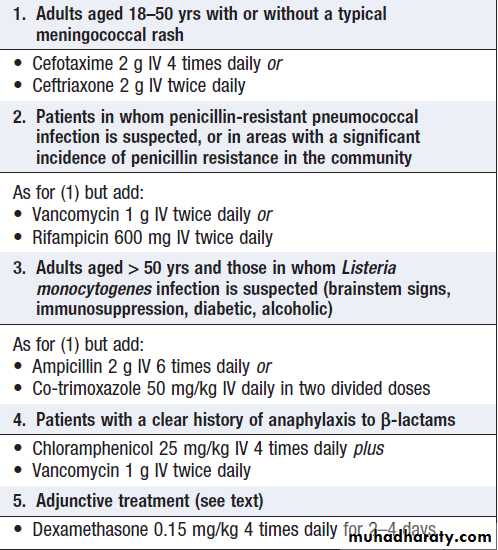

ManagementThere is an untreated mortality rate of around 80%, so action must be swift. If bacterial meningitis is suspected, the patient should be given parenteral benzylpenicillin immediately (IV is preferable) and prompt hospital admission should be arranged. The only contraindication is a history of penicillin anaphylaxis. In meningococcal disease, mortality is doubled if the patient presents with features of septicaemia rather than meningitis.

Bacterial meningitis

Management (continued)Adjunctive corticosteroid therapy is useful in both children and adults in developed countries where the incidence of penicillin resistance is low, but its role in settings where there are high rates of resistance or in under-developed countries where there are high rates of untreated HIV is unclear. Individuals likely to require intensive care facilities.

Adverse prognostic features

include hypotensive shock, a rapidly developing rash, a haemorrhagic diathesis, multisystem failure and age > 60.

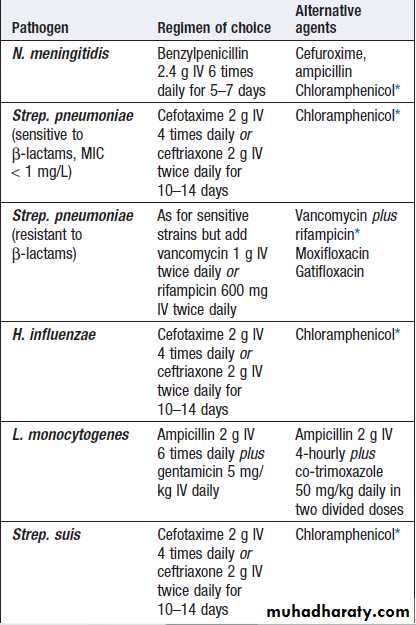

Chemotherapy of bacterial meningitis when the cause is known

*For patients with a history of anaphylaxis to β-lactam antibiotics.

(MIC = minimum inhibitory concentration)

Treatment of pyogenic meningitis of unknown cause

Adjunctive dexamethasone for bacterial meningitis

Prevention of meningococcal infection

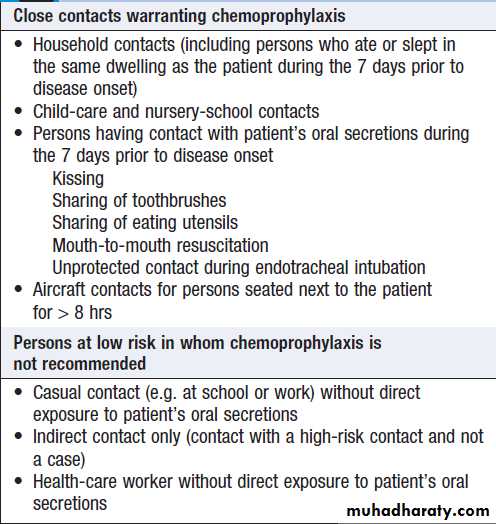

Close contacts of patients with meningococcal infection should be given 2 days of oral rifampicin. In adults, a single dose of ciprofloxacin is an alternative.If not treated with ceftriaxone, the index case should be given similar treatment to clear infection from the nasopharynx before hospital discharge. Vaccines are available for most meningococcal subgroups but not group B, which is among the most common serogroup isolated in many countries.

Chemoprophylaxis following

meningococcal exposureTuberculous meningitis

Tuberculous meningitis

Is now uncommon in developed countries.It remains common in developing countries and is seen more frequently as a secondary infection in patients with AIDS.Pathophysiology

Tuberculous meningitis most commonly occurs shortly

after a primary infection in childhood or as part of

miliary tuberculosis . The usual local source is a caseous focus in the meninges or brain substance adjacent to the CSF pathway. The brain is covered by a greenish, gelatinous exudate, especially around the base, and numerous scattered tubercles are found on the meninges.

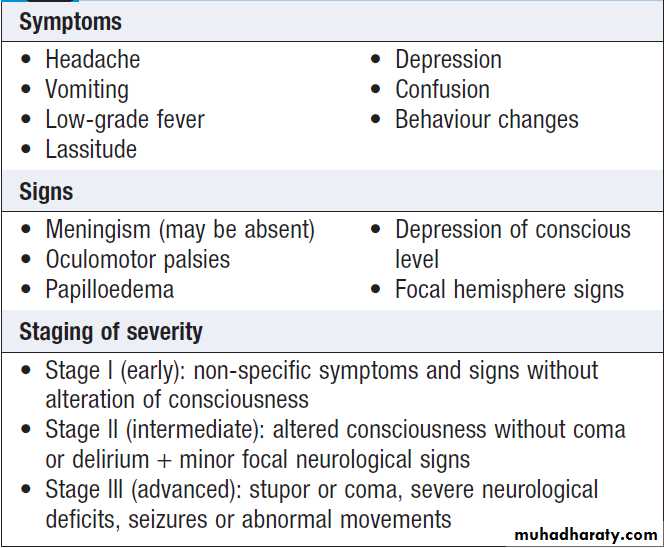

Tuberculous meningitis

Clinical featuresOnset is much slower than in other bacterial meningitis– over 2–8 weeks.

If untreated, it is fatal in a few weeks but complete recovery is usual if treatment is started at stage I .

When treatment is initiated later, the death rate or serious neurological deficit may be as high as 30%.

Clinical features and staging of tuberculous meningitis

Tuberculous meningitis

InvestigationsLumbar puncture should be performed if the diagnosis

is suspected. The CSF is under increased pressure. It

is usually clear but, when allowed to stand, a fine

clot (‘spider web’) may form.

The fluid contains up to 500 × 106 cells/L, predominantly lymphocytes, but can contain neutrophils.

There is a rise in protein and a marked fall in glucose. The tubercle bacillus may be detected in a smear of the centrifuged deposit from the CSF but a negative result does not exclude the diagnosis.

Tuberculous meningitis

Investigations (continued)The CSF should be cultured but, as this result will

not be known for up to 6 weeks, treatment must be

started without waiting for confirmation.

Brain imaging may show hydrocephalus, brisk meningeal enhancement on enhanced CT or MRI, and/or an intracranial tuberculoma.

Tuberculous meningitis

ManagementAs soon as the diagnosis is made or strongly suspected,

chemotherapy should be started using one of the regimens

that include pyrazinamide. The use of corticosteroids in addition to anti-tuberculous therapy has been controversial. Recent evidence suggests that it improves mortality, especially if given early, but not focal neurological damage. Surgical ventricular drainage may be needed if obstructive hydrocephalus develops. Skilled nursing is essential during the acute phase of the illness, and adequate hydration and nutrition must be maintained.

Viral meningitis

Viral meningitis

Viruses are the most common cause of meningitis, usually resulting in a benign and self-limiting illness requiring no specific therapy. It is much less serious than bacterial meningitis unless there is associated encephalitis (which is rare).A number of viruses can cause meningitis , the most common being enteroviruses.

Where specific immunisation is not employed, the mumps virus is a common cause.

Viral meningitis

Clinical featuresViral meningitis occurs mainly in children or young

adults, with acute onset of headache and irritability and the rapid development of meningism. The headache is usually the most severe feature. There may be a high pyrexia but focal neurological signs are rare.

Viral meningitis

InvestigationsThe diagnosis is made by lumbar puncture. The CSF usually contains an excess of lymphocytes but glucose and protein levels are commonly normal; the protein level may be raised. It is extremely important to verify that the patient has not received antibiotics (for whatever cause) prior to the lumbar puncture, as this picture can also be found in partially treated bacterial meningitis.

Viral meningitis

ManagementThere is no specific treatment and the condition is

usually benign and self-limiting. The patient should be treated symptomatically in a quiet environment. Recovery usually occurs within days, although a lymphocytic pleocytosis may persist in the CSF.

Meningitis may also occur as a complication of a systemic viral infection such as mumps, measles, infectious mononucleosis, herpes zoster and hepatitis. Whatever the virus, complete recovery without specific therapy is the rule.