د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنةالبورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2012

Lifetime Risks of Cardiovascular Disease

NEJM January 26, 2012.Background

The lifetime risks of cardiovascular disease have not been reported across the age spectrum in black adults and white adults.Methods We conducted a meta-analysis at the individual level using data from 18 cohort studies involving a total of 257,384 black men and women and white men and women whose risk factors for cardiovascular disease were measured at the ages of 45, 55, 65, and 75 years.

Blood pressure, cholesterol level, smoking status, and diabetes status were used to stratify participants according to risk factors into five mutually exclusive categories. The remaining lifetime risks of cardiovascular events were estimated for participants in each category at each age, with death free of cardiovascular disease treated as a competing event.

Results

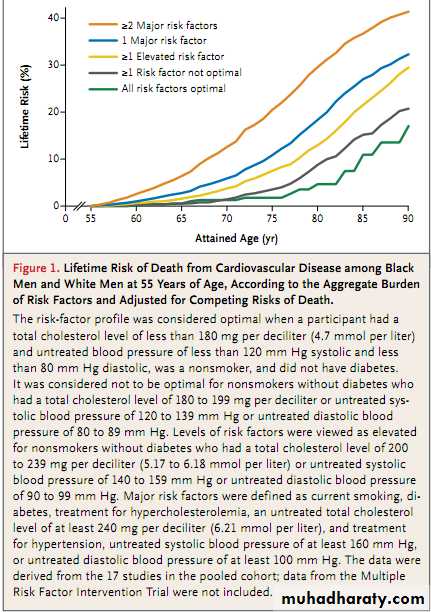

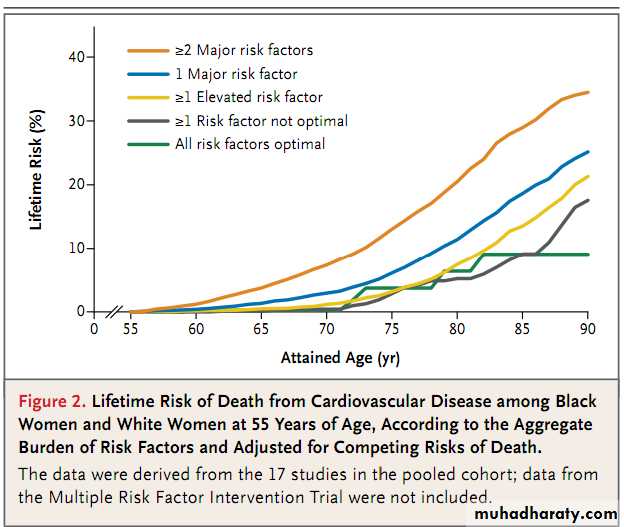

We observed marked differences in the lifetime risks of cardiovascular disease across risk-factor strata. Among participants who were 55 years of age, those with an optimal risk-factor profile (total cholesterol level, <180 mg per deciliter [4.7 mmol per liter]; blood pressure, <120 mm Hg systolic and 80 mm Hg diastolic; nonsmoking status; and nondiabetic status) had substantially lower risks of death from cardiovascular disease through the age of 80 years than participants with two or more major risk factors (4.7% vs. 29.6% among men, 6.4% vs. 20.5% among women).

Those with an optimal risk-factor profile also had lower lifetime risks of fatal coronary heart disease or nonfatal myocardial infarction (3.6% vs. 37.5% among men,

<1% vs. 18.3% among women) and fatal or nonfatal stroke (2.3% vs. 8.3% among

men, 5.3% vs. 10.7% among women). Similar trends within risk-factor strata were

observed among blacks and whites and across diverse birth cohorts.

Conclusions

Differences in risk-factor burden translate into marked differences in the lifetimerisk of cardiovascular disease, and these differences are consistent across race and

birth cohorts. (Funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.)

In this study, we calculated the lifetime risk of

cardiovascular disease according to age, sex, race,

and other risk factors across multiple birth cohorts. There were several important findings.

First, our data strongly reinforce the inf luence of

traditional risk factors on the lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease. Even a relatively low burden

of these risk factors was associated with significant increases in the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease, and the absence of traditional risk factors was associated with a very low lifetime risk.

Second, despite the development of notable

secular trends in the prevalence of risk factorsduring the past 40 years, we observed that the

effect of these factors, when present, remained remarkably consistent across birth cohorts. In addition, although the prevalence of risk factors overall was higher among blacks than among whites, the lifetime risks of end points related to cardiovascular disease were similar among blacks and whites when their risk-factor profiles were similar.

The presence or absence of traditional risk

factors appears to represent a much more consistent determinant of the long-term risk ofcardiovascular disease than race or birth cohort.

For example, among 55-year-old men with two

or more major risk factors, the 20-year adjusted

risk of death from cardiovascular disease was

only 4% lower among men born in or after 1920

than it was among those born before 1920 (16.8%

vs. 20.7%), presumably reflecting the potential

inf luences of subsequent treatment.

In contrast with these modest effects related to birth cohort, the 20-year adjusted risk of death from cardiovascular disease was substantially greater across risk-factor strata. For example, among men born before 1920, those with only one risk factor had a 20-year adjusted risk of death from cardiovascular disease that was 13 percentage points lower than that among men with two or more major risk factors (7.5% vs. 20.7%).

Thus, in the younger birth cohorts, the marked decrease in the proportion of cohort members who were classified in the highest risk group (persons with

two or more major risk factors) appears to account for the majority of the decline in cardiovascular events. We believe these findings have important implications for clinical disease prevention and public health practice. First, the effect of untreated risk factors has been fairly constant for decades.

Therefore, the present estimates of lifetime risk, made on the basis of current or projected risk-factor levels, may be important in estimating the future burden of cardiovascular disease in the general population.

Second, efforts to lower the burden of cardiovascular disease will require prevention of the development of risk factors (primordial prevention) rather than the sole reliance on the treatment of existing risk factors (primary prevention).

Our data are also consistent with earlier observations suggesting that the decline in cardiovascular event rates in the general population reflects changes in the prevalence of risk factors rather than the effects of treatment alone.

For example, 44.3% of the overall decline in U.S. rates of death from coronary heart disease in 1980 and in 2000 was attributed to population

changes in levels of serum total cholesterol (24.2%) and systolic blood pressure (20.1%).

The effects of clinical treatment on these risk factors

were more modest, with statin and antihypertensive therapy accounting for 4.9% and 7.0% of the decline, respectively.We extend these observations to long-term risk estimates, showing that changes in the prevalence of risk-factor profiles strongly inf luence estimates of lifetime risk in the general population.

Prior studies have consistently shown that ahigher burden of risk factors, measured individually or in aggregate, is associated with a markedly higher lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease.However, the majority of these earlier, smaller studies were confined to single cohorts with predominantly white participants.

We believe that our analysis, which is based on pooled data from multiple birth cohorts, with both black participants and white participants and varied

geographic origin, provides more representative

estimates of the lifetime risks of cardiovascular

disease.

Investigators in earlier studies, using standard

methods, have observed that blacks and whites

had similar magnitudes of relative risks for cardiovascular disease events associated with individual risk factors.

Thus, the higher prevalence of adverse risk factors among blacks translates into a higher observed risk of cardiovascular disease. In the present study, we also observed a higher prevalence of risk factors

among blacks than among whites. However, because of the higher burden of competing risks

among blacks, which our analytical approach

accounted for, we observed similar lifetime risks

of death from cardiovascular disease among

blacks and whites, despite the higher burden of

risk factors among blacks.

There are several limitations of the present study. First, our algorithm for aggregate riskfactor stratification included treated patients in

the highest-risk groups. Although the inclusion

of treated patients may have resulted in some

misclassification, these participants represent a

very small percentage of the overall cohort. The

effect of this categorization, if anything, tends

to underestimate future risk in the strata with

the highest risk-factor burden.

Furthermore, we have validated this algorithm in multiple and diverse cohorts, including the Framingham Heart Study, the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry, the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), and the Dallas Heart Study,using diverse clinical and subclinical end points.

We have also observed that the association between risk-factor categories and risk of cardiovascular disease does not depend on the presence or absence of any one risk factor alone. Therefore, we believe that our classification of risk-factor burden provides

a reliable, and conservative, projection of the risk

of cardiovascular disease.

Second, we were not able to estimate lifetime

risks of death from cardiovascular disease for

persons with risk factors measured in the most

recent decade included in the study because the

estimation of lifetime risk ideally requires several decades of actual follow-up from the point

at which the risk factor is measured. Nevertheless, because of the consistency of results across

birth cohorts in which the prevalence of elevated

risk factors varies, we believe that the present

data are applicable to contemporary cohorts.

In summary, the Cardiovascular Lifetime Risk Pooling Project represents a combined analysis of data from more than 250,000 participants derived from 18 cohorts during a period of more than 50 years. We found that the presence of elevated levels of risk factors at all ages translated into markedly higher lifetime risks of cardiovascular disease across the lifespan.

These findings were consistent across risk-factor strata

among both blacks and whites and across multiple birth cohorts.