د. حسين محمد جمعة

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنةالبورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2011

Management of the elderly patientwith aortic stenosis

Heart 2008Aortic stenosis (AS) is now the most frequent heart

valve disease in industrialised countries and itsprevalence sharply increases with age.

Thus,with the lengthening of life expectancy, the

population of old patients with AS is expected to

grow in the future.

Aortic valve replacement (AVR) remains the

reference treatment for severe symptomatic AS and

there are no explicit restrictions for intervention

related to age itself according to guidelines.

However, decision making for intervention is often

difficult in old patients in whom it may not be

obvious whether the benefit of surgery, as compared

to spontaneous outcome, outweighs the risk of intervention.

The literature enables results of AVR to be better

ascertained in the elderly and compared to thenatural history of AS. In addition to their usefulness

in improving decision making for surgery,

surgical series are the reference for the evaluation

of new techniques using transcatheter heart valve

prosthesis. As regards current patient management,

the difficulty is to translate data from the

literature to an analysis of the risk/benefit ratio of

different therapeutic possibilities tailored to the

individual patient.

SPONTANEOUS OUTCOME

Natural history of aortic stenosis

The natural history of AS has been elucidated by

the pioneering work of Ross and Braunwald in the

1960s. The onset of severe symptoms had a major

impact since they were associated with a shortening

of median survival to 5 years.

Median survival was ,2 years in the case of left heart

failure and ,1 year in the case of global heartfailure. These findings remain the basis of the

recommendation to operate on patients with

severe symptomatic AS. However, the extrapolation

of these findings to the elderly with AS may

be debatable. In Ross and Braunwald’s study, death

occurred at an average age of 63 years.

A contemporary series of elderly patients with

severe AS showed that there was a wide range ofsurvival rates in non-operated patients.

The three predictive factors of poor spontaneous outcome were New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV, associated mitral regurgitation, and left

ventricular systolic dysfunction.

The combination of these three factors identified a subgroup atparticularly high risk, with a 3 year survival rate of only 20%.

On the other hand, 3 year survival was over 80% in patients who did not have any of these three factors.

Impact of comorbidities on life expectancy

Comorbidities are frequent in the elderly with AS.This is obviously related to the increased frequency

of comorbidities with age in the general population.

The high frequency of comorbidities related

to atherosclerosis is also explained by the fact that

AS shares a number of common pathophysiological

features and clinical risk factors with atherosclerosis.

Multivariate scores enable the impact of comorbidities

on life expectancy to be assessed. TheCharlson comorbidity index combines comorbid

conditions which are weighed according to their

prognostic impact. More recently, a multivariate

scoring system has been specifically developed and

validated in the elderly. It includes comorbidities

and measures of functional capacity and has been shown to have a good predictive accuracy in the

estimation of 4 year mortality in different age

categories (table 1, fig 1).

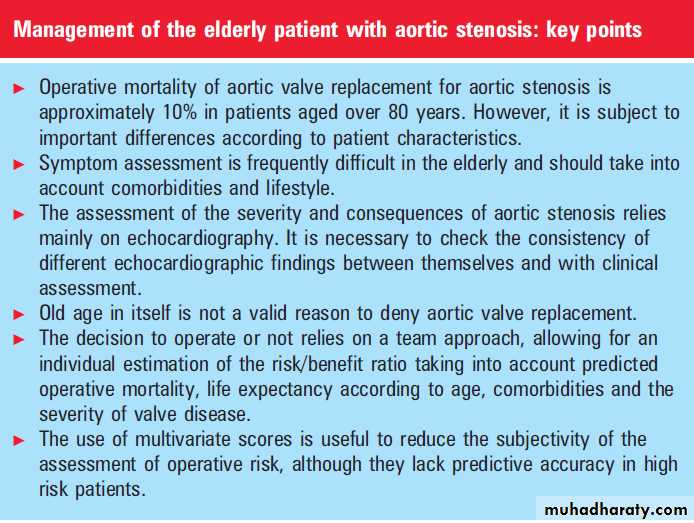

RESULTS OF SURGERY

Operative mortality

A number of contemporary series have reported

the results of AVR in the elderly. Most series

published in the last 10 years have reported

operative mortality rates around 10% in the

octogenarian (table 2).

Like operative mortality,

operative morbidity is higher than in youngerpatients, in particular as regards the frequency of

stroke (between 5–10% in most series).

Postoperative stroke is more frequent in patients

who had associated coronary artery bypass grafting,

which illustrates the impact of associated

atherosclerosis.

Beyond the estimation of mean operative mortality,

risk assessment should be adapted to patientcharacteristics. Large series led to consistent results

demonstrating a strong link between operative

mortality and the following predictive factors:

Advanced stage of heart disease, whether

attested by heart failure, NYHA class IV,

decreased left ventricular ejection fraction, or atrial fibrillation

Comorbidities, in particular chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal insufficiency, or associated atherosclerosis of coronary or peripheral Arteries

Need for urgent surgery.

Associated atherosclerosis plays an important

role given its frequency and implications.

Significant coronary artery disease is present in

approximately half of patients with AS after the

age of 75 years.

It requires coronary artery bypass grafting to be associated with AVR which increases operative mortality in most series.

The likely explanations of this are the increased complexity and duration of intervention and also the fact that patients with coronary artery disease frequently have other locations of atherosclerotic disease which may cause complications.

In particular, patients with coronary artery disease have a higher frequency of postoperative stroke which has an important impact on operative mortality.

The next step to individualise risk assessment is to combine the predictive factors to estimate the operative risk for any given patient. In a series of 675 patients undergoing AVR after the age of 75 years with a mean operative mortality of 12.4%, the predicted operative risk ranged from 5% for elective surgery in patients with few symptoms and normal and left ventricular function to more than 40% in those who underwent urgent surgery in NYHA class IV and had severe left ventricular dysfunction.

Although it did not include comorbidities,the strength of this study was to draw attention to the considerable heterogeneity of operative risk in the elderly.

Individual risk assessment should also take into

account certain patient characteristics which

increase operative risk but are generally not

identified as predictive factors given their rare

occurrence—for example, porcelain aorta (fig 2) or

prior radiation therapy.

Individual risk stratification using scores Multivariate scores have been developed and validated to estimate operative mortality in cardiac

surgery according to cardiac and non-cardiac

patient characteristics. Ideally, they should offer a

compromise between a wide applicability and a

good discrimination.

The Euroscore has been evaluated in general cardiac surgery; however, it has been proven to have a good discriminant power in patients with heart valve disease. Its strengths are to have been widely validated and to be user-friendly.

Other scores have been specifically developed for

heart valve diseases, which would theoretically

ensure better discrimination.12–14 In practice, different scores seem to have relatively close predictive abilities when tested in large populations of

patients with heart valve disease (table 3).

However, scores have limitations when dealing with heart valve diseases in the elderly.

Discrepancies between predicted and observed operative mortality have been described in patients with AS and are more pronounced in high risk patients.The reduced predictive ability of multivariate scores in high risk patients is probably related to the fact that high risk groups accounted only for a small proportion of the populations from which scores were elaborated. In addition, high risk patients form a particularly heterogeneous group, in which it is difficult to estimate accurately the individual contribution of each factor to operative mortality.

Late results of aortic valve surgery After the postoperative period, late results of AVR

are good in the elderly. Five year survival rates areestimated at between 50–70% after AVR in the

octogenarian.

Of course, survival rates are lower than in younger patients, but they favourably compare with life expectancy in a general population of the same age. Related survival—that is, compared to the expected survival—is particularly good in the elderly.

As with operative mortality, late mortality after

AVR is related to the evolution of heart diseasebefore surgery (heart failure) and comorbidities.

Surgery also gives good results as regards quality

of life. Elderly derive at least the same benefits as

younger patients as regards physical activity,

depression, and global indices of quality of life.

The wide use of bioprostheses in this age range

contributes to the absence of constraints directly

related to valve surgery.

PATIENT MANAGEMENT

Patient evaluation

The number of patient characteristics which have an impact on the results of surgery as well as on spontaneous outcome underline the need for athorough patient evaluation. It is necessary to spend time on the analysis of case history. Symptom onset, which is the main factor leading to consider surgery, is often difficult to determine in the elderly since patients may have reduced their activity by themselves or because of associated diseases. Fatigue, rather than dyspnoea,can be the sign of limited effort tolerance. Case

history also enables comorbidities, lifestyle, and

patient’s wishes to be assessed.

Cardiac auscultation should pay attention to the

abolition of the second heart sound, which isspecific to severe AS and is particularly helpful

when the murmur is of low intensity. Echocardiographic examination is the cornerstone to confirm the diagnosis of AS, and assess its severity and its consequences on the left ventricle.

It is of utmost importance to check for the consistency of different findings between themselves and with clinical assessment. Valve area below 0.6 cm2/m2 of body surface area is a marker of severe AS and it has the advantage of taking into account body size.

Despite its flow dependence,aortic gradient should also be taken into account since it is less subject to errors of measurements.

Amean aortic gradient over 40–50 mm Hg indicates severe stenosis.

Coronary angiography is indicated before surgery

and is also an important component of decision making, given the implications of coronary disease on operative risk and prognosis. Noninvasive assessment using computed tomography may emerge as a valid method for the comprehensive evaluation of coronary anatomy as well as

valve area and left ventricular function.

However, the predictive value of computed tomography for coronary disease remains suboptimal in this

population where the prevalence of coronary

disease and coronary calcification is high.

Cardiac catheterisation is seldom needed to assess valve disease. It should be performed only in the rare

cases where non-invasive assessment is inconclusive,

and should not be systematically associated

with coronary angiography. Other investigations are indicated according to clinical evaluation, in particular as regards comorbidities.

Decision making

Therapeutic decisions should be based on a risk–

benefit analysis weighing the operative risk against

the benefit of surgery as compared to the spontaneous outcome of AS. This decision should also take into account the patient’s life expectancy and quality of life regardless of AS. This analysis is particularly difficult in the elderly with AS given the heterogeneity of operative risk and spontaneous prognosis.

Despite their limitations, in particular in high risk patients, the interest of multivariate scoring systems is to combine a number of patient characteristics to reduce the subjectivity of the assessment of operative risk and life expectancy.

Of course, they only represent an aid for decision

making and should be integrated with many other

factors in clinical judgement.

The benefit of surgery on late outcome should be

interpreted in the light of life expectancy, whichmay be more compromised by age itself than by

AS. For example, life expectancy in France at the

age of 85 is 5 years for a man and 6 years for a

woman, which is close to life expectancy after

symptom onset in AS.

Unlike in young patients, the main purpose of surgery in the elderly is to improve symptoms rather than to increase the duration of life. This explains why surgery is generally not considered in asymptomatic AS in the elderly since the operative risk is not justified by the spontaneous outcome.

Besides their negative impact on operative mortality and life expectancy, certain comorbidities,

such as respiratory insufficiency or neurological

dysfunction, compromise the improvement of

quality of life following cardiac surgery. Improvements in the knowledge of the different elements of decision making underline the importance of clinical judgement, which should take into account not only many patient characteristics but also their wishes and expectations.

The final decision to operate or not should be taken

according to a joint approach involving the cardiac

surgeon, anaesthetist, cardiologist, and geriatrician

if needed. This evaluation should lead to thorough

assessment of the patient’s wishes as well as

information of the patient and relatives.

Difficulties in decision making in the elderly with AS are not only related to the decision to operate or not, but also to the timing of surgery.

Given the operative risk and the frequent reluctance

of patients, it is seldom decided to consider surgery at the very beginning of symptoms.

Symptoms are often difficult to interpret in the elderly and this tends also to defer the time at which surgery will be considered.

Of all factors increasing operative mortality, the severity of symptoms is the only one on which clinicians can act by avoiding too late a decision for surgery.

Therefore, it is of importance to weigh its risk and

benefits at the onset of symptoms. This helps to

avoid taking the decision in a patient with an

advanced disease in an urgent situation, which

increases operative mortality.

Modalities of intervention

A bioprosthesis is the substitute of choice in theelderly. Elderly women with AS frequently have a

small aortic annulus size, which may favour

patient–prosthesis mismatch. However, this does

not seem to have a major impact in the elderly,

unlike in patients with left ventricular dysfunction.

Coronary artery bypass grafting should be

combined in case of significant coronary disease.

However, surgery should not be denied when

severe symptomatic AS is associated with nonbypassable coronary disease. A hybrid approach

combining preoperative coronary angioplasty and

isolated AVR is feasible. However, this approach

raises particular problems regarding the management

of antiplatelet drugs after stenting and its

results have not been evaluated in large series.

THERAPEUTIC ALTERNATIVES IN NON-OPERATED

PATIENTSTwenty years ago, balloon aortic valvuloplasty

emerged as a promising alternative for the treatment

of AS in high risk patients.

However, despite frequent functional improvement, there was only alimited and transient improvement in valve function.

More importantly, balloon aortic valvuloplasty did not improve survival as compared with natural history.

Therefore, risk–benefit analysis does not support balloon aortic valvuloplasty as an alternative to surgery. This explains why guidelines restrict indications for balloon aortic valvuloplasty to situations in which it is used as a bridge for subsequent AVR.

Percutaneous implantation of a transcatheter heart valve prosthesis now seems to offer the possibility of a durable improvement in valve function at a lower risk than AVR.

Growing experience and ongoing trials in patients at high operative risk, but whose life expectancy is not compromised in the short term, will allow more accurate evaluation of the clinical benefit of the procedure. For ethical reasons, the first cases were performed only inpatients who had contraindications to surgery because of end stage heart disease and/or severe comorbidities.

This accounted for high mid term mortality rates; however, it demonstrated the feasibility of this approach. When the prosthesis cannot be delivered using an endovascular approach because of the peripheral artery status, it is possible to insert the prosthesis using a minimally invasive, transapical, surgical approach.

Finally, in patients with AS who would not undergo any intervention, medical treatment should be adapted to symptoms.

No medical treatment has been shown to improve the prognosis of AS. Retrospective studies suggested that statins may slow the progression of AS but this has not been confirmed by the only randomised trial published so far.

WHAT HAPPENS IN CURRENT PRACTICE?

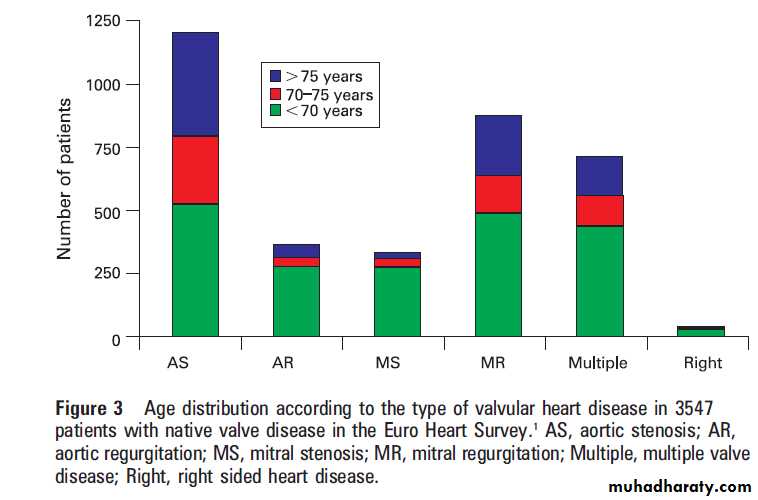

The Euro Heart Survey on valvular heart diseaseprovided information on the contemporary characteristics

and management of patients with AS.1

Even more than in the general population, AS was

by far the most frequent heart valve disease in the

elderly (fig 3).

Of the 216 patients aged >75 years who had

severe symptomatic aortic AS, 72 (32%) weredenied surgery. The two patient characteristics

associated with a decision not to operate as

assessed by multivariate analysis were left ventricular

dysfunction and older age. On the other

hand, comorbidities combined in the Charlson

comorbidity index were not significantly associated

with the decision to operate or not.

It can be understood that clinicians are reluctant

to consider surgery in patients aged over 85 or in

those with major left ventricular dysfunction

(ejection fraction (30%), who accounted for only

a small proportion of the population, however. The

strong relationship between surgical denial in

patients aged between 80–85 years and those with

left ventricular ejection fraction between 30–50% is

not supported by risk–benefit analysis, in particular

in the absence of comorbidities.

These patients are likely to derive a particular benefit from surgery in terms of duration and quality of life as compared with spontaneous outcome.

On the other hand, it is surprising that the Charlson comorbidity index was not significantly associated with the decision not to operate. Most comorbidities increase the

operative risk and are also associated with asignificant decrease in life expectancy and have,therefore, a negative impact on the risk/benefit ratio of AVR.

CONCLUSION

The difficulties in the management of AS in theelderly are greatly related to the heterogeneity of

operative risk and spontaneous outcome. This is

the consequence of the diversity of patient

characteristics.

Validated multivariate scores aiming to assess operative mortality and life expectancy represent an aid to decision making.

Their use should be encouraged to improve current

practices according to guidelines. This may avoid

patients being denied surgery only because of age

or left ventricular dysfunction, as well as allowing

for a better consideration of the impact of

comorbidities. The availability of less invasive techniques,

combined with lengthened lifespan, is likely to

increase the referral of elderly with AS presenting

with a high risk profile.

This challenging perspective stresses the need for a thorough evaluation of new techniques and also a better knowledge of the natural history of AS in the elderly and its determinants.

The predictive value of multivariate predictive scores should be improved to guide the individual choice between AVR, less invasive techniques, or abstention. It remains that the final therapeutic decision can rely only on clinical judgement based on a team approach.

This is mandatory in order to individualise decision making according to the expected risks and benefits of

the different treatments and the wishes of the

informed patient.