Triple antithrombotic managementafter stent implantation: when and how?

Heart 2009د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2011

Inhibition of platelet activation is a cornerstone of

adjunctive medical treatment during and afterpercutaneous coronary interventions with stent

implantation (PCI-S) in order to prevent acute and

long term thrombotic complications.

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAT) with aspirin and clopidogrel has been proven to be very effective at

preventing adverse events such as acute and

subacute stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction,

and death after coronary stenting, for both bare

metal stents (BMS) and drug eluting stents (DES).

Oral anticoagulation (OAC) is the recommended

treatment for patients at risk of thromboembolic events due to atrial fibrillation, mechanical heart valves, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism and left ventricular thrombi. The number of patients who have an indication for both DAT and OAC is increasing, since more patients who are already on OAC are scheduled for percutaneous coronary interventions and some patients who are on DAT will develop a medical condition which requires OAC.

Consequently, these patients need triple antithrombotic therapy, consisting of aspirin, clopidogrel and OAC. There is a concern, however, that this ‘‘triple therapy’’ leads to increased bleeding events and physicians are

cautious in prescribing the combination of DAT

and OAC.

Compared to the combination of aspirin and OAC,

DAT is superior in reducing thrombotic events (stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction) and in reducing haemorrhagic complications. Consequently, clopidogreltogether with aspirin is the current recommendation

for antithrombotic therapy after coronary

stenting, regardless of the type of stent (DES or

BMS). The recommended duration of this DAT,

however, depends on the type of stent.

In patients treated with a BMS, the recommended

minimal duration of DAT after implantationof a coronary stent is 4 weeks. After that time

period, it is assumed that the stent struts are

sufficiently endothelialised, and stent thrombosis

is a rare event. Consequently, DAT can be

discontinued and a single antiplatelet therapy with

aspirin or clopidogrel can be continued.

The rapid re-endothelialisation of BMS struts is often accompanied by a significant degree of neointimal

hyperplasia which may predispose to restenosis

and necessitate repeat coronary interventions.

With DES the neointimal hyperplasia of the

stented segment can be effectively inhibited and

the need for repeat revascularisation procedures

can be significantly reduced.

The current guidelines recommend at least 12 months of DAT after DES implantation.

However, some studies suggest that discontinuationof clopidogrel is a major determinant of

stent thrombosis only in the first 6 months after

stent placement. Whether the optimal duration of

DAT after DES placement will be 6 or 12 months

(or even longer) is currently unclear and under

investigation.

One multicentre, randomised study has been started to compare prospectively 6 and12 months of DAT after DES in 6000 patients (ISAR-SAFE, Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Safety And eFficacy of a 6-month DAT after drug-Eluting stenting).

INDICATION AND DURATION OF ORAL

ANTICOAGULATIONAtrial fibrillation is the most frequent reason for long term OAC, accounting for 70% of the patients on OAC scheduled for PCI-S. The overall prevalence of atrial fibrillation in patients over 60 years is 4%. The prevalence rises to 9% in patients over 80 years. It is forecast that, due to an increasing population age profile, the number of patients with atrial fibrillation will have more than doubled by 2050.

Multiple randomised trials have evaluated the efficacy and safety of OAC or aspirin for stroke

prophylaxis in atrial fibrillation and have shown

that OAC is superior to aspirin in reducing stroke

in patients with atrial fibrillation. This reduction

of strokes was significantly higher than the

increase in major bleedings by OAC. OAC has also

been compared to DAT in a large randomised trial

and has been shown to have superior efficacy in

preventing strokes.

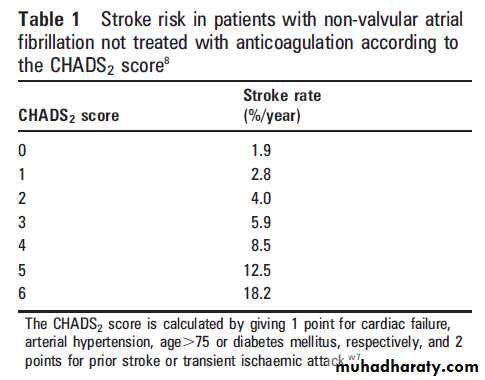

However, the net benefit of OAC in patients with atrial fibrillation strongly depends on the individual absolute risk for stroke and bleeding. The CHADS2 score, which includes cardiac failure, arterial hypertension, age, diabetes mellitus, and previous stroke, is the most commonly used model to risk stratify patients (table 1). Patients with a CHADS2 score (1 are at low risk for stroke and can be treated with aspirin (or DAT in case of PCI-S).

Patients with aCHADS2 score >2 may be expected to derive incremental benefit from OAC (international normalised ratio (INR) 2.0–3.0), since the individual risk for stroke gradually outweighs the annual risk for major bleeding, which may be assumed to be 1–2% (table 1).

Venous thromboembolism

The current treatment for prevention of venousthromboembolism, is OAC. There are no

studies demonstrating that aspirin or DAT is equivalent to OAC in the prevention of venous thromboembolism. However, in contradistinction

to atrial fibrillation, the recommended duration of

OAC for venous thromboembolism is limited in

many patients. In these patients, an elective PCI-S

may be postponed to avoid the need for DAT and

OAC at the same time.

Current recommendations suggest that OAC should be maintained for 3–6 months in patients with transient risk factors for venous thromboembolism (for example, immobilisation)and for more than 12 months for recurrent venous thromboembolism. While the appropriate duration of OAC for idiopathic or recurrent thromboembolism is not definitely known, there is evidence of substantial benefit for extended

duration treatment. Patients with inherited thrombophilias should receive lifelong anticoagulation

in the case of life threatening thromboembolic

events or recurrent thrombosis.

Mechanical heart valves

Patients with mechanical heart valves are amongthose with the highest risk for thromboembolic

events without OAC. The event rates for systemic

embolism per 100 patient-years is 8.6 without

antithrombotic therapy, 7.5 with aspirin alone, and

1.8 with coumarins. Only one study has so far

assessed the safety and efficacy of DAT compared

to OAC and was terminated early because of a

higher rate of valve thrombosis in the DAT group.

Therefore, the current recommended treatment to

prevent thromboembolic events in patients with

mechanical valves is OAC.

Ventricular thrombi

The presence of a left ventricular thrombus may bean indication for OAC to prevent systemic emboli.

The risk of systemic embolisation can be reduced

with OAC. To our knowledge, there are no data

on the use of DAT to prevent systemic embolisation

in patients with ventricular thrombi.

The guidelines state that OAC should be prescribed for at least 3 months, and indefinitely in patients

without an increased risk of bleeding. In the case

of PCI-S and the need for DAT, the benefit of OAC

should be estimated taking into account the

probable age of the ventricular thrombus and any

prior history of systemic emboli.

Heart failure

Some studies have shown that aspirin as well asOAC reduce stroke in patients with low ejection

fraction, while others could not demonstrate

a beneficial effect with either agent.

Accordingly, the current guidelines for heart failure

do not support the general use of OAC in those

patients with heart failure and no history of atrial

fibrillation or a prior thromboembolic event.

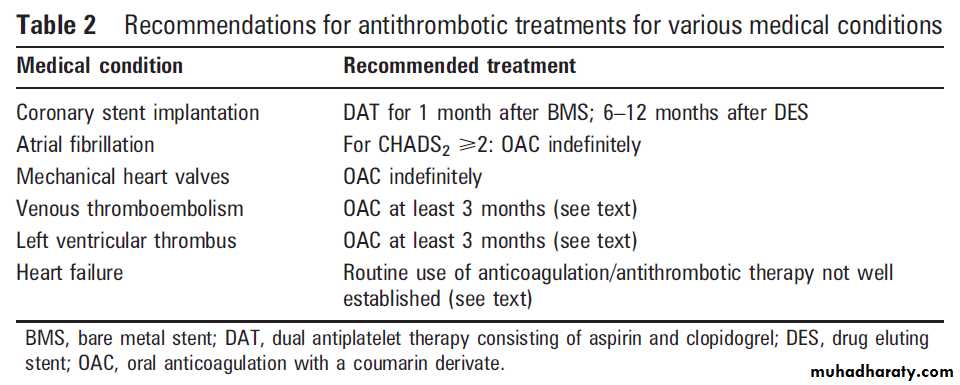

An overview of these recommendations in the

various medical conditions discussed above is

presented in table 2.

STUDIES ON TRIPLE THERAPY

The prevalence of patients on OAC scheduled fora percutaneous coronary intervention strongly

depends on the population screened. In one retrospective analysis of more than 4000 patients, 6%

required long term OAC.

At our institution, 5–10% of all patients scheduled for percutaneous coronary intervention were on OAC.

Since the mean age of patients undergoing PCI-S is likely to become progressively older, and the prevalence of atrial fibrillation—the principal indication for OAC—is strongly related to the age of the patients,we expect to encounter an increasing number of patients scheduled for PCI-S who have an indication for OAC.

Therefore, at least for a certain time period,these patients have an indication for both DAT

and OAC. As demonstrated in 6706 patients of the

ACTIVE W (Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial

with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events)

study, DAT and OAC treatment are each associated

with nearly 15% risk of major or minor bleeding per year. As each regimen impairs haemostasis by a different mechanism, there is aconcern that adding OAC to DAT may increase bleeding rates.

On the other hand, temporary discontinuation of either antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy in this subset of patients may increase the risk of either stent thrombosis

or thromboembolic events, as discussed above.

Therefore, the benefit and risk of triple therapy for

patients undergoing PCI-S while on OAC is an

important consideration.

For some patients, concomitant treatment with OAC and DAT may be avoided by delaying PCI-S to a time point when OAC will be no longer indicated.

For most patients, however, OAC is a lifelong recommendation, and therefore postponing PCI-S is not an option.

Several studies have so far assessed patients on

OAC who underwent PCI-S. Triple therapy wasone treatment option in these patients. Most of

the studies were retrospective studies or post hoc

analyses of prospective registries. Some

of the studies included a control group which was

treated with DAT. However, in all of these studies

neither the patients with an indication for OAC

were uniquely treated with triple therapy nor the

control group was treated in a standard manner.

When discussing the evidence for patients on triple

therapy it is important to realise that none of the

studies prospectively evaluated the treatment

options for patients with stent implantation on

OAC in a randomised manner.

Bleeding events :

Combined major and minor bleeding events in these studies varied from

9.2–27.5% for patients on triple therapy.

The rates for bleeding events varied from study to study, as follow-up times, bleeding definitions and baseline characteristics of patients on triple therapy were different.

Whether these rates for bleeding events in patients

on triple therapy are significantly ‘‘increased’’

depends on the definition of the control group.

Does it comprise patients on warfarin alone,

warfarin + aspirin, warfarin + clopidogrel, or

DAT? Some of the studies included a control

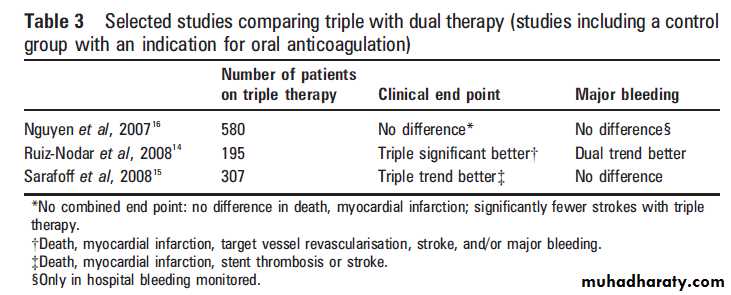

group without an indication for OAC. In only three studies, patients on triple therapy as well as the control group had an indication for OAC.

Since only patients with an indication for

OAC are candidates for triple therapy, the resultsof these latter three studies are of the greatest

relevance (table 3).

One study16 reported similar inhospital rates for major bleeding in patients with triple therapy (5.9%) compared to warfarin plus asingle antiplatelet drug (4.6%);

in agreement with this, another study reported similar rates for major and minor bleeding after 2 years in patients with triple therapy (9.1%)

versus DAT (11.5%);

and one study showed a non-significant trend

towards increased major as well as minor bleedings

after a median follow-up of 595 days in patients on

OAC (27.5%) versus DAT (18.0%).

A recent review article on triple therapy has also included the studies with matched control groups and has found that the bleeding risk with triple therapy

was consistently higher at 1, 6 and 9 months.

Most of the bleeding occurred in the gastrointestinal

tract. Taken together, the risk for bleeding in

patients on triple therapy might be increased when

compared to DAT. It is not possible, however, to

calculate a ‘‘relative risk’’ for bleeding on the basis

of the published data.

Cardiovascular events

With regard to efficacy, stent thrombosis as well asthromboembolic events should be taken into

account when comparing triple therapy with other

treatment options for patients on OAC undergoing

PCI-S. In the two studies comparing triple therapy

with DAT for more than 30 days, thromboembolic

events and death were increased when patients

were on DAT instead of triple therapy, while

subacute or late stent thrombosis were not different.

In another study in which multiple antithrombotic treatment strategies were evaluated

for 12 months in patients with stent implantation

and an indication for OAC, the patients on

DAT had the highest incidence of stroke (8.8% vs

2.8% in patients on triple therapy) and the patients

on warfarin and aspirin had the highest incidence

of stent thrombosis (15.2% vs 1.9% in patients on

triple therapy).

At least for longer follow-up periods (>30 days), the efficacy of triple therapy to prevent thromboembolic events appears to be significantly higher compared to DAT, and the efficacy of triple therapy to prevent subacute stent thrombosis seems to be higher compared to warfarin without DAT.

MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS RECEIVING TRIPLE

THERAPYManaging patients on triple therapy is a difficult

task and the following issues should be considered:

What kind of stent should be used?

Which target INR should be aimed for?

Is there a benefit for adding proton pump inhibitors to protect against gastrointestinal bleeding?

We will briefly discuss the rationale for each of

these measures and provide guidance on how to

implement them in the management of an individual patient.

Low INR levels

There is some evidence that maintaining INR at

the lowest possible level will significantly reduce

the risk for bleeding in patients on triple therapy,

without losing the efficacy to prevent thromboembolic events. Our own data suggest that an INR of

2.5–3.0 in patients with mechanical valves and an

INR of 2.0–2.5 for all other indications may lead to

comparable rates of major bleeding in patients

with triple therapy compared to DAT.

Another study has shown that aiming for a target INR of 2.0–2.5 leads to a significant decrease in major and minor bleeding events in patients treated with triple therapy.

Therefore, it is our practice and the

recommendation of the current guidelines to

recommend an INR at the lowest possible level

during the time period of triple therapy.

An important implication of this practice is that the

frequency of blood sampling should be increased if the INR is to be safely maintained in this narrower range.

Proton pump inhibitors

Since gastrointestinal bleeding accounts for about30–40% of haemorrhagic events in patients on

triple therapy, consideration of approaches to

reduce the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding is

relevant. For the period that triple therapy is

needed, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding should

be reduced by a concomitant treatment with

proton pump inhibitors.

It has been shown that omeprazole has a negative effect on clopidogrel mediated platelet reactivity.

Although the impact of this effect on clinical end points has so far not been investigated, the use of proton pump inhibitors other than omeprazole for patients on triple

therapy might be advisable.

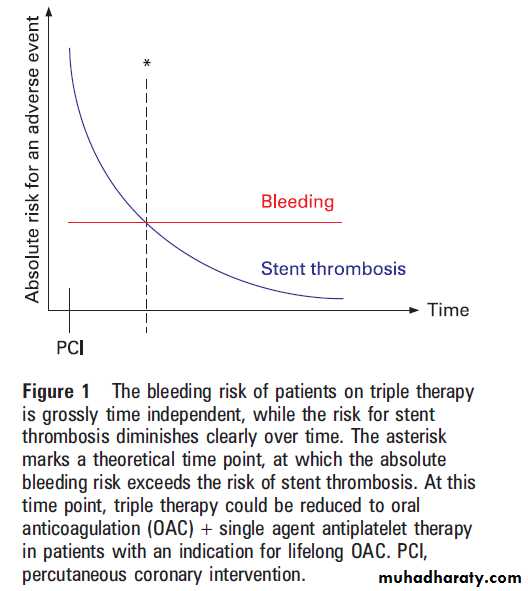

DES versus BMS in triple therapy

While the bleeding risk of patients on tripletherapy remains the same over time, the risk of

stent thrombosis diminishes with time (fig 1).

This is supported by an observational study which

demonstrated a continuous risk for bleeding, while

the stent thrombosis events mostly occurred early

after percutaneous coronary intervention.

Since DES and BMS differ in terms of endothelialisation

and the recommended duration of DAT to preventsubacute stent thrombosis, it has been proposed

that BMS should be the preferred stent type so that

the duration of triple therapy might be limited to

4 weeks. So far no study has primarily addressed

the outcome of patients with BMS compared to

DES and an indication for OAC.

In general, target lesion revascularisation is significantly reduced with DES compared to BMS. While all reinterventions carry an additional risk, especially in patients on OAC, it is unclear what the net effect is when it comes to a reduced duration of triple therapy compared to a reduced rate of target lesion revascularisation.

As long as this question has not be justified. On the other hand, if the consequences of an occluded vessel caused by a stent thrombosis are low, since the jeopardised myocardium is small,an even shorter duration of triple therapy of 4 weeks might be justified.

Until prospective data are available, triple therapy after DES is limited to 3 months in our institution, followed by OAC plus aspirin or clopidogrel in patients with a strong indication for lifelong OAC.

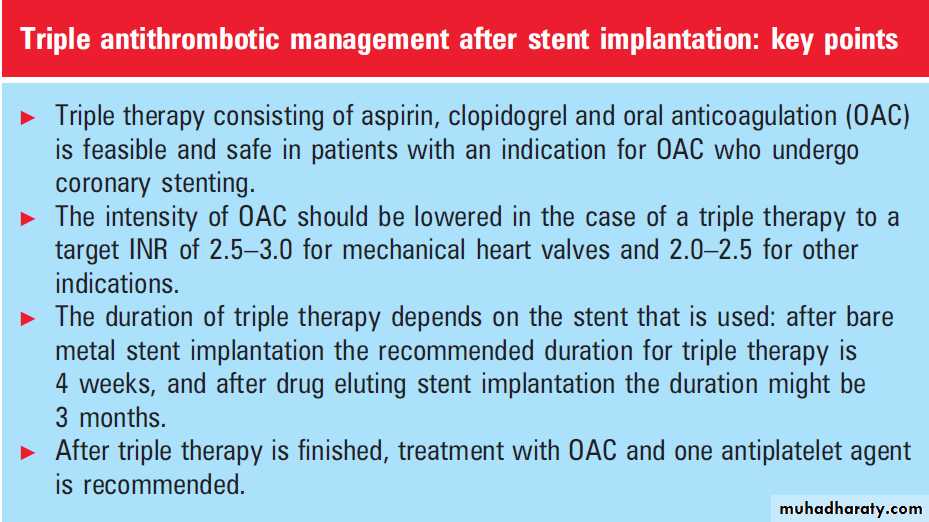

CONCLUSION

When and how should physicians prescribe tripleantithrombotic therapy—consisting of warfarin,

aspirin, and clopidogrel—after stent implantation?

Triple therapy is the best treatment option in

patients with an indication for OAC and an

intermediate to high risk for thromboembolic

events who undergo coronary stenting.

Indications for OAC with an intermediate to high

risk for thromboembolic events includeatrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score>1, mechanical heart valves,

recent venous thromboembolism, or

new ventricular thrombi.

When DES are used, the duration of triple therapy might be limited to3 months.

BMS implantation with triple therapy for 1 month is an alternative in patients who have an excessive risk for bleeding.

To reduce bleeding complications, a low INR (2.5–3.0 for mechanical heart valves and 2.0–2.5 for other indications) should be targeted during triple therapy, with the recommendation for more frequent monitoring.

Proton pump inhibitors are recommended in

patients who receive triple therapy.

These recommendations for triple therapy are

based on the limited data that are available thus far.The current European and US guidelines for

percutaneous coronary intervention do not comment

in detail on patients with an indication for

OAC due to the lack of published evidence on what

the optimal management strategy is for these

patients. Therefore, further prospective clinical trials

are needed in order to evaluate the best treatment

strategy for patients on OAC who undergo percutaneous coronary interventions. Some of them are

already under way (AFCAS, ISAR-TRIPLE).