Insulin-Pump Therapy for Type 1Diabetes Mellitus

nejm. org april 26, 2012د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2012

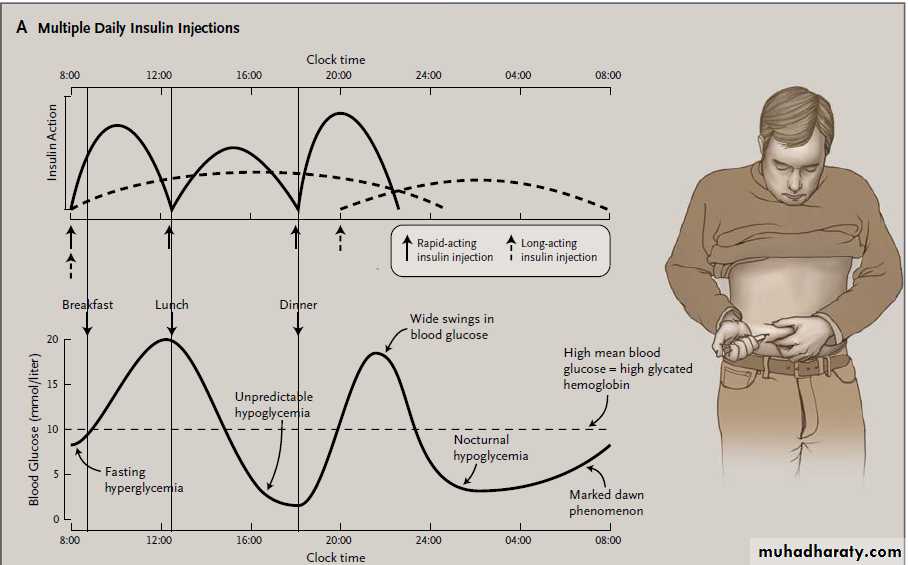

The Clinical Problem It is now well established that the serious microvascular complications of diabetes are linked to the duration and severity of hyperglycemia; there have therefore been renewed efforts to help patients achieve near-normal blood glucose levels. The mainstay of current management of type 1 diabetes is “physiological insulin replacement,”

the main example of which is the practice of administering multiple daily injections of insulin.

Several organizations have set targets for glycemic

control; for example, the American Diabetes Association recommends a general goal for glycated hemoglobin levels of less than 7%, though it recommends less stringent targets for some persons.However, in everyday clinical practice, it is

widely recognized that such targets are easier to set than to achieve.4 In a Scottish registry of 24,750 patients with type 1 diabetes,5 only 7% had a glycated hemoglobin level of less than 7%, and in an Australian survey of patients with type 1 diabetes, 4 13% had a glycated hemoglobin level of less than 7%.As glycemic control improves with intensified insulin regimens, the frequency of hypoglycemia tends to increase. Hypoglycemia is the cause of considerable stress and anxiety, impaired well-being, and poor quality of life in patients with type 1 diabetes, and 35 to 40% of patients with type 1 diabetes regularly have an episode of severe hypoglycemia (an episode necessitating third-party assistance).

About 25% have blunting of the symptoms of hypoglycemia — known as hypoglycemia unawareness — and such patients have a risk of severe hypoglycemia that is increased by a factor of up to 6.7-9 Hypoglycemia has been called the single greatest barrier to achieving and maintaining good glycemic control in patients with diabetes.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND EFFECT OF THERAPY

One reason for continued poor glycemic controlin patients with type 1 diabetes is the erratic absorption

and action of subcutaneously injected

insulin,10 which lead to unpredictable swings in

blood glucose concentrations, and those swings,

in themselves, are associated with elevated glycated

hemoglobin levels11 and hypoglycemia12,13 (Fig. 1).

It is likely that patients with high variability in glycemic levels maintain an elevated glycated hemoglobin level because they fear that hypoglycemia will occur more frequently or will be more severe if glycemic levels are reduced.

Another reason for continued poor glycemic control is that the dose of long-acting insulin analogues cannot be modulated after injection — for example, to provide greater insulin delivery from the previously injected depot in the prebreakfast hours, in order to counter the increase in blood glucose levels at that time of day

(“dawn phenomenon”).

At meals, errors in estimating the size and composition of the meal and in the timing and magnitude of the preprandial insulin dose can cause excessive hyperglycemia or late hypoglycemia. Adjustment of

the insulin dose to account for exercise is daunting

for many patients. The frequency of hypoglycemia

unawareness and the risk of subsequent

hypoglycemia are highest among patients who

have had hypoglycemia most frequently in the

past. Finally, nonadherence to recommended

therapy is a contributor to poor control in a substantial

number of patients.

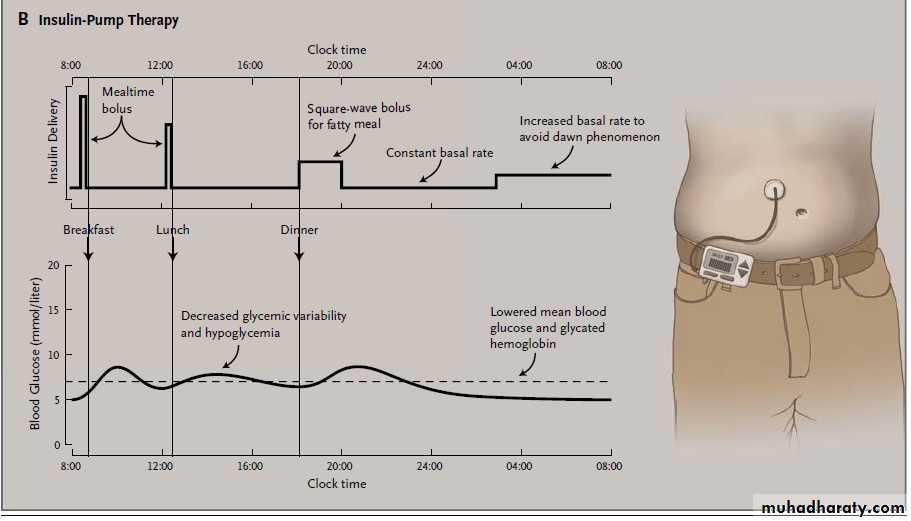

Insulin-pump therapy, or continuous subcutaneous

insulin infusion, was introduced more than

30 years ago as a procedure for improving

glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes

by mimicking the insulin-delivery patterns that

are present in persons without diabetes. A portable

pump infuses rapid-acting insulin at a slow

basal rate, 24 hours a day, through a fine cannula

implanted in the subcutaneous tissue, with

patient-activated insulin boosts (boluses) administered

at mealtimes (Fig. 1).

With insulin pumps in current use, the basal rate can either be altered on demand or preset to change at any time (e.g., during the night), and an onboard bolus

calculator can advise the patient regarding the

appropriate insulin dose at mealtime, as estimated

on the basis of carbohydrate intake, premeal and target blood glucose levels, insulin sensitivity,and a calculation of the insulin remaining since the previous bolus.18 Currently available pumps also have the capability for downloading data to a computer.

Insulin-pump therapy can improve glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes because it can reduce the within-day and between-day glycemic variability that is seen with insulin injections.

This effect may be related to the smaller subcutaneous depot of insulin during pump therapy (about 1 unit) and the low coefficient of variation for absorption during the basal-rate infusion — about ±3%, as compared with about ±50% for a large dose of injected isophane insulin. The reduction in glycemic

fluctuations allows patients to reduce glycated hemoglobin levels without increasing the risk of

hypoglycemia.

Insulin-pump therapy may also lessen the problems of glycemic control associated with injections because it allows for more flexible, preprogrammable basal insulin rates and extended-wave insulin profiles that can reduce the risk of hyperglycemia after fatty meals; because it includes a bolus calculator23; and because it includes the capability for computer downloads, which may identify control problems and aid in the adjustment of doses. In addition, one may

speculate that the increased flexibility of diabetes

management and the improved feeling of wellbeing

in patients who have an insulin pump may increase adherence to intensified therapy.

CLINICAL EVIDENCE

Several meta-analyses of randomized, controlledtrials of glycemic control with multiple daily insulin

injections as compared with insulin-pump therapy

have shown that mean glycated hemoglobin levels

are significantly lower with insulin-pump therapy

— with a mean difference of about 0.3 to 0.6%

between treatments — and this reduction in gly cated hemoglobin levels is accompanied by a 10 to20% reduction in the dose of insulin.

Among patients who switch from insulin injections to

insulin-pump therapy, the most important determinantof the benefit of pump therapy with respect

to glycemic control is the baseline glycated

hemoglobin level, with the greatest effect seen in

patients with the worst control at baseline.

For example, the expected mean decrease in the

glycated hemoglobin level is about 2 percentage

points when the baseline glycated hemoglobin is

10%, whereas it is 0 percentage points when the

baseline glycated hemoglobin is 7%.11

In a 2008 meta-analysis, the frequency of severe

hypoglycemia was compared among patients

receiving insulin-pump therapy and those

receiving multiple daily insulin injections; the

selected trials had a duration of 6 months or

more, were published between 1996 and 2006

(when monomeric insulin was used in the

pump), and included a study population that had

a high initial rate of severe hypoglycemia.

The meta-analysis showed that the frequency of severe

hypoglycemia was significantly higher with multiple daily insulin injections than with insulin-pump therapy (rate ratio, 4.19; 95% confidence interval, 2.86 to 6.13).28 The greatest reduction was seen among patients who had had the greatest number of episodes of severe hypoglycemia while they were receiving injection therapy. Among these patients, the rate of severe hypoglycemia was higher by a factor of about 30 with multiple daily insulin injections than withinsulin-pump therapy.

Several trials have also evaluated quality of life

among patients receiving insulin-pump therapy,with the use of a variety of measures. Although

the findings differ across trials and a metaanalysis

was not appropriate because of the use

of different scales, a Cochrane review concluded

that in many studies, pump therapy was preferred

over multiple-dose insulin injections with

respect to treatment satisfaction, quality of life,

and perception of general and mental health.

CLINICAL USE

Most people with type 1 diabetes can achieve acceptable control with multiple daily insulin injections when this therapeutic approach is applied sufficiently rigorously. It is therefore best to reserve the use of insulin-pump therapy for patients who have indications for which there is robust evidence for benefit (Table 1). In adults, these indications generally include poor control of hyperglycemia or disabling hypoglycemia, despite best efforts to achieve glycemic control with multiple daily insulin injections, although the specific criteria for these indications vary.

For example, the U.K. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends consideration of insulin-pump therapy for patients with persistent glycated hemoglobin levels of 8.5% or higher, whereas the Société Francophone du

Diabète uses a threshold of 7.5% or higher.

Although the same indications generally apply

to children, many pediatricians consider multipledaily insulin injections to be impractical or inappropriate for some children, because the children

may be unable or unwilling to inject insulin at

school and may need assistance from parents during

the day. Some experts therefore suggest that

children may be considered for pump therapy

without having first failed to have adequate glycemic

control with insulin injections.

Particular challenges in the treatment of adolescents, with respect to both multiple daily insulin injections and insulin-pump therapy, include nonadherence, insulin resistance, and changing activity and sleep patterns.

Though these variables are often managed

more effectively with pump therapy than with multiple daily insulin injections, some studies haveshown that teenagers are the population that is

most likely to have elevated glycated hemoglobin

levels while receiving insulin-pump therapy and

subsequently to discontinue the treatment.

Insulin-pump therapy may be used during

pregnancy. However, the consequences of

ketoacidosis during pregnancy (for example, if

pump failure were to occur) are of particular

concern. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to apply

the above criteria for initiating pump therapy to

pregnant women also, but with adjustment for the lower target levels of glycated hemoglobin

that are needed during pregnancy.

Insulin-pump therapy should be initiated by a

specialized hospital team comprising a physician,a diabetes nurse, and a dietitian trained in

pump procedures. Initiation of pump therapy by

primary care physicians is not recommended. It

is important for the patient to be willing and

motivated to use the insulin pump.

The necessary commitments include frequent self-monitoring of blood glucose levels (four to six times daily),

carbohydrate counting (adjustment of the insulin

dose according to the estimated amount of carbohydrate

in an intended meal), and working with the pump team to learn pump procedures.

Starting insulin-pump therapy is generally contraindicated when a clinical team that specializes

in this treatment is not available, when the patient

is unwilling or unable to use the pump, or

when the patient has major psychiatric problems.

Commercially available insulin pumps contain

a reservoir that holds about 200 to 300 units of

insulin, a battery with an effective life of several

weeks, and electronic controls for the operation

of the pump.

Pumps usually have a display screen and controls to allow the user to enter information on dose and time. Most pumps deliver insulin through a flexible plastic tube, typically 60 or 110 cm in length and terminating in a Teflon cannula or stainless-steel needle, which is inserted into the subcutaneous tissue. The cannula may be implanted manually or automatically with the use of a spring-loaded device.

One currently available pump is “tubeless,” with the cannula integrated into the pump and a hand-held controller that is used to adjust rates.

Other small “patch pumps” of this type, in which the pump is attached to the body with an adhesive patch (some including a remote-control device), are in development.

Monomeric, rapid-acting insulin analogues

(aspart, lispro, or glulisine) are now consideredto be the insulins of choice for pumps. For selecting

the initial basal rate, the total daily injected

dose is calculated and then is usually reduced

by 20%. The basal rate is then calculated

as 50% of that value; initially, only one rate is

used for the entire 24-hour period, with varying

rates introduced later. The overnight rate should

be adjusted to maintain the prebreakfast blood

glucose concentration in the target range.

Carbohydrate counting is used to determine the

bolus dose before a meal, which is based on

the carbohydrate content of the intended meal;

the patient’s insulin sensitivity at meals (“insulinto-

carbohydrate ratio”); and a correction dose that is based on the blood glucose level before the meal, how far that level deviates from the target blood glucose level, and the insulin sensitivity factor.

There are formulas that can be used to estimate the insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio (e.g., 500 ÷ total daily insulin dose = grams of carbohydrate for each unit of insulin) and the insulin sensitivity factor (100 ÷ total daily insulin dose = blood glucose lowering [in millimoles per liter] for each unit of insulin; this calculation is also used to correct unexplained hyperglycemia between meals).

When the blood glucose is expressed in milligrams per deciliter, the insulin sensitivity factor is calculated as 1800 ÷ total daily insulin dose. Many patients now use bolus calculators to estimate insulin doses before meals.

The anterior abdominal wall is the most common

infusion site; the outer thighs, arms, hips, and buttocks can be used but generally have slower insulin absorption.

Areas of broken skin, lipodystrophy, or scarring should be avoided.

The infusion cannula should be changed every 2 to3 days and rotated to a new anatomical site —

just as the site of insulin injections should be

varied — to avoid lipohypertrophy. Keeping the

same infusion set in place for longer than 3 days

is associated with deterioration in glycemic control

and an increased risk of infection at the site.

After an initial start-up phase of approximately

6 months, when clinic visits or contact with health care professionals may be more frequent,

most patients who are receiving insulinpump

therapy do not need to be followed in the

outpatient clinic more often than was necessary

when they were receiving multiple daily insulin

injections — approximately every 6 months.

When patients receiving insulin-pump therapy

are admitted to the hospital as inpatients foremergency or elective treatments and investigations,

most prefer to continue receiving pump

therapy; however, since the hospital staff may be

inexperienced with continuous subcutaneous insulin

infusion, advice from the local insulin-pump

team and adherence to specific insulin-pump

protocols are strongly recommended.

Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion is more expensive than multiple daily insulin injections:

insulin pumps cost about $5,000 to $7,000,

depending on the manufacturer and the country

of purchase, with additional costs (about $2,500

per year) for pump supplies (infusion sets, reservoirs,

and batteries) and for staff time and training.

Cost-effectiveness studies indicating that insulin-pump therapy may be considered to be cost-effective.

About 20% of patients who are receiving insulin-

pump therapy continue to have problematic

hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. Such patients

may have further improvement with the addition of continuous glucose monitoring.

For this approach, a needle-type or wire-type

glucose sensor is implanted subcutaneously and

replaced about every 5 to 7 days. The sensor

measures interstitial glucose concentrations on

a nearly continuous basis. Data are transmitted

wirelessly to a portable meter or (in the case of

some models) to an insulin pump for display of

glucose values and trends.

In consultation with the patient, insulinpump

therapy should be discontinued if there isno sustained improvement in glycated hemoglobin

levels or the frequency or severity of hypoglycemia,

if psychiatric or other contraindications

emerge after the initiation of pump treatment,

or, possibly, if the patient has recurrent skin

infections. In addition, pump therapy should, of

course, be discontinued if the patient wishes to

return to the regimen of multiple daily insulin

injections. However, at most centers the rate of

discontinuation is only about 5% or less.

ADVERSE EFFECTS

Because there is a smaller subcutaneous depot of

insulin at any time with the insulin pump, there

is a greater risk that ketoacidosis will develop

with insulin-pump therapy than with multiple

daily insulin injections if, for example, insulin

delivery is interrupted because of a pump malfunction

or insulin demand is increased because

of an intercurrent illness. However, in practice,

the frequency of ketoacidosis is similar with the

two treatments, probably because regular

self-monitoring of blood glucose levels and a

prompt response to hyperglycemia are key parts

of modern pump practice.

Among patients at experienced centers, the frequency of ketoacidosis can be lower with insulin-pump therapy than with multiple daily insulin injections. Localized skin infections at the infusion site occasionally occur with insulin-pump therapy, but they

are rarely serious. Current pumps are robust

and reliable, but malfunctions can still occur.

Patients and health care professionals need achecklist of possible reasons for unexplained hyperglycemia, with the list including problems with the cannula (kinked, blocked, or leaking cannula or failure of the cannula to prime after change), problems at the infusion site (infection, lipohypertrophy, dislodgment of the infusion set, or a set that has been left in place for longer

than 3 days), malfunction of the pump (low battery,

inactive insulin or insulin past the expiration date, or mechanical or electrical failure with alarms), and patient-associated issues (missed bolus, incorrect basal rates, overcorrection of hypoglycemia, illness, use of drugs such as steroids,or menstruation).

Similarly, a checklist for unexplained hypoglycemia may include incorrect bolus or basal rates, performance of exercise without consumption of extra carbohydrates or reduction of the bolus or basal rate, delayed effect

of exercise, target levels that are set too low,

consumption of alcohol, gastroparesis, and inadequate

self-monitoring of blood glucose levels.

Areas of Uncertainty

It is unclear to what extent structured diabeteseducation programs such as the Dose Adjustment

for Normal Eating (DAFNE) program48 and

more enthusiastic input from health care professionals

would lessen the proportion of patients

who have elevated glycated hemoglobin levels

and hypoglycemia while they are receiving insulin-

injection therapy and who are thus candidates

for insulin-pump therapy.

There are relatively few randomized, controlled trials of insulin-pump therapy as compared with multiple daily insulin injections of the long-acting analogue insulins glargine and detemir, and more research into these regimens as part of DAFNE-type programs

would be helpful.

The expansion of patient groups selected for insulin-pump therapy beyond those with grossly elevated glycated hemoglobin levels and frequent episodes of hypoglycemia is also the subject of debate. The enhanced quality of life noted by many patients who are receiving pump therapy includes improvements in lifestyle flexibility, energy, wellbeing, family relationships, and the ability to perform effectively and confidently at work.These aspects are not easily captured by osteffectiveness studies.

Poor quality of life is mentioned in some guidelines as a criterion for selection of insulin-pump therapy (see below), but it is likely that increasing attention will be paid in the coming years to lifestyle issues and personal preference as indications for pump therapy.

Guidelines

The NICE guidelines recommend insulin-pumptherapy for adults when, despite the best attempts

to achieve target blood glucose levels with multiple

daily insulin-injection therapy, disabling hypoglycemic episodes continue to occur or glycated

hemoglobin levels remain high (≥8.5%) and

for children younger than 12 years of age whenever

multiple daily insulin injections are considered

to be impractical or inappropriate.

The guidelines for insulin pumps from the American

Association of Diabetes Educators notably alsoinclude “frequent and unpredictable fluctuations

in blood glucose” and “patient perceptions that

diabetes management impedes the pursuit of personal

or professional goals” as criteria for starting

pump therapy, and other guidelines cite similar

indications. However, many consider these indications

to be inadequately defined and believe

that they should be used as criteria only if there

is strong evidence that they have been associated

with hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia.

Recommendations

The patient described in the vignette has been

unable to achieve acceptable glycemic control

with multiple daily insulin injections — despite

having recently attended a diabetes education

course — because of disabling, severe hypoglycemia.

The hypoglycemia is probably due in part to

unpredictable glycemic fluctuations, which have

also prevented the lowering of glycated hemoglobin

to target levels.

If, after undergoing an assessment at a specialized center and discussing the options with a team that is experienced in insulin-pump therapy, the patient is willing and able to undergo a trial of such therapy, this should be arranged. It is to be expected that the

frequency of severe hypoglycemia will be reduced

and glycated hemoglobin levels will be lowered

and that the patient’s quality of life will improve.

His body-mass index may also be reduced, since

there will be less need for him to eat in order to

avoid hypoglycemia, and improved control may

be attained with a lower dose of insulin.