د. حسين محمد جمعة

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنةالبورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2012

Oral Pharmacologic Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A ClinicalPractice Guideline From the American College of Physicians

Ann Intern Med. 2012

Diabetes mellitus is the seventh leading cause of death in the United States.

In addition, it is a leading causeof morbidity and leads to microvascular (retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy) and macrovascular (coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular disease) complications.

Good management of type 2 diabetes with pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies is important and includes patient education, evaluation for microvascular and macrovascular complications, treatment of glycemia, and minimization of cardiovascular and other long-term risks.

In the United States, 11 unique classes of drugs are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Among people diagnosed with diabetes, most will receive more than 1class of diabetes medication: 14% take both insulin and oral medication and 58% take oral medications only .

The purpose of this ACP guideline is to address the pharmacologic management of type 2 diabetes by comparing the effectiveness and safety of currently available oral pharmacologic treatment for type 2 diabetes. The target audience for this guideline

includes all clinicians, and the target patient population comprises all adults with type 2 diabetes. These recommendations are based on a systematic evidence review by Bennett and colleagues (4) and an evidence report sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (5).

The 2011 review expands on a 2007 AHRQ

evidence report ,which discussed mortality, microvascular and macrovascular outcomes, intermediate outcomes, and adverse effects for drugs available until 2006. The 2011 report focuses on head-to-head comparisons and includes direct comparisons for monotherapy and dualtherapy regimens. Combination therapies with more than 2 agents were not included in the review. The 2011 report also includes evidence for more recently approved diabetes medications and excludes data on -glucosidase inhibitors, such as acarbose.METHODS

The evidence report informing this guideline revieweddata for 11 FDA-approved, unique classes of drugs for the treatment of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes. This guideline is based on a systematic evidence review that addressed the following key questions:

Key question 1: In adults aged 18 years or older with

type 2 diabetes mellitus, what is the comparative effectiveness of these treatment options for the intermediate outcomes of glycemic control (in terms of hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c

]), weight, or lipids?

Key question 2: In adults aged 18 years or older with

type 2 diabetes mellitus, what is the comparative effectiveness of these treatment options in terms of the following long-term clinical outcomes: all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular morbidity (for example, myocardial infarction and stroke), retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy?Key question 3: In adults aged 18 years or older with

type 2 diabetes mellitus, what is the comparative safety of these treatment options in terms of the following adverse events and side effects: hypoglycemia, liver injury, congestive heart failure, severe lactic acidosis, cancer, severe allergic reactions, hip and nonhip fractures, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, macular edema or decreased vision, and gastrointestinal side effects?Key question 4: Do safety and effectiveness of these

treatment options differ across subgroups of adults with

type 2 diabetes, in particular for adults aged 65 years or older, in terms of mortality, hypoglycemia, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes?

The systematic evidence review was conducted by the

Johns Hopkins Evidence-based Practice Center. This review updates a 2007 systematic review on the same topic and focuses on head-to-head comparisons rather than placebo-controlled trials (6, 7). The literature search included studies identified by using MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials.The studies that were selected included observational studies and trials published in the English language from 1966 through April 2010.

In addition, the MEDLINE search was updated to December 2010 for long-term clinical outcomes (all-cause mortality, cardiovascular morbidity and

mortality, nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy).

Reference lists, FDA medical reviews, European Public Assessment Reports, Health Canada Product Monographs, unpublished data from pharmaceutical companies, and public registries of clinical trials were also reviewed.

Standardized forms were used for data abstraction, and each article underwent double review.

Quality of randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) was assessed by using the Jadad criteria, and quality of observational studies was assessed as

recommended in the Guide for Conducting Comparative Effectiveness Reviews .The statistic was used to determine study heterogeneity .Further details about the methods and inclusion and exclusion criteria applied in the evidence review are available in the full AHRQ report.

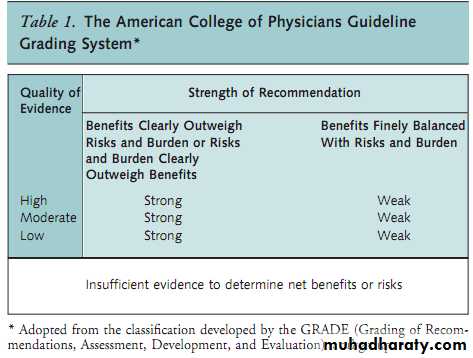

This guideline rates the recommendations by using the

American College of Physicians guideline grading system,which is based on the GRADE system (Table 1). Details of

the ACP guideline development process can be found in

ACP’s methods paper (11). This guideline focuses on results that were statistically significant, and details on non–statistically significant results are available in the full

AHRQ report.

COMPARATIVE EFFECTIVENESS OF TYPE 2 DIABETES

MEDICATIONS ON INTERMEDIATE OUTCOMES

Table 2 summarizes the key findings and strength of

evidence for intermediate outcomes comparing various diabetes medications as monotherapy or as combination

therapy.

HbA1c Levels

Evidence was gathered from 104 head-to-head RCTs

that varied from low to high quality and offered direct

evidence from comparisons among various type 2 diabetes medications

Monotherapy vs. Monotherapy

Most diabetes medications had similar efficacy and reduced HbA1c levels by an average of 1 percentage point (4). However, pooled results from 3 studies (reported in 4 papers) showed that metformin decreased HbA1c levels more than did dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors (mean difference, 0.37 percentage point [95% CI, 0.54 to 0.20 percentage point]; 0%; moderate quality evidence) DPP-4 inhibitor (mean difference, 0.69 percentage point [CI, 0.56 to 0.82 percentage point];Monotherapy vs. Combination Therapy

All dual-regimen combination therapies were more ef-ficacious than monotherapy and reduced HbA1c

levels by an average of 1 additional percentage point compared with monotherapy (4). Pooled data for the combination of metformin with another agent compared with metformin monotherapy showed a greater decrease in HbA1c levels:

metformin plus a sulfonylurea (mean difference, 1.00 percentage point [CI, 0.75 to 1.25 percentage point];

85%; high-quality evidence), metformin plus a

97%; moderatequality evidence), metformin plus a thiazolidinedione (mean difference, 0.66 percentage point [CI, 0.45 to 0.86 percentage point]; 84%; high-quality evidence).

Comparisons between different combinations of drugs

showed similar effects, although few trials were available.

Evidence from trials that included glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists was graded as insufficient or low Combination Therapy vs. Combination Therapy

One RCT showed that the combination of metformin

plus a GLP-1 agonist (liraglutide) statistically significantly decreased HbA1c levels by 0.34 to 0.60 percentage points in low- and high-dose combinations compared with metformin plus a DPP-4 inhibitor (sitagliptin) (low-quality evidence) (16). A post hoc analysis of a small RCT showed that the combination of a thiazolidinedione plus a sulfonylurea decreased HbA1c levels by 0.03 percentage point. (P 0.04) more than did the combination of metformin plus a thiazolidinedione (low-quality evidence) (17).

All other combinations had similar efficacy in reducing HbA1c levels.

Body WeightEvidence was gathered from 79 head-to-head RCTs

that varied from low to high quality and offered direct

evidence from comparisons among various type 2 diabetes medications.

Monotherapy vs. Monotherapy

Pooled results showed that monotherapy with metformin resulted in more weight loss compared with thiazolidinediones (mean difference, 2.6 kg [CI, 4.1 to 1.2 kg]; 85%; high-quality evidence) (18 –25), sulfonylureas (mean difference, 2.7 kg [CI, 3.5 to 1.9 kg];51%; high-quality evidence) (23, 26 –36), and DPP-4 inhibitors (mean difference, 1.4 kg [CI, 1.8 to 1.0; 5%; moderate-quality evidence) .Monotherapy with a thiazolidinedione compared with a sulfonylurea resulted in more weight loss (mean difference, 1.2 kg [CI, 0.6 to 1.9 kg]; 0%; low-quality evidence) (23, 37– 40). Compared with GLP-1 agonists, sulfonylureas showed more weight gain (mean difference, 2.5 kg [CI, 1.2 to 3.8 kg]; I

93%; moderate-quality evidence), although the studies were very heterogeneous (41– 43).

Monotherapy vs. Combination Therapy

Pooled data showed that metformin monotherapy wasmore effective in decreasing body weight than metformin

plus a thiazolidinedione (mean difference, 2.2 kg [CI,

2.6 to 1.9 kg]; 0%; high-quality evidence) (24,

44 – 47) or metformin plus a sulfonylurea (mean difference, 2.3 kg [CI, 3.3 to 1.2 kg];

83%; highquality evidence) (29 –36, 48, 49). Metformin was also favored when compared with metformin plus meglitinides in 2 RCTs (50, 51).

Combination Therapy vs. Combination Therapy

Pooled data showed that the combination of metformin plus a sulfonylurea was favored for weight compared with metformin plus a thiazolidinedione (mean difference, 0.9 kg [CI, 0.4 to 1.3 kg]; 0%; moderatequality evidence) (52–56). Pooled data also showed that the combination of metformin plus a sulfonylurea is favored over the combination of a thiazolidinedione and sulfonylurea (mean difference, 3.17 [CI, 5.21 to 1.13 kg]; 83%; moderate-quality evidence).

Compared with the combination of metformin plus a sulfonylurea (glipizide), metformin plus a DPP-4 inhibitor (sitagliptin) statistically significantly reduced weight in 1 RCT (mean difference, 2.5 kg [CI, 3.1 to 2.0 kg]) (57), and the trend continued when the study was extended for another year (mean difference, 2.3 kg [CI, 3.0 to 1.6 kg]) (low-quality evidence) (58). Combination of metformin plus a GLP-1 agonist also resulted in greater weight loss compared with the combination of metformin plus a sulfonylurea, as shown in 2 RCTs (low-quality evidence).

Plasma Lipid Levels

Evidence was gathered from 74 head-to-head RCTsthat varied from low to high quality and offered direct

evidence from comparisons among various type 2 diabetes medications. Most diabetes medications had a small to moderate effect on lipid levels: 5 to 10 mg/dL for low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, 3 to 5 mg/dL for high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and 10 to 30 mg/dL for triglycerides

LDL Cholesterol Levels

Monotherapy vs. Monotherapy.Monotherapy with metformin decreased LDL more than did thiazolidinedione monotherapy with pioglitazone (mean difference, 4.21mg/dL [CI, 15.29 to 13.13 mg/dL]; 0%; highquality evidence) (18, 22, 25, 60 – 62) or rosiglitazone(mean difference, 12.76 mg/dL [CI, 23.96 to 1.56

mg/dL]; 56%; moderate-quality evidence) .

Metformin was also favored over both sulfonylureas (mean difference, 10.1 mg/dL [CI, 13.3 to 7.0 mg/dL];

85%; high-quality evidence) and DPP-4 inhibitors (mean difference, 5.9 mg/dL [CI, 9.7 to 2.0 mg/dL];

28%; moderate-quality evidence) (12, 14, 15). Pooled data showed that monotherapy with sulfonylureas more effectively reduced LDL cholesterol than did pioglitazone (mean difference, 7.12 mg/dL [CI, 5.26 to 8.98 mg/dL]; 4%; low-quality evidence) (40, 68, 69), and 2 RCTs showed that rosiglitazone increased LDL cholesterol compared with sulfonylurea monotherapy (low-quality evidence) (37, 39).

Monotherapy vs. Combination Therapy.

Compared with metformin monotherapy, combination of metformin with other agents did not show any benefit (5).Combination Therapy vs. Combination Therapy. Thecombination of metformin plus a sulfonylurea was favored over metformin plus a thiazolidinedione, as pooled data showed for rosiglitazone (mean difference, 13.5 mg/dL [CI, 9.1 to 17.9 mg/dL]; 0%; moderate-quality evidence) (54, 55, 70, 71) and a single RCT showed for pioglitazone (mean difference, 8.5 mg/dL; P 0.03; lowquality evidence) (56).

The combination of metformin plus a sulfonylurea was also favored over the combination

of pioglitazone plus a sulfonylurea, as reported in 2 RCTs (low-quality evidence) (72, 73).

HDL Cholesterol Levels

Monotherapy vs. Monotherapy.Monotherapy with metformin was less effective than a thiazolidinedione (pioglitazone) at increasing HDL cholesterol levels (mean difference, 3.2 mg/dL [CI, 4.3 to 2.1 mg/dL]; 93%; high-quality evidence) (18, 22, 23, 25, 60 – 62, 74).Monotherapy with a thiazolidinedione more effectively increased HDL cholesterol levels compared with a sulfonylurea, as shown by pooled data for pioglitazone (mean difference, 4.27 mg/dL [CI, 1.93 to 6.61 mg/dL]; 99%;

moderate-quality evidence) and data from 2 RCTs for rosiglitazone (range in median between-group difference, 3.5 to 7.7 mg/dL; low-quality evidence) (37, 39). Two RCTs also showed that monotherapy with pioglitazone was favored over meglitinides (mean difference, 7 mg/dL; low-quality evidence) (75, 76).

When thiazolidinediones were compared, pioglitazone increased HDL cholesterol levels more than did rosiglitazone (mean difference, 2.33 mg/dL [CI, 3.46 to 1.20 mg/dL]; 0%; moderate-quality evidence) (77–79)

Monotherapy vs. Combination Therapy. The combination of metformin with a thiazolidinedione was better than monotherapy with metformin, as shown by pooled data for rosiglitazone (mean difference, 2.8 mg/dL [CI, 3.5 to 2.2 mg/dL];

83%; high-quality evidence) and 2 RCTs favored the combination of metformin plus pioglitazone over metformin monotherapy.

Combination Therapy vs. Combination Therapy.

The combination of metformin plus a thiazolidinedione was favored over the combination of metformin and a sulfonylurea, as shown by pooled data for rosiglitazone (mean difference, 2.7 mg/dL [CI, 1.4 to 4.1 mg/dL];0%; moderate-quality evidence) (54, 55, 70, 71), data from RCTs for pioglitazone (between-group differences ranged from 5.1 mg/dL [P 0.001] to 5.8 mg/dL [P 0.001]; low-quality evidence) (56, 84).

Post hoc analysis in 1 RCT showed that the combination of metformin plus pioglitazone increased HDL cholesterol levels (2.3 mg/dL; P 0.009) compared with pioglitazone plus sulfonylurea (0.4 mg/dL; P 0.62) (low-quality evidence) (84).

Three RCTs found an increase in HDL cholesterol levels with the combination of pioglitazone plus a sulfonylurea compared with metformin plus a sulfonylurea (low-quality evidence)

Triglyceride Levels

Monotherapy vs. Monotherapy. Metformin monotherapy decreased triglyceride levels compared with sulfonylureas (mean difference, 8.6 mg/dL [CI, 15.6 to 1.6 mg/dL]; 92%; moderate-quality evidence) and rosiglitazone (mean difference, 26.86 mg/dL [CI, 49.26 to 4.47 mg/dL]; 70%; moderate-quality evidence) . However, pooled data from other studies showed that pioglitazone decreased triglyceride levels more than did metformin (mean difference, 27.2 mg/dL [CI, 24.4 to 30.0 mg/dL]; 0%; high-quality evidence) and sulfonylureas (mean difference, 31.62mg/dL [CI, 49.15 to 14.10 mg/dL]; 91%; lowquality evidence) .Two RCTs also favor pioglitazone over meglitinides for reducing triglyceride levels

Monotherapy vs. Combination Therapy.

Metformin monotherapy decreased triglyceride levels more than metformin plus a thiazolidinedione (rosiglitazone) (mean difference, 14.5 mg/dL [CI, 15.8 to 13.3 mg/dL]; 0%; high-quality evidence).However, than with metformin monotherapy, combination therapy consisting of metformin plus a DPP-4 inhibitor (mean difference, 20.68 mg/dL [CI, 0.79 to 42.14

mg/dL]; low-quality evidence; P 0.05) or metformin plus meglitinides (data from a single RCT:

range of between-group differences, 17.8 to 8.9 mg/dL;

P 0.05 for the higher-dose nateglinide; low-quality evidence) (50) decreased triglyceride levels more than did metformin alone.

Combination Therapy vs. Combination Therapy. Two RCTs showed that the combination of metformin plus pioglitazone decreased triglyceride levels more than did metformin plus a sulfonylurea (between-group differences ranged from 10 mg/dL [P 0.30] to 24.9 mg/dL [P 0.045]; moderate-quality evidence) (56, 84). One small RCT found that metformin plus a GLP-1 agonist fared better than the combination of metformin plus rosiglitazone (between-group mean difference in triglyceride levels, 36.3 mg/dL; significance not reported; lowquality evidence) (86).

In addition, data from 4 RCTs showed that the combination of a thiazolidinedione (pioglitazone) plus a sulfonylurea decreased triglyceride levels

more or increased triglyceride levels less than the combination of metformin plus a sulfonylurea (low-quality evidence).

COMPARATIVE EFFECTIVENESS OF TYPE 2 DIABETES

MEDICATIONS ON LONG-TERM CLINICAL OUTCOMESA total of 66 studies (46 RCTs; duration, 12 weeks to

6 years) reported comparative effectiveness of oral diabetes medications on long-term outcomes. The mean age of participants ranged from 48 years to 75 years (5). It was difficult to draw conclusions about the comparative effectiveness of type 2 diabetes medications on all-cause mortality, cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, and microvascular

outcomes because of low quality or insufficient evidence

Mortality (All-Cause and Cardiovascular)

Five RCTs (30, 31, 33, 88, 89) and 11 observational

studies (90 –100) were examined for all-cause mortality between metformin monotherapy and sulfonylurea monotherapy. These studies indicate that metformin was associated with lower all-cause mortality compared withsulfonylureas (low-quality evidence). Metformin was also favored over sulfonylureas for cardiovascular mortality (low-quality evidence), as evidenced by ADOPT (A Diabetes Outcome Progression Trial) (89) and 4 cohort studies (92, 94, 96, 101), although 1 prospective cohort study showed a slightly higher cardiovascular mortality rate for

metformin than for sulfonylurea monotherapy.

Morbidity (Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular)

Monotherapy with metformin was linked to lower cardiovascular morbidity than combination therapy for metformin plus sulfonylureas (low-quality evidence), as shown by 1 RCT (5% vs. 14% adverse cardiovascular events) and 1 cohort study (adjusted incidence of hospitalization for myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization, 13.90 vs. 19.44 per 1000 person-years) (102). Evidence for all other comparisons was insufficient or unclear.Retinopathy, Nephropathy, and Neuropathy

There was moderate-quality evidence for nephropathy only for the comparison between pioglitazone and metformin. In the 2 studies that addressed this comparison, pioglitazone significantly reduced the urinary albumin–creatinine ratio by 19% (25) and 15% (72), whereas the ratio was unchanged in patients treated with metformin.COMPARATIVE SAFETY OF TYPE 2 DIABETES

MEDICATIONSAppendix Table 3 (available at www.annals.org) summarizes the findings and strength of evidence for adverse effects among various diabetes medications as monotherapy or combination therapy.

Hypoglycemia

No particular monotherapy or combination therapyincreased severe hypoglycemia (generally defined as hypoglycemia requiring assistance for resolution) compared with the other treatments.

Monotherapy vs. Monotherapy

Pooled results from monotherapy trials show that sulfonylureas increase the risk for mild to moderate hypoglycemia compared with metformin (odds ratio [OR], 4.60 [CI, 3.20 to 6.50]; 68%; high-quality evidence) ,thiazolidinediones (OR, 3.88 [CI,3.05 to 4.94]; 41%; high-quality evidence) (37– 40,

74, 89, 103–105), and meglitinides (OR, 0.78 [CI, 0.55 to 1.12]; 18%; low-quality evidence) (106 –113). Datafrom RCTs also indicate that other agents were favored over sulfonylureas for hypoglycemia:

DPP-4 inhibitors

(data from 1 RCT showed that 21 of 123 patients treated with a sulfonylurea had mild or moderate hypoglycemia compared with no patients treated with a DPP-4 inhibitor; and GLP-1 agonists

(data from 3 RCTs; high-quality evidence) (41– 43).

Monotherapy with meglitinides resulted in more hypoglycemia compared with metformin (OR, 3.00 [CI, 1.80 to 5.20]; 0%; moderate-quality evidence)

or thiazolidinediones (2 RCTs: relative risk [RR], 1.2 [CI, 0.8 to 1.8] [76]; RR, 1.6 [CI, 1.0 to 2.6] [119]; lowquality evidence).

Monotherapy vs. Combination Therapy

Compared with metformin monotherapy, the combination of metformin plus a thiazolidinedione (OR, 1.57[CI, 1.01 to 2.43]; 0%; moderate-quality evidence) ,metformin plus a sulfonylurea (RR, 1.6 to 25 in 9 RCTs; moderate-quality evidence), and metformin plus meglitinides (OR, 2.75 [CI, 0.98 to 7.71]; 21%; low-quality evidence; P 0.05) (49 –51) resulted in an increase in hypoglycemia.Combination Therapy vs. Combination Therapy

The combination of metformin plus a sulfonylureaincreased the risk for hypoglycemia by about 6 times compared with the combination of metformin plus a thiazolidinedione (OR, 5.80 [CI, 4.30 to 7.70]; 0%; highquality evidence) (17, 52, 54, 56, 71). One large RCT reported that metformin plus a thiazolidinedione resulted in fewer hypoglycemic events compared with a thiazolidinedione plus a sulfonylurea (0.05 vs. 0.47 event per 100 person-years of follow-up; low-quality evidence) .

Another study found more hypoglycemic symptoms in patients treated with the combination of metformin plus a sulfonylurea than with the combination of a thiazolidinedione plus a sulfonylurea (RR, 1.3 [CI, 0.9 to 2]; low-quality evidence) .

Other Adverse Effects Evidence was insufficient to show any difference among the various type 2 diabetes medications on liver injury.

Evidence from 51 studies was evaluated to determine

gastrointestinal effects (5). Evidence examined from studies addressing these effects that compared metformin monotherapy with thiazolidinediones (high-quality evidence) ,sulfonylureas (moderate-quality evidence) ,DPP-4 inhibitors (moderate-quality evidence) (12, 14, 15), or meglitinides

(low-quality evidence) (115–118) report more gastrointestinal adverse effects with metformin.

Trials comparing metformin monotherapy with combination metformin plus thiazolidinedione therapy (moderate-quality evidence)

or metformin plus sulfonylurea therapy (moderate-quality evidence) generally favored the combination therapy, although the metformin dosage was typically lower in the combination group, possibly accounting for this difference.

One RCT reported more dyspepsia with a combination of metformin plus a meglitinide than with metformin plus asulfonylurea (13% vs. 3%; low-quality evidence)

Two RCTs reported more diarrhea in combination treatment with metformin plus a sulfonylurea than with a thiazolidinedione plus a sulfonylurea (moderate-quality evidence) .

Although few studies reported on congestive heart failure, moderate-quality evidence from 5 observational studies favors metformin over sulfonylureas ,and moderate-quality evidence from 4 RCTs and 4 observational studies favors sulfonylureas over thiazolidinediones.

One 6-month observational study reported higher rates of heart failure with the combination of a thiazolidinedione plus a sulfonylurea (0.47 per 100 person-years) than with athiazolidinedione plus metformin (0.13 per 100 personyears) (low-quality evidence) One RCT reported that the combination of a thiazolidinedione plus a sulfonylurea or metformin doubled the risk for heart failure compared with a sulfonylurea plus metformin (RR, 2.1 [CI, 1.35 to 3.27]; low-quality evidence) (129).

Evidence was insufficient to show any difference

among the various type 2 diabetes medications on macular edema.

One RCT identified 1 person with cholecystitis out of

105 patients treated with a thiazolidinedione compared with none of 100 patients treated with metformin (lowquality evidence) (22). Another RCT identified 1 person with cholecystitis (n 280) treated with metformin monotherapy compared with no patients (n 288) treated with a combination of metformin plus a thiazolidinedione(low-quality evidence)

Low-quality evidence for pancreatitis came from 1 trial that reported 1 patient (n 242) with acute pancreatitis treated with a combination of metformin plus a sulfonylurea compared with no patients

receiving metformin monotherapy (n 121) (49). The

evidence was insufficient to show any difference in cholecystitis or pancreatitis with other monotherapies or combination therapies.

For bone fractures, high-quality evidence from 1 RCT

showed more bone fractures with thiazolidinedione monotherapy than with metformin monotherapy (hazard ratio [HR], 1.57 [CI, 1.13 to 2.17]), and subgroup analysis showed that the risk is higher for women (HR, 1.81 [CI, 1.17 to 2.80]; P 0.008) (130).

Data were assessed from 2 RCTs and 1 observational study, and results showed fewer fractures with sulfonylureas than with thiazolidinediones (high-quality evidence) (38, 130, 131). One RCT found an increase in fractures for patients treated with

rosiglitazone compared with a sulfonylurea (HR, 2.13 [CI,1.30 to 3.51]) (130), whereas another study reported 2 ankle fractures (n 251) with pioglitazone monotherapy and no fractures with sulfonylurea monotherapy (n 251) (38). The observational study found statistically significantly more fractures in women treated with pioglitazone (HR, 1.70 [CI, 1.30 to 2.23]; P 0.001) and rosiglitazone (HR, 1.29 [CI, 1.04 to 1.59]; P 0.02) than with sulfonylurea (131).

The combination of metformin plus asulfonylurea was favored over the combination of thiazolidinediones plus a sulfonylurea or thiazolidinediones plus metformin (RR, 1.57 [CI, 1.26 to 1.97]; P 0.001; highquality evidence), and the RR for fractures was higher for

women than men (1.82 [CI, 1.37 to 2.41] vs. 1.23 [CI,

0.85 to 1.77]) (129).

COMPARATIVE EFFECTIVENESS OF TYPE 2 DIABETES

MEDICATIONS ACROSS SUBGROUPS OF ADULTS AGED 65 YEARS OR OLDER

Evidence was gathered from 28 studies (21 RCTs) that

reported comparative effectiveness and safety data for subpopulations (defined by age, sex, or race; obesity, duration of diabetes, or geographic region; required medication dose; previous comorbid conditions) (5). The evidence favoring one medication over another across subgroups is not clear because of lack of sufficient power in the included studies.

SUMMARY

The evidence shows that most diabetes medicationsreduced HbA1c levels to a similar degree. Metformin was more effective than other medications as monotherapy as well as when used in combination therapy with another agent for reducing HbA1c

levels, body weight, and plasma lipid levels (in most cases). It was difficult to draw conclusions about the comparative effectiveness of type 2 diabetes

medications on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular morbidity, and microvascular outcomes because of low-quality or insufficient evidence.

heart failure, and both rosiglitazone and pioglitazone are contraindicated in patients with serious heart failure.

The current evidence was not sufficient to show any

difference in effectiveness among various medications

across subgroups of adults.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 1: ACP recommends that clinicians

add oral pharmacologic therapy in patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes when lifestyle modifications, including diet, exercise, and weight loss, have failed to adequately improve hyperglycemia (Grade: strong recommendation; high-quality evidence).

High-quality evidence shows that the risk for hypoglycemia with sulfonylureas exceeds the risk with metformin or thiazolidinediones and that the combination of metformin plus sulfonylureas is associated with 6 times more risk for hypoglycemia than the combination of metformin plus thiazolidinediones. Moderate-quality evidence shows that the risk for hypoglycemia with metformin and thiazolidinediones is similar. Metformin is associated with an increased risk for gastrointestinal side effects. Thiazolidinediones are associated with an increased risk for Initiation of oral pharmacologic therapy is an important approach to effective management of type 2 diabetes.

There are no data on the best time to add oral therapies to lifestyle modifications; thus, to avoid an unacceptable burden on patients, other complicating factors should be considered, such as life expectancy of the patient, presence or absence of microvascular and macrovascular complications, risk for adverse events related to glucose control, and patient preferences (134). The goal for HbA1c should be based on individualized assessment of risk for complications from diabetes, comorbidity, life expectancy, and patient preferences. An HbA1c level less than 7% based on individualized assessment is a reasonable goal for many but not all patients.

Recommendation 2: ACP recommends that clinicians

prescribe monotherapy with metformin for initial pharmacologic therapy to treat most patients with type 2 diabetes (Grade: strong recommendation; high-quality evidence). The effectiveness, adverse effect profiles, and costs of various oral pharmacologic treatments vary. Metformin is more effective than other pharmacologicagents in reducing glycemic levels and is not associated

with weight gain. In addition, metformin aids in decreasing weight and reduces LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels. Metformin was also associated with

slightly lower all-cause mortality and cardiovascular

mortality compared with sulfonylureas.

Finally, metformin is associated with fewer hypoglycemic episodes and is cheaper than most other pharmacologic agents.

Therefore, unless contraindicated, metformin is the

drug of choice for patients with type 2 diabetes, in addition to lifestyle modification. Metformin is contraindicated in patients with impaired kidney function, decreased tissue perfusion or hemodynamic instability, liver disease, alcohol abuse, heart failure, and any condition that might lead to lactic acidosis.

Physicians and patients should discuss adverse event

profiles before selecting a medication. Compared withbaseline values, most diabetes medications (metformin,

thiazolidinediones, and sulfonylureas) reduced baseline

HbA1c by about 1 percentage point 3 or more months after the initiation of treatment.

For adverse effects, metformin is associated with an increased risk for gastrointestinal side effects, sulfonylureas and meglitinides are associated with an increased risk for hypoglycemia, and thiazolidinediones are associated with an increased risk for heart failure (with no conclusive evidence for an increase in ischemic cardiovascular risk). However, in comparing the effectiveness of various agents, the evidence shows that metformin is the most efficacious agent as monotherapy and in combination therapy.

Recommendation 3: ACP recommends that clinicians

add a second agent to metformin to treat patients with persistent hyperglycemia when lifestyle modifications and monotherapy with metformin fail to control hyperglycemia (Grade:

strong recommendation; high-quality evidence).

All dual-therapy regimens were more efficacious than

monotherapies in reducing the HbA1c

level in patients with type 2 diabetes by about 1 additional percentage point.

Combination therapies with more than 2 agents

were not included in the evidence review. No good evidence supports one combination therapy over another, even though some evidence shows that the combination of metformin with another agent generally tends to have better efficacy than any other monotherapy or combination therapy.However, combination therapies are also associated with an increased risk for adverse effects compared

with monotherapy.

Generic sulfonylureas are the cheapest second-line therapy; however, adverse effects are generally worse with combination therapies that include a

sulfonylurea.

Although this guideline addresses only oral pharmacological therapy, patients with persistent hyperglycemia despite oral agents and lifestyle interventions may need insulin therapy.

See Figure 1 for a summary of the recommendations

and clinical considerations.

ACP BEST PRACTICE ADVICE

On the basis of the evidence reviewed in this paper,ACP has found strong evidence that in most patients

with type 2 diabetes in whom lifestyle modifications

have failed to adequately improve hyperglycemia, oral pharmacologic therapy with metformin (unless contraindicated) is an effective management strategy. It is cheaper than most other pharmacologic agents, has

better effectiveness, and is associated with fewer adverse effects; of note, it does not result in weight gain (Figure 2).