FDA approves first drug to prevent HIV infection

BMJ 17 July 2012)د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2012

The US Food and Drug Administration this week approved for

the first time a drug for use in the prevention of HIV infection.The drug, Truvada, is one of the most commonly used

components of an anti-HIV “cocktail” regimen in the United

States and Europe.

Truvada is two drugs combined in a single pill, tenofovir

disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine. Its preventive use is

commonly referred to as PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis).

Studies in different groups at high risk of infection have shown

its efficacy.

It was approved “to reduce the risk of HIV infection in

uninfected individuals who are at high risk of HIV infection

and who may engage in sexual activity with HIV-infected

partners,” said Debra Birnkrant in a telephone press conference

with reporters. She is director of the Office of Antimicrobial

Products at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

Although the incidence of HIV in the US has held steady for

about a decade, at about 50 000 new infections a year, it has

increased in some groups, notably young men from ethnic

minority groups who have sex with men, she said. “

These data show that treatment and new prevention methods are needed in order to have a major impact on the HIV epidemic in this country.”

She added, “Truvada for PrEP represents another effective, evidence based approach that can be added to other prevention methods to help reduce the spread of HIV . . . [when] used daily

as part of a comprehensive HIV prevention strategy that includes other prevention measures.”

After concerns discussed at an advisory committee meeting in May, the FDA has added a “black box warning” to the label requiring that “a negative HIV test must be documented before

prescribing the drug and throughout use of PrEP.”

The FDA’s risk evaluation and mediation strategy requires counsellor education and training for those who prescribe PrEP.

Patients will be given educational materials and urged to sign “a contract” to be placed in their file stating that they understand the need for strict adherence to the daily regimen and for quarterly testing for HIV.

Some people fear that PrEP might lead to “disinhibition” and hence greater risk of infection because of riskier sex and less condom use. Birnkrant said that the placebo controlled studies

did not support that fear.

Furthermore, she said, there is reason

to believe that adherence might increase in real world use because people know that they are being prescribed a drug whose effectiveness has been proved.

The drug has been widely used for a decade and is generally well tolerated. There are some long term problems of bone and kidney toxicity that are “for the most part manageable, can be monitored,” and are reversed on discontinuation of treatment, said Birnkrant.

Support for PrEP has been widespread but not universal among

those working in HIV prevention and treatment. One vocalopponent has been the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, a large

provider of HIV care that is based in Los Angeles but that has

clinics in several states and internationally.

“Widespread use of PrEP has all the makings of a public health

disaster: increased HIV infections, drug resistant strains of HIV,

and tens of thousands of damaged kidneys,” said the

foundation’s president, Michael Weinstein, in March, when it

filed a “citizens’ petition” with the FDA to delay or deny

approval of the drug for prevention.

Gilead Sciences, which makes the drug, has said that it will

work with public health officials and community groups to makesure that the drug is available to those who need it most. This

is likely to include price discounts.

There are no estimates of how widespread use of PrEP might

become. Leading health insurance companies have stated that

they will cover the cost of the drug for a PrEP indication once

it is approved.

No Link Between Birth Defects and Antiretroviral Use in Pregnancy

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) Jul 19 - Antiretroviral use in pregnancy does not seem to increase the risk of birth defects, a new U.S. study finds.

Lead author Dr. Robert S. Brown Jr from the New York Presbyterian Hospital told Reuters Health by email, "It is reassuring" that pregnant women can take tenofovir or lamivudine and "there does not appear to be any increase in the birth defects."

"The data provide guidance for patients and practitioners who either need or want to begin these drugs in pregnancy as to their predicted safety," he said.

Antiretrovirals are not licensed for use in chronic hepatitis B in pregnancy, and their safety is not fully established, but Dr. Brown and his coauthors point out that the drugs are still sometimes used to reduce viral load and mother-child transmission.

"The purpose of this study is not to advocate off-label use of antiviral therapies in pregnancy," they said.

Using data on 13,711 women registered with the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry (APR) from 1989-2011, the researchers analyzed birth defect rates among users of various antiretrovirals. Major structural defects, chromosomal defects diagnosed by age six, and aborted fetuses were all counted as birth defects.The authors say the APR is the largest worldwide registry of birth defects related to exposures to antiviral drugs.The prevalence of birth defects was similar among the antiretroviral users and population-based controls (2.8% vs. 2.7% respectively), the researchers reported online June 26th in the Journal of Hepatology.

Birth defect rates were also similar with antiretroviral exposure in the first trimester and later trimesters (3% vs. 2.7%).

Rates with lamivudine, tenofovir and all antiretrovirals combined were similar as well: 3.1%, 2.4% and 3%, respectively, during first trimester and 2.7%, 2% and 2.8% during later trimesters.

The authors say they specifically looked for an increased risk of cardiovascular and renal defects with lamivudine and did not find it.

"The fact that initial exposure to these medications in the first, versus remaining, trimesters was associated with similar birth defect rates supports a lack of teratogenicity,"

Dr. Brown and his colleagues wrote.

"Safety is a complex term and (it is) obviously better to not need to take any medications during pregnancy," Dr. Brown said. "But this (study) suggests that any adverse effects on the fetus are rare enough that they cannot be detected in this relatively large data set."Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention

NEJM July 18, 2012c ase vignet tes

The first patient, a 46-year-old sexually active

man who has sex with men, presents for routine

primary care. He lives in New York City and reports

that he is in a long-term, stable, open relationship

with a male partner and that he has had

multiple recent sexual encounters with acquaintances.

A recent HIV test was negative. He has seasonal allergies, for which he occasionally takes antihistamines, and chronic lower back

pain, for which he takes nonsteroidal antiinflammatory

drugs on a regular basis. Otherwise he takes no medications and has no known allergies to medications. He had syphilis 10 years earlier for which he was successfully treated. His physical examination is notable only for the fact that he is uncircumcised.

You review HIV prevention strategies in detail with him, including the potential benefits of circumcision and of the use of condoms. He has been reading information on the Internet, including information about preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and asks whether he should be receiving this therapy.

The second patient, an 18-year-old heterosexual

woman in South Africa who has recently becomesexually active, presents for voluntary HIV testing.

She does not know the HIV status of her male

partners. She reports no medical problems, is taking

no medications, and has no known allergies

to medications. She reports that her older sister

recently received a diagnosis of HIV infection.

Her physical examination is unremarkable.

Testing for sexually transmitted infections is performed.

A pregnancy test is negative. She would like to

initiate birth control and elects to start taking

oral contraceptive pills. She returns to the clinic

the following week and is informed that all the

tests for sexually transmitted infections, including

the HIV test, were negative. She thinks that

she had received the hepatitis B vaccination series.

She is negative for hepatitis B surface antigen. She

is given extensive HIV counseling, and the various

HIV prevention strategies are reviewed in detail.

Which one of the following approaches would

you find appropriate for these patients? Baseyour choice on the published literature, your own

experience, recent guidelines, and other sources

of information, as appropriate.

1. Recommend initiating PrEP.

2. Do not recommend initiating PrEP.

To aid in your decision making, each of these

approaches is defended in the following short

essays by experts in the prevention of HIV infection.

Recommend Initiating PrEP

Salim S. Abdool Karim, M.B., Ch.B., Ph.D.

The decision-making process for recommending

PrEP begins with an assessment of the risk of

HIV, followed by a determination of the combination

of HIV-prevention strategies that provides

the maximum protection. In the United States,

men who have sex with men comprise approximately

2% of the population but account for

more than 60% of new HIV infections.

Treatment option 1

A history of sexually transmitted diseases and multiple

partners places the man in the first vignette athigh risk. Despite education and condom-promotion

programs, young women are the highest risk group in Africa, where the prevalence of

HIV among women 20 years of age is as high as

26.7%.1 The fact that the young woman in the

second vignette has had multiple partners places

her at high risk in the generalized HIV epidemic

in South Africa, where 12% of the population

(approximately 5.6 million people) are HIV-infected.

Her risk is higher if any partner is 5 or more

years older than she is.

The effective options for HIV prevention that

are available for the persons in both vignettes include the use of condoms, “sero-sorting” (choosing only partners who are HIV-negative), treatment for prevention (ensuring that all HIV-positive partners are taking antiretroviral treatment),

and, finally, PrEP. Although medical circumcision

of men is an established HIV-prevention option

for heterosexual men, it has not yet been

proven to be effective in protecting women or

men who have sex with men

Although an HIVprevention strategy that is based on knowing every partner’s HIV status is desirable, this is rarely possible. Even partners who recently tested HIV-negative have a tangible risk, in highincidence groups, of having an undiagnosed

“window-period” infection or of having acquired

HIV after the test was performed.

Among HIVpositive partners who say they are receiving treatment, the risk of their transmitting the virus to others depends on their having actually

initiated treatment, their adherence to treatment,

and consequent viral suppression. In the case of

young African women, who are seldom able to

insist on the use of condoms or to establish the

HIV status or treatment status of their partners,

placing their risk of infection totally in the

hands of their male partners is risky and fundamentally undermines efforts to empower women to control their own risk.

Hence, PrEP, which empowers receptive partners

to control their HIV risk, is an essential

component of an effective combination prevention

strategy for the persons in both vignettes.

In the absence of renal disease, daily treatment

with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) coformulated

with emtricitabine (FTC), a therapy for

which there are extensive safety data, should be

prescribed, since it was shown to be effective in

reducing HIV acquisition among men who have

sex with men in the Preexposure Prophylaxis

Initiative (iPrEX) trial4 and among heterosexual

partners in the Partners PrEP5 and TDF26 trials.

In these studies, drug resistance, which is aconcern with the use of any antiretroviral agent,was an uncommon occurrence and was largelyrestricted to persons who initiated PrEP during an undiagnosed window-period infection. Nucleic acid testing (which tests for the presence of virus before antibodies can be detected) at the time of the initiation of PrEP, a costly option,

could reduce the risk of resistance.

For resistance that may still be present at the initiation of future treatment, effective therapeutic options

other than TDF–FTC are available. It is important

that PrEP be accompanied by counseling on

the continued and increased use of condoms and

on adherence to therapy, in order to avoid the

lack of effectiveness that was observed in the Preexposure Prophylaxis Trial for HIV Prevention

among African Women (FEM-PrEP).

Widespread implementation of PrEP is, however,

not without challenges that will require additional

financial resources and health services

capacity. Nevertheless, PrEP is an essential new

HIV-prevention strategy that can and should be

implemented in combination with the use of condoms, HIV testing, and promotion of treatments

for HIV infection. PrEP prevents HIV infection,

thereby reducing the need for treatment of AIDS

in the future, is cost-effective,8 and empowers

vulnerable populations to directly control their

risk of HIV infection.

Do Not Recommend Initiating

PrEPGlenda E. Gray, M.B., B.Ch., and

Neil Martinson, M.B., B.Ch., M.P.H.

There are an estimated 5.6 million HIV-infected

people in South Africa, and countrywide surveillance

of pregnant women shows that 14.0% of

pregnant girls and women 15 to 19 years of age

and 26.7% of pregnant women 20 to 24 years of

age were HIV-infected in 20109 — statistics that

suggest that the woman in the second vignette is

at high risk for HIV infection.

treatment option 2

PrEP with daily TDF–FTC4 has been shown to

reduce the risk of HIV acquisition in two specific

populations — men who have sex with men

and serodiscordant couples in Africa. However,

the data are inconclusive, since other trials have

shown no effect in women. PrEP was not shown

to be effective in the FEM-PrEP study,7 in which

daily TDF–FTC was administered in women, nor

in the TDF group of the Vaginal and Oral Interventions

to Control the Epidemic (VOICE) study,10

which was discontinued early for futility.

Although adherence to daily medication has been shown

to influence the effectiveness of PrEP, the inconsistentresults among similar PrEP studies suggest that additional factors influence the effectiveness of PrEP in preventing the acquisition of HIV.

The efficacy data reported from the Partners PrEP study are difficult to extrapolate to the general population, since there may be unique features associated with HIV transmission in the context of a long-term, stable, serodiscordant partnership.

The data on the efficacy of PrEP in the TDF2 study, which was conducted in Botswana, are tantalizing, but there are substantial challenges to understanding these data, especially the effect of the low rate of retention of participants

(which resulted in early termination of the study),

the poor adherence to the study medication, and

an apparent benefit only early after the initiation

of PrEP.

At first glance, the reported 62.2% reduction in HIV acquisition is compelling; however, of nine participants who were HIV-infected despite the receipt of TDF–FTC, seven were women, and in a subanalysis that was restricted

to women, there was no significant protection with TDF–FTC as compared with placebo. Moreover, this and other studies raise concerns about the interaction of TDF–FTC with oral contraceptives, the selection of viral resistance in persons

with undetected HIV-infection at baseline and in

those who undergo seroconversion while receiving

PrEP, and the proper monitoring over time

of the safety of PrEP, including the effect on renal

function and bone mineral density.

Given the high risk of inducing HIV resistance at the initiation of PrEP, HIV nucleic acid testing (not just HIV

antibody testing) should be considered as part of

the assessment before the initiation of PrEP. This

testing is costly and not widely available. The

implications of all these issues in the context of

the increased clinical use of PrEP are substantial

and have yet to be pragmatically sorted out.

Our management of the cases described in both vignettes would therefore include HIV testing

and counseling, including encouragement

that the partners be tested for HIV. We would

encourage the woman in the second vignette to

approach her partners (who are assumed to be

heterosexual, HIV-negative, and uncircumcised)

to be circumcised. We would provide an adequate

supply of male and female condoms and

highlight the importance of adherence to oral

contraceptives.

Given the available data, recommending initiation

of PrEP is premature in either circumstance.

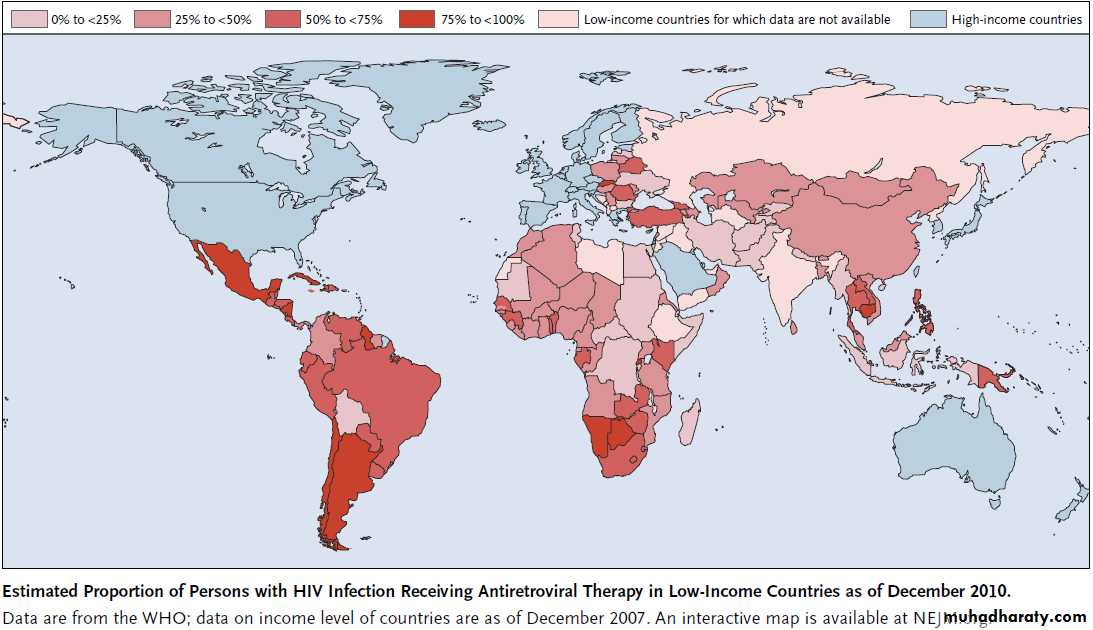

For example, in South Africa, approximately 1.8

million people have initiated antiretroviral therapy,

representing 55% of the people who require

this therapy. First-line therapy now includes TDF,

at a cost of $11 billion (in U.S. dollars).

The implementation of antiretroviral therapy in South

Africa has been further stressed by the increasein the threshold for initiating treatment to a CD4

count of 350 cells per cubic millimeter. In addition,

the frequent lack of availability of antiretroviral

drugs suggests that existing antiretroviral

treatment programs are already overwhelmed.

Until robust concordant trial data are available

to guide the complexity of practice here, we

should not grasp at straws. Giving effective antiretroviral

treatment to HIV-infected persons earlier

and enhancing the use of proven strategies

should be the current mainstays for preventing

HIV transmission.

In neonates whose mothers did not receive ART during pregnancy, prophylaxis with a

two- or three-drug ART regimen is superior to zidovudine alone for the prevention of

intrapartum HIV transmission; the two-drug regimen has less toxicity than the threedrug

regimen. (Funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health

and Human Development [NICHD] and others; ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00099359.)

NEJM June 20, 2012.

The Beginning of the End of AIDS?

NEJM July 18, 2012.We are at a moment of extraordinary optimism

in the response to the human immunodeficiencyvirus (HIV). A series of scientific breakthroughs,

including several trials showing the partial efficacy of oral and topical chemoprophylaxis and the first evidence of efficacy for an HIV vaccine candidate,

have the potential to markedly expand the available preventive tools.

There is evidence of the first cure of an HIV-infected person. And most important, the finding that early initiation of antiretroviral therapy can both improve

individual patient outcomes and reduce the risk of HIV transmission to sexual partners by 96%4 has led many to assert what had so long seemed impossible:

that control of the HIV pandemic may be achievable.

What will it take to achieve what U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton called, in a2011 address, an “AIDS-free generation”?

Expanded access to and coverage of high-quality prevention and treatment services tailored

to affected populations are critical to keeping people living with HIV healthy and to dramatically

reducing the number of new HIV infections.

This goal requires an ambitious implementation science agenda that improves efficiency and effectiveness and incorporates strategies for overcoming the stigma and discrimination

that continue to limit the uptake and utilization of services.

Research efforts on HIV vaccines will also probably be key, and thefield has been reinvigorated, after

a series of unsuccessful trials, by the findings of the RV144 trial involving Thai adults, which showed that the vaccine provided modest protection against HIV acquisition in selected populations.

Research focused on curing HIV disease is yielding fascinating insights into how HIV persists in the

face of current therapy, and such research must be earnestly pursued. A combination approach to

prevention that includes HIV treatment can generate tremendous gains in the short term by curtailing

new HIV infections, but ending the AIDS epidemic will

probably require a vaccine, a cure, or both.

The scientific opportunities and optimism at this moment in HIV research are not matched, however, by the available resources.

Global resources have been declining, not growing, in this period of scientific success. This lack of funding is the major point of divergence between optimism and pessimism.

Every country, including ours, must develop more effective ways to reach key affected populations

and to apply the tools that we know work, if we are to make significant advances.

Is there a roadmap to an AIDSfree generation? The core elements of a strategy are arguably now

in hand: first, the strategic use of existing resources, including resources for accelerated research

on prevention, HIV vaccines, and a cure; second, marked increases in HIV testing, counseling, and

linkages to and retention in services and care;

third, the eradication of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and preservation of maternal health, a goal very much within the realm of possibility with existing knowledge; and finally, expanded access to prevention services and antiretroviral treatment to reach everyone in need — which will require an end to the stigma, discrimination,

legal sanctions, and human rights abuses against people at risk for or living with HIV infection.

Markedly expanding high-quality treatment programs, taking newprevention tools to scale, and

maximizing the potential of antiretroviral therapies for prevention will be difficult and costly, but failure to capitalize on the scientific advances of this critical period could be devastating. A future of ongoing transmission of HIV,ever-increasing numbers of people receiving or needing therapy, and further strains on overburdened health systems will not be sustainable.

As the international HIV community gathers in Washington, D.C., for the 19th International AIDS Conference, the meeting’s theme, “Turning the Tide Together,” captures the essence of this defining moment. The response to HIV, perhaps better than efforts against any other epidemic, encapsulates

what can be accomplished when scientists, policymakers, the private sector, and the community mobilize toward a common goal. Propelling us to the point where we can talk about the end of AIDS is nothing short of remarkable.Yet the most important part of the story is about to be written.