White and Brown adipose tissue

2012د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2012

Brown fat

Metabolically highly active adipose tissue, which is involved in heat production to maintain body temperature, as opposed towhite adipose tissue, which is storage fat and has a low rate of metabolic activity.

Definition of brown fat :A thermogenic form of adipose tissue found in newborns of many species, including humans, and in hibernating mammals. The tissue is capable of rapid liberation of energy and seems to be important in the maintenance of body temperature immediately after birth and upon waking from hibernation.Brown adipose tissue

A layer of special heat-producing fat cells found mainly around the shoulder blades and kidneys; it is more abundant in infants than adults.Brown fat cells contain many more mitochondria than other types of fat cells. Mitochondria are sometimes called the powerhouses of the cell because they are the organelles responsible for aerobic respiration. They usually produce the energy-rich storage compound ATP, but in brown fat their activity is diverted to heat production.

The colour of brown fat is derived from highly pigmented chemicals (cytochromes) contained within the mitochondria.

These cytochromes enable mitochondria to produce heat instead of ATP.

The purpose of brown fat in small mammals and babies is to maintain body temperature. Hibernating mammals metabolize brown fat to re-warm their bodies during arousal. Brown fat is well supplied with blood which can transport the heat to different parts of the body. Unlike other types of fat, it has its own nerve supply which can quickly stimulate it to produce heat when the animal (or baby) gets cold.

There has been a lot of speculation about the significance of brown fat in adults. It makes up less than 1 per cent of the body weight and is generally regarded as unimportant. It is, however, more abundant in lean than in fat animals and some researchers believe that it plays a role in regulating body weight and energy balance, at least in small mammals. It has also been shown that some forms of obesity and overweight in mice are linked to an inherited lack of brown fat.

Some members of the slimming industry have capitalized on these ideas by marketing special clothes with holes in the back and arm pits, which they claim will stimulate the formation of brown fat and help you lose weight effortlessly. The effectiveness of these clothes has yet to be scientifically proven.

White adipose tissue (WAT) or white fat

In humans, white adipose tissue composes as much as 20% of the body weight in men and 25% of the body weight in women. Its cells contain a single large fat droplet, which forces the nucleus to be squeezed into a thin rim at the periphery. They have receptors for insulin, growth hormones, norepinephrine and glucocorticoids.White adipose tissue is used as a store of energy. Upon release of insulin from the pancreas, white adipose cells' insulin receptors cause a dephosphorylation cascade that lead to the inactivation of hormone-sensitive lipase. Upon release of glucagon from the pancreas, glucagon receptors cause a phosphorylation cascade that activates hormone-sensitive lipase, causing the breakdown of the stored fat to fatty acids, which are exported into the blood and bound to albumin, and glycerol, which is exported into the blood freely.

Fatty acids are taken up by muscle and cardiac tissue as a fuel source, and glycerol is taken up by the liver for gluconeogenesis.

White adipose tissue also acts as a thermal insulator, helping to maintain body temperature.

In Biology, adipose tissue or body fat or fat depot or just fat is loose connective tissue composed of adipocytes. It is technically composed of roughly only 80% fat; fat in its solitary state exists in the liver and muscles. Adipose tissue is derived from lipoblasts. Its main role is to store energy in the form of lipids, although it also cushions and insulates the body. Far from hormonally inert, adipose tissue has in recent years been recognized as a major endocrine organ,as it produces hormones such as leptin, resistin, and the cytokine TNFα.

Moreover, adipose tissue can affect other organ systems of the body and may lead to disease. Obesity or being overweight in humans and most animals does not depend on body weight but on the amount of body fat. The formation of adipose tissue appears to be controlled in part by the adipose gene.

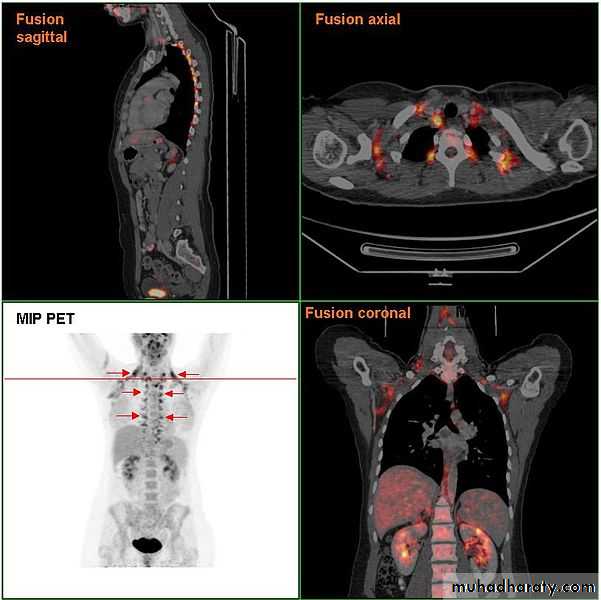

File:Brownf at PETCT.jpg

BAT was believed to show rapid involution in early childhood, leaving only vestigial amounts in adults. However, recent evidence suggests that its expression in adults is far more common than previously appreciated, with a higher likelihood of detection in women and leaner individuals.It is conceivable that BAT activity might reduce the risk of developing obesity since fat stores are used for thermogenesis, and a directed enhancement of adipocyte metabolism might have value in weight reduction.

These observations support an important influence of the endocrine system on BAT activity and offer new potential targets in the treatment of obesity.

Brown adipose tissue (BAT), in contrast to white adipose tissue (WAT), is involved in energy dissipation rather than storage, but was previously considered to have little physiological relevance in humans beyond early childhood. However, recent studies using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET–CT) prove that BAT is present in adults, with activity notably declining with increasing obesity.

Working within the context of clinical endocrinology, the authors ask could the recruitment of larger amounts of BAT or an enhancement of its activity be an 'antidote' to obesity?

Obesity is the product of a mismatch in energy supply and utilization, resulting in the deposition of WAT. In humans, this is almost inevitably because of a combination of excessive dietary intake and too little exercise. Interestingly, excision or denervation of BAT in animal models leads to an abnormal increase in WAT, implying a significant impact upon energy balance.

Energy Balance and Thermogenesis

The primary function of BAT is in the generation of heat. Thermogenic mechanisms are customarily classified as either obligatory or facultative. Obligatory thermogenesis (OT) represents the energy dissipated as heat in the many energetic transformations inherent in life and equates to basal metabolic rate at thermoneutrality.

In a cold environment, facultative thermogenesis (FT) may be required to maintain core temperature. Initially, heat is produced by shivering, which is replaced as acclimatization proceeds with nonshivering mechanisms in which BAT activation plays a key role.

The ultimate phenotype of any cell is determined by the sequential activation of a cascade of transcription factors during differentiation. Those which drive the formation of WAT and BAT must inevitably activate expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), indispensable for adipogenesis.

BAT Structure and Function

Whilst both WAT and BAT are derived from mesenchymal stem cells, perhaps unsurprisingly, they appear to have distinct lineages, with Myf5 (shared with skeletal myocyte progenitors), PGC-1α[6] and PRDM16[7] (PR-domain-containing 16) expression, distinguishing the brown from white adipocyte precursors .

BAT and WAT adipocytes differ widely in morphology (summarized in Table 1), reflecting their different functional roles. Mitochondria are present in high numbers in brown adipocytes, particularly in comparison with white adipocytes, and are central to BAT activity. The mitochondria release chemical energy in the form of heat by means of uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation, making the process of respiration inefficient.

It is not intended to review the process in detail here, but in brief this phenomenon is mediated by uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), which renders the inner membrane of the mitochondria 'leaky', and hence releases energy in the form of heat rather than storing it as ATP. UCP1 is in turn regulated by triiodothyronine (T3), possibly through the β-subunit of the thyroid hormone receptor, which is generated within BAT by the action of type 2 deiodinase (D2) on thyroxine (T4), effectively creating a local, tissue-specific hyperthyroid state in the absence of changes in circulating thyroid hormones.

Sympathetic stimulation, via the β3-adrenergic receptor (found almost exclusively in adipose tissue in rodents), enhances thermogenesis; the precise mechanism by which this is achieved remains unclear, however.

Whilst both BAT and WAT, as would be expected, have neuroanatomically well-characterized sympathetic innervation (with activation initiating thermogenesis and lipid mobilization, respectively), there is little evidence to support the presence of a putatively counter-regulatory parasympathetic input.[8] Previous studies have however hinted indirectly at such, atropine, a nonspecific muscarinic receptor (MR) antagonist, has been shown to enhance the thermogenic response in rats,[9]

although the authors' failed to demonstrate the presence of any markers of parasympathetic innervation at that time. Interestingly, despite a lack of evidence to support this counter-regulatory role for the parasympathetic nervous system, M3 MR knockout mice weigh significantly less (22%) than wild-type, attributable to a marked reduction in visceral WAT;[10] no indication of BAT status was provided.

In most mammals, BAT is found predominantly in anatomically discrete depots, classically the interscapular region and axillae (for review, see Cannon & Nedergaard[11]). However, BAT can emerge in animal WAT depots in response to cold or prolonged β-adrenergic stimulation, but the mechanism remains unclear. Certainly, brown adipocytes have been identified histologically in up to 50% of younger patients, seeded amongst white adipocytes,[12] whilst based on UCP1 mRNA quantification,[13] there would appear to be approximately one brown adipocyte per 100–200 white adipocytes within human visceral WAT.

Thus, the observed increase in BAT may be because of simple clonal expansion and maturation of an already present population of committed preadipocytes. However, it has been recently reported that rat epididymal WAT adipocytes chronically exposed to the thiazolidinedione (TZD) rosiglitazone (a PPARγ agonist) share BAT-type characteristics, but do not express the transcription factors (most notably PRDM16) associated with BAT.[14]

These appear to be the so-called brite (brown-in-white) cells, which have BAT characteristics, but do not seem to have the same lineage. This report suggests that these brite cells arise from trans-differentiation. The possibility of a pharmacologically driven switch from WAT to BAT is highly attractive in the context of the clinical management of obesity.

Is There Functional BAT in Humans?

Or, perhaps more specifically, is there functional BAT in adults? Whilst present in significant quantities in the neonate,[15] until recently, it was assumed that rapid involution in the first years of life left only vestigial amounts of BAT in healthy human adults. Physiologically, the requirement for nonshivering thermogenesis is limited by our other adaptations to environment (clothing and heating), although a study nearly 30 years ago showed at least one group of outdoor workers in Scandinavia to have increased BAT deposits.

Whilst information about normal tissue function can often be gleaned from pathological states, this also proved to be of limited value for BAT. Brown fat tumours (or hibernomas, from their resemblance to adipose tissue in hibernating animals[17]) are rare, benign and seemingly asymptomatic; though, significant weight loss has been associated with the tumour in at least one case report.[18]

Interestingly, β3-adrenoreceptor polymorphisms leading to a reduction in receptor function (notably the substitution of a tryptophan to an arginine residue at position 64) have been linked to weight gain,[19] as well as being positively associated with early-onset type 2 diabetes

Circumstantial evidence for BAT activity came from the experience of those interpreting PET–CT scans (see Fig. 2). The radiotracer 18F-FDG follows glucose metabolism initially, but does not enter the Krebs cycle after phosphorylation, and is therefore trapped within the cell. 18

F-FDG-PET simply monitors glucose uptake, with highly metabolically active tissues being labelled; what this actually means can, of course, only be inferred.

It was noted that there was confounding high symmetrical uptake in regions previously found consistent with postmortem locations of BAT and that the intensity of these signals could be reduced by increasing the ambient temperature or by β-blockade.

In the first half of 2009, five independent groups used 18F-FDG-PET to identify and characterize BAT in adult humans (see Table 2 for summary). In a retrospective analysis of 3640 consecutive scans from 1972 patients, Cypess et al. [2] found putative BAT deposits in 7·5% of women and 3·1% of men, located mainly in the cervical, supraclavicular, axillary and paravertebral regions (echoing the sites in the neonate).

As well as being present in more than twice as many women, the deposits were also larger and showed greater levels of 18F-FDG uptake in female compared to male subjects. Probability of detection was inversely associated with age of subject, body mass index (BMI), β-blocker use and outdoor temperature at the time of the scan.

Confirming the importance of temperature on BAT activity, Van Marken Lichtenbelt et al. [21] demonstrated increased metabolic activity in (putative) BAT predominantly in the neck and supraclavicular region of 23 of 24 young, healthy male subjects when exposed to mild cooling.

Activity showed high intersubject variability. Mean activity was significantly lower in overweight or obese (BMI > 25) subjects. Interestingly, the single subject in whom there was no demonstrable 18F-FDG uptake also had the highest BMI (38·7). Virtanen et al. [22] reported a 15-fold increase in 18F-FDG uptake under similar conditions, but were also able to confirm the presence of BAT in these regions by demonstrating the presence of UCP1 mRNA and protein in biopsies from three of their five subjects. In addition, they showed the expression of D2 and the β3-adrenergic receptor, further indicating the potential for function.

This potential was supported by the demonstration of distinct islands of BAT in the necks of approximately one-third of a group of 35 patients undergoing thyroid surgery by Zingaretti et al. [23] The islands were highly vascular, with a rich sympathetic innervation, and demonstrated the presence of brown adipocyte precursors.

Whilst also confirming the inverse relationship between suprascapular and paraspinal 18F-FDG uptake and both total and visceral adiposity in their group of 56 healthy volunteers in response to acute cold, Saito and co-workers[24] demonstrated a degree of seasonal variability to their findings, with increased uptake during the winter months.

It would be reasonable to conclude that cold-inducible BAT is present in adults, with the largest depots in and around the neck. Observed in leaner individuals, and inversely associated with other indices of the metabolic syndrome, it may be implied that increasing BAT mass or activity offers a degree of protection from obesity. This is particularly so in the light of the relatively limited amounts of such tissue that would be required to make significant impact on energy balance; it has been estimated that as little as 50 g of BAT would account for 20% of daily energy expenditure.[25]

Based upon the registered rate of 18F-FDG uptake and data from substrate preference in rodents,[26] Virtanen and co-workers[22] speculated that the estimated 63 g of BAT found in the supraclavicular/paracervical depot of one of the subjects could combust the energy equivalent of 4·1 kg of WAT over 1 year. Before consideration of the therapeutic possibilities of this phenomenon, it may be of value to consider BAT in the context of wider endocrine function and disease in both animal models and humans.

BAT and Phaeochromocytomas

In the light of the key role of adrenergic stimulation in thermogenesis, one might predict significant expansion of BAT in patients with catecholamine-producing phaeochromocytomas. An association with brown fat tumours was noted nearly 40 years ago,[27] whilst Lean and co-workers[15] demonstrated the presence of BAT histologically, not present in controls, following laparotomy in three patients with phaeochromocytomas.Enhanced 18F-FDG uptake, which disappeared following surgical resection, has been reported in a patient with an extra-adrenal phaeochromocytoma,[28] emphasizing the effect of excess circulating catecholamines in enhancing BAT activity; interestingly, Hadi et al. [29] have demonstrated that the likelihood of identifying BAT in this patient group on PET–CT is increased at higher plasma noradrenaline levels.

BAT and Thyroid Status

A recent case report from Skarulis et al. [30] appears to link BAT activity and volume with circulating thyroid hormone levels. Classically of course, thyroid over- or underactivity gives rise to distinct phenotypes, reflecting the contrasting effects of hormone excess or deficiency on metabolism, body mass and composition. Thus, thyrotoxic individuals are heat intolerant and lean with reduced body fat, whilst hypothyroidism is associated with sensitivity to low ambient temperatures and weight gain.Hypothyroidism because of thyroid-stimulating hormone resistance is associated with an inability to maintain core temperature when exposed to cold in a mouse model (hyt/hyt) lacking a functional thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor; this can be reversed by gene transfer into BAT.[31] Conversely, as with phaeochromocytomas, some of the clinical features of hyperthyroidism could conceivably be explained in terms of an increased activation of BAT-dependent FT, but in this instance owing to excess circulating T3.

Previously, it had been argued that the requirement for a concomitant β3-adrenergic activation was against this; sympathetic stimulation of BAT had been described as being inversely related to thyroid status and thus reduced in the presence of excess systemic thyroid hormones (reviewed in Silva[32]). In addition, high concentrations of T4 themselves were shown to powerfully inhibit D2 activity.[33] Thus, it was felt that a generalized enhancement of metabolism, and thus increase in OT such as seen in skeletal muscle,[34] was the basis of the development of the hyperthyroid phenotype, rather than an upregulation of BAT activity.

However, Lopez et al. [35] (2010) have recently suggested that elevated T3 levels do indeed activate BAT, but indirectly via action at the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMH). They demonstrated that high levels of circulating thyroid hormones, or central administration of T3, were associated with enhanced neuronal activation and β3-adrenergic signalling, a shift in the ratio of BAT to WAT within fat pads, and increased BAT UCP1, PPARγ and D2 expression in rats.

The key process appears to be a reduction in the activity of hypothalamic adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase. This leads to changes in lipid metabolism within the VMH, although it is not yet clear how this and the observed increased activity of nerves innervating BAT are related.

It should be noted that no direct measure of BAT activity was used (enhancement implied by increased expression of thermogenic markers) nor any assessment of metabolic rate made (which would help to address the impact of OT in this context). Though one should always be cautious when extrapolating from animal models, a similar mechanism may operate in humans, and would certainly be compatible with the observations reported by Skarulis and co-workers.[30] This case appears somewhat atypical however, exhibiting significant confounding features.

BAT changes were observed in a clinically euthyroid patient receiving supraphysiological doses of thyroxine to suppress thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels on a background of papillary thyroid carcinoma and insulin resistance secondary to insulin receptor mutation. Although there was an overall reduction in weight and an improvement in glycaemic control with thyroxine treatment, there was no change in relative fat mass, whilst the contribution of obligate thermogenic mechanisms was only partially addressed. There is no evidence to support the therapeutic use of T3 to stimulate thermogenesis in obese individuals.

Whether BAT activation is or is not directly responsible for some of the signs and symptoms of thyroid disease, one still might predict there to be an association between the relative levels of circulating thyroid hormones (which exhibit a relatively wide 'normal range' in clinically euthyroid individuals) and degree of obesity (as a surrogate marker of BAT volume). As well as its autocrine effect on UCP1 production, there is a net release of T3 from BAT into the circulation.[36] This can be of considerable physiological significance; in rodents, for example, it has been suggested that BAT may be responsible for about half of the total systemic conversion of T4 to T3.[37

] BAT deposits in humans might be expected to behave similarly. Intriguingly, Shon et al. [38] have recently reported a negative correlation between plasma-free T4 levels and BMI in a large (1572) female cohort. Unfortunately, only T4 is discussed, although De Pergoli et al. [39] had previously shown free T3 levels to be positively associated with both BMI and waist circumference in a similar, though, smaller (201 women) experimental group.

In addition, they reported TSH levels to also be positively associated with waist circumference, in agreement with the observations of Iacobellis et al. [40] Shon and co-workers[38] failed to show any such associations for TSH. These observations may be interpreted as showing an enhanced T3 generation leading to relative T4 depletion and thus increased TSH signalling.

As this occurs in the context of increasing obesity, enhanced BAT D2 activation is an unlikely source of this excess T3 production. Interestingly, bolus leptin has been reported to increase type 1 deiodinase (D1) activity in both the thyroid and liver of euthyroid rats;[41] it may be speculated that the chronically increased plasma concentrations observed in obese individuals could have a comparable effect and thus underlie the observed variation in thyroid hormone levels.

BAT and Corticosteroids

Clinically, corticosteroid excess (Cushing's syndrome) is associated with obesity, primarily owing to an increase in visceral adipose tissue.[42] In animal models, this is driven by an expansion of WAT, which appears to be more sensitive to corticosteroids than BAT.[43]Both WAT and BAT express functional glucocorticoid receptors.[44] Interestingly, the reported effects of corticosteroids on BAT would be consistent with a reciprocal down-regulation of brown adipocyte activity. Thus, noradrenaline-induced UCP1 mRNA accumulation in a BAT cell line has been shown to be reduced by both an endogenous and synthetic corticosteroid,[45] whilst excess steroid increases the number and size of lipid droplets in brown adipocytes in a dose-dependent manner.[43]

An inhibitory effect on β3-adrenoreceptor expression in vitro has also been reported, although this appears to be only transient in vivo, despite continued exposure to corticosteroids.[46] Ashizawa and co-workers[47] demonstrated that the plasma levels of both leptin and adiponectin changed predictably as obesity improved following adrenalectomy in a patient with Cushing's syndrome.

This may simply correlate to the observed loss of mass from WAT deposits, rather than any direct causal relationship. Conversely, Addison's disease (corticosteroid deficiency) may have only a limited effect on BAT; Berthiaume and co-workers reported adrenalectomy to have no effect on BAT mass in rats, despite a marked reduction in visceral WAT.[48]

BAT and the Sex Hormones

The sex hormones have a marked effect on BAT activity. Receptor expression differs between BAT of male and female origin, with higher numbers of all receptor types in male brown adipocytes.[49] Rodriguez et al. [50] reported that cultured brown adipocytes, when exposed to testosterone, had fewer, smaller lipid droplets than untreated cells and expressed lower levels of UCP1 mRNA in response to adrenergic stimulation; a concomitant reduction in PGC1α transcription has also been described.[51]

The precise mechanism by which testosterone down-regulates BAT activity remains unclear, although it induces increased expression of the antilipolytic α2A-adrenoreceptor in brown adipocytes.[52]

As perhaps might be predicted, the female sex hormones appear to enhance BAT function. Certainly, oestrogen deficiency has long been noted to reduce thermogenic capacity in rats following ovariectomy,[53] associated with a reduction in BAT UCP1 levels.[54] The reported effects of the oestrogens and progesterone on brown adipocytes often overlap, but not invariably so; thus, whilst both promote the formation of larger, more numerous lipid droplets, only progesterone is noted to increase UCP1 mRNA levels.[50]

The female hormones (predominantly progesterone) also influence adrenergic stimulation of BAT by modulating the numbers of cell surface receptors, down-regulating (in contrast to testosterone) α2A- and up-regulating β3-adrenoreceptors[52] (although the affinity of the latter for noradrenaline may simultaneously be reduced[55]). In an additional boost to BAT activity, the female sex hormones also appear to positively influence mitochondrial production and recruitment.[51]

It is possible that it is not only the sex hormones themselves that effect BAT activity. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), a sex hormone precursor usually present in plasma in its sulphated form, is directly able to inhibit proliferation of a human brown adipocyte cell line,[56] perhaps as a necessary preliminary to differentiation. Supplementation in obese rats (which are relatively deficient in DHEAS) increases PGC1α, UCP1 and β3-adrenoreceptor expression; though, this was not seen in similarly treated lean rats.[57]

The different effects of the male and female sex hormones on adipose tissue may thus have a significant impact on phenotype, whether this be the gender-specific distribution of WAT (predominantly visceral in males and subcutaneous in females[58]) or the increased incidence of functional BAT in females described in the recent 18F-FDG-PET studies.

Is Therapeutic Manipulation of BAT Possible?

Although championed on occasion as having potential as an antiobesity organ,[72] the assumption that BAT was present only in neonates limited the appeal of any such approach. However, the recent demonstrations of significant deposits of adult BAT reviewed earlier have once again raised the possibility of their therapeutic manipulation to promote weight reduction (for review, see Fruhbeck et al. [73]).Although increased energy expenditure does not necessarily guarantee weight loss (just as a low basal metabolic rate does not necessarily lead to obesity[74]), it is precisely this, via an enhancement of FT, which is the ultimate goal of any BAT-orientated strategy to combat obesity in humans.

There are a series of complementary facets that might contribute to any successful intervention; thus, one might aim to stimulate the activity of already existing BAT, whilst favouring the recruitment of the few brown adipocytes in WAT or promoting the emergence of new BAT depots.

As might be expected, this is not entirely straightforward using traditional pharmacological approaches, owing to the lack of suitable pharmaceutical agents, and problems with unwanted additional effects. Take, for example, the use of adrenergic agents. Whilst β3-adrenergic stimulation is required to activate thermogenesis, proliferatively competent brown adipocytes express β1- rather than β3-receptors.

Exogenous β1 stimulation is thus required to increase cell numbers; this, unfortunately, brings with it unacceptable consequences on cardiac function. Similarly, the promising action of the TZD compounds has to be balanced against the possibly increased risk of cardiac and bone side effects. Although this remains controversial, the use of rosiglitazone is already proscribed.

Rimonabant has similarly been withdrawn in Europe owing to an increased risk of serious psychiatric side effects. Retinoic acid induces UCP1 expression in both BAT and WAT,[75] but has a wide range of other effects in vivo, limiting utilization.

If the use of pharmaceutical agents is currently challenging, the induction of specific gene expression to enhance BAT levels and activity has some merit. It has been demonstrated that enhancement of UCP1 levels by direct overexpression produces mice that are resistant to genetic- or diet-induced obesity (reviewed in Kozak & Koza[76]); the loss of inhibitors of UCP uncoupling activity [such as Cidea (cell death-inducing DFF45-like effector A)][77] produces similar results.

The overexpression of FOXC2 (a winged helix transcription factor) exclusively in adipocytes forces the shift from WAT to BAT in transgenic mice[78] as β3-adrenergic receptors are upregulated and cAMP levels increased. The inhibition of RIP140, a nuclear corepressor, shows similar promise. Known to repress UCP1 expression, RIP140-null adipocytes exhibit increased levels of UCP1 mRNA.

Initially, the authors asked whether recruitment of larger amounts of BAT or an enhancement of its activity could be an 'antidote' to obesity – perhaps, it is now more pertinent to ask whether this is actually practically possible. Whilst a pharmaceutical approach is clearly preferable economically, the lack of readily available candidates precludes this currently.

In most cases, even where genetic approaches show promise, they tend to remain primarily research tools rather than progressing to therapies; the treatment of obesity is potentially so lucrative that it may prove to be an exception

Conclusions

As the problems presented by obesity and its associated morbidities continue to grow, it appears that, paradoxically, adipose tissue itself may provide a solution. The adipose organ is not homogeneous, but comprises of two major tissue types of distinctive structure, function and lineage, as evidenced by their differing gene expression profiles; thus, BAT resembles muscle, but WAT is akin to macrophages.White adipose tissue performs the task most readily associated with adipose tissue, that of energy storage (though in a less passive fashion than had, perhaps, been believed previously), whilst the function of BAT is to protect body temperature in response to environmental cooling, generating heat by inefficient mitochondrial metabolism.

Whilst these two types are well preserved in most animals, BAT had been thought to be restricted to neonates only in man. Whilst, as a benefit of progress, man has acquired other means to keep himself warm, this has come with a relative abundance of food, a consistently positive energy balance, and thus endemic obesity. Obesity management is fraught with difficulties ranging from the limited range and inadequacy of therapeutic options to poor patient adherence with lifestyle changes.

The recent demonstrations of significant deposits of functional adult human BAT suggest another approach, namely the manipulation of facultative thermogenesis as an aid to weight loss. Whilst increasing both brown adipose tissue volume and activity is theoretically feasible (and is seen pathologically, on occasion), there are still many practical issues that require attention. It is however safe to say that we live in exciting times, particularly if that last diet just did not work!

• Waist-to-hip ratio

• Waist measured around the narrowest point between ribs and hips when viewed from the front after exhaling (usually around the belly-button or just above it).

• Measure hips at the widest part around buttocks when viewed from the side.

•

acceptable

unacceptableexcellent

goodaverage

high

extreme

male

< 0.85

0.85 - 0.90

0.90 - 0.95

0.95 - 1.00

> 1.00

female

< 0.75

0.75 - 0.80

0.80 - 0.85

0.85 - 0.90

> 0.90