Malignancy

د. حسين محمد جمعهاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2011

May 5, 2011 —

Radical prostatectomy appears to be a wise choice for men with early-stage prostate cancer who are younger than 65 years, according to new data from a Swedish randomized clinical trial that compares surgery with "watchful waiting."The study shows that, at 15 years, the cumulative incidence of death from prostate cancer was 14.6% among 347 men randomized to prostatectomy and 20.7% among 348 men being observed without treatment.

'Very, Very Important Paper' on Prostate Cancer Surveillance Longest-Running Trial of Watchful Waiting

However, the survival benefit was confined to men younger than 65 years of age, according to the study authors, led by Anna Bill-Axelson, MD PhD, from the University Hospital in Uppsala, Sweden.

For men older than 65 years, survival was highly similar in the 2 groups.

It has been conducted in men with predominantly symptom-detected early prostate cancer. All the men had clinical stage T1 or T2 disease, well or moderately well differentiated histologic findings, and a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of below 50 ng/mL.

"This is the best information we have to date on the extent to which treatment will influence outcomes in men with early prostate cancer," said H. Ballentine Carter, MD, from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. Dr. Carter was not involved with the study and was approached for comment by Medscape Medical News.

However, the results do not rule out the value of watchful waiting or active surveillance, said Dr. Carter.

"The study strongly supports the role of treatment and the role of surveillance," he said.

The results from this study indicate that a patient's age — and related life expectancy — are apparently pivotal to receiving benefit from watchful waiting in early prostate cancer, Dr. Carter explained.He interpreted the study findings for clinicians and patients.

"If you are young and have a long life expectancy — 15 years or more — then you need to be treated for prostate cancer," he said, adding that this even applies to men with very-low- or low-risk prostate cancer.

"If you are an older man — 65 to 70 years old — and you have low- or very-low-risk disease, your first consideration should be whether or not treatment is necessary," he pointed out. Such men should "consider being monitored."

Dr. Carter described the randomized controlled trial as a "very, very important paper," saying it was "very carefully done" research.

The fact that Dr. Carter advocates for possible surveillance among certain older men is in keeping with what he knows from his own experience.

He is the senior author of a recently published study of 769 men enrolled initially in active surveillance in which there have been no known prostate-cancer-specific deaths after an average follow-up of about 3 years.

"This study offers the most conclusive evidence to date that active surveillance may be the preferred option for the vast majority of older men diagnosed with a very low-grade or small-volume form of prostate cancer," he said about his study.

Men With Low-Risk Disease Also Benefited From Treatment

SPCG-4 enrolled men from 1989 to 1999; they now have a median follow-up of 12.8 years, which allowed the authors to make 15-year estimates.The study authors had previously shown that radical prostatectomy provided a survival benefit as well as a reduction in the risk for metastases (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1144-1154). The updated data continue to show these benefits, but over a longer period of time.

The "most important new finding" from SPCG-4 is that a subgroup of men with low-risk disease received a survival benefit from radical prostatectomy, said Matthew Smith, MD, PhD, in an editorial accompanying the study. Dr. Smith is a radiation oncologist at the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston.

Low risk was defined as a PSA level of less than 10 ng/mL and a tumor with a Gleason score of less than 7 or a World Health Organization grade of 1 in the preoperative biopsy specimens. There were a total of 124 men in the radical-prostatectomy group and 139 in the watchful-waiting group who qualified as low risk.

With respect to death from prostate cancer among these low-risk men, the absolute between-group difference at 15 years was 4.2% points (6.8% for the radical-prostatectomy group vs 11.0% for the watchful-waiting group).

This corresponds to a relative risk of 0.53 (95% confidence interval, 0.24 to 1.14; P = .14), according to the authors.This survival benefit for the low-risk men who received surgery might, however, not be "relevant" for many men who have low-risk prostate cancer detected today, Dr. Smith points out.

That is because most of the men in SPCG-4 had cancers detected on the basis of symptoms rather than by elevated PSA levels.

To illustrate what differences can arise out of these varying methods of detection, Dr. Smith notes that, in SPCG-4, the number needed to treat with prostatectomy to prevent 1 death at 15 years was 15. "The predicted number needed to treat is substantially greater for contemporary men with low-risk prostate cancers detected by PSA screening because the rates of death from prostate cancer are lower in this group," he writes.

Surgery Benefit Only in Younger Men: Novelty Questioned

The study authors say that their finding that only younger men benefited from surgery is novel in the literature. "The finding that the effect of radical prostatectomy is modified by age has not been confirmed in other studies of radical prostatectomy or external-beam radiation" they point out.They suspect that, contrary to their findings to date, surgery might have some survival benefit for some older men.

"The apparent lack of effect in men older than 65 years of age should be interpreted with caution because, owing to a lack of power, the subgroup analyses may falsely dismiss differences," they write.

The data have hints that surgery has a positive effect in at least some older men, they say.

"At 15 years, there was a trend toward a difference between the 2 groups in the development of metastases," they write about the watchful-waiting and surgery groups.

The study stipulated that men treated with surgery who progressed should receive hormonal therapy (as opposed to observed men who progressed — they received surgery). That might have allowed some men to die from other diseases, say the authors. "Therefore, competing risks of death may blur the long-term effects of treatment," they write.

2 years of rituximab maintenance therapy after immunochemotherapy as first-line treatment for follicular lymphoma significantly improves progression-free survival (PFS) .

The Lancet 21 December 2010

The Science and Art of Prostate Cancer Screening

Despite the clinical availability of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening for nearly a quarter of a century, there are still differences of opinion as to whether such screening is worthwhile. In an attempt to directly address this controversy, early results from two large randomized trials were published in 2009 .

• © The Author 2011. Published by Oxford University Press.

The European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) was a combined analysis of prospective randomized European trials consisting of a total of 162 243 subjects aged 55–69 years who were screened or observed at intervals up to 4 years and recommended for biopsies when the PSA levels were elevated (primarily ≥3.0 ng/mL) (1).

The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening (PLCO) study enrolled 76 693 men aged 55–74 years but screened them on an annual basis and recommended biopsies for PSA levels greater than 4.0 ng/mL (2). The ERSPC study showed a 20% relative reduction in prostate cancer mortality (rate ratio = 0.80, 95% confidence interval = 0.65 to 0.98, P = .04) (1) in the screened group, whereas the PLCO study did not show any statistically significant change in prostate cancer mortality (rate ratio = 1.13, 95% confidence interval = 0.75 to 1.70)

In this issue of the Journal, Zeliadt et al. (3) examine the use of PSA testing in the Veterans Health Administration system following publication of the ERSPC and PLCO studies. They found that PSA testing declined by 5.5–9.1% (2.2–3.0 absolute percentage points) depending on the age group studied. Although the results were statistically significant, they were relatively small in comparison to changes following the release of information from other large clinical trials (4). For example, prescriptions for estrogen use during the 9 months following publication of the negative results from the Women’s Health Initiative declined by 32% (4).

It should come as no surprise that the amount of change in health-care provider and patient behavior following publication of the ERSPC (1) and PLCO (2) studies was more modest than that observed following the Women’s Health Initiative (4). Overdiagnosis and overtreatment are much more common in prostate cancer screening than in screening for breast, colorectal, or cervical cancer (5). For example, nearly one-third to one-half of PSA screened patients may be overdiagnosed [ie, cancer is found in men who would not have clinical symptoms during their lifetime (6,7)], and most of these men with low-risk prostate cancer proceed to aggressive local therapy (eg, surgery or radiation) (8).

The net effect is that many men (one-third to one-half of the 82/1000 men diagnosed by screening) are needlessly treated to realize a moderate benefit (absolute decrease of 0.71 deaths/1000 men), and some may consider this degree of overtreatment too high. Others, however, have interpreted the data as more equivocal (9) and, in the case of some guidelines (10,11), even supportive of screening. When faced with data that could be interpreted as neither strongly supportive nor decidedly unfavorable, it is natural that health-care providers and their patients might not substantially alter their practices in regard to PSA screening and, therefore, the results of Zeliadt et al. (3) should not be unexpected.

The uncertainty and limitations of PSA screening have long been recognized, and the anticipated benefits, if present, have always been thought to be moderate .These assumptions have been the basis for the requirement for the large sample sizes and extended follow-up in the design of PSA screening trials such as PLCO and ERSPC .

Many have tried to improve on the usefulness of PSA testing by adding other variables (eg, race, family history, or history of prostatic disease) or measures of PSA (eg, free PSA, PSA isoforms, or the rate of rise of PSA levels [PSA velocity]) into the decision-making process, but despite extensive research, no magic formula that incorporates such PSA values or calculations, along with the results of several other variables, has emerged to substantially improve the accuracy of screening.

As a consequence, organizations such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) have recommended that other variables and derivations of PSA testing be considered but have not provided explicit instructions on how they should actually be used .

Using the control arm of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial that randomly assigned healthy men to finasteride or placebo, Vickers et al. (14) in this issue of the Journal assessed whether information about PSA velocity (change in PSA over an 18- to 24-month period) increased the accuracy of screening when added to standard PSA values, digital rectal examination results, family history of prostate cancer, or a history of a prostate biopsy.

The authors found that triggering biopsies based on the commonly recommended PSA velocity threshold of greater than 0.35 ng mL−1 y−1 found in several guidelines would lead to a large number of additional biopsies, with close to one in seven men ultimately receiving a biopsy compared with one in 20 men when 4.0 ng/mL is used as the cutoff .Because PSA velocity did not enhance outcomes or improve the detection of more aggressive cancers ,the authors conclude that PSA velocity did not add predictive accuracy beyond PSA values alone and noted that one would be better off lowering the threshold for biopsy rather than adding PSA velocity as a criterion for biopsy

So how do these two studies influence our clinical practices? PSA testing in the Veterans Health Administration system is less frequent than in the general US population (16) and may also differ in other ways compared with the general US health-care system, so we must be careful not to overgeneralize the results of Zeliadt et al. (3). Nonetheless, the data from Zeliadt et al. (3) suggest that a possible interpretation of the results of the PLCO and ERSPC studies may be that the net results did not clearly argue for or against screening.

Under these circumstances, it would be reasonable to continue to adhere to a shared decision-making model between patient and physician, as recommended by most current guidelines ,when determining whether to proceed with PSA screening.

The results from Vickers et al. suggest that using PSA velocity may not provide more information to either physician or patient as we try to come to a decision about interpreting the results of any screening. In addition, PSA velocity measurements take time to acquire, and recognizing that such data add relatively little information may help prevent inappropriate postponement of follow-up in affected patients. Avoiding the wait to acquire subsequent PSA values may also help reduce some of the anxiety associated with testing.

The studies by Zeliadt et al. and Vickers et al. help us refine and focus our clinical approach, but they also remind us that the use of PSA as a screening tool still leaves much to be desired. Indeed, after more than 20 years of PSA screening, it has been estimated that approximately 1 million men may have been unnecessarily treated for clinically insignificant prostate cancer .

• © The Author 2011. Published by Oxford University Press.

The shortcomings of PSA testing also remind us that there is still much art to the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer and that we, like the medieval physician Maimonides, must rely not only on our scientific skills but also on a combination of clear vision, kindness, and sympathy, as we see our patients through this often challenging disease.

Treatment of Localized Prostate Cancer in the Era of PSA Screening

Watchful waiting is appropriate in older men with localized cancers.Many experts are concerned about overly aggressive treatment of clinically insignificant prostate cancer that is detected by prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening. Researchers used linked Medicare and cancer registry databases to assess mortality in 14,516 older men (age, >65; median age, 78) with diagnoses of localized (stage T1 or T2) prostate cancer during the early era of PSA testing (1992–2002) who did not die or receive prostatectomy or radiation during the first year after their diagnoses (median follow-up, about 8 years).

For patients with highly, moderately, and poorly differentiated cancers, 10-year prostate cancer–specific mortality was 8%, 9%, and 26%, respectively; mortality from all other causes was about 60% in all three groups. Most men received androgen-deprivation therapy, but only about 2% received chemotherapy, and about 1% underwent spinal surgery or radiation therapy during follow-up.

Comment: Ten-year prostate cancer–specific mortality in older men with localized disease was roughly 60% lower than that in historical controls from the 1970s and 1980s (before PSA screening was used widely). This finding could be due to several factors, including lead-time bias (apparent reduced mortality simply because cancer was diagnosed earlier but followed the same course), changes over time in how prostate cancers are graded, overdiagnosis of less-aggressive disease by PSA testing than by prostate palpation, or improved medical care. In any case, after diagnosis of highly or moderately differentiated cancer in older men, watchful waiting appears to be appropriate.

Published in Journal Watch General Medicine October 15, 2009

Early Detection of Apoptosiseasy differentiation of apoptosis and necrosis

Annexin V Kits…allow for the rapid, specific, and quantitative identification of apoptosis in individual cells. Annexin V is a calcium-dependent phospholipid binding protein. During apoptosis, an early and ubiquitous event is the exposure of phosphatidylserine at the cell surface. Trevigen's Annexin V kits have been cited in over 300 peer-reviewed research articles. Trevigen offers Annexin V conjugated to either FITC or to biotin for the detection of cell surface changes during apoptosis. The Annexin V conjugates are supplied with an optimized binding buffer and propidium iodide.Propidium iodide may be used on unfixed samples to determine the population of cells that have lost membrane integrity, an indication of late apoptosis or necrosis.

Apoptosis Trevigen's TUNEL-based assays are available in several formats with multiple options for labeling and counterstaining. The TACS•XL® kit is based on incorporation of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) at the 3’ OH ends of the DNA fragments that are formed during apoptosis. Our TACS® 2 TdT Kits utilize Trevigen’s unique cation optimization system as well as a number of proprietary reagents to enhance labeling within particulartissue types. Kits are available with several different label options, enabling you to create a system that works in your laboratory under your experimental conditions.

TACS® Annexin V Kits

• TACS® Annexin V Kits allow rapid, specific, and quantitative identification of apoptosis in individual cells. Annexin V is a calcium-dependent phospholipid binding protein. During apoptosis, an early and ubiquitous event is the exposure of phosphatidylserine at the cell surface. Trevigen offers annexin V conjugated to either FITC or to biotin for the detection of cell surface changes during apoptosis. The annexin V conjugates are supplied with an optimized Binding Buffer and propidium iodide. Propidium iodide may be used on unfixed samples to determine the population of cells that have lost membrane integrity, an indication of late apoptosis or necrosis.Diagnostic Criteria, Diagnostic Evaluation, and Staging System for Multiple Myeloma.

Diagnostic criteria• At least 10% clonal bone marrow plasma cells

• Serum or urinary monoclonal protein

• Myeloma-related organ dysfunction (CRAB criteria)

• Hypercalcemia (serum calcium >11.5 mg/dl [2.88 mmol/liter])

• Renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >2 mg/dl [177 μmol/liter])

• Anemia (hemoglobin <10 g/dl or >2 g/dl below the lower limit of the normal range)

• Bone disease (lytic lesions, severe osteopenia, or pathologic fracture)

nejm.org march 17, 2011

Diagnostic evaluation

Medical history and physical examination Routine testing: complete blood count, chemical analysis with calcium and creatinine, serum and urine protein electrophoresis with immunofixation,quantification of serum and urine monoclonal protein,measurement of free light chains Bone marrow testing: trephine biopsy and aspirate of bone-marrow cells for morphologic features; cytogenetic analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization for chromosomal abnormalities Imaging: skeletal survey, magnetic resonance imaging if skeletal survey is negative Prognosis Routine testing: serum albumin, β2-microglobulin, lactate dehydrogenase.

Staging

International Staging SystemStage I: serum β2-microglobulin <3.5 mg/liter, serum albumin ≥3.5 g/dl

Stage II: serum β2-microglobulin, <3.5mg/liter plus serum albumin <3.5 g/dl; or serum β2-microglobulin 3.5 to <5.5 mg/liter regardless of serum albumin level

Stage III: serum β2-microglobulin ≥5.5 mg/liter

Chromosomal abnormalities

High-risk: presence of t(4;14) or deletion 17p13 detected by fluorescence

in situ hybridization Standard-risk: t(11;14) detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization.

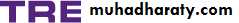

Suggested Approach to the Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma.

Several of the listed drug regimens are currently being evaluated in investigational trials. These include combination induction therapywith bortezomib and dexamethasone plus cyclophosphamide or lenalidomide, maintenance therapy with thalidomide or lenalidomide in

younger patients, and melphalan–prednisone–lenalidomide followed by maintenance therapy with lenalidomide in elderly patients.

If autologous stem-cell transplantation is delayed until the time of relapse, bortezomib-based regimens should be continued for eight cycles,

whereas lenalidomide-based regimens should be continued until disease progression or the development of intolerable side effects.

The New England Journal of Medicine.

In Western countries, the frequency of myeloma

is likely to increase in the near future as the populationages. The recent introduction of thalidomide,

lenalidomide, and bortezomib has changed

the treatment paradigm and prolonged survival

of patients with myeloma.

nejm.org march 17, 2011

At diagnosis, regimens that are based on bortezomib or lenalidomide,followed by autologous transplantation,are recommended in transplantation-eligible patients.

Combination therapy with melphalan and

prednisone plus either thalidomide or bortezomib

is suggested in patients who are not eligible

for transplantation.

Maintenance therapy with thalidomide or lenalidomide improves progression-free survival, but longer follow-up is needed to assess the effect on overall survival. At relapse, combination therapies with dexamethasone plus bortezomib, lenalidomide, or thalidomide or with

bortezomib plus liposomal doxorubicin are widely used. In the case of cost restrictions, combinations including glucocorticoids, alkylating agents,or thalidomide should be the minimal requirement for treatment.

The Tumor Lysis Syndrome

The tumor lysis syndrome is the most common disease-related emergency encountered by physicians caring for children or adults with hematologic cancers. Although it develops most often in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or acute leukemia, its frequency is increasing among

patients who have tumors that used to be only rarely associated with this complication.

The tumor lysis syndrome occurs when tumor cells release their contents into the bloodstream, either spontaneously or in response to therapy, leading to the characteristic findings of

hyperuricemia, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia,

and hypocalcemia.

These electrolyte and metabolic disturbances can progress to clinical toxic effects, including renal insufficiency, cardiac arrhythmias, seizures,and death due to multiorgan failure.

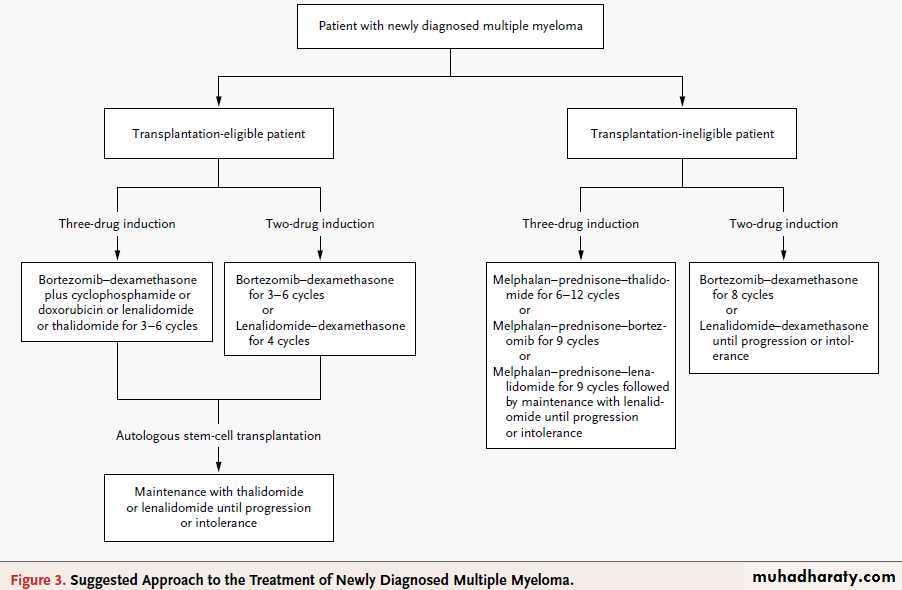

Pathophysiology

When cancer cells lyse, they release potassium,phosphorus, and nucleic acids, which are metabolized

into hypoxanthine, then xanthine, and finally

uric acid, an end product in humans (Fig. 1).12

Hyperkalemia can cause serious — and occasionally

fatal — dysrhythmias. Hyperphosphatemia can

cause secondary hypocalcemia, leading to neuromuscular. irritability (tetany), dysrhythmia, and

seizure, and can also precipitate as calcium phosphate

crystals in various organs (e.g., the kidneys,

where these crystals can cause acute kidney injury).

Uric acid can induce acute kidney injury not

only by intrarenal crystallization but also by crystal-independent mechanisms, such as renal vasoconstriction,

impaired autoregulation, decreased

renal blood flow, oxidation, and inflammation.

Tumor lysis also releases cytokines that cause a

systemic inflammatory response syndrome and

often multiorgan failure.

The tumor lysis syndrome occurs when more

potassium, phosphorus, nucleic acids, and cytokinesare released during cell lysis than the body’s

homeostatic mechanisms can deal with. Renal excretion is the primary means of clearing urate,

xanthine, and phosphate, which can precipitate

in any part of the renal collecting system. The

ability of kidneys to excrete these solutes makes

clinical tumor lysis syndrome unlikely without the

previous development of nephropathy and a consequent inability to excrete solutes quickly enough to cope with the metabolic load.

Crystal-induced tissue injury occurs in the tumor

lysis syndrome when calcium phosphate, uricacid, and xanthine precipitate in renal tubules and

cause inflammation and obstruction .

A high level of solutes, low solubility, slow urine

flow, and high levels of cocrystallizing substances

favor crystal formation and increase the severity

of the tumor lysis syndrome.

High levels of both uric acid and phosphate render patients with the tumor lysis syndrome at particularly high risk for crystal-associated acute kidney injury,

because uric acid precipitates readily in the presence

of calcium phosphate, and calcium phosphate

precipitates readily in the presence of uric acid.

Also, higher urine pH increases the solubility of

uric acid but decreases that of calcium phosphate.

In patients treated with allopurinol, the accumulation

of xanthine, which is a precursor of uric acid and has low solubility regardless of urine pH, can lead to xanthine nephropathy or urolithiasis.

Calcium phosphate can precipitate throughout

the body .The risk of ectopic calcificationis particularly high among patients who receive

intravenous calcium. When calcium phosphate

precipitates in the cardiac conducting system,

serious, possibly fatal, dysrhythmias can occur.

Acute kidney injury developed in our patient as

a result of the precipitation of uric acid crystalsand calcium phosphate crystals and was exacerbated

by dehydration and acidosis that developed

because the tumor lysis syndrome had not been

suspected and no supportive care was provided.

Figure 1. Lysis of Tumor Cells and the Release of DNA, Phosphate, Potassium, and Cytokines.

The graduated cylinders shown in Panel A contain leukemic cells removed by leukapheresis from a patient with T-cell

acute lymphoblastic leukemia and hyperleukocytosis (white-cell count, 365,000 per cubic millimeter). Each cylinder contains

straw-colored clear plasma at the top, a thick layer of white leukemic cells in the middle, and a thin layer of red

cells at the bottom. The highly cellular nature of Burkitt’s lymphoma is evident in Panel B (Burkitt’s lymphoma of the

appendix, hematoxylin and eosin). Lysis of cancer cells (Panel C) releases DNA, phosphate, potassium, and cytokines.

DNA released from the lysed cells is metabolized into adenosine and guanosine, both of which are converted into xanthine.

nejm.1854 org may 12, 2011

Xanthine is then oxidized by xanthine oxidase, leading to the production of uric acid, which is excreted by the kidneys.When the accumulation of phosphate, potassium, xanthine, or uric acid is more rapid than excretion, the tumor lysis syndrome develops. Cytokines cause hypotension, inflammation, and acute kidney injury, which increase the risk for the tumor lysis syndrome. The bidirectional dashed line between acute kidney injury and tumor lysis syndrome indicates that acute kidney injury increases the risk of the tumor lysis syndrome by reducing the ability of the kidneys to excrete uric acid, xanthine, phosphate, and potassium.

By the same token, development of the tumor lysis syndrome can cause acute kidney injury by renal precipitation of uric acid, xanthine, and calcium phosphate crystals and by crystalindependent

mechanisms. Allopurinol inhibits xanthine oxidase (Panel D) and prevents the conversion of hypoxanthine and xanthine into uric acid but does not remove existing uric acid.

In contrast, rasburicase removes uric acid by enzymatically degrading it into allantoin, a highly soluble product that has no known adverse effects on health.

Management

Optimal management of the tumor lysis syndromeshould involve preservation of renal function. Management

should also include prevention of dysrhythmias

and neuromuscular irritability .

Prevention of acute kidney injury

All patients who are at risk for the tumor lysis

syndrome should receive intravenous hydration

to rapidly improve renal perfusion and glomerular

filtration and to minimize acidosis (which lowers urine pH and promotes the precipitation of uric acid crystals) and oliguria (an ominous sign). This is usually accomplished with hyperhydration by means of intravenous fluids (2500 to 3000 ml per square meter per day in the patients at highest risk). Hydration is the preferred method of increasing urine output, but diuretics may also be necessary.

In a study involving a rat model of urate nephropathy with elevated serum uric acid levels induced by continuous intravenous infusion of high doses of uric acid, high rine output due to treatment with high-dose furosemide or congenital diabetes insipidus (in the group of mice with this genetic modification)

protected the kidneys equally well, whereas acetazolamide (mild diuresis) and bicarbonate provided only moderate renal protection (no more

than a low dose of furosemide without bicarbonate).

Hence, in patients whose urine output remains

low after achieving an optimal state of hydration, we recommend the use of a loop diuretic agent (e.g., furosemide) to promote diuresis, with a target urine output of at least 2 ml per kilogram per hour.Reducing the level of uric acid, with the use of allopurinol and particularly with the use of rasburicase, can preserve or improve renal function and reduce serum phosphorus levels as asecondary beneficial effect. Although allopurinol prevents the formation of uric acid, existing uric acid must still be excreted.

The level of uric acid may take 2 days or more to decrease, a delay that allows urate nephropathy to develop .Moreover, despite treatment with allopurinol, xanthine may accumulate,resulting in xanthine nephropathy.

Since the serum xanthine level is not routinely

measured, its effect on the development of acute

kidney injury is uncertain. By preventing xanthine

accumulation and by directly breaking down uric

acid, rasburicase is more effective than allopurinol

for the prevention and treatment of the tumor

lysis syndrome.

In a randomized study of the use of allopurinol versus rasburicase for patients at risk for the tumor lysis syndrome, the mean serum phosphorus level peaked at 7.1 mg per deciliter (2.3 mmol per liter) in the rasburicase group (and mean uric acid levels decreased by 86%, to 1 mg per deciliter [59.5 μmol per liter] at 4 hours) as compared with 10.3 mg per decili ter (3.3 mmol per liter) in the allopurinol group (and mean uric acid levels decreased by 12%, to 5.7 mg per deciliter [339.0 μmol per liter] at 48

hours).

The serum creatinine level improved (decreased) by 31% in the rasburicase group but worsened (increased) by 12% in the allopurinol

group. Pui and colleagues40 documented no increases in phosphorus levels and decreases in

creatinine levels among 131 patients who were at

high risk for the tumor lysis syndrome and were

treated with rasburicase.

Finally, in a multicenter study involving pediatric patients with advancedstage Burkitt’s lymphoma, in which all patients received identical treatment with chemotherapy and aggressive hydration, the tumor lysis syndrome occurred in 9% of 98 patients in France (who received rasburicase) as compared with 26% of 101 patients in the United States (who received allopurinol) (P = 0.002).33 Dialysis was required in only 3% of the French patients but 15% of the patients in the United States (P = 0.004). At the

time of the study, rasburicase was not available in

the United States.

Urinary alkalinization increases uric acid solubility

but decreases calcium phosphate solubility(Fig. 1a in the Supplementary Appendix).

Because it is more difficult to correct hyperphosphatemia than hyperuricemia, urinary alkalinization should be avoided in patients with

the tumor lysis syndrome, especially when rasburicase is available.

Whether urine alkalinization prevents or reduces the risk of acute kidney injury in patients without access to rasburicase is unknown, but the animal model of urate nephropathy suggested no benefit. If alkalinization is used, it should be discontinued when hyperphosphatemia develops.

In patients treated with rasburicase, blood samples for the measurement of the uric acid level must be placed on ice to prevent ex vivo breakdown of uric acid by rasburicase and thus a spuriously low level. Patients

with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

should avoid rasburicase because hydrogen peroxide,

a breakdown product of uric acid, can cause

methemoglobinemia and, in severe cases, hemolytic

anemia. Rasburicase is recommended as

first-line treatment for patients who are at high

risk for clinical tumor lysis syndrome.

Because of cost considerations and pending pharmacoeconomic studies, no consensus has been reached on rasburicase use in patients who are at intermediate risk for the tumor lysis syndrome; some have advocated use of a small dose of rasburicase in such patients. Patients who are at low risk can usually

be treated with intravenous fluids with or

without allopurinol, but they should be monitored

daily for signs of the tumor lysis syndrome.

Prevention of cardiac dysrhythmias

and neuromuscular irritabilityHyperkalemia remains the most dangerous component

of the tumor lysis syndrome because it can cause sudden death due to cardiac dysrhythmia.

Patients should limit potassium and phosphorus

intake during the risk period for the tumor lysis syndrome. Frequent measurement of potassium

levels (every 4 to 6 hours), continuous cardiac

monitoring, and the administration of oral sodium

polystyrene sulfonate are recommended in

patients with the tumor lysis syndrome and acute

kidney injury.

Hemodialysis and hemofiltration effectively remove potassium. Glucose plus insulin or beta-agonists can be used as temporizing measures, and calcium gluconate may be used to reduce the risk of dysrhythmia while awaiting hemodialysis.

Hypocalcemia can also lead to life-threatening

dysrhythmias and neuromuscular irritability; controlling the serum phosphorus level may prevent hypocalcemia.

Symptomatic hypocalcemia should be treated with calcium at the lowest dose required to relieve symptoms, since the administration

of excessive calcium increases the calcium–

phosphate product and the rate of calcium

phosphate crystallization, particularly if the product is greater than 60 mg2 per square deciliter.

Hypocalcemia not accompanied by signs or symptoms does not require treatment.

Despite the lack of studies that show the efficacyof phosphate binders in patients with the tumor

lysis syndrome, this treatment is typically given.

Management of severe acute kidney injury

Despite optimal care, severe acute kidney injurydevelops in some patients and requires renal replacement therapy .Although the indications for renalreplacement therapy in patients with the tumor

lysis syndrome are similar to those in patients with

other causes of acute kidney injury, somewhat

lower thresholds are used for patients with the

tumor lysis syndrome because of potentially rapid

potassium release and accumulation, particularly

in patients with oliguria.

In patients with the tumor lysis syndrome, hyperphosphatemia-induced symptomatic hypocalcemia may also warrant dialysis.

Phosphate removal increases as treatment

time increases, which has led some to advocate

the use of continuous renal-replacement therapies in patients with the tumor lysis syndrome, including continuous venovenous hemofiltration, continuous venovenous hemodialysis, or continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration.

These methods of dialysis use filters with a larger pore size, which allows more rapid clearance of molecules that are not efficiently removed by conventional hemodialysis.

One study that compared phosphate levels among

adults who had acute kidney injury that was treated

with either conventional hemodialysis or continuous

venovenous hemodiafiltration showed that

continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration more effectively reduced phosphate.

Much less is known about the dialytic clearance of uric acid, but in countries where rasburicase is available, hyperuricemia is seldom an indication for dialysis.

In our patient, once the tumor lysis syndrome was identified, treatment with intravenous fluids,

phosphate binders, and rasburicase prevented

the need for dialysis. Despite a potassium level

of 5.9 mmol per liter, he had no dysrhythmia or

changes on electrocardiography, but had he presented 1 day later, the tumor lysis syndrome may have proved fatal.

Monitoring

Urine output is the key factor to monitor in patientswho are at risk for the tumor lysis syndrome

and in those in whom the syndrome has developed.

In patients whose risk of clinical tumor lysis

syndrome is non-negligible, urine output and fluid

balance should be recorded and assessed frequently.

Patients at high risk should also receive intensive

nursing care with continuous cardiac monitoring

and the measurement of electrolytes, creatinine,

and uric acid every 4 to 6 hours after the start of

therapy.

Those at intermediate risk should undergo

laboratory monitoring every 8 to 12 hours,

and those at low risk should undergo such monitoring

daily. Monitoring should continue over the

entire period during which the patient is at risk

for the tumor lysis syndrome, which depends on

the therapeutic regimen.

In a protocol for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, which featured up-front,single-agent methotrexate treatment, new-onset

tumor lysis syndrome developed in some patients

at day 6 or day 7 of remission-induction therapy

(after the initiation of combination chemotherapy

with prednisone, vincristine, and daunorubicin

on day 5 and asparaginase on day 6).

Decreasing the rate of tumor lysis

with a treatment prephasePatients at high risk for the tumor lysis syndrome

may also receive low-intensity initial therapy. Slower

lysis of the cancer cells allows renal homeostatic

mechanisms to clear metabolites before they

accumulate and cause organ damage. This strategy,

in cases of advanced B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

or Burkitt’s leukemia, has involved treatment

with low-dose cyclophosphamide, vincristine,

and prednisone for a week before the start of intensive

chemotherapy.

nejm.1854 org may 12, 2011

Better Evidence about Screening for Lung Cancer

nejm.org august 4, 2011

In October 2010, the National Cancer Institute

(NCI) announced that patients who were randomlyassigned to screening with low-dose computed

tomography (CT) had fewer deaths from lung cancer than did patients randomly assigned to screening with chest radiography.

The first report of

the NCI-sponsored National Lung Screening Trial

(NLST) in a peer-reviewed medical journal appears

in this issue of the Journal.

Eligible participants were between 55 and 74

years of age and had a history of heavy smoking.They were screened once a year for 3 years and

were then followed for 3.5 additional years with

no screening. At each round of screening, results

suggestive of lung cancer were nearly three times

as common in participants assigned to low-dose

CT as in those assigned to radiography, but only

2 to 7% of these suspicious results proved to be

lung cancer.

Invasive diagnostic procedures were few, suggesting that diagnostic CT and comparison with prior images usually sufficed to rule out lung cancer in participants with suspicious screening findings.

Diagnoses of lung cancer after the screening period had ended were more common among participants who had been assigned to screening with chest radiography than among those who had been assigned to screening with low-dose CT, suggesting that radiography missed cancers during the screening period.

Cancers discovered after a positive low-dose CT screening test were more likely to be early stage and less likely to be late stage than were those discovered after chest radiography. There were 247 deaths from lung cancer per 100,000 person-years of follow-up after screening with low-dose CT and 309 per 100,000 person-years after screening with chest radiography.

The conduct of the study left a little room for

concern that systematic differences between thetwo study groups could have affected the results

(internal validity). The groups had similar characteristics at baseline, and only 3% of the participants in the low-dose CT group and 4% in the radiography group were lost to follow-up. However,there were two systematic differences in adherence to the study protocol.

First, as shown in Figure 1 of the article, although adherence to each screening was 90% or greater in each group, it was 3 percentage points lower for the second and third radiography screenings than for the corresponding low-dose CT screenings. Because more participants in the radiography group missed one or two screenings, the radiography group had more time in which a lung cancer could metastasize before it was detected.

Second, participants in the low-dose CT group were much less likely than those in the radiography group to have adiagnostic workup after a positive result in the second and third round of screening (Table 3 of the article), which might have led to fewer screening-related diagnoses of early-stage lung cancer after low-dose CT. The potential effect of these two differences in study conduct seems to be too small to nullify the large effect of low-dose CT screening on lung-cancer mortality.

The applicability of the results to typical practice

(external validity) is mixed. Diagnostic workupand treatment did take place in the community.

However, the images were interpreted by

radiologists at the screening center, who had extra

training in the interpretation of low-dose CT

scans and presumably a heavy low-dose CT workload.

Moreover, trial participants were younger

and had a higher level of education than a ran-

dom sample of smokers 55 to 74 years of age,

which might have increased adherence to the

study protocol.

Overdiagnosis is a concern in screening for

cancer. Overdiagnosis occurs when a test detects

a cancer that would otherwise have remained occult,either because it regressed or did not grow

or because the patient died before it was diagnosed.

In a large, randomized trial comparing two screening tests, the proportion of patients in whom cancer ultimately develops should be the same in the two study groups.

A difference that persists suggests that one test is detecting cancers that would never grow large enough to be detected by the other test.

Overdiagnosis is a problem because predicting which early-stage cancers will not progress is in an early stage of development,

so that everyone with screen-detected cancer

receives treatment that some do not need.

Overdiagnosis biases case-based measures (e.g.,case fatality rate) but not the population-based measures used in the NLST.

Overdiagnosis probably occurred in the NLST.

After 6 years of observation, there were 1060 lungcancers in the low-dose CT group and 941 in the

radiography group. Presumably, some cancers in

the radiography group would have been detectable

by low-dose CT but grew too slowly to be

detected by radiography during the 6.5 years of

observation. The report of the Mayo Lung Project

provides strong evidence that radiographic screening

causes overdiagnosis of lung cancer.

At the end of the follow-up phase in the Mayo study,

more lung cancers were diagnosed in the group

screened with radiography and sputum cytologic

analysis than in the unscreened group. This gap

did not close, as would be expected if undetected

cancers in the unscreened group continued to

grow; the gap grew and then leveled off at 69

additional lung cancers in the screened group at

12 and 16 years.

The Mayo study shows that 10 to 15 additional years of follow-up will be necessary

to test the hypothesis that low-dose CT in theNLST led to overdiagnosis. If the difference in

the number of cancers in the two groups of the

NLST persists, overdiagnosis in the low-dose CT

group is the likely explanation.

The incidence of lung cancer was similar at

the three low-dose CT screenings (Table 3 of the

article), which implies that a negative result of

low-dose CT screening did not substantially reduce

the probability that the next round would detect cancer. Lung cancer was also diagnosed frequently during the 3 years of follow-up after the third low-dose CT screening. Apparently,every year, there are many lung cancers that first become detectable that year. This observation, together with the overall NLST results, suggests that

continuing to screen high-risk individuals annually

will provide a net benefit, at least until deaths

from coexisting chronic diseases limit the gains

in life expectancy from screening.

The NLST results show that three annual rounds of low-dose CT screening reduce mortality from lung cancer, and that the rate of death associated with diagnostic procedures is low.

How should policy makers (those responsible

for screening guidelines, practice measures, and

insurance coverage) respond to this important

result? According to the authors, 7 million U.S.

adults meet the entry criteria for the NLST,1 and

an estimated 94 million U.S. adults are current

or former smokers.

With either target population,a national screening program of annual low-dose CT would be very expensive, which is why I agree with the authors that policy makers should wait for more information before endorsing lung-cancer screening programs.

Policymakers should wait for cost-effectiveness

analyses of the NLST data, further follow-up data

to determine the amount of overdiagnosis in the

NLST, and, perhaps, identification of biologic

markers of cancers that do not progress.

Modeling should provide estimates of the effect of

longer periods of annual screening and the effect

of better adherence to screening and diagnostic

evaluation. Systematic reviews that include

other, smaller lung-cancer screening trials will

provide an overview of the entire body of evidence.

Finally, it may be possible to define subgroups

of smokers who are at higher or lower risk

for lung cancer and tailor the screening strategy

accordingly.

Individual patients at high risk for lung cancer

who seek low-dose CT screening and their primarycare physicians should inform themselves

fully, and current smokers should also receive redoubled assistance in their attempts to quit smoking.

They should know the number of patients

needed to screen to avoid one lung-cancer death,

the limited amount of information that can be

gained from one screening test, the potential for overdiagnosis and other harms, and the reduction

in the risk of lung cancer after smoking cessation.

The NLST investigators report newly proven

benefits to balance against harms and costs,

so that physicians and patients can now have

much better information than before on which

to base their discussions about lung-cancer

screening.

The findings of the NLST regarding lung-cancer

mortality signal the beginning of the end of

one era of research on lung-cancer screening and

the start of another. The focus will shift to informing

the difficult patient-centered and policy

decisions that are yet to come.

nejm.org august 4, 2011

Cancer Cachexia and Fat–Muscle Physiology

nejm.org august 11, 2011Cachexia affects the majority of patients with advanced cancer and is associated with a reduction

in treatment tolerance, response to therapy, quality

of life, and duration of survival.

It is a multifactorial

syndrome caused by a variable combination

of reduced food intake and abnormal

metabolism that results in negative balances of

energy and protein.

Cachexia is defined by an ongoing loss of skeletal-muscle mass and leads to progressive functional impairment.

Although appetite stimulants or nutritional support can help reverse the loss of fat, the reversal of muscle wasting is much more difficult and remains a challenge in patient care.

The loss of skeletal muscle in cachexia is the

result of an imbalance between protein synthesisand degradation. Much recent work has focused

on the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, the regulation

of satellite cells in skeletal muscle, and the

importance of related receptors and signaling

pathways that are probably influenced by tumorinduced systemic inflammation.

Similarly, the loss of adipose tissue results from an imbalance in lipogenesis and lipolysis, with enhanced lipolysis driven by neuroendocrine activation and tumor-related lipolytic factors, including proinflammatory cytokines and zinc-α2-glycoprotein.

The study of integrative physiology in obesity

and diabetes has long emphasized the importanceof chronic inflammation, increased adipocyte

lipolysis, and increased levels of circulating

free fatty acids in the adipose–muscle cross-talk

that contributes to lipotoxicity and insulin resistance

in muscle. Similarly, studies in exercise

physiology have focused on the molecular crosstalk

between adipose tissue and muscle that occurs

through adipokines and myokines and on

the role these molecules may play in chronic diseases.

Although cachexia in patients with cancer

is characterized by systemic inflammation, increased

lipolysis, insulin resistance, and reduced

physical activity, there has been little effort to

manipulate the integrative physiology of adipose

tissue and muscle tissue for therapeutic gain.

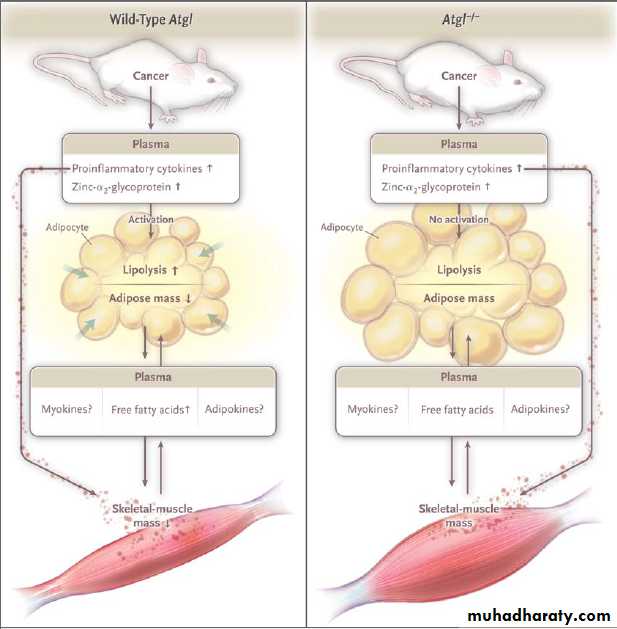

To this end, Das and colleagues recently reported

the results of experiments involving two

mouse models in which the metabolic end of the

cachexia–anorexia spectrum was investigated.

In these mice, during the early and intermediate

phases of tumor growth and cachexia, food intakeremained normal while plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines and zinc-α2-glycoprotein

rose. The investigators found that genetic ablation

of adipose triglyceride lipase prevented the

increase in lipolysis and the net mobilization of

adipose tissue associated with tumor growth

Unexpectedly, they also observed that skeletal-muscle mass was preserved and that activation of proteasomal-degradation and apoptotic

pathways in muscle was averted. Ablation of

hormone-sensitive lipase had similar but weaker

effects. This study opens up the possibility that

hitherto unrecognized, physiologically important

cross-talk between adipose tissue and skeletal

muscle exists in the context of cancer cachexia.

What is the translational relevance of these

findings? Given the current epidemic of obesity

in Western society in general and in patients

with cancer in particular, the inhibition of fat

loss is probably not a priority in itself. The key

problem remains low muscle mass, with up to

50% of persons with advanced cancer having

frank sarcopenia. Moreover, the shortest survival

times among patients with advanced cancer may

be among obese patients with sarcopenia.

In such patients, any muscle-preserving therapy

that also increases fat mass might not be advantageous.It should also be considered that the

metabolic response to cancer is heterogeneous,

and a therapy that is tailored to a specific metabolic

abnormality may require specific, individualized

characterization of patients. Moreover,

cachexia has a spectrum of phases (precachexia,

cachexia, and refractory cachexia) and degrees of severity.

Das and colleagues tested the effect of ablation of lipolysis at the onset of tumor growth. Thus, their model does not address the scenario that frequently occurs in clinical practice, in which both cancer and cachexia are well established.

Finally, patients generally receive systemic antineoplastic therapy until a late stage

in their disease trajectory, and the interaction of

this treatment with the development of cachexia

(some treatments may induce muscle wasting) is unknown.

Model of Cachexia and Lipolysis in Tumor-Bearing Mice with Wild-Type Atgl or Atgl−/−.

In tumor-bearing mice with the wild-type gene for adipose triglyceride lipase (Atgl, also known as Pnpla2), a variety of circulating mediators, including cytokines (tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin-6) and zinc-α2-glycoprotein,activate Atgl, which triggers lipolysis, resulting in net mobilization of white adipose tissue and an increase in plasma levels of free fatty acids. Concomitantly, cachexia — the process of protein catabolism, apoptosis, and muscle atrophy — begins and may be modulated by cross-talk between muscle and adipose tissue mediated by free fatty acids or by various adipokines or myokines. In tumor-bearing mice in which the Atgl −/− gene has been ablated, the same pattern of mediator release fails to activate lipolysis, plasma levels of free fatty acids remain normal, and both white adipose tissue mass and skeletal-muscle mass are maintained. The mechanism through which skeletal-muscle mass is maintained in the presence of the systemic mediators is unknown but may involve muscle-adipose cross-talk

through free fatty acids, myokines, or adipokines. Alternatively, the maintenance of skeletal-muscle mass may be adirect consequence of autonomous lipolysis in defective tissue.

Taken together, these issues point to the importance of understanding the precise mechanism underlying the findings of Das and colleagues.

Traditionally, controlling the advance of cancer

has been viewed as the best way to contain

cachexia. However, symptom management alone

can improve survival in patients with advanced

cancer, and a multifaceted approach to the management of cachexia has already proved to be

partially effective.

The growing understanding of the mechanisms underpinning cachexia has prompted an increasing number of studies, now in phase 1 or phase 2, that use highly specific, potent therapies targeted at either upstream mediators or downstream end-organ hypoanabolism and hypercatabolism. The study by Das and colleagues suggests that achieving a better understanding of the integrative physiology of this

complex syndrome may yield yet further novel

therapeutic approaches.

Nejm.org august 11, 2011

Management of BPH and Prostate Cancer Reviewed

MedscapeCME Clinical Briefs © 2010November 23, 2010 — Watchful waiting or active surveillance are options in selected patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostate cancer, according to a review reported in the December issue of the International Journal of Clinical Practice.

"...BPH and prostate cancer (CaP) are major sources of morbidity in older men," write J. Sausville and M. Naslund, from the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore. "Management of these disorders has evolved considerably in recent years. This article provides a focused overview of BPH and CaP management aimed at primary care physicians."

BPH may give rise to troublesome lower urinary tract symptoms and/ or acute urinary retention. Acute urinary retention may be associated with an increased risk for recurrent urinary tract infections; bladder calculi; and, occasionally, renal insufficiency.

BPH may be managed with medications, minimally invasive therapies, and prostate surgery.

First-line treatment in men presenting with lower urinary tract symptoms from BPH is typically pharmacotherapy with

alpha-blockers or 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors. Alpha-blockers generally work within a few days by relaxing smooth muscle, whereas 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors may take 6 to 12 months to relieve urinary symptoms. The latter drug class blocks the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, thereby shrinking hyperplastic prostate tissue.

Malignant disease in men older than 50 years with lower urinary tract symptoms can largely be excluded by normal results on digital rectal examination, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood testing, and urinalysis.

However, elevated PSA levels and/or a nodular prostate may be red flags for prostate cancer, and microscopic hematuria with urinary symptoms may suggest bladder cancer or prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer is a highly prevalent condition, and outcomes may be better with early detection. Although 2 large clinical trials have recently been published supporting screening for prostate cancer,

mass screening is still considered controversial.

"The ageing of the population of the developed world means that primary care physicians will see an increasing number of men with BPH and CaP," the review authors write. "Close collaboration between primary care physicians and urologists offers the key to successful management of these disorders."

On the basis of a review of current literature regarding BPH and prostate cancer, the study authors note that despite increasing use of effective medical treatments, surgical intervention is still a valid option for many men. New technologies have emerged for surgical management.

Open radical retropubic prostatectomy is still the oncologic reference standard, but other well-established surgical procedures include transurethral resection of the prostate as well as use of minimally invasive techniques. A new surgical technique for prostate cancer management, now under more widespread use, is robot-assisted prostatectomy.

Other options for treatment of prostate cancer include radiation therapy, brachytherapy, high-intensity focused ultrasound, and cryotherapy. The review authors also note that not all men with prostate cancer necessarily need to be treated and that watchful waiting or active surveillance may be appropriate in some patients.

Various protocols exist for identifying low-risk CaP and some such patients may be offered active surveillance," the review authors write. "To mitigate the danger of under-grading, these patients typically undergo repeated prostate biopsies at predetermined intervals, and PSA levels and DRE [digital rectal examination] findings are monitored. If progression of disease (increased PSA, PSAV [PSA velocity], or discovery of higher grade or bulkier cancer on biopsy) occurs, definitive therapy is offered."

Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:1740-1745.

Clinical Context

BPH and prostate cancer are common conditions among older men. More than half of men older than 50 years have BPH, which usually presents clinically with symptoms of lower urinary tract obstruction. Prostate cancer can have a similar presentation, and it is the most common nonskin cancer diagnosed among men in the United States.The current review highlights the diagnosis and management of BPH and prostate cancer, with a focus on emerging therapeutic options.

Study Highlights

Malignant disease of the prostate can usually be differentiated from BPH with a digital rectal examination, PSA level testing, and a urinalysis. A PSA value of 1.5 ng/mL correlates with a prostate volume of 30 g, which is regarded as enlarged.Examination of a postvoid residual volume is not necessary among men with suspected BPH, but an elevated postvoid residual volume suggests a worse prognosis of BPH.

The primary management of most cases of BPH is medical therapy. Alpha-blockers can reduce symptoms within days, whereas 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors can take 6 to 12 months to relieve urinary symptoms.

Of these 2 classes of medications, only 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors reduce the risk for urinary retention and the need for prostate surgery.

A recent trial suggested a synergistic effect when alpha-blockers were used with 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors in the treatment of BPH.

Laser technology is being used in the surgical treatment of BPH, particularly among patients at risk for hemorrhage. However, the long-term effectiveness of laser treatment modalities has yet to be established.

All prostate ablative techniques carry the risks for retrograde ejaculation in 50% to 90% of patients and urinary incontinence in 1% of patients.

However, erectile function appears to be less significantly affected by current surgeries.

PSA is commonly used to diagnose prostate cancer, but assigning cutoff values for abnormal PSA is difficult. In 1 large study, 15% of men with a PSA level of less than 4.0 ng/mL had prostate cancer.

PSA levels vary by age and race, and the clinician should be aware of these variations.

A reduction in levels of unbound, or free, PSA is associated with a higher risk for prostate cancer.

5-alpha-reductase inhibitors can reduce PSA levels by approximately 50% after 12 months of treatment.

Recent large trials of screening men for prostate cancer have yielded mixed results regarding the efficacy of this intervention in reducing the risk for prostate cancer-specific mortality. The US Preventive Service Task Force finds insufficient evidence to recommend for or against screening for prostate cancer among men younger than 75 years, but it recommends against screening among men 75 years or older.

Active surveillance, which includes close follow-up of PSA values with subsequent biopsies, is considered a first-line option in the management of prostate cancer in the United Kingdom.

Localized prostate cancer can be treated with surgery or radiation therapy. Radical retropubic prostatectomy has excellent oncologic outcomes and results in urinary incontinence in less than 10% of patients. Approximately half of men have preserved erectile function after this procedure.

Radiation therapy is more widely used now in the treatment of prostate cancer, but it can promote adverse events such as hematochezia, hematuria, and irritative lower urinary tract symptoms.

High-intensity focused ultrasound has received attention as a less invasive treatment of prostate cancer, although 1 series demonstrated a biochemical complete response rate of 92% for this procedure. Cryotherapy is another emerging treatment, although it may promote higher rates of erectile dysfunction vs surgery or brachytherapy.

Luteinizing hormone release hormone analogues are the principal treatment of metastatic cancer.

Clinical Implications

Evaluation of older men with lower urinary tract symptoms should include a digital rectal examination, urinalysis, and PSA level testing. A postvoid residual volume is not usually necessary before the initiation of treatment of BPH.

Localized prostate cancer can be treated with surgery or radiation therapy, both of which are associated with particular adverse events. High-intensity focused ultrasound may not yield adequate rates of biochemical complete response, and cryotherapy may promote higher rates of erectile dysfunction vs surgery or brachytherapy.

MedscapeCME Clinical Briefs © 2010

Early PSA Predicts Prostate Cancer Risk -- But Then What?

Hello, I'm Dr. Gerald Chodak for Medscape. In October 2010, an article was published in Cancer Online [1] that looked at more than 20,000 men from Sweden who had their blood drawn and stored when they were between the ages of 33 and 50. Over time, through 2006, more than 1400 of the men were diagnosed with prostate cancer. The investigators went back and tested the blood samples of these men to see what their PSA [prostate-specific antigen] levels were up to 30 years before the diagnosis of prostate cancer was made.Medscape Urology © 2010

They found that if the PSA was > 0.63 ng/mL, they had a significant chance of developing cancer or advanced cancer many years in the future. This raises a question: What would you do with this information? The investigators suggest that it could help stratify men according to their risk.

If they have a PSA level less than that cutoff, then they could be followed less often. However, if their PSA was above that value, then more careful follow-up would be needed.

Of course, the problem with the article is that it doesn't address the implications of testing in terms of the long-term outcomes. Although these men were diagnosed with cancer, it's unclear whether this testing process would reduce their chances of dying from the disease. The study does not address the implications for predicting which men will die of prostate cancer.

So, it is another piece of information that might be used to help separate men into low- and high-risk groups, but it doesn't address the issues about screening and about changing the natural history of the disease.

It simply says that if your PSA is higher than 0.63 ng/mL, then you have a greater chance of being diagnosed with prostate cancer some time in the future.

Does that mean everyone should get a baseline test, and use that to make further decisions? I'm not sure that we can answer that at the present time.

That would need a different type of study. However, we come back to the latest meta-analysis that has raised questions about the overall impact of testing and treating men with this disease. The bottom line is that this is interesting information and warrants further evaluation to see what would be the best approach, but it doesn't find all men who have aggressive cancer, and it could turn out that men who have life-threatening disease might not have been detected 30 years earlier by using this PSA cutoff. So, I'm not sure that it should be adopted at this time, but clearly it warrants further evaluation.

December 11, 2010 (San Antonio, Texas) — A cohort of women who underwent either mastectomy or breast conservation therapy (BCT) an average of 25 years ago now have "equivalent" overall survival, according to the authors of new study from a long-term National Cancer Institute trial.

25-Year Results in Early Breast Cancer Surgery

The study of 237 women with stage 1 or 2 breast cancer was presented as a poster here at the 33rd Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

There was no statistically significant difference in overall survival in either group of the study, with 45.7% of patients alive in the mastectomy group and 38.0% alive in the BCT group (P = .43), according to the authors, led by N.L. Simonen, MD, from the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda Maryland.

However, a breast cancer surgeon from the Mayo Clinic said that the difference in survival — despite its lack of statistical importance — was concerning.

"You have to wonder whether this difference would become significant with a larger patient group," said Judy Boughey, MD, who is an associate professor of surgery at the Mayo Clinic's Rochester, Minnesota, campus.

Dr. Boughey found some comfort in other findings that compare the 2 surgical approaches. "The lack of a statistically significant difference in overall survival is in keeping with multiple previous studies," Dr. Boughey toldMedscape Medical News. She attended the meeting and was asked to comment on the poster.

The findings on local recurrence did indicate an important difference between mastectomy and BCT.

Disease-free survival was significantly worse in patients randomly assigned to receive BCT compared with mastectomy (57% vs 82%; P < .001).

The additional treatment failures in the BCT group were primarily isolated ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences, the authors point out. They also note that these recurrences were salvaged by mastectomy. In all, 22.3% of BCT patients experienced such a recurrence. However, "those patients had no significant decrease in overall survival," say the authors.

Talk About Local Recurrence Rate, Especially With Young Women

What is missing from this study is the rate of local recurrence for the mastectomy patients. "We know that it is not zero," said Dr. Boughey, "because some breast tissue remains after mastectomy."The new study is a reminder of the importance and challenges of counseling women with early breast cancer.

"A lot of women struggle with the choice of surgery," said Dr. Boughey. She reminds women that the overall survival is roughly the same, but the local recurrence rate is significantly higher if they keep the breast. "The risk of local failure exists and needs to be discussed."

For most women, Dr. Boughey recites a set of figures in her local recurrence talk. "I say to patients, if you get a lumpectomy, the risk for local recurrence at 10 years is 8% to 10%, and if you get a mastectomy, the risk is 2% to 4%."

However, when counseling young woman — that is, women younger than 40 years — the discussion about local recurrence is a bit different, and is especially important, Dr. Boughey said.

Dr. Boughey presented a poster at the symposium that indicated the risks for recurrence by decade of life. In the new retrospective study, 6.9% of 3075 patients who underwent breast-conserving surgery at the Mayo Clinic had a local recurrence at a median of 3.4 years.

The frequency of local recurrence by age group was:

Younger than 40 years: 11.9%Aged 40 to 49 years: 5.9%

Aged 50 to 59 years: 5.9%

Aged 60 to 69 years: 7.6%

Aged 70 years or older: 6.4%

The fact that the youngest women had the highest rate of recurrence is important in part, said Dr. Boughey, because they have more aggressive tumors.

Young women need to know that their risk for local recurrence is higher than other age groups, she said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

33rd Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium: Abstracts P4-10-01 and P4-10-02. Presented December 11, 2010.

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib, which targets the enzyme that results from the BCR-ABL mutation and is associated with an overall survival rate of about 89% at 5 years, revolutionized the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) during the past decade.[1,2] Since then, newer-generation TKIs, including nilotinib and dasatinib, have been developed for the treatment of CML.[3,4

Community and Expert Perspectives: 2010 Update on Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

MedscapeCME Oncology © 2010 MedscapeCME

Major studies were recently presented at the 2010 meetings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and European Hematology Association regarding the emergence of these agents, which are both approved for imatinib-intolerant or -resistant disease, as first-line therapy.

Indeed, the results of the 2 phase 3 studies of nilotinib and dasatinib were published in June 2010,[8,9] and nilotinib subsequently received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for use in the first-line treatment of adult patients with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase. At the same time, other agents are in early- and late-stage clinical development, including some that may be effective against the acquired T315I mutation in the ABL kinase domain.

In the wake of these exciting findings, Emma Hitt, PhD, spoke on behalf of MedscapeCME with Richard A. Larson, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, to discuss the evolving landscape of CML treatment. In addition, Dr. Leon Dragon, Medical Director of the Kellogg Cancer Center, NorthShore University HealthSystem, Highland Park, Chicago, weighed in (available in the accompanying downloadable PDF) on the impact of these findings for the practicing community oncologist.

Medscape: What are some of the issues involved in diagnosing CML?

Dr. Larson: Confirming the diagnosis is the critical first step in managing patients with CML. If the BCR-ABL fusion gene is present, then the behavior of the disease and its response to treatment is more predictable. The stage of the disease is also critical, in terms of both the initial response and the long-term response: patients in chronic phase disease have better outcomes with all of the TKIs than patients with accelerated phase or blast crisis disease.The diagnosis of CML typically requires a bone marrow exam to confirm the stage of the disease, followed by cytogenetic and molecular analysis to confirm not only the presence of the 9;22 translocation that gives rise to the Philadelphia chromosome but also to assess for other clonal cytogenetic abnormalities that may be present at baseline. These are the prerequisite steps to confirm the diagnosis. Because of the presence of the Bcr-Abl transcripts, quantitative PCR can be used later to monitor levels of residual disease over the course of treatment.

About one third of patients with CML will have no symptoms at the time of initial diagnosis. Others may have symptoms related to splenomegaly or, sometimes, anemia. Some patients may be hyperuricemic because of the hypermetabolic activity of the disease. Consequently, initiation of supportive care, which may include treatment with allopurinol and an attempt to normalize renal function, is important before the treatment of CML-related hyperleukocytosis begins.

Medscape: Please discuss the standard treatment for a patient with CML.

Dr. Larson: The standard initial treatment for the last 10 years has been to use imatinib at a dose of 400 mg/day.[10] Data from recent randomized trials indicate that the response to imatinib at 800 mg/day (ie, 400 mg twice a day) may produce a faster initial response,[11] but over the longer term of 9-12 months, the higher dose does not appear to be more effective than the 400 mg/day dose. This may be, in part, because a dose of 800 mg/day can produce more side effects, and many patients are not able to tolerate the double dose of imatinib as initial therapy.Clinicians treating patients with CML need to be familiar with management guidelines. The first were published by the European LeukemiaNet in Blood in 2006 and then revised more recently and published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2009. In addition, the European Society of Medical Oncology's Clinical Practice Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of CML were issued in 2010.[14

Both of these guidelines establish a series of mileposts, based on the experience to date with standard doses of imatinib, that should be reached by patients to indicate an optimal response. These include an early hematologic response, followed by partial and complete cytogenetic responses, and eventually major molecular response. These terms have now been clearly defined, and it is suggested that if patients are not achieving those mileposts on a standard dose of imatinib, then treatment should be switched. A switch should occur before patients show evidence of treatment failure with disease progression or lack of response.

The likely long-term outcome for an individual patient with chronic phase CML will depend on whether he or she has achieved certain levels of response by 3, 6, 12, and 18 months after starting on imatinib. Previously, the only options available for patients not responding to imatinib included increasing the dose of imatinib from 400 mg/day to 600 or 800 mg/day or, in some cases, considering an allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant.

More options now exist, following the approval over the past couple of years of the second-generation TKIs (ie, dasatinib and nilotinib) for patients who have either not tolerated imatinib or who have failed to achieve or maintain a response to imatinib. These second-generation TKIs are entering the treatment paradigm earlier, and additional TKIs are in development.

Medscape: Some of the major news out of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2010 meeting centered on nilotinib and dasatinib. Can you describe those trials and their implications?

Dr. Larson: There were 2 phase 3 trials conducted in first-line chronic phase CML -- ENESTnd, which compared nilotinib with imatinib, and DASISION, which compared dasatinib with imatinib -- that were reported on at ASCO[5,6] and then published in the New England Journal of Medicine in June 2010.[8,9]

In the ENESTnd trial,[8] Saglio and colleagues evaluated the efficacy and safety of nilotinib vs imatinib in 846 patients randomized to receive nilotinib, either at 300 mg twice daily or 400 mg twice daily, or imatinib at a dose of 400 mg once daily.

The dose of imatinib could be escalated to 800 mg/day according to protocol guidelines for treatment response. All of the patients were older than 18 years, and they had good performance status and adequate organ function. Importantly, a baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) was required, and patients were eligible only if their corrected QT interval on ECG was less than 450 milliseconds. The reason for the ECG is that these TKIs appear to have the potential to prolong the QT interval. Consequently, patients had to have a QTc interval that was well within the safe limit in order to enroll in the trial.

This study was a rigorous assessment of the efficacy and tolerability of these drugs. All of the major analyses were performed according to the principle of intention-to-treat. A major molecular response, the primary endpoint, was defined as a BCR-ABL transcript level of less than 0.1% on the International Scale.