د. حسين محمد جمعة

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنةالبورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2012

Diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adultsand children: summary of updated NICE guidance

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2012

Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder characterised by recurring epileptic seizures; it is not a single diagnosis but is asymptom with many underlying causes, more accurately termed

the epilepsies. Antiepileptic drugs(AEDs) to prevent recurrence of seizures form the mainstay of treatment.

Diagnosis can be challenging, making accurate prevalence estimates difficult.

With a prevalence of active epilepsy of 5-10 cases per 1000,epilepsy has been estimated to affect between 362 000 and 415000 people in England, but with a further 5-30% (up to another 124 500 people) misdiagnosed with epilepsy.

Consequently, it is a physician or paediatrician with expertise in epilepsy who should diagnose and manage the condition.

The 2004 guideline from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence on the management of the epilepsies in adults and children was

recently partially updated with regard to drug management.

This article summarises the main recommendations of the updated version; new recommendations are indicated in parentheses.

Recommendations

NICE recommendations are based on the best available evidence and explicit consideration of cost effectiveness. When minimal evidence is available, recommendations are based on theGuideline Development Group’s experience and opinion of what constitutes good practice.

Evidence levels for the recommendations are given in italic in square brackets.

After a first seizure • Children, young people, and adults presenting to an emergency department after a suspected seizure should be screened initially for epilepsy. This should be done by an adult or paediatric physician with onward referral to aspecialist when an epileptic seizure is suspected or there is diagnostic doubt.

(A specialist is defined in the guidance as either a “medical practitioner with training and expertise in epilepsy” (for adults) or a “paediatrician with training and expertise in epilepsy” (for children and young people).

[Based on the experience and opinion of the Guideline Development Group (GDG)]

Diagnosis

All children, young people, and adults with suspectedseizure of recent onsetshould be seen urgently (within

Two weeks) by a specialist.

This is to ensure precise and early

diagnosis and start of therapy as appropriate to their

needs.

[Based on evidence from descriptive studies]

A definite diagnosis of epilepsy may not be possible. If the diagnosis cannot be clearly established, consider further investigations and/or referral to a tertiary epilepsy specialist.

Always arrange follow-up.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Investigations

Children, young people, and adults needingelectroencephalography should have the test performed soon (within four weeks) after it has been requested.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG and evidence from descriptive studies]

Do 12 lead electrocardiography in adults with suspected epilepsy.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GDGand evidence from descriptive studies]

In children and young people, consider 12 lead

electrocardiography in cases of diagnostic uncertainty.

Magnetic resonance imaging should be the imaging

investigation of choice in everyone with epilepsy. [Basedon evidence from descriptive studies]

Magnetic resonance imaging is particularly important in

those:

1- Who develop epilepsy before the age of 2 years or in

Adulthood.

2- Who have any suggestion of a focal onset on history,

examination, or electroencephalography (unless there is

clear evidence of benign focal epilepsy)

3- In whom seizures continue despite first line medication.

Children, young people, and adults needing magnetic

resonance imaging should have it done soon. [Based on

the experience and opinion of the GDG].

General information about drug treatment

Adopt a consulting style that enables the child, youngperson, or adult with epilepsy, and their family and/or

carers as appropriate, to participate as partners in all

decisions about their healthcare and take fully into account their race, culture, and any specific needs.

Everyone with epilepsy should have a comprehensive care plan that is agreed between the person, their family and/or carers as appropriate, and primary and secondary care providers.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG and evidence from descriptive studies]

Individualise the strategy for AED treatment according to the seizure type; epilepsy syndrome; comedication and comorbidity; the lifestyle of the child, young person, or adult; and the preferences of the person, their family, and/or carers as appropriate. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

If using carbamazepine, offer controlled release

preparations. (New recommendation.) [Based on the

experience and opinion of the GDG]

Forspecific advice for women and girls of childbearing potential about AEDs, including sodium valproate,see later in this article.

Starting drug treatment

When possible, offer an AED chosen on the basis of the presenting epilepsy syndrome. If the epilepsy syndrome is not clear at presentation, base the decision on the presentingseizure type(s). (New recommendation.) [Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG].

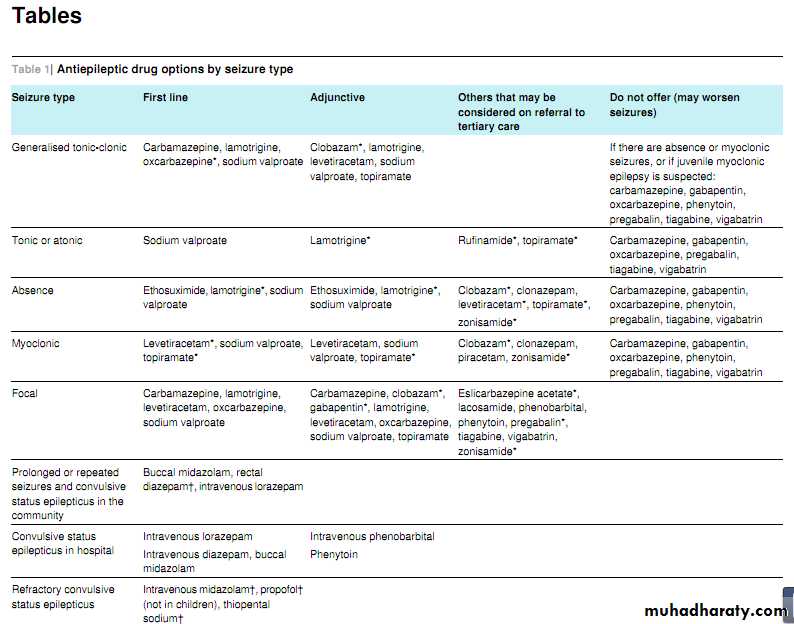

Tables 1⇓ and 2⇓ summarise the different drug options according to seizure type and syndrome.

First line treatment for newly diagnosed focal

Seizures

Offer carbamazepine or lamotrigine as first line treatment.(New recommendation.) [Based on moderate to very low quality evidence from randomised controlled trials and on cost effectiveness evidence]

Levetiracetam is not cost effective .

First line treatment for newly diagnosed

generalised tonic-clonic seizures

Offer sodium valproate as first line treatment. (New recommendation.) [Based on low to very low quality evidence from randomised controlled trials, cost effectiveness evidence, and experience and opinion of the GDG] .

If sodium valproate is unsuitable, offer lamotrigine.

Adjunctive treatment for refractory focal seizures

If first line treatments are ineffective or not tolerated, offer carbamazepine, clobazam, gabapentin, lamotrigine,levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, sodium valproate, or topiramate as adjunctive treatment . (New recommendation.) [Based on moderate to very low quality evidence from randomised controlled trials, cost effectiveness evidence, and experience and opinion of the GDG] .If adjunctive treatment is ineffective or not tolerated,

discuss with, or refer to, a tertiary epilepsy specialist, who may consider other AEDs: eslicarbazepine acetate, lacosamide, phenobarbital, phenytoin, pregabalin, tiagabine, vigabatrin, and zonisamide. Carefully balance the risks and benefits when using vigabatrin because of the risk of an irreversible effect on visual fields. (New recommendation.)[Based on moderate to very low quality evidence from randomised controlled trials, cost effectiveness evidence, and experience and opinion of the GDG]

First line treatment for newly diagnosed

generalised tonic-clonic seizuresOffer sodium valproate as first line treatment. (New recommendation.) [Based on low to very low quality evidence from randomised controlled trials, cost effectiveness evidence, and experience and opinion of the GDG] .

If sodium valproate is unsuitable, offer lamotrigine.

If the person has myoclonic seizures or is suspected of having juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, be aware that lamotrigine may exacerbate myoclonic seizures. (New recommendation.)

[Based on low to very low quality evidence from randomised controlled trials, cost effectiveness evidence and experience, and opinion of the GDG].

Consider carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine, but be aware of the risk of exacerbating myoclonic or absence seizures.

(New recommendation.) [Based on low to very low quality evidence from randomised controlled trials and experience and opinion of the GDG]

Adjunctive treatment for generalised tonic-clonic seizures

If first line treatments are ineffective or not tolerated, offer clobazam, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, sodium valproate,or topiramate as adjunctive treatment. (Newrecommendation.) [Based on high to very low quality

evidence from randomised controlled trials and cost

effectiveness evidence]

If myoclonic seizures are absent or if juvenile myoclonic epilepsy is suspected, do not offer carbamazepine, gabapentin, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, pregabalin,tiagabine, or vigabatrin. (New recommendation.) [Based on experience and opinion of the GDG]

Continuation of drug treatment

Maintain a high level of vigilance for the emergence ofadverse effects associated with the drug treatment (such as reduced bone density) and neuropsychiatric problems (as there is a small risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviour;available data suggest that this risk applies to all AEDs and may occur as early as a week after starting treatment (New recommendation.) [Based on experience and opinion of the GDG]

Ketogenic diet

Refer children and young people with epilepsy whose seizures have not responded to appropriate AEDs to atertiary paediatric epilepsy specialist for consideration of introducing a ketogenic diet. (New recommendation) [Based on low to very low quality evidence from randomised controlled trials and experience and opinion of the GDG]Prolonged or repeated seizures and convulsive status epilepticus

Only prescribe buccal midazolam or rectal diazepam for use in the community for those who have had a previous episode of prolonged or serial convulsive seizures. (New recommendation.) [Based on experience and opinion of the GDG]

Administer buccal midazolam as first line treatment in the community.

Administer rectal diazepam if preferred or ifbuccal midazolam is not available.

If intravenous access is already established and resuscitation facilities are available, administer intravenous lorazepam. (New recommendation.) [Based on high to very low quality evidence from randomised controlled trials]

Advice for women and girls with epilepsy

Discuss with women and girls of childbearing potential (including young girls who are likely to need to continuetreatment into their childbearing years)—and their parentsand/or carers if appropriate—the risk of AEDs causing malformations and possible neurodevelopmental impairments in an unborn child. Assess the risks and benefits of treatment with individual drugs.

Data are limited on the risks to the unborn child that are associated with newer drugs. Specifically discuss the risk to the unborn child of continued use of sodium valproate, being aware that higher doses ofsodium valproate (>800 mg a day) and multidrug treatment, particularly with sodium valproate, are associated with greater risk. (New recommendation.) [Based on low to very low quality evidence from systematic reviews of cohort studies and data registries, and experience and opinion of the GDG]

Discuss with women and girls taking lamotrigine the

evidence that the simultaneous use of any oestrogen basedcontraceptive can result in a significant reduction in lamotrigine levels and loss of seizure control.

When starting or stopping these contraceptives, the dose of lamotrigine may need adjustment.

(New recommendation.) [Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

People with learning disabilities

Ensure adequate time for consultation to achieve effective management of epilepsy.(New recommendation.) [Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Do not discriminate against people with learning

disabilities; offer the same services, investigations, and

treatments to them as to the general population. (New

recommendation.) [Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Older people with epilepsy

Do not discriminate against older people; offer the same

services, investigations, and treatments to them as to the

general population.

(New recommendation.) [Based on the

experience and opinion of the GDG]

Pay particular attention to pharmacokinetic and

pharmacodynamic problems with multidrug treatment and comorbidity. Consider using lower doses of AEDs, and, if using carbamazepine, offer controlled releasecarbamazepine preparations. (New recommendation.)

[Based on moderate to very low quality evidence from

randomised controlled trials]

Review and referral

Provide a regular structured review to everyone withepilepsy. In children and young people, conduct the review at least yearly (but this may be reduced to between 3 and 12 months by arrangement) by a specialist. In adults, conduct the review at least yearly by a generalist or aspecialist, depending on how well the epilepsy is controlled and/or the presence of specific lifestyle problems (such as sleep pattern, alcohol consumption). [Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG and on evidence from

a Cochrane review ofrandomised trials and evidence from surveys and audits]

Overcoming barriers

The Guideline Development Group was aware of concerns about prescribing sodium valproate to girls and women of childbearing age. The updated recommendations offer alternative prescribing options for this group and also provide additional relevant information when considering prescribing antiepileptic drugs to women of childbearing age.The group also wished to ensure that people with learning disabilities and older people had optimal treatment and had the same opportunities as other adults to access treatments and specialist epilepsy services; the group expressed concern that this is not necessarily current practice.

Further information on the guidance

The original NICE guideline on epilepsy was published in 2004, but since then five more antiepileptic drugs have become licensed for use in the United Kingdom to treat epilepsy. The updated 2012 guideline focuses on drug management and on recommendations for seizure type, but also, even more importantly, on epilepsy syndrome, emphasising the need to diagnose the syndrome when possible.It provides first line and adjunctive guidance on drug treatment, including clear guidance on which AEDs not to offer for specific seizure types and

syndromes. Previous recommendations (which were not reviewed for this update) otherwise remain unchanged, and still stand for implementation.

Cost effectiveness analysis for first line and adjunctive drug treatment for newly diagnosed and refractory focal seizures in children and adults .An economic model was developed to compare the cost effectiveness of seven different AEDs licensed for treatment of adults with newly diagnosed focal seizures. Of these seven, lamotrigine was the most cost effective in the base case, but results of sensitivity analyses around cost showed that carbamazepine may also be cost effective.

For patients in whom these drugs were considered unsuitable, sodium valproate and oxcarbazepine were likely to represent the most cost effective alternatives. Results of modelling showed that there is substantial uncertainty around the cost effectiveness of levetiracetam, driven by a limited clinical evidence base and questions about its future cost.

Lamotrigine and carbamazepine consistently represented better value for money than levetiracetam across a range of potential cost reductions.

Levetiracetam became more cost effective than sodium valproate and oxcarbazepine only when it could be acquired for less than 50% of its June 2011 unit cost. An economic model was developed to assess the AEDs licensed for treatment of children with newly

diagnosed focal seizures, but given the extremely limited evidence base, conclusions were subject to considerable uncertainty.

Another economic model was developed to compare the cost effectiveness of 11 different AEDs licensed for treatment of adults with refractory focal seizures. Results indicated that adjunctive therapy with some of these 11 drugs was cost effective, but a conclusion about which to prescribe was highly uncertain and was dependent on a patient’s previous treatments. Lamotrigine and oxcarbazepine were the most cost effective adjunctive therapies in the base case.

In key sensitivity analyses around unit costs, effect estimates, and assumptions about which

treatments have previously been trialled, adjunctive therapy with gabapentin, topiramate, and levetiracetam emerged as potentially cost effective. Treatment with newer AEDs—including eslicarbazepine acetate, lacosamide, pregabalin, tiagabine, and zonisamide—was never found to be cost effective.

A further analysis, which used alternative costs and utility estimates, was conducted to estimate the cost effectiveness of adjunctive AEDs licensed for the treatment of children. Results were broadly similar to those found in the analysis for an adult population and were also sensitive to variation of cost and previous treatment.

Cost effectiveness analysis for adjunctive drug treatment for refractory generalised tonic-clonic seizures in adults An economic model was developed to compare the cost effectiveness of three different AEDs licensed for treatment of individuals with

refractory generalised tonic-clonic seizures.

Of these three, lamotrigine was found to be the most cost effective in the base case, and this finding was robust in all sensitivity analyses conducted.

Levetiracetam was the most cost effective AED if lamotrigine had been trialled previously or was unsuitable. Topiramate, the only other adjunctive AED for which there were clinical data, was cost effective only when other options such as lamotrigine and levetiracetam were considered unsuitable.

*At the time of publication of the main NICE guidance (January 2012), this drug did not have UK marketing authorisation for this indication and/or population.Informed consent should be obtained and documented.

†At the time of publication of the main NICE guidance (January 2012), this drug did not have UK marketing authorisation for this indication and/or population. Informed consent should be obtained and documented in line with normal standards in emergency care.

Newer drugs for focal epilepsy in adult

BMJ 26 January 2012This is one of a series of occasional articles on therapeutics for common or serious conditions, covering new drugs and old drugs with important new indications or concerns. The series advisers are Robin Ferner, honorary professor of clinical pharmacology, University of Birmingham and Birmingham City Hospital, and Philip Routledge, professor of clinical pharmacology, Cardiff University. To suggest a topic for this series, please email us at practice@bmj.com.

A 28 year old woman sees her general practitioner after experiencing what sounds like a convulsion without any apparent provoking factor. Over the past month she has also had “blank spells” during which her husband noticed her to be unresponsive.

Her general practitionersuspectsshe may have developed focal epilepsy and refers her to an epilepsy specialist.

The specialist elicits from the patient and her husband additional features in the history that are highly compatible with seizures arising from the temporal lobe (lip smacking, ipsilateral motor automatism,and contralateral dystonia) and confirmsthe diagnosis by finding focal epileptiform discharges on electroencephalography and cortical dysplasia in the left temporal lobe on brain imaging.

What are the newer antiepileptic drugs?

Epilepsy is resistant to drug treatment in a third of patients.Driven by this high prevalence of drug resistance, 12 agents have been developed to treat adult epilepsy since the late 1980s.

These are often referred to collectively as the “newer”

antiepileptic drugs—that is, newer than the established drugs,such as phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, sodium valproate, and several benzodiazepines, with phenobarbital having been around for 100 years.

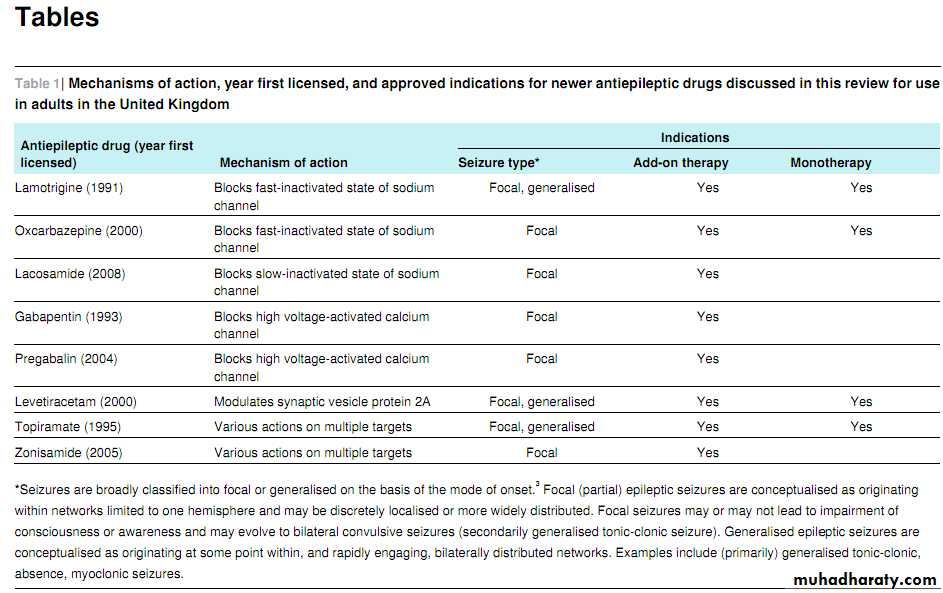

In this article we will review

the clinical use of (in chronological order of approval in the United Kingdom) lamotrigine, gabapentin, topiramate, oxcarbazepine, levetiracetam, pregabalin, zonisamide, and lacosamide (table 1⇓). We will not discuss the other newer AEDs tiagabine and vigabatrin because they are rarely used for focal epilepsy in adults (owing to efficacy and safety concerns respectively) or eslicarbazepine acetate and retigabine, which have only recently been approved and for which clinical experience is therefore limited.How well do the newer antiepileptic drugs work?

Add-on therapyTo obtain licensing approval as add-on therapy, all AEDs have to show superior efficacy compared with placebo in double blind randomised controlled trials. In regulatory studies for AEDs, the primary efficacy measure is statistical significance against placebo for responder rate in Europe (defined as a ≥50% reduction in seizure frequency) and median reduction in seizure frequency in the United States.

A recent meta-analysis that evaluated the clinical effectiveness and tolerability of the newer AEDs included 62 placebo controlled studies in children and

adults in terms of responder and withdrawal rates (table 2⇓).

Owing to methodological heterogeneity—such as in the range of dosagestested and of treatment durations(8-26 weeks)—and the small differences found, caution is needed in drawing comparisons between these drugs. In addition, the clinical relevance of the responder rate as a useful clinical end point remains questionable.

The recent consensus from the International League Against Epilepsy proposes that atreatment’s success should be defined by sustained freedom from seizures, as that is the only efficacy outcome consistently associated with improved quality of life (and in the UK the only efficacy outcome that allows a patient to drive legally). Using this measure, another meta-analysis showed that the overall weighted pooled-risk difference in favour of the newer AEDs compared with placebo for freedom from seizures during the limited study periods was only 6% (95% confidence interval 4% to 8%; number needed to treat in terms of freedom from seizures,).

Monotherapy

Several of the newer AEDs have shown efficacy similar to that of the older drugs (mostly carbamazepine), and sometimes similar to that of each other, for the treatment of new onset focal epilepsy in adults in head to head monotherapy trials and have been approved for this indication in the UK and other European countries. These approved drugs include levetiracetam,

lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, and topiramate and in some countries gabapentin.

The SANAD study found that gabapentin had

significantly inferior efficacy compared with carbamazepine,and most experts do not recommend gabapentin as initial monotherapy.How safe are the newer antiepileptic drugs?

All AEDs are associated with a range of adverse effects, the main reason for withdrawal in regulatory trials.5 Many adverse effects were detected only during postmarketing surveillance,and their long term adverse effects (such as on bone health) are unknown.

Idiosyncratic reactions

Such reactions are unpredictable adverse effects independent of dosage.The most common of these is rash, which develops in 3-5% of patients taking lamotrigine, zonisamide, or oxcarbazepine but in <1% of those taking topiramate,levetiracetam, gabapentin, or pregabalin.

Lamotrigine and oxcarbazepine can rarely lead to Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Other rare idiosyncratic reactions include hepatitis, pancreatitis, and blood dyscrasias.

Ophthalmic effects Rare cases of acute angle-closure glaucoma and myopia have been reported with topiramate.

Neurotoxicity .Typical dose related symptoms including nausea, diplopia,dizziness, headache, tiredness,somnolence,sedation, and ataxia

can occur with all AEDs.

Renal calculi

Topiramate and zonisamide carry a small (1%) risk of symptomatic renal calculi as both drugs inhibit carbonic anhydrase.Cardiac effects

Minor prolongation in the PR interval has been observed in clinical studies with lacosamide.

Psychiatric effects

Topiramate is associated with anorexia, weight loss, word finding difficulties, and neuropsychiatric complications.

Behavioural problems, such as agitation, aggression, hostility,psychosis, anxiety, and depression, have been reported in patients treated with levetiracetam. Zonisamide can also produce or exacerbate psychiatric comorbidities, particularly depression.

The US Food and Drug Administration analysed data from 199 placebo controlled trials of 11 AEDs and found an increase in risk of suicidal behaviour or ideation among patients receiving

them (0.43%) compared with those receiving placebo (0.22%).

A community based case-control study in treated epilepsy documented increased risk ofsuicidal behaviour associated with some newer AEDs (such as topiramate, levetiracetam) only in patients with a high risk of depression.

Teratogenicity

Recent data from EURAP, the largest international prospective cohortstudy of 3909 pregnancies, reported that in utero exposureto lamotrigine monotherapy was associated with an overall,dose dependent rate of major fetal malformation at 1 year of age that ranged from 2% (<300 mg/day) to 4.5% (≥300 mg/day).

This was less than that with carbamazepine (3.4% to 8.7%), phenobarbital, (5.4% to 13.7%) and particularly sodium valproate (5.6% to 24.2%).

The UK pregnancy register reported a rate of major fetal malformation for untreated women with epilepsy (n=239) of 3.5% (95% confidence interval 1.8% to

6.8%). Children exposed to lamotrigine in utero had similar IQs at age 3 years to those exposed to phenytoin and carbamazepine, which was around 10 percentage points higher than those taking high dose sodium valproate.

Data from the US and UK pregnancy registries indicate an increased risk of oral cleftsin infants exposed to topiramate monotherapy during the first trimester.

Sufficient data for other newer AEDs are

lacking, although preliminary experience from the UK

pregnancy registry has suggested a low risk of teratogenicity with levetiracetam.

What are the precautions?

Precautions relate to potential adverse effects as discussed above. Examples are outlined as follows.

Rash

Closely monitor patients with a history of allergic rash when introducing an AED as they have an approximate fivefold increased risk of developing another rash.

Avoid oxcarbazepine

in patients with a history of rash induced by carbamazepine because of a cross sensitivity rate between these drugs of 25-31%.

Cardiac problems

For patients with a history of cardiac problems, including conduction block, taking drugs known to prolong the PR interval, and for those aged over 65, use lacosamide cautiously and perform electrocardiography before starting treatment and after titration to optimal dosage.History of psychiatric illness Avoid topiramate, levetiracetam, and zonisamide, or, if essential,

use these cautiously.

History of renal calculi

Avoid topiramate and zonisamide as they inhibit carbonicanhydrase; advise all patients taking these drugs to avoid dehydration.

Renal impairment

For patients with renal impairment prescribe lower doses of gabapentin, levetiracetam, and pregabalin as these are predominantly excreted unchanged in the urine.

Interaction with oral contraceptives As oxcarbazepine and topiramate (at daily doses above 200 mg)

selectively induce the breakdown of the oestrogenic component of oral contraception.

patients taking oral contraception need formulations with higher doses (50 μg) of oestrogen, with subsequent adjustment of hormones depending on any breakthrough bleeding; other contraceptive measures must be taken until the menstrual pattern has been stable for at least three months. As the oestrogenic component of oral contraception significantly increases the metabolism of lamotrigine, the dosage of lamotrigine may need adjustment when starting combined oral contraception (to maintain seizure control) and when stopping the pill (to minimise adverse effects of lamotrigine).

Pregnancy

Limited data are available on the teratogenic risk of the newer AEDs. Counsel women of childbearing potential on pregnancy matters early.

Advise them to plan pregnancy, so that any changes to their regimen of AED treatment can be made before conception (because teratogenesis may occur early in the first trimester).

Treatment with AEDs should be continued during pregnancy on the basis that seizures, especially convulsive seizures, are more harmful to the mother and fetus than are the drugs themselves; however, treatment should be tapered to aminimal effective dose before pregnancy, if possible to a single AED.

Supplemental folic acid is advised (≥400 μg daily) before conception and during pregnancy to reduce the risk of major congenital malformation.

Offer prenatal diagnosis using targeted fetal ultrasonography to detect any major structural

abnormalities.

After delivery, encourage all mothers to breast feed their babies. If the AED dose, particularly that of lamotrigine, has been increased during pregnancy, consider areduction in dosage after delivery.

Breast feeding

Lamotrigine can accumulate in the breastfed baby because of slow elimination.However, few data relate to the other newer AEDs.

As a general rule, if the baby is noted to be drowsy or sedated, breast feeding should be alternated with bottle feeding or discontinued.

How are the newer antiepileptic drugs

taken and monitored?All the newer AEDs discussed in this article are taken orally.

Oxcarbazepine and levetiracetam are available in liquid formulations. Lacosamide is also available as a syrup and by intravenous injection. An intravenous formulation of levetiracetam has been licensed in Europe for patients aged ≥4 years when oral administration is temporarily not feasible.

In general, start newer AEDs at low dosage, with increments over several weeks to establish an effective and tolerable regimen.

Some agents, such as gabapentin and levetiracetam,

can be started at effective doses with or without rapid titration,whereas others, such as lamotrigine and topiramate, require slow titration to reduce the risk of rash and cognitive impairment, respectively. Slow titration will also facilitate the development of tolerance to sedation and will ensure early detection of potentially serious idiosyncratic reactions.Once the target dosage has been reached, adjust the dose further on the basis of seizure control and tolerability.

Routine measurement of serum concentrations of the newer AEDsis not recommended (and not available in most clinical settings), as they do not correlate well with efficacy or side effects.

However,serum concentrations of lamotrigine fall dramatically during pregnancy, in patients who have recently started taking an oral contraceptive containing oestrogen, and in women just before the onset of the menses.

Lamotrigine monitoring is particularly helpful in guiding dosing during pregnancy.

Such monitoring is not available routinely across the UK and is best performed with advice from an epilepsy specialist. Arguably,however, lamotrigine concentrationsshould be measured before conception, regularly throughout pregnancy, and in the puerperium.

How cost effective are the newer antiepileptic drugs?

Whether the better tolerability and interaction profile of newer AEDs are worth the higher price has been much debated. High quality cost effectiveness studies are lacking. The guidelinesfrom the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) included cost utility analyses of AEDs and found lamotrigine to be the most cost effective monotherapy (although carbamazepine may be as cost effective).

How do the newer antiepileptic drugs

compare with the established ones?Given the limited number of comparative studies, AED

treatment for the individual patient is not based entirely on these and depends also on the patient’s age, weight, sex, comorbidities, and perceived differences in adverse effects, propensity for interactions, and cost.

Owing to the absence of adequate evidence, judgments about treatment choice (in an attempt to be rational) are based on what we think we know

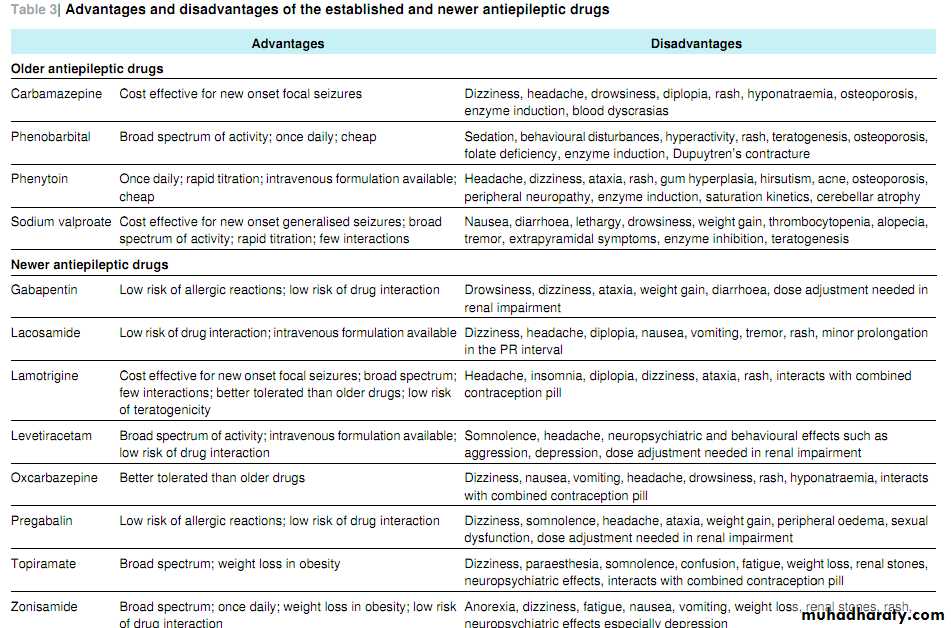

about these other factors. Table 3⇓ lists some advantages and disadvantages of the established and newer AEDs.

Choice of drug in newly diagnosed epilepsy

Based on a systematic review and consideration of clinical benefits, harms, and cost effectiveness, the updated NICE guidelines recommend offering carbamazepine or lamotrigine asfirst line treatment to children, young people, and adults with

newly diagnosed focal seizures; if these are unsuitable or not tolerated, NICE recommends levetiracetam (if its acquisition cost falls to at least 50% of the value at June 2011), oxcarbazepine, or sodium valproate.

Evidence, supporting only carbamazepine,

phenytoin, and valproic acid as initial monotherapy for partial onset seizures in adults and lamotrigine and gabapentin for older people.On the basis of the double blind, randomised

monotherapy study of levetiracetam versus extended release carbamazepine in newly diagnosed epilepsy, which fulfilled the strict criteria of the International League against Epilepsy, levetiracetam can also be recommended for this indication.

Choice of drug in uncontrolled epilepsy

As very few head to head comparisons of new AEDs exist for the treatment of drug resistant epilepsy, choice remains largely empirical. The increasing number of available agents has encouraged consideration of their different mechanisms of action(table 1⇓) in optimising their efficacy in combination. The broad spectrum AEDs levetiracetam, topiramate, and zonisamide, which have multiple mechanisms of action, are often chosen in drug resistant epilepsy.

Our case scenario Treatment with AEDs is indicated for our patient with recurrent focal seizures, the latest of which seem to have developed into

a secondarily generalised seizure (epileptic seizure with focal onset and subsequent bilateral convulsion). On the basis of this review and in line with NICE guidance, given the patient’s childbearing potential, the drug of choice would be lamotrigine,preferably maintained at <300 mg/day.

Ideally, monitor the concentration before conception, during pregnancy, and in the puerperium. We do not recommend carbamazepine for her because of its comparatively higher risk of fetal malformation (when the dose is ≥400 mg/day) and enzyme induction of the oestrogenic component of her oral contraception. Levetiracetam can also be considered because it is effective as controlled release carbamazepine and preliminary data suggest a low risk of teratogenicity, although NICE asserts that it is not as cost effective as lamotrigine at June 2011 unit costs.

Tips for patients

Drug treatment aims at preventing the development and spread of seizures (the electrical consequence of an underlying process in the brain) but does not affect the underlying cause of the epilepsyKeep a diary of any seizures and side effects you have experienced and discuss the record with your general practitioner or epilepsy specialist during consultations.

Discuss the common problems associated with your treatment with your general practitioner before starting any new drug.

If you think you are experiencing a side effect with your epilepsy treatment, discuss this as soon as possible with your general practitioner or epilepsy specialist .If you are a woman you should seek advice on contraception to ensure that the epilepsy treatment does not interfere with your oral contraception and request referral to an epilepsy specialist if you are planning a pregnancy.

Health problems that arise months or years after taking an unchanged treatment schedule are unlikely to be the result of the antiepileptic drugs but should be discussed with your doctor as they may affect your epilepsy treatment.

Adding another medicine can sometimes interfere with the epilepsy drugs, producing side effects or reducing the efficacy of these drugs and thus worsening seizure control. Check this specifically with your doctor when he or she recommends starting you on any new drug

Very rarely an epileptic seizure can affect the function of the heart, lungs, or brain, resulting in sudden death, and so taking the antiepileptic drugs is essential.

Tips for general practitioners

Refer patients with suspected epilepsy to a specialist in epilepsy care for diagnosis, investigation, and treatmentIf problems arise, seek advice from the appropriate neurologist or local epilepsy specialist nurse

Refer patients planning a pregnancy to an epilepsy specialist for advice, optimisation of the antiepileptic drug regimen, and initiation of folic acid

When introducing adjunctive treatment in a patient with drug resistant epilepsy it may be necessary to reduce the dose of one of the other drugs, particularly if this is being taken at a high dose, to facilitate optimal tolerability.

If a clinical problem occurs after an antiepileptic drug monotherapy or multidrug regimen has been stable for some years, the problem is unlikely to be caused by the antiepileptic drugs.

Routine therapeutic drug monitoring of antiepileptic drugs is not necessary. Use monitoring only to ask a clinical question, such as whether the patient is complying with the treatment.

If a patient is considering stopping treatment, advise him or her to discuss the risks with an epilepsy specialist before finalising the decision.

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

BMJ 26 January 2012I was 27 years old, had been married about a year, and was living in Inverness when I was diagnosed with epilepsy. I had moved to the area when we got married but didn’t know anyone, and it was all very new to me. I was working in a school for children with special needs, which I loved, and was just beginning to find my feet and gain a little confidence.

Although I had experienced a seizure when I was about 14, it was investigated with electroencephalography and doctors concluded that it was not epilepsy, highly likely to be a one off, and may even have been a reaction to a dose of antisickness medication following a minor knee operation.

Several months into married life, I began to have more and more frequent jerks, predominantly in my right arm. I ignored them for a while but they became too regular and too disruptive to do so for long. I

couldn’t serve up food on to plates without spilling it and hot drinks were also dangerous. I recalled the jerks from stressful situations during my university days, but I had never put two and two together.

Restriction I have never really been one to talk about my epilepsy; I guess at times it has been my way of coping. I don’t think I have been in denial but I just talk myself through things at my own pace over and over again in my head, coming to terms with the constraintsthe condition imposes on me.When I was diagnosed, I remember coming home from the hospital after seeing the consultant and being devastated because I would no longer be able to drive. My husband, John, worked away for two weeks at a time so I was going to have to sort out lifts for work and in an instant I felt like all my independence had been taken away from me. It wasn’t so much the epilepsy as its practical repercussions.

I don’t remember being given any information at the time about epilepsy in general. We weren’t fortunate enough to have an epilepsy nurse specialist in Inverness ten years ago, so there really wasn’t any support for me or my husband that we knew of. Since then I have used the Epilepsy Action website (www.epilepsy.org.uk), watched related television programmes, and listened to radio programmes, and I guess I have just had more time to come to terms with my diagnosis.

First and second pregnancies .A very low dose of sodium valproate controlled my myoclonic seizures for my first year but by then I was thinking of starting

a family and so was taken off the drug by my general

practitioner. I remained free of seizures throughout my first pregnancy but went back on to sodium valproate when my daughter was three months old because the seizures recurred.

Ididn’t appear to suffer from any side effects but more drug changes were inevitable as I was planning another pregnancy.

Also, I had my first tonic-clonic seizure a year or so later.

Planning was the name of the game and so I was trialled on levetiracetam by yet another consultant. The dose for this increased dramatically throughout my pregnancy. I think I was on the highest dose the drug was licensed for—and still it did not control the seizures.

With hindsight, I don’t think anything would have controlled them, but looking back I can see how I

became a different person. I lost a lot of confidence and became anxious about everything, to the point of really not wanting to do anything or go anywhere. That was just not like me. I was tired all the time and just wanted to sleep, but I was the sole carer for two weeks each month. Eventually we had to move closer to my family and friends.We managed to find two friends

in particular who were willing to stay overnight and make sure I was OK with the two little ones when John was away working.

Support and progress

Moving has been frustrating at times. First, we went from Inverness to Aberdeen where we received excellent care and advice with research projects on the go and nurse specialists available when I needed them. They were particularly supportive during my second pregnancy (a 24 hour answer phone wasavailable) as drug treatment during pregnancy was a field they were researching. It made me feel like somebody knew what they were talking about and that gave me a feeling of security.

We then moved to Cardiff where the most frustrating part was the delay in seeing a consultant; apparently my notestook almost nine months to appear. My general practitioner was great in understanding my situation and frustrations, helping me to balance it all with being careful as a busy mum. After my last

change in medication we would speak over the phone to change doses as requested by the consultant. This saved her surgery time and saved me finding time to go to the surgery without the children in tow.

My job just now is at home with the children and it gives me so much flexibility in keeping my epilepsy under control. If I am tired, I can do less about the house or go to bed for an hour when the little one is at nursery and my seizures have been far

less frequent. I had been having myoclonic jerks up to five or six times a day about a year ago (although this may have been a side effect of the drugs), but I haven’t had any since being put on zonisamide. My last tonic-clonic seizure was in October 2010. It sounds like a cliché but I do feel I am getting my life

and my old self back.

Reflection .What do I know now that I wish I had been told at the time?

That there is no quick fix. Everyone is different, I know, but personally I like to be told things straight. I might not like what I hear initially, but I am not someone who finds it easy to read between the lines. I wish someone could have told me at the beginning of my journey with epilepsy that there is often no quick and easy cure.It is often about “playing around” with drugs until doctors find the ones that suit you. Even then, there

is no guarantee that you can remain on those drugs for the rest of your life. Depending on your type of epilepsy it may get worse at different stages in your life; it may not, but be as prepared for it as possible.

A doctor’s perspective

450 000 people are estimated to have epilepsy within the UK and a further one in twenty people has a seizure in their life time. Epilepsy remains poorly understood (even within some medical circles) despite its high prevalence and its long term nature, and stigma is common.To many people a bigger cause of isolation, stress, and stigma than the diagnosis itself is the ineligibility to drive that accompanies epilepsy.There are only so many places a free bus pass can get you to in rural Scotland—particularly when trying to navigate a pram through the public transport system.

Nicola’s story of a delayed diagnosis of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy is very typical, yet she has had her own difficulties to face. Myoclonic

jerks are often not recognised for what they are, or are not sought by the consulting physician. Her type of epilepsy—despite starting in her teenage years—would not be expected to remit; therefore when choosing an antiepileptic drug, the clinician must consider the possibility of future pregnancy. In retrospect, Nicola was lucky not to be taking sodium valproate when she was pregnant, as we now know it to be not just physically but cognitively teratogenic.

It is always a difficult decision to change antiepileptic medication to become pregnant—and one to be made (as far as possible) in close collaboration with the prospective mother, providing her with as much information as possible. We do not often counsel people to come off their drugs, but undoubtedly some people do and never let us know about it.

Epilepsy is not one condition but an umbrella of many disorders each with the same symptom: seizures. A consequence of this is that, even with an electroclinical syndromic diagnosis like juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, people respond differently to medication, making it very difficult to match the right person to the right drug.

It can be enormously stressful when the drug control fails after a period of months or years and

it is not clear what to do next. Uncertainty in the absence of good evidence often results in a variety of clinical approaches and patients can feel like the doctors are “experimenting” on them until either good seizure control is achieved, or either party loses enthusiasm for further drug changes.

Nicola’s story is the description of a journey where she has overcome the shock of diagnosis, faced the trial of social restrictions (like driving),

navigated the apparent inequalities of NHS care, and still remained a mother, wife, and teacher—rather than being labelled as a person

with epilepsy.