د. حسين محمد جمعة

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنةالبورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2012

Management of chronic epilepsy

• BMJ 17 July 2012)Epilepsy can be defined pragmatically as the occurrence of at least two unprovoked epileptic seizures. It is the commonest serious neurological condition in adults, directly affecting over 400 000 people in the United Kingdom and up to 60 million people worldwide.

Prevalence of epilepsy in developed countries is about 0.5%; however, the lifetime risk of a person having a non-febrile epileptic seizure is much higher at 2-5%,implying, for most patients, remittance of the condition or premature death.

Risk of a second seizure occurring within two years of the first event is about 50%. Early treatment with antiepileptic drugs after the first seizure does not affect the long term prognosis, with 75-80% achieving remission at five years, irrespective of

whether treatment began after the first seizure or only after arecurrence.

Treatment is therefore typically reserved for people

who have had at least two seizures; the risk of a third seizure in these patients is over 70%.

A tailored approach to treatment should always be adopted, since there could be circumstances in which treatment after a first seizure is appropriate (for example, presence of a structural lesion on neuroimaging) or deferred (for example, in those with very infrequent seizures).

Most people with epilepsy eventually become free of seizures on antiepileptic drugs. Nevertheless, about 20-30% of patients continue to have seizures despite treatment.

Epilepsy carries an increased risk of morbidity and premature mortality with standardised mortality rates two to threefold higher than the general population.

This raised risk is partly due to the underlying cause of the epilepsy but is also a direct result of seizures, such as an increased risk of accidents (including drowning) and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (a condition that affects at least 500 people with epilepsy in the UK annually). On this basis, seizure remission, wherever possible, is a major goal.

The implications of chronic epilepsy extend beyond continued seizures, and encompass cognitive difficulties, mood disturbance, and lifestyle issues, the effective treatment of which involves a coordinated response from both primary and secondary care.

Who gets epilepsy?

The incidence of epilepsy is increased in childhood, at least partly because of brain malformations, perinatal cerebral insults, and genetic disorders, and in later life, usually as a result of cerebrovascular disease. Nevertheless, seizures could start at any age and may follow a cerebral insult, such as head injury,intracranial infections, or tumours.

The risk of developing epilepsy increases in the presence of learning disability or after a prolonged or lateralised febrile convulsion in childhood.

Genetic factors contribute either directly (for example, in the autosomal dominantly inherited condition tuberous sclerosis) or in a more complex pattern of polygenic inheritance.

Overall, genetic factors are thought to contribute to about 40% of people with epilepsy

What is the goal of epilepsy treatment?

In all people with epilepsy, the goals hould be to achieve seizure freedom. Reducing a person’s seizures by 50%, for example,from six seizures to three seizures a month might have a minimal effect on quality of life.This is largely because of therestrictions to a person’s lifestyle that remain until seizure freedom, such as the inability to drive, difficulties obtaining work, and maintaining a relationship.

Nevertheless, antiepileptic drugs have both idiosyncratic and often more predictable chronic side effects, and seizure freedom should not be relentlessly pursued at the expense of quality of life; intrusive side effects also have a negative effect on quality of life.

Common side effects that lead to withdrawal of drug treatment include drowsiness, dizziness, lethargy, and cognitive slowing. These side effects are a particular concern for combination antiepileptic drug treatment.

How is epilepsy managed?

The diagnosis of epilepsy is clinical—that is, it is made on the basis of a description of the seizure by both a patient and awitness. It is mandatory to try to obtain a witness description, which is often more informative than the person’s account of the event, which may be confounded by loss of awareness, confusion, and amnesia.

Investigations such as a brain scan by

magnetic resonance imaging or an electroencephalography recording should be used to corroborate clinical suspicion and not as screening tests, owing to the presence of both false positive and false negative information.Patients should be referred to a specialist for evaluation if a seizure is suspected,but drug treatment is typically started only after a second seizure.

The choice of initial monotherapy has been guided by several important studies (including, most recently, SANAD ) and advice from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).

The antiepileptic drug strategy should be

tailored to each patient’s seizure type, epilepsy syndrome, cotreatment, comorbidity, lifestyle issues, and preferences (box1).

Summary points

Epilepsy is common, affecting over 400 000 people in the United KingdomEpileptic seizures are associated with an increased risk of morbidity and premature mortality Quality of life depends on seizure freedom and lack of adverse effects from drug treatment Comorbidities and the effects on lifestyle, mood, and relationships are also important Up to 75% of people with epilepsy become seizure-free on treatment Choice of drug treatment should be tailored to each person, as determined by their characteristics, the epilepsy syndrome, seizure types, lifestyle issues, and cotreatments

Combination treatment could be needed for patients who do not respond to monotherapy

Review diagnosis and treatment compliance for patients who do not respond to treatmentConsider other treatment options, such as surgery, in people with chronic focal epilepsy

Specialists should adjust the dose of the selected drug to achieve optimal seizure control, making increments if seizures continue in the absence of side effects and, for some drugs such as phenytoin, being guided by assays of serum drug concentrations.

Zealous adherence to quoted therapeutic ranges of serum antiepileptic concentrations is, however, not appropriate. These data should always be secondary to the clinical picture of whether the person continues to have seizures or dose related side effects from antiepileptic drugs.

Blood levels of antiepileptic drugs should also be monitored to detect non-adherence to the prescription, suspected toxicity, and in the

management of specific clinical conditions such as status epilepticus, organ failure and pregnancy, in which serum levels may fall resulting in the re-emergence of seizures.

Treatment should be initiated and continuing therapy should be planned by the specialist. If management is straightforward, continuing drug treatment can be prescribed in primary care if local circumstances or licensing allow. The duration of each treatment trial before deciding on continuing or changing to an

alternative drug depends on the occurrence of side effects and seizure frequency. For example, it will take longer to establish whether a drug has been effective in a patient with very infrequent seizures than in a patient with daily or weekly seizures.

What affects seizure control and prognosis in chronic epilepsy?

Several factors influence prognosis, and specifically, the chance of patients becoming seizure-free. Perinatal neurological insult and learning disability are associated with an increased risk of developing chronic epilepsy. Only about 10% of people with an epileptic structural lesion on magnetic resonance imaging,such as hippocampal sclerosis, achieve seizure freedom with drug treatment alone. For some of these, epilepsy surgery offers the best chance of becoming seizure-free and improving quality of life.An important factor in the probability of subsequent remission is the frequency of seizures within the first six months after seizure onset; 95% of patients with two seizures in the first six months achieve a five year remission, compared with only 24% of those with more than ten seizures.

The probability of seizure remission decreases significantly with each successive treatment

failure. About 50% of people become seizure-free with their first antiepileptic drug, whereas only 11% who discontinued the first appropriate drug owing to a lack of efficacy become seizure-free on a second drug, and only 4% become seizure-free on a third drug or beyond.

A recent series of studies has suggested, however, that this view is overly pessimistic. For example, in a review of the effect of 265 drug changes in 155 people with chronic epilepsy, 16% were rendered seizure-free after introduction of one drug, whereas a further 21% had aconsiderable reduction in seizure frequency.

Overall, 28% of the cohort was rendered seizure-free by one or more changes to their drug treatment.

Box 1: Information needs

General epilepsy informationExplanation of what the condition is

Classification

Investigations

Syndrome

Epidemiology

Prognosis

Genetics

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy

Seizure triggers

Lack of sleep

Alcohol and recreational drugs

Stress

Photosensitivity

First aid

General guidelines

Issues for women

Contraception

Preconception

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Menopause

Antiepileptic drugs

Choice of drug

Efficacy

Side effects

Adherence

Drug interactions

Free prescriptions

Lifestyle

Driving regulations

Employment

Education

Leisure

Relationships

Safety at home

Possible psychosocial consequences

Perceived stigma

Memory loss

Depression

Anxiety

Maintain mental wellbeing

Self esteem

Sexual difficulties

Support organisations

Address and telephone numbers

What are the factors to consider if seizure

control is suboptimal?

Is the diagnosis correct?

A patient’s failure to respond to adequate trials of antiepileptic drugs should prompt specialists to review the diagnosis. One study showed that up to 20-30% of people attending tertiary referral centres with presumed chronic epilepsy did not in fact have the condition, with the most common differential diagnoses being dissociative seizures and neurocardiogenic or cardiac syncope.

Is the drug treatment appropriate?

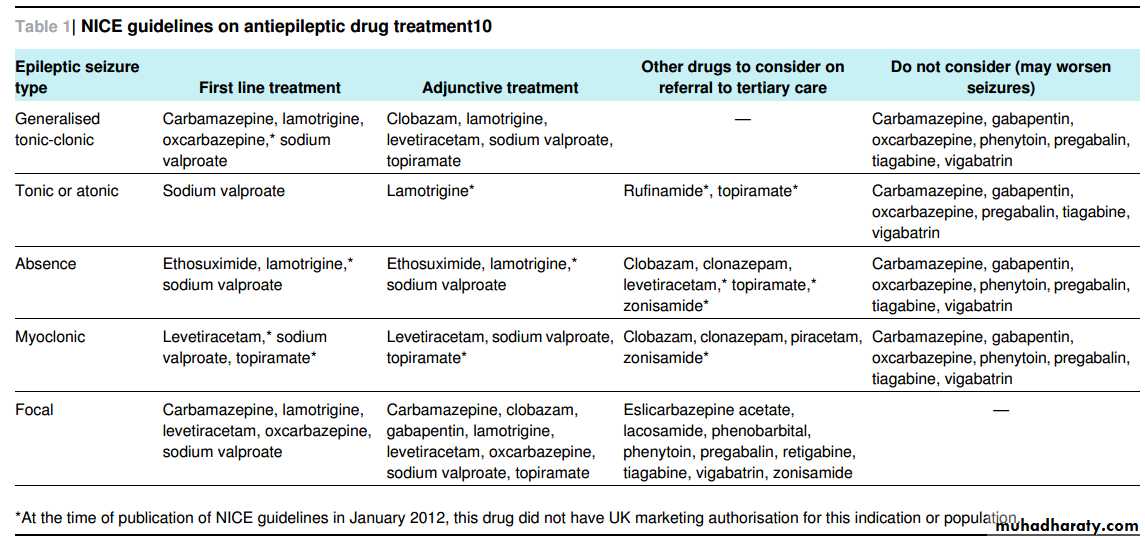

Some antiepileptic drugs could exacerbate seizure disorders if used injudiciously. The most common examples are the use of carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, pregabalin, and gabapentin in primary generalised epilepsy, all of which canexacerbate not only absences and myoclonic jerks but also convulsive seizures. Therefore, a patient’s seizure disorder must be classified accurately, although this is not possible in some instances and drugs with a broad spectrum of activity should be used (table⇓)

What other medications and illnesses need

to be considered?Other non-epilepsy drugs may lower the seizure threshold, including antimalarial compounds (such as chloroquine, mefloquine), smoking cessation drugs (such as bupropion), antidepressants, and antipsychotics (such as amitriptyline and clozapine). Use of these drugs should be questioned if seizure control is suboptimal. Systemic illnesses, such as sepsis, renal

or hepatic disease, or an endocrine disturbance, may cause treatment failure and should be investigated.

Is adherence to treatment adequate?

If there are doubts about adherence to treatment, the patient and carer should be questioned sensitively about this. Serum concentrations of antiepileptic drugs can also be obtained.Inspecting the packaging and drugsthemselves may rarely yield prescribing or dispensing errors. If adherence is a problem, consider using dossett boxes, prepackaged treatment packs, and reminder services (such as alarms or regular, timed text messages).

Has the patient had a good trial with amaximally tolerated dose of all major

antiepileptic drugs?People with poorly controlled epilepsy are usually under the care of a specialist neurology team. If seizures continue despite a maximally tolerated dose of individual first line drugs,

specialists should trial a combination of two first line drugs for that seizure type. The chance of dual therapy controlling seizures, if monotherapy has been unsuccessful, is 10-15%.

If dual therapy does not help, the drug which seems to have the most effect and fewestside effectsshould be continued, and the second drug should be gradually replaced with an adjunctivedrug. NICE guidelines may help in selecting an alternative, second line antiepileptic drug (table).

The chance of a 50% reduction in seizures from the addition of a second line drug is 20-50%, with the chance of the patient becoming seizure-free less than 10%.

If the second line drug is effective, consider withdrawing the initial drug. Prescription of an unhelpful second line drug should not be continued. If adjunctive treatment is ineffective or not tolerated, discuss this with the person, and possibly refer them to a tertiary epilepsy specialist. Current NICE guidelines recommend other antiepileptic drugs to consider at this point for focal epilepsy, such as lacosamide, eslicarbazepine acetate, pregabalin, zonisamide, retigabine, and tiagabine, as well as the

older substances phenobarbitone and phenytoin.

Over the past 20 years, the number of antiepileptic drugs available has increased markedly (see figure⇓ and table).

Similarities exist between drugs in terms of efficacy and indications, but there is a wide range of dosing strategies, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions, and side effect profiles. This complexity has led to a degree of “prescribing paralysis” among non-specialists, and clinicians will often retreat to established and trusted drugs, rather than considering more contemporary and newly licensed drugs.

Which drug should the patient try next?

With a large number of drugs to choose from, how do specialists choose drugs rationally—that is, tailor the choice of treatment to an individual? Many placebo controlled trials of adjunctive antiepileptic drugs have formed the bases on which individualdrugs have been licensed. Establishing which drug is the most effective and well tolerated by comparing these trials is difficult because of different trial designs, patient selection, and outcome measures. Nevertheless, detailed analysis shows no clear statistical difference between the drugs in terms of efficacy and

tolerability, and therefore one drug cannot be stated as conclusively better than anothe

Head to head trials of adjunctive and combination treatments offer greater potential for establishing a drug hierarchy. Few such studies exist, and those that have been undertaken frequently evaluate outcome measures other than seizure frequency, such as mood changes and aggression.

These goals are laudable but do little to inform which drug or combination to recommend next for people with refractory epilepsy to improve seizure control.

In reality, the choice of the third or fourth antiepileptic drug or beyond is complex and involves looking at the evidence, clinical experience, and individual characteristics and concerns. For example, in people with comorbidities such as migraine, choosing a drug with adjunctive preventative properties for migraines may be beneficial (such as topiramate, sodium valproate, pregabalin, or gabapentin).

In people with anxiety or depression, compounds that are also indicated for generalised anxiety disorder (such as pregabalin) or other drugs with mood

stabilising properties (such as valproate and lamotrigine) may be worth considering earlier than other substances. In people with an elevated body massindex, consider avoiding pregabalin, sodium valproate, and gabapentin, and consider instead topiramate and zonisamide, which are commonly associated

with weight loss.

The presence of cotreatments, particularly those affected by enzyme inducing drugs, may influence the choice of drug. Oral anticoagulants may need an increased dose to maintain appropriate anticoagulation levels, and hormonal contraceptives

are rendered less effective, even with a dose adjustment, in the presence of drugssuch as carbamazepine, phenytoin, and higher

dose topiramate. Other drugs with favourable pharmacokinetics,such as levetiracetam, may be better choices. Teratogenicity is a clear concern with all drugs, and particularly in combinations including valproate.

How can the total drug load be minimised?

It is important to reduce and discontinue antiepileptic drugs if their prescription has not aided seizure control and they are suspected of giving rise to adverse effects. Reduction of the number of antiepileptic drugs frequently results in patients feeling better and improved seizure control.The rate at which these drugs should be withdrawn in this situation is controversial and should be planned and supervised by specialist services.

Some drugs can be safely withdrawn fairly rapidly, but conventional withdrawal occurs over a period of weeks. This period is particularly important in the withdrawal of benzodiazepines and barbiturates, which could precipitate status epilepticus if withdrawn too rapidly.Making only one drug change at a time is recommended, to determine cause and effect

if there is any improvement or deterioration.

What about epilepsy surgery?

In focal epilepsy, if satisfactory seizure control cannot be achieved by antiepileptic drugs, consider an evaluation for epilepsy surgery. This treatment is especially indicated if alesion with concordant clinical features has been detected on magnetic resonance imaging, but should be considered in patients with a focal onset epilepsy and ongoing seizures despiteoptimal doses of two to three antiepileptic drugs (as

monotherapy or in combination).

How often should people with epilepsy be

reviewed?Current NICE guidelines recommend that all people with

epilepsy should have a yearly structured review. In adults, this review may be undertaken by a general practitioner or specialist, depending on how well the epilepsy is controlled and the presence of specific lifestyle issues, such as consideration of pregnancy, driving regulations, or drug cessation (box 2).

At this review, people should have access to written and visual information, counselling services, timely and appropriate investigations, and tertiary services (box 1). In particular, if seizures are not controlled or diagnosis is uncertain, patients should be referred to tertiary services for further assessment.

What should an epilepsy review include?

Pharmacological aspectsAt the annual epilepsy review, the person’s treatment should be discussed. This discussion will include an evaluation of the effectiveness of the prescribed drugs and presence of adverse effects. Common side effects to almost all drugs include

drowsiness, dizziness, and lethargy; these effects, in addition to specific side effects for each drug, should be actively sought.

The effect of comorbidities and use of cotreatments should be reviewed, such as the oral contraceptive pill or anticoagulants. Routine monitoring of antiepileptic drugs is not indicated because it is unlikely to alter drug management in isolation.

Non-pharmacological aspects

The implications and consequences of chronic epilepsy should be considered, which often are more devastating than the seizures themselves. Patients should be given general safety advice about cooking with a microwave oven,safe bathing, and recreational activities. The driving regulations should be discussed if appropriate, and patients should be reminded that a one year period of seizure freedom is required before beingeligible to drive. Issues regarding epilepsy, antiepileptic drugs,contraception, and pregnancy should be considered in women of childbearing age and further advice sought from a specialist if relevant.

A discussion of reasonable expectations and

limitations with regard to the prognosis and the prospects for independent living, leisure and social life, and employment is also important. For patients and their families, the support of an epilepsy specialist nurseand of voluntary organisations, such as the Epilepsy Society, are invaluable.

Box 2: Triggers for referral to secondary care

All patients with a suspected epileptic seizureAll patients who continue to have epileptic seizures (that is, active epilepsy)

Patients who have possible side effects, both acute and chronic, from drug treatment Patients with stable epilepsy but a change of circumstances, such as pregnancy Consideration of treatment withdrawal

Patients needing additional specialist information, such as preconception counselling.