The management of overactive bladder syndrome

BMJ 17 April 2012د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2012

In 2010, the International Continence Society restated the

definition of overactive bladder syndrome as a condition withcharacteristic symptoms of “urinary urgency, usually

accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without urgency

incontinence, in the absence of urinary tract infection or other

obvious pathology.”1 In 2009, disease specific total expenditures

for this syndrome exceeded $24.9bn (£15.76bn; €19.01bn).2

However, overactive bladder syndrome remains underdiagnosed

and undertreated, despite prevalence estimates in men and

women of 17% in the United States (National Overactive

Bladder Evaluation study) and 12-17% in six European

nations.

One population based prevalence study found that

60% of older or disabled patients seek treatment but only 27% receive it. The study also showed that overactive bladder syndrome is associated with worse quality of life scores than those in hypertension, depression, diabetes, and asthma. In fact,

many patients are unaware that useful medical treatment is available.

Retrospective observational studies have shown that

the medical and surgical consequences of overactivebladder—particularly in older or disabled patients—include

depression, falls, fractures, urinary tract infections, and skin

infections.5 The condition is particularly challenging to screen

for, diagnose, and treat because the causes are unknown. We

review the diagnosis and management of overactive bladder

syndrome drawing on examples from US Preventive Services

Task Force levels I-III clinical evidence .

Who gets it?

Although overactive bladder syndrome is most common in

patients over 40 years of age,4 it can also affect children andyoung adults. It is important to correct the common assumption that the syndrome is an inevitable part of ageing.

What causes it?

Overactive bladder syndrome is sometimes referred to as “detrusor overactivity.” The causes are probably multifactorial.There may be injury to a central inhibitory neural pathway, with or without deregulation of an afferent sensory bladder pathway,which suggests a neurogenic component. A myogenic component is also a possibility because there seems to be potential for partial denervation of the bladder muscle with

increased excitability and an involuntary rise in pressure within the bladder.

Clinicians should ask about caffeine intake and foods that can irritate the bladder, including spicy foods and citrus fruits, both

Basic science research and expert opinion have prompted the recent hypothesis that detrusor overactivity results from deregulation of detrusor muscle phasic activity.

How are patients with overactive bladder syndrome assessed?

There are usually no clinical signs on examination, so a careful history is essential (box 2). Patients may have urgency, frequency (more than eight voids per 24 hours), or nocturia (two or more voids after falling asleep and a return to sleep after voiding), with or without urge incontinence. There must be an absence of obvious urinary tract disease including urinary tractinfections, calculi, and bladder tumours.

of which acidify the urine. Other bladder irritants include carbonated drinks, tomato based food products, artificial sweeteners, and processed foods (which contain artificial ingredients, preservatives, and flavourings).

Caffeinated and alcoholic drinks are diuretics and can greatly increase urine production.

Symptoms should be considered in the context of the patient’s 72 hour voiding diary. The range of frequency in normal healthy patients is four to eight voids per 24 hours, so an increase above

this may be important. Nocturia is defined by waking to void, voiding, and returning to full sleep. Without a return to full sleep, subsequent voids are not included in the nocturia count and may suggest a sleep disorder instead.

Urge incontinence—involuntary leakage of urine accompanied by or immediately preceded by urgency—is another useful symptom

that is easily documented on voiding diaries.

Objective assessment tools are useful to quantify symptom severity and assess the effects of treatment. Voiding diaries provide information about the amount and time of voiding, severity of urgency, episodes of stress or urgency incontinence, pad usage, and oral intake; patients record data for at least 48-72.

The international consultation on incontinence, urinary distress inventory, and incontinence impact

questionnaire are patient reported quality of life measurements that have been derived and validated for research and for use by clinicians. Pfizer has developed two disease-specific questionnaires that are now commonly used by general practitioners, urologists, and gynaecologists: the overactive bladder questionnaire and its short form version .

The longer questionnaire has 33 items, which assess social interaction, sleep, concern, and coping skills, whereas the short form has 19 items, which assess “bother” and quality of life measures that may be useful in the consultation to screen for the syndrome.

Clinical guidelines for when GPs should refer to a specialist are

available at the National Institute for Health and Clinical

Excellence.11 Criteria for urgent specialist referral include

macroscopic haematuria, microscopic haematuria in patients

over 50 years of age, recurrent urinary tract infections associated with haematuria in patients over 40 years, and a suspected

malignant genitourinary mass. Less urgent referral criteria

include consistent urethral or bladder pain, clinically benign

pelvic masses, faecal incontinence, potential neurological

pathology, persistent symptoms of voiding difficulty,

genitourinary fistula, history of continence surgery, and a history

of pelvic cancer surgery or pelvic radiotherapy.

Referral

Investigations

Over the course of the first few clinic visits, patients shouldcomplete a 72 hour voiding diary (one per visit), have a uroflow

assessment (the maximum speed of urination with at least 150 mL voided plus residual urine), and undergo multiple ultrasound

post-void residual volume determinations.

These assessments will help to discern whether the patient has problems with the storage or emptying of the bladder contents and may need referral to a urologist, gynaecologist, or urogynaecologist.

Patients who are resistant to conservative treatment may need more sophisticated assessments of bladder function, including urodynamics, videourodynamics, and neurophysiological outpatient studies.

Urodynamics may help to assess the underlying cause and to determine the appropriate treatment. For example, some patients whose symptoms are complicated by urinary incontinence

cannot differentiate between symptoms of stress and urge incontinence; stress incontinence in these patients with mixed symptoms will often hinder improvements in urgency until the stress incontinence component is identified by urodynamics and dealt with, potentially with minimally invasive surgery including a midurethral sling.

The European Association of Urology and the Japanese Urological Society have suggested a two part approach to

How is overactive bladder syndrome treated?

management—initial or first line treatment followed by

specialised secondary treatment. The core treatmentincorporates dietary modifications, bladder retraining, pelvic floor retraining with and without biofeedback, and anticholinergic drugs as first line medical treatment. It is best practice to discuss behavioural modification therapy with all patients, although not everyone can adhere to the required actions.

The goal of treatment is to attain an adequate

improvement in symptoms, as shown by a reduction in total score on a verified standardised overactive bladder syndrome questionnaire in any of the symptoms of urgency, frequency,nocturia, and urge incontinence while minimising the potential side effects of drugs.

Lifestyle modification

Potentially useful dietary measures may include a reduction in the intake of fluids, caffeine, acidic foods, and alcohol, in addition to weight reduction and smoking cessation. In arandomised crossover trial, patients were asked to increase or decrease their fluid intake, following a predetermined fluid regimen. People who reduced their daily intake by 25% had asignificant improvement in frequency, urgency, and nocturia.Many participants had difficulty in reducing their oral intake by 50%.

The effects of caffeine have been evaluated in observational studies and other randomised double blind placebo controlled prospective trials. An observational study assessed the effects

of caffeine at a dose of 4.5 mg/kg on bladder function by performing uroflowmetry and cystometry before and after each participant drank water with and without caffeine on two separate occasions.

Caffeine caused diuresis and a quicker urge

to void while increasing the speed of urination and the amount voided. The study concluded that caffeine can promote urgency and frequency, and it is recommended that patients with overactive bladder symptoms carefully manage their caffeine consumption. One prospective cohort study included 123 morbidly obese women who had bariatric surgery. The study monitored improvement in overactive bladder symptoms after surgery and weight loss (patients had a mean body mass index of 47.5 before surgery and 31.0 after surgery) over a mean follow-up of 1.7 years.

Patients had a significant reduction in frequency and stress incontinence, and improvement on the urinary distress inventory and incontinence impact questionnaire

score. A questionnaire study assessed the effect of smoking

status and intensity on overactive bladder symptoms; 3000

questionnaires were mailed to randomly identified patients from the Finnish population register. Smoking was significantly associated with urinary urgency (odds ratio 2.7, 95% confidence interval 1.7 to 4.2 for current smokers and 1.8, 1.2 to 2.9 for former smokers compared with non-smokers) and frequency (3.0, 1.8 to 5.0 and 1.7, 1.0 to 3.1).

Smoking was not associated with nocturia or stress incontinence.

Compared with light smoking, heavy smoking was associated with a risk of urgency (2.1, 1.1 to 3.9) and frequency (2.2, 1.2 to 4.3). Several single arm prospective studies have shown that reducing night-time fluid intake reduces nocturia and improves quality of life symptom scores. However, the resultant concentrated urine can also act as a bladder irritant because of its increased acidity.Behavioural bladder retraining

A 2000 modified crossover study found that bladder retraining is most effective when combined with oral drugs. Behavioural therapy can be both labour intensive and time intensive because it has multiple components and patients need to be educated as to how to use them all. It is important to communicate to the patient that treatment requires motivation and patience, withoutwhich long term improvements will not be achieved.

The main components of bladder retraining are timed and delayed voiding,

as well as dietary modifications and pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation, with or without biofeedback.Initially, voiding intervals may be as short as every 30 minutes, with the time between voids being slowly

increased over several weeks until the patient can maintain

control for periods of three to four hours. This regimen slowly increases the bladder capacity and may reduce the number of episodes of urgency and urgency incontinence. Patients need to keep a written urination log so that they can verify improvement or worsening of symptoms.

Expert opinion suggests that this approach is less successful in non-ambulatory patients (who often have comorbidities such as pelvic or leg fractures, obesity, or heart failure) because it is labour intensive

for patients, care givers, and other medical staff. The addition of pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation, with or without biofeedback, may improve symptom control for ambulatory patients through improving isolation of the levator ani muscles.

However, to gain appropriate muscle control and strength, as well as prolonged symptom improvement, exercises must be completed regularly, preferably daily, but weekly at least.

A bladder diary that records daily frequency, urgency, nocturia, and urge incontinence episodes and their severity will help the patient and doctor to evaluate conservative treatment and to isolate exacerbating factors, such as foods eaten, activities performed, timing of diuretic drugs, and worsening comorbidities.

Drug treatments

Drugs—usually anticholinergics—that suppress symptoms of overactive bladder are the mainstay of current medical management. Anticholinergics (also known as antimuscarinics) improve symptoms via two mechanisms: by competitively inhibiting the binding of acetylcholine to the bladder musclewall (detrusor muscle) and by potentially inhibiting urothelial sensory receptors and directly decreasing afferent nerve activity.

A 2008 meta-analysis of anticholinergic drugs in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome concluded that these drugs are well studied, safe, tolerable, efficacious, significantly improve certain measures of quality of life, and should remain as first

line treatment. A 2006 Cochrane review assessed 61 trials that compared anticholinergic drugs with placebo (42 with parallel group design and 19 crossover trials), with a total of 11 956 patients.

At the end of treatment, there was a significantly

greater chance of cure or improvement (relative risk 1.39, 1.28to 1.51; leakage episodes per 24 hours: weighted mean

difference −0.54, −0.67 to −0.41; number of voids per 24 hours:

−0.69, −0.84 to −0.54). The placebo effect is also important in

the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome. A 2009

meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled studies of

antimuscarinic drugs concluded that placebo response is both

substantial and heterogeneous with commonly used clinical

endpoints, including a reduction in episodes of frequency,

urgency, and urge incontinence.

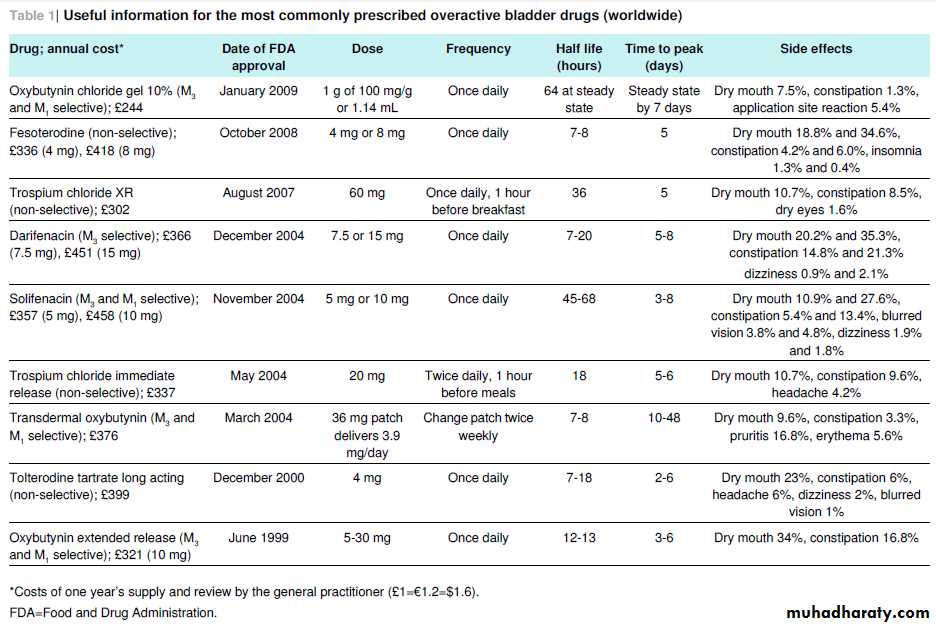

At the end of 2011, at least 11 commonly prescribed anticholinergic drugs were commercially available in the US and Europe, many of which have less expensive generic equivalents as well as time release

formulations (table⇓).

Many patients fail to adhere to their oral drugs in the first three months of treatment, perhaps because improvement may come slowly and by small degrees or because of side effects.

retrospective cohort study in 2008 showed that patient adherence to anticholinergic drugs is still suboptimal.

Dry mouth and constipation are the two most common adverse effects of anticholinergic drugs. A prospective observational study found that this may lead to the discontinuation of treatment in 50% of patients. Constipation may potentiate symptoms,

because excessive stool in the rectal ampulla decreases bladder capacity, so recommend fibre and stool softeners early on during treatment if constipation is a problem.

Antimuscarinics can have serious side effects, such as confusion and cognitive deficits, particularly in older people. Older patients may experience greater central nervous system toxicity secondary to cerebrovascular disease and other conditions that

can affect the permeability of the blood-brain barrier. The use of agents with reduced blood-brain barrier penetrance (such as trospium and darifenacin) may prevent cognitive side effects in these patients.

Other central nervous system effects include

dizziness, somnolence, insomnia, and sedation.w4 Factors that may increase the adverse events of antimuscarinics in older people include reduced rate of drug metabolism in the liver and kidneys, changes in the numbers of muscarinic receptors in thebrain, and the likelihood of polypharmacy.

Vagolytic action in the cardiovascular system may lead to

alternations in heart rate and blood pressure. An M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor selective agent may be preferable in patients with pre-existing heart disease. Several antimuscarinic drugs are relatively M3 receptor specific, but it is unclear whether they are better than non-selective ones.Alternative routes of delivery are available for people who have difficulty swallowing or experience side effects from oral drugs. For example,

oxybutynin chloride may be used as a patch or gel—a 1 mL/100mg dose of a 10% gel applied to the upper arm, abdomen, thigh, or shoulder delivers a constant dose of oxybutynin over 24 hours, and this method of delivery may be associated with reduced adverse effects.

Antimuscarinic agents are variably excreted unchanged in the urine. Their therapeutic effect may be partly mediated by direct nteraction with the urothelium, so drugs that are excreted

largely unchanged in the urine, such as trospium, might have some advantages over other agents, although this has not been seen in clinical studies. However, this potential mechanism of action means that these drugs might be able to be directly instilled into the bladder as intravesical therapy.

Because successful treatment of symptoms is related to

adherence to drugs, encourage patients to persevere (withinreason) and take their drugs as prescribed.w8 Regular follow-ups are important to monitor treatment effects and adherence. We have found that adherence can be improved by educational initiatives such as recommending reasonable, achievable treatment goals of up to a 50% reduction in urgency, frequency, nocturia, and urge incontinence (as documented by voiding diaries or quality of life measurements); encouraging a bowel regimen to combat constipation; and incorporating the use of

reduced glucose or no glucose sweets (for patients with diabetes) or other sialogogues to alleviate dry mouth.

It is also important to discuss contraindications to the use of anticholinergic drugs with patients because they often do not mention all of their medical problems to the specialist.

Contraindications include hypersensitivity to these drugs, untreated angle closure glaucoma, partial or complete gastrointestinal obstruction, hiatal hernia, gastro-oesophageal reflux, intestinal atony, paralytic ileus, toxic megacolon, severe colitis, myasthenia gravis, and urinary obstruction. Patients with

these conditions may be best managed with other conservativemeasures such as timed voiding or pelvic floor retraining; alternatively, they will need clearance for the use of these drugs from the clinician caring for the disorder.

Assessing the success of first line treatment

Complete cures are rare, and—given the variability in lifestyle and fluid intake on a day to day basis—may be short lived.Improvement is measured by a reduction in the number of 24 hour voids and in the number of episodes of frequency, urgency, and urge incontinence.

Measurable improvement may take as

long as 12 weeks, although it is sometimes seen as early as aweek after starting treatment. It is reasonable to allow a four week window for assessing treatment response. After this time,if symptoms have not improved adequately and side effects have not been problematic, the drug can be titrated to a higher dose.

We find that patients can see little improvement with one drug but a clinically relevant improvement when switched to anew drug within the same class. Treatment failure with one or even several drugs in the same class does not imply that the entire class will be ineffective for a particular patient, and persistence is needed.

Treatment of recalcitrant overactive bladder

syndrome

A few minimally invasive second line treatments can be tried if anticholinergic drugs are unsuccessful.

Direct multiple injection of the detrusor muscle with botulinum toxin via cystoscopy is one such treatment. It is thought that botulinum toxin A selectively blocks the presynaptic release of acetylcholine from nerve endings to result in postsynaptic flaccid aralysis of muscle.

Other afferent effects via sensory and pain fibres have also been proposed. This treatment can be administered in the clinic with local intravesical anaesthesia with viscous lidocaine or similar.

A recent randomised placebocontrolled trial found that, compared with placebo, botulinum toxin A reduced urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence by 35-50% and significantly improved urodynamic parameters, including increased maximum cystometric capacity (ability to hold urine) and increased volume before first involuntary detrusor contraction. However, the effects of this treatment begin to diminish at six to nine months and repeat treatments are necessary.

A prospective cohort study reported that the improvement after multiple injections was maintained,

although the dropout rate after two injections was 37%.w13 The

most common reasons for discontinuation were insufficient

efficacy (13%) and temporary urinary retention (11%).w13

Sacral neuromodulation and percutaneous tibial nerve

stimulation are the only two second line treatments currently

approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the US for

the management of recalcitrant overactive bladder syndrome.

Sacral neuromodulation was approved in 1997 for the treatment

of this syndrome; a mild electrical current is sent unilaterally

from a pulse generator (about the size of a cardiac pacemaker)

implanted in the buttock to the sacral nerve (S3) via an implanted

neurostimulator electrode lead placed through the S3 foramen

adjacent to the S3 nerve root.

Patients feel the stimulation in the bladder, rectum, perineum, or vagina (or a combination thereof).

The exact mechanism by which this treatment works is still being investigated, but one theory is that it restores an equal balance between the inhibitory and excitatory neural voiding control systems. A single centre retrospective cohort study that analysed data on patients with follow-up of one, three, five, and

10 years reported an overall 80% reduction in symptoms. Potential side effects include late failure (return of symptoms

after one year), lead migration, and infection of the implanted

pulse generator. The cost of sacral neuromodulation surgery inthe United States approaches $90 000 for stage one and two

procedures combined.

Posterior tibial nerve neuromodulation was first described in

1983, and a recent review of a retrospective observational study

has confirmed a 60-80% success rate for patients with

recalcitrant disease.w15 A small needle is inserted into the lower

leg near the ankle, and an external stimulator sends a constant

electrical signal through the tibial nerve retrograde to the sacral

plexus, which regulates bladder and pelvic floor function.

Treatment comprises a 30 minute session once a week for 12weeks. Although the treatment is low risk and not associated with any serious adverse effects, ongoing maintenance treatment may be needed. Posterior tibial neuromodulation is approved

by the FDA for use in overactive bladder syndrome and in Europe is used extensively to treat faecal incontinence.

Level III clinical evidence shows that surgery to augment the size of the bladder by adding to its intraluminal surface area with the interposition of a 10-15 cm loop of small bowel or stomach—referred to as an augmentation enterocystoplasty—is

also of benefit to patients with recalcitrant disease. These large scale operations require many hours of surgery, days of hospital stay, and weeks of convalescence.

A few retrospective cohort studies have shown that these operations reduce urgency, but at the potential cost of incomplete emptying of the new bladder,

which may necessitate clean intermittent catheterisation on atemporary to permanent basis. It cannot be predicted preoperatively which patients will succumb to this potential complication. An observational retrospective study assessed augmentation enterocystoplasties in women with recalcitrant

urgency symptoms with a mean follow-up of 29 months.

Eight of 10 patients were cured of urgency symptoms and eight of 10 were also able to void spontaneously, while one used self catheterisation once daily and the other an indwelling Foley catheter. Expert opinion suggests that several options exist for patients with recalcitrant urgency, so the use of augmentation

has probably decreased, although it can still be used as asuccessful third line intervention.

An eight year prospective cohort study assessed bowel problems after augmentation cystoplasty in 116 patients, 30 of whom had recalcitrant overactive bladder symptoms. It found that 59% of patients

had troublesome diarrhoea, 50% of whom were managed with daily antidiarrhoeal drugs; 47% had faecal incontinence, 41% with faecal urgency and nocturnal bowel movements (18%).

These complications affected work (36%), social function (50%), and sexual activity (43%).

Might new oral drugs be available in the future?

Drugs under study target specific receptors or other bladder muscle or nerve physiological processes at the Rho-kinase pathway, in addition to neurokinin 1 antagonists and calcitonin gene related protein receptor antagonists, which act at the levelof the spine. Two new anticholinergic drugs studied in phase II trials include PSD-506, an M2 and M3 selective agent, and SMP-986, a β3 adrenoceptor agonist that reduces bladder muscle contraction.

Other β3 adrenoceptor agonists in trial include

KUC-7483, YM-178, and GW-427353. Cizolirtine citrate, a calcitonin gene related product,w19 and substance P, which together antagonise the neurokinin 1 and calcitonin gene related protein spinal receptors, is also in phase II clinical trials. Similar drugs in phase II trials include TA-5538 and SSR-240600. Rho A pathway inhibitors currently under investigation in phase III trials include a vitamin D3 analogue, Elocalcitol.w20 This may reduce bladder muscle wall stiffness commonly seen in overactive bladder and pelvic organ prolapse, theoreticallyincreasing bladder capacity and potentially reducing frequency and urgency.

Conclusion

Anticholinergics remain the most effective drugs to treat thecomplex symptoms of overactive bladder. Their efficacy,

potency, and side effects have been well studied and recently

confirmed by a large scale meta-analysis. Surgery is the second

line approach for medically recalcitrant patients. Well researched minimally invasive approaches including botulinum A toxin have proved to be effective, with a low complication rate,

although they are more costly than conservative drug treatments.

Newer drugs that target different physiological pathways may

soon replace these treatments, but it is too early to comment on

their future usefulness.

Tips for the general practitioner

Useful information

Ask the patient about urgency and frequency and whether the problem needs treatment If treatment is requested start with a two to three day voiding diary.

Normal voiding is five to eight times in 24 hours

Nocturia with one nightly episode is normal from age 40-80 and twice thereafter .Consider fluid reduction or pelvic floor exercises (or both) for three months in patients with two or more urgency episodes during the voiding diary (as long as they are not taking diuretics and they do not have poorly controlled diabetes with glycosuria).

If these two treatment options do not work start treatment with the lowest dose of any of the anticholinergic drugs listed in the table.

Remember to increase the dose as necessary

When to refer to a urologist, gynaecologist, or urogynaecologist.

When conservative measures, including reduced fluid consumption and pelvic floor exercises, have not been successful.

Patients who have tried the full dose of two or more drugs without clinically significant improvement or those in whom treatment has been discontinued because of side effects

Summary points

Patients with overactive bladder syndrome have a frequent and strong desire to urinate (with or without incontinence), which adversely affects quality of lifeThe causes of overactive bladder syndrome are probably multifactorial.

Verified patient reported outcome questionnaires help assess the severity of symptoms of urgency, frequency, and nocturia and track their improvement with treatment.

Conservative treatments such as reducing fluid intake, avoiding foods and drinks that irritate the bladder, regulating voiding, and performing pelvic floor muscle exercises regularly may be combined with anticholinergic drugs.

Poor adherence to drug treatment is common but may be improved by managing side effects and finding the most suitable drug for individual patients.

Second line treatments include sacral neuromodulation, tibial nerve stimulation, and intermittent botulinum toxin injection into the detrusor muscle.

Box 2 Investigating a patient for overactive bladder syndrome

Note onset of frequency, urgency, nocturia, and urge incontinence. Record the quality and quantity of these symptoms. Determine what improves or worsens these symptoms, whether the symptoms have led to any injuries through falls, and whether the patient is restricting himself or herself to the home.Find out what drugs the patient is currently taking. Diuretics can exacerbate symptoms and α agonists (phenylephrine) can close the bladder neck and lead to overflow incontinence; α blockers can lead to stress incontinence by their relaxing and opening effects on thebladder neck area.

Current and past medical or surgical problems, especially those related to fluid management for heart failure, can increase fluid mobilisation

and overwhelm the bladder, potentially leading to overactive bladder symptoms or overflow incontinence.

Poorly controlled diabetes with blood sugars >1400 mg/L (kidney threshold) leads to severe osmotic diuresis that cannot be controlled with anticholinergic drugs.

Drugs for overactive bladder syndrome will have no effect unless diabetes is more tightly controlled. Once this is accomplished the patient’s voiding diary entries should show an improvement. Strokes and neurological diseases can lead to overactive bladder and

incontinence.

Radiotherapy for uterine, colon, rectal, or prostate cancer can also irritate the bladder wall lining and muscle wall, leading to decreased bladder compliance and capacity.

Surgery such as transurethral resection of the prostate, Burch colposuspension, midurethral slings, and laser prostate therapy can lead to overactive bladder symptoms and can also complicate treatment.

Check for previous treatment for overactive bladder syndrome: obtain old records to verify the procedures and results.

Ask the patient to keep a bladder diary by recording for 2-3 days oral consumption of fluids only (in mL), amount voided, and the severity of the symptoms

Perform urine analysis and culture.

Perform urine cytology if the patient has microscopic haematuria or symptoms of irritative voiding.

Check for glucose using a urine dipstick and, if positive, measure the patient’s glycated haemoglobin to determine the average blood sugar level during the preceding three months. If the value is above normal, a glucose tolerance test is recommended

Measure post-void residual urine (should be less than 50 mL) with ultrasound or straight catheter.

The patient should void immediately before this test if the last void was more than half an hour ago.

If available, perform uroflowmetry before and in sequence with the post-void residual urine. Look for a maximum urinary flow greater than 15 mL/s, with at least 150 mL voided. Values of <150 mL may not accurately reflect the patient’s true maximum flow.

Urodynamic testing may be performed by a urologist, obstetrician, or gynaecologist after referral.

Should we treat lower urinary tract symptoms withouta definitive diagnosis? Yes

BMJ1 December 2011Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are common in the

general population, their main causes (including overactivebladder and benign prostatic obstruction) are not life threatening, definitive diagnosis is invasive, and initial management is safe.

Initial treatment of the symptoms without a definitive diagnosis is therefore sensible and avoids unnecessary secondary care.

Defining the problem

Around 1.8 billion men and women worldwide have LUTS, and the numbers are increasing rapidly as the population ages. The term was introduced in 1994 to escape the “prostate-centric”approach of doctors to lower urinary tract symptoms in men, which led to many men having unnecessary prostate surgery when their symptoms had other causes.

Later, the International Continence Society divided symptoms into three categories:

storage LUTS, including the symptoms of overactive bladder (urgency, urgency urinary incontinence, frequency, and nocturia) and stress urinary incontinence; voiding LUTS, including slow stream and hesitancy; and post-micturition LUTS, such as afeeling of incomplete emptying and post-micturition dribble.LUTS affect patients in many ways. Although symptoms can be bothersome and interfere with quality of life,4 5 not all patients are troubled enough to seek treatment. However, there is undoubtedly considerable unmet need, and some data show that many patients have failed to get treatment, even when they would be happy to accept it.

Urodynamic studies are needed to determine the underlying causes of LUTS. Such studies require the passage of a urethral catheter and are therefore uncomfortable for patients as well as expensive.

Given the large numbers of people with LUTS who

seek medical care, treatment without a definitive diagnosis is the only practical way of managing most patients. Furthermore, my experience is that patients are unlikely to agree to an invasive, uncomfortable investigation if the management they are offered is simple, safe, and relatively inexpensive.Successive international consultations have recommended that urodynamic studies are used only if invasive treatments are being considered. Most patients with symptoms that interfere with their quality of life can be managed by a combination of lifestyle interventions, behaviour modification, and drugs.

Conservative treatment

A definitive diagnosis is not needed to start many of the simple interventions that benefit patients with LUTS. Lifestyle modifications include measures such as manipulation of fluid and food intake. Many patients drink far more fluids than they need, partly because of publicity of the false perception that we need to drink 2 litres of water a day. It has been shown thatrestricting fluid intake improves symptoms of overactive

bladder. There is also evidence that stopping caffeine helps many people with overactive bladder, possibly because caffeine is a mild diuretic and also a direct smooth muscle stimulant.

Overactive bladder with or without urgency incontinence is improved by pelvic floor exercises because contraction of the pelvic floor increases urethral closure pressure, thereby maintaining the pressure gradient essential for continence.

Furthermore, contracting the pelvic floor inhibits the detrusor contractions that are responsible for the symptoms of overactive bladder.

Overactive bladder is also improved by bladder

training—that is, by asking the patient to void every one hour initially and, if that controls their urgency and incontinence, then increasing their inter-void intervals by 15 minutes, at intervals of two to three days, until the patient can void safely,without bothersome symptoms, at socially acceptable intervals.

Prostatic obstruction, and its associated symptoms, can be partly relieved by α adrenergic blocking drugs and 5α reductase inhibitors.

Overactive bladder may be improved by

antimuscarinic drugs and nocturia by judicious use ofdesmopressin.

LUTS are not dangerous, for the most part, although certain symptoms should alert clinicians to the need for further investigation. These include haematuria, dysuria, and new onset nocturnal incontinence, and signs such as an enlarged bladder.

However, even conditions like prostatic obstruction, which were previously thought to be potentially dangerous and to need early treatment, have been shown in longitudinal studies to be relatively benign and show little progression.

Best management

The treatments for LUTS mentioned above are low risk and, for the most part, low cost. Hence, neither the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence’s guidelines on incontinence nor its guidance on male LUTS13 recommend seeking a definitive diagnosis before treatment of symptoms in men or women.In future the aim should be to teach men and women self care as initial management. This would require the production of psychometrically validated self care packages, which are safe to use and clearly indicate when medical care should be sought.

All doctors can continue to treat LUTS without a diagnosis. If symptoms remain bothersome, referral for a urodynamic diagnosis is mandatory if the patient wishes to consider invasive treatments.

Interpreting Urine Albumin: Who Lives? Who Dies?

Medscape Family Medicine © 2012 WebMD, LLC08/14/2012

Robert W. Morrow, MD: Hi, welcome. This is Dr. Bob Morrow. We are doing another recording of a new type of video roundtable, "Primary Care Goes to Urinetown." I am a family physician in the Bronx and Clinical Associate Professor in the Department of Family and Social Medicine at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. We are here with Dr. Lynda Szczech.

I have a question that has been bothering me and hopefully has been bothering you. I hope we get some good answers. Lynda?

Lynda A. Szczech, MD, MSCE: Hi. My name is Lynda Szczech. I am a nephrologist practicing in Durham, North Carolina, and I am proud to be President of the National Kidney Foundation.

During our previous chat, I gave a plug for the National Kidney Foundation's Website, www.kidney.org. I did that because our clinical practice guidelines are posted there. As I said before, they are a bit dry, but chock-full of information. If you need more information after listening to this discussion, please feel free to go to those clinical practice guidelines. I hope they will be of help.

Dr. Morrow: Thank you. Today, we are going to spend a few minutes discussing urinary microalbumin, a very wet subject, and hopefully interesting enough for everybody.

We don't dip our fingers into tests anymore, but the issue came up many years ago, when someone asked me at a quality improvement committee meeting, "Why can't the doctors just test urine microalbumin?" I said that maybe we should tell them that they should do it, and maybe we should tell them why.

The big question here is how often we should do this. Is this something that should substitute for a more quantitative test for total albumin? Is this something that they are going to stop doing at some point? Is it sensible? Is it predictive? Lynda, those are your questions.

Dr. Szczech: All right. Why do it, and who do we do it on? The biggest problem with urine albumin is interpretability, because it seems very complicated initially -- mostly because when you get a urine albumin value and a urine creatinine value, and you divide the 2 to get the ratio, they are in different units. That is kind of weird -- milligrams of albumin per gram of creatinine. You have to watch out for that, and if you get confused, reach out to people. Everybody gets confused by that.

In terms of interpretability, what is the threshold? About 5 years ago, we thought that less than 30 mg/day was great -- if you have 29 mg of albumin per 24 hours, you are going to live forever, but if you are at 31 mg/day, oh my gosh, make sure that your will is in order.

Actually, that threshold of 30 mg/day is not set in stone like we thought. It turns out that between 0-5 (the lower limits of detection) and 30, there is a linear relationship with mortality.

That brings us to 2 points. First, regardless of where you are, if you can detect a number that is greater than 10, you want to get that number lower. In fact, if I had a urine albumin level of 15, 20, or 25 mg/day, I would want to get it lower.

All of the physicians listening to us, as well as other providers, should want to know what their urine albumin is, because it correlates with mortality. It kind of correlates with loss of kidney function, but when you find it, the kidney disease is caught so early that the number of people who will live long enough to develop progressive kidney disease is relatively small.

That's the pearl: Urine albumin correlates with mortality.

It is your way to look at vascular health. Just like when you see proliferative retinopathy in the eyes of a patient with diabetes and know that the rest of the blood vessels probably don't look so good, if you see urine albumin, you should think to yourself that the rest of the blood vessels probably don't look so great and focus on cardiovascular risk factor reduction.

No one ever got hurt by peeing in a cup. It's cheap, easy, and it gives you an even better sense of who is going to live to see another birthday than does high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density-lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol.

Dr. Morrow: You are looking at this as a global measure, and you would then address vascular risk rather than strictly give an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker. This is more a question of total cardiovascular health.

Dr. Szczech: Right.

Dr. Morrow: What is the difference between urine microalbumin and albumin?

Dr. Szczech: Nothing. Microalbumin and albumin are the same thing.

Dr. Morrow: Excellent. I think that has been very helpful. Thank you. We will be coming back with an even more challenging subject. Thanks for coming to listen. Goodbye.