Hormone replacement therapy

BMJ16 February 2012د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2012

This is one of a series of occasional articles on therapeutics for common or serious conditions, covering new drugs and old drugs with important

new indications or concerns. The series advisers are Robin Ferner, honorary professor of clinical pharmacology, University of Birmingham

and Birmingham City Hospital, and Philip Routledge, professor of clinical pharmacology, Cardiff University. To suggest a topic for this series,

please email us at practice@bmj.com.

A 51 year old woman presents to her general practitioner with troublesome hot flushes and night sweats for the past eight months. She is sexually active and her last period was about months ago. She has taken a number of over-the-counter preparations, but none have been effective. She is anxious about

having hot flushes at work and exhausted from sleep disturbance.

She wants advice about managing her symptoms.

What is hormone replacement therapy?

Menopause is a normal physiological event in women, occurring at a median age of 51 years. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) contains oestrogen for relieving menopausal symptoms;

for women who still have their uterus it is combined with aprogestogen for endometrial protection. The oestrogen (oestradiol, oestradiol 17β, oestrone, or conjugated equine oestrogen) can be oral, intravaginal, or transdermal.

The progestogen can be oral, transdermal, or delivered via an intrauterine device (Mirena, Bayer Schering). In HRT regimens the oestrogen is taken daily, with progestogen added either

sequentially (cyclic regimen) or daily (continuous combined regimen) if it is needed. Tibolone is an oral synthetic steroid preparation with oestrogenic, androgenic, and progestogenic actions that can also be used as HRT.

Testosterone can be added to HRT, but the role of supplemental testosterone will not be covered in this case.

The key indication for HRT or tibolone is the presence of troublesome vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes and night sweats, with or without awakening).

Vasomotor symptoms are normal and affect about 80% of women during the menopause transition

and are severe in about 20% of these women. The duration of these symptoms varies, with a median of four years, but may continue for as many as 12 years in about 10% of women. HRT

may be indicated when menopausal symptoms are adversely affecting quality of life.

How well does HRT work?

HRT is currently the most effective treatment for troublesome vasomotor symptoms. A systematic review showed a significant mean reduction in the frequency of hot flushes by around 18 aweek and in the severity of hot flushes by 87% compared withplacebo. Large randomised controlled trials have confirmed that HRT also significantly reduces fracture risk, improves vaginal dryness and sexual function, and may also improve sleep, muscle aches and pains, and quality of life in symptomatic women.

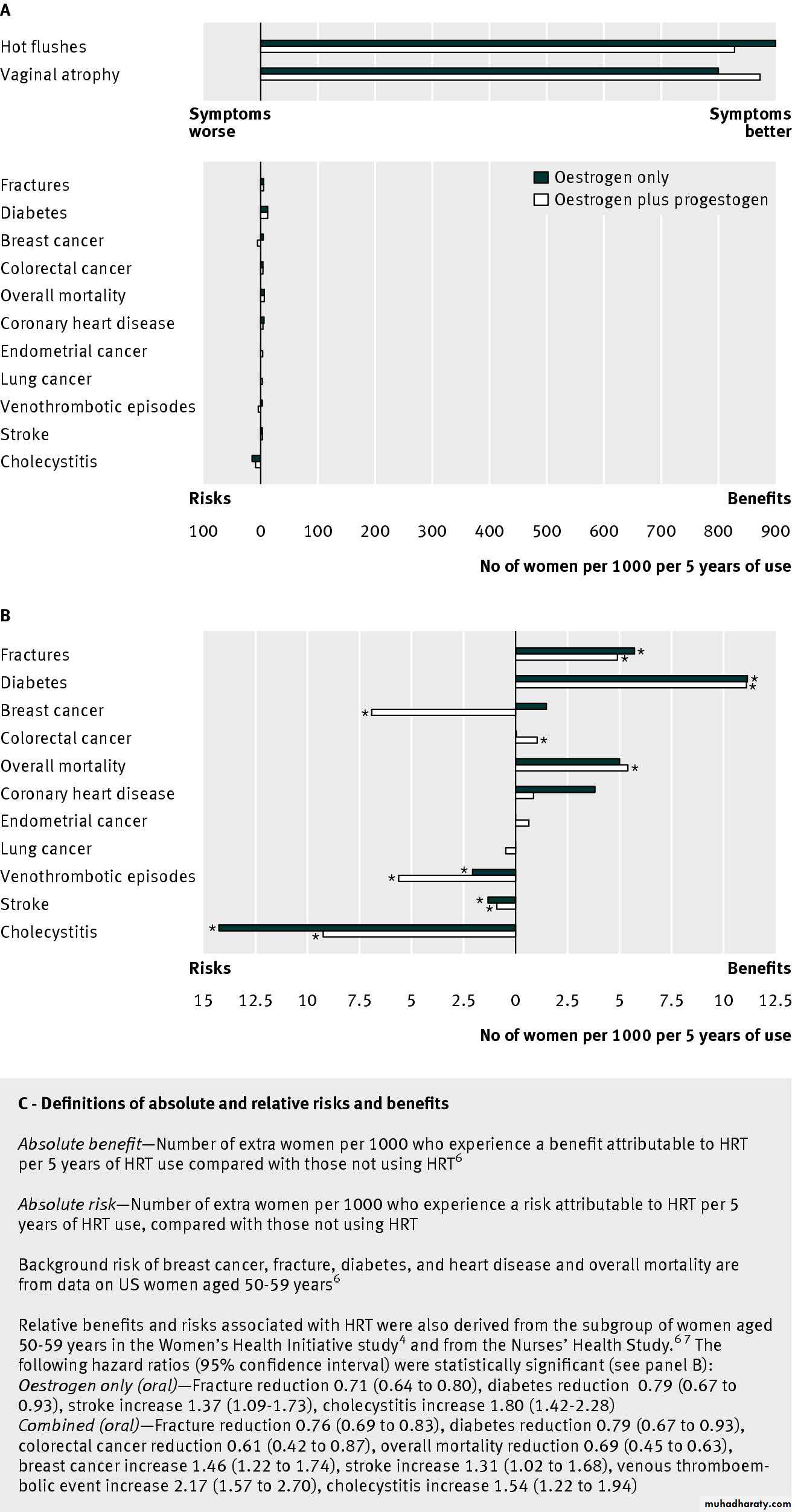

The figure⇓ provides the estimated absolute benefits

from HRT use in postmenopausal women aged 50-59 years or <10 years after menopause, based on background risk in American women, using data from the largest randomised controlled trial of HRT versus placebo to date (the Women’s Health Initiative study) and the prospective observational Nurses’ Health Study. HRT (oestrogen alone and combined) shows significant absolute benefit for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, and fracture reduction and for the prevention of diabetes.The relative efficacy of tibolone compared with conventional HRT is not well established. One large, multicentre randomised double blind controlled trial found that tibolone reduced hot flushes as much as low dose (1 mg) oral oestradiol in postmenopausal women aged 45-65 years.

Tibolone caused less bleeding in the first three months of treatment and less breast tenderness and may also improve sexual function.

Clinical indications for HRT

Current evidence based guidelines6 10-12 advise consideration of HRT for troublesome vasomotor symptoms in perimenopausal and early postmenopausal women without contraindicationsand after individualised discussion of likely risks and benefits.

Starting HRT in women over age 60 years is generally not recommended.

For women with premature (age <40 years) or

early (<45 years) menopause, current guidelines recommend HRT until aged 50 for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms and bone preservation. HRT reduces fracture risk, but increased risk of osteoporosis alone is not an indication for HRT.Similarly, although HRT may also improve mood and libido, these are not primary indications for treatment. Vaginal symptoms alone do not require systemic HRT and can be managed with local oestrogens.

How safe is HRT?

For most symptomatic women, use of HRT for ≤5 years is safe and effective. HRT is contraindicated in some women and may lead to adverse outcomes in others. There are currently no large randomised controlled trials of the benefits and harms of HRT in women around the normal age of menopause (50-59 years), which is when vasomotor symptoms are most troublesome.The figure⇓ shows the estimated risks associated with HRT use in postmenopausal women aged 50-59 years or <10 years after menopause. However, these data are derived largely from the subgroup aged 50-59 years in the Women’s Health Initiative Study4 and the Nurses’ Health Study.

The background risk of most adverse events linked with HRT increases with age, and risks will differ according to age and current health status.

Furthermore, the Women’s Health Initiative study used aregimen of oral conjugated oestrogen (Premarin) (with or without medroxyprogesterone acetate) versus placebo, and it is uncertain whether other preparations and delivery systems have similar effects.

The principal risks of HRT to consider are thromboembolic disease (venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism); stroke; cardiovascular disease; breast and endometrial cancer; and gallbladder disease.

HRT and thromboembolic disease

Oral HRT (combined oestrogen and progestogen, and oestrogen only) increases the risk of venous thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, and stroke. These risks increase with age and with other risk factors, such as obesity, previous thromboembolic

disease, smoking, and immobility. In younger (<60 years) healthy women the absolute risk of thromboembolic disease is low and mortality risks from venous thromboembolism are low.

The type, dose, and delivery system of both oestrogen and progestogen may influence the risk of thromboembolic disease—for example, a recent systematic review found that oral but not transdermal HRT increased the risk of venous thromboembolism. In a large prospective observational study,

low dose (≤1.5 mg oral, or ≤50 μg transdermal) oestradiol did not increase the incidence of venous thromboembolism in low risk populations.

In clinical practice, previous venous thromboembolism and high risk of venous thromboembolism

are contraindications for HRT. If HRT is used by women at increased risk of thromboembolic disease, a transdermal preparation and reduced oestrogen dose are preferred. In the absence of personal or family history, screening for inherited

thrombophilias is not indicated before starting HRT.

HRT and stroke

Overall, HRT increases the risk of stroke.16 Stroke risk increases with age and is rare in women under 60 years. The risk of stroke may be lower with transdermal HRT at doses of 50 μg or less, but this has not been shown in randomised controlled trials. In older women (>65 years) tibolone increases the risk of stroke.In clinical practice avoid HRT or tibolone in women at high risk of stroke.

HRT and cardiovascular disease

The relation between HRT and cardiovascular disease iscontroversial, but the timing and duration of HRT, as well as pre-existing cardiovascular disease, are likely to affect outcomes.

In the estimated risks for younger women (aged 50-59 years) (figure⇓), there was no statistically significant cardiovascular risk or harm for HRT. HRT is generally avoided in older women (>60), who are more likely to have established cardiovascular disease.

Subgroup analysis from larger trials suggests that

starting HRT in younger postmenopausal women may have afavourable effect on cardiovascular health, but the validity of this “timing hypothesis” has not yet been shown by appropriately designed studies. In those who start HRT at about age 50 yearsand continue beyond age 60 years the cardiovascular risks from HRT are unknown.

HRT and breast cancer

Combined HRT

Combined HRT (oestrogen plus progestogen) increases the risk of a breast cancer diagnosis or breast cancer mortality. The risk of breast cancer with tibolone is not established, but large observational studies suggest an increased risk.21 The Women’s Health Initiative study reported an excess breast cancer risk attributable to combined HRT of 8 per 10 000 women a year after four to five years of use. This equates to about a 0.1% increase in breast cancer.

Combined HRT also increases breast

density and the risk of having an abnormal mammogram.Oestrogen-only HRT

Data are conflicting over the risk of breast cancer with oestrogen-only HRT. In the Women’s Health Initiative study, conjugated equine oestrogen (Premarin) did not increase the risk of breast cancer for up to seven years of use in women who

had had a hysterectomy.

Most observational studies report

no increased risk for up to five years of use, but the large, observational Million Women Study showed an increased risk of breast cancer with oestrogen-only HRT at less than five years of use. Studies are consistent in showing a greater risk of breast cancer with combined HRT than with oestrogen alone.HRT and endometrial cancer

In women who have an intact uterus, unopposed oestrogen may lead to endometrial hyperplasia and increases the risk of endometrial cancer. For this reason women who retain their uterus and use oestrogen should also take progestogen.Combined continuous HRT does not increase the risk of

endometrial cancer provided that adequate duration and dose of progestogen are used, but sequential HRT may increase risk.

Tibolone does not increase the risk of endometrial hyperplasia or cancer.

HRT and gallbladder disease

Large randomised controlled trials have shown that HRT increases the risk of cholecystitis. Observational data (the Million Women Study) show that this risk may be reduced byusing transdermal rather than oral HRT, avoiding one cholecystectomy in every 140 users.

What are the precautions for HRT?

No consensus has been reached on absolute contraindications to HRT. However, on the basis of the above data, we advise avoiding or discontinuing HRT in patients with the following:

1• A history of breast cancer, as HRT may increase the risk of breast cancer recurrence and of new breast cancers.Tibolone also increases the risk of breast cancer

recurrence. Exclude breast disease and investigate any abnormalities before starting HRT. Counsel women

considering HRT that it may increase their risk of an

abnormal mammogram and that combined HRT may

increase their risk of breast cancer after four to five years of use.

2• A personal history or known high risk of venous or arterial

thromboembolic disease, including stroke andcardiovascular disease, as HRT may further increase risk.

Tibolone increases stroke risk in older women.18 If HRT

is prescribed, a transdermal preparation with minimal

oestrogen is preferred. In the absence of personal or family history, screening for inherited thrombophilias is not indicated before starting HRT.

3• Uncontrolled hypertension.

Other conditions that require caution with use of HRT include:

1• Abnormal vaginal bleeding. HRT should not be started inwomen with undiagnosed abnormal vaginal bleeding.

Combined HRT may often cause unscheduled bleeding in the first six months of use. Persistent or new onset (after six months) unscheduled bleeding on HRT requires investigation to exclude pelvic disease.

2• Abnormal liver function. Avoid oral HRT products since these are metabolised in the liver

3• Migraine. This does not seem to be exacerbated by HRT so migraine is not a contraindication, but low dose transdermal preparations may be preferable

4• History of endometrial or ovarian cancer. Seek specialist review before considering HRT

5• High risk of gallbladder disease. Advise that HRT may increase this risk further, although the risk may be lower with transdermal therapy.

How cost effective is HRT?

HRT is principally a treatment for menopausal symptoms, which veness difficult to measure. Modelling studies of quality of life years (QALYs) gained in the United Kingdom and the US have used data from the Women’s Health Initiative study and considered fracture reduction, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, coronary heart disease, stroke, and venous thromboembolic events over five years of HRT use.They show that HRT is cost effective in all women compared with no treatment but that the cost effectiveness was greater in those

with more severe vasomotor symptoms (UK data, estimated cost per QALY gained: £580 (€700; $920) for women with an intact uterus and £205 for women who had had ahysterectomy). However, this model did not include the cost investigating abnormal uterine bleeding with HRT or additional abnormal mammograms.

How is HRT taken and monitored?

Before HRT is started• Consider HRT in perimenopausal or recently

postmenopausal symptomatic women with low risk factors for cardiovascular or thromboembolic disease.

• Consider the nature and severity of menopausal symptoms

and their impact on function and quality of life, the

woman’s age and health status, as well as her wishes for treatment.

• It is reasonable to advise younger, healthy postmenopausal

women that HRT is unlikely to increase their risk ofcardiovascular disease. However, HRT is not currently

indicated in women at any age for preventing or treating cardiovascular disease.

• Discuss with women any modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such as alcohol, smoking, diabetes and hypertension control. Avoid prescribing HRT in women with established cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease or at high risk of these conditions. Calculate individual risk of cardiovascular disease .

• Consider HRT in those at high risk of fracture if there are

no contraindications. Calculate fracture risk using an online tool such as FRAX (www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX) and measure bone density with bone densitometry.

• Consider whether anxiety and/or depression may be

contributing to the symptom burden.29 Somatic symptoms of menopause, such as palpitations and sleep disorder, may be difficult to distinguish from those of depression and anxiety. HRT may reduce palpitations and improve sleep and may improve mood but is not a treatment for clinical anxiety or depression.• Individualise discussion of risk and benefit; written

information is helpful. Discuss other possible management options (see “Tips for patients” box).

• Ensure breast and cervical screening are up to date and

investigate any abnormal vaginal bleeding.Starting HRT

• Available HRT preparations vary between countries .

• Use the lowest effective dose of HRT for the minimum duration to control troublesome symptoms, as advised by most current guidelines.

• Perimenopausal women may need contraception. In those without contraindications, combined oral contraceptive preparations will treat vasomotor symptoms and reduce fracture risk.

• No clear consensus has emerged on whether oral or

transdermal therapy is first line, but transdermal may be preferable in those with risk factors for thromboembolic

disease or if oral absorption may be limited.

• Oestrogen alone should be used in women after

hysterectomy. The progestogen component of HRT maybe progesterone or a progestogen, which binds to the

progesterone receptor. Observational studies suggest that HRT products containing a micronised progesterone or dydrogesterone may be associated with a lower risk of breast cancer, cardiovascular disease, and thromboembolic events, but adequately powered randomised controlled trials have not yet been conducted.

• In perimenopausal women consider cyclic HRT or (in women under 50 years) low dose combined oral contraceptives to minimise irregular bleeding. In women who are one to two years postmenopausal and wish to avoid bleeding, consider continuous combined HRT or tibolone.

• Ensure that you discuss the patient’s expectations of

effectiveness. Some women are happy to achieve a lower level of symptom reduction to minimise side effects or hormone exposure.• Tailor the dosage and type of HRT to symptoms and

possible side effects. Start with a low dose oestrogen and consider gradually increasing the dose after four to six weeks if troublesome vasomotor symptoms persist.

Monitoring HRT

• Monitor effectiveness by improvement in symptoms (blood tests are rarely useful).• Mastalgia and irregular bleeding may respond to a

reduction in oestrogen dose.

• Unscheduled bleeding in the first six months of HRT use does not need investigation, but investigate new onset or persistent bleeding to exclude pelvic disease

• If vasomotor symptoms persist despite adequate absorption of oestradiol, investigate other causes of hot flushes or sweating.

• Review patients at least annually to evaluate indications for use, assess individuals’ risk and benefit profile, and promote lifestyle interventions to reduce or prevent chronic disease. HRT does not cause weight gain.

• The schedule for other screening tests such as

mammography and cervical smears is not altered by HRT use.

Continuing or ceasing HRT

Base the decision on whether to advise continuation of HRT onsymptoms and ongoing risks and benefits rather than a set

minimum or maximum duration of therapy. Cessation of HRT

leads to recurrent symptoms for up to 50% of women. Consider

the potential impact of recurrent symptoms on quality of life.

The risks of HRT may be related to duration of HRT use—for

example, the risk of venous thromboembolism is greatest in the

first year of use, but the risk of breast cancer increases with

duration of use. Most guidelines recommend using HRT for up

to four to five years. No clear consensus has emerged on how

to discontinue HRT, and symptoms may recur regardless of

whether HRT is stopped slowly or suddenly.

What are the alternatives to HRT for menopausal symptoms?

For hot flushes and night sweats

HRT is currently the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms.

• Effective non-hormonal preparations include

serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (paroxetine, fluoxetine, citalopram, and escitalopram).• Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors that induce

CYP2D6, particularly paroxetine and fluoxetine, should

be avoided in women who take tamoxifen as they may

interfere with the metabolism of tamoxifen.

• Gabapentin is the only non-hormonal product shown to be equally effective as low dose oestrogen for vasomotor symptoms.

• Clonidine is mildly effective

• Relaxation therapy, mindfulness based therapies, andcognitive behaviour therapy may improve vasomotor

symptoms. A recent systematic review showed no effect

for any other interventions (including acupuncture,

homeopathy, vitamin E, or magnetic devices) for hot

flushes after breast cancer.

• Overall, data from large randomised controlled trials do

not support the efficacy of black cohosh or other “natural

remedies” for the treatment of hot flushes.

• So called “bio-identical” hormones have not been shown

to be safe or effective.

For atrophic vaginitis

• Vaginal dryness can be effectively treated with topical oestrogen. Vaginal oestrogens can be used safely in the long term without additional progestogens.

Non-hormonal options for atrophic vaginitis include

lubricants and vaginal moisturisers, although there is little evidence to suggest they offer the sustained benefit associated with vaginal oestrogen.Tips for patients

• Hormone replacement therapy (or HRT) contains oestrogen to treat menopausal symptoms and, for women who have not had ahysterectomy, a progestogen to protect the uterus from cancer. Its risks and benefits have been extensively studied. HRT is a safe and effective treatment for most healthy women with symptoms who are going through the menopause at the average age (about 51 years)• Risks and benefits of HRT will vary according to age and other health problems.

• HRT is the most effective treatment in reducing the number and severity of hot flushes and night sweats at menopause. It may also improve sleep, joint aches and pains, and vaginal dryness. HRT protects against fractures resulting from osteoporosis

• HRT is also recommended when menopause occurs in women younger than 45 years until aged 50 who do not have any other conditions that might mean HRT is not suitable for them

•The effects of tibolone are similar to those of HRT, but less is known about the risks and benefits of tibolone

•Other effective treatments for hot flushes and night sweats include some antidepressants and gabapentin, a drug also used for chronic

pain

• Relaxation, meditation, and cognitive behavioural therapy may also be helpful

• When vaginal dryness is the main problem, only vaginal oestrogen has been proved effective, but vaginal lubricants and moisturisers

may also be helpful

• Discuss with your doctor your expectations of treatment. Higher doses of HRT may be more effective in reducing symptoms of hot

flushes but may also confer greater risk. Using the lowest dose for the shortest effective time is the current approach to treatment

• Discuss ongoing use of HRT yearly with your doctor. HRT does not change the usual frequency of cervical smears and mammogram screening.

Estimated benefits and risks of oral HRT in postmenopausal women aged 50-59 years, or <10 years after menopause.

Panel B shows more clearly the data in the lower part of panel A. Asterisks indicate statistically significant hazard ratios (P<0.05)

Hormone therapy for menopausal symptoms

BMJ 8 February 2012recently published and much publicised paper by Shapiro and colleagues, the last in a series of four, evaluated the effects of hormone therapy on the risk of breast cancer. The authors of the four review articles applied epidemiological principles to

the findings of two randomised placebo controlled studies from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI; 27 347 women) and two observational studies—the Collaborative Reanalysis (53 865 women) and the Million Women Study (MWS). Shapiro and colleagues concluded in their fourth paper that the MWS had

design defects, that it contained multiple biases, and that its findings were thus not robust enough to show that hormone therapy increased the risk of breast cancer.

All observational studies are inherently biased because subjects are not randomly assigned to treatment or control. Adjustment for confounders and careful design of observational studies help to reduce bias. However, because there is no independent variable, such studies can tell us only about association not causation.

The MWS was published in the Lancet in August 2003,2 and aflurry of letters was published in a print issue later that year,many of which raised the same concerns about bias recently highlighted by Shapiro and colleagues. The authors of the MWS replied and the sequence continued over the years: concerns about the believability and worry about uncritical acceptance of the MWS data, followed by more responses from the authors of the MWS.

Although observational studies add to our knowledge, they cannot replace randomised trials. Analysis of data from the WHI found a decreased risk of early stage breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in women randomised to receive oestrogen only.

Subgroup analysis showed that the reduction in breast cancer was statistically significant only for women who complied with treatment, had not used hormones before study entry, and had started oestrogen more than five years after the menopause.

No benefit was seen for women who started oestrogen treatment at the time of the menopause.8 This “gap time concept” of areduced risk of breast cancer only if oestrogen is started late contrasts with the gap time hypothesis of a potential decrease in cardiovascular disease if oestrogen is started early. Shapiro and colleagues’ evaluation of the WHI findings concluded that treatment with oestrogen only does not increase the risk of breast

cancer and may even reduce it, although the last possibility is based on statistically borderline evidence.

Fewer breast cancers were diagnosed in the first four years of follow-up in women in the WHI who were randomised to receive combined oestrogen

and progestin. This is thought to be the result of hormonally induced increased density of breast tissue, which leads to delayed mammographic diagnosis of cancer. After four years, breast cancer rates were higher in women on combined hormone therapy, and diagnosed cancers were larger and more advanced.

Women who had used hormone treatment before joining the study were at higher risk of breast cancer than those who were treatment naive, but a significant increasing trend in risk of breast cancer over time was seen for this last group.

Pretreatment clinical or laboratory characteristics may be discovered that will help identify women who, because of genetic predisposition, are at increased risk of adverse events with hormone treatment.

The role of progestogens in the development of breast cancer needs to be clarified. A recent

review suggests that women who use progesterone or dydrogesterone instead of progestogens have a lower risk of breast cancer.

Because treatment with oestrogen alone seems

to be associated with lower risk, local delivery of progestogen to the endometrium is a potential option. However, a recent case-control study found increased odds of breast cancer in women with a levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Other strategies to deliver combination treatment are being investigated; oestrogen combined with selective oestrogenreceptor modulators has the potential to improve symptoms without affecting the breast and has positive effects on lipids and bone.

How should we advise women while we wait for better treatment solutions?

The second article in Shapiro and colleagues’ seriesconcluded that potential biases in the combined hormone treatment arm of WHI reduced the robustness of an association between treatment and breast cancer.

However, they acknowledged that the use of oestrogen plus a progestogen could possibly increase the risk of breast cancer. This is how most clinicians would frame the issue when discussing the risks of using combined hormone treatment.

The increased risk of breast cancer associated with use of combined oestrogen-progestogen (hazard ratio 1.24) is similar to risks conferred by delayed

menopause or moderate use of alcohol. Although an increase in risk of this size may be important for public health, individual women may not consider it enough to change their minds about using hormone treatment.

Women should continue with regular breast screening, and those with dense breast tissue may need more frequent screening.

The primary aim of the WHI was to see if the use of hormone treatment decreased heart disease, as observational studies had found. The study was not designed to determine the risks of hormone use for symptoms in early menopause. It was not

powered for subgroup analysis in the 50-59 year age group, and numbers of adverse events were small. Healthy women have alow absolute risk of adverse events, whether they use hormone treatment during early menopause or not.

July 13, 2012 (Penrith, Australia) — A large new study of over 40 000 postmenopausal women has found that use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is associated with an increased risk of high blood pressure [1]. The results also show, for the first time, that the risk of hypertension rises with longer duration of HRT use, say Dr Christine L Chiu (University of Western Sydney, Penrith, Australia) and colleagues in PLoS One.

And importantly, "the association between using HRT and high blood pressure was more prominent for younger postmenopausal women, aged 45–55 years," senior author Dr Joanne M Lind (University of Western Sydney) told heartwire . "By the time women reached their 70s, the impact was not significant anymore."

Heartwire © 2012 Medscape, LLC

Lind notes that it is "still only an association, we don't know the direct cause. But we do know that of the women who'd used HRT, more of them had high BP compared with the women who'd never used it. We recommend that doctors take into consideration the fact that HRT could increase the odds of having high BP and if possible minimize the length of time that women take it." She and her fellow authors also recommend that BP should be closely monitored both during and after use of hormone therapy, and that women be made aware that hypertension is a possible risk of HRT use.

Risk of Hypertension Rose With HRT in Younger Women

Most of the studies conducted to date have focused on the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke from HRT, and of those studies that have investigated the relationship between HRT and blood pressure, the findings have been largely inconsistent, Chiu and colleagues state in their paper. Using data from the 45 and Up Study of healthy aging, which Lind notes is the "largest of its kind in the Southern hemisphere," they set out to ascertain the association between HRT use and hypertension, and whether the number of years spent taking HRT was associated with risk.A total of 43 405 postmenopausal women, average age around 63 years, were included, all of whom had an intact uterus, had gone through menopause, and had not started HRT and did not have hypertension prior to menopause. Of the 12 443 women who had used HRT (past or current), 20% self-reported having high BP compared with 17% of the 30 962 women who had never used it.

The researchers note they could not account for the different types of HRT taken by women in the study, as that information was not available.

After adjusting for demographic and lifestyle factors, odds ratios for the association between HRT use and hypertension was 1.59 for those <56 years, 1.58 for those aged 56–61 years, and 1.26 for those aged 62–70 years. Women who had used HRT at any time were first diagnosed with hypertension 2.8 years earlier than women who had never used it.

"In that younger age group, any length of time they took HRT was associated with higher odds [of hypertension], and those odds just kept on increasing the longer a woman had taken it," Lind noted adding, "no one has shown that before."

But as women got older, the association between HRT use and hypertension diminished, she adds.

Longer Follow-Up Needed

Lind says some of the older studies that examined HRT and BP even found a slight reduction in BP in women who taking such therapy "but they haven't looked at the long-term effects," she says, adding that this information is sorely needed."A clinical trial of HRT, which includes an extended period of follow-up after cessation of treatment, is required to decipher how HRT leads to higher odds of having high blood pressure. Such a trial should initiate HRT close to menopause and only include women who have never used HRT previously," she and her colleagues conclude.

Hormonal Contraceptives and Arterial Thrombosis

Not Risk-free but Safe Enough

Diana B. Petitti, M.D., M.P.H.

The link between combined estrogen–progestin

oral contraceptives and venous and arterial thrombosis

was made soon after these products were

marketed, in the early 1960s.1-3 By 1970, the doses

of estrogen in combined estrogen–progestin oral

contraceptives had already been lowered on the

basis of epidemiologic data showing that formulations

with higher estrogen doses were associated

with increased vascular risks.

nejm. org june 14, 2012

Studies published in 1995 and 1996 showed that increases in the risk of venous thromboembolism were greater with newly marketed estrogen–progestin oral-contraceptive formulations containing desogestrel and gestodene than with formulations containing levonorgestrel and other “older” progestins.

5-8 Much attention has since been paid to

estimating the comparative cardiovascular risks

associated with hormonal contraceptives, with a

focus on possible differences in risk among progestins.

In this issue of the Journal, Lidegaard and colleagues

report the results of their cohort study of hormonal contraceptives and arterial thrombotic events (thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction). The study encompasses data from the entire population of Danish women, 15 to 49 years of age, for the period from 1995 through 2009. With more than 1000 strokes and almost 500 myocardial infarctions in current users of hormonal contraceptives, the study is 10 times as large as a recently reported study in the United States that also assessed the comparative risks of arterial thrombotic events among users of hormonal contraceptives.The study by Lidegaard and colleagues showed

that the relative risks of thrombotic stroke and

myocardial infarction were increased by a factor

of 1.5 to 2 among users of estrogen–progestin

oral contraceptives with a low dose of ethinyl estradiol (30 to 40 μg) for all the progestins studied

(norethindrone, levonorgestrel, norgestimate,

desogestrel, drospirenone, and cyproterone acetate).

In a comparison of such low-dose formulations

with different progestins, the relative risksof thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction

were statistically indistinguishable. For estrogen–

progestin oral formulations containing a very

low dose of ethinyl estradiol (20 μg), the study

showed that the relative risks of thrombotic

stroke and acute myocardial infarction were increased by a factor of approximately 1.5 when formulations containing desogestrel and gestodene

were used, as compared with nonuse.

Among users of the vaginal ring and the transdermal patch, which are combined estrogen–progestin formulations, the relative risks of thrombotic stroke were 2.5 and 3.2, respectively. Although these relative risks are higher than the relative risks of thrombotic stroke among users of the other low and very low doses of ethinyl estradiol in the combined estrogen–progestin hormonal contraceptives studied, the increases are statistically indistinguishable. The relative risks of thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction were notsignificantly elevated for any of the progestinonly formulations studied.

Among Danish women who did not use hormonal

contraception, the absolute risks of cerebral thrombosis and myocardial infarction were low. Considering the absolute risks of cerebral thrombosis and myocardial infarction among nonusers of hormonal contraceptives and the relative risks among users, the number of “extra” arterial thrombotic events attributable to hormonal contraceptives is about 1 to 2 per 10,000women per year or, equivalently, 10 to 20 per

100,000 women per year for the combined estrogen–

progestin formulations that might cause arterial events. These are small numbers. For an individual woman, the probability of an event is quite small.

Venous thromboembolic disease is more common

than arterial vascular disease in women of

reproductive age. Arterial vascular disease is potentially a greater threat to an individual woman

because the sequelae are more serious.

Stroke in particular can lead to severe and permanent disability.

Although not explicitly stated in regulatory and other discussions, a large excess in the relative risk of stroke in the comparison of one hormonal contraceptive with another could, and probably should, have an important influence on the conclusion about the overall risk–benefit

ratio of the formulation, as compared with other

formulations that have equal contraceptive

effectiveness. None of the hormonal contraceptives

studied by Lidegaard and colleagues were

associated with an excess risk of stroke that was

unacceptable, considering their contraceptive

and noncontraceptive benefits.

Women, their physicians, and the public should be reassured not only by the Danish study but

by the vast body of evidence from epidemiologic

studies of hormonal contraception that have

been done over the past five decades. This body

of research documents the small magnitude of

the problem of arterial thrombotic events in

women using combined estrogen–progestin hormonal

contraceptives.

The research shows that the small risk could be minimized and perhaps eliminated by abstinence from smoking and by checking blood pressure, with avoidance of hormonal contraceptive use if blood pressure is raised. With the addition of the Danish data, evidence is now even stronger that progestinonly formulations of hormonal contraception

have vascular risks that are undetectable with

modern epidemiologic methods.

Although hormonal contraception is not risk-free, the evidence is convincing that the low and very low

doses of ethinyl estradiol (<50 μg) in the combined

estrogen–progestin contraceptives studied

by Lidegaard and colleagues — whatever the progestin and whether delivered orally or by means

of the patch or the ring — are safe enough.