Pregnancy in high risk cardiacconditions

Heart 2009د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2011

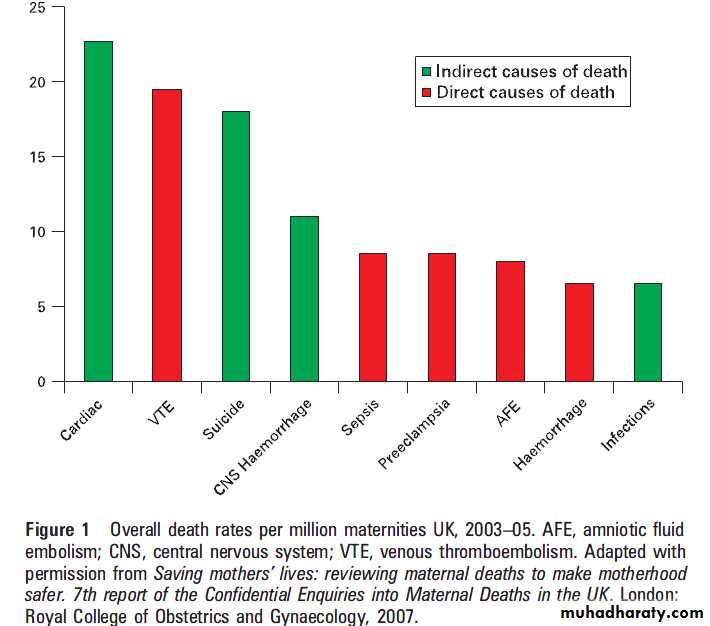

Heart disease is present in 0.5–1% of all pregnant

women and is the biggest killer of pregnant womenin the developed world .Surprisingly, there

have been no signs of decline in this incidence over

the past two decades .In the UK, all

maternal deaths (during pregnancy and within

the first post partum year) are recorded and

examined in detail every 3 years.

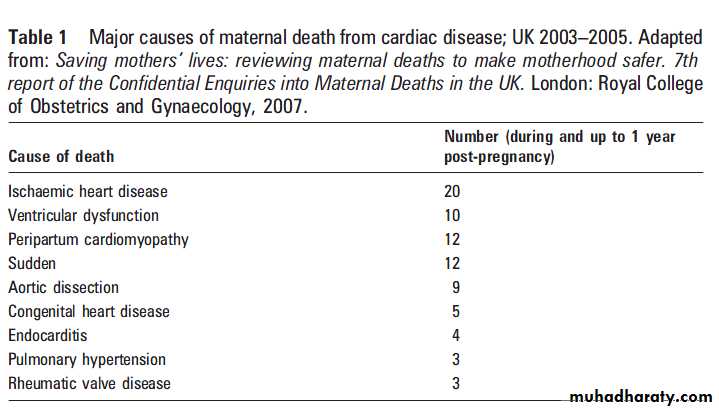

Of the maternal cardiac deaths reported for the 2003–5 triennium, more than half were due to coronary artery disease, puerperal cardiomyopathy and aortic dissection (table 1).

As in previous triennial reports, substandard

care continues to be an important factor,

and contributed to the woman’s death in more

than a third of cases.

These conditions often present acutely and

catastrophically in women with no known preexistingdisease. Rapid recognition of the acute

presentation and appropriate management will

improve their chances of survival.

In addition, identifying risk factors for these conditions should flag up at risk patients for targeted ante- and postnatal care.

Modifiable risk factors such as obesity and smoking appear particularly important for this

group of women and are a growing public healthproblem. In addition, social deprivation and

immigrant status are significant risk factors for

maternal deaths of all causes, including heart

disease, underscoring the need to improve access

to health care for these vulnerable groups.

ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES AND ISCHAEMIC

HEART DISEASE

Death from ischaemic heart disease

Maternal deaths from acute coronary syndromes

(ACS) and ischaemic heart disease (IHD) rose four

fold in the triennium from 2000–2 to 2003–5. This

increase is one of the main reasons why cardiac

disease remains the single largest cause of UK

maternal death, accounting for nearly a quarter of

cardiac deaths.

There were 16 deaths from acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Of these, nine were

due to atherosclerosis, four to coronary arterydissection, and one was embolic. Only four late

deaths (42 days to 1 year postpartum) were

reported; this is almost certainly an underestimate,

since the obstetric services whose duty it is to

inform CEMACH (Confidential Enquiry into

Maternal and Childhealth) of pregnancy related

deaths are unlikely to be informed of admissions

for ACS that occur months after delivery.

There were an additional four deaths from heart failure

secondary to atherosclerotic IHD. This spread of

pathologies causing AMI is a reflection both of the

pregnant state and of the cardiovascularly

unhealthy lifestyle led by some women in the

UK. Coronary artery dissection is an uncommon

but recognised complication of pregnancy.

Like aortic dissection, it can occur in pregnancy and the puerperium in the absence of risk factors other

than the hormonal changes of pregnancy.

It is salutary to note that although there was no known pre-existing heart disease in those who died from AMI, every woman who died had identifiable risk factors.

The main risk factors were older age and obesity. The mean age of women dying of myocardial infarction was 35 years, and more than

a third were morbidly obese (body mass index

(BMI) >35). Smoking, hypertension, type II

diabetes and poor antenatal attendance were other important risk factors.

Outcome of acute coronary syndromes in

pregnancyAMI remains an uncommon event, and is estimated

to have occurred in 6.2 per 100 000

deliveries in the USA between 2000 and 2002.

However, pregnancy itself is a risk factor for AMI,

increasing the risk 3–4 fold compared with the

non-pregnant state. Maternal age is a further

factor, with the risk of pregnancy related AMI

being 30 fold higher in women over 40 years

compared to those under 20 years of age.

AMI is currently under investigation by the UK Obstetric

Surveillance System (UKOSS), an organisation

that prospectively investigates selected rare conditions

in pregnancy, to establish the incidence and

outcome.

The risk of death from AMI in pregnancy has been reported to be as high as 37%, but recent

data from the USA suggests the risk to be lower, at

around 5%.

There are several possible explanations for this apparent improvement in survival.

Strategies to identify and treat acute coronarysyndrome in general have improved, with emphasis

on rapid thrombolysis and the development of

widespread primary percutaneous intervention

(PCI). The latter may be of particular benefit to

pregnant women, both because lifesaving thrombolysis

may be withheld for fear of causing haemorrhage, and because PCI is the only effective treatment when the pathology is coronary artery dissection.

An alternative explanation of the apparent

improvement in mortality is that older definitions of AMI only included those with ST elevation;newer definitions are more inclusive and encompass

patients who are likely to have a better

prognosis.

Nonetheless, mortality remains higher than that of the non-pregnant population, and the 2003–5 CEMACH report identified substandard care in around a third of cases.

The most common problems were failure to recognise the symptoms of ACS or ECG changes by the obstetric team and,where rapid PCI was unavailable, withholding of thrombolysis in the face of a large ST segment elevation AMI, because of the risk of bleeding. In the latter situation a balance of risk must be made

between treating an extensive AMI and the risk of

bleeding—a team decision that has to involve

senior obstetric and cardiology staff.

Chest pain in pregnancy is common and may simply be asymptom of heartburn; however, it should never

be ignored as it may also represent AMI, pulmonary

embolism or aortic dissection.

Urgent cardiac review is always appropriate if a pregnant or postpartum woman presents with significant chest pain.

Of note,

troponin is not affected by pregnancy.

Management of ACS in pregnancy and the

puerperiumAs for all life threatening conditions in pregnancy,

the principle of management should be the same as for non-pregnant patients. ACS is one condition

where the mother should be treated first, before

the baby is delivered, whatever the gestational age,because the risk of delivery with an untreated ACS is so high.

Close liaison with the obstetric team is needed in order to monitor the wellbeing of the fetus and plan continuing antenatal or postnatal care.

Urgent PCI is the treatment of choice and consideration must be given to the type of stent deployed.

As a general rule, bare metal stents should be used in preference to drug eluting stents because the risk of stent thrombosis is likely to be lower when clopidogrel has to be stopped in order to avoid major bleeding at the time of delivery.

Aspirin should always be continued. Ideally clopidogrel should be continued for 6 weeks post-stent implantation, then stopped for a week before

delivery and restarted as soon as possible postpartum. Inevitably, there will be situations when

this practice cannot be followed; the cardiologist

and obstetrician must make an individualised joint

plan on the least risky approach.

There are only a handful of case reports on the

use of clopidogrel and small molecule glycoproteinIIb/IIIa receptor antagonists in pregnancy; they

indicate good maternal and fetal outcome, but no

conclusions on safety may be drawn from these

case reports.

The fetal radiation dose from PCI is low; if the maternal back and abdomen are protected and the field size coned down to the area of interest, the increased risk to the fetus of

dying of cancer within 15 years from 60 min

screening in the anteroposterior (AP) projection is

,1:80 000 (data derived from local radiation

protection team for actual case).

As for all procedures that require a pregnant woman to lie prone, a wedge should be placed under the right hip to prevent uterine compression of the inferior vena cava. There are little data on the use of thrombolysis for myocardial infarction in pregnancy; however, the complication rate for thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism in pregnancy is only 1%.

Therefore, if timely PCI is unavailable it is

unreasonable to withhold thrombolysis from a

pregnant woman who presents with an anterior or

anterolateral ST segment elevation AMI. If the

coronary arteries are found to be normal in the face

of an apparent ACS, coronary spasm or embolism

should be considered and infarction imaging

performed to seek evidence of myocardial damage.

Coronary artery bypass grafting in pregnancy

There are few reports of the use of coronary arterybypass grafting in pregnancy.

Maternal mortality from cardiopulmonary bypass surgery is up to 13% and the risk of

fetal loss is 30%.

Medical management of coronary artery disease in

pregnancyAddressing risk factors such as obesity, smoking,

hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes is particularly important in this group of young patients

who remain at continuing risk of further premature

cardiac events.

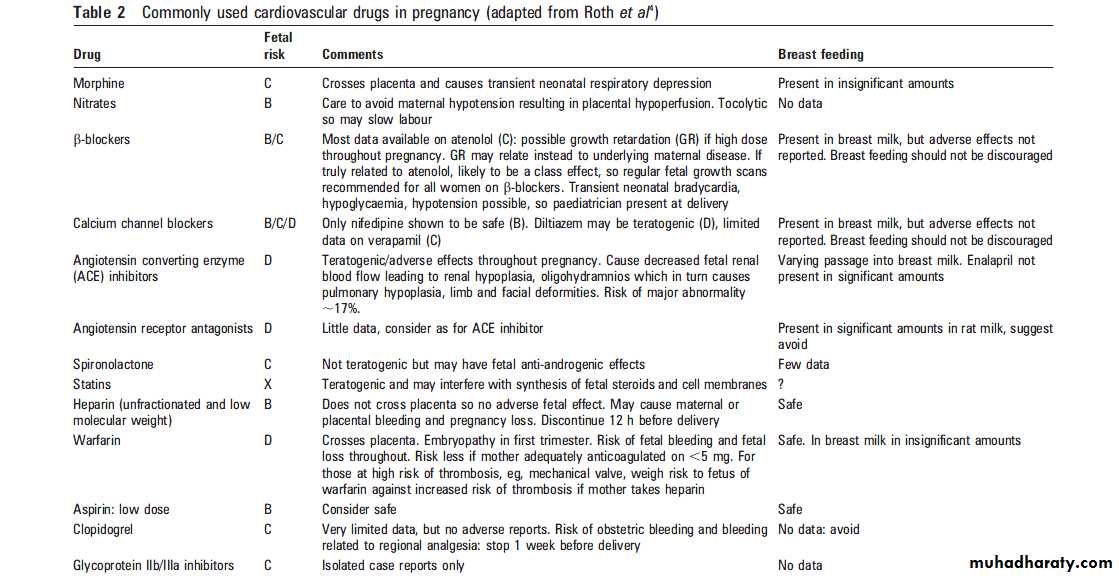

There are little data on the use of many cardiac drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding,so the risks to the fetus may be unknown, and the risks and benefits must be considered on an individual basis (table 2).

As a general principle drugs should be avoided in pregnancy. However, effective treatment or prevention of a life threatening condition should not be withheld. The rise in pregnancy related deaths from

coronary artery disease is a particularly worrying

trend. At first sight it is at odds with the decline in

coronary mortality seen in the developing world

for the past 30 years—a decline that is largely due

to a reduction in risk factors.

However, in the UK and other countries, there has been a slowing in the reduction of coronary deaths in recent years. This, together with the rise in pregnancy related

coronary deaths in women with cardiovascular

risk factors, may mean that we are due to see

coronary deaths among the general population

again reaching epidemic proportions.

PERIPARTUM CARDIOMYOPATHY

Peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) may be consideredas a subset of dilated cardiomyopathy, since

the clinical and pathologic presentation of PPCM is

similar to that of other types of dilated cardiomyopathy.

Its relationship with a (previous) pregnancy

and the long term prognosis discerns this disorder

from other forms of dilated cardiomyopathy.

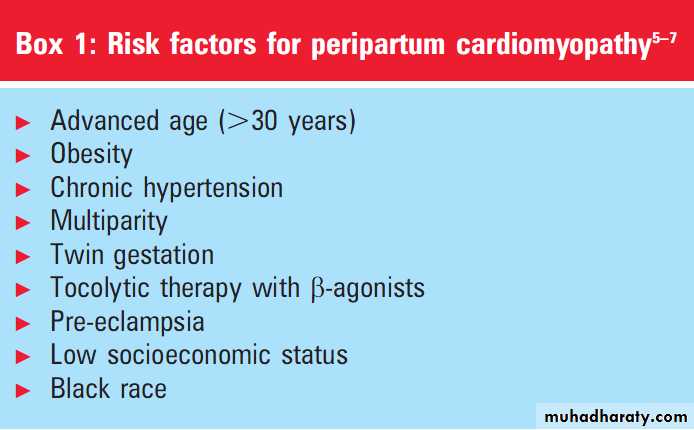

The incidence of PPCM is very variable throughout the

world and ranges from 1 per 3000 to 1 per 4000 live

births. Risk factors for PPCM are listed in box 1. It

is most likely, however, that PPCM is multifactorial.

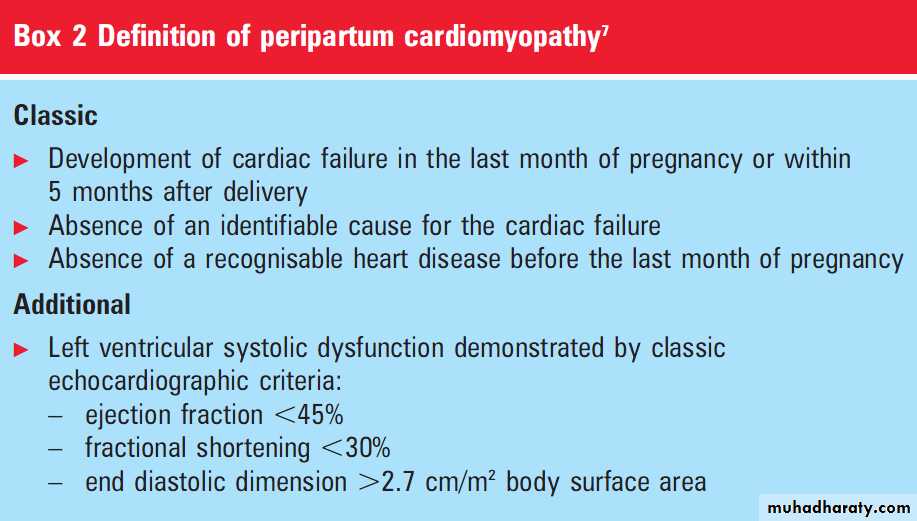

Although the diagnosis of PPCM is one of exclusion, the diagnosis of PPCM is made on the basis of classic and additional signs: timing of the first appearance of the disease and a combination of specific (newly developed) echocardiographic findings (box 2).

The differential diagnosis includes myocardial infarction, severe pre-eclampsia, sepsis, amniotic fluid embolism and pulmonary embolism.

It seems very important, especially with respect to

the prognosis of future pregnancies, to exclude

known causes of heart failure such as pregnancy

induced hypertensive disorders as a cause for PPCM.

Aetiology of PPCM

The aetiology of PPCM is still obscure. It is unlikely that it represents a clinically silent underlying cardiomyopathy that is unmasked by thehaemodynamic stress of pregnancy. A number of

possible causes have been postulated: myocarditis,

abnormal immune response to pregnancy, maladaptive

response to the haemodynamic stress of

pregnancy, accelerated myocyte apoptosis, stress

activated cytokines, viral infection, excessive prolactin

production, abnormal hormonal function,increased adrenergic tone, myocardial ischaemia, malnutrition and prolonged tocolysis. Cases of familial PPCM have also been described.

Management of PPCM in pregnancy and the

puerperium

In general, treatment of PPCM is similar to that of

other forms of congestive heart failure, reducing

afterload and preload and increasing contractility.

This involves salt and fluid restriction, the use of

diuretics to reduce volume overload, and antihypertensive medication to decrease afterload.

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

are contraindicated during pregnancy; their use isoccasionally justified if the benefit to the mother

outweighs the risk to the fetus (table 2). Therefore,

during pregnancy, hydralazine and nitrates can be

used in combination with digitalis and a-blockers.

Postpartum, ACE inhibitors can be added.

Patients unresponsive to oral therapy may be treated with dobutamine, dopamine, and nitroprusside.

Arrhythmias should be treated according to the

usual protocol.

Women with PPCM show a high incidence of thromboembolism.

Anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparins should be considered (twice daily injections—for example, enoxoparin 1 mg/kg twice daily).

The use of immunosuppressive drugs is still under debate. Azathioprine and corticosteroids have both been used in PPCM. Some state that this medication

should only be used after proven myocarditis in

endomyocardial biopsies.

Techniques like intra-aortic balloon pump or

ventricular assist devices may be used as a bridge to heart transplantation. Since more than half of

women with PPCM die suddenly, the aggressive

use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators

(ICDs) for primary prevention is warranted.

Delivery of women with PPCM

Unless cardiac failure cannot be treated adequately,pregnancy is allowed to proceed to term. Mode of

delivery depends on the maternal haemodynamic

situation and obstetric factors. Women with

adequate cardiac output may tolerate induction

of labour and vaginal delivery.

Prognosis of PPCM

The prognosis of PPCM has improved in recentyears due to better medical therapy. Despite this,

the long-term prognosis is still strongly related to

the recovery of ventricular function. More than

80% of all women with PPCM recover partially or

completely. Approximately 20% die or survive due

to cardiac transplantation.

Based on the ejection fraction at initial diagnosis, a prognosis for long term maternal outcome may be given. Women with an ejection fraction of ≤25% were very likely to receive a heart transplant in subsequent years. Asubsequent pregnancy influenced this negatively.

In women with an ejection fraction >25%, none of the women ended in end stage cardiac disease.

This was also the case after pregnancies in this group of women.

Recurrence of PPCM in a subsequent pregnancy

Strongly dependent on the severity ofPPCM in the index pregnancy and whether left

ventricular systolic function was normal at the

beginning of the subsequent pregnancy.

With an ejection fraction >25% at initial diagnosis of

PPCM, the recurrence rate in a subsequent

pregnancy is 20%. An abnormal ventricular function

at the beginning of pregnancy doubled the

incidence of PPCM to 40%.

AORTIC ANEURYSM, DISSECTION AND

PREGNANCYAortic aneurysm

The overall incidence of thoracic aortic aneurysm is

estimated to be around 6 per 100 000 patient years,

with males being affected 2–4 times more often

than females. The location of the aneurysms is

most often the ascending aorta (60%), followed by

aneurysms of the descending aorta (30%), whereas

arch aneurysms and thoracoabdominal aneurysms

occur less frequently. There are several heritable

disorders that affect the thoracic aorta, predisposing

patients to both aneurysm formation and

aortic dissection including

Marfan syndrome,

bicuspid aortic valve,

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome,

and familial forms of aortic dissection, aneurysm,

or annuloaortic ectasia.

Impact of pregnancy

During pregnancy, important maternal cardiovascularchanges occur, such as an increase in blood

volume, heart rate, stroke volume, cardiac output,

left ventricular wall mass, and end diastolic

dimensions, which starts as early as the fifth week

(fig 3). In addition, hormonal changes occur

which lead to histological changes in the aorta.

Fragmentation of the reticulum fibres, a diminished

amount of acid mucopolysaccharides, and

loss of the normal configuration of elastic fibres

have been observed in the aortic wall of pregnant

patients. So, both haemodynamic and hormonal

mechanisms have been suggested to play an

important role in the increased susceptibility to

dissection in women during pregnancy.

Dissection occurs most often in the last trimester of pregnancy or the early postpartum period. In all

women with enlarged aortic root diameters, the

risks of pregnancy should be discussed before

conception.

Women with previous aortic dissection are at high risk of aortic complications during pregnancy.

Counselling is very important in all patients with known aortic pathology.

Unfortunately, not all patients with aortic pathologyare aware that they are at risk. Therefore,

women with a family history of Marfan syndrome

or other familial aortic pathology should also have

counselling with a complete evaluation including

imaging of the entire aorta before pregnancy.

Marfan syndrome

Marfan syndrome, with a prevalence of 1 per 5000,

is the classical disorder associated with cystic

medial degeneration of the ascending aorta. It is

caused by mutations in the gene that encodes

fibrillin-1, resulting in both a decrease in the

amount of elastin in the aortic wall and a loss of

elastin’s normally highly organised structure.

Women with a normal aortic root diameter have

1% risk of aortic dissection or other serious cardiaccomplication during pregnancy.

When the aortic root diameter exceeds 4 cm the risk of dissection increases to 10%.

The Canadian guidelines

recommend that women with an aortic root

diameter >44 mm should strongly be discouraged

from becoming pregnant; the European guidelines

discourage pregnancy above an aortic root diameter of 40 mm.

There are still insufficient data available on pregnancy in women with Marfan syndrome with aortic root diameters >45 mm.

The risk is lower for pregnancy following elective

aortic root replacement.

Bicuspid aortic valve

Approximately 50% of young men with normally

functioning bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) have an

aortic dilatation. Ascending aortic specimens from

BAV patients have significantly less fibrillin-1

compared to patients with tricuspid aortic valves.

Furthermore, the aortic aneurysms of those with

BAV have more lymphocyte infiltration and smooth muscle cell apoptosis, suggesting degenerative changes similar to those found in Marfan patients.

Although patients with Marfan syndrome

are at a higher risk of aortic dissection compared to BAV patients (44% vs 6%), BAV isresponsible for more cases of aortic dissection (14%

vs 6–9%) due to its higher incidence in the general

population (1%). No data on pregnancy are

available. It is suggested to use the same guidelines

as for Marfan patients, but this is controversial.

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

Aortic involvement occurs almost exclusively inEhlers–Danlos type IV which is transmitted as an

autosomal dominant trait. The incidence of this

disorder is estimated at 1 in every 5000 to 20 000

live births. During pregnancy women may show

increased bruising, hernias, varicosities, or suffer

rupture of large vessels.

Aortic dissection may occur without dilatation. The course of pregnancy should be closely monitored. Guidelines for elective intervention have not been established because the operative risk in these patients is so high.

Management of aortic dilatation in pregnancy

All patients with aortic pathology should bemonitored by echocardiography at 6–8 week intervals throughout the pregnancy and for 6 months

postpartum.

Each pregnancy should be supervised by a cardiologist and obstetrician who are alert to the possible complications.

Patients with aneurysms of the aorta are often

treated with b-blocking agents, to decrease thedetrimental impact of systole on the aortic wall.

The effectiveness of this treatment is largely

unproven and somewhat controversial, but it has

become standard practice.

The original evidence is based on a small number of Marfan syndrome patients followed for a long period of time.

These data are not directly applicable to those with BAV or others without the Marfan syndrome. Fetal

growth should be monitored when the mother is

taking b-blockers. A recent mouse study demonstrated

that AT1 antagonists are very promising,

exerting their effect by reducing transforming

growth factor-b signalling. However, AT1

antagonists are contraindicated during pregnancy.

Surgical management of aortic dissection and

aortic aneurysm

Chest pain in pregnancy is commonly due to

gastro-oesophageal reflux, but may represent dissection, myocardial infarction or pulmonary embolism—acute life threatening conditions must be

excluded. Transthoracic echocardiography may

show dissection, but urgent computed tomography

or magnetic resonance imaging must be performed.

Aortic dissection in pregnancy is a surgical emergency;

senior cardiothoracic, cardiology, obstetricand anaesthetic consultants must act rapidly to

deliver the fetus (if viable) by caesarean section in

cardiac theatres and proceed directly to repair of

the dissection. The risk of obstetric bleeding due to

anticoagulation during cardiopulmonary bypass

must be weighed against the risk of delaying repair

of the dissection for a few hours post-delivery.

Repair with a composite graft or replacement with

a homograft avoids the need for long term anticoagulants.Pre-pregnancy surgery is recommended if aortic

root enlargement (>4.5 cm, or less in patients with

a low body surface area) is known in a Marfan

syndrome patient or in a patient known to have a

bicuspid aortic valve.

Elective aortic root replacement can be performed with very low morbidity and mortality. When dilatation of the aorta is discovered during pregnancy or progressive dilatation occurs during pregnancy, before 30 weeks of gestation, aortic repair with the fetus in utero is recommended. The risks of surgery for the mother during pregnancy are not much higher than outside pregnancy, but the risks for the fetus are

considerable with a mortality rate of 10–22%.

High flow, high pressure normothermic perfusion and a

perfusion index of 3.0 during cardiopulmonarybypass is probably safest for the fetus.

Hypothermia decreases placental blood flow and

may cause fetal bradycardia, leading to intrauterine

death or severe hypoxic–ischaemic fetal insult.

However, avoiding hypothermia precludes an open

distal aortic repair, which is preferable.

Progesterone per vaginum and continuous fetal

heart monitoring may reduce the risk to the fetus.After 30 weeks of gestation, caesarean section

followed directly by cardiac surgery seems to be

the most promising option to save the lives of the

mother and her unborn child. Cardiac surgery

should be performed in a hospital in which

neonatal intensive care facilities are available.

Delivery

The primary aim of intrapartum management in

patients with aortic root enlargement is to reduce

the cardiovascular stress of labour and delivery. If

the aortic root diameter is<4.5 cm normal

delivery can be performed, but preferably with

expedited second stage.

Delivery by caesarean section is recommended when the diameter exceeds 4.5 cm. Regional anaesthesia is advised to prevent blood pressure peaks, which may induce dissection. Close monitoring and administration of b-blocking drugs should continue up to 3 months

postpartum, because dissection can occur during

this period.

REGISTRY ON PREGNANCY AND HEART DISEASE

Despite increasing numbers of pregnant womenwith heart disease, management is currently based

on a limited body of adequate research. For up to

date information about treatment during pregnancy

and pregnancy outcome a large prospective

observational registry has been initiated by the

European Society of Cardiology and Association

for European Paediatric Cardiology, which is web

based and now open for inclusion to all cardiologists

and obstetricians taking care of patients with

heart disease (www.euroheartsurvey.org; ehs@

escardio.org).

The categories of fetal risk are:

A: Safe. Controlled studies do not show fetal harm; possibility of harm remoteB: Likely to be safe. No fetal harm shown in animal studies, or harm shown in animal studies but not in controlled human studies.

C: Fetal risk possible, only use if potential benefit outweighs the risk. No data, or fetal harm in animal studies, but no studies in humans.

D: Proven fetal risk, use may be justified if maternal benefit outweighs risk.

X: Proven fetal risk that outweighs any possible maternal benefit.