Women and coronary disease

Heart 2008د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2011

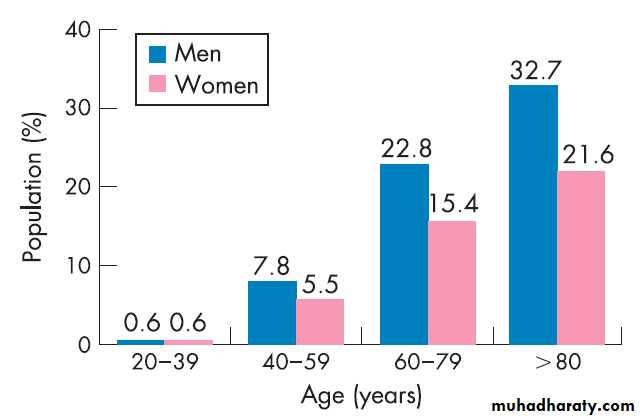

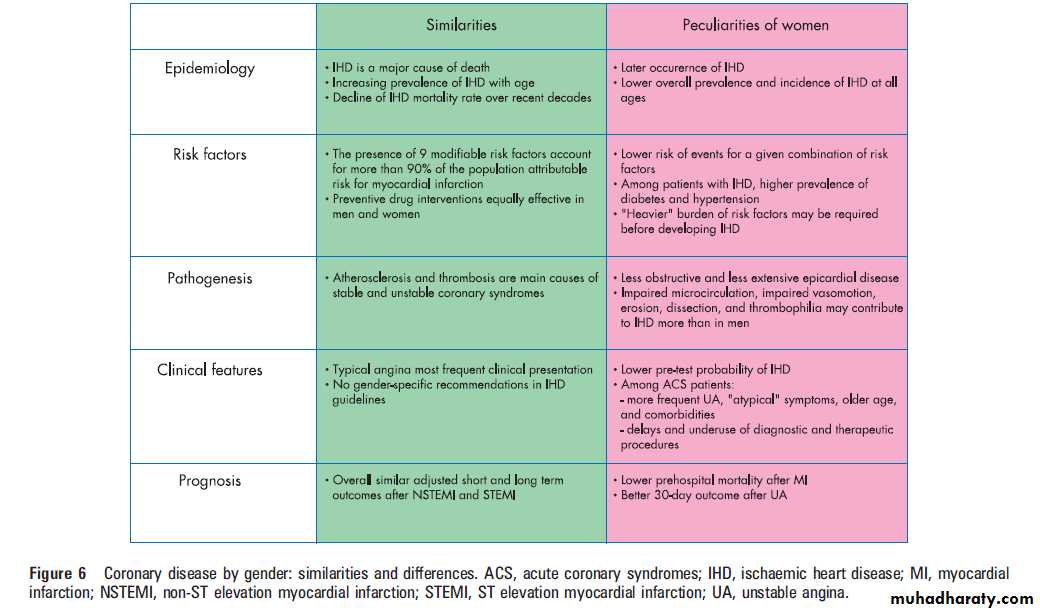

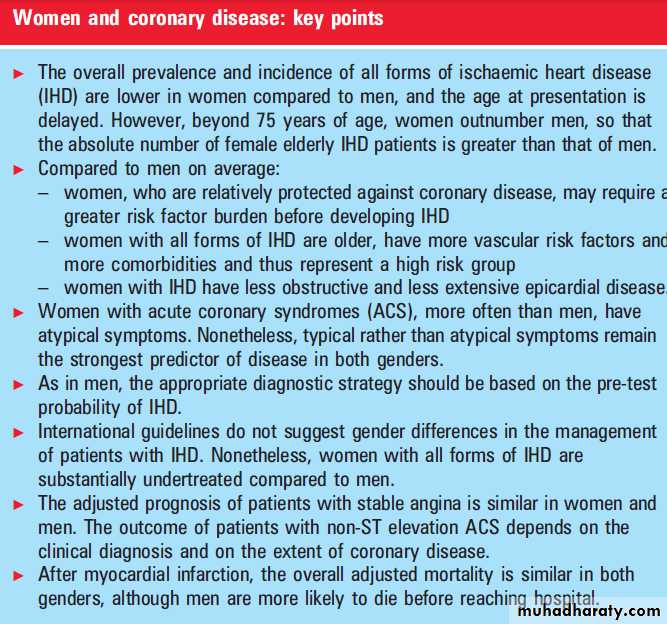

The prevalence and incidence of IHD at all ages

tends to be higher in males than in females,increasing with age in both genders. However, since the female elderly population is larger than that of males, beyond 75 years of age the absolute number of women discharged for IHD overcomes the number of males (364 000 vs 326 000 per year in the USA).

At the time of afirst coronary event, women are approximately 10 years older than men.

In the Framingham Heart Study (FHS), angina was the initial diagnosis of IHD in 61% of women but only in 38% of men; in contrast, men more often exhibit myocardial infarction (MI) or sudden death as first manifestations.Among patients with suspected acute

coronary syndrome (ACS), the discharge diagnosis

in women is more commonly unstable angina

compared to men. Over the past three decades,

the relative risk (RR) of coronary death has

declined similarly in both genders.

CARDIOVASCULAR RISK FACTORS

In the case–control INTERHEART study of 15152patients with MI and 14820 controls, 90% of the

population attributable risk for MI in both genders

was accounted for by the presence of

Nine modifiable risk factors:

raised serum lipoprotein apoB/A1 ratio, smoking, diabetes, psychosocial

stress, hypertension, high waist-to-hip ratio, low

fruit and vegetable intake, lack of regular exercise,

and lack of regular alcohol intake .

Diabetes and hypertension

The prevalence of hypertension in the general population >60 years of age is reported to be higher among women compared to age matched men, although a possible survival bias cannot be excluded.In women, diabetes and hypertension appear to

confer a higher risk of coronary events compared to

men. A possible explanation is that diabetes and

hypertension promote IHD more aggressively in

women than in men, perhaps in relation to the

smaller coronary size.

Alternatively or additionally,we propose that women—who per se are relatively

protected against IHD—may require a greater risk

factor burden compared to men before developing

IHD. Consistent with the latter is the lower

likelihood of disease in women than in men for a

similar combination of risk factors.

A meta-analysis of studies specifically enrolling

diabetic and control subjects, with an averagefollow up of 14 years, found no significant gender

related difference in the risk of coronary death (2.9

for diabetic vs non-diabetic women compared to

2.3 for diabetic vs non-diabetic men, p=0.19) or

non-fatal MI related to diabetes (1.7 for diabetic vs

non-diabetic women compared to 1.6 for diabetic

vs non-diabetic men, p=0.68).

Population based studies, instead, found that women who develop afirst coronary event have a two- to threefold adjusted risk of having diabetes compared to men. Overall, these findings suggest that diabetes and hypertension per se may not increase the risk of

IHD more in women than in men,6 but simply that

women who develop IHD are more frequently

diabetic and hypertensive compared to men

(‘‘higher risk factor burden’’ hypothesis).

Lipids and metabolic syndrome

Beyond 65 years of age, the prevalence of hypercholesterolaemia

(>240 mg/dl, >6.2 mmol/l) is more than twofold greater in women compared to men; as for hypertension.

The odds ratio and population attributable risk for MI associated with a raised lipoprotein apoB/apoA1 ratio are similar in the two sexes.

Low density lipoprotein

(LDL) cholesterol lowering by statins is associatedwith similar reductions in coronary and cerebral

ischaemic events and in overall mortality in men

and women. Whether the presence of metabolic

syndrome confers a higher risk of IHD in women

than in men is not clear. The INTERHEART

study found similar odds ratios for MI associated

with a high waist-to-hip ratio in the two genders.

Smoking and stress

The prevalence of never smokers in the generalpopulation is higher in women than in men (53%

vs 29%). In the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In

Communities) study, current female smokers had a

relative risk of coronary disease of 2.95 vs 1.55 inmen, in line with our hypothesis that women

require a larger cluster of risk factors before

reaching the threshold of IHD.

Perceived high levels of mental stress, compared to low levels, have been associated with an increased risk of fatal IHD in women, but not in men. The

INTERHEART study, on the other hand, found

similar odds ratios for MI in men and women who

smoked or in association with psychosocial stress.

Figure 1 Prevalence of ischaemic heart disease in the USA by age and gender. The prevalence of ischaemic heart disease is lower in women than in men in most classes of age. Reproduced with permission from the Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2007 Update.

Family history

The Physicians’ and Women’s Health Studies (totalling 534 154 subject-years) assigned to amaternal history of MI, especially if premature, ahigher relative risk of cardiovascular disease compared with a paternal history.w13 Given the lower prevalence of MI among females (table 1), amaternal history of MI may signal a more unfavourable background.MECHANISMS OF DISEASE

Women with IHD have less obstructive and less extensive epicardial disease than men, suggesting that other mechanisms—such as impaired microcirculation,impaired vasomotion, erosion, dissection,and thrombophilia—may contribute to ischaemia more frequently than in men.Atherosclerosis

Autopsy data indicate that, in the general population,the severity of coronary stenoses is less in

women than in men, a difference that is lost in the

very elderly. Women admitted to hospital for all

forms of ACS have fewer diseased epicardial

arteries compared to men .

Women with a fatal ACS, compared to men, are

more likely to have plaque erosion, rather than

plaque rupture. Among women, plaque erosion

has been associated with smoking and younger

age. Similarly, spontaneous coronary artery

dissection appears to be more prevalent in women

than in men, particularly if young and without

significant coronary atherosclerosis. Thus, on

average, women have less obstructive and less

extensive epicardial disease than men.

Thrombophilia

In a general Scottish population of 8824 subjects(aged 40–60 years, 4309 women), plasma fibrinogen

values were higher in women than in men for

all age strata. In patients with obstructive

coronary disease, women again showed higher

age adjusted plasma levels of fibrinogen, in addition

to higher plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

antigen and factor VII:C, compared to men.

Interestingly, during the first 24 h after trauma or

injury, young/middle aged women are more

hypercoagulable than men.

Overall, the evidence suggests a greater procoagulant potential in women than in men, a condition which may have conferred survival benefits by limiting postpartum bleeds.

Endothelial/microvascular dysfunction and

vasomotionEndothelial dysfunction can predict adverse coronary

events in men and women, independently of

coronary disease severity, but appears to occur

later in women compared to men. Patients with

angina, normal epicardial arteries and a positive

exercise test (cardiac syndrome X), as well as

Japanese patients with microvascular angina, are

more often women than men. Conversely,

epicardial vasospastic disease (variant angina) does

not show a female predilection.

Oestrogens and menopause

Oestrogens have potential protective cardiovasculareffects through high density lipoprotein (HDL)

and LDL cholesterol modulation, inhibition of

smooth muscle proliferation, enhanced nitric

oxide, prostacyclin and vascular endothelial

growth factor synthesis, and progenitor cell stimulation

; however, they also have potential detrimental

effects (increasing triglycerides and

inflammatory and prothrombotic markers).

Whether the lower prevalence of IHD among premenopausal women compared to age matched

men can be attributed specifically to a protective

role of endogenous oestrogens is still not clear.

Randomised trials testing exogenous oestrogens for

the prevention of IHD showed no benefit or evenharm in terms of cardiovascular events.

To explain these findings, a‘‘timing hypothesis’’ has

been proposed,

whereby oestrogens may be cardioprotective only before the development of advanced atherosclerotic lesions.

Other possible biases may concern the type of oestrogen, concomitant progestins, route of administration, and age and risk factors of enrolled women. Currently,

however, the evidence does not support the use of

oestrogens for the primary or secondary prevention of IHD.

The impact of menopause per se on IHD is

difficult to unravel from the concomitant increasein traditional risk factors.

In the Nurses’ Health Study, each 1 year decrease in age of onset of natural menopause was associated with a small, smoke related, increase in the relative risk of IHD. (RR 1.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01 to 1.05).w29 Bilateral oophorectomy carries an

adjusted relative risk of cardiovascular disease of

4.55 (95% CI 2.56 to 8.01).10 The overall rate of

coronary deaths, however, remains lower in

women than in men up to four decades beyond

the average time of menopause (50–54 years).

Autonomic balance

Women, unlike men, have aprevailing parasympathetic autonomic cardiac tone.

This is consistent with a higher female rate of syncope, hypotension,and bradycardia after MI, and, conversely, with more malignant post-MI tachyarrhythmias and ahigher incidence of sudden cardiac death among men.

PREVENTIVE STRATEGIES

The most important strategy to prevent IHD inwomen is to avoid an underestimation of the risk

of disease.

For primary prevention, in both genders, the use

of aspirin is limited to subjects at high cardiovascular

risk. High risk subjects can be defined as

those with an absolute 10 year probability of a

fatal cardiovascular event >5% when extrapolated

to age 60 years or above, or of MI and coronary

death > 20%.

This risk should be weighed against that of major bleeds with aspirin intake, of approximately 1–2% over 10 years.

Similarly, lipid lowering treatment is currently recommended in both male and female subjects at high cardiovascular risk, who have a total cholesterol > 190 mg/dl (> 5 mmol/l) and/or an LDL cholesterol

> 115 mg/dl (> 3 mmol/l), despite lifestyle changes.

The prevention of IHD events by blood pressure control is of a similar degree in both sexes,

as shown by ALLHAT (Antihypertensive and Lipid

Lowering treatment to prevent Heart Attack Trial)

during 6 years of follow up.

For the secondary prevention of IHD, the

evidence based benefits of several cardiovascular

drugs (aspirin, thienopyridines, statins, inhibitors

of the renin–angiotensin system, b-blockers) are

similar in both genders, despite sex-specific

differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

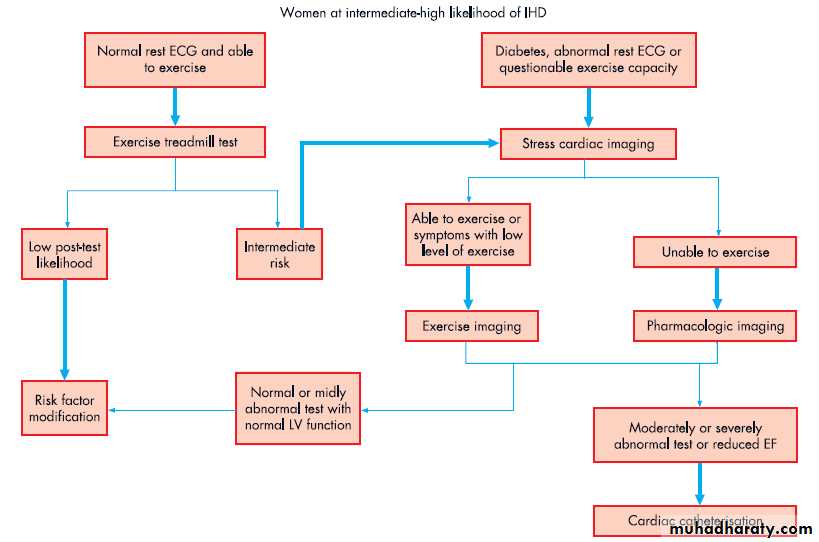

NON-INVASIVE DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

The lower pre-test likelihood of IHD in women

compared to men is associated with a higher

probability of false positive results and thus a

lower specificity of non-invasive diagnostic testing

in women (Bayes’ theorem).

Additionally, the sensitivity of exercise ECG is

lower in women compared to men. The inclusion

of a multiparametric evaluation (for example, the

Duke treadmill score), particularly in women, may

improve the diagnostic accuracy of exercise ECG.

Exercise thallium single photon emission

computed tomography (SPECT) shows a highersensitivity, but not specificity, compared to exercise

ECG in women, although the overall sensitivity

remains lower compared to men.

Technetium-99m sestamibi SPECT yields a higher

specificity compared to thallium SPECT in

women, with similar results in both sexes after

correction for referral bias.

Stress echocardiography

is reported to be the most accurate

provocative test in women (with a higher specificity

and sensitivity compared to SPECT and

exercise ECG) and the most specific test in both

genders.

Coronary calcium score, in both sexes,

may be an important diagnostic tool to rule out

disease, given its high specificity, although its

sensitivity is low.

As in men, the appropriate diagnostic strategy in

women should be based on the pre-test probabilityof IHD. Women with an intermediate–high

pre-test likelihood of IHD should undergo noninvasive

testing .An intermediate–high likelihood of IHD can be defined as women >50 years of age with typical or atypical chest pain, or women ,50 years of age with typical angina, or women with symptoms plus diabetes or other multiple risk factors.

CORONARY ANGIOGRAPHY, PERCUTANEOUS

INTERVENTION AND BYPASS SURGERYWomen undergo cardiac catheterisation less frequently

than men even after MI.

At coronary angiography, women are older and more frequently diabetic and hypertensive. Early studies on balloon angioplasty showed more frequent adverse outcomes and higher dissection rates in women, probably related to comorbidities and smaller coronary size.

In the stent era, several, though not

all, studies show similar adjusted in-hospital

and long term mortality in the two sexes.

Long term rates of other major coronary events and

of restenosis are also similar in both genders.

Vascular complications after percutaneous coronary

intervention (PCI) remain more common in women

than in men.

Current indications for PCI or bypass surgery in the acute and stable patient do not differ according to gender.

Short term mortality is reported to be worse, but long term mortality better, after bypass surgery in women

compared to men.

STABLE ANGINA

Epidemiology and presentationThe CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study) and FHS

reported a lower prevalence and incidence of

angina (defined mostly by physician interview) in

women compared to men .A large Finnish study confirmed a slightly lower, age standardised, annual incidence of angina (assessed by nitrate prescription or by invasive or noninvasive testing) in women, with a male to female ratio of 1.07 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.09). On the contrary, the ARIC study reported a higher

prevalence and incidence of angina, defined by less

restrictive criteria, in women than in men.

In the FHS, angina was the most common first

clinical diagnosis of IHD in women but not in

men. Female patients with angina, compared to

men, are older, more often hypertensive, less

frequently smokers or with prior MI, and report

a higher intensity of pain on a visual analogue

scale. On average, the available data indicate

lower prevalences and incidences of stable angina

in women than in men.

Management and prognosis

In the Euro Heart Survey of 3779 patients withangina, compared to men, women were less likely

to receive non-invasive and invasive diagnostic

procedures, or to be treated by coronary revascularisation and appropriate medical therapy (including the combination of antiplatelet and lipid

lowering drugs), even in the presence of significant

angiographically documented coronary disease.

Several reports indicate a better or similar age

and risk factor adjusted prognosis in women thanin men with diagnosed angina. An important limitation of these studies, however, is the absence of angiography, that isknown to show less extensive coronary disease in women with angina compared to men. In acohort of 1457 patients with stable angina undergoing coronary stenting (32% female), women exhibited similar 1 year relative risk of death,

non-fatal MI and cardiac rehospitalisation compared

to men, even after adjustment for the extent

of coronary disease.

The Euro Heart Survey also found no gender difference in the outcome of the overall population, but assigned an adjusted twofold worse prognosis (death/non-fatal MI at 1 year follow up) to the subgroup of women with

angiographically documented disease compared to

men; this subgroup, however, may have selected

women at particularly high risk. Thus, on

balance, the available data suggest similar outcomes

for men and women with stable angina,

despite a degree of female undertreatment.

ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

Epidemiology and presentation The prevalence and incidence of MI are consistently lower in women than in men, across all classes of age .Among patients withACS, women present more frequently with

unstable angina (UA) and non-ST elevation MI

(NSTEMI) and less frequently with ST elevation

MI (STEMI) compared to men.

Women with ACS report a similar incidence of

chest pain compared to men, but more often an‘‘atypical’’ location (back, jaw, neck), a higher

intensity, and additional nausea, fatigue, dizziness,

dyspnoea, and anxiety/fear.

Thus, symptoms considered ‘‘atypical’’ for men may be ‘‘characteristic’’for women, although not necessarily the most prevalent.

Nonetheless, typical, rather than atypical, symptoms remain the strongest predictor of ACS in both women and men. Women hospitalised for MI are older, and more often hypertensive and diabetic compared to men.

The prevalence of ‘‘normal’’ or non-obstructive

coronary arteries is roughly twofold higher in

women with ACS than in men, particularly for

those with non-ST elevation ACS .

Non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes (UA/

NSTEMI) A recent study showed a significant underuse of medical treatment on admission and even after discharge in women compared to men with non-ST elevation ACS, despite a higher risk factor profile and the lack of gender differences in treatment guidelines.For both genders, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and the European Society of Cardiology UA/NSTEMI guidelines recommend an early invasive strategy (particularly coronary angiography within 48 h) for patients at high cardiovascular risk. The latter may be defined by the presence of recurrent, rest or low threshold ischaemia, dynamic ST segment changes, elevated troponin concentrations, signs of heart failure, malignant arrhythmias, recent PCI, and prior

coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG).

Although not all studies show a significant benefit of

an invasive versus a non-invasive strategy for womenwith non-ST elevation ACS,16 it is important to

consider the lower representation of women than

men in all trials, and the differences across trials in

baseline risk, in timing and type of revascularisation

(CABG vs PCI), and in the use of glycoprotein IIb/

IIIa inhibitors.

The impact of gender on the outcome of non-ST

elevation ACS is debated. Women have a higher

prevalence of non-obstructive coronary disease compared to men, and this subpopulation, in both genders, has a better in-hospital prognosis compared to those with significant disease. At least four studies found male gender independently associated with long term risk of death and even after adjustment for angiographic features, and despite the lesser access of women to invasive and non-invasive diagnostic procedures.

No differences in long term prognosis were found in

other reports on NSTEMI22 or non-ST elevationACS.w67 w75 Finally, one investigation found a worse

prognosis in the subgroup of women with non-ST

elevation ACS and significant coronary stenoses

undergoing PCI compared to men.w64 None of these

studies, however, directly compared patients with

NSTEMI to those with UA.

This comparison was performed within the GUSTO IIb trial that showed a similar adjusted risk of death and reinfarction at 30 days among women and men admitted for NSTEMI, but an independent protective effect of female gender in patients with UA (odds ratio 0.65,95% CI 0.49 to 0.87; p=0.003).

Thus, the available data suggest that the differences in outcome for men and women with UA/NSTEMI largely depend on clinical diagnosis and extent of coronary disease.

Figure 5 A proposed

algorithm for the noninvasiveevaluation of

symptomatic women at

intermediate–high

likelihood of ischaemic

heart disease. See text for

definition of intermediate–

high likelihood. EF, ejection

fraction; LV, left ventricular.

Modified with permission

from Mieres et al.14

ST elevation myocardial infarction

Women with STEMI compared to men are more

likely to present to hospital later, with

atypical symptoms, leading to a more difficult

recognition of MI, a greater delay in obtaining a

first 12 lead ECG, and a more frequent missed

diagnosis.

On average, women have a more frequent history of angina or heart failure and ahigher Killip class.

Even after adjustment for comorbidities and age, women more frequently than men experience in-hospital shock, pulmonary oedema, atrioventricular block, stroke, cardiac rupture, and major bleeds.

In contrast, the incidence of early malignant tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac death are more common in men.

When STEMI is diagnosed, women less often receive appropriate treatment, including admission to

a coronary care unit and thrombolysis.

If rapidly feasible, primary PCI is the better

revascularisation strategy in women as in men,

although vascular complications occur more often in

women. Women experience longer door-to-balloon

delays after diagnosis.

Primary PCI seems to offer better myocardial salvage in women, suggesting greater myocardial tolerance to hypoxia than in men.

Following thrombolysis, several but not all studies report higher adjusted in-hospital and 30 day mortality in women than in men. The apparent discrepancies among these investigations may stem from heterogeneity in statistical adjustments, examined populations, and observed time periods (for example, pre-hospital vs in-hospital).

Indeed, the MONICA study (Monitoring trends and determinants in Cardiovascular disease), that took into account pre-hospital deaths, found a lower prehospital but a higher in-hospital mortality rate in

women compared to men, without significant

gender differences in overall 28 day mortality.

This observation (that men are more likely to die before reaching the hospital) has been confirmed by others. Most studies do not find gender

differences in the adjusted long term mortality

rates after STEMI.

Several but not all studies also report a significant interaction between age and gender related outcome after STEMI, with higher mortality rates after hospitalisation in younger women compared with age matched men, but better outcomes among older women. Again, however, when pre-hospital deaths are taken into account, the higher 30 day mortality in younger (,55 years) hospitalised women, compared to age matched men, disappears, turning into a female advantage.

The adjusted mortality rates after primary PCI in women compared to men are reported to be significantly higher or no different during hospitalisation, but similar at 30 days and long term. Taken together, the above data suggest that overall outcome post-STEMI in the two sexes may not differ substantially, but that early pre-hospital deaths occur more often in men, especially if young.

CONCLUSION

As in men, IHD constitutes a major cause of death and morbidity in women, and this fact is underestimatedby both women and cardiologists.

Educational initiatives specifically tailored to

the female population and to the medical

community will enhance awareness and contribute

to reducing undertreatment of women in the acute setting and in the primary and secondary prevention of disease.

Cardiologists must pay particular attention to women hospitalised for IHD because, on average, they are older, with multiple risk factors and comorbidities, and therefore at high risk. Nonetheless, the lower overall

prevalence of coronary disease in women and its

occurrence at a more advanced age suggest a

protective effect of female gender on the development

of IHD.

In perspective, Elizabeth I (1533–1603) might well have cherished her heart of aqueen when she humbly said, ‘‘I have the body of aweak and feeble woman, but the heart of aking’’