Teaching Topic

د. حسين محمد جمعهاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2012

What medical management strategies for fibroids currently exist?

Surgical and radiologic interventions are currently the mainstay of therapy. The use of oral progestins has not been extensively investigated, but small studies report breakthrough bleeding and possible promotion of myoma growth. The use of a progestin-releasing intrauterine device controls menorrhagia in some patients, but trials have generally excluded patients with uteri distorted by submucosal myomas.Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists are considered to be the most effective medical therapy. In a placebo-controlled trial, the GnRH agonist leuprolide acetate (in a 3.75-mg depot formulation) stopped vaginal bleeding in 85% of patients with anemia before myoma surgery. However, leuprolide acetate suppresses estradiol, and in that trial, 67% of patients reported hot flashes.

Puberty leads to sexual maturation and reproductive capability. It requires an intact hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis and is heralded by the reemergence of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion from its relative quiescence during childhood. GnRH stimulates the secretion of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which then stimulate gonadal maturation and sex-steroid production. Much is known about components of the HPG axis, but the factors that trigger pubertal onset remain elusive. It is not understood why one boy begins puberty at the age of 10 years and another at the age of 14 years.

Delayed Puberty

How is delayed puberty defined?

Delayed puberty is defined as the absence of testicular enlargement in boys or breast development in girls at an age that is 2 to 2.5 SD later than the population mean (traditionally, the age of 14 years in boys and 13 years in girls). However, because of a downward trend in pubertal timing in the United States and other countries and differences in pubertal timing among racial and ethnic groups, some observers have advocated for updated definitions with younger age cutoffs for the general population or perhaps for particular countries or racial or ethnic groups. Development of pubic hair is usually not considered in the definition because pubarche may result from maturation of the adrenal glands (adrenarche), and the onset of pubic hair can be independent of HPG-axis activation.

What is the most common etiology of delayed puberty, and what is the differential diagnosis?

Delayed puberty usually represents an extreme of the normal spectrum of pubertal timing, a developmental pattern referred to as constitutional delay of growth and puberty (CDGP). Although CDGP represents the single most common cause of delayed puberty in both sexes, it can be diagnosed only after underlying conditions have been ruled out.

The differential diagnosis of CDGP can be divided into three main categories: hypergonadotropic hypogonadism (characterized by elevated levels of luteinizing hormone and FSH owing to the lack of negative feedback from the gonads), permanent hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (characterized by low levels of luteinizing hormone and FSH owing to hypothalamic or pituitary disorders), and transient hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (functional hypogonadotropic hypogonadism), in which pubertal delay is caused by delayed maturation of the HPG axis secondary to an underlying condition. The cause of CDGP is unknown, but it has a strong genetic basis. It has been estimated that 50 to 80% of variation in the timing of puberty in humans is due to genetic factors, and 50 to 75% of patients with CDGP have a family history of delayed puberty.

What is an appropriate initial evaluation in a patient presenting with delayed puberty?

A. The aim of initial evaluation is to rule out underlying disorders causing delayed puberty. A family history, including childhood growth patterns and age at pubertal onset of the parents, should be obtained. Patients and their parents should be questioned about a history or symptoms of chronic disease, with emphasis on specific disorders (e.g., celiac disease, thyroid disease, and anorexia) that may cause temporary delay of puberty (functional hypogonadotropic hypogonadism), as well as medication use, nutritional status, and psychosocial functioning. Delayed cognitive development associated with obesity or dysmorphic features may suggest an underlying genetic syndrome.Bilateral cryptorchidism or a small penis at birth and hyposmia or anosmia may suggest hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. A history of chemotherapy or radiotherapy may indicate primary gonadal failure. Physical exam should focus on previous height and weight measurements as well as Tanner stage. A testicular volume of >3 ml in boys indicates central puberty.

Initial testing should include: serum chemistries, bone-age radiography, basal serum LH, FSH, IGF-1, thyrotropin, free thyroxine, and testosterone (in boys). LH and FSH are generally low in patients with CDGP or hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, whereas such levels are usually elevated in those with gonadal failure. Serum levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) can be helpful in the evaluation of growth hormone deficiency but must be interpreted carefully because levels are often low for chronologic age but within the normal range for bone age. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indicated when there are signs or symptoms to suggest a lesion in the central nervous system.

What are the options for treatment in a patient with CDGP?

A. The options for management of CDGP include expectant observation or therapy with low-dose testosterone (in boys) or estrogen (in girls). If puberty has started, clinically or biochemically, and stature is not a major concern, reassurance with realistic adult height prediction is frequently sufficient. The data suggest that treatment leads to increased growth velocity and sexual maturation and positively affects psychosocial well-being, without significant side effects, rapid advancement of bone age, or reduced adult height.Although the Food and Drug Administration has approved the use of growth hormone for the treatment of idiopathic short stature and height that is 2.25 SD below average for age, this therapy has at best a modest effect on adult height in adolescents with CDGP, and its use in CDGP is not recommended. In boys with CDGP and short stature, another potential therapeutic approach is aromatase inhibition, but this treatment requires further study before it should be incorporated into routine practice.

Aromatase inhibitors block the conversion of androgens to estrogens; because estrogen is the predominant hormone needed for epiphyseal closure, the use of aromatase inhibitors could prolong linear growth and potentially increase adult height. However, potentially adverse effects, especially impaired development of trabecular bone and vertebral-body deformities, which were observed in boys with idiopathic short stature who were treated with letrozole, must be considered.

Table 3. Medications for the Treatment of Constitutional Delay of Growth and Puberty (CDGP).

What are the American Diabetes Association criteria for diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes mellitus?

The diagnosis of T2DM, as outlined by the American Diabetes Association (ADA), is based on a HbA1c level ≥6.5%, or fasting plasma glucose level ≥126 mg/dl (7.0 mmol/l), or a 2-hour plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/l) during an oral glucose tolerance test. The diagnosis can also be established by classic symptoms of hyperglycemia and a random plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dl. Test results need confirmation using the above criteria, unless the diagnosis is obvious based on symptoms.

What are the goals of glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes?

Long-term follow-up of patients with newly-diagnosed T2DM enrolled in the U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study showed a reduced risk of CVD events 10 years after the end of the trial among those initially randomized to intensive glycemic management, as compared with conventional therapy (average HbA1c of 7.0% versus 7.9%). Results of three trials in older patients with established T2DM and a history of or risk factors for CVD showed no reduction in total mortality or CVD-related mortality (and increased mortality in the ACCORD study) from intensive lowering of glucose to near-normal levels using multiple agents, compared to standard glycemic control.A first step in glycemic management is setting an appropriate glycemic target in each individual patient. Current guidelines specify HbA1c targets of <7.0% or <6.5%. However, the appropriateness of these goals vary with different clinical characteristics and psychosocial factors, including the patient’s capacity for self-management and home support systems. In general, in patients with recently recognized T2DM and few (or no) complications (especially younger patients), a near-normal glycemic target aimed at prevention of complications over the many years of life can be suggested. In contrast, in older individuals with CVD (or multiple CVD risk factors) higher targets are often appropriate.

Q. What are appropriate lifestyle modifications for patients with Type 2 DM?

A. Weight loss and exercise are important nonpharmacologic approaches to improve glycemic control. A balanced diet rich in fiber, whole grains, and legumes, containing <7% saturated fat and reduced trans fats, and limited in calories and high glycemic index foods, is recommended by the ADA. Exercise has an additive effect to caloric restriction on glycemic control. Patients should be encouraged to perform at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise.Q. What are the guidelines for medical treatment in Type 2 DM?

A. Of the potential strategies for glycemic control, lifestyle modification and metformin are preferred and are cost-effective. By stimulating AMP-activated protein kinase, metformin reduces hepatic glucose production. It causes no weight gain or slight weight loss, and rarely causes hypoglycemia. Patients with high chronic baseline HbA1c (~9.0%) are unlikely to achieve adequate glycemic control with metformin alone, and in patients with significant hyperglycemia (>300 to 400 mg/dl; HbA1c >10–12%), initial insulin therapy should be considered.If metformin monotherapy cannot be used, other oral agents such as sulfonylureas (insulin secretagogues), dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors (e.g., sitagliptin, inhibits the degradation of GLP-1 and results in modest elevations of circulating GLP-1 levels; does not cause weight gain), pioglitazone (activates PPAR-γ, which enhances insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissue and reduces hepatic glucose production) or a GLP-1 receptor agonist (e.g., exenetide or liraglutide, injectable agents that are structurally similar to endogenous GLP-1) can be initiated.

Over time, additional medications become necessary for glycemic control. A logical strategy is to consider agents with complementary modes of action. Strong evidence is lacking to support any one particular second agent over another. Perhaps due to reluctance of patients and providers, insulin is generally added much later than medically indicated.

Why did the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) lower the diagnostic threshold for diabetes from a fasting plasma glucose level of 140 mg per deciliter to 126 mg per deciliter in 1997?

Before 1997, the diagnosis of diabetes was defined by the ADA and the WHO as a fasting plasma glucose level of 140 mg per deciliter or more or a 2-hour plasma glucose level of 200 mg per deciliter or more during an oral glucose-tolerance test conducted with a standard loading dose of 75 g. In 1997, with recommendations from the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus, the ADA and the WHO lowered the diagnostic threshold to a fasting plasma glucose level of 126 mg per deciliter — the level at which a unique microvascular complication of diabetes, retinopathy, becomes detectable.

What is the approximate annualized risk of diabetes among patients with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose?

Longitudinal investigations have shown that persons categorized as being “impaired” by virtue of having impaired glucose tolerance (as identified on the basis of a 2-hour plasma glucose level of 140 to 199 mg per deciliter during an oral glucose tolerance test) or impaired fasting glucose (fasting glucose level of 100 to 125 mg per deciliter) have approximately a 5 to 10% annualized risk of diabetes, a risk that is greater by a factor of approximately 5 to 10 than that among persons with normal glucose tolerance or normal fasting glucose.

Q. What are limitations of the use of glycated hemoglobin testing in screening for diabetes?

A. Despite some advantages, the use of glycated hemoglobin testing has its limitations. Depending on the assay, spuriously low values may occur in patients with certain hemoglobinopathies (e.g., sickle cell disease and thalassemia) or who have increased red-cell turnover (e.g., hemolytic anemia and spherocytosis) or stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease, especially if the patient is receiving erythropoietin. In contrast, falsely high glycated hemoglobin levels have been reported in association with iron deficiency and other states of decreased red-cell turnover.

Inconsistencies in the correlations between glycated hemoglobin and other measures of ambient glycemia have also been reported in different ethnic and racial groups, findings that suggest genetic influences on hemoglobin glycation. For example, blacks appear to have slightly higher glycated hemoglobin levels (an absolute increase of 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points) than whites.

Q. According to the authors, what is the utility of “combined screening?”

A. An alternative to traditional screening recommendations which has been proposed by several investigators is to measure both glycated hemoglobin and fasting plasma glucose, either simultaneously or in sequence, a strategy that might be considered for patients at highest risk. According to the authors, given the different yields of these two measures, this approach is likely to capture substantially more patients than the use of either test in isolation. When the results of two tests are available but discordant, a reasonable and cautious approach is to let the abnormal test result (if repeated and confirmed) guide categorization, as recommended by the ADA.Q. What is the pathophysiology of hypercalcemia in ATLL? Adult T-cell leukemia–lymphoma

A. The pathophysiology of hypercalcemia in patients with ATLL has been linked, in part, to increased osteoclast activity. The neoplastic cells express soluble factors linked to osteoclastic differentiation and bone loss, including parathyroid hormone–related protein, the level of which was mildly elevated in this patient. ATLL cells may have surface expression of the receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (known as RANKL) and may secrete the chemokine macrophage inflammatory protein 1α, both of which induce osteoclast differentiation, suggesting that direct interactions between hematopoietic progenitors and malignant T cells in the bone marrow may play a role in this process.Q. What is the treatment for acute ATLL?

A. The traditional treatment for acute ATLL is multiagent cytotoxic chemotherapy, typically with a regimen such as cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP). A Japanese trial showed that another regimen, referred to as VCAP-AMP-VECP (vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone; doxorubicin, ranimustine, and prednisone; and vindesine, etoposide, carboplatin, and prednisone), produced higher rates of complete remission than did CHOP but no significant improvement in overall survival.An alternative frontline approach, the combination of the antiviral agent zidovudine and interferon, has been explored; recent data has suggested that this regimen leads to longer overall survival than do traditional regimens, but the majority of patients did not achieve a complete remission. Since ATLL is a virally driven hematologic malignant condition, it is an ideal target for the therapeutic mechanisms of allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in selected patients.

The risk of thromboembolic complications with the use of hormonal contraception is an important issue scientifically and is relevant for counseling women about contraceptive options. Several studies have assessed the risk of venous thromboembolism associated with the use of newer hormonal contraceptive products, but few studies have examined thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction, and the results of available studies have been conflicting.

How did the risk of arterial thrombosis among previous users of hormonal contraception compare to the risk among women who had never used it?

The risk among previous users was similar to the risk among women who had never used hormonal contraception. The rate ratio for thrombotic stroke among previous users, as compared with women who had never used hormonal contraception, was 1.04 (95% CI, 0.95 to 1.15), and for myocardial infarction, 0.99 (95% CI, 0.86 to 1.13).

In this study, did the relative risk of an arterial thrombotic event in women taking an intermediate-dose estrogen oral contraceptive differ depending on the type of progestin that was prescribed?

The estimated relative risks of thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction among users of combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) that included ethinyl estradiol at a dose of 30 to 40 µg did not differ significantly according to the type of progestin, ranging from 1.40 to 2.20 for stroke and from 1.33 to 2.28 for myocardial infarction. For both end points, the risk estimates were lowest with contraceptive pills that included norgestimate or cyproterone acetate and were highest with those that included norethindrone or desogestrel.

Q. How did low dose estrogen containing OCPs differ from intermediate dose pills with respect to risk of stroke or myocardial infarction?

A. In this study, women who used oral contraceptives with ethinyl estradiol at a dose of 30 to 40 µg had a risk of arterial thrombosis that was 1.3 to 2.3 times as high as the risk among nonusers, and women who used pills with ethinyl estradiol at a dose of 20 µg had a risk that was 0.9 to 1.7 times as high, with only small differences according to progestin type. The absolute risk, however, is still small. The authors estimate that among 10,000 women who use desogestrel with ethinyl estradiol at a dose of 20 µg for 1 year, 2 will have arterial thrombosis and that 6.8 women taking the same product will have venous thrombosis.

Q. How did progestin containing IUDs and implants as well as the patch and vaginal ring compare to oral contraceptives?

A. None of the progestin-only products, including the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD and the subcutaneous implants, significantly increased the risk of thrombotic stroke or myocardial infarction. In contrast, the relative risk of thrombotic stroke was 3.15 (95% CI, 0.79 to 12.6) among women who used contraceptive patches and 2.49 (95% CI, 1.41 to 4.41) among those who used a vaginal ring. Numbers of myocardial infarctions were too low to provide reliable estimates. The authors conclude that until further evidence emerges, one should expect a higher risk of thrombotic stroke with parenteral administration than with oral administration (estrogen combined with progestin).

The Guillain–Barré syndrome, which is characterized by acute areflexic paralysis with albuminocytologic dissociation (i.e., high levels of protein in the cerebrospinal fluid and normal cell counts), was described in 1916. Since poliomyelitis has nearly been eliminated, the Guillain–Barré syndrome is currently the most frequent cause of acute flaccid paralysis worldwide and constitutes one of the serious emergencies in neurology.

Guillain–Barré Syndrome

What infectious agents are most frequently associated with the development of the Guillain–Barré syndrome?

Two thirds of cases are preceded by symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection or diarrhea. The most frequently identified infectious agent associated with subsequent development of the Guillain–Barré syndrome is Campylobacter jejuni, whereas cytomegalovirus has been identified in up to 10%. The incidence of the Guillain–Barré syndrome is estimated to be 0.25 to 0.65 per 1000 cases of C. jejuni infection, and 0.6 to 2.2 per 1000 cases of primary cytomegalovirus infection. Other infectious agents with a well-defined relationship to the Guillain–Barré syndrome are Epstein–Barr virus, varicella–zoster virus, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

What are the typical clinical manifestations of Guillain–Barré syndrome?

The first symptoms of the Guillain–Barré syndrome are numbness, paresthesia, weakness, and pain in the limbs. The main feature is progressive bilateral and relatively symmetric weakness of the limbs, and the weakness progresses over a period of 12 hours to 28 days before a plateau is reached. Patients typically have generalized hyporeflexia or areflexia. A history of upper respiratory infectious symptoms or diarrhea 3 days to 6 weeks before the onset is not uncommon.Q. How is the diagnosis of Guillain–Barré syndrome established?

A. A lumbar puncture is usually performed in patients with suspected Guillain–Barré syndrome, primarily to rule out infectious diseases, such as Lyme disease, or malignant conditions, such as lymphoma. A common misconception holds that there should always be albuminocytologic dissociation (i.e., high protein and few cells). However, albuminocytologic dissociation is present in no more than 50% of patients with the Guillain–Barré syndrome during the first week of illness, although this percentage increases to 75% in the third week. Some patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and the Guillain–Barré syndrome have pleocytosis.

What is the Miller Fisher variant of Guillain–Barré syndrome?

A. The Miller Fisher syndrome, which is characterized by ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, and areflexia, was reported in 1956 as a likely variant of the Guillain–Barré syndrome, because the cerebrospinal fluid of affected patients showed albuminocytologic dissociation. The Miller Fisher syndrome appears to be more common among patients with the Guillain–Barré syndrome who live in eastern Asia than among those who live in other parts of the world, occurring in up to 20% of patients in Taiwan and 25% of patients in Japan. Most patients with both disorders have evidence of infection 1 to 3 weeks before the development of ophthalmoplegia or ataxia. The presence of distal paresthesia is associated with the Miller Fisher syndrome. Recovery from ataxia and recovery from ophthalmoplegia take a median of 1 and 3 months, respectively.What are the typical manifestations of Wernicke’s encephalopathy?

Wernicke’s encephalopathy, which is caused by a deficiency of thiamine (vitamin B1), is described as an encephaloneuropathic syndrome consisting of changes in mental status (confusion, confabulation, short-term memory loss, and psychosis), ocular dysfunction (nystagmus, gaze palsies, and ophthalmoplegia), and gait ataxia. Usually beginning with double vision, dysarthria, ataxia, and paresthesias of the legs, Wernicke’s encephalopathy can rapidly progress to Korsakoff’s syndrome, which is characterized by anterograde and retrograde amnesia, confabulation, meager content in conversation, lack of insight, and apathy.How should thiamine deficiency be treated?

Clinically significant thiamine deficiency is typically treated with at least 200 mg of parenteral thiamine daily for 2 days, with some experts recommending 500 mg three times daily for 2 days, followed by 500 mg once daily for 5 days. On completion of parenteral treatment, the patient should take an oral thiamine supplement daily. Giving patients with thiamine deficiency glucose before administering thiamine can precipitate or worsen Wernicke’s encephalopathy. There should be a low threshold for thiamine administration to prevent heart failure and Wernicke’s encephalopathy in patients at risk for deficiency or in those with symptoms that may be the result of deficiency.Q. What studies are helpful in making a diagnosis of Wernicke’s encephalopathy?

A. In some patients with thiamine deficiency, plasma thiamine levels are normal; thus, measurement of the more sensitive whole-blood thiamine level is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Though generally not required to make the diagnosis, electromyography will often suggest a generalized, length-dependent polyneuropathy with prominent involvement of sensory axons and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain may show enhancement and enlargement of the mammillary bodies.Q. What are the manifestations of copper deficiency?

A. Copper deficiency causes a myeloneuropathy without an encephalopathy, and this condition can be clinically similar to the subacute combined degeneration seen in cobalamin deficiency. Copper deficiency can be treated with oral or intravenous supplementation. Serum levels of copper and zinc should be followed closely when oral replacement of copper is used, especially in patients who are also receiving a supplement for zinc deficiency, because zinc and copper compete for intestinal absorption. Copper deficiency can also lead to anemia, but the anemia is typically microcytic, a result of iron deficiency.Shock-Wave Lithotripsy

Nephrolithiasis is a common condition, with an approximate lifetime prevalence of 13% in men and 7% in women in the United States. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) II (1976 to 1980) and NHANES III (1988 to 1994) demonstrated a 37% increase in prevalence between these two time periods, an increase encompassing all age groups and both sexes.What conditions contribute to calcium nephrolithiasis?

Calcium-based stones (calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, and brushite) comprise approximately 80% of upper urinary tract stones. The pathogenesis of stone formation is complex and involves not only urinary supersaturation with stone-forming salts but also processes localized to microenvironments within the renal papilla. Calcium stone formation is multifactorial and a variety of pathophysiologic abnormalities may contribute to the risk of stone formation, including hypercalciuria, hyperoxaluria, hyperuricosuria, hypocitraturia and low urine pH. Dietary factors have also been implicated in stone formation.

When is an interventional treatment warranted in the setting of renal calculi?

Patients with renal calculi that are not symptomatic, obstructing, or associated with infection may be observed, although initiation of a medical prophylactic program is advisable to prevent stone progression. Renal calculi associated with pain, obstruction, infection, or continued growth should be treated in order to prevent sepsis or loss of renal function. The primary therapeutic options for surgical management of renal calculi are shock-wave lithotripsy, ureteroscopy, and percutaneous nephrolithotomy.Q. For which type of kidney stones is shock-wave lithotripsy the most effective treatment?

A. Shock-wave lithotripsy is generally most effective for stones less than 1.5 to 2.0 cm in diameter. It is generally not recommended for branched, or staghorn, calculi. The outcome for patients with lower-pole renal calculi is generally poorer than for stones in other locations in the kidney, likely due to impaired clearance of fragments from the dependent lower-pole calyces. As such, shock-wave lithotripsy treatment of lower pole stones should be limited to those less than 10 mm in diameter. Less dense stones, those with an attenuation coefficient <900 Hounsfield units on computerized tomography scans, are more likely to be associated with successful treatment with shock-wave lithotripsy than denser stones. Skin-to-stone distance also correlates with shock-wave lithotripsy success; shorter distances, less than 10 cm, are associated with a greater likelihood of success.

Q. What are the contraindications to shock-wave lithotripsy?

A. Contraindications to shock-wave lithotripsy include active urinary tract infection, uncorrected bleeding diathesis or coagulopathy, distal obstruction, and pregnancy. Obesity and orthopedic or spinal deformities may preclude shock-wave lithotripsy due to inability to properly position or image the patient.Basal Insulin and Cardiovascular and Other Outcomes in Dysglycemia

An elevated fasting plasma glucose level is an independent risk factor for adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Basal insulin secretion is required to maintain fasting plasma glucose levels below 5.6 mmol per liter (100 mg per deciliter), and an elevated fasting plasma glucose level indicates that there is insufficient endogenous insulin secretion to overcome underlying insulin resistance.What were the primary outcomes in this study in a population of patients with impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, or type 2 diabetes who were assigned to insulin glargine or standard treatment?

The incidence of both coprimary outcomes (death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke, or a composite of any of these events, a revascularization procedure, or hospitalization for heart failure) did not differ significantly between treatment groups, with hazard ratios of 1.02 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.94 to 1.11; P=0.63) and 1.04 (95% CI, 0.97 to 1.11; P=0.27) for the first and second coprimary outcomes, respectively. There was also no significant difference in mortality (hazard ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.90 to 1.08; P=0.70) or microvascular events (hazard ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.90 to 1.05; P=0.43).

What were the results of this trial with respect to patients who had impaired glucose tolerance?

This intervention reduced incident diabetes in participants with impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance, though it was associated with modest weight gain and more episodes of hypoglycemia. The study demonstrated that near-normal fasting plasma glucose and glycated hemoglobin levels could be achieved and maintained for more than 6 years with a daily injection of basal insulin with or without an oral agent when self-monitored fasting glucose levels were used by high-risk patients to adjust the dose of insulin glargine.

Q. What were findings in this study with respect to secondary outcomes?

A. The analyses showed no significant difference in the incidence of any cancer (hazard ratio, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.88 to 1.13; P=0.97), death from cancer (hazard ratio, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.77 to 1.15; P=0.52), or cancer at specific sites. There was also no significant difference in angina, amputations, cardiovascular or noncardiovascular hospitalizations, motor-vehicle accidents, or fractures.Q. What effect did insulin glargine have on the development of hypoglycemia?

A. The incidence of a first episode of severe hypoglycemia was 1.00 per 100 person-years in the insulin-glargine group and 0.31 per 100 person-years in the standard-care group (P<0.001). One death attributed to hypoglycemia occurred in a participant while taking insulin glargine. The incidence of a first episode of nonsevere symptomatic hypoglycemia that was confirmed by a self-measured glucose level of 54 mg per deciliter or less was 9.83 and 2.68 per 100 person-years in the insulin-glargine and standard-care groups, respectively (P<0.001); the incidence of any (i.e., confirmed or unconfirmed) nonsevere symptomatic hypoglycemia was 16.72 and 5.16 per 100 person-years, respectively. A total of 2689 participants in the insulin-glargine group (43%) and 4693 in the standard-care group (75%) did not have any symptomatic hypoglycemia.How does celiac disease present and how is it diagnosed?

Symptoms of celiac disease may range from fatigue and no gastrointestinal symptoms to profuse diarrhea with metabolic disturbances. Classic gastrointestinal symptoms of celiac disease include those of malabsorption, such as steatorrhea, flatulence, and abdominal discomfort. Dermatologic manifestations include eczema and dermatitis herpetiformis. Serologic testing is important in the diagnosis of celiac disease; the sensitivity and specificity of IgA antibodies to tissue transglutaminase are greater than 94% in the absence of IgA deficiency, which can occur in up to 2% of persons with celiac disease..HLA testing could be considered if clinical suspicion for celiac disease is high despite negative serologic testing. A biopsy specimen of the small bowel is a cornerstone of the diagnosis of celiac disease and typically reveals villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, or a combination of these

What is the means of transmission and usual presentation of Strongyloides infection?

S. stercoralis is endemic in the tropics and subtropics. The life cycle starts in the soil, where rhabditiform larvae develop into infectious filariform larvae that penetrate the skin, enter the systemic circulation, penetrate the alveolar spaces, are coughed up and swallowed, and enter the gastrointestinal tract. Most cases of strongyloidiasis are asymptomatic or cause only mild symptoms. An acute manifestation is duodenitis, which causes abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or a combination of these. Ground itch is a severely pruritic cutaneous manifestation of the disease. Dermal migration of the larvae may result in urticaria and areas of serpiginous erythema, known as larva currens. Pulmonary manifestations include dry cough and asthmalike symptoms.Q. What are the manifestations of Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome?

A. Hyperinfection with S. stercoralis is the accumulation of a large burden of parasites during the autoinfection cycle. Autoinfection typically occurs in immunocompromised patients, where rhabditiform larvae mature into filariform larvae in the gut and penetrate through the wall of the large intestine or the perianal skin into the systemic circulation. Parasites accumulate primarily in the colon. Eosinophilia may be absent. Mortality associated with strongyloides hyperinfection is estimated to exceed 10%. Localization in the colon and association with severe inflammation, ulceration, and burrowing beyond the mucosa are uncommon in uncomplicated infection and suggest autoinfection and hyperinfection. The presence of filariform larvae and rhabditiform larvae in the stool is a clue that autoinfection has occurred, and a high parasite burden suggests hyperinfection.Q. Why is hyperinfection with strongyloides less common in patients infected with HIV than in those infected with HTLV-I?

A. In patients infected with HTLV-I, the Th1 response is enhanced, and the Th2 response is blunted, resulting in impaired ability to defend against helminths. In HIV infection, loss of CD4+ T cells can affect both the Th1 and the Th2 responses, and in some patients a Th2 response may even predominate. As a result, the Th2 response is not as disproportionately blunted in patients with advanced HIV infection as it is in patients with HTLV-I infection.

Elevated PSA

At least 30% of clinically important prostate cancers may be missed during transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy, and the results are not improved if more than 12 cores are taken (so-called “saturation biopsies”).

What is a Gleason score?

The Gleason score is the sum of the two most common histologic grades in a prostate-gland tumor, each of which is rated on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the most cytologically aggressive. It correlates with prognosis. A higher score is more likely to be seen with disease that is not confined to the prostate, and is also correlated with poorer response to treatment of localized disease.What are the criteria for active surveillance in prostate cancer?

The authors report that criteria for active surveillance for prostate cancer include a PSA level less than 10 ng per milliliter. While the decision to carry out active surveillance is one that must be individualized, in general, in addition to having a relatively low PSA, patients with early clinical disease stage and a Gleason score indicating well or moderately differentiated tumor may be considered for active surveillance.Q. What is transperineal template-guided mapping biopsy (TTMB) of the prostate?

A. Traditional transrectal ultrasound-guided needle biopsy of the prostate allows excellent and convenient sampling of the posterior aspect of the prostate gland, where prostate cancers most commonly originate. On occasion, however, the cancer may arise either centrally or anteriorly and may be beyond the reach of a biopsy needle inserted through the rectum. However, the anterior gland can be reached through a perineal approach, a technique that is used to insert radioactive seeds into the prostate gland for the purpose of treatment (brachytherapy).Precision is needed to ensure that the needles are placed correctly. To achieve this, transrectal ultrasonography is used to visualize the needles, and the needles themselves are passed through holes in a template (grid) that is secured against the perineum. The perforations ensure that the needles are inserted in parallel and with a known relationship to one another. The “repurposing” of this brachytherapy technique for prostate biopsy is known as TTMB, or “grid” biopsy, and the template may be used to insert biopsy needles precisely to any location in the prostate gland.

Q. What are the indications for consideration of TTMB?

A. A PSA level higher than expected for the size of the gland should prompt consideration of TTMB for better sampling of the prostate. Biopsies performed with the use of templates are important for carefully selected patients in whom there is an unexplained discordance between PSA readings and findings on examination of biopsy specimens obtained via transrectal approach. One quarter of patients who undergo TTMB after at least one negative specimen obtained by transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy will have positive results on TTMB.Up to half of these patients have cancers with a Gleason score of 7 or higher. In patients with two or more negative specimens from transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsies, the most common finding in specimens obtained by TTMB was cancer in the anterior lobes. The morbidity associated with TTMB is greater than that associated with transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsies; there is a higher incidence of acute urinary obstruction. Overall, the costs associated with TTMB (e.g., the costs of general anesthesia, the operating room, and the processing of a large number of tissue cores) render it far more expensive than transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsies.

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN), also termed mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis, is diagnosed on the basis of a glomerular-injury pattern that is common to a heterogeneous group of diseases. MPGN accounts for approximately 7 to 10% of all cases of biopsy-confirmed glomerulonephritis and ranks as the third or fourth leading cause of end-stage renal disease among the primary glomerulonephritides.

What is the typical presentation of MPGN?

MPGN most commonly presents in childhood but can occur at any age. The clinical presentation and course are extremely variable — from benign and slowly progressive to rapidly progressive. Thus, patients can present with asymptomatic hematuria and proteinuria, the acute nephritic syndrome, the nephrotic syndrome, chronic kidney disease, or even a rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis.

The varied clinical presentation is caused by differences in the pathogenesis of the disorder and in the timing of the diagnostic biopsy relative to the clinical course. The degree of kidney impairment also varies, and hypertension may or may not be present. Patients who present early in the disease process, when the kidney biopsy shows proliferative lesions, are more likely to have a nephritic phenotype.

In contrast, patients with biopsies showing advanced changes that include both repair and sclerosis are more likely to have a nephrotic phenotype. Patients with classic MPGN often have features of both the acute nephritic syndrome and the nephrotic syndrome — termed the nephritic–nephrotic phenotype.

What are the most common causes of immune-complex mediated MPGN?

Chronic viral infections such as hepatitis C and hepatitis B, with or without circulating cryoglobulins, are an important cause of MPGN. Hepatitis C, which was recognized as a common cause of immune-complex–mediated MPGN in the 1990s, is now considered to be the main viral infection causing MPGN. In addition to viral infections, chronic bacterial infections (e.g., endocarditis, shunt nephritis, and abscesses), fungal infections, and parasitic infections are associated with MPGN, particularly in the developing world.Bacteria associated with MPGN include staphylococcus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, streptococci, Propionibacterium acnes, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, brucella, Coxiella burnetii, nocardia, and meningococcus. MPGN occurs in a number of autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus and occasionally Sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and mixed connective-tissue disorders. Deposition of monoclonal immunoglobulins is associated with MPGN. This may occur in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) low-grade B-cell lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and multiple myeloma.

Q. What conditions are associated with MPGN where immune complex or complement deposition is typically absent?

A. A pattern of injury consistent with MPGN is also noted in thrombotic microangiopathies resulting from injury to the endothelial cells. Thus, the healing phase of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura or hemolytic–uremic syndrome, atypical hemolytic–uremic syndrome associated with complement abnormalities, the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathies, nephropathy associated with bone marrow transplantation, radiation nephritis, malignant hypertension, and connective-tissue disorders can all present with an MPGN pattern of injury on biopsy.

In thrombotic microangiopathies, immunoglobulin and complement are typically absent on immunofluorescence, and electron-dense deposits are not present in the mesangium or along the capillary walls on electron microscopy.

Q. What are the therapeutic options for MPGN?

A. The benefit of long-term alternate-day glucocorticoid therapy for idiopathic MPGN in children was suggested by a few uncontrolled studies and one randomized, controlled trial.There has been no systematic evaluation of glucocorticoid therapy for idiopathic MPGN in adults. The lack of randomized, controlled trials and the current understanding that multiple pathogenic processes lead to MPGN make it impossible to give strong treatment recommendations in this patient population. Associated underlying disease states (infection, autoimmune disease, hematologic dyscrasia) should be treated.

A recent study involving patients with MPGN associated with monoclonal immunoglobulin deposits and no overt hematologic cancer showed that patients had a good response to rituximab. Patients with normal kidney function, no active urinary sediment, and non–nephrotic-range proteinuria can be treated conservatively with angiotensin II blockade to control blood pressure and reduce proteinuria, since the long-term outcome is relatively benign in this context. Follow-up is required to detect early deterioration in kidney function.

Diabetic Retinopathy

What is the clinical presentation of diabetic retinopathy?The features of diabetic retinopathy, as detected by ophthalmoscopy, were described in the 19th century. The involved changes begin with microaneurysms and progress into exudative changes (leakage of lipoproteins [hard exudates] and blood [blot hemorrhages]) that lead to macular edema, ischemic changes (infarcts of the nerve-fiber layer [cotton-wool spots]), collateralization (intraretinal microvascular abnormalities) and dilatation of venules (venous beading), and proliferative changes (abnormal vessels on the optic disk and retina, proliferation of fibroblasts, and vitreous hemorrhage).

Persons with mild-to-moderate nonproliferative retinopathy have impaired contrast sensitivity and visual fields that cause difficulty with driving, reading, and managing diabetes, and other activities of daily living. Visual acuity, as determined with the use of Snellen charts, declines when the central macula is affected by edema, ischemia, epiretinal membranes, or retinal detachment.

How does strict metabolic control impact the incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy?

Epidemiologic studies have shown the effects of hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia — and, to a lesser extent, a high body-mass index, a low level of physical activity, and insulin resistance — on the incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy and clinically significant macular edema.

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) showed that intensive metabolic control reduces the incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy. Although the glycated hemoglobin level is the standard clinical index for predicting the development and progression of diabetic retinopathy, this index accounted for only 11% of the risk of retinopathy in the DCCT.

Similarly, the values for glycated hemoglobin, blood pressure, and total serum cholesterol accounted for only 9 to 10% of the risk of retinopathy in the Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy and other complications develop after 30 years in up to 20% of persons with diabetes who have been treated with intensive metabolic control, and ideal metabolic control is difficult to achieve.

Q. What medical interventions have been shown to be helpful in preventing diabetic retinopathy?

A. Large, randomized trials have revealed that metabolic control, the renin–angiotensin system, peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor α (PPAR-α), and VEGF contribute to human pathophysiology. Notably, renin–angiotensin system inhibitors reduce the incidence and risk of progression of diabetic retinopathy in persons with type 1 diabetes and are now standard therapy.

The PPAR-α agonist, fenofibrate, reduces the risk of progression by up to 40% among patients with nonproliferative retinopathy, as shown in the Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) and the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) studies. The ACCORD study did not show an effect of intensive blood-pressure control on retinopathy progression but did show the benefit of intensive glycemic control in preventing the progression of retinopathy.

Q. What eye-specific treatments are beneficial in patients with diabetic retinopathy?

A. Eye-specific treatments are beneficial in patients whose vision is threatened by macular edema. Use of the VEGF-neutralizing antibodies bevacizumab and ranibizumab improves visual acuity by an average of one to two lines on a Snellen chart, with an improvement of three or more lines in 25 to 30% of patients, and loss of visual acuity decreased by one third.

These improvements, which are seen over a period of 2 years after approximately 10 intraocular injections, are significantly better than the results of laser treatment alone. The VEGF aptamer, pegaptanib, improves visual acuity by approximately one line. Sustained intravitreal delivery of fluocinolone yields a similar likelihood of gaining three or more lines of acuity but with a 60% increase in the risk of glaucoma and a 33% increase in the need for cataract surgery.

The same implant technology delivering a lower dose of fluocinolone did not increase the risk of cataract or glaucoma. Glucocorticoids such as fluocinolone reduce retinal inflammation and may restore the integrity of the blood–retinal barrier by increasing tight-junction protein expression.

Vesicoureteral Reflux

Primary vesicoureteral reflux is the most common urologic abnormality in children. The overall prevalence of the disorder is typically estimated to be about 1%. However, it has been suggested that the actual prevalence may be substantially higher. The frequency with which it is detected depends on the indication for testing that leads to the diagnosis.Endoscopic Treatment of Primary Vesicoureteral Reflux

For example, vesicoureteral reflux is diagnosed in about one third of children (mostly girls) who are evaluated after urinary tract infection and in about 10% of infants (mostly boys) with antenatal hydronephrosis. Vesicoureteral reflux is much less common in black children as compared to white children.

What is the natural course of vesicoureteral reflux?

The natural course of the disorder is spontaneous resolution, which has been reported to occur in anywhere from 25 to 80% of patients. Resolution may be delayed by voiding dysfunction (the inability to release urine with a coordinated bladder contraction and sphincter relaxation), which increases the risk of recurrent urinary tract infection.What are the complications of vesicoureteral reflux?

Vesicoureteral reflux in a child with urinary tract infection may predispose that child to pyelonephritis and renal scarring, termed reflux nephropathy. The renal scarring may be congenital or acquired in origin. The former appears to be a result of segmental renal dysplasia and is seen mostly in boys with high-grade vesicoureteral reflux with no history of urinary tract infection. The latter is a result of renal injury caused by acute pyelonephritis and is seen mostly in girls. Patients with reflux nephropathy may be completely asymptomatic. The known complications of reflux nephropathy include hypertension and proteinuria. In addition, pregnancy-related complications and chronic kidney disease with end-stage renal failure may occur in some patients.Q. What is the standard diagnostic test for vesicoureteral reflux?

A. The standard diagnostic test for vesicoureteral reflux is voiding cystourethrography. This study is typically performed by filling the bladder with a radiocontrast agent through a urethral catheter and then using fluoroscopy to observe the distribution of the dye. Retrograde filling of the upper urinary tract is diagnostic of vesicoureteral reflux, which is graded from I to V, with grade V being the most severe.Q. What is the optimal management of vesicoureteral reflux?

A. The optimal management of vesicoureteral reflux remains a subject of debate. Although it is clear that surgical intervention can eliminate or reduce the severity of reflux itself, the clinical trials do not provide convincing evidence that either surgery or antibiotic prophylaxis can reduce the incidence of recurrent urinary tract infection or, more important, the incidence of renal damage, as compared with surveillance alone. In addition, it is important to recognize that vesicoureteral reflux has a tendency to resolve in many patients with conservative management..

The authors of this review recommend consideration of surgical treatment for patients with higher-grade reflux (grade III, IV, or V), for those in whom antimicrobial prophylaxis has proved to be ineffective (as shown by recurrent urinary tract infections while receiving such therapy), for those who cannot or do not consistently use antimicrobial therapy, and for those with progressive renal scarring. They also recommend consideration of surgical repair in girls with vesicoureteral reflux that persists as puberty approaches given risk of pregnancy-related complications. Voiding dysfunction is a relative contraindication to surgical correction of reflux because the likelihood of treatment failure and recurrent urinary tract infection is substantially increased

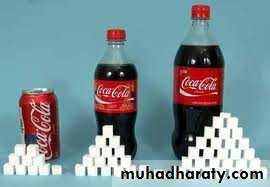

Don't drink your calories

Health tipMedical Progress: Alopecia Areata

The impact of certain skin diseases on the lives of those affected tends to be underestimated or even dismissed as simply a “cosmetic problem.” Alopecia areata exemplifies such a condition, owing to its substantial disease burden and its often devastating effects on the patient’s quality of life and self-esteem.What is the epidemiology of alopecia areata?

Alopecia areata is the most frequent cause of inflammation-induced hair loss, affecting an estimated 4.5 million people in the United States. Depending on ethnic background and area of the world, the prevalence of alopecia areata is 0.1 to 0.2%, with a calculated lifetime risk of 2%. Alopecia areata affects both children and adults and hair of all colors. Although the disorder is uncommon in children under 3 years of age, most patients are relatively young: up to 66% are younger than 30 years of age, and only 20% are older than 40 years of age. There is generally no sex predilection, but more men were found to be affected in one study involving patients who were 21 to 30 years of age.What is the association between alopecia areata and autoimmune disease?

Alopecia areata is associated with an increased overall risk of other autoimmune disorders (16%). For example, it is accompanied by lupus erythematosus in 0.6% of patients, vitiligo in 4%, and autoimmune thyroid disease in 8 to 28%.Q. What is the clinical presentation of alopecia areata?

A. Alopecia areata manifests as the loss of hair in well-circumscribed patches of normal-appearing skin, most commonly on the scalp and in the region of the beard. The onset is typically rapid, and the disease can progress to the point that all scalp hair is lost (alopecia areata totalis) or even that all body hair is lost (alopecia areata universalis). Variants of this disorder include ophiasis, in which hair loss affects the occipital scalp; diffuse forms of alopecia; and demasking, which results in the loss of pigment and sudden “graying.”

These presentations, together with telltale clinical signs, such as exclamation-mark hairs, cadaver hairs, nail pitting, and the growth of white hair in formerly alopecic lesions, often render the diagnosis straightforward.

Q. What treatment options exist for alopecia areata?

A. Curative therapy does not exist. Some clinicians rely on the high rate of spontaneous remission and recommend a wig if remission does not occur. Clinicians have two principal management options — use of an immunosuppressive regimen (preferable for patients with acute and rapidly progressing alopecia areata) or an immune-deviation strategy that manipulates the intracutaneous inflammatory milieu (favored for patients with the chronic, relapsing form).The best-tested immunosuppressive treatment consists of intradermal injections of triamcinolone acetonide (5 to 10 mg per milliliter) given every 2 to 6 weeks. This agent stimulates localized regrowth in 60 to 67% of cases. High-potency topical glucocorticoids with occlusive dressings lead to improvement in more than 25% of affected patients. The most effective form of immunotherapy is topical sensitization with diphenylcyclopropenone or squaric acid dibutylester. Diphencyprone can now be considered first-line therapy for alopecia areata totalis.

HER2-Positive Breast Cancer

HER2, a proto-oncogene encoding the HER2 tyrosine kinase receptor, is amplified in 15 to 20% of patients with breast cancer, resulting in HER2-receptor overexpression and an aggressive clinical phenotype associated with high metastatic potential and shortened survival.What is the current recommendation for treatment in a patient with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer?

The outcome of patients with HER2-positive breast cancer has markedly improved with the advent of molecular targeting of the HER2 receptor with the humanized monoclonal antibody trastuzumab (Herceptin, Genentech). In patients with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer, although single-agent trastuzumab is clinically active, the highest clinical benefit is observed when trastuzumab is given in combination with chemotherapy. Multiple agents in combination with trastuzumab have shown clinical activity. However, the only randomized trials that have shown improved survival are those involving the use of taxanes.

Is there any role for surgical resection of the primary tumor in a patient with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer?

Although surgical resection of the primary tumor has traditionally been reserved for symptom palliation, retrospective series suggest a survival benefit associated with removal of the primary tumor in metastatic disease, and a case-matched series suggests clinical benefit from local therapy in carefully selected patients with metastatic disease.

Q. What is the prognosis in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer?

A. Although an overall response of HER2-positive metastatic disease to first-line therapy occurs in up to 70% of patients, complete remissions are seen in only 7 to 8% of patients. Nonetheless, the remissions can be long-lasting; some patients who participated in the initial clinical trials with trastuzumab are still in remission more than 15 years later.Median survival is shorter in patients who have visceral metastases than in those who have bone-only metastases. Although the disease may recur in multiple sites, trastuzumab-treated populations have an especially high risk of central nervous system metastasis — more than 30% of the patients in some series. The high rate of metastatic disease to the brain is probably due to the high invasive and metastatic potential of HER2-positive breast cancer, together with the limited penetration of trastuzumab across the blood–brain barrier.

Q. How does trastuzumab enhance the cardiotoxic effects of anthracyclines?

A. The heart depends on HER2 signaling to recover from a number of insults, including the cardiotoxic effects induced by anthracyclines. Therapy with trastuzumab prevents HER2 from signaling appropriately in the heart and may be responsible for the enhanced cardiac toxic effects observed when anthracyclines are given in combination with trastuzumab.Urinary tract infection is the most common bacterial infection encountered in the ambulatory care setting in the United States, accounting for 8.6 million visits in 2007. The self-reported annual incidence of urinary tract infection in women is 12%, and by the age of 32 years, half of all women report having had at least one urinary tract infection.

What are the risk factors for uncomplicated sporadic and recurrent cystitis and pyelonephritis?

Risk factors for uncomplicated sporadic and recurrent cases of cystitis and pyelonephritis include sexual intercourse, use of spermicides, previous urinary tract infection, a new sex partner (within the past year), and a history of urinary tract infection in a first-degree female relative. Case–control studies have shown no significant associations between recurrent urinary tract infection and precoital or postcoital voiding patterns, daily beverage consumption, frequency of urination, delayed voiding habits, wiping patterns, tampon use, douching, use of hot tubs, type of underwear, or body-mass index.

Which organisms cause the majority of uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women?

In women, E. coli causes 75 to 95% of episodes of uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis; the remaining cases are caused by other Enterobacteriaceae, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, and gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus). However, the latter two organisms, when isolated from voided urine from women with uncomplicated cystitis, often represent contamination of the voided specimenQ. What are the classic symptoms of cystitis versus pyelonephritis and how does one approach the diagnosis?

A. Cystitis is usually manifested as dysuria with or without frequency, urgency, suprapubic pain, or hematuria. Clinical manifestations suggestive of pyelonephritis include fever (temperature >38°C), chills, flank pain, costovertebral-angle tenderness, and nausea or vomiting, with or without symptoms of cystitis. Dysuria is also common with urethritis or vaginitis, but cystitis is more likely when symptoms include frequency, urgency, or hematuria; when the onset of symptoms is sudden or severe; and when vaginal irritation and discharge are not present.

The only finding on physical examination that increases the probability of urinary tract infection is costovertebral-angle tenderness (indicating pyelonephritis). Results of a dipstick test for leukocyte esterase or nitrites provide little useful information when the history is strongly suggestive of urinary tract infection, since even negative results for both tests do not reliably rule out the infection in such cases. A urine culture is indicated in all women with suspected pyelonephritis but is not necessary for the diagnosis of cystitis. Studies have shown that the traditional criterion for a positive culture of voided urine (105 colony-forming units [CFUs] per milliliter) is insensitive for bladder infection, and 30 to 50% of women with cystitis have colony counts of 102 to 104 CFUs per milliliter in voided urine.

Q. How should episodes of recurrent cystitis be treated?

A. Episodes of cystitis that occur at least 1 month after successful treatment of a urinary tract infection should be treated with a first-line short-course regimen. If the recurrence is within 6 months, one should consider a first-line drug other than the one that was used originally, especially if trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole was used, because of the increased likelihood of resistance.The authors’ recommendations for first-line therapy include nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, fosfomycin, and pivmecillinam. Urinary symptoms that persist or recur within a week or two of treatment for uncomplicated cystitis suggest infection with an antimicrobial-resistant strain or, rarely, relapse. In such women, a urine culture should be performed, and treatment initiated with a broader-spectrum antimicrobial agent, such as a fluoroquinolone.

Brucellosis is widespread in the Middle East. Serologic surveys have shown that 2 to 15% of camels in this geographic area have antibodies against brucella. A recent report describes brucellosis in two persons returning home to Singapore after drinking unpasteurized camel’s milk during the Hajj pilgrimage. In animals in the Middle East, Brucella melitensis (serovar 2 or 3) predominates; in humans, serovar 3 is the cause of most cases.

What is the typical presentation of brucellosis?

Fever is the primary symptom of brucellosis, often with chills; osteoarticular disease is the most common complication when focal infection is diagnosed. One third of patients with brucellosis have hepatic or splenic enlargement, and 10% have genitourinary involvement. Brucellosis often involves the spine; in children, the sacroiliac joint is most frequently involved; in older patients spinal infection is most frequent, and 60% of cases are lumbar, most often at the L4 or L5 level.How do you distinguish a spinal infection secondary to tuberculosis from one involving brucella?

According to the authors, it has been suggested that the constellation of back pain, elevations in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and the level of serum C-reactive protein, a history of previous tuberculosis, and involvement of posterior spinal elements on imaging is pathognomonic of tuberculosis. Marked destruction of vertebral bodies, usually in the thoracic or thoracolumbar area, is more common in tuberculosis, whereas disk destruction is seen more often in brucellosis. Paravertebral abscesses are less common in brucellosis than in tuberculosis, but they can occur. On MRI, a well-defined abnormal paraspinal signal and a thin, smooth abscess wall suggest tuberculous infection.

Q. How is brucellosis diagnosed?

A. The incubation period for brucellosis ranges from 1 to 2 weeks for acute disease to months for late disease. Diagnosis of brucellosis can prove difficult. In automated blood-culture systems, growth often can be detected after 3 to 5 days of incubation. Laboratory personnel should be alerted to the need to hold the cultures longer than the customary 5 days and also to take precautions to avoid infection themselves. If cultures are negative, a presumptive diagnosis can be made serologically, although seropositivity can derive from previous infection and not necessarily indicate active infection, especially in people who have resided in endemic regions.Q. What is the appropriate treatment for brucella infection?

A. Initial treatment typically includes doxycycline for six weeks and IM streptomycin for the first 14 to 21 days, or six weeks of doxycycline and rifampin.Eltrombopag in Cirrhosis

Thrombocytopenia is frequently observed in patients with chronic liver disease, with studies suggesting that it occurs in up to 76% of patients with cirrhosis. The degree of thrombocytopenia is proportional to the severity of the liver disease, and a high degree of thrombocytopenia is an indicator of advanced disease.What are the limitations of platelet transfusions in patients with severe liver disease?

Platelet transfusions are commonly used to reduce the risk of bleeding during a procedure, but their short duration of efficacy and the risk of transfusion reactions limit their use. Furthermore, the development of antiplatelet antibodies (alloimmunization) can cause refractory thrombocytopenia in up to half of patients who receive multiple transfusions.What is the mechanism of action of eltrombopag?

Eltrombopag is an oral thrombopoietin-receptor agonist approved for use in patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia

Q. What were the results of this study, which looked at eltrombopag versus placebo in patients with chronic liver disease and thrombocytopenia?

A. Treatment with eltrombopag at a dose of 75 mg once daily for 14 days reduced the need for platelet transfusions in patients with chronic liver disease and thrombocytopenia who were undergoing elective invasive procedures. Platelet counts were increased during treatment with eltrombopag and for up to 2 weeks after treatment. The key secondary end point of noninferiority with regard to the rate of bleeding episodes (with a noninferiority margin of 10 percentage points) was met (23% in the placebo group and 17% in the eltrombopag group; absolute difference, –6 percentage points; 95% CI, –15 to 3).

Q. How did serious adverse events differ in the two study groups?

A. An increased risk of portal-vein thrombosis was observed among patients receiving eltrombopag. Thrombotic events occurred in 6 patients (7 events) in the eltrombopag group and 2 patients (3 events) in the placebo group (odds ratio with eltrombopag, 3.04; 95% CI, 0.62 to 14.82). With the exception of thrombotic events, rates of serious adverse events were similar in the study groups.Nine of the 10 events involved the portal venous system, including all the events in patients who received eltrombopag; these patients presented with symptomatic portal-vein or splanchnic-vein thromboses. Of the 6 patients in the eltrombopag group who had a portal-vein thrombosis, 5 had the event when the platelet count was higher than 200,000 per cubic millimeter.

Thyroid Cancer

In patients with low-risk thyroid cancer, it is unclear whether the administration of radioiodine provides any benefit after a complete surgical resection, and radioiodine is not recommended in patients with disease that is categorized as consisting of a tumor less than 1 cm in diameter and clinical stage N0. Therefore, radioiodine should be used with great care in order to minimize harm and administer the minimal amount of radioactivity.Why is radioiodine administered to patients with thyroid cancer after total thyroidectomy?

Radioiodine (131I) is administered to patients with thyroid cancer after total thyroidectomy for three reasons: first, to eradicate normal-thyroid remnants (ablation) to obtain an undetectable serum thyroglobulin level; second, to irradiate any neoplastic focus to decrease the risk of recurrence; and third, to perform a 131I total-body scan to detect persistent carcinoma. Successful ablation is defined by the combination of undetectable serum thyroglobulin levels after thyrotropin stimulation and normal results on neck ultrasonography 6 to 12 months after 131I administration.What are the two methods used for thyrotropin stimulation prior to the administration of radioactive iodine for ablation?

The two methods used for thyrotropin stimulation are the use of recombinant human thyrotropin and thyroid hormone withdrawal. Each is administered after surgery and before radioiodine administration. The method used is a matter of debate.

The use of recombinant human thyrotropin maintains quality of life, is cost-effective, and reduces the radiation dose delivered to the body as compared with the amount delivered with thyroid-hormone withdrawal. Recombinant human thyrotropin and thyroid-hormone withdrawal provide similar ablation rates when a radiation activity of 3.7 GBq is administered. Furthermore, whether the 3.7-GBq dose is necessary has been questioned.

Q. What were the primary results of this study, which compared different doses of postoperative radioactive iodine in patients with low-risk thyroid cancer?

A. The primary outcome of this study was thyroid ablation. Ablation was assessed at a mean (±SD) of 8±2 months after radioiodine administration with the use of neck ultrasonography and determination of the level of recombinant human thyrotropin-stimulated serum thyroglobulin or a diagnostic 131I total-body scan in patients with detectable antithyroglobulin antibody.

For the 684 patients who could be evaluated in this study, a follow-up study was performed between 6 and 10 months (average, 8.3±1.6 months) after 131I administration, and no significant difference was found between the 1.1-GBq group and the 3.7-GBq group.

Q. What were the findings in this study with respect to use of thyroid hormone withdrawal versus recombinant human thyrotropin prior to radioactive iodine?

A. The proportion of patients with symptoms of hypothyroidism was significantly higher in the groups undergoing thyroid-hormone withdrawal than in the groups receiving recombinant human thyrotropin. Thyroid-hormone withdrawal was associated with deterioration of the quality of life, as compared with recombinant human thyrotropin. Radioiodine may induce lacrimal and salivary-gland disturbances, depending on the amount of radioactivity administered. The incidence of salivary problems did not differ significantly between groups, but lacrimal dysfunction (runny eyes) was more frequent among patients undergoing thyroid-hormone withdrawal along with low (19%) or with a high (25%) 131I activity than among patients receiving recombinant human thyrotropin (10%).

Whistling in the Dark

It is important to consider a broad differential diagnosis for wheezing, especially when findings are atypical for asthma or when symptoms fail to subside as expected in response to conventional therapy. This case highlights the importance of measuring lung function both when attempting to confirm (or rule out) a diagnosis of asthma if it is suspected and when adjusting medications in patients with established asthma.What is the differential diagnosis of a patient who presents with a cough and wheezing?

Recurrent episodes of shortness of breath, cough, and wheezing suggest a diagnosis of asthma. Nocturnal worsening of symptoms is consistent with this diagnosis. Atypical features, opening the possibility of alternative diagnoses, would be a late age at onset and the absence of identifiable triggers for the symptoms. Other potential causes include recurrent respiratory tract infections, gastroesophageal reflux with microaspiration of gastric contents, and congestive heart failure, including that resulting from valvular heart disease or diastolic dysfunction, which may cause “cardiac asthma.”How does aspirin-associated respiratory disease present?

Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease often presents in adulthood with a characteristic sequence of recurrent sinusitis, followed by the development of asthma and then the recognition of exacerbations of asthma precipitated by ingestion of aspirin or any other cyclooxygenase-1 inhibitor.Q. How does one make the diagnosis of tracheomalacia?

A. The diagnosis of tracheomalacia may be made with the use of fiberoptic bronchoscopy, but the speed of image collection on modern multidetector CT equipment makes chest CT a useful alternative means of diagnosis. Images should be obtained during inspiration and expiration and then compared. For images collected during expiration, the goal is to maximize the abnormal movement of the posterior tracheal wall (or any other malacic portion of the wall).The best time to obtain the image is near but not at the end of exhalation, when the pleural pressure is still positive. Precise criteria for radiographic diagnosis of tracheomalacia have not yet been defined, but many radiologists use a luminal narrowing of 50% on exhalation as a benchmark.

Q. What is the most common cause of tracheomalacia?

A. In adults, the most common cause of tracheomalacia is prolonged mechanical ventilation; high pressures in the endotracheal tube cuff may cause localized ischemic injury to the tracheal wall (the cartilage and the membranous sheath). Other causes of segmental tracheomalacia include prolonged external pressure on the tracheal wall, such as may be caused by a large substernal goiter or a congenital vascular sling (e.g., a right-sided aortic arch with an aberrant subclavian artery). More diffuse tracheomalacia is encountered in patients with the rare conditions of tracheobronchomegaly (Mounier–Kuhn syndrome) and relapsing polychondritis.Limb Ischemia

Acute limb ischemia is defined as a sudden decrease in limb perfusion that threatens the viability of the limb. The incidence of this condition is approximately 1.5 cases per 10,000 persons per year. The clinical presentation is considered to be acute if it occurs within 2 weeks after symptom onset.What are the symptoms and findings on physical examination in acute limb ischemia?

Symptoms develop over a period of hours to days and range from new or worsening intermittent claudication to pain when the patient is at rest, paresthesias, muscle weakness, and paralysis of the affected limb. Physical findings may include an absence of pulses distal to the occlusion, cool and pale or mottled skin, reduced sensation, and decreased strength. These features of acute limb ischemia are often grouped into a mnemonic known as the six Ps: paresthesia, pain, pallor, pulselessness, poikilothermia (impaired regulation of body temperature, with the temperature of the limb usually cool, reflecting the ambient temperature), and paralysis.What is the appropriate initial evaluation of acute limb ischemia?

Acute limb ischemia should be distinguished from critical limb ischemia caused by chronic disorders in which the duration of ischemia exceeds 2 weeks and is usually much longer. A careful examination of the limbs is necessary to detect signs of ischemia, including decreased temperature and pallor or a mottled appearance of the affected limb.Sensation and muscle strength should be assessed. The vascular examination includes palpation of pulses in the femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial arteries in the legs and in the brachial, radial, and ulnar arteries in the arms. The presence of flow, particularly in the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries supplying the affected foot or radial and ulnar arteries of the symptomatic hand, is routinely assessed by means of Doppler imaging.

If flow is audible, perfusion pressure to the ischemic limb can be measured with a sphygmomanometric cuff placed at the ankle or wrist just proximal to the Doppler probe; a perfusion pressure of less than 50 mm Hg indicates limb ischemia. Optimal management requires prompt administration of intravenous heparin to minimize thrombus propagation.

Q. When should endovascular versus surgical intervention be used for treatment?

A. On the basis of several randomized trials and recent case series, catheter-directed thrombolysis has the best results in patients with a viable or marginally threatened limb, recent occlusion (no more than 2 weeks’ duration), thrombosis of a synthetic graft or an occluded stent, and at least one identifiable distal runoff vessel. Surgical revascularization is generally preferred for patients with an immediately threatened limb or with symptoms of occlusion for more than 2 weeks.Q. What is reperfusion injury?

A. Reperfusion may result in injury to the target limb, including profound limb swelling with dramatic increases in compartmental pressures. Symptoms and signs include severe pain, hypoesthesia, and weakness of the affected limb; myoglobinuria and elevation of the creatine kinase level often occur. Since the anterior compartment of the leg is the most susceptible, assessment of peroneal-nerve function (motor function, dorsiflexion of foot; sensory function, dorsum of foot and first web space) should be performed after the revascularization procedure.The diagnosis is made primarily from the clinical findings but can be confirmed if the compartment pressure is more than 30 mm Hg or is within 30 mm Hg of diastolic pressure.

If the compartment syndrome occurs, surgical fasciotomy is indicated to prevent irreversible neurologic and soft-tissue damage.

The Wolf at the Door

• Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and the hemophagocytic syndrome are two important and related causes of fever and pancytopenia.What laboratory abnormalities are commonly seen in SLE?