Liver

د. حسين محمد جمعهاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2011

Chronic Hepatitis C Infection

Infection with HCV affects an estimated 180 million people globally.It is a leading cause of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer and a primary indication for liver transplantation in the Western world.

NEJM june 23, 2011

There are at least six major HCV genotypes

Genotype 1 accounts for the majority of infections in North America, South America, and Europe. The predominant riskfactor for HCV acquisition is injection-drug use; among U.S. adults 20 to 59 years of age with any history of illicit injection-drug use, the prevalence of HCV infection is greater than 45% Other risk factors include blood transfusion before 1992, high

lifetime number of sexual partners, and iatrogenic transmission, including through dialysis; in large series, 15 to 30% of patients report no risk factors.

15 to 30% of patients in whom chronic infection develops have progression to cirrhosis over the ensuing three decades.

Patients with HCV-related cirrhosis warrant surveillance for complications, including hepatocellular carcinoma, which develops in 1 to 3% of such patients per year. For patients with clinically significant hepatic fibrosis (Metavir stage ≥2 or Ishak stage ≥3) ,there is widespread agreement that antiviral therapy is indicated because of the high risk of cirrhosis.

Prospective data indicate that the stage of fibrosis predicts clinical outcomes; the cumulative 6-year incidence of liver transplantation or liver-related death ranges from 4% for an Ishak fibrosis score of 2 to 28% for an Ishak score of 6. Because of the extended interval between infection and the

emergence of complications, the HCV-related disease burden is projected to increase severalfold over the next 20 years.

Diagnosis and Clinical Staging

Liver biopsy remains the standard for assessmentof hepatic fibrosis and is helpful for prognostication

and decision making. The histologic pattern

of HCV infection consists of lymphocyte infiltration

of the parenchyma, lymphoid follicles in portal

areas, and reactive bile-duct changes. However,

liver biopsy is costly and invasive, and it carries a

risk of complications (e.g., 1 to 5% of patients who

undergo the procedure require hospitalization).

Additional limitations of biopsy include sampling

error and interobserver variability.

Several methods have been used to quantify

hepatic fibrosis, including the simple aspartateaminotransferase:platelet ratio index (APRI) and

commercially available assays of some or most

of the following biomarkers:

α2-macroglobulin,

α2-globulin,

γ-globulin,

apolipoprotein A-I,

γ-glutamyltransferase,

total bilirubin, and hyaluronic acid.

Management

Interferon-Based Antiviral Therapy

Substantial progress has been made in the treatment

of HCV infection. The goals of therapy are

to prevent complications and death from HCV infection;regardless of the stage of fibrosis, symptomatic extrahepatic HCV (e.g.,cryoglobulinemia)

is an indication for therapy.

Over the past decade,on the basis of considerable data from randomized trials,

pegylated interferon (peginterferon)

plus ribavirin became the standard of care

for all HCV genotypes.

The two licensed peginterferons (Pegasys,

Roche, and PegIntron, Merck) have been shown inhead-to-head comparison to be equivalent in efficacy and to have similar safety profiles. Among patients with genotype 1 who are treated with peginterferon at the standard weight-based dose of ribavirin (1000 or 1200 mg per day) for 48 weeks, 40 to 50% have a sustained virologic response(defined as an undetectable HCV RNA level

24 weeks after the cessation of antiviral therapy).

A shorter course of treatment and a lower ribavirin dose are associated with lower rates of sustainedm virologic response (and higher relapse rates) among genotype 1–infected patients.

In contrast,

patients with genotype 2 or 3, who accountfor approximately one quarter of HCV-infected

patients in the United States, have rates of sustained virologic response in the range of 70 to

80% after taking peginterferon and ribavirin at

a reduced dose (800 mg per day) for 24 weeks.

A sustained virologic response is associated with permanent cure in the vast majority of patients.

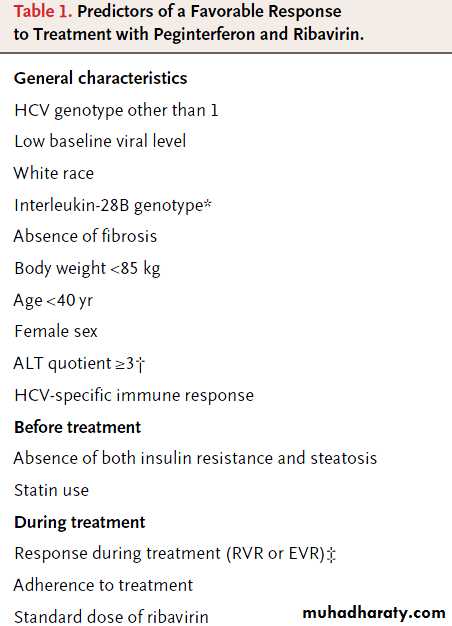

Regardless of the infecting genotype, the likelihood of a sustained virologic response is lower among patients

with a high pretreatment HCV RNA level (with a

high level defined as >600,000 IU per milliliter in

some studies and >800,000 IU per milliliter in

others) and higher among patients with better

adherence to antiviral therapy (receiving 380% of

total interferon and ribavirin doses for 380% of

the expected duration of therapy).

Adherence can be problematic because of the plethora of side effects, including fevers,

influenza-like symptoms,headache,

cytopenias,

fatigue, anorexia,

depression,and anxiety.

On-treatment viral kinetics have emerged as

important predictors of the likelihood of responseand are used to guide the duration of therapy.

An early virologic response is defined as a decrease in the HCV RNA level of at least 2 log10

IU per milliliter or the complete absence of serum

HCV RNA at week 12 of therapy.

The lack of such a response in a patient has a very high negative predictive value for a sustained virologic response.

Among patients with previously untreated genotype 1 infection, more than 97% of those who do not have an early virologic response to treatment will not have a sustained response.

A rapid virologic response, defined as an undetectable HCV RNA level (<50 IU per milliliter) at week 4 of treatment, has been shown to predict a sustained virologic response, as well as to identify those patients for whom the duration of therapy can be shortened without compromising the virologic response.

A rapid virologic response, defined as an undetectable HCV RNA level (<50 IU per milliliter) at week 4 of treatment,

Has been shown to predict

a sustained virologic response, (i.e. the infection was no longer detected in the blood 24 weeks after stopping treatment)as well as to identify those patients

for whom the duration of therapy can be shortened without compromising the virologic response.A recent metaanalysis of seven randomized trials has shown that genotype 1–infected patients with a low baseline HCV RNA level (<400,000 IU per milliliter) who have a rapid virologic response may discontinue therapy at 24 weeks rather than continue for the standard 48 weeks.32 A reduction of the treatment duration has the added benefits of decreased costs and side effects.

Race is another important predictor of response

to antiviral therapy. Black patients havesignificantly lower rates of sustained virologic

response than white patients (28% vs. 52%).

Although the reasons for this difference have

been uncertain, recent data from genomewide

association studies have indicated that singlenucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on chromosome 19 in or near the interleukin-28B gene (IL28B,encoding interferon lambda-3) are highly predictive of successful antiviral treatment.

In an analysis that was adjusted for other predictors, the chance of cure was more than doubled with homozygosity for the C allele at the rs12979860SNP, as compared with the TT genotype (78% for the CC genotype, 38% for the TC genotype, and 26% for the TT genotype). The C allele is much more frequent in white and Asian populations than in black populations.

The nonstructural 3 (NS3) serine protease inhibitors

are the furthest along in development. Inaddition to ablating replication, protease inhibition

blocks the ability of the NS3/4A serine protease

to cleave the HCV polyprotein and interferon-β

promoter stimulator 1, thus restoring innate immune

signaling within hepatocytes (Fig. 3B).15

Two protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir,

were recently approved by the Food and Drug

Administration (FDA).

Two protease inhibitors,

telaprevir andboceprevir

were recently approved by the

(FDA).

In the Protease Inhibition for Viral Evaluation

1 trial ,which involved genotype 1–infected patients who had not previously received treatment, the rates of sustained virologic response were 61% and 69%, respectively, among

those who received a 12-week course of telaprevir,

an orally bioavailable inhibitor of NS3/4A,38 in

combination with peginterferon–ribavirin, which

was continued for an additional 12 weeks (total

duration of antiviral therapy, 24 weeks; T12PR24

As compared with standard therapy with peginterferon–ribavirin, the addition of telaprevir resulted in a shorter median time to achieve an undetectable HCV RNA level (<30 days, vs.113 days). Major side effects of telaprevir included rash, pruritus, anemia, and gastrointestinal

symptoms. The observation that viral relapse

(detectable HCV RNA level during the 24-week

posttreatment period in patients with an end-oftreatment response) occurred in 48% of patients

who did not receive ribavirin (T12P12 in Fig. 4)

underscores the critical role of this agent in preventing

relapse and the emergence of telaprevir

resistance.

The ADVANCE (A New Direction in HCV Care:

A Study of Treatment-Naive Hepatitis C Patientswith Telaprevir) trial (NCT00627926), a phase III

randomized trial reported in this issue of the

Journal, incorporated on-treatment response to

tailor the duration of additional peginterferon–

ribavirin. Telaprevir and peginterferon–ribavirin

were administered for the first 12 weeks or

for 8 weeks, followed by 4 weeks of placebo.

Extended rapid virologic response was defined as

an undetectable HCV RNA level (<25 IU per milliliter) at week 4 and week 12 of therapy; patients who did not have an extended rapid virologic response received 36 additional weeks of

peginterferon–ribavirin, for a total of 48 weeks.

More than half of the telaprevir-treated patients

had an extended rapid virologic response, and

24 weeks of total therapy was associated with

a rate of sustained virologic response that was

higher than 80% among these patients.

As in all the other telaprevir studies, virologic failure was more common in patients with genotype 1a than in those with genotype 1b. The REALIZE (Retreatment of Patients with Telaprevir-based Regimen to Optimize Outcomes) study,

Showed that the addition of telaprevir to peginterferon– ribavirin significantly increased the rate of sustained virologic response among patients who had previously received treatment, particularly in prior relapsers (patients with an undetectable

HCV RNA level at the end of a prior course of

peginterferon–ribavirin therapy but with a detectable

HCV RNA level thereafter).

The Serine Protease Inhibitor Therapy 1 trial

and the SPRINT-2 trialhave shown the efficacy of boceprevir

in combination with peginterferon alfa-2b

and ribavirin in genotype 1–infected patients who had not previously received treatment .

Principal side effects of boceprevir included anemia

(necessitating treatment with erythropoietin

analogues in many patients) and dysgeusia, which

appeared to be more common than previously

reported with telaprevir; rash was reported less

frequently than in the telaprevir trials.

Mathematical modeling has projected that if

the rate of response to antiviral therapy increasesto 80%, which appears to be likely in the foreseeable future, treatment of half of HCV-infected persons would reduce cases of cirrhosis by

15%, cases of hepatocellular carcinoma by 30%,

and deaths due to liver disease by 34% after just

10 years.

Areas of Uncertainty

Transient elastography (FibroScan, Echosens) isa novel noninvasive technique that measures liver stiffness by assessing the velocity of a shear wave created by a transitory vibration. Thresholds for a high likelihood of clinically significant fibrosis

(Metavir score ≥2) have been defined.

The technique has an increased failure rate among obese patients, and it has not been approved by the FDA.

Whether modifications of existing technologies

(e.g., computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging) will provide sensitive differentiation of levels of hepatic fibrosis requires further study.

Although peginterferon–ribavirin is likely to

remain the backbone of antiviral therapy for the foreseeable future, options for treating HCV are

expected to expand rapidly in upcoming years.

The optimal combination of agents (including

nucleoside and nonnucleoside polymerase inhibitors, inhibitors of NS4B and NS5A proteases,

modulators of the immune response, and medications that interfere with lipid metabolism,

which is essential for the assembly and maturation

of HCV particles) and duration of therapy will

need to be defined, in order to maximize rates

of sustained virologic response while minimizing

the risk that resistance will develop.

A recent pilot study of a combination of directly acting antiviral agents suggests the possibility of treating HCV infection with an interferon-free, oral approach. Further study is needed in subgroups of patients with lower response rates, including black patients, patients without a response to prior treatment, liver-transplant recipients, and those who have coinfection with HIV, a high baseline viral load, advanced fibrosis, or insulin resistance.

Guidelines

The American Association for the Study of LiverDiseases and the American Gastroenterological

Association have published guidelines for the

assessment and management of chronic HCV infection, but these guidelines were issued before

the publication of data from randomized trials of

directly acting antiviral agents. Newer European

guidelines take these data into account; the recommendations provided below are generally consistent with these guidelines.

Conclusions and

RecommendationsHCV genotype 1 with a high viral load,should be vaccinated for hepatitis A because of an increased risk of liver failure among patients with chronic hepatitis C infection; hepatitis B vaccination is also indicated in those without evidence of prior exposure. Possible contraindications to treatment

(e.g., depression) should be determined, and the

patient should be informed about potential side effects of antiviral therapy.

Although some clinicians would administer treatment without performing a liver biopsy, I would recommend a biopsy to assess the degree of fibrosis. For a patient with

clinically significant fibrosis (Metavir score ≥2), triple antiviral therapy with peginterferon–ribavirin

and an NS3/4A protease inhibitor, either telapreviror boceprevir, should be recommended.

On the basis of data from recent randomized

trials, a reasonable initial regimen would be telaprevirwith peginterferon–ribavirin for 12 weeks.

If tests for HCV RNA were negative at weeks

4 through 12 (indicating an extended rapid virologic

response), only 12 additional weeks of peginterferon–

ribavirin would be recommended,

whereas if an extended rapid virologic response

were not achieved, peginterferon–ribavirin would

be continued for an additional 36 weeks.

If boceprevir were used, according to new FDA guidelines, a 4-week lead-in phase of peginterferon–ribavirin would be followed by peginterferon–ribavirin and boceprevir for 24 weeks (a totalof 28 weeks) if tests for HCV RNA were negative at weeks 8 through 24 of treatment.

If the tests were positive between weeks 8 and 24 but negative at week 24, peginterferon–ribavirin and boceprevir would be continued for an additional 8 weeks, followed by an additional 12 weeks of peginterferon–ribavirin (a total of 48 weeks).

Alternatively, if the patient has milder fibrosis and is reluctant to receive treatment, it would be reasonable to wait and reevaluate as new therapeutic agents become available.

NEJM june 23, 2011

FDA approves Incivek for hepatitis C

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Incivek (telaprevir) (May 23, 2011) to treat certain adults with chronic hepatitis C infection. Incivek is used for patients who have either not received interferon-based drug therapy for their infection or who have not responded adequately to prior therapies. Incivek is approved for use with interferon therapy made up of peginterferon alfa and ribavirin.

The current standard of care for patients with chronic hepatitis C infection is peginterferon alfa and ribavirin taken for 48 weeks. Less than 50 percent of patients respond to this therapy.

The safety and effectiveness of Incivek was evaluated in three phase 3 clinical trials with about 2,250 adult patients who were previously untreated, or who had received prior therapy. In all studies patients also received the drug with standard of care. In previously untreated patients, 79 percent of those receiving Incivek experienced a sustained virologic response (i.e. the infection was no longer detected in the blood 24 weeks after stopping treatment) compared to standard treatment alone.

The sustained virologic response for patients treated with Incivek across all studies, and across all patient groups, was between 20 and 45 percent higher than current standard of care.

The studies indicate that treatment with Incivek can be shortened from 48 weeks to 24 weeks in most patients. Sixty percent of previously untreated patients achieved an early response and received only 24 weeks of treatment (compared to the standard of care of 48 weeks).

The sustained virologic response for these patients was 90 percent.

When a person achieves a sustained virologic response after completing treatment, this suggests that the hepatitis C infection has been cured. Sustained virologic response can result in decreased cirrhosis and complications of liver disease, decreased rates of liver cancer, and decreased mortality.People can get HCV in a number of ways, including: exposure to blood that is infected with the virus; being born to a mother with HCV; sharing a needle; having sex with an infected person; sharing personal items such as a razor or toothbrush with someone who is infected with the virus, or from unsterilized tattoo or piercing tools.

Incivek is a pill taken three times a day with food. Incivek should be taken for the first 12 weeks in combination with peginterferon alfa and ribavirin. Most people with a good early response to the Incivek combination regimen can be treated for 24 weeks rather than the recommended 48 weeks of treatment with the standard of care. Incivek is part of a class of drugs referred to as protease inhibitors, which work by binding to the virus and preventing it from multiplying.

The most commonly reported side effects in patients receiving Incivek in combination with peginterferon alfa and ribavirin include rash, low red blood cell count (anemia), nausea, fatigue, headache, diarrhea, itching (pruritus), and anal or rectal irritation and pain. Rash can be serious and can require stopping Incivek or all three drugs in the treatment regimen.

On May 13, FDA approved Victrelis (boceprevir), another new treatment for chronic hepatitis C, marketed by Merck of Whitehouse Station, N.J.

Incivek (telaprevir)

Victrelis (boceprevir)

protease inhibitors

• What are the predominant risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection?

• The predominant risk factor for HCV acquisition is injection-drug use; among U.S. adults 20 to 59 years of age with any history of illicit injection-drug use, the prevalence of HCV infection is greater than 45%. Other risk factors include blood transfusion before 1992, high lifetime number of sexual partners, and iatrogenic transmission, including through dialysis; in large series, 15 to 30% of patients report no risk factors.Approximately what percentage of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection have progression to cirrhosis?

Although the natural history of HCV infection is highly variable, an estimated 15 to 30% of patients in whom chronic infection develops have progression to cirrhosis over the ensuing three decades.

A number of factors, including a longer duration of infection, an older age at the time of exposure, male sex, coinfection with other viruses such as HIV, and daily alcohol consumption, but not viral level or genotype, have been consistently associated with an increased risk of fibrosis.

Triple Therapy for Genotype 1 Hepatitis C Infection

A new regimen that included boceprevir yielded high rates of sustained virologic response.Triple therapy with peginterferon, ribavirin, and a specifically targeted antiviral agent such as a protease inhibitor will soon be available to improve sustained virologic response (SVR) in patients infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1. In this industry-funded, open-label, multicenter, phase II trial, researchers assessed the efficacy of 800 mg of boceprevir (thrice daily), an NS3 protease inhibitor, in combination with peginterferon alfa-2b (1.5 µg/kg) and ribavirin (800 to 1400 mg/day).

Published in Journal Watch Gastroenterology August 20, 2010

In all, 520 treatment-naive patients were randomly assigned to one of five regimens:

Peginterferon plus ribavirin for 48 weeks (control group)Peginterferon plus ribavirin for 4 weeks and then both drugs plus boceprevir for 24 weeks

Peginterferon plus ribavirin for 4 weeks and then both drugs plus boceprevir for 44 weeks

Peginterferon, ribavirin, and boceprevir for 28 weeks

Peginterferon, ribavirin, and boceprevir for 48 weeks

Subsequently, 75 patients were randomized to receive triple therapy in which the ribavirin was administered at either the standard dose (800–1400 mg/day) or a lower dose (400–1000 mg/day).

In an intent-to-treat analysis, rates of the primary endpoint — SVR at 24 weeks — were significantly higher in the boceprevir groups (range, 54% with 28-week triple therapy to 75% with 44-week triple therapy preceded by a 4-week lead-in) than in the control group (38%); comparisons with the control group ranged from P=0.013 to P<0.0001.

Among the boceprevir groups, the rate of viral breakthrough (with mutations) was nonsignificantly lower in those who received a two-drug lead-in than in those who did not (4% and 9%; P=0.057). Low-dose ribavirin recipients had a high rate of viral breakthrough with resistance. Compared with the control group, the boceprevir groups had higher rates of anemia (55% vs. 34%) and dysgeusia (27% vs. 9%).

Comment: In this phase II study involving treatment-naive patients with HCV genotype 1 infection, triple therapy with peginterferon, ribavirin, and boceprevir for 44 weeks — preceded by a 4-week lead-in without the boceprevir — achieved an SVR rate of 75%. If a nearly complete phase II trial verifies this striking result, clinicians will soon be able to choose between this and a triple-therapy option involving telaprevir (JW Gastroenterol Apr 29 2009). Both the telaprevir and boceprevir regimens are likely to yield high SVR rates, but boceprevir will be given for 48 weeks in most cases, and telaprevir for 24 weeks. Both drugs will add to the adverse effects: skin rash with telaprevir, anemia with boceprevir.

Published in Journal Watch Gastroenterology August 20, 2010

HCV genotype and virologic response to treatment determine the duration of treatment. Patients with genotypes 1 and 4 are treated for 48 weeks, and those with genotypes 2 and 3 are treated for 24 weeks. Multidrug regimens may be developed in the future, using new agents in combination with current therapies.

Am Fam Physician. 2010

"The quantitative HCV RNA level is used to assess response to therapy and as a guide to discontinue treatment," the review authors write.

"A negative viral load test after four weeks of therapy is predictive of sustained virologic response.

In contrast, failure to achieve a 100-fold reduction in viral load by week 12 of therapy has a strong negative predictive value for sustained virologic response and suggests that treatment is likely ineffective and should be stopped."

Absolute contraindications to treatment of HCV infection include

active alcohol or substance abuse,active autoimmune hepatitis or other condition known to be exacerbated by interferon and ribavirin, known

hypersensitivity to medications used to treat HCV infection, and

pregnancy or lack of compliance with adequate contraception.

For ribavirin only, renal failure is an absolute contraindication.

Other absolute contraindications to treatment of HCV infection are severe concurrent cardiopulmonary disease; uncontrolled major depressive illness, psychosis, or bipolar disorder; and untreated hyperthyroidism.

Relative contraindications to treatment of HCV infection include laboratory values suggesting decompensated cirrhosis, and baseline hematologic and biochemical indices.

Treatment of patients with chronic HCV infection should include counselling them to abstain from alcohol use. Although no vaccine currently exists to prevent HCV infection, persons infected with HCV should be vaccinated against hepatitis A and B. Persons with chronic HCV infection and cirrhosis should periodically undergo ultrasound imaging as surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma, according to recommendations from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Am Fam Physician. 2010

Nucleic Acid Testing to Detect HBV

Infection in Blood DonorsTriplex nucleic acid testing detected potentially infectious HBV, along with HIV and

HCV, during the window period before seroconversion.

HBV vaccination appeared to be protective, with a breakthrough subclinical infection occurring with non-A2 HBV subgenotypes and causing clinically inconsequential outcomes.

nejm.236 org january 20, 2011

Acute liver failure (ALF) is an uncommon condition in which the rapid deterioration of liver function results in coagulopathy and alteration in the mental status of a previously healthy individual. Acute liver failure often affects young people and carries a very high mortality. The term acute liver failure is used to describe the development of coagulopathy, usually an international normalized ratio (INR) of greater than 1.5, and any degree of mental alteration (encephalopathy) in a patient without preexisting cirrhosis and with an illness of less than 26 weeks' duration.

Acute liver failure is a broad term and encompasses both fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) and subfulminant hepatic failure (or late-onset hepatic failure). Fulminant hepatic failure is generally used to describe the development of encephalopathy within 8 weeks of the onset of symptoms in a patient with a previously healthy liver. Subfulminant hepatic failure is reserved for patients with liver disease for up to 26 weeks before the development of hepatic encephalopathy.

The risk of mortality increases with the development of any of the complications, which include cerebral edema, renal failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), coagulopathy, and infection.

Grade

Level of ConsciousnessPersonality and Intellect

Neurologic Signs

Electroencephalogram (EEG) Abnormalities

0

Normal

Normal

None

None

Subclinical

Normal

Normal

Abnormalities only on psychometric testing

None

1

Day/night sleep reversal, restlessness

Forgetfulness, mild confusion, agitation, irritability

Tremor, apraxia, incoordination, impaired handwriting

Triphasic waves (5 Hz)

2

Lethargy, slowed responses

Disorientation to time, loss of inhibition, inappropriate behavior

Asterixis, dysarthria, ataxia, hypoactive reflexes

Triphasic waves (5 Hz)

3

Somnolence, confusion

Disorientation to place, aggressive behavior

Asterixis, muscular rigidity, Babinski signs, hyperactive reflexes

Triphasic waves (5 Hz)

4

Coma

None

Decerebration

Delta/slow wave activity

Grading of Hepatic Encephalopathy

Causes

Numerous causes of fulminant hepatic failure exist, but drug-related hepatotoxicity due to acetaminophen and idiosyncratic drug reactions is the most common cause of acute liver failure in the United States.

For nearly 15% of patients, the cause remains indeterminate.

Hepatitis A and B are the typical viruses that cause viral hepatitis and may lead to hepatic failure. Hepatitis C rarely causes acute liver failure. HDV (co-infection or superinfection with HBV) can lead to fulminant hepatic failure. HEV (often observed in pregnant women) in endemic areas is an important cause of fulminant hepatic failure.

Other atypical viruses can cause viral hepatitis and fulminant hepatic failure.

Cytomegalovirus

Hemorrhagic fever viruses

Herpes simplex virus

Paramyxovirus

Epstein-Barr virus

The incidence of acute fatty liver of pregnancy, frequently culminating in fulminant hepatic failure, has been estimated to be 0.008% (typically in the third trimester; preeclampsia develops in approximately 50% of these patients). However, the most common cause of acute jaundice in pregnancy is acute viral hepatitis, and most of these patients do not develop fulminant hepatic failure.

The one major exception to this is the pregnant patient who develops HEV infection and in whom an exposure history is usually remarkable for travel and/or residence in the Middle East, India and the subcontinent, Mexico, or other endemic areas. In these patients, progression to fulminant hepatic failure is unfortunately common and often fatal. In the United States, it is relatively uncommon but must be considered in the appropriate setting.

The HELLP syndrome occurs in 0.1-0.6% of pregnancies and is usually associated with preeclampsia.

Incidence of fulminant hepatic failure following other liver diseases is less well established.

Many drugs (both prescription and illicit) are implicated in the development of FHF. The list provided is incomplete, and only the more common agents are identified. Consult an appropriate pharmacy reference text if concerns exist regarding a specific medication. Idiosyncratic drug reactions may occur with virtually any medication. Fortunately, these appear to lead to fulminant hepatic failure only rarely, although they are the most common form of drug reaction to lead to fulminant hepatic failure (with the exception of acetaminophen poisoning).

Drug toxicity – Acetaminophen

Intentional or accidental overdose. In the US Acute Liver Failure (ALF) study, unintentional acetaminophen use accounted for 48% of cases, whereas 44% of cases were due to intentional use; in 8% of cases, the intention was unknown.Dose-related toxicity

May have greatly increased susceptibility to hepatotoxicity with depleted glutathione stores in the setting of chronic alcohol use (consider increased susceptibility due to chronic alcohol use)

Prescription medications (idiosyncratic hypersensitivity reactions)

Antibiotics (ampicillin-clavulanate, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, erythromycin, isoniazid, nitrofurantoin, tetracycline)

Antivirals (fialuridine)

Antidepressants (amitriptyline, nortriptyline)

Antidiabetics (troglitazone)

Antiepileptics (phenytoin, valproate)

Anesthetic agents (halothane)

Lipid-lowering medications (atorvastatin, lovastatin, simvastatin)

Immunosuppressive agents (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate)

(NSAIDs)

Salicylates (Reye syndrome)

Oral hypoglycemic agents (troglitazone)

Others (disulfiram, flutamide, gold, propylthiouracil)

Illicit drugs

Ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine [MDMA])Cocaine (may be the result of hepatic ischemia)

Herbal or alternative medicines

Ginseng

Pennyroyal oil

Teucrium polium

Chaparral or germander tea

Kawakawa

The following toxins are associated with dose-related toxicity:

Amanita phalloides mushroom toxin[14 ]

Bacillus cereus toxin

Cyanobacteria toxin

Organic solvents (eg, carbon tetrachloride)

Yellow phosphorus

The following are vascular causes of hepatic failure:

Ischemic hepatitis (consider especially if in the setting of severe hypotension or recent hepatic tumor chemoembolization)

Hepatic vein thrombosis (Budd-Chiari syndrome)

Hepatic veno-occlusive disease

Portal vein thrombosis

Hepatic arterial thrombosis (consider posttransplant)

The following metabolic diseases can cause hepatic failure:

Acute fatty liver of pregnancyAlpha1 antitrypsin deficiency

Fructose intolerance

Galactosemia

Lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase deficiency

Reye syndrome

Tyrosinemia

Wilson disease

Autoimmune disease (autoimmune hepatitis) can cause hepatic failure.

Malignancy can cause of hepatic failure.Primary liver tumor (usually hepatocellular carcinoma, rarely cholangiocarcinoma)Secondary tumor (extensive hepatic metastases or infiltration from adenocarcinoma, such as breast, lung, melanoma primaries [common]; lymphoma; leukemia)The following are miscellaneous causes of hepatic failure:

Adult-onset Still disease

Heat stroke

Primary graft nonfunction (in liver transplant recipients)

Differential Diagnoses

Other Problems to Be Considered

Acute fatty liver of pregnancyAdult-onset Still diseaseA phalloides mushroom poisoningB cereus toxinFructose intoleranceGalactosemiaHELLP syndrome of pregnancyHemorrhagic viruses (Ebola virus, Lassa virus, Marburg virus)Idiopathic drug reaction (hypersensitivity)Neonatal iron storage diseaseParamyxovirusPrimary graft nonfunction (in liver transplant recipients)TyrosinemiaYellow phosphorus poisoningAcetaminophen poisoning

Complete blood cell (CBC) count: Results may indicate thrombocytopenia.

PT and/or international normalized ratio (INR)Hepatic enzymes

Serum bilirubin

Serum ammonia

Serum glucose: levels may be very low and pose a serious hazard.

Serum lactate

Serum creatinine: levels may be elevated, signifying the development of hepatorenal syndrome or some other cause of acute renal failure.

Blood cultures

Serum-free copper

Serum phosphate

Viral serologies

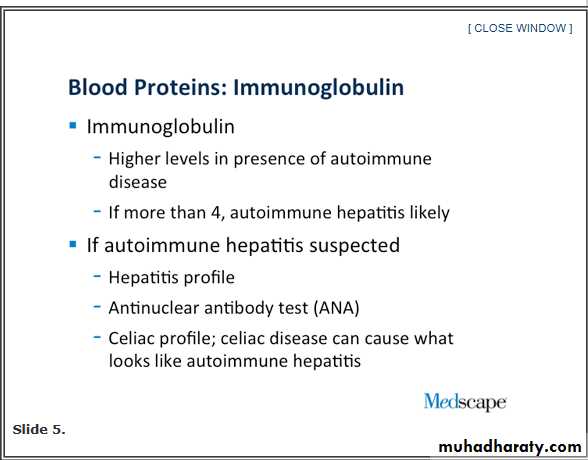

Autoimmune markers: Antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA), and immunoglobulin levels are important markers for a diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis.

Acetaminophen level

Drug screen: Consider a drug screen in a person who is an IV drug abuser.

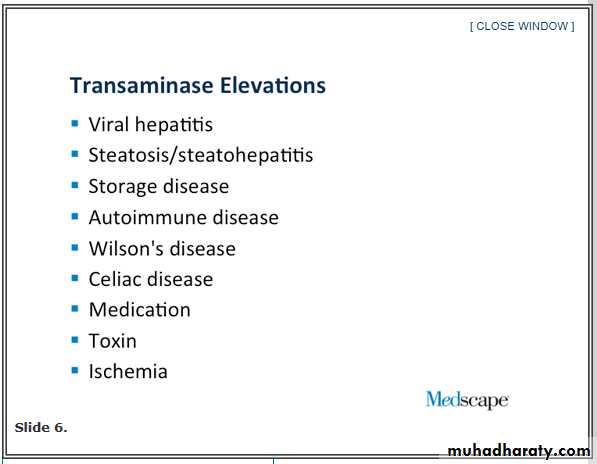

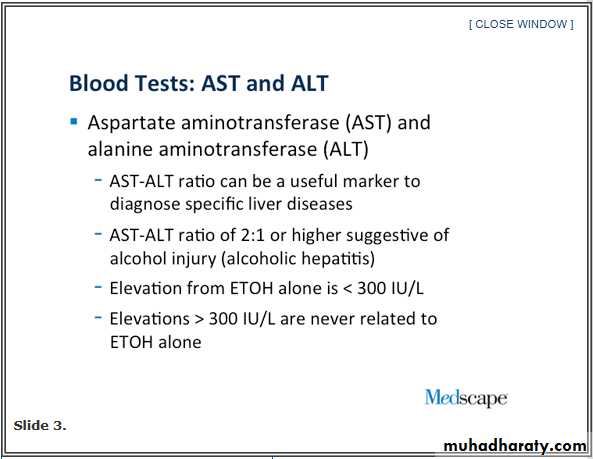

Hepatic enzymes Levels of the transaminases (aspartate aminotransferase [AST]/serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase [SGOT]

and alanine aminotransferase [ALT]/serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase [SGPT]) are often elevated dramatically as a result of severe hepatocellular necrosis.

In instances of acetaminophen toxicity (especially alcohol-enhanced), the AST level may be well over 10,000 U/L.

The alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level may be normal or elevated.

Serum glucose: levels may be very low and pose a serious hazard.

This results from impairments in glycogen production and gluconeogenesis.

Serum lactate .Arterial blood lactate levels either at 4 hours (>3.5 mmol/L) or at 12 hours (>3.0 mmol/L) are early predictors of outcome in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. levels are often elevated as a result of both impaired tissue perfusion (increases production) and decreased clearance by the liver.An increased anion gap metabolic acidosis is associated with this condition (although it may be accompanied by a respiratory alkalosis as a result of hyperventilation).

Arterial blood gases

(ABGs): These may reveal hypoxemia, which is a significant concern as a result of adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or other causes (eg, pneumonia).Serum creatinine:

levels may be elevated, signifying the development of hepatorenal syndrome or some other cause of acute renal failure.

Serum ammonia

This level may be elevated dramatically in patients with fulminant hepatic failure. Arterial blood is the best way to measure ammonia.The arterial serum ammonia level is most accurate, but venous ammonia levels are generally acceptable.

It does not exclude the possibility of another cause for mental status changes (notably increased ICP and seizures).

Treatment

Medical CareThe most important step is to identify the cause of liver failure.

Prognosis of acute liver failure is dependent on etiology. A few etiologies of acute liver failure demand immediate and specific treatment. It is also critical to identify those patients who will be candidates for liver transplantation.

The most important aspect of treatment in patients with acute liver failure is to provide good intensive care support. Patients with grade II encephalopathy should be transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for monitoring. As the patient develops progressive encephalopathy, protection of the airway is important.

Most patients with acute liver failure tend to develop some degree of circulatory dysfunction. Careful attention should be paid to fluid management, hemodynamics, metabolic parameters, and surveillance of infection. Maintenance of nutrition and prompt recognition of gastrointestinal bleeding are crucial. Coagulation parameters, CBC count, and metabolic panel should be checked frequently. Serum aminotransferases and bilirubin are generally measured daily to follow the course of infection. Intensive care management includes recognition and management of complications.

Airway protection

As the patients with fulminant hepatic failure drift deeper into coma, their ability to protect their airway from aspiration decreases.

Patients who are in stage III coma should have a nasogastric tube (NGT) for stomach decompression. When patients progress to stage III coma, intubation should be performed.

Short-acting benzodiazepines in low doses (eg, midazolam 2-3 mg) may be used before intubation or propofol (50 mcg/kg/min) may be initiated before intubation and continued as an infusion. Propofol is also known to decrease the cerebral blood flow and ICH. It may be advisable to use endotracheal lidocaine before endotracheal suctioning.

Encephalopathy and cerebral edema

Patients with grade I encephalopathy may sometimes be safely managed on a medicine ward. Frequent mental status checks should be performed with transfer to an ICU warranted with progression to grade II encephalopathy.Head imaging with CT scanning is used to exclude other causes of decline in mental status, such as intracranial hemorrhage.

Sedation should be avoided if possible; unmanageable agitation may be treated with short-acting benzodiazepines in low doses.

Patients should be positioned with the head elevated at 30°.

Efforts should be made to avoid patient stimulation. Maneuvers that cause straining or, in particular, Valsalva-like movements may increase ICP.

There is increasing evidence that ammonia may play a pathogenic role in the development of cerebral edema. Reducing elevated ammonia levels with enteral administration of lactulose might help prevent or treat cerebral edema.

ICP monitoring helps in the early recognition of cerebral edema.

The clinical signs of elevated ICP, including hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular respirations (Cushing triad), are not uniformly present; these and other neurologic changes, such as pupillary dilatation or signs of decerebration, evident only late in the course.

CT scanning of the brain does not reliably demonstrate evidence of edema, especially at early stages. A primary purpose of ICP monitoring is to detect elevations in ICP and reductions in cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP; calculated as mean arterial pressure [MAP] minus ICP) so that interventions can be made to prevent herniation while preserving brain perfusion.

The ultimate goal of such measures is to maintain neurologic integrity and prolong survival while awaiting receipt of a donor organ or recovery of sufficient functioning hepatocyte mass. Additionally, refractory ICH and/or decreased CPP is considered a contraindication to liver transplantation in many centers.

Cardiovascular monitoring

Homodynamic derangements consistent with multiple organ failure occur in acute liver failure. Hypotension (systolic, <80 mm Hg) may be present in 15% of patients. Most patients will require fluid resuscitation on admission. Intravascular volume deficits may be present on admission due to decreased oral intake or gastrointestinal blood loss. Hemodynamic derangement resembles that of sepsis or cirrhosis with hepatorenal syndrome (low SVR with normal or increased cardiac output). An arterial line should be placed for continuous blood pressure monitoring.A Swan–Ganz catheter should be placed and fluid replacement with colloid albumin should be guided by the filling pressure. If needed, dopamine or norepinephrine can be used to correct hypotension.

Management of renal failure: Hemodialysis may significantly lower the mean arterial pressure such that cerebral perfusion pressure is compromised. Continuous veno-venous hemofiltration is preferred.

Management of coagulopathy

In the absence of bleeding, it is not necessary to correct clotting abnormalities with fresh frozen plasma (FFP); the exception is when an invasive procedure is planned or in the presence of profound coagulopathy (INR >7). (PT and PTT become prolonged when plasma coagulation components are diluted to less than 30%, and abnormal bleeding occurs when they are less than 17%. One unit of FFP increases the coagulation factor by 5%; 2 units increase it by 10%.) FFP of 15 mL/kg of body weight or 4 units correct deficiency. If the fibrinogen level is very low (<80 mg/dL), consider cryoprecipitation.Recombinant factor VIIa may be used in patients whose condition is nonresponsive to FFP. It is used in a dose of 4 µg/kg IV push over 2-5 minutes. PT is normalized in 20 minutes and remains normalized for 3-4 hours.

Platelet transfusions are not used until the count is less than 10,000/µL or if an invasive procedure is being done and the platelet count is less than 50,000/µL. Six to 8 random donor platelets (1 random donor unit platelet/10 kg) will increase the platelet count to greater than 50,000/µL. The platelet count should be checked after 1 hour and 24 hours. Transfused platelets survive 3-5 days.

Managing poisonings (eg, acetaminophen, mushroom) requires specific treatment distinct from other, more general issues related to fulminant hepatic failure.Treat acetaminophen (paracetamol, APAP) overdose with N-acetylcysteine (NAC). Researchers theorize that this antidote works by a number of protective mechanisms. Early after overdose, NAC prevents the formation and accumulation of N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), a free radical that binds to intracellular proteins, nonspecifically resulting in toxicity.

NAC increases glutathione stores, combines directly with NAPQI as a glutathione substitute, and enhances sulfate conjugation. NAC also functions as an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant and has positive inotropic and vasodilating effects, which improve microcirculatory blood flow and oxygen delivery to tissues. These latter effects decrease morbidity and mortality once hepatotoxicity is well established.

The protective effect of NAC is greatest when administered within 8 hours of ingestion; however, when indicated, administer regardless of the time since the overdose. Therapy with NAC has been shown to decrease mortality in late-presenting patients with fulminant hepatic failure (in the absence of acetaminophen in the serum).

A phalloides mushroom intoxication is much more common in Europe as well as in California. Treat with IV penicillin G, even though its mode of action is unclear. Silibinin, a water-soluble derivative of silymarin, may be administered orally, and oral charcoal may be helpful by binding the mushroom toxin.

Surgical Care

Liver transplantation is the definitive treatment in liver failure, but a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this article. Although, 2 recent studies regarding liver transplantation are mentioned below, preoperative management is emphasized in this section. Lerut et al evaluated the effect of tacrolimus monotherapy in 156 adults receiving a primary liver graft, randomizing them to receive tacrolimus-placebo and tacrolimus-low-dose, short-term (64 days), steroid immunosuppression. There were no exclusion criteria at randomization, and all patients had a 12-month follow-up (range, 12-84).[20 ]The investigators found that the patients in the tacrolimus-steroid group had higher 3- and 12-month survival rates, as well as higher 12-month graft survival rates, relative to those in the tacrolimus-placebo group. Not only were fewer patients in the tacrolimus-steroid group administered rejection treatment at 3 and 12 months, but fewer individuals in this group and the group of 145 patients transplanted without artificial organ support demonstrated corticosteroid-resistant rejection at 3 and 12 months.[20

By 1 year, 82% (64/78) of those in the tacrolimus steroid group were on tacrolimus monotherapy compared with 78.2% (61/78) of those in the tacrolimus-placebo group (P = 0.54). However, when considering the 74 tacrolimus-steroid and 67 tacrolimus-placebo survivors, rates of monotherapy were lower in the tacrolimus-steroid group versus the tacrolimus-placebo group (P = 0.39).[20 ]

Lerut et al concluded that tacrolimus monotherapy can be achieved safely without compromising graft nor patient survival in a primary, even unselected, adult liver transplant population and that such a strategy may lead to further large-scale minimization studies in liver transplantation.[20 ]The investigators attributed the higher incidence of early corticosteroid-resistant rejection in the tacrolimus-placebo group to the significantly higher number of patients transplanted while being on artificial organ support and recommended that the monodrug immunosuppressive strategy would require adaptation in this setting.[20 ]

In a retrospective study, Taketomi et al evaluated donor safety in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation by establishing a selection criterion for donors in which the left lobe was the first choice of graft.[21 ]Two hundred and six consecutive donors were divided into 2 groups according to the graft type (left [n = 137] vs right lobe [n =69]). Mean intraoperative blood loss was significantly increased in the left lobe donors compared with right lobe donors; however, mean peak postoperative total bilirubin levels and duration of hospital stay after surgery were significantly less for those in the left lobe group (P <0.05).[21 ]

No donor died or suffered a life-threatening complication during the study period. The investigators noted that logistic regression analysis revealed that only graft type (left vs right lobe) was significantly related to the occurrence of biliary complications (odds ratio 0.11; P = 0.0012).[21 ]However, there were no significant differences regarding the cumulative overall graft survival rates between the recipients with left lobe grafts and those with right lobe grafts.

In selected patients for whom no allograft is immediately available, consider support with a bioartificial liver. This is a short-term measure that only leads to survival if the liver spontaneously recovers or is replaced.

In the future, hepatocyte transplantation, which has shown dramatic results in animal models of acute liver failure, may provide long-term support, but it remains investigational.

Artificial liver support systems

Artificial liver support systems can be divided into 2 major categories: biologic (bioartificial) and nonbiologic.The bioartificial liver is composed of a dialysis cartridge with mammalian or porcine hepatocytes filling the extracapillary spaces. These devices have undergone controlled trials. One multicenter trial reported improved short-term survival for a subgroup of patients with acute liver failure who were treated with a porcine hepatocyte-based artificial liver.[25 ]

Nonbiologic extracorporeal liver support systems, such as hemodialysis, hemofiltration, charcoal hemoperfusion, plasmapheresis, and exchange transfusions, have been used; however, no controlled study has shown long-term benefit.

These modalities permit temporary liver support until a suitable donor liver is found. Although extracorporeal hemoperfusion of charcoal and other inert substances provide some measure of excretory function, no synthetic capacity is provided.

Among the liver support systems currently available, albumin dialysis using the molecular adsorbent recirculating system (MARS) is the one that has been most extensively investigated. In this device, blood is dialyzed across an albumin-impregnated membrane against 20% albumin. Charcoal and anion exchange resins columns in the circuit cleanse and regenerate the albumin dialysate.

Clinical studies have shown that it improves hyperbilirubinemia and encephalopathy.

Two other systems based on the removal of albumin bound toxins, the Prometheus, using the principle of fractionated plasma separation and adsorption (FPSA), and the single pass albumin dialysis (SPAD), are also undergoing clinical studies for acute liver failure.Currently available liver support systems are not routinely recommended outside of clinical trials.

Diet

Patients with acute liver failure are, by necessity, nothing by mouth (NPO). They may require large amounts of IV glucose to avoid hypoglycemia.

When enteral feeding via a feeding tube is not feasible (eg, as in a patient with paralytic ileus), institute total parenteral nutrition (TPN). (See also Nutritional Requirements of Adults Before Transplantation and Nutritional Requirements of Children Prior to Transplantation).

Restricting protein (amino acids) to 0.6 g/kg body weight per day was previously routine in the setting of hepatic encephalopathy, but this may not be necessary.

Activity

Bedrest is recommended.Medication

Multiple medications may be necessary in patients with acute liver failure because of the wide variety of complications that may develop from fulminant hepatic failure. Decreased hepatic metabolism and the potential for hepatotoxicity become central issues. Antidotes that effectively bind or eliminate A phalloides toxin and toxic metabolites of acetaminophen are essential.

Acetaminophen ingestion of more than 10 g may be hepatotoxic due to formation of a highly reactive toxic intermediate metabolite, which is ordinarily metabolized further in the presence of glutathione to N -acetyl-p-aminophenol-mercaptopurine. Administering NAC permits restitution of intrahepatic glutathione. NAC is most effective when administered within 12-20 hours following acetaminophen overdose. Never administer aminoglycosides and NSAIDs, because the potential for nephrotoxicity is exaggerated greatly in this setting.

Complications

Hepatic encephalopathyManage hepatic encephalopathy in the conventional way, by providing lactulose and avoiding sedatives. In the late stages of encephalopathy, avoid providing lactulose by mouth or nasogastric tube without previous intubation, considering the risk of aspiration.Hepatic encephalopathy is not truly a complication because it is required for the diagnosis of fulminant hepatic failure, but evolution to higher stages of hepatic encephalopathy may result in patients losing their abilities to maintain their airways.

Cerebral edema

The occurrence of cerebral edema and ICH in patients with acute liver failure is related to the severity of encephalopathy. Cerebral edema is seldom observed in patients with grades I-II encephalopathy. The risk of edema increases to 25-35% with progression to grade III and to 65-75% (or more) in patients reaching grade IV coma.Patients in the advanced stages of encephalopathy require close follow-up care. Monitoring and management of hemodynamic and renal parameters, as well as glucose, electrolytes, and acid/base status, become critical. Frequent neurologic evaluation for signs of elevated ICP should be conducted.

ICP monitoring

ICP monitoring helps in the early recognition of cerebral edema. The clinical signs of elevated ICP, including hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular respirations (Cushing triad), are not uniformly present; these and other neurologic changes, such as papillary dilatation or signs of decerebration, are typically evident only late in the course.

CT scanning of the brain does not reliably demonstrate evidence of edema, especially in the early stages. A primary purpose of ICP monitoring is to detect elevations in ICP and reductions in CPP, so that interventions can be made to prevent herniation while preserving brain perfusion.

The ultimate goal of such measures is to maintain neurologic integrity and to prolong survival while awaiting receipt of a donor organ or recovery of sufficient functioning hepatocyte mass.

Additionally, refractory ICH and/or decreased CPP is considered a contraindication to liver transplantation in many centers.

In patients with grade III or IV encephalopathy, consider placement of ICP monitors.

Correct coagulopathy and bleeding tendencies with the use of FFP and platelet infusion.If an ICP monitor is placed, ICP should be maintained below 20-25 mm Hg, if possible, with CPP maintained above 50-60 mm Hg. Support of systemic blood pressure may be required to maintain adequate CPP.

ICH is managed initially by the use of mannitol. Osmotic diuresis with IV mannitol is effective in the short term in decreasing cerebral edema. Administration of IV mannitol (in a bolus dose of 0.5-1 g/kg or 50-100 g) is recommended to treat ICH in acute liver failure. The dose may be repeated once or twice, as needed, provided serum osmolality has not exceeded 320 mOsm/L. Volume overload is a risk with mannitol use in patients with renal impairment and may necessitate the use of dialysis to remove excess fluid.

Other therapies used to decrease ICH but not routinely recommended may be considered in refractory ICH.

A controlled trial of administration of 30% hypertonic saline, 5-20 mL/h, to maintain serum sodium levels of 145-155 mmol/L in patients with acute liver failure and severe encephalopathy suggested that induction and maintenance of hypernatremia may be used to prevent the rise in ICP values.

Barbiturate agents (thiopental or pentobarbital) may also be considered when severe ICH does not respond to other measures; administration has been shown to effectively decrease ICP. Significant systemic hypotension frequently limits their use and may necessitate additional measures to maintain adequate mean arterial pressure.Thiopental 5-10 mg/kg loading dose followed by 3-5 mg/kg IV infusion.Pentobarbital 3-5 mg/kg IV loading dose followed by 1-3 mg/kg/h infusion.

Seizures, which may be seen as a manifestation of the process that leads to hepatic coma and ICH, should be controlled with phenytoin. The use of any sedative is discouraged in light of its effects on the evaluation of mental status. Only minimal doses of benzodiazepines should be used given their delayed clearance by the failing liver. Seizure activity may acutely elevate and may also cause cerebral hypoxia and, thus, contribute to cerebral edema.

Hemorrhage

This develops as a result of the profoundly impaired coagulation that manifests in these patients.Correct coagulopathy, as earlier outlined.

The transfusion requirements for coagulation products (FFP, platelets) may be enormous. Multiple transfusions with packed red blood cells may be needed.

Gastrointestinal bleeding may develop from esophageal, gastric, or ectopic varices as a result of portal hypertension. Portal hypertensive gastropathy and stress gastritis may also develop.

Any minor trauma may result in extensive percutaneous bleeding or internal hemorrhage.

Consider retroperitoneal hemorrhage if large transfusion requirements are not matched by an obvious blood loss.

Infection prophylaxis and treatment

Periodic surveillance cultures should be performed to detect bacterial and fungal infections.

Empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics and antifungals should be given in the following circumstances:

Progressive encephalopathy (All patients listed for transplantation start antibiotics.)

Signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) (temperature, >38ºC or <36ºC; white blood cell [WBC] count, >12,000/μL or <4000/μL; pulse rate, >90 bpm)

Persistent hypotension

Zosyn and fluconazole should be the initial choice. In hospital-acquired IV catheter infections, consider vancomycin.

Renal electrolyte and acid-base imbalances

Acute renal failure is a frequent complication in patients with acute liver failure and may be due to dehydration, hepatorenal syndrome, or acute tubular necrosis.Maintain adequate blood pressure, avoid nephrotoxic medications and NSAIDs, and promptly treat infections.

When dialysis is needed, continuous (ie, continuous venovenous hemodialysis [CVVHD]) rather than intermittent renal replacement therapy is preferred.

Metabolic concerns

Alkalosis and acidosis occur; identify and treat the underlying cause.Base deficits can be corrected by THAM solution (tromethamine injection), which prevents a rise in carbon dioxide, osmolality, and serum sodium.

Severe hypoglycemia occurs in approximately 40% of patients with fulminant hepatic failure. Although hypoglycemia occurs more frequently in children, it needs to be monitored in adult patients as well.

Blood sugars should be maintained in the range of 60-200 mg/dL with the infusion. Use 10% dextrose solution and glucose monitoring.

Phosphate, magnesium, and potassium levels are low and require frequent supplementation.

Prognosis

Prognosis is highly dependent on the inciting cause of fulminant hepatic failure. Prognostic indices have been developed to identify patients who require liver transplantation. The development of complications is the other factor that largely determines survival.Viral hepatitis

Approximately 50-60% of patients with fulminant hepatic failure due to HAV infection survive.

These patients account for a substantial proportion (10-20%) of the pediatric liver transplants in some countries, despite the relatively mild infection observed in many children infected with HAV.

The outcome for patients with fulminant hepatic failure as the result of other causes of viral hepatitis is much less favorable.

Acetaminophen toxicity

Fulminant hepatic failure due to acetaminophen toxicity generally has a relatively favorable outcome, and prognostic variables permit reasonable accuracy in determining the need for OLT.Patients presenting with deep coma (hepatic encephalopathy grades 3-4) have increased mortality when compared with those with milder encephalopathy.

An arterial pH of less than 7.3 and either a PT greater than 100 seconds or serum creatinine greater than 300 mcg/mL (3.4 mg/dL) are independent predictors of a poor prognosis.

Non–acetaminophen-induced fulminant hepatic failure

A PT greater than 100 seconds and any 3 of the following 5 criteria are independent predictors[10 ]:(1) age younger than 10 years or older than 40 years; (2) fulminant hepatic failure due to non-A, non-B, non-C hepatitis; halothane hepatitis; or idiosyncratic drug reactions;

(3) jaundice present longer than 1 week before onset of encephalopathy;

(4) PT greater than 50 seconds; or

(5) serum bilirubin greater than 300 mmol/L (17.5 mg/dL).Once these patients are identified, arrange appropriate preparations for OLT.

The above criteria, developed at King's College Hospital in London, have been validated in other centers; however, significant variability occurs in the patient populations encountered at any center, and this heterogeneity may preclude widespread applicability.

Other prognosticating tests have been proposed. Reduced levels of Gc-globulin (a molecule that binds actin) have been reported in fulminant hepatic failure, and a persistently increasing PT portends death. These and other parameters have not been widely validated yet.

Wilson disease: Wilson disease presenting as fulminant hepatic failure is almost uniformly fatal without OLT.

We are always taught that there is a disproportion in patients that have alcohol [injury]. The AST goes up, and the ALT lags behind. There is a 2:1 ratio that we are all taught and is somewhat strongly suggestive of alcohol injury. Why is that? It is because of where the enzymes live in the cell. For alcohol injury, it is a subcellular enzyme. It does not necessarily require the whole cell to be killed to have this released; but, the ALT is a cytosolic component to the enzyme, so you really have to kill the whole cell to get the ALT released.

The injury from alcohol does not necessarily have to kill the whole cell, so the AST goes up, and the ALT lags behind, in particular, unless the whole cell is killed. That can happen with alcohol, too.

I always look at the immunoglobulin fraction. This is helpful because it may pinpoint you very quickly to a patient with autoimmune hepatitis. The immunoglobulin fraction is something you can easily calculate; it is simple subtraction. You start with the total protein and then subtract the albumin. It should be less than 4. If it is less than 4, autoimmune hepatitis is less likely, if it is over 4, you are starting to think very quickly about autoimmune hepatitis.

We are seeing an incredible number of people with celiac disease, and their only manifestation, as it was in this case, potentially, was that they just had their blood drawn and their liver tests are up. Celiac disease can cause what looks like an autoimmune-type hepatitis pattern. It is something that we are seeing more and more. It has responded nicely to control of celiac disease. I would consider a celiac profile, maybe not on the first pass of this patient, but, if there is persistent elevation, I would consider it on the second pass.

you should consider Wilson's disease. It is something that we used to tell people, you never screen them over 40 .We do see that Wilson's disease will typically present earlier in life with liver disease. In patients younger than 25-30 years, Wilson's disease may present with hemolysis and liver test abnormalities. Wilson's disease can cause fulminant hepatic failure. Older patients, that is, older than 35 years or so, may present more with neurologic sequelae. We have seen Wilson's disease reported now in patients in their seventh decade of life. A ceruloplasmin is an easy one to get, and I never fault the residents for ordering a ceruloplasmin even on patient like this.

By the Numbers: Liver Disease and Patient Age

What else do I do as far as looking at these people? I think about different ages.

If a young patient comes in (the patient in their 20s, or sub 20s), you think about things like Wilson's disease and autoimmune hepatitis. That would be something that you really could not afford to miss.

When [patients] get into their 20s and 30s, you start to think about things like hemochromatosis, Wilson's disease continues, and also viral hepatitis.

For patients in the 30s, 40s, and early 50s, you start to worry about things like primary biliary cirrhosis, especially in women. The tip here is that these patients will typically have pruritus when they come in. It is very common to see pruritus, even though they are not even quite jaundice.

Interestingly, intrahepatic cholestasis, meaning not obstructive biliary disease, is very likely to cause pruritus early as opposed to a patient who comes in and is profoundly jaundice from a malignancy or something.

Those patients get pruritus (itching) later in the stages of their disease, as opposed to [patients with] primary biliary cirrhosis who may have [pruritus] very early in their presentation.

So for patients in the 30s, 40s, and 50s, I am also thinking about autoimmune hepatitis. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is one we had not mentioned yet, but it is simple enough to look for. It typically does not present as liver disease until in the fourth, maybe fourth to fifth, decade, so it is later in presentation. A simple test here is a serum protein electrophoresis, looking at the Alpha-1 level, in particular. If you see any abnormalities, then go straight to an Alpha-1 level, it is a lot more expensive to order that test up front, so I do not typically do that. I order a serum protein electrophoresis.

For patients in the 50s, 60s, and 70s, you start to always think about bad things, such as infiltrative diseases and metastatic diseases. There is second peak for autoimmune hepatitis in the 50s and 60s. Think again about primary biliary cirrhosis. Think about other things, particularly drug-induced abnormalities, as these patients are exposed to more drugs as they age.

One thing that we start to see in the older patient population too is, as they may have a component of congestive failure, we may see some elevation there; this more or less creates an ischemic pattern of injury, and, in that patient, I may also look at hepatic portal venous flow and do hepatic duplex, looking at their right heart influence on the hepatic flow.

An Interferon-Free Regimen for Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection

Combining a protease inhibitor and a polymerase inhibitor led to declines in viral load, even among patients with previous treatment failure.In 2011, protease inhibitors will become available for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Previous studies have shown that adding one of these agents to peginterferon plus ribavirin improves the rate of sustained virologic response (SVR) but also increases the likelihood of adverse effects and withdrawal (JW Gastroenterol Apr 7 2010 and JW Gastroenterol Aug 20 2010).

Now, in the industry-funded INFORM-1 trial, researchers have evaluated the safety, tolerability, and antiviral activity of an interferon-free regimen consisting of two new oral anti-HCV agents: danoprevir (an NS3/4A protease inhibitor) and RG7128 (a nucleoside polymerase inhibitor).

Patients with HCV genotype 1 infection (some treatment naive, some with previous treatment failure) were randomized to receive placebo or a combination of danoprevir (100 mg or 200 mg every 8 hours or 600 mg or 900 mg twice daily) plus RG7128 (500 mg or 1000 mg twice daily) for 13 days. A total of 73 patients received the combination treatment, and 14 received placebo. The mean baseline viral load was 6.4 log10 IU/mL.

By the end of treatment, the median change in viral load for the various dosing groups ranged from –3.7 to –5.2 log10 IU/mL, with 18 patients achieving undetectable viral loads.

At the highest dosing combination studied (1000 mg of RG7128 twice daily and 900 mg of danoprevir twice daily), the median decline in viral load was similar between treatment-naive patients and those with previous treatment failure (–5.2 and –4.9 log10 IU/mL, respectively). Overall, the regimen was well tolerated, with no safety issues or resistance concerns identified.

Comment: This proof-of-concept study demonstrates the short-term benefits of combining a polymerase inhibitor and a protease inhibitor for the treatment of HCV. Significant declines in viral load were seen at 14 days, even among patients with previous treatment failure, and some patients achieved undetectable viral loads. Longer studies are needed to determine whether interferon-free regimens such as this one will achieve SVR and whether resistance will be an issue. In the meantime, this study gives hope that HCV might eventually be treatable with a well-tolerated, oral, interferon-free regimen.

Published in Journal Watch Gastroenterology November 19, 2010

In cirrhotic patients, esophageal variceal bleeds are common, with a mortality rate for first bleed reaching 50%. Endoscopic injection sclerotherapy is a well-established method in the management of acute bleeding from esophageal varices; however, it is not recommended for prophylaxis of the first episode of variceal hemorrhage. Currently, endoscopic variceal ligation has replaced endoscopic injection sclerotherapy as the endoscopic treatment of choice of bleeding esophageal varices.

Beta-Blockers Alone May Be Preferred to Prevent First Variceal Bleeding

MedscapeCME 06/18/2010;

In addition, nonselective beta-blockers have been well documented in reducing the risk for variceal bleed.

Thus, both nadolol and ligation have proven to be effective in the prophylaxis of first variceal bleeding. It has been suggested that combining the 2 approaches may enhance their effectiveness; however, the results of this combination are still unknown. This aim of this study was to evaluate the effects and safety of combining nadolol with ligation in the primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding.

Cirrhotic patients with high-risk esophageal varices but without a bleeding history were considered for enrollment.

140 eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive band ligation plus nadolol (combined group, 70 patients) or nadolol alone (nadolol group, 70 patients).

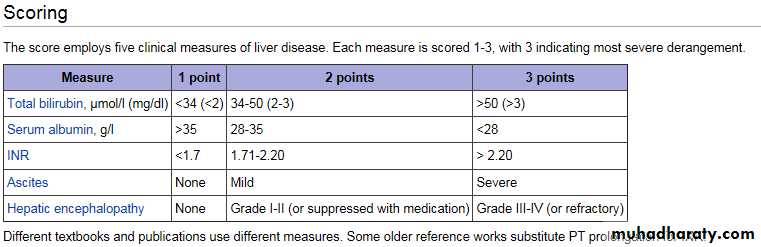

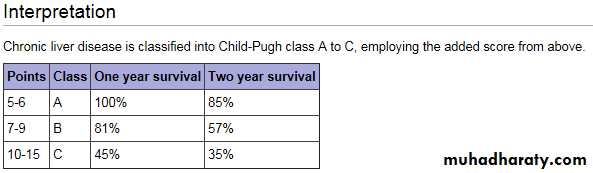

The severity of liver disease of each patient was assessed at the time of presentation according to Pugh's modification of Child's classification.

Patients received regular ligation treatment at an interval of 4 weeks until all varices were obliterated or were too small to be ligated.

Nadolol was administered at a dose to reduce 25% of the pulse rate in both the combined group and the nadolol group.

Both groups were comparable in baseline data.

In the combined group, 50 patients (71%) achieved variceal obliteration.

The mean dose of nadolol was 52 ± 16 mg in the combined group and 56 ± 19 mg in the nadolol group.

During a median follow-up of 26 months, 18 patients (26%) in the combined group and 13 patients (18%) in the nadolol group experienced upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding (P = .42).

Esophageal variceal bleeding occurred in 10 patients (14%) in the combined group and 9 patients (13%) in the nadolol group (P = .60).

No relationship existed between esophageal variceal bleeding and Child-Pugh class or the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score in both the treatment groups.

Multivariate analysis revealed that only bilirubin (odds ratio [OR], 1.28; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08 - 1.52; P < .005) was the factor predictive of first rebleeding.

Adverse events were noted in 48 patients (68%) in the combined group and 28 patients (40%) in the nadolol group (P = .06).

16 patients in each group died. The most common cause of death was hepatic failure, followed by sepsis.

The cause of death ascribed to variceal bleeding occurred in 1 patient in the combined group and 2 patients in the nadolol group.

Multivariate analysis revealed that ascites and encephalopathy were predictive factors of mortality.

Additionally, patients with a higher baseline MELD score at enrollment in the nadolol group had a higher mortality rate.

Clinical Implications

Both nadolol and ligation have been proven to be effective in the prophylaxis of first variceal bleeding.This study demonstrated that the addition of ligation to nadolol may increase adverse events and did not enhance the effectiveness in the prophylaxis of first variceal bleeding.

• Drugs that can cause jaundice:

• Aldomet• Aminosalicylate sodium

• Chemotherapy drugs:

• The administration of medicines that kill cancer cells.

• Erythromycin

• Flucytosine

• Oral contraceptives

• Oral diabetes medicines (e.g. tolbutamide, chlorpropamide)

• Phenothiazines:

• Chlorpromazine (Thorazine)

• Fluphenazine (Prolixin)

• Trifluoperazine (Stelazine)

• Perphenazine (Trilafon)

• Thioridazine (Mellaril)

• Prochlorperazine (Compazine)

Propylthiouracil

Rifampin

Steroids:

Prednisone

Medrol

Sulfa drugs:

Bactrim

Septra

Testosterone

Tiopronin

Treatment for hepatitis B

BMJ 5 January 2010

Hepatitis B virus is estimated to have infected 350 million individuals globally, accounting for over

500 000 deaths each year. An effective and widely available vaccine provides protection from infection, but treatment is rarely curative. Recent developments in antiviral treatment have brought the opportunity for greatly improved management of those chronically infected with hepatitis B virus, and for patients infected both with HIV and hepatitis B virus there is now the potential to treat both viruses with a simplified combination of drugs.

The screening test for hepatitis B is the presence in blood of hepatitis B surface antigen.

Chronic hepatitis B infection is defined as persistence of hepatitis B surface antigen for

more than six months.

In patients without evidence of hepatitis B surface antigen where it is important to know whether there has been previous infection—for example, in those about to receive chemotherapy—previous exposure can be assessed by presence of hepatitis B core antibody.

• Investigations under specialist careInvestigations related to hepatitis B

• Surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis Be antigen (HBeAg), anti-HBe, anti-HBs, anti-HBcore• Quantitative hepatitis B virus DNA

• Hepatitis B virus genotype (for those considered for interferon)

• Delta virus serology

• General

• Full blood count

• Bilirubin

• Liver enzymes

• Clotting

Ferritin

Lipid profile

Autoantibody screen

Caeruloplasmin

Tests for hepatitis C virus and HIV

Screening for liver cancer

Ultrasonography

fetoprotein

Staging of disease

Fibroelastography

Liver biopsy

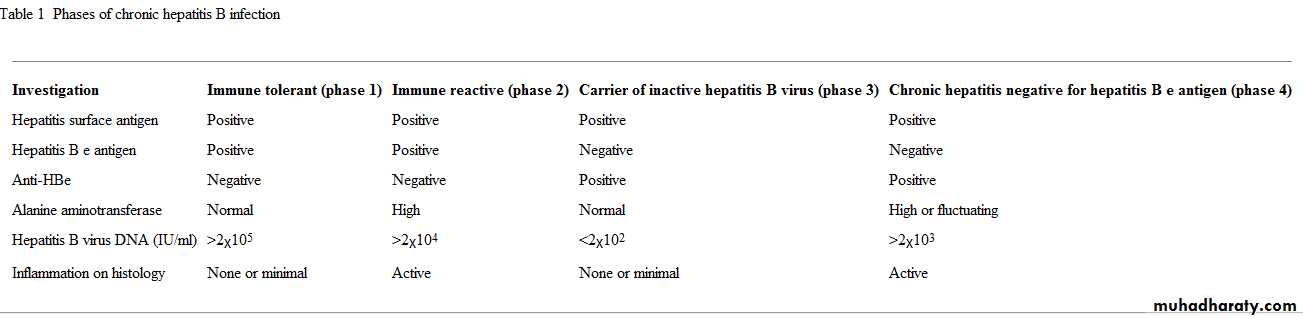

• The distinction between hepatitis B viral activity and liver disease related to hepatitis B virus is important and sometimes the source of confusion. Individuals infected in childhood (which is most of those infected worldwide) often experience a period of immunotolerance during which the virus is highly replicative but minimal liver damage occurs.The infection will eventually progress to a hepatitic phase associated with inflammation and liver fibrosis.

Spontaneous resolution of the hepatitic phase may occur with loss of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and appearance of anti-HBe. This results in an "asymptomatic" phase with normal liver functions tests and low viral load (<2x103 IU/ml). Many adult patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in European settings will present in this phase of disease. In the past they may have been falsely reassured and discharged. It is now clear that viral reactivation will occur in 15-20% of this group of patients, causing HBeAg negative hepatitis

The role of liver biopsy

Liver biopsy continues to play an important role in determining who should start treatment. The information it can provide on the aetiology and severity of liver disease cannot easily be substituted by non-invasive tests. Different histological grading systems are used in different centres. The most commonly used are the Ishak and Metavir scores, but all systems provide some measure of inflammation (current activity) and fibrosis (morechronic scarring).Although in the past physicians and patients have expressed concerns about the safety of liver biopsy, developments in technology, particularly ultrasonography, mean that complications from the procedure are now rare when the procedure is carried out regularly.15 Newer, non-invasive imaging methods, particularly the FibroScan technique,16 are gaining favour in routine practice, though validation data are still needed in different settings.

The hope has been that non-invasive biomarkers of liver fibrosis, including proprietary tests such as ELF (enhanced liver fibrosis), FibroTest, and others,17 can substitute for biopsy, which at best is unpleasant. However, the imperfect performance of non-invasive markers in clinical practice means they have yet to be widely adopted and further improvements are a priority for research.

What is the goal of treatment?

The goal of treatment for individuals with chronic hepatitis B virus infection is to prevent morbidity and mortality related to the disease. This can be achieved with a finite course of interferon therapy or long term viral suppression with nucleoside/nucleotide analogues.7 There are recommended surrogate end points for treatment.13 Loss of hepatitis B surface antigen may be achieved, and this can be regarded as remission of the infection.In patients positive for HBeAg, seroconversion to become negative for HBeAg or positive for anti-HBe is associated with sustained suppression of hepatitis B virus DNA after treatment withdrawal and can be considered an end point of therapy. However, cohort studies have identified the importance of high viral load in determining disease progression. The availability of newer treatments means that increasing emphasis is placed on the need to suppress viral load to below the limit of detectable DNA (usually below 10-15 IU/ml, depending on the assay), with long term therapy.

Who should be treated and with what?