Cancer and genetics: an up to date guide

د. حسين محمد جمعةاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2010

Key points

5-10% of cancers are thought to be caused by genetic factorsCancer genes greatly increase the risk of a person developing cancer

The genes that predispose to cancer are not on the X or Y chromosomes

The family history is the most reliable way of assessing the familial risk of developing cancer

You should refer patients that you have identified as having a significantly increased risk of developing cancer for screening and/or specialist assessment of the family history

Clinical tips

Mutations in genes that predispose a person to develop cancer can be carried by men and women, but they may have different effects in different sexesMammography does not prevent breast cancer, but it may be able to improve prognosis by identifying it at an early stage.

Prophylactic mastectomy in women at high genetic risk of developing breast cancer reduces the risk of breast cancer by up to 90%, depending on the type of surgery undertaken.

Introduction

Most cancer is not caused by genetic factors. Genes that greatly increase the risk of developing cancer are estimated to be responsible for 5-10% of the incidence of common cancers (breast cancer and colorectal cancer). These genes are high penetrance genes, which means they are very likely to cause clinical manifestations.The remaining 90-95% of cancers are thought to be due to a combination of genetic factors that are relatively weak and non genetic factors, including age and environmental influences such as smoking and alcohol.

In diseases such as breast cancer, where genes with high penetrance have been discovered, it is possible to test for these genes in selected individuals, on the NHS. Genetic testing is complex and expensive. Its availability is currently limited to families who have a significant, usually greater than 20%, chance of carrying a mutation.

Jargon buster

Mutation: a change in the DNA code of a gene that prevents the gene from producing a fully functional protein.Cancer genes: the genes that greatly increase the risk of cancer are ordinary human genes that have mutations in critical parts of their genetic code.

Penetrance: the likelihood that a person who carries a particular genetic make up (genotype) will have associated clinical manifestations (phenotype).

High penetrance genes: a mutated gene that is very likely to cause clinical manifestations.

Low penetrance genes: a mutated gene that has a small chance of causing clinical manifestations

Why is cancer genetics important?

There is growing interest in the subject of cancer genetics. Patients with a family history of cancer often ask healthcare professionals about the importance of their family history.A number of factors have contributed to this growing interest. These include:

The discovery of dominantly inherited genes with high penetrance such as BRCA1 and BRCA2. People who carry the mutated genes have an increased risk of developing cancer.

The activity of cancer charities, such as Cancerbackup and Breast Cancer Care, which have made the public more aware of the significance of having a family history of cancer

Media coverage of topics related to cancer genetics, including the discovery of certain breast cancer genes with low penetrance, such as CHEK2 and PALB2.

Jargon buster

Autosomal dominant inheritance:this means that you only need to inherit a mutation from one parent in order to inherit the increased risk of developing cancer.

What are cancer genes?

The genes that are commonly referred to as cancer genes are human genes that are normally involved in critical cellular functions such as control of the cell cycle and DNA repair.

When there is a mutation in one of these genes, the gene does not function normally. For the person who carries the mutation, this functional failure leads to an increased risk of them developing cancer.

The risk of cancer that these genes confer is organ specific. For example, mutations in the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 increase the risk of the carrier developing breast and ovarian cancer. They do not cause a generalised increase in the risk of developing all types of cancer.

Although these mutated genes may be responsible for the development of cancer, it is useful to think of them as genes that predispose a person to develop cancer. People who carry the mutated genes have an increased risk of developing cancer, but some may never develop cancer.

Most cancer genes with mutations are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. So a mutation in only one copy of a gene will increase the risk of a person developing cancer.

Cancers which are most likely to have a genetic cause

Breast and ovarian cancerTwo high penetrance genes - BRCA1 and BRCA2 - are responsible for less than 10% of breast cancers

Although BRCA1 and BRCA2 are usually called the breast cancer genes, they should really be called the breast and ovarian cancer genes, because they increase the risk of developing both breast and ovarian cancer

Women who carry mutations in either BRCA1 or BRCA2 have a lifetime risk of developing breast cancer of up to 85%. The UK population risk is about 11%

These women also have a lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer of up to 60%. The UK population risk is less than 2%

About one in 400 people carry a mutation in one of these genes. The risk of carrying a mutation in one of these genes is much higher (about one in 50) for Ashkenazi Jews

Jargon buster

Population risk and near-population risk: individuals whose risk of developing a disease is similar (not more than twice) the average person's risk are said to be at population risk or near-population risk.Above-population risk and increased risk: individuals whose risk of developing a disease is more than twice the average person's risk are said to be at above-population risk or increased risk.

Colorectal cancer

People with Lynch syndrome (sometimes known as hereditary non polyposis colon cancer or HNPCC) have an increased risk of developing cancers of the colorectum, endometrium, ovaries, and renal tractMutations in several genes (including MLH1, MSH2, MSH6) can cause Lynch syndrome

Lynch syndrome accounts for about 5% of patients with colorectal cancer.

There are other rare genetic syndromes that cause cancer. Examples include:

Familial adenomatous polyposis - patients have multiple polyps which almost invariably become malignant

Ninety five per cent of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis will develop colorectal cancer before the age of 45 if they do not have prophylactic colectomies

Von Hippel Lindau disease - patients may develop renal cell carcinoma and other non malignant tumours such as retinal angiomas.

Clusters of cancer in families which are not explained by the genes that have been identified so far

With our current state of understanding we are unable to explain why there are some families who have clusters of cancer. Some of these familial clusters are probably just bad luck, or due to the fact that family members may be exposed to similar environmental factors. But some appear to have a genetic basis which has not yet been elucidated.

When do people tend to become concerned about whether they have a genetic predisposition to developing cancer?

Recent deaths within a family are an important trigger for concern. People whose relatives have cancer or have died of cancer may be worried that they too could develop cancer.Women who are considering hormonal contraception may be concerned about their risk of developing breast cancer.Patients who have cancer themselves may be concerned about whether other members of their family might be at risk.

Patients who are enrolled in programmes for cancer screening may become aware that their family history may predispose them to developing cancer

Identifying people who have an increased genetic risk of developing cancer

The best way of identifying people who are at increased genetic risk of developing cancer is by taking a family history of cancer.Jargon buster

First degree relatives: mother, father, daughter, son, sister, brother.Second degree relatives: grandparent, grandchild, aunt, uncle, niece, nephew, half sister, and half brother.

Third degree relatives: first cousins.

To make a thorough assessment of familial cancer risk, you need to explore the family history over three generations.

The information that you collect depends on whether accurate information about the cancers that have occurred in the family is available. This information is often missing and sometimes inaccurate. Occasionally clinical geneticists and genetic counsellors can get further accurate information from death certificates or cancer registries.

You should include all first and second degree relatives. The family history should include unaffected relatives as well as relatives who have had cancer.

The key relatives are:

Parents,Siblings,Aunts and uncles,Grandparents

Children.

In certain circumstances, it may be important to gather information about first cousins and more distant relatives. For example, if a person's mother has breast cancer, and her mother has brothers only, it is useful to find out if any of the person's first cousins (the children of her mother's brothers) have had cancer.For each family member with cancer, it is important to know:

The specific type of cancer

The age at which cancer developed.

Learning bite: Unusual cancers

You should suspect that there may be a genetic predisposition to cancer in the family if any one of the following is present:Bilateral breast cancer or breast cancer in a man

Sarcoma in a patient under the age of 45

Glioma or childhood carcinoma of the adrenal cortex

Multiple family members who have had unusual cancers, such as sarcomas, at young ages - for example, this occurs in Li Fraumeni syndrome, caused by mutations in the tumour suppressor gene, p53.

Pitfalls in taking a family history of cancer

Many families have cancers on both the maternal and paternal sides of the familyYou must consider each side of the family separately - maternal and paternal side cancers are not additive

Some cancers, such as cancer of the ovary, endometrium, and prostate, are sex specific

You should be aware that both men and women can carry the genetic mutations that predispose to these cancers, and they can pass these genes on to their children

If a man carries a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2, for example, he will certainly never develop ovarian cancer and he is very unlikely to develop breast cancer. But if he has a daughter, she will have a one in two chance of inheriting his BRCA mutation

When there is an intervening man in a family with breast and/or ovarian cancer (for example, a man who has a sister and mother with breast cancer), you should count him as though he developed cancer

Most genetic mutations in the cancer genes are not 100% penetrant - that is, they increase the risk of cancer, but do not always cause it. This means that some people who are mutation carriers may live long healthy lives without ever developing cancer

Learning bite

Men who carry mutations in the BRCA2 gene have an increased risk of developing prostate cancer. The risk is highest under the age of 65. In men who develop prostate cancer under the age of 50 who have relatives with either breast or ovarian cancer, you should assess the family history to see whether there may be a familial risk of cancer

Factors in the family history suggestive of an increased risk of developing cancer

You can use the family history to look for clues which indicate a possible genetic predisposition to cancer.Important clues are:

Two or more closely related people who have the same type of cancer ,Closely related usually means first or second degree relatives. If there is an intervening man who is unaffected in a family with breast and/or ovarian cancer, you may also include more distant relatives, such as first cousins or great aunts and uncles.

In the family histor ,Unusual combinations of cancer within a family or in one individual, such as the combination of breast and ovarian cancer, or colorectal and endometrial cancer

The same type of cancer occurring in successive generations.

Cancer occurring at unusually young ages, such as colorectal or breast cancer under the age of 40.

Red flags to look out for

The presence of both breast and ovarian cancer in a family, or an individual who has both of these cancers, raises the possibility that a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation exists.The combination of colorectal cancer with cancer of the endometrium, ovary, or renal tract (particularly renal pelvis or cancer of the ureters) raises the possibility of Lynch syndrome (hereditary non polyposis colon cancer).

Cancers occurring in people under the age of 40 may suggest a genetic problem in the family. There is no absolute age which is a red flag for genetic cancer, but 40 is a useful guide.

Breast and ovarian cancer

What is the value of discovering that a person has an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer?Women who are at an increased risk of developing breast cancer because of their family history may benefit from interventions which have been shown to lead to early detection of breast cancer. They may also choose to have prophylactic surgery as a way of reducing their cancer risk (surgery is usually only offered to women who carry BRCA mutations).

For example, mammography can detect some breast cancers at an early stage, and this may lead to an improved prognosis. But there is currently no good evidence that breast screening reduces mortality from breast cancer in women with a family history of breast cancer and/or BRCA1/2 mutations

NICE (the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence) has published a guideline on familial breast cancer. This recommends annual mammography between the ages 40-49 for women with a family history that significantly increases their risk of developing breast cancer. Generally, women are considered to have a significantly increased risk if:

• One close relative under the age of 40

• Two close relatives (on the same side of the family) under the age of 50, or

• Three or more close relatives (on the same side of the family) of any age have breast cancer.

Clinical geneticists can offer women at particularly high risk, such as women who carry a mutation in one of the BRCA genes, intensive breast screening with both magnetic resonance imaging and mammography, earlier than the age of 40. Screening by magnetic resonance imaging for women at high risk of developing breast cancer is not yet widely available in the UK. It is expected to become more widely available in the future as it has now been recommended in the NICE Guidance.

Some carriers of a BRCA mutation choose to have prophylactic mastectomies in order to reduce their risk of developing breast cancer. The risk of breast cancer is reduced by up to 90%, depending on the type of surgery undertaken. Surgery is only suggested and not recommended to women who are known to carry a mutation. The decision whether to have a prophylactic mastectomy is ultimately down to patient choice.

Screening for ovarian cancer is of unproved value. NICE recommends that women at high risk should be offered ovarian screening only as part of research trials. Some women at high risk of ovarian cancer will choose to have prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomies. This involves total removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes. The fallopian tubes are removed because there is a risk of both ovarian and tubal cancer. Women must be given the information about the pros and cons of prophylactic surgery and it is their choice whether they decide to have surgery.

Prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy reduces the risk of ovarian and tubal cancer by up to 90%. If women have this surgery before their menopause, it has the added benefit of also reducing their risk of developing breast cancer.

Colorectal cancer

What is the value of discovering that an individual has an increased risk of colorectal cancer?With colorectal cancer, screening with regular colonoscopies has the potential to prevent cancer, by detecting and removing precancerous polyps.

Although there is no NICE guidance on the management of familial colorectal cancer, there are a number of widely used guidelines on the management of people at increased risk of colorectal cancer.

You should refer people at above-population risk to a gastroenterologist or colorectal surgeon, for screening colonoscopies. The age at which these colonoscopies start, and their frequency, depends on the level of risk and the family history. Those at highest risk may have annual or two yearly colonoscopies from the age of 25. Screening for those at lower risk is less intensive, ranging from five yearly colonoscopies, to a single screening colonoscopy at the age of 55.

Clinical geneticists may offer women from families with Lynch syndrome screening for endometrial cancer, but there are no agreed guidelines for this. If a woman from a family with Lynch syndrome requests screening for ovarian cancer because she is concerned, clinical geneticists should make her aware that screening for ovarian cancer is of unproved value, but they could enrol her in a local research study if she wishes.

It is recommended that people at very high risk of developing colorectal cancer, such as people who carry mutations in the familial adenomatous polyposis gene, should have prophylactic colectomies. In this highly penetrant condition, surgery is the only effective way of preventing cancer.

Learning bite: The NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme

For people who are not at increased risk of bowel cancer, the NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme, which will achieve nationwide coverage by 2009, will offer two yearly screening for bowel cancer to all men and women between the ages of 60 to 69. Cancer Research UK estimates that the programme could prevent about 1200 deaths every year in the UK from bowel cancer. The programme will be extended to men and women aged 70 to 75 from 2010, as set out in the Cancer Reform Strategy.How to manage a patient with an increased familial risk of breast cancer

Once you have taken a cancer family history and completed a family tree of at least three generations, you will need to assess what risk of developing cancer a patient has. This is so that you can decide whether you need to refer them for screening and/or specialist assessment. This can be complex. It is not easily done in the confines of a routine primary care consultation.You should reassure patients at near-population risk and manage them within primary care. You should offer to refer those at above population risk, for screening and/or specialist assessment, depending on what the local arrangements are.

To help you to identify women who qualify for mammograms before they reach the age of 50, here are a few rules of thumb, based on the NICE guideline.

You should offer a woman between the ages of 40-49 annual mammograms if:

She has a first degree relative (mother or a sister) who developed breast cancer younger than 40She has two or more affected relatives on the same side of the family

At least one first degree and one second degree relative diagnosed at any age or

Two first degree relatives diagnosed at any age.

NICE recommends that mammography for such patients should be offered in screening units that meet the same standards as the NHS Breast Screening Programme.

The NICE guidance also recommends seeking further advice for women who have a family history that includes:

Unusual cancers

A paternal family history of breast cancer

Jewish ancestry.

Once you have identified which patients you need to refer for screening and/or specialist assessment of the family history, you need to know where to refer them.

You should refer patients for screening either to a local hospital breast unit, or to the local NHS Breast Screening Service, depending on what your local arrangements are.

Please note that NHS Cancer Screening Programmes will take over the management of surveillance in 2009 and will not be taking direct referrals for surveillance from GPs. It is likely that they will take referrals from breast units, local familial breast cancer clinics (where these exist), or regional genetics centres.

You can obtain advice on where to obtain specialist assessment of family histories from regional genetics centres. Some regional genetics centres publish referral guidelines for breast, bowel, and ovarian cancer.

Some areas have specialist family history clinics. These clinics offer risk assessment services and referral to screening and, if necessary, specialist clinical genetics advice.

How to manage a patient with an increased familial risk of colorectal cancer

Because there is no NICE guidance on familial colorectal cancer, advice on how to assess and manage these patients is less uniform than that for breast cancer.Men and women who are at increased risk of bowel cancer because of their family history will benefit from being offered colonoscopic screening in addition to the NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme.

Local guidelines vary, but the following rules of thumb are useful in identifying family histories that could be significant. You should offer men and women referral for specialist assessment if they have:One or more first degree relatives diagnosed with colorectal cancer before the age of 45

Two or more first degree relatives (or one first and one second degree relative) diagnosed with colorectal cancer at any age.

You should offer people with family histories of colorectal cancer that also include endometrial, ovarian, or transitional cell cancers of the renal pelvis or ureter, specialist assessments in regional genetics centres.

If there is a known family history of Lynch syndrome or familial adenomatous polyposis, you should refer the patient directly to the regional genetics centre.

Depending on the outcome of the assessment, such patients may be referred for colonoscopy screening.

Once you have identified which patients may need screening and/or specialist assessment of the family history, you need to know where to refer them. In some areas, there are specialist colorectal family history clinics which will undertake specialist assessment of family histories and organise colonoscopy screening if appropriate. If no family history clinic exists, you should refer people who have significant colorectal cancer family histories either to a local hospital colorectal or gastroenterology unit (where a decision will be made about what screening is indicated) or to the cancer genetics service of your regional genetics centre.

Genetic tests

Tests for cancer genes are designed to look for specific mutations in genes which increase the risk of cancer. Clinical geneticists and genetic counsellors based in regional genetics centres carry out genetic testing of the cancer genes.Following an assessment at a clinical genetics department, clinical geneticists may offer families with substantial histories of breast and ovarian cancer testing of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes.For families who you suspect may have Lynch syndrome or familial adenomatous polyposis, testing may also be available.

The first step in the testing process is to identify the specific mutation that is responsible for cancers in the family. The initial genetic test is usually done on a family member who has or has had cancer. If there is no one with cancer in the family who is still alive, genetic testing may not be possible.

The initial test to search for a mutation in a family is expensive - often as much as £1000 - and time consuming. The results of these tests are sometimes difficult to interpret. A test to search for a mutation in a gene is similar to looking for a one letter spelling mistake in a long novel, without the benefit of a spell check programme.

If a specific mutation is identified in a family member who has cancer, other family members may request tests to see if they have inherited the causative mutation. Once a mutation is found in a family, the tests for other family members, known as predictive tests, are much cheaper and quicker, because the DNA laboratory knows what it is looking for.

Genetic tests and insurance

Patients are often concerned that a genetic test result will make it more difficult for them to obtain life insurance or health insurance. In the UK, the Department of Health and the Association of British Insurers have reached a voluntary agreement which ensures that the results of predictive genetic tests for cancer genes will not be taken into consideration in insurance applications. This agreement currently runs until 2014. Insurers normally ask applicants about their family histories of cancer, and this information may be used to determine what type of insurance is available.Attending to a patient's psychological needs

The first step in managing a patient's concern about their family history is to listen carefully to how they outline the problem. Giving the patient the time and space to express their concerns can be therapeutic in itself.The next vital step is to take a thorough family history. You can think of the family history as the equivalent of the history of the presenting complaint in a standard medical history.

Drawing a family tree together with the patient allows both the patient and the health professional to gain an objective view of the family history.

It is common for a patient to focus on a small number of relatives who have had cancer, while ignoring a large number of relatives who have lived long and healthy lives. The family tree is a visual way of getting the family history into perspective.

You may be able to offer genuine reassurance about a patient's risk of developing cancer once you have finished taking the family history. If you tell the patient that there's nothing to worry about without taking a thorough family history, the patient may be left with the feeling (with some justification) that you have not taken their concerns seriously.

Genetic counsellors, based in regional genetics centres, are experienced in helping patients to manage anxiety about their family histories.

Reducing cancer risk: lifestyle, diet, and exercise

Whatever a person's genetic risk of developing cancer, it is possible to reduce that risk by leading a healthy lifestyle.There is a body of evidence to show that the risk of developing cancer can be reduced by:

• Regular physical exercise

• A healthy diet

• Not smoking tobacco

• Avoiding excessive intake of alcohol

• Maintaining a normal body mass index.

Hormonal contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy may play a small role in increasing the risk of breast cancer. With regard to hormonal contraceptives, this risk needs to be balanced against the benefits of using these treatments (effective contraception and reduced risk of ovarian cancer). You need to assess each patient individually. A family history of breast cancer is not an absolute contraindication to the use of hormonal treatments. NICE recommends that:

You should give general health advice about hormonal contraception to women up to the age of 35 with a family history of breast cancer on the use of the oral contraceptive pill.

You should inform women aged over 35 with a family history of breast cancer that there is an increased risk of breast cancer associated with taking the oral contraceptive pill, given that the absolute risk increases with age.

What does the future hold?

Most of the predisposition genes for cancer that have high penetrance have now been identified. Testing for these genes is available for people who may carry mutations.For many families with a high incidence of breast, ovarian, and bowel cancer, these genes do not answer the question of why certain family members have an increased risk of cancer. The majority of family clustering of cancer is not explained by the genes that have so far been identified.

Current and future work is concentrating on identifying other genes with low penetrance which exert less powerful effects on predisposition to cancer. It is believed that these low penetrance genes may act together to cause cancer.

It may be possible to use this type of information as a way of identifying individuals or groups who would benefit most from earlier or more intensive mammographic screening or other measures that may be developed.

As with all rapidly developing fields, there may be some surprises as research continues.

Worked example 1

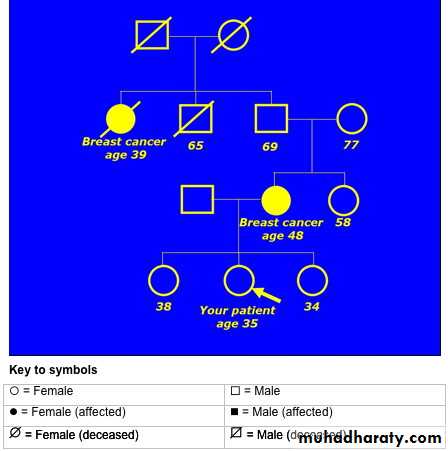

A 35 year old woman is concerned that there is a history of breast cancer in her family. Her mother developed breast cancer at the age of 48. She is also aware that her grandfather's sister died of breast cancer.The family pedigree drawing looks like this:

• What would you tell this patient about her genetic risk of developing breast or ovarian cancer?• This patient has two relatives on her maternal side of the family who developed breast cancer at quite young ages. The average age of diagnosis was 43.5 years (39 + 48, divided by 2).This indicates that her risk of developing breast cancer is significantly increased, because of genetic factors.

• This family history is complicated by the fact that the two women with breast cancer are separated by an intervening man - the patient's maternal grandfather.

• Remember that when there is an intervening man in a family with breast or ovarian cancer, you should count him as though he developed cancer.

You should offer to refer her to the local department of clinical genetics for further investigation and to discuss the possibility of genetic testing. The clinical geneticists may arrange annual mammography for this patient between the ages of 40-49, depending on the outcome of further investigations in the family.

• Worked example 2

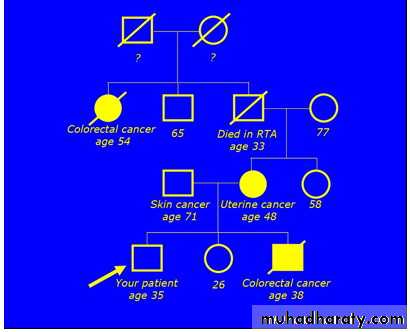

• A 35 year old man who is approaching the age at which his brother died from bowel cancer requests that you arrange a colonoscopy for him. He tells you that his brother died at the age of 38, within two weeks of being diagnosed with bowel cancer. He is also aware that other family members have had cancer.• This is his family tree:

•

Having constructed the family tree, what will you tell him?

This family has three cancers on the patient's maternal side. The combination of colorectal cancers at ages 38 and 54, together with cancer of the uterus at age 48, is suggestive of Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer).The fact that the patient's maternal grandfather died in a road traffic accident at the age of 33 makes the family tree more difficult to interpret. The skin cancer in the patient's father is not important, because it is the only cancer on the paternal side of the family.

You should offer to refer this patient to discuss the possibility of genetic testing. The genetics department may arrange colonoscopy screening of the patient (and his sister), depending on the outcome of further investigations in the family.

Having a first degree relative with breast cancer is not a contraindication to using the combined oral contraceptive. There is no evidence that the progestogen only pill carries a lower risk of breast cancer than the combined pill. Genetic tests are only offered when there is a significant chance of finding a mutation in a known gene. For most families, they are not the most reliable way of assessing the risk of developing cancer.

Cancers on both sides of the family are important. When assessing risk, you need to consider each side of the family separately. You must consider each side of the family separately - maternal and paternal side cancers are not additive.

Mutations in the high penetrance genes that predispose to cancers such as breast, ovarian, and colorectal cancers, are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. If one parent carries a mutation in one of these genes, there is a one in two risk of passing the mutation on each time they have a child. Autosomal recessive inheritance of mutated cancer genes is extremely rare. Autosomal recessive inheritance means that a child must inherit two faulty copies of a gene - one from each parent - in order to be affected by the condition caused by that gene.

None of the known cancer predisposition genes are on the X chromosome. These genes are carried by men and women equally. Some of the genes cause different manifestations in different sexes. Mutations in the BRCA genes, for example, cause a much higher risk of breast cancer in women than in men.

Breast cancers detected by screening tend to have a better prognosis than those detected clinically. Recent research shows that women whose breast cancers are detected by screening have a normal life expectancy. NICE recommends annual mammograms for women between the ages of 40-49 whose risk of breast cancer is significantly higher than average.

The standard NHS Breast Screening Programme begins at 50.

The risk of breast cancer based on family history is not significantly increased by one member family having breast cancer. But a first or second degree relative who has had breast cancer at a young age may be a sign of an increased familial risk. Mutations in the BRCA genes are relatively rare. Most families with two or more members with breast cancer will not have a mutation of the BRCA gene.

The prevalence of BRCA mutations is equal in men and women. Men who carry these mutations have a much lower risk of developing breast cancer than women.

Although the BRCA genes are associated with breast and ovarian cancer, the fact that there is no breast cancer in the family does not mean that there is not a familial risk of developing ovarian or breast cancer. Although a normal pelvic ultrasound might be reassuring, it has not been shown to be an effective screening tool for ovarian cancer. Ultrasound scanning of the ovaries produces both false positives and false negatives.

If the diagnoses of ovarian cancer are confirmed (a history of ovarian cancer may turn out to be uterine or cervical cancer), the patient or other members of the family may be offered genetic testing or entry into an ovarian screening research programme.

prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy is an effective way of preventing ovarian cancer.