Proposed Joint British Societies Cardiovascular Disease New Risk Assessment Charts 2009

د. حسين محمد جمعةاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2010

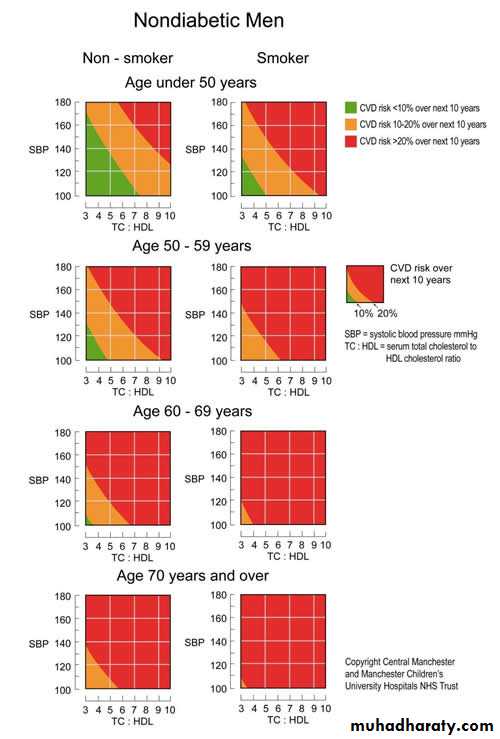

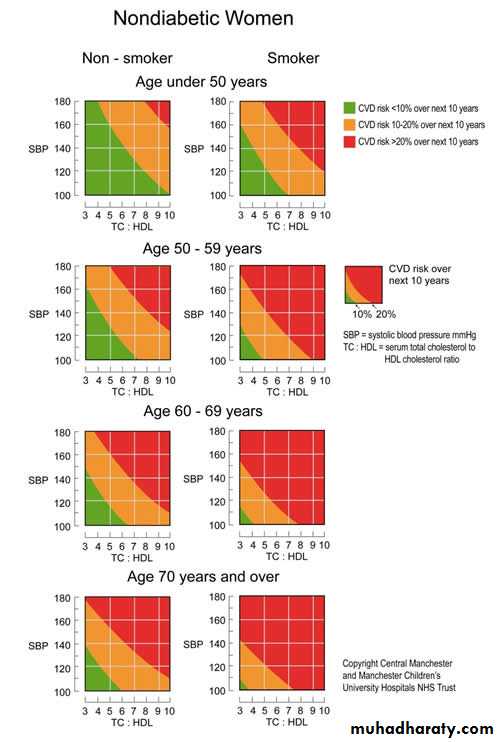

The recent NICE guidance on lipid management

[1] endorses the JBS2 recommendations [2] in advocating a cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk threshold of 20% over the next 10 years as an indication for the introduction of statin therapy. Both NICE and JBS2 also recommend that CVD risk is estimated using epidemiological data such as those generated from the Framingham Study as an aid to clinical judgment. They differ, however, in that NICE proposes that the upper age limit at which CVD risk is estimated in this way is extended to 75 years rather than the 70 years in JBS2. The figures below show new charts which are revised to permit this.The new charts also recognise that there is a small group of non-smoking men aged 50-59 years with low systolic and diastolic blood pressure and a low total serum cholesterol to HDL ratio whose CVD risk is less than 10% (green). This lack of recognition of their evident cardiovascular health in the earlier charts, although it would not lead to them receiving statin, might be discouraging to their maintenance of a healthy lifestyle. Furthermore, the distinction between 10% and 20% risk could become clinically more important if future statin indications become more liberal to take into account new clinical trial evidence.

It should also be noted that NICE lays more emphasis on an adverse family of CVD than JBS2. It recommends that, if early-onset CVD has occurred in a first degree relative (male aged less than 55 years or female aged less than 65yers) risk should be increased 1.5 times and that it should be doubled if more than one first degree relative has such a history.

How to use the Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction Charts for Primary PreventionThese charts are for estimating cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk (non-fatal myocardial infarction [MI] and stroke, coronary and stroke death and new angina pectoris) for individuals who have not already developed coronary heart disease (CHD) or other major atherosclerotic disease. They are an aid to making clinical decisions about how intensively to intervene on lifestyle and whether to use antihypertensive, lipid lowering medication and aspirin.

The use of these charts is not appropriate for the following patients groups. Those with: • CHD or other major atherosclerotic disease • Familial hypercholesterolaemia or other inherited dyslipidaemias • Chronic renal dysfunction • Type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus

How to use the Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction Charts for Primary PreventionThese charts are for estimating cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk (non-fatal myocardial infarction [MI] and stroke, coronary and stroke death and new angina pectoris) for individuals who have not already developed coronary heart disease (CHD) or other major atherosclerotic disease.

They are an aid to making clinical decisions about how intensively to intervene on lifestyle and whether to use antihypertensive, lipid lowering medication and aspirin.

The use of these charts is not appropriate for the following patients groups. Those with: • CHD or other major atherosclerotic disease • Familial hypercholesterolaemia or other inherited dyslipidaemias • Chronic renal dysfunction • Type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus

The charts should not be used to decide whether to introduce antihypertensive medication when blood pressure (BP) is persistently at or above 160/100 or when target organ damage (TOD) due to hypertension is present. In both cases antihypertensive medication is recommended regardless of CVD risk. Similarly the charts should not be used to decide whether to introduce lipid-lowering medication when the ratio of serum total to high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol exceeds 7. Such medication is generally then indicated regardless of estimated CVD risk.

To estimate an individual's absolute 10 year risk of developing CVD choose the table for his or her gender, smoking status (smoker/non-smoker) and age. Within this square define the level of risk according to the point where the coordinates for systolic blood pressure (SBP) and the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol meet. If no HDL cholesterol result is available, then assume this is 1.00mmol/l and the lipid scale can be used for total serum cholesterol alone.

Higher risk individuals (red areas) are defined as those whose 10 year CVD risk exceeds 20%.

The chart also assists in the identification of individuals whose 10 year CVD risk moderately increased in the range 10-20% (orange area) and those in whom risk is lower than 10% over 10 years (green area).

Smoking status should reflect lifetime exposure to tobacco and not simply tobacco use at the time of assessment. For example, those who have given up smoking within 5 years should be regarded as current smokers for the purposes of the charts.

The initial BP and the first random (non-fasting) total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol can be used to estimate an individual's risk.

Men and women do not reach the level of risk predicted by the charts for the three age bands until they reach the ages 49, 59, and 69 years respectively. The charts will overestimate current risk most in the under forties. Clinical judgement must be exercised in deciding on treatment in younger patients. However, it should be recognised that BP and cholesterol tend to rise most and HDL cholesterol to decline most in younger people already possessing adverse levels. Thus untreated, their risk at the age 49 years is likely to be higher than the projected risk shown on the age-less-than 50 years chart.

These charts (and all other currently available methods of CVD risk prediction) are based on groups of people with untreated levels of BP, total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol. In patients already receiving antihypertensive therapy in whom the decision is to be made about whether to introduce lipid-lowering medication or vice versa the charts can act as a guide, but unless recent pre-treatment risk factor values are available it is generally safest to assume that CVD risk is higher than that predicted by current levels of BP or lipids on treatment.

Those with a family history of premature CVD or stroke (male first degree relatives aged <55 years and female first degree relatives aged <65 years) which increases the risk by a factor of approximately 1.5

Those with raised triglyceride levels

Women with premature menopause

Those who are not yet diabetic, but have impaired fasting glucose (6.1-6.9mmol/l)

CVD risk is also higher than indicated in the charts for:-

In some ethnic minorities the risk charts underestimate CVD risk, because they have not been validated in these populations. For example, in people originating from the Indian subcontinent it is safest to assume that the CVD risk is higher than predicted from the charts (1.5 times)

The charts may be used to illustrate the direction of impact of risk factor intervention on estimated level of CVD risk. However, such estimates are crude and are not based on randomised trial evidence. Nevertheless, this approach maybe helpful in motivating appropriate intervention. The charts are primarily to assist in directing intervention to those who typically stand to benefit most.

Chronic heart failure:

a guide to managementin association with NICE

Heart failure is a complex clinical syndrome of symptoms and signs that suggest the efficiency of the heart as a pump is impaired. It is caused by structural or functional abnormalities of the heart. Some patients have heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction which is associated with a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Others have heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. The most common cause of heart failure in the UK is coronary artery disease, and many patients have had a myocardial infarction in the past.

Around 900 000 people in the UK have heart failure. Both the incidence and prevalence of heart failure increase steeply with age, with the average age at first diagnosis being 76 years. The prevalence of heart failure is expected to rise in future as a result of an ageing population, improved survival of people with ischaemic heart disease, and more effective treatments for heart failure.

Heart failure has a poor prognosis: 30-40% of patients diagnosed with heart failure die within a year - but thereafter the mortality is less than 10% per year. There is evidence of a trend of improved prognosis in the past 10 years. The six month mortality rate decreased from 26% in 1995 to 14% in 2005.

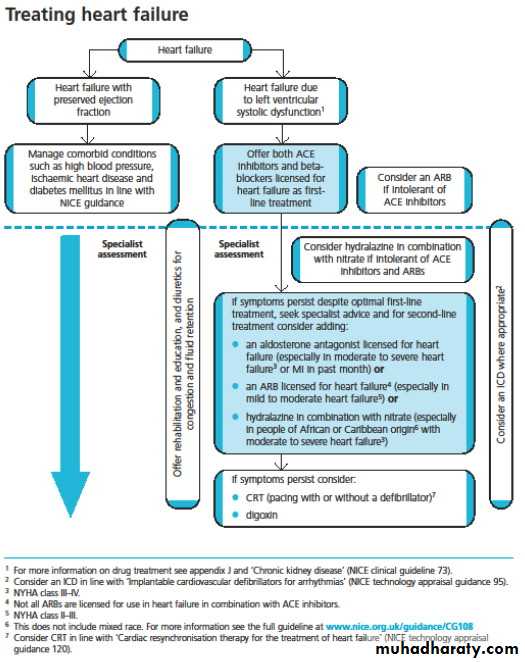

NICE published updated guidance on chronic heart failure recommending the use of both angiotension-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and beta-blockers in all patients with heart failure due to left ventricular dysfunction.

This should include older patients and those with peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, interstitial pulmonary disease, erectile dysfunction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) without reversibility.

We should not be depriving patients, and older patients in particular, with heart failure the use of beta-blockers.

“Lots of trials for mild to severe heart failure have shown that the drugs can achieve a significant reduction in mortality.

Start ACE inhibitor therapy at a low dose and titrate upwards at short intervals (for example, every two weeks) until the optimal tolerated or target dose is achieved. Measure serum urea, creatinine, electrolytes, and eGFR at initiation of an ACE inhibitor and after each dose increment. Patients whose uptitration of ACE inhibitors is completed ought to have their renal profile including their eGFR monitored every six months.

Patients should be strongly advised not to smoke. Patients with alcohol related heart failure should abstain from drinking alcohol. Healthcare professionals should be prepared to broach sensitive issues with patients, such as sexual activity, as these are unlikely to be raised by the patient. Patients need not abstain from sexual activity - it depends on their clinical condition.

Patients with heart failure should be offered an annual vaccination against influenza. Patients with heart failure should be offered vaccination against pneumococcal disease (only required once).

Air travel will be possible for the majority of patients with heart failure, depending on their clinical condition at the time of travel.

Clinical tip

Lifestyle measures are important regardless of the type or origins of the heart failure.

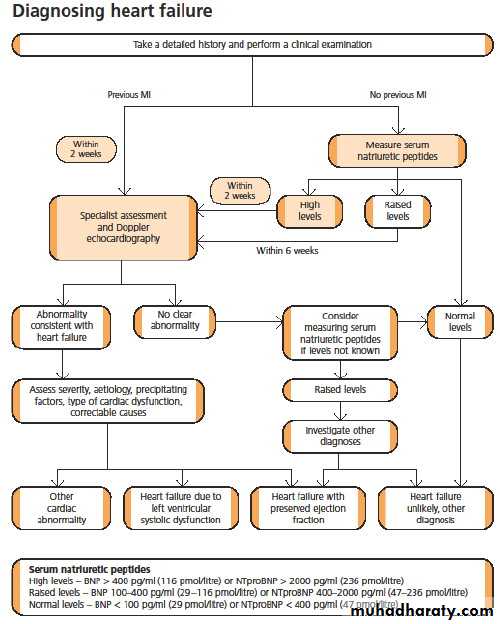

The updated guideline now recommends that GPs make a diagnosis of heart failure in patients suspected to have the condition who have not had a myocardial infarction by testing for elevated levels of natriuretic peptides rather than doing an electrocardiogram (ECG). This can either be by measuring B-type natriuretic peptides (BNP) or

N-terminal pro-B type natriuretic peptides (NTproBNP).

Refer patients with suspected heart failure and previous myocardial infarction (MI) urgently, to have transthoracic Doppler 2D echocardiography and specialist assessment within two weeks.

Consider alternative methods of imaging the heart (for example, radionuclide angiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, or transoesophageal Doppler 2D echocardiography) when a poor image is produced by transthoracic Doppler 2D echocardiography.

Because very high levels of serum natriuretic peptides carry a poor prognosis, refer patients with suspected heart failure and a BNP level above 400 pg/ml (116 pmol/l) or an NTproBNP level above 2000 pg/ml (236 pmol/l) urgently, to have transthoracic Doppler 2D echocardiography and specialist assessment within two weeks.

Refer patients with suspected heart failure and a BNP level between 100 and 400 pg/ml (29-116 pmol/l) or an NTproBNP level between 400 and 2000 pg/ml (47-236 pmol/l) to have transthoracic Doppler 2D echocardiography and specialist assessment within six weeks.

Learning bite

Be aware that:Obesity or treatment with diuretics, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta blockers, angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARBs), and aldosterone antagonists can reduce levels of serum natriuretic peptides

High levels of serum natriuretic peptides can have causes other than heart failure (for example, left ventricular hypertrophy, ischaemia, tachycardia, right ventricular overload, hypoxaemia (including pulmonary embolism), renal dysfunction (GFR <60 ml/minute), sepsis, COPD, diabetes, age >70 years, and cirrhosis of the liver).

Perform transthoracic Doppler 2D echocardiography to exclude important valve disease, assess the systolic (and diastolic) function of the (left) ventricle, and detect intracardiac shunts.

Seek specialist advice

Seek specialist advice and consider adding one of the following if a patient remains symptomatic despite optimal therapy with an ACE inhibitor and a beta blocker:An aldosterone antagonist licensed for heart failure (especially if the patient has moderate to severe heart failure (NYHA class III-IV) or has had an MI within the past month).

An angiotensin II receptor antagonist (ARB) licensed for heart failure (especially if the patient has mild to moderate heart failure (NYHA class II-III))

Members of the ARB class licensed for use in the UK include candesartan ,eprosartan ,irbesartan ,losartan ,olmesartan ,telmisartan ,and valsartan . Hydralazine in combination with nitrate (especially if the patient is of African or Caribbean origin and has moderate to severe heart failure (NYHA class III-IV)).

For patients who have had an acute MI and who have symptoms and/or signs of heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction, treatment with an aldosterone antagonist licensed for post-MI treatment should be initiated within 3-14 days of the MI, preferably after ACE inhibitor therapy.

Seek specialist advice and consider hydralazine in combination with nitrate for patients with heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction who are intolerant of ACE inhibitors and ARBs. Diuretics should be routinely used for the relief of congestive symptoms and fluid retention in patients with heart failure, and titrated (up and down) according to need following the initiation of subsequent heart failure therapies. Diuretics do not improve the patient's prognosis.

While you could add a loop diuretic or increase the dose of the loop diuretic if you detected signs of pulmonary or peripheral congestion; every attempt should be made to reduce the loop diuretic dose in order to facilitate the introduction of disease modifying therapy (which alters the prognosis). Diuretic therapy does not improve the patient's prognosis.

Learning bite

Offer both angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and beta blockers licensed for heart failure to all patients with heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Use clinical judgment when deciding which drug to start first.

The principles of pharmacological management of heart failure should be the same for men and women. The only exception to this can be in women of reproductive age. In such women who have heart failure, contraception and pregnancy should be discussed.

If pregnancy is being considered or occurs, specialist advice should be sought. Subsequently, specialist care should be shared between the cardiologist and obstetrician. The potential teratogenic effects of drugs should be considered.

Learning bite

Digoxin is recommended for:Worsening or severe heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction despite first and second line treatment for heart failure. The effect of digoxin on the heart rate is limited to the patient in the resting condition. However, in some patients with heart failure, adding digoxin may improve their exercise tolerance - especially if they are not in atrial fibrillation.

Amiodarone

The decision to prescribe amiodarone should be made in consultation with a specialistPatients taking amiodarone should have a routine six monthly clinical review, including liver function tests, thyroid function tests, pulmonary function tests, and a review of side effects

It is vital that the patient is informed at the time of commencing the beta blocker that transient pulmonary congestion may occur in the first few days after starting therapy. This responds well to increased doses of loop diuretics and is unlikely to need discontinuation of the beta blocker. The occurrence of this transient pulmonary congestion is not a bar against future uptitration of the beta blocker dose.

Coronary revascularisation should not be routinely considered in patients with heart failure due to systolic left ventricular impairment, unless they have refractory angina.

Clinical tip

Cough is common in patients with chronic heart failure, many of whom have smoking related lung disease. Cough is also a symptom of pulmonary oedema which should be excluded when a new or worsening cough develops.ACE inhibitor induced cough does not always require treatment discontinuation, however a troublesome dry cough which interferes with sleep and is likely to be caused by an ACE inhibitor should be acted upon.

All patients with chronic heart failure require monitoring. This monitoring should include:

A clinical assessment of functional capacity, fluid status, cardiac rhythm (minimum of examining the pulse), cognitive status, and nutritional status

A review of medication, including need for changes and possible side effects

Serum urea, electrolytes, creatinine, and eGFR.

The frequency of monitoring should depend on the clinical status and stability of the patient. The monitoring interval should be short (days to two weeks) if the clinical condition or medication has changed, but is required at least six monthly for stable patients with proved heart failure.

Patients who wish to be involved in monitoring of their condition should be provided with sufficient education and support from their healthcare professional to do this, with clear guidelines as to what to do in the event of deterioration (eg progressive rise in weight despite adherence to fluid restriction, or worsening of the symptoms of heart failure).

Routine monitoring of the chest x ray is not recommended.

Routine monitoring of the ECG is not recommended. However, should a patient display symptoms and/or signs of decompensation then the ECG ought to be repeated to assess the rhythm and to detect evidence of electrical dys-synchrony.Intravenous inotropic agents (such as dobutamine, milrinone, or enoximone) should only be considered for the short term treatment of acute decompensation of chronic heart failure. Specialist referral for transplantation should be considered in patients with severe refractory symptoms or refractory cardiogenic shock. Besides, it is unusual for a 70 year old patient to be accepted as a candidate for heart transplantation.

Routine monitoring of serum digoxin concentrations is not recommended.

A digoxin concentration measured within 8-12 hours of the last dose may be useful to confirm a clinical impression of toxicity or non-adherence.The serum digoxin concentration should be interpreted in the clinical context as toxicity may occur even when the concentration is within the therapeutic range.

Learning bite: end of life care

some patients will deteriorate despite optimal therapy. For such patients in whom medical treatment options are running out, you should consider palliative care. The palliative needs of patients and carers should be identified, assessed, and managed at the earliest opportunity. Patients with heart failure and their carers should have access to professionals with palliative care skills within the heart failure team. Issues of sudden death and living with uncertainty are pertinent to all patients with heart failure. The opportunity to discuss these issues should be available at all stages of care.Specialist palliative care day therapy

facilities offer assessment and reviewof need as well as a range of physical,

psychological and social care

interventions such as:

• Medical care including blood

transfusions and medication

adjustment.

• Nursing care, such as bathing and

dressing changes.

• Emotional and spiritual support.

• Social support.

• Services for families and carers.”

Diagnosis

Refer patients with suspected heart failure and previous myocardial infarction (MI) urgently, to have transthoracic Doppler 2D echocardiography and specialist assessment within two weeks.

Measure serum natriuretic peptides (B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NTproBNP)) in patients with suspected heart failure without previous MI.

Key points

Because very high levels of serum natriuretic peptides carry a poor prognosis, refer patients with suspected heart failure and a BNP level above 400 pg/ml (116 pmol/l) or an NTproBNP level above 2000 pg/ml (236 pmol/l) urgently, to have transthoracic Doppler 2D echocardiography and specialist assessment within two weeks.

Consider specialist monitoring of serum natriuretic peptides in some patients (for example, those in whom uptitration is problematic or those who have been admitted to hospital).

Treatment

In order to improve prognosis as well as symptoms, offer both angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and beta blockers licensed for heart failure to all patients with heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Use clinical judgment when deciding which drug to start first.Offer beta blockers licensed for heart failure to all patients with heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction, including:

Older adults and patients with:

Peripheral vascular disease

Erectile dysfunction

Diabetes mellitus

Interstitial pulmonary disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) without reversibility

Seek specialist advice and consider adding one of the following if a patient remains symptomatic despite optimal therapy with an ACE inhibitor and a beta blocker:

An aldosterone antagonist licensed for heart failure (especially if the patient has moderate to severe heart failure (NYHA class III-IV) or has had an MI within the past month)

An angiotensin II receptor antagonist (ARB) licensed for heart failure (especially if the patient has mild to moderate heart failure (NYHA class II-III))

Hydralazine in combination with nitrate (especially if the patient is of African or Caribbean origin and has moderate to severe heart failure (NYHA class III-IV)).

Digoxin is recommended for worsening or severe heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction despite first and second line treatment for heart failure.

Rehabilitation

Offer a supervised group exercise based rehabilitation programme designed for patients with heart failure.Ensure the patient is stable and does not have a condition or device that would preclude an exercise based rehabilitation programme

Include a psychological and educational component in the programme

The programme may be incorporated within an existing cardiac rehabilitation programme

Monitoring

All patients with chronic heart failure require monitoring, include:A clinical assessment of functional capacity, fluid status, cardiac rhythm (minimum of examining the pulse), cognitive status, and nutritional status

A review of medication, including need for changes and possible side effects

Serum urea, electrolytes, creatinine, and eGFR.

Referral for more specialist advice

Refer patients to the specialist multidisciplinary heart failure team for:• The initial diagnosis of heart failure

• The management of:

a.Severe heart failure (NYHA class IV)

b.Heart failure caused by valvular heart disease

c.Heart failure that does not respond to treatment

d.Heart failure that can no longer be managed effectively in the home setting.

Discharge planning

Patients with heart failure should generally be discharged from hospital only when their clinical condition is stable and the management plan is optimised. Timing of discharge should take into account patient and carer wishes, and the level of care and support that can be provided in the community. The primary care team, patient, and carer must be aware of the management plan. Clear instructions should be given as to how the patient/carer can access advice, particularly in the high risk period immediately following discharge.

A serum BNP level less than 100 pg/ml (29 pmol/l) or an NTproBNP level less than 400 pg/ml (47 pmol/l) in an untreated patient makes a diagnosis of heart failure unlikely .

The level of serum natriuretic peptide does not differentiate between heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction.

Learning bite

Consider a serum natriuretic peptide test (if not already performed) when heart failure is still suspected after transthoracic Doppler 2D echocardiography has shown a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction.Perform an ECG and consider the following tests to evaluate possible aggravating factors and/or alternative diagnoses:

Chest x ray

Blood tests:

Electrolytes, urea, and creatinine

eGFR (estimated glomerular filtration rate)

Thyroid function tests

Liver function tests

Fasting lipids

Fasting glucose

Full blood count

Urinalysis

Peak flow or spirometry.

Try to exclude other disorders that may present in a similar manner.

When a diagnosis of heart failure has been made, assess severity, aetiology, precipitating factors, type of cardiac dysfunction, and correctable causes.

Some beta-blockers (bisoprolol, carvedilol, nevibolol and extended-release metoprolol succinate [not licensed in the UK]) have been shown to be beneficial in people with heart failure compared to placebo. However, atenolol is widely used in the UK for other cardiovascular indications but is not licensed for use in heart failure

Beta-blockers

- Heart rate <60 bpm- Symptomatic hypotension- Greater than minimal evidence of fluid retention- Signs of peripheral hypoperfusion- PR interval >0.24 sec- Second- or third-degree atrioventricular block- History of asthma or reactive airways- Peripheral arterial disease with resting limb ischemia

Relative contraindications in patients with HF include:

Dosing —begun in very low doses and the dose doubled at regular intervals (eg, every two to three weeks) until the target dose is reached or symptoms become limiting . Initial and target doses are as follows:* For carvedilol, 3.125 mg twice daily with target dose of 25 to 50 mg twice daily (the higher dose being used in subjects over 85 kg)* For extended release metoprolol succinate, 12.5 or 25 mg daily with target dose of 200 mg/day* For bisoprolol, 1.25 mg once daily with target dose of 5 to 10 mg once daily.

The patient should weigh himself or herself daily and call the physician if there has been a

1 to 1.5 kg weight gain.

Weight gain alone may be treated with diuretics, but resistant edema or more severe decompensation may require beta blocker dose reduction or cessation (possibly transient).

Every effort should be made to achieve the target dose. The proportion of patients who reach the target dose is higher in clinical trials than in the general population in which the patients are older and have more comorbid disease. However, although not optimal, even low doses appear to be of benefit and should be used when higher doses are not tolerated.

During beta blocker initiation — Patients may have a period of worsening of HF symptoms lasting two weeks to two months after the initiation of beta blocker therapy.

This is minimized by starting at extremely low doses and titrating up every two weeks until target doses are reached.

Indications for beta blockers

HypertensionAngina

Mitral valve prolapse

Cardiac arrhythmia

Afibrillation

Heart failure

Myocardial infarction

Glaucoma

Migraine prophylaxis

Symptomatic control (tachycardia, tremor) in anxiety and hyperthyroidism

Essential tremor

Phaeochromocytoma, in conjunction with α-blocker

Beta blockers have also been used in the following conditions:

HOCM

Acute dissecting aortic aneurysm

Marfan(treatment with propranolol slows progression of aortic dilation and its complications)

Prevention of variceal bleeding in portal hypertension

Possible mitigation of hyperhidrosis

Social anxiety disorder and other anxiety disorders

ACE inhibitor therapy should generally be instituted before beta blocker therapy is initiated.

Data supporting initiation of beta blocker therapy first is limited.

A serum BNP level less than 100 pg/ml (29 pmol/l) or an NTproBNP level less than 400 pg/ml (47 pmol/l) in an untreated patient makes a diagnosis of heart failure unlikely.

The level of serum natriuretic peptide does not differentiate between heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction.

Treatment with diuretics, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta blockers, angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARBs), and aldosterone antagonists can reduce levels of serum natriuretic peptide.

learning bite

Consider a serum natriuretic peptide test (if not already performed) when heart failure is still suspected after transthoracic Doppler 2D echocardiography has shown a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction.Perform an ECG and consider the following tests to evaluate possible aggravating factors and/or alternative diagnoses:

Chest x ray

Blood tests:

Electrolytes, urea, and creatinine

eGFR (estimated glomerular filtration rate)

Thyroid function tests

Liver function tests

Fasting lipids

Fasting glucose

Full blood count

Urinalysis

Peak flow or spirometry.

Try to exclude other disorders that may present in a similar manner.

When a diagnosis of heart failure has been made, assess severity, aetiology, precipitating factors, type of cardiac dysfunction, and correctable causes.

Aspirin (75-150 mg once daily) should be prescribed for patients with the combination of heart failure and atherosclerotic arterial disease (including coronary heart disease).

However, even in patients with heart failure in sinus rhythm, anticoagulation should be considered for those with

• a history of thromboembolism,

• left ventricular aneurysm, or

• intracardiac thrombus.

Introduce beta blockers in a start low, go slow manner, and assess heart rate, blood pressure, and clinical status after each titration.

Switch stable patients who are already taking a beta blocker for a comorbidity (for example, angina or hypertension), and who develop heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction, to a beta blocker licensed for heart failure.

Start ACE inhibitor therapy at a low dose and titrate upwards at short intervals (for example, every two weeks) until the optimal tolerated or target dose is achieved. Measure serum urea, creatinine, electrolytes, and eGFR at initiation of an ACE inhibitor and after each dose increment. Patients whose uptitration of ACE inhibitors is completed ought to have their renal profile including their eGFR monitored every six months.

Offer beta blockers licensed for heart failure to all patients with heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction, including:

Older adults and patients with:

Peripheral vascular disease

Erectile dysfunction

Diabetes mellitus

Interstitial pulmonary disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) without reversibility.

Seek specialist advice and consider adding one of the following if a patient remains symptomatic despite optimal therapy with an ACE inhibitor and a beta blocker:

An aldosterone antagonist licensed for heart failure (especially if the patient has moderate to severe heart failure (NYHA class III-IV) or has had an MI within the past month)

An angiotensin II receptor antagonist (ARB) licensed for heart failure (especially if the patient has mild to moderate heart failure (NYHA class II-III))

Hydralazine in combination with nitrate (especially if the patient is of African or Caribbean origin and has moderate to severe heart failure (NYHA class III-IV)).

Amlodipine

should be considered for the treatment of comorbid hypertension and/or angina in patients with heart failure,

but verapamil, diltiazem, or short acting dihydropyridine agents such as nifedipine should be avoided.

Secondary prevention of ischaemic cardiac events

Secondary prevention of ischaemic cardiac eventsSecondary prevention is treatment to prevent recurrent cardiac morbidity and mortality and to improve quality of life in people who have established coronary artery disease and are at high risk of ischaemic cardiac events.

Incidence

Coronary artery disease is the leading cause of mortality in developed countries and is becoming a major cause of morbidity and mortality in developing countries. There are international, regional, and temporal differences in incidence, prevalence, and death rates. In the United States, the prevalence of coronary artery disease is over 6% and the annual incidence is over 0.33%.Aetiology

Most ischaemic cardiac events are associated with atheromatous plaques that can lead to acute obstruction of the coronary arteries. Coronary artery disease is more likely in people who are older or have risk factors, such as smoking, hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes mellitus.What are the effects of antithrombotic treatments?

AspirinAspirin reduced the risk of serious vascular events and reduced all cause mortality compared with placebo.

One of the reviews found that doses of 75 to 325 mg daily were as effective as higher doses (500 to 1500 mg).

low dose aspirin (<100 mg/day) was associated with a lower rate of bleeding than that seen with higher doses of aspirin.

Comments

Among people at high risk of cardiac events, the absolute reductions in serious vascular events associated with aspirin far outweigh any absolute risks.

Systematic reviews have found strong evidence that beta blockers reduce the risk of all cause mortality, coronary mortality, recurrent non-fatal myocardial infarction, and sudden death in people after myocardial infarction.

One systematic review found no differences in effect between men and women. In patients with heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction, beta blockers reduced mortality compared with placebo, and the relative benefit was not significantly different between people with and without diabetes.

Although fish oil capsules may confer some protection after a myocardial infarction, there is no evidence to support taking them instead of a statin.

the prevalence of coronary artery disease is over 6%, and the annual incidence is over 0.33%.

What are the effects of other drug treatments?

Beta blockersBeta blockers reduce the risk of all cause mortality, coronary mortality, recurrent non-fatal myocardial infarction, and sudden death in people after myocardial infarction. One systematic review found no differences in effect between men and women. In patients with heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction, beta blockers reduced mortality compared with placebo, and the relative benefit was not significantly different between people with and without diabetes.

Harms

One systematic review that examined the harms of beta blockers compared with placebo in people with previous myocardial infarction, heart failure, or hypertension found no significant difference between beta blockers and placebo in reported symptoms of depression or sexual dysfunction. However, it found a small but significant increase in fatigue with beta blockers compared to placebo..Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (in people with and without left ventricular dysfunction)

(ACE) inhibitors reduced the risk of serious cardiac events in stable people without left ventricular dysfunction or heart failure who were at high risk of cardiovascular events. Two systematic reviews found that ACE inhibitors reduced mortality in people with heart failure and/or left ventricular dysfunction, including patients with a recent myocardial infarction. One systematic review found a smaller benefit in women, but equal benefit in people with and without diabetes and in black and white people.

Harms

A systematic review reported adverse effects from three of five trials included in the review. Hypotension, renal dysfunction, and cough occurred more frequently with ACE inhibitors than with placebo. Hyperkalaemia also occurred more commonly in patients treated with ACE inhibitors.Angiotensin II receptor blockers

In patients with stable coronary artery disease without left ventricular dysfunction, there is less evidence for secondary prevention with an angiotensin II receptor antagonist than there is for ACE inhibitors. However, one randomised controlled trial which recruited 406 patients found a reduction in the composite end point of cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and revascularisation with the use of low dose candesartan, compared with usual care, in people with a past history of coronary intervention and no significant coronary stenosis on follow up coronary angiography six months after intervention, most of whom were not taking ACE inhibitors.However, a more recent randomised controlled trial recruited 25 620 patients with coronary, cerebrovascular, or peripheral arterial disease or diabetes with end organ damage, and without heart failure. Patients were randomised to telmisartan 80 mg daily (8542 patients), ramipril 10 mg daily (8576 patients), or the combination (8502 patients). There was no significant difference in the primary outcome of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, or hospitalisation for heart failure during a median follow up of 56 months between the three groups.

In view of the more recent evidence patients with stable coronary artery disease without heart failure and who are intolerant of ACE inhibitors, should be considered for an angiotension II receptor antagonist.

Harms

The randomised controlled trial of candesartan did not report adverse effects. However, 4% of participants were reported to be intolerant of candesartan. In the larger randomised controlled trial, the incidence of cough (4.2% versus 1.1%) and angio-oedema (0.3% versus 0.1%) was higher with ramipril compared to telmisartan, but hypotensive symptoms occurred less frequently (1.7% versus 2.6%).Angiotensin II receptor blockers added to ACE inhibitors

No systematic reviews were found. The randomised controlled trial of patients with coronary, cerebrovascular, or peripheral arterial disease or diabetes with end organ damage, and without heart failure which randomised patients to treatment with ramipril v telmisartan v the combination found no significant difference in the primary outcome of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, or hospitalisation for heart failure during a median follow up of 56 months with the combination of telmisartan and ramipril compared to either drug alone.Calcium channel blockers

One systematic review found no significant difference in mortality between calcium channel blockers and placebo in people after myocardial infarction. However, subgroup analysis by drug type found that diltiazem and verapamil reduced rates of refractory angina in people without heart failure after myocardial infarction.Harms

Three randomised controlled trials of either diltiazem or verapamil compared with placebo found a trend towards harm for people with clinical manifestations of heart failure.

Class I antiarrhythmic agents (quinidine, procainamide, disopyramide, encainide, flecainide, and moracizine)

One systematic review found that taking class I antiarrhythmic agents after myocardial infarction increased the risk of cardiovascular mortality and sudden death compared with placebo. One randomised controlled trial found that, in people who have had a myocardial infarction with ventricular ectopy which could be suppressed with flecainide, encainide, or moracizine, treatment with either flecainide or encainide compared to placebo increased the risk of cardiac arrest and death.

Harms

The systematic review compared the effects of class I antiarrhythmic drugs versus placebo on mortality. The review found that antiarrhythmic agents increased mortality compared with placebo.The additional randomised controlled trial found that either encainide or flecainide compared with placebo increased the risk of cardiac arrest and death after 10 months.

Comments

The evidence shows that class I antiarrhythmic drugs should not be used in people after a myocardial infarction.

Amiodarone

Two systematic reviews found that amiodarone (a class III antiarrhythmic agent) significantly reduced the risk of all cause mortality and arrhythmic/sudden death, compared with placebo, in people with a recent myocardial infarction and a high risk of death from cardiac arrhythmia (including left ventricular dysfunction).

In one of the largest randomised controlled trials, there was no significant difference in all cause mortality (the primary outcome) or cardiac mortality, although there was a favourable interaction between the use of beta blockers and cardiac mortality. There was also a favourable interaction in a second randomised controlled trial between the use of beta blockers and the primary outcome of resuscitated ventricular fibrillation or arrhythmic death.

Harms

Adverse events leading to the discontinuation of amiodarone are hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, peripheral neuropathy, lung infiltrates, bradycardia, and liver dysfunction.Comments

More recent trials have examined the efficacy of implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD). An ICD should be considered in patients with a past history of myocardial infarction who are at high risk of arrhythmic death and who fulfil prespecified criteria, rather than treatment with amiodarone.

Hormone replacement therapy

One randomised controlled trial found no overall significant difference between conjugated equine oestrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate and placebo in cardiac events among postmenopausal women with coronary artery disease after 4.1 years of follow up, although there was a pattern of an increased risk in coronary events in year 1, with fewer in years 4 and 5. Extension of the trial with open label treatment found that there remained no significant difference between the two groups.An additional randomised controlled trial in women with angiographically proved ischaemic heart disease also found no significant difference with transdermal 17 beta oestradiol, with or without a cyclical progestogen, compared to placebo on coronary events. Furthermore, a third trial found no significant difference between oestradiol valerate and placebo on reinfarction, cardiac death, and all cause mortality in women after myocardial infarction.39

Harms

• Combined oestrogen and progestogens versus placeboOne randomised controlled trial, with extended open label follow up, found an increase in the incidence of biliary tract surgery and of any venous thromboembolic event in women allocated to hormone replacement therapy, compared to placebo.

2. Oestrogen alone versus placebo

In one randomised controlled trial, 208 out of 373 women treated with oestradiol valerate, who had not had a hysterectomy, had vaginal bleeding during 24 months of treatment. There was no significant difference in venous thromboembolic events, stroke, transient ischaemic attack, breast cancer, endometrial cancer, or fracture in those treated with oestrogen compared to placebo, although the study may have been underpowered to detect these.What are the effects of cholesterol reduction?

Statins

A meta-analysis of 14 trials, including both primary and secondary prevention populations, found that statins compared to placebo reduce all cause mortality and major vascular events, with no adverse effect on non-vascular mortality. The relative risk reduction was similar in those with and without previous vascular disease, in those with and without diabetes, in those who were older or younger than 65 years of age, and in both men and women.

Harms

In two cohort studies, and supported by data from 20 randomised trials, the incidence of rhabdomyolysis was 3.4 per 100 000 person years in patients treated with statins, and the incidence of myopathy was 11 per 100 000 person years. Elevation in liver enzymes is more common with statin treatment than with placebo, but the incidence of clinical liver disease is rare, with an estimated rate of liver failure of about 0.5 per 100 000 person years. Evidence from cohort studies and case reports estimates a small risk of peripheral neuropathy in people treated with statins of 12 per 100 000 person years.Comments

People in the large statin trials in both treatment and placebo groups were also given dietary advice aimed at lowering cholesterol.A systematic review has examined the efficacy of any cholesterol lowering intervention on mortality, and in a meta-regression analysis, found that variability across trials was largely explained on the basis of differences in the amount by which cholesterol was reduced. This is consistent with the meta-analysis of combined primary prevention and secondary prevention trials, in which relative risk reduction was greater, with greater reductions in low density lipoprotein cholesterol,41 and the absolute reduction in risk is dependent on the baseline risk of an ischaemic event in the population being treated.

What are the effects of non-drug treatments?

Antioxidant vitamin combinationsThree randomised controlled trials included in a systematic review found no benefit of antioxidant combinations on cardiovascular events or cardiac mortality.

Beta carotene

A systematic review found no reduction in cardiovascular risk from beta carotene supplementation. In a more recent randomised controlled trial of women aged 40 years or more with a prior cardiovascular event or three or more cardiovascular risk factors, treatment with beta carotene had no effect on the composite of cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, or revascularisation.

Vitamin C

Evidence is limited on its efficacy. In a randomised controlled trial of women aged 40 years or more with a prior cardiovascular event or three or more cardiovascular risk factors, treatment with vitamin C had no effect on the composite of cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, or revascularisation.Vitamin E

Two systematic reviews found inconclusive evidence about the benefits of vitamin E. In a pooled analysis there was no beneficial or adverse effect.48 In a randomised controlled trial of women aged 40 years or more with a prior cardiovascular event or three or more cardiovascular risk factors, treatment with vitamin E had no effect on the composite of cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, or revascularisation.

Harms

The secondary prevention randomised controlled trials reported no consistent harms with vitamin supplementation, although in 1 in 1862 male smokers with a past history of myocardial infarction, beta carotene was associated with an increase in fatal coronary heart disease and fatal myocardial infarction. However, there was no effect on total coronary events and myocardial infarctions. This was a subgroup of a larger randomised controlled trial of 29 133 male smokers which examined the efficacy of daily supplementation with alpha-tocopherol or beta carotene, or both, compared to placebo in reducing the incidence of lung cancer or other cancers. It found evidence of an increase in lung cancer incidence and lung cancer mortality with beta carotene supplementation.

Cardiac rehabilitation including exercise

Two systematic reviews found that, compared with usual care, cardiac rehabilitation reduced mortality, and one found a reduction in recurrent myocardial infarction. The first review also reported a beneficial impact on modifiable risk factors, with reductions in total cholesterol, triglycerides, systolic blood pressure, and lower rates of self reported smoking with cardiac rehabilitation compared to usual care.Health related quality of life was assessed using a variety of outcome measures. Some of the trials included in the systematic reviews reported an improvement with cardiac rehabilitation compared to usual care, but effect sizes were generally small.

Harms

Rates of adverse cardiovascular outcomes (syncope, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, or sudden death) were low in supervised rehabilitation programmes.Diet

Mediterranean dietOne randomised controlled trial found that advising people after a first myocardial infarction to eat a Mediterranean diet (more fruit and vegetables, bread, pasta, potatoes, olive oil, and rapeseed margarine), compared to a Western diet, led to a reduction in all cause and cardiovascular mortality, and the combination of recurrent myocardial infarction and cardiac death.

Advice to eat less fat

We found no strong evidence from randomised controlled trials on the effects of advising people to eat a low fat diet.

Advice to eat more fibre

There was no evidence from one randomised controlled trial, included in a systematic review, that a high fibre diet has any effect on cardiac or all cause mortality.

Fish oil consumption (from oily fish or capsules)

Two of three randomised controlled trials, both involving people with a recent myocardial infarction, found a protective effect of increasing fish intake or taking a fish oil supplement, and two cohort studies were consistent with this. In the third randomised controlled trial of men with angina, those advised to eat oily fish, and in particular those supplied with fish oil capsules, had a higher risk of cardiac death.Harms

No major adverse effects of dietary advice have been reported, but very high doses of fish oil may increase the risk of bleeding.

Smoking cessation

No randomised controlled trials of the effects of smoking cessation on cardiovascular events in people with coronary heart disease were found. Observational studies have found that smoking cessation significantly reduces the risk of myocardial infarction and death in people with coronary heart disease.

Harms

Two randomised controlled trials found no evidence that nicotine replacement, using transdermal patches, in people with stable coronary heart disease increases cardiovascular events.

Prognosis

Within one year of having a first myocardial infarction, it has been reported that 25% of men and 38% of women will die.Within six years of having a first myocardial infarction, 18% of men and 35% of women will have another myocardial infarction, 22% of men and 46% of women will have heart failure, and 7% of men and 6% of women will have sudden death.

The patient's outcome after acute myocardial infarction has improved over recent years. Between 1999 and 2006, in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction there was a fall in in-hospital deaths, congestive heart failure, and pulmonary oedema, and a fall in myocardial infarction diagnosed more than 24 hours after presentation to hospital or recurrent myocardial infarction. Between hospital discharge and a time frame of six months, there was a reduction in the rate of myocardial infarction and stroke.

In patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome, there was also a reduction in in-hospital deaths, congestive heart failure, and pulmonary oedema, and myocardial infarction diagnosed more than 24 hours or recurrent myocardial infarction. Between hospital discharge and a time frame of six months, there was a reduction in the rate of death and stroke. In both groups, there was an increase in evidence based interventions during the time period.

Aspirin and clopidogrel

Aspirin and clopidogrel together are more effective than aspirin alone, and should be started at the time that the myocardial infarction occurs.A randomised controlled trial found that, in people with acute non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome, clopidogrel taken in combination with aspirin, compared to aspirin alone, reduced serious cardiovascular events, with a mean duration of nine months. Two further randomised trials found that, in people with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction, clopidogrel in addition to other standard treatment, including aspirin, reduced adverse cardiac events compared to treatment with placebo. Maximum follow up was 30 days, and people treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention were excluded.

Low dose warfarin

No evidence was found which examined the efficacy of low dose warfarin alone in patients with myocardial infarction, and adding fixed, low dose warfarin to aspirin had no effect on cardiovascular outcomes compared to aspirin alone. A systematic review found that, when added to aspirin, moderate or high intensity oral anticoagulation reduced the risk of serious cardiovascular events compared with aspirin alone, but increased the risk of major haemorrhage.Stop taking the aspirin immediately

Prolonged treatment with an antiplatelet drug such as aspirin reduces the risk of serious vascular events in people at high risk of ischaemic cardiac events, compared with placebo or no treatment.If patient developed dyspepsia, this would need to be investigated appropriately, but it is preferable to give a combination of aspirin and a proton inhibitor, rather than to change aspirin to an alternative antiplatelet agent such as clopidogrel. (In patients with aspirin induced ulcer bleeding whose ulcers had healed before study treatment, the combination of aspirin and esomeprazole was more effective than clopidogrel in the prevention of recurrent ulcer bleeding.)

Learning bite: the right ventricle

There are a number of anatomical and physiological properties of the right ventricle that differentiate it from the left ventricle:

The right ventricle has only 15% of the muscle mass of the left ventricle, but has the same cardiac output. This reflects its role in perfusion of the low pressure pulmonary circulation

Coronary perfusion of the right ventricle occurs biphasically in both systole and diastole. Coronary perfusion of the left ventricle only occurs in diastole

The right ventricle has a lower coronary resistance than the left ventricle, with a tendency for left to right collateral vessel formation.

These differences allow the right ventricle to have a lower oxygen demand and better oxygen delivery, so it is more resilient to ischaemia than the left ventricle.