Deliberate self harm

د. حسين محمد جمعةاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2010

What is deliberate self harm?

Deliberate self harm is an act by a person with the intent of harming themself physically. Deliberate self harm is frequently referred to as attempted suicide or parasuicide, particularly when the patient's intention was to die. Yet not all patients want to die and self destructive behaviour often results when a person's sense of desperation outweighs their inherent instinct for self preservation.9 A greater proportion of people have suicidal thoughts than suicidal actions. Using data from the US National Comorbidity Survey, Borges et al found that 13.3% reported lifetime suicidal ideation, 4.0% reported a lifetime suicide plan, and 2.2% reported a suicide attempt.The most common form of self harm is intentional self poisoning (overdose), accounting for 80% of self harm incidents. Some 10% involve self laceration and a further 10% involve less common methods.

Paracetamol is the most common type of overdose and is particularly common in people who self harm for the first time and in young people (antidepressants and sedative overdoses are more common in people who self harm repeatedly and older people). Self poisoning with gas and non-ingestible poisons is associated with high suicidal intent

Why do patients harm themselves?

Reasons for self harm are complex and overlapping.12 Studies show that about half of people who self harm say they intended to die, and about half wanted to escape from an intolerable situation or intolerable state of mind.12 A minority can offer no clear explanation.13It is almost always a mistake to label a person presenting distressed as "attention seeking" to justify withholding professional help. Without help up to 50% of patients will repeat the act, including 25% in the first year alone. Up to 20% will attend an accident and emergency department more than three times a year on average and these "multiple attenders" will need a disproportionate amount of clinical time (and ultimately NHS costs).

The median mortality from suicide after deliberate self harm is:

Nearly 2% within the first year7% in the first 10 years

About 15% thereafter.

This is sometimes approximated to 1% per year; or a 100-fold relative risk.

One way to try to understand the causes underlying deliberate self harm is simply to ask people why they presented in this way; it is surprising how rarely doctors do this adequately. Reasons people give for deliberate self harm are diverse, but most commonly involve interpersonal difficulties (Table 1). There is also a strong trend for people who self harm to show traits of impulsiveness and impaired problem solving.

Table 1. Reasons given by patients for deliberate self harm

Difficulties with partner

64%Family stresses

60%

Financial problems

59%

Problems at work

48%

Mental health

46%

Issues with friends

40%

Housing difficulties

40%

Alcohol problems

32%

Issues with physical health

32%

Bereavement

29%

Isolation

18%

Problems with illicit drugs

14%

Risk factors for self harm

There is no single proved risk factor that has an adequate predictive value when used alone. For example, we know that deliberate self harm is more likely in women, young adults, people who are single or divorced, and people with a low education level. However, these factors are also common in people who do not deliberately self harm repeatedly. One of the strongest risk factors - history of a previous deliberate self harm attempt - has a modest sensitivity and specificity of about 60%.

One way round this is to concentrate on risk factors that need an intervention immediately regardless of uncertain future consequences (for example, depression). It is also possible that using a combination of risk factors together might have a predictive value; this is the premise underlying risk assessment tools.

There are many risk assessment tools, but few have been evaluated scientifically as predictors of repeat self harm. Of the handful that have been tested (for example, the Edinburgh Risk of Repetition Scale) some people who would not have harmed themselves are inevitably misidentified as high risk, and some people who do come to harm are not identified.22 Routine clinical "risk assessment" correctly identifies only about one in four cases who are flagged as having a high risk but about nine out of 10 thought to have low risk.23 Clinicians (using a simple four item questionnaire) had about 5% greater accuracy than those not using a tool in one study.24 That said, a tool can act as a useful prompt for history taking. In addition several common depression scales (such as the Beck Depression Inventory, and the Patient Health Questionnaire) feature a question on suicidal thoughts.

Repeat deliberate self harm and suicide share most risk demographic factors including being single, unemployed, and without good social ties, yet suicide after deliberate self harm is even more difficult to predict.

The possibility of an untreated psychiatric disorder such as depression, anxiety disorder, substance misuse, and, less commonly, psychosis is of paramount importance. All patients should be assessed for these conditions, ideally by an experienced member of staff. In contrast to predictive risk assessment tools, diagnostic screening instruments have been thoroughly tested and may augment a clinical diagnosis and quantify severity, but at the expense of time and training.

Management

Mental health assessmentAs a junior doctor in accident and emergency you will certainly be asked to attend to the medical needs of patients who have self harmed, but you will also need to carry out an initial mental health assessment (Tables 2 and 3). This is sometimes thought of as a screening interview, and is important because it identifies all cases of possible concern and is often the first contact that patients have.

Unfortunately there is little privacy, or security, despite clear guidelines to the contrary. The key question to ask when assessing the mental state of someone after deliberate self harm is: are there sufficient concerns about future harm to the patient (or others) or about symptoms of mental ill health to warrant further help?

Table 2. Stages in a deliberate self harm assessment

Arrange to see the patient safely and in a suitable room, respecting privacyClarify that the patient is alert enough to benefit from an assessment

Introduce yourself and explain the assessment process

Allow the patient to give their account of what has happened

Gently ask about possible causes, and future intentions

(see 10 steps in Table 3)

Find out if there are unmet physical or psychosocial needs and if the person wants further help

If unsure, ask for assistance from an experienced colleague

If appropriate arrange for follow up with an agency that best suits the patient (this must be agreed with the patient if they are expected to attend).

Table 3. Practical steps in a psychosocial assessment

These questions form 10 essential steps of a psychosocial assessment. You can add further questions as needed.

What are the patient's demographic details?

What was the deliberate self harm event?

What medical treatment (if any) was needed?

What were the recent stresses and social circumstances?

What were the relevant background social factors?

Are there any psychiatric symptoms or signs?

How would you describe the patient now?

What is the patient's view of the future?

Do they have ongoing thoughts, plans, or intent regarding self harm or suicide?

Where is the patient going to go now?

Treatments

The Royal College of Psychiatrists and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence did not recommend a definitive intervention for deliberate self harm in their guidelines. This was not for lack of looking because there have been more than 20 randomised controlled trials in adults and 10 in adolescents. Until recently few produced convincing results, mainly because of inadequate sample size. Only a large sample size allows inspection of suicide (rather than repeat self harm) as an outcome. The following interventions have recently been summarised in JAMA.Antidepressants

Three small randomised controlled trials of paroxetine, mianserin, and flupentixol depot hint at a possible beneficial effect, but it is currently difficult to fund the necessary large scale studies of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Antidepressants have a proved role when depression or anxiety is detected, but they are unlikely to have a role when mood disorder has been carefully excluded.Problem solving therapy

Five randomised controlled trials (involving 571 people) found no significant difference between problem solving therapy and usual care in the number of people who repeated deliberate self harm. But there was a reduction in depression, anxiety, and hopelessness, which suggests a benefit.Priority future treatment (emergency card)

Two studies found no significant reduction in the number of people who repeated deliberate self harm between people given an emergency card (which allowed emergency admission or contact with a doctor when they first came to the accident and emergency department) and usual care. In fact there was a small deleterious effect in repeat attenders in the emergency card group).

Further contact after discharge

Several independent studies found that follow up of patients initially seen for deliberate self harm reduces the subsequent repeat rate.36 Intriguingly, follow up may be successful by telephone or letter, although these need to be compared with face to face contact.After many unpowered trials, finally in 2008 WHO funded a large multicentre trial of brief information and nine follow up contacts up to 18 months. Significantly fewer deaths from suicide occurred in the active treatment group (0.2% versus 2.2%).

When to refer to a specialist service

Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence suggest that as well as having a preliminary psychosocial assessment at triage by staff in the accident and emergency department, all people who have self harmed should be offered a full mental health and social needs assessment by a mental health professional. In reality, few services are organised to do this and so the benefit of this system has not yet been demonstrated.The Royal College of Psychiatrists suggests that there should be a clear policy for referral for specialist assessment of patients admitted to general medical wards and that the patient should be seen within 24 hours. It also suggests that you should make a referral for self harm assessment when the patient is fully conscious and able to complete a psychosocial assessment, but the patient need not be medically fit for discharge at the time.

The following criteria may merit a specialist referral (and possible hospital admission)

A clear continuing intent to self harm again or a wish to die from suicideClinical features of mental health problems needing further help

Problems with consent to treatment due to mental health problems

Problems with alcohol/drug dependency and a sincere wish for further help

Behavioural disturbance that may be due to mental health problems.

Conclusion

Junior doctors are in the front line for managing people who deliberately self harm and for preventing suicide. In some centres junior doctors see most of the patients who deliberately self harm, yet they are often relatively untrained and unsupported. Each trust should develop and implement a local guideline on training and supporting junior doctors. This is especially pertinent given the Department of Health's guidelines on four hour transit times through accident and emergency departments.Brief intervention and follow up contact are now the preferred treatment following self harm. Clinicians may provide a flexible response depending on the needs of individual patients. These packages are already leading the way in the treatment of late life depression with or without suicidal thoughts.

Reflect

How to reflect

Reflecting isn't just about closing your eyes and having a think. To really reflect you should ask yourself these questions:

What do I think this learning module was about?

Can I apply it in my work?

What barriers am I likely to come across?

How will I manage these barriers?

How will I know if I'm doing things better?

To help consolidate your learning from this module, work through these questions and answer

Should I use a formal risk assessment tool?

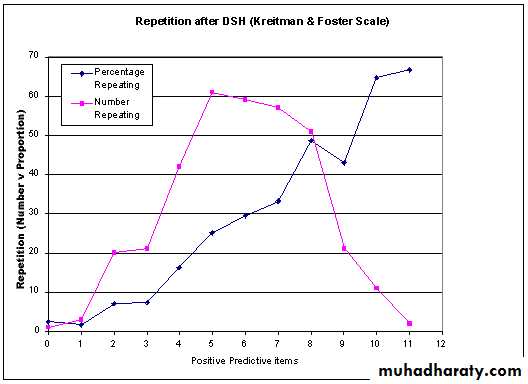

This is controversial. Krietman and Foster designed the Edinburgh Risk of Repetition Scale to predict repetition of deliberate self harm. They discovered that patients who scored in the middle range of the deliberate self harm scale (3-9 items) accounted for the majority of repeaters (Figure). This is because there are relatively few high scoring individuals. Although these patients carry a high relative risk, their total number (absolute risk) is low.• Repetition after deliberate self harm (Kreitman and Foster scale).

•Repetition after deliberate self harm (Kreitman and Foster scale).

In contrast, a far greater number carry an intermediate risk. This has recently been replicated in a comparison of risk assessments by accident and emergency staff and by psychiatrists. From a population perspective, therefore, prevention is more effective when targeting large numbers at low or moderate risk.41 42 From an individual perspective, services with limited resources sensibly target highest risk groups first, and gradually try to expand.Because no tool is perfect, you also need to consider their positive and negative predictive value. Because the baseline prevalence rate of repeat deliberate self harm (and suicide even more so) is rare, scales will perform better statistically at ruling out cases of possible concern than confirming definite cases.

The short answer is that established scales may act as a useful clinical prompt for less experienced members of staff and when judging whether to make a more specialist referral.

What should I do if someone refuses treatment?

This area causes most uncertainty for staff. All staff have a duty of care to their patients and must always attempt to act in a person's best interest. If a patient cannot consent (whether for medical or psychiatric reasons) treatment must go ahead. If it is clear that a patient has capacity (see British Medical Association guidelines44) and refuses treatment, then you must respect the patient's wish not to be treated for physical complications. However, in most instances good doctor-patient communication can help resolve initial uncertainties about the willingness of a patient to have treatment.

The Mental Health Act is an option if you suspect mental illness (although you should use it as a last resort, when other less intrusive options have failed). To make matters more complicated, even in this case doctors are not entitled to require physical treatment under the Mental Health Act (although they may of course do so under common law).

Is depression linked with suicide and deliberate self harm?

There is no doubt that depression is linked with completed suicide. A recent meta-analysis suggests that in all patients who suffer depression the lifetime risk of suicide is around four times higher than that seen in the general population. It is highest when depression is untreated and soon after discharge from hospital.Psychological autopsy studies reveal a rate of major depression of at least 50% in completed suicide, and similar rates appear to apply to deliberate self harm. Rates are even higher in the elderly and other vulnerable groups.

The population attributable risk explaining suicidal ideation is about:

50% for depression

40% for stressful and traumatic events

15% for low income

Furthermore, there is an extremely high correlation between severity of current depression and likelihood of suicidal thoughts. The same relationship holds in the elderly. Depression is the strongest reversible factor involved in deliberate self harm with serious suicidal intent.

The point to remember is that suicidal thoughts and behaviour are state related in depression; resolution of the depression will invariably alleviate the thoughts of suicide. The implication for practice is that you should screen all these patients for mood disorder and, when present, treat the mood disorder until it has resolved.

Should I avoid giving antidepressants in people at risk of suicide?

Antidepressants (including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) reduce active suicidal thoughts over a complete course of treatment. In short term drug trials there is an increased risk of suicidal thoughts in those aged under 25 years. However, because completed suicide is relatively uncommon the effects of antidepressants on suicide are difficult to study.You should use antidepressants to treat depression after deliberate self harm, but a case has not been made for treating people who self harm who are not depressed. In December 2004 the Medicines Control Agency issued a warning about inappropriate prescribing in adults (such as doses above the limits listed in the British National Formulary), but it recognised the importance of treating depression. In young people there may be a small short term increase in the risk of suicidal thoughts with SSRIs.

There is a clear danger of over reacting if we stop using antidepressants for depression or anxiety but do not use anything in their place, leaving the patient untreated. However, if you have access to psychological therapies it makes sense to use them too. It is sobering to remember that fewer than one in 10 patients who are depressed in the community receive adequate doses of antidepressants, regardless of their suicide risk. It is important, therefore, to present a balanced view.

Putting it into practice

Find out about local training and supervision for junior doctors in accident and emergency medicine (and psychiatry)Is there a way to flag multiple attenders or other high risk patients presenting at accident and emergency departments?

Do you have safe and private facilities to see patients?

Is there a system in place to manage deliberate self harm (including complex presentations) within four hours?

Do you know how to respond if a person you are concerned about wants to leave without completing treatment?

Communicate to other services as quickly and clearly as possible after deliberate self harm to help prevent patients getting lost to follow up.