Dementia Delirium Dystonia

د. حسين محمد جمعةاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2010

Dementia: diagnosis and assessment

Dementia is common: it affects one in five or six patients in acute hospitals, with higher prevalences in geriatric and orthopaedic trauma units. Dementia causes great distress for patients and families. It is essential that hospital doctors are able to recognise it so they can provide appropriate management in hospital, and so that the future needs of the patient are addressed. Many patients with dementia in acute hospitals are not diagnosed and managed appropriately. This module focuses on dementia of late onset."Introduction

The term dementia covers several syndromes of largely irreversible neurodegenerative disorders that result in severe cognitive decline, personality and behavioural changes, disability, and premature death. The main causes of dementia of late onset are:• Alzheimer's disease

• Vascular dementia

• Dementia with Lewy bodies.

Many have mixed Alzheimer's and vascular dementia. Dementia affects 5% of people aged 65 and 20% of people aged 80. in a general hospital with 500 beds 100 patients will have dementia.

Knowing that a patient in hospital has dementia is crucial because it will have a bearing on virtually every aspect of their management. Dementia increases the risk of developing delirium, necessitates vigilance when prescribing to avoid drugs that worsen cognition, may hinder the individual's progress through rehabilitation; is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and length of stay; and requires careful communication with patients and their relatives to ensure timely and safe discharge.

However, many patients with dementia in acute hospitals and in the community are not recognised or managed appropriately. Many patients are never formally diagnosed; instead they are described as being "poor historians" or as having "chronic confusion" or "memory impairment." Most never receive appropriate specialist care, unlike patients with other complex, serious conditions such as Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, or motor neurone disease.

All patients with dementia should receive a formal and documented diagnosis and have the opportunity to receive appropriate specialist care, mirroring recent improvements in the care of patients with stroke and Parkinson's disease. Better identification of patients with dementia improves discharge planning, reduces the incidence of delirium, and allows community support to be targeted better to the patient and carer along with access to therapies for dementia.

Abbreviated mental test scores on their own are not diagnostic.

There are many reasons why an individual may score poorly, for example having dementia, depression, delirium, or poor hearing, English not being the patient's first language, or having low baseline cognitive ability (eg learning disability).Learning bites

In the absence of a focal neurological deficit a CT scan of the brain is likely to be normal or to show non-specific atrophy and white matter changes. But the result can occasionally be unexpected. For example it could show a tumour or a chronic or acute on chronic subdural collection. It is important to remember that such patients do not always give a history of falls and lack focal neurological signs in about 30% of cases.Learning bite

Cognitive tests are diagnostic aids rather than definitive tests. You need to interpret them in the light of knowledge of the patient, the testing environment, and the limitations of the tests. The mini mental state examination and other cognitive tests can be useful screening tools but you should not use scores in isolation to make a diagnosis of dementia. We recommend that you use cognitive screening tools that you are familiar with and that you be aware of their limitations.The mini mental state examination

has several limitations. The most important ones are:Scores are influenced by level of education. A score of 28/30 might indicate impairment in a professor of Economics, but a score of 24/30 might be normal for a person with a lower educational level.

Serial subtraction of 7s is more difficult than spelling "world" backwards. This is important because five points are allocated to this task. If the patient cannot do serial 7s or refuses to do this then the tester is instructed to ask the patient to spell the word "world" backwards. A patient who attempts serial 7s but does poorly might score lower than a patient with worse cognitive impairment who has done well on spelling "world" backwards

The mini mental state examination is biased towards verbal and memory testing and does not assess executive and visuospatial functioning well and indeed may miss a fronto-temporal dementia: further testing such as with the clock drawing test (eg CLOX 1) is necessary. This is important because executive and visuospatial dysfunction are the most prominent cognitive deficits in patients with early dementia with Lewy bodies or vascular dementia, with relative sparing of memory

In inexperienced hands sensory and physical limitations can result in the patient scoring poorly even if their cognitive function is not impaired. Do remember to make allowance in the scoring if the patient is unable to complete the test due to poor visual acuity or tremor.

Despite these caveats the mini mental state examination is a useful screening tool when used with the history and other tests. In the absence of delirium or another major cause of cognitive impairment a cut off point of 23 or 24 out of 30 provides acceptable sensitivity and specificity for moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. However, adding a clock drawing task, such as CLOX 1, improves the sensitivity to other dementias considerably.

Other screening tools that aim to cover language, memory, executive and visuospatial function include the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination Revised (ACE-R) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Scale (MoCA). The ACE-R takes around 20-25 minutes to complete, it taps various cognitive domains, performance in each domain is reported as separate sub-scores which is helpful in differentiating between different dementing conditions such Alzheimer’s disease, fronto-temporal dementia, progressive aphasias, posterior cortical atrophy, and so on. The ACE-R has the MMSE and Clock Drawing Test embedded within it and the MMSE score is obtained as a sub-score at the end of the test. The MoCA was specifically designed to delineate Minimal Cognitive Impairment (MCI) subjects both from the mildly demented and the normal elderly.

Learning bite

Cognitive impairment may be due to acute or chronic impairment, or a mixture of both. There are also qualitative differences between dementia and delirium (inattention, fluctuating course, altered arousal) that can help you make this distinction. You can use more formal and validated tests to help determine whether the impairment is acute or chronic, or both.The Confusion Assessment Method is a diagnostic algorithm designed to screen for delirium. To score positive the patient must have an acute onset or a fluctuating course of cognitive impairment, or both, and they must have inattention. They should also have either disorganised thinking or altered arousal.

The informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE) is a well validated scale in which a relative or other person who knows the patient well is asked 16 questions about change in cognition over the previous 10 years.4 (In the absence of anyone who has known the individual for more than 10 years the IQCODE may be completed by the person who has known the individual for some years.)

Learning bite

Patients with significant chronic cognitive impairment and evidence of chronic impairment in personal, social, or occupational functioning by definition have dementia. After excluding depression, thyroid dysfunction, and vitamin B12 or folate deficiencies, plus other possible causes as suggested by the clinical features (for example space occupying lesions), you should strongly consider referring the patient to a specialist clinic.To make a diagnosis of delirium there must be evidence of inattention and either disorganised thinking or altered arousal. Furthermore, these impairments have to be of acute onset or show a fluctuating course, or both. These features are incorporated into the confusion assessment method. Patients with delirium always show some cognitive impairment, but this can fluctuate in severity. There are often other features such as hallucinations, mood disturbance, paranoia, and sleep disturbance. This patient's history and cognitive deficits most strongly suggest delirium.

A patient with delirium who appears lucid during the day may not have recovered to a level where discharge is safe. Further assessment is often appropriate, especially if the patient lives alone. However, ongoing delirium is not always a reason to prevent discharge; indeed, it may resolve more quickly if the patient is in their own environment. Discharge is possible if the patient is improving, is being discharged to a safe environment (for example with appropriate family or social service support), and follow up by the GP or health visitor is arranged.

Learning bite

Delirium is important in its own right as a marker of acute illness and you should manage all affected patients as medical emergencies. Jet lag is a useful metaphor for delirium: resolving the precipitant of delirium does not immediately result in return to prior cognitive function. In fact, delirium may persist for many months. Delirium also fluctuates and patients should be discharged only if there is clear evidence that they are improving and that discharge is safe.Many older patients have mild cognitive impairments but this does not always signify dementia. It could be that her delirium has not completely resolved; 20% of patients will still have symptoms of delirium six months after the precipitant has been removed. You should repeat the cognitive assessment in a few weeks' time.

Patients with mild cognitive impairment are at increased risk of progression to dementia, but many do not decline at all or decline only slightly. In this patient it is not clear yet whether her cognitive ability has returned to her best or is still recovering. You should reassess her in a few weeks' time. Because she has previously been managing in her own home it would be wrong to consider placement in a care home.

Learning bite

Dementia is not defined solely by cognitive impairment. Evidence of chronic, progressive impairment in at least two domains (for example memory and executive functioning) is required, plus evidence of new impairment in daily activities. Many older people show some mild cognitive impairment and although this is a strong risk factor for dementia, progression to dementia is not inevitable.Dementia with Lewy bodies

Other than progressive cognitive decline (an essential and defining feature of all dementias) dementia with Lewy bodies is characterised by three further features:• Fluctuating alertness and attention

• Visual hallucinations

• Parkinsonism.

Affected patients may stare into space for long periods and be unresponsive to changes in the environment. At other times they may be able to participate in normal conversation. Arousal also fluctuates, sometimes from stupor to normal levels of vigilance and responsiveness. Another important point is that patients are hyper-responsive to antipsychotic drugs, such that very small doses may cause profound sedation, worsening parkinsonism, and even death.

Cognitive decline : person who is experiencing cognitive decline may have trouble learning, using language or remembering things.

Mild Cognitive Impairment is characterized by decline in cognitive abilities (memory, concentration, orientation), and functional abilities (difficulties completing complex work-related tasks and daily activities) that correspond to pathological changes in certain parts of the brain. Researchers are studying these various changes in the brain as potential causes for Mild Cognitive Impairment. These mild impairments often, but not always, represent a very early stage of a dementia disorder, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Vascular dementia

Patients with vascular dementia may have a stepwise deterioration in both physical and cognitive function, for example in the context of a stroke. However, some patients have a gradual onset. Hallucinations are uncommon except in the setting of a complication of delirium. Parkinsonism may occur as a result of vascular damage to the basal ganglia or the motor projections to the frontal premotor cortex.It can be difficult to differentiate vascular dementia from Alzheimer's disease, but the diagnosis of vascular dementia is suggested where executive deficits and cognitive slowing are more prominent than memory deficits, there are focal neurological signs, the impairments occur in the context of a stroke, and there is evidence of cerebrovascular disease on a CT scan or on magnetic resonance imaging.

Frontotemporal dementia refers to a group of conditions in which behavioural or language impairments predominate and there is a relative preservation of memory. Patients often present with disinhibition and other behavioural impairments, or marked deterioration in language out of proportion to other cognitive deficits. There is often a family history and onset is earlier than with Alzheimer's disease (mean age is 60).

Learning bite

Patients with chronic, fluctuating cognitive impairment, hallucinations, and parkinsonism may have dementia with Lewy bodies. Patients with these features should be assessed by a specialist because they may benefit from treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors. Both they and their carers will need longer term support.Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia overlap to a considerable degree and because Alzheimer's disease is common, mixed dementia is much more common than pure vascular dementia. It is difficult to determine the diagnosis because many of the features are shared. Vascular dementia is thought to be more likely if, for example, there is a clear background of atherosclerosis, executive rather than memory deficits are prominent, there is relative preservation of personality, and there are focal neurological symptoms and signs. Vascular dementia may result from any blood vessel related damage to the brain, including a single stroke, multiple strokes (lacunar syndrome), and Binswanger's disease (progressive deep white matter damage thought to be due to atherosclerosis).

However, conventional vascular risk factors such as diabetes mellitus are now known to increase the risk of Alzheimer's disease. In many patients, therefore, there are several overlapping pathological processes, including accumulation of beta amyloid plaques and ischaemic damage to neurones, which are operating in parallel or synergistically to give rise to the clinical features.

Prescribing cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease and other dementias is a controversial and evolving area. NICE recommends using these drugs only in patients with moderate Alzheimer's disease, defined by NICE as mini mental state examination scores between 10 and 20 (although there are certain caveats: see the guideline).The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network takes a different view, recommending treatment in patients with all severities of disease and in patients with mixed dementia (Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia). There is also some evidence that cholinesterase inhibitors are effective in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease dementia .

Learning bites

The Delirious about Dementia consensus statement (from the British Geriatrics Society) on improving care of patients with dementia included a proposal for a case register system for patients with dementia. This would help in providing consistent, integrated health and social care. In the proposed system patients with possible dementia identified in a general hospital would be referred to an old age psychiatrist for further evaluation. Care from all the relevant services would be planned and coordinated from that point onwards.

Some 15-20% of patients in general hospitals have dementia, which is a large number. But many of these patients are not diagnosed in primary or secondary care. This means patients are not given the opportunity to be told the diagnosis and plan future care. They are also denied the opportunity to access specialist care.

A detailed history of cognitive ability including a mental state examination should take around 30 minutes. Given that dementias are fatal, progressive brain disorders this is not an excessive amount of time.

Remember that thyroid function tests may not be useful in the context of acute illness.

Given the strong possibility of dementia from the patient's history a universal screening tool, such as the abbreviated mental test, is not adequate. The mini mental state examination, although more detailed, is weighted towards memory and verbal function. This is a problem because abnormalities of executive and visuospatial functioning are sometimes more prominent in people with dementia. Adding a clock drawing task such as the CLOX 1 is therefore essential.

If the mini mental state examination score is very low (less than 15) it is unlikely that the clock drawing test will add much to your assessment. But such a low mini mental state examination score is unlikely in a woman who lives alone.

A detailed neuropsychological assessment is not always needed when making a diagnosis of dementia, but if you are unsure about the diagnosis the assessment can be helpful. However, this is normally arranged via a memory clinic after a consultation with a specialist geriatrician or psychiatrist.

An acute decline in cognition with fluctuating conscious level, inattention and rambling, or incoherent responses is typical of delirium. Old age and dementia are the most important predisposing factors for delirium.

Untreated depression may cause chronic cognitive impairment mimicking dementia, although the individual usually performs much better on cognitive testing than their complaints would suggest that they should. Also, the answers they give on cognitive testing often suggest they know the correct answer but give an approximation instead.

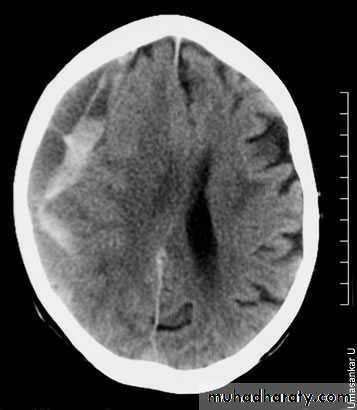

There is an acute on chronic right subdural collection with a depth of at least 2.5 cm. There is associated oedema of the right cerebral hemisphere with an approximately 1 cm midline shift to the left. This is an acute on chronic subdural haemorrhage. Patients with a subdural haematoma do not always have a history of falls.

•

Dementia with Lewy bodies is marked by cognitive impairment, fluctuations in alertness and cognition, and visual or auditory hallucinations. Parkinsonism is often present but it is usually not severe and there is less tremor than in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Dementia commonly complicates idiopathic Parkinson's disease but the motor symptoms and signs present first and predominate. The division between dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease with dementia is arbitrary. Extrapyramidal signs and dementia occurring within one year of onset of each other is defined as dementia with Lewy bodies. If cognitive impairment occurs beyond a year then it is defined as Parkinson's disease with dementia.

Alzheimer's disease,, the symptoms came on slowly and progressed gradually. short term memory and word finding ability are particularly affected, which is typical of Alzheimer's disease.

Sudden onset of symptoms and stepwise deterioration suggest vascular dementia. The patient often has risk factors for cerebrovascular disease. Features of dementia with Lewy bodies include parkinsonism, memory impairment, and visual hallucinations. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease is a rare cause of dementia that is typically of rapid onset and is associated with myoclonus.

There is evidence of widening of the cortical sulci, subarachnoid spaces, and ventricular cistern denoting involutional brain changes. The occipital horn of the left lateral ventricle is noticeably dilated and associated with a large cerebral spinal fluid space, replacing brain tissue of the left occipital lobe. This may denote a sequel of a previous large infarction. There is cerebral atrophy. Cerebral atrophy is more common in patients with dementia, but it is not sensitive or specific enough to be used as a diagnostic marker for dementia. CT scans are used to exclude structural and potentially treatable causes of dementia, such as brain tumours and normal pressure hydrocephalus.

Vascular dementia is a common form of dementia. But there is increasing evidence that the pathological processes thought to underlie Alzheimer's disease (predominantly beta amyloid deposition and accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles) are often mixed with vascular changes. The presenting features of vascular dementia are diverse, but typically the memory deficits are not as prominent as in Alzheimer's disease, with executive deficits (that is problems with Sequencing, Organising, Abstracting, and Planning) and cognitive slowing being prominent. This is why it is important not to rely solely on memory tests when screening for dementia.

Many overlapping pathological processes can cause the vascular dementia syndrome, including stroke, lacunar infarcts, and small vessel disease.

Dementia with Lewy bodies:

a guide to diagnosis and treatment

Learning outcomes

After completing this module you should:Know the clinical criteria for diagnosing dementia with Lewy bodies

Be able to develop an approach to treating patients with dementia with Lewy bodies

Remember to avoid prescribing typical antipsychotics when treating patients with dementia with Lewy bodies.

Dementia with Lewy bodies is the second most common form of degenerative dementia after Alzheimer's disease. Determining which type of dementia the patient has can help tailor specific treatments, while choosing the wrong treatment can harm patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. This module therefore provides practical guidance on the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies."

Key points

Dementia with Lewy bodies is a common and important cause of dementiaThe condition is characterised by dementia accompanied by fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, and parkinsonism.

Other common symptoms include syncope, falls, sleep disorders, orthostatic hypotension, urinary incontinence, and depression

The presence of both Lewy bodies and amyloid plaques with deficiencies in acetylcholine and dopamine neurotransmitters suggests that dementia with Lewy bodies represents the middle of a disease spectrum ranging from Alzheimer's disease to Parkinson's disease.

The diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies is based on clinical features and excluding other diagnoses, although MRI, SPECT, and MIBG myocardial scintigraphy can be helpful

Individualised behavioural, environmental, and pharmacological therapies are used to alleviate symptoms and support patients and their families

You should avoid prescribing typical antipsychotics.

Clinical tips

Develop a problem list with the patient, family, and caregiver to know what symptoms to prioritise when it comes to treatment options.

Treatment in one area may be at the expense of losses in another

Strictly avoid prescribing anticholinergic and typical antipsychotic medications.

Anticholinergics may exacerbate the symptoms of dementia and typical antipsychotics may double or triple the rate of mortality in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies.

Refer patients to a specialist if the diagnosis is uncertain, difficult symptoms are present, the disease process is atypical, or treatment seems to be complicated

What is it?

Dementia with Lewy bodies is an emerging disease first described in 1984 by Kosaka and colleagues. They reported finding Lewy bodies (eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions) throughout the cortexes of some patients with dementia. This was in contrast to the typical extracellular amyloid neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles characteristic of Alzheimer's disease distributed in the parietal, temporal, and parieto-occipital cortex.Lewy bodies are known to be in the brainstem of patients affected by Parkinson's disease (predominantly in the midbrain substantia nigra and locus ceruleus).

Dementia with Lewy bodies is characterised by the presence of Lewy bodies in both the subcortical and cortical (frontotemporal) regions of the brain. Patients with dementia with Lewy bodies also often have cortical amyloid plaques (although the neurofibrillary tangles found in Alzheimer's disease are less common in dementia with Lewy bodies).

Biochemically, Alzheimer's disease is associated with a deficit in the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Parkinson's disease is associated with a deficit in the neurotransmitter dopamine. Dementia with Lewy bodies is associated with deficits in both acetylcholine and dopamine. Clinically, dementia with Lewy bodies is characterised by dementia, often associated with parkinsonian symptoms. Therefore, pathologically, biochemically, and clinically, dementia with Lewy bodies appears to fall somewhere in the middle of a disease spectrum ranging from Alzheimer's disease to Parkinson's disease .

Comparison of dementia with Lewy bodies with Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.

Signs of diseaseAlzheimer's disease

Dementia with Lewy bodies

Parkinson's disease

Clinical signs

Dementia

Early impairment of memory and attention

Early disturbance in attention and visual perception

No early impairment

Fluctuating cognition

Occasional

Typical

Rare

Visual hallucinations

Occasional

Typical

Occasional

Delusions

Occasional

Typical

Occasional

Parkinsonism

Rare

Within one year of onset of dementia

First manifestation

Autonomic dysfunction

Rare

Typical

Typical

Rigidity

Occasional

Typical

Typical

Bradykinesia

Occasional

Typical

Typical

Tremor

Rare

Occasional

Typical

Biochemical signs

Cholinergic deficit

Typical

Typical

Occasional

Dopaminergic deficit

Rare

Typical

Typical

Who gets it and why?

Dementia with Lewy bodies is the second most common histopathology found in dementia, and the number of patients is expected to increase as the population ages and as dementia with Lewy bodies is increasingly recognised. Dementia with Lewy bodies accounts for about 20% of patients with dementia.No specific risk factors for dementia with Lewy bodies have been identified other than possibly a family history of dementia. Although alterations of alpha-synuclein protein seem to play a pivotal role in dementia with Lewy bodies and genetic mutations causing overproduction of alpha-synuclein have been described, these mutations are not felt to be a common cause of dementia with Lewy bodies.14

How do I diagnose it?

The diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies can be challenging because it is primarily based on clinical features and excluding other diagnoses. Another clinical difficulty is that dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease can be present in the same person.The cardinal features of dementia with Lewy bodies are:

Dementia• Fluctuating cognition

• Visual hallucinations

• Parkinsonism.

Some authors have included sensitivity to antipsychotic agents or rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder as defining characteristics. These, however, are now included in the consensus guidelines as "suggestive" features.

Dementia

Patients with dementia with Lewy bodies tend to have difficulty with executive functioning, such as:

• Sequencing items

• Planning

• Prioritising.

Additionally they have visuospatial impairment to a greater degree than those with Alzheimer's dementia. Using traditional diagnostic methods for these patients, such as the mini mental state examination, will typically reveal less impairment with memory but more difficulty completing tasks such as figure copying or clock drawing. The presence of visuospatial or constructional dysfunction and visual hallucinations have been found helpful in distinguishing dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer's disease.

Fluctuating cognition

Fluctuating cognition is a key feature that can help differentiate dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia. About 50-75% of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies exhibit these types of fluctuating symptoms, sometimes referred to as "pseudodelirium," because they can occur over minutes, hours, or days. You should not, therefore, attempt to make a diagnosis solely based on the patient's current cognitive state, but should instead rely more on accounts given by family members or caregivers who may have observed this type of behaviour.Of note, four differentiating characteristics between patients with dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease have been found in a recent study. Some 63% of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies exhibited three out of four of these, compared with only 12% of patients with Alzheimer's disease. The characteristics are:

• Daytime drowsiness and lethargy

• Daytime sleep of two or more hours

• Staring into space for long periods

• Episodes of disorganised speech.

Visual hallucinations

Frequently, patients who have dementia with Lewy bodies are noted to have vivid, colourful, three dimensional, purely visual hallucinations. In fact, nearly 80% of patients exhibit some psychotic symptoms as part of their disease process and not an additional psychotic illness. This is an important distinction because these patients can have severe reactions to antipsychotic medications. Visual hallucinations and visuospatial or constructional dysfunction may be the most useful way to differentiate dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer's disease.Parkinsonism

Parkinsonism and dementia must present within one year of each other in a patient to make a diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. This key feature differentiates this disease from Parkinson's disease with dementia, since in the latter condition the motor impairment is typically present for many years before the development of dementia. Also of note, the typical tremor seen in Parkinson's disease is often absent in dementia with Lewy bodies. Instead, rigidity, falls, and bradykinesia are the typical motor deficits. Further, patients with dementia with Lewy bodies sometimes have important autonomic symptoms, such as orthostatic hypotension and constipation. Unfortunately the use of levodopa or carbidopa does not usually give the same level of symptomatic relief as in patients with Parkinson's disease.Other features

Urinary incontinence, another autonomic dysfunction that often occurs early in the progression of the disease, can help differentiate this condition from Alzheimer's disease.23 Patients may also show carotid sinus hypersensitivity and postural hypotension because of the impairment of the autonomic system.2 Additionally, many patients with dementia with Lewy bodies show signs of depression.

Nearly 50% of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies have rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder,19 24 which is characterised as having vivid dreams associated with simple or complex motor behaviour during sleep.8 These patients will sometimes act out these dreams to the point of trying to defend themselves against a perceived attack, which can be distressful for their partners.22 25

Dementia with Lewy bodies has no characteristic laboratory findings that distinguish it from other forms of dementia. Appropriate investigations are identical to those for other forms of dementia and should include:

Routine screening for depression

Vitamin B-12 and folate deficiencies

Hypothyroidism (plus syphilis or HIV in people who may have been infected previously).

Similarly, although computed tomography (CT) may be indicated as part of the general work-up for dementia, there are no distinctive findings in patients who have dementia with Lewy bodies. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in dementia with Lewy bodies shows preservation of hippocampal and medial temporal lobe volume compared with Alzheimer's disease, whereas single photon emission CT reveals occipital hypoperfusion. Recent studies suggest combining MR and SPECT helps differentiate dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer’s disease

Another study suggests MIBG myocardial scintigraphy may be superior to SPECT, and the combination of the two could increase the accuracy of clinical diagnosis. Although specialised imaging such as single photon emission (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET) perfusion or MIBG myocardial scintigraphy scans may be diagnostically useful (see "Supportive features" in the revised consensus guidelines below1), these imaging modalities are not commonly used diagnostically in primary care.

The key clinical features are defined in the 2005 consensus guidelines published after the third international workshop of the Consortium on Dementia with Lewy Bodies. They distinguish probable and possible dementia with Lewy bodies. According to these guidelines, to make a probable diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies a patient must have dementia with at least two core features or one core and one suggestive feature of the disease. You can make a diagnosis of possible dementia with Lewy bodies if only one core or one suggestive feature is present in the patient .

Revised consensus guidelines for the clinical diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies

Central feature(Needed for a diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies.)

Dementia, which is defined as:

• Progressive cognitive decline of sufficient magnitude to interfere with normal social or occupational function

• Prominent or persistent memory impairment, which does not necessarily occur in the early stages but is usually evident with progression

• Deficits on tests of attention, executive function, and visuospatial ability may be especially prominent.

Core features

(Two sufficient for a probable diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies, one for a possible diagnosis.)

Fluctuating cognition with pronounced variations in attention and alertness

Recurrent visual hallucinations that are typically well formed and detailed

Spontaneous features of parkinsonism

Supportive features

(Commonly present but not proved to have diagnostic specificity.)Repeated falls and syncope

Transient, unexplained loss of consciousness

Severe autonomic dysfunction, for example, orthostatic hypotension or urinary incontinence

Hallucinations in other modalities

Systematised delusions

Depression

Relative preservation of medial temporal lobe structures on CT and MRI scan

Generalised low uptake on SPECT or PET perfusion scan with reduced occipital activity

Abnormal (low uptake) meta-iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) myocardial scintigraphy

Prominent slow wave activity on an electroencephalogram with temporal lobe transient sharp waves

Suggestive features

If one or more is present with one or more core features, you can make a diagnosis of probable dementia with Lewy bodies. In the absence of any core features, one or more suggestive features is sufficient for a diagnosis of possible dementia with Lewy bodies. You should not diagnose probable dementia with Lewy bodies on the basis of suggestive features alone.Rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder

Severe neuroleptic sensitivity

Low dopamine transporter uptake in basal ganglia demonstrated by SPECT or PET imaging

A diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies is less likely:

In the presence of cerebrovascular disease evident as focal neurological signs or on brain imaging

In the presence of any other physical illness or brain disorder sufficient to account in part or in total for the clinical picture

If parkinsonism appears only for the first time at a stage of severe dementia

Temporal sequence of symptoms

You can make a diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies when dementia occurs within one year of the onset of parkinsonism (if it is present).Use the term Parkinson's disease dementia to describe dementia that occurs in the context of well established Parkinson's disease. In practice you should use the term that is most appropriate to the clinical situation and generic terms such as Lewy body disease are often helpful.

In research studies in which a distinction needs to be made between dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease dementia, the existing one year rule between the onset of dementia and parkinsonism dementia with Lewy bodies is recommended.

How should I treat it?

An initial accurate diagnosis, along with both non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatments, is important.Non-pharmacological treatment

Non-pharmacological treatments are felt to be important and helpful for treating any dementia, but they have not been systematically evaluated in dementia with Lewy bodies. These could include:

Improving sensory impairments (glasses or hearing aids)

Educating the patient and family.

Improving environmental structure (reducing shadows and minimising patterned carpets or wallpaper).

Teaching behavioural interventions.

Since dementia is progressive and incurable, you should give early attention to advance care plans and end of life decisions involving both the patient and the carer. In addition you can address carer support and education, respite care, and support by the community mental health team. Finally, you can establish collaboration between primary care, specialists (geriatrician, psychiatrist, or neurologist), and health and social care specialists. Select the interventions to address the specific needs of each patient and their caregivers. For example, hallucinations can be managed by simple observation and education of the caregivers, as well as by environmental changes such as improving vision and lighting and increasing the number of people in the environment.Pharmacological treatment

The pharmacological treatment of dementia with Lewy bodies can be challenging because treating one aspect of the disease may worsen another. For this reason, working with the patient and carer to develop a problem list can be helpful. Identifying which symptoms are most disabling and distressing should help you to decide on the right treatment.

When to refer

Refer patients to a specialist if:

The diagnosis is uncertain

You can't develop a treatment strategy for the patient's disease process

Difficult symptoms are present

You or the patient's family is uncomfortable with the diagnosis or treatment

What pharmacological therapies can I use?

Pharmacological therapies should be based on the problem list developed with the patient and family. Identifying and prioritising problems with extrapyramidal motor features, cognitive impairment, neuropsychiatric features (for example, hallucinations, depression, sleep disorder, and associated behavioural disturbances), or autonomic dysfunction is important because treatment in one area may be at the expense of losses in another.8 For example, the use of cholinesterase inhibitors for dementia may exacerbate parkinsonian features such as drooling and postural instability, while the use of dopaminergic agents for parkinsonism can exacerbate psychotic symptoms.In general, cholinesterase inhibitors are the most effective medications for the dementia, fluctuating cognition, and visual hallucinations. Rivastigmine has been the best studied. Cholinesterase inhibitors are usually well tolerated at standard doses. The primary side effects are gastrointestinal.

One study suggested memantine had positive effects on patients’ general status and cognitive functions mainly because of improvements in attention and control functions.

Pharmacological treatment if the most distressing problem is motor parkinsonism (bradykinesia)

Levodopa is the primary medication used to treat the motor disorders of dementia with Lewy bodies. However, it is not very effective in the treatment of parkinsonism in dementia with Lewy bodies. Unfortunately, it can also worsen psychotic symptoms, hypersomnolence, and postural hypotension. Start dosages low and increase them slowly to the minimum dosage necessary to control the motor disability without exacerbating psychiatric symptoms. You should avoid all dopaminergic therapies other than levodopa because they can worsen psychosis. The goal of antiparkinsonian treatment should be to improve mobility without inducing or exacerbating psychotic symptoms or confusion.

Pharmacological treatment if the most distressing problem is neuropsychiatric symptoms

Visual hallucinationsThese are the most common neuropsychiatric symptom. They can be associated with delusions, anxiety, and behavioural problems. If they do not bother the patient, they may not need any treatment. Since dopaminergic agents can exacerbate hallucinations and delusions, tapering these agents is typically the first step in managing psychosis. Cholinesterase inhibitors are the most effective medications for neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Patients with strong visual hallucinations are reported to have a better response to cholinesterase inhibitor therapy than other patients with dementia. Side effects include hypersalivation, lacrimation, urinary frequency, gastrointestinal symptoms, and a dose dependent exacerbation of extrapyramidal symptoms. If necessary you may want to try low doses of the newer atypical antipsychotics (quetiapine 12.5-25 mg and titrate to effectiveness).

Depression

Depression in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies is common. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are preferred treatments,although there are few systematic studies. You should avoid tricyclic antidepressants because of their anticholinergic properties.

Sleep disorders

Sleep disorders are an important aspect of dementia with Lewy bodies, and treatment is reported to improve fluctuations in cognition and markedly benefit quality of life for both patients and their families.8 Patients with rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder may respond to clonazepam, 0.25 mg to 1.0 mg, at bedtime, although use of this drug may be limited by ataxia and morning sedation.Treatments to avoid

You should not treat patients with dementia with Lewy bodies with the older, typical D2-antagonist antipsychotic agents such as haloperidol, fluphenazine, and chlorpromazine. About half of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies who receive these older neuroleptic medications experience life threatening side effects characterised by the acute onset or exacerbation of parkinsonism and impaired consciousness (sedation, rigidity, postural instability, falls, increased confusion, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome), with an associated two- to threefold increase in mortality. For this reason, you should document this in the records and inform caregivers. Atypical antipsychotics can cause similar problems.Since only 50% of patients treated with antipsychotics react adversely, neuroleptic tolerance does not exclude a diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. A severe reaction to neuroleptics is suggestive of dementia with Lewy bodies.

You should strictly avoid anticholinergic agents.

Parkinsonism and dementia must occur within one year of each other in a patient to make a diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. This key feature differentiates this disease from Parkinson's disease with dementia. In the latter condition, the motor impairment is typically present for many years before the development of dementia.

Visual hallucinations are a core symptom of dementia with Lewy bodies.

Depression is a supportive feature of dementia with Lewy bodies.Severe sensitivity to neuroleptics is a suggestive feature of dementia with Lewy bodies.

Severe autonomic dysfunction is a supportive feature of dementia with Lewy bodies.

Transient, unexplained loss of consciousness is a supportive feature of dementia with Lewy bodies.

According to the consensus guidelines, a patient must have either two core features or one core feature and one suggestive feature to be diagnosed with probable dementia with Lewy bodies

Improving sensory impairment with glasses or hearing aids

Prescribing cholinesterase inhibitors to treat visual hallucinations

Prescribing clonazepam for rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the preferred treatment for depression.

a : Alzheimer's disease

The symptoms came on slowly and progressed gradually. short term memory and word finding ability are particularly affected.b : Vascular dementia

Sudden onset of symptoms and stepwise deterioration suggest vascular dementia. The patient often has risk factors for cerebrovascular disease.

c : Dementia with Lewy bodies

Features of dementia with Lewy bodies include parkinsonism, memory impairment, and visual hallucinations.

Dystonia: a guide to assessment and management

Approximately 70 000 people in the United Kingdom are affected by dystonia, a prevalence of around 1 in 900.Living with dystonia can be stressful as it often causes significant pain and discomfort, and it may have a major impact on a person's work and social life. The involuntary muscle spasms can be extremely debilitating and painful, as well as embarrassing and stigmatising. For these reasons it can have a considerable negative effect on a person's quality of life.

Treatment can alleviate the symptoms of dystonia, however, so it is vital that patients are assessed, diagnosed, and managed appropriately.

Learning bite

There is currently no definitive test for dystonia, and the recognition of characteristic signs and symptoms is required for a diagnosis.Essential tremor is another differential diagnosis. There is typically a postural tremor in both hands. There is often a family history and it is sometimes relieved by alcohol and by beta blockers.

Ptosis may occur following injection of botulinum toxin for blepharospasm due to excessive weakness of the orbicularis oculi caused by the injected toxin.

Learning bite

Botulinum toxin injections usually need to be repeated every 10 to 12 weeks, and are not typically repeated more frequently than every eight weeks as there is a risk of resistance or antibody development.

Dystonia is a movement disorder characterised by involuntary and sustained muscle spasms and contractions that produce abnormal twisting postures or repetitive movements. It can affect the eyes, face, neck, speech, limbs, and trunk

In the United Kingdom prevalence of approximately 1 in 900 Living with dystonia can be stressful as it often causes significant pain and discomfort, and it may have a major impact on a person's work and social life. can be extremely debilitating and painful, as well as embarrassing and stigmatising. For these reasons it can have a considerable negative effect on a person's quality of life

You should not try to treat patients presenting with dystonic symptoms before a definitive diagnosis has been made .There are several options for management, but the majority of the available treatments offer symptomatic relief only. You should also consider reversible treatments prior to any surgical or non-reversible drug treatments

The "gold standard" treatment for most focal dystonias

is botulinum toxin injections into the overactive muscles to block the nerve action on the muscles

Some patients with dystonia respond to anticholinergic drugs (for example, trihexyphenidyl), a benzodiazepine, or baclofen. The choice of treatment usually depends on the patient's age, prior treatment attempts, and other concurrent medication or medical problems. The general strategy is to start treatment with a low dose, and gradually increase it as tolerated and required. If the treatment is not beneficial at a dose that causes adverse effects, then it is gradually tapered and discontinued before the next drug is tested. If it does alleviate symptoms, it can be continued and additional medication tried if necessary be required

Pallidal deep brain stimulation may help cervical dystonia and generalised dystonia, if less invasive methods offer no benefit Selective peripheral denervation may help cervical dystonia. This involves cutting the nerves to the muscles of the neck Intrathecal baclofen may occasionally help patients with more severe forms of dystonia

In order to ensure that patients with dystonia can maintain and optimise their independence, you should support them in accessing any mobility and daily living equipment .

• Learning bites

• In general, dystonia is:• Task or position specific

• Mobile rather than fixed

• Caused by co-contraction of the agonist and antagonist muscles. This can be felt, or detected, by (EMG)

Often improved by a sensory trick or geste antagoniste. A patient with dystonia will often be able to improve the abnormal posture by touching (or even thinking about touching) the body part affected. Focal hand dystonia is an example of task specific dystonia. The declining ability to write is typical, as is the painful muscle cramping. It is often triggered by doing repetitive tasks.

Laryngeal dystonia or spasmodic dysphonia affects the muscles of the vocal cords. The disorder may affect the adductor or abductor muscles, or both. In adductor spasmodic dysphonia the patient typically has a strangled staccato speech pattern. In abductor spasmodic dysphonia the patient has a breathy voice.

Dysphagia and pooling of saliva are the side effects that occur most frequently after an injection of botulinum toxin into the sternocleidomastoid muscle (<10%). This is due to diffusion of the toxin from the injected muscle to the nearby pharyngeal muscles. Botulinum toxin does not cause hypertension or abdominal pain. It can sometimes cause dyspnoea

Botulinum toxin partially weakens the overactive dystonic tremor and can restore normal posture, reduce the tremor, and relieve pain. Although botulinum toxin is licensed only for blepharospasm and related facial dystonia, hemifacial spasm, and cervical dystonia, it is also accepted as safe, effective, and appropriate therapy for spasmodic dysphonia, oromandibular dystonia, writer's cramp, and other focal dystonias.

Botulinum toxin injections usually need to be repeated every 10 to 12 weeks, and are not typically repeated more frequently than every eight weeks as there is a risk of resistance or antibody development.

Dystonia can be difficult to diagnose, and many patients remain untreated because their symptoms are unrecognised. There is currently no definitive test for dystonia, and the recognition of characteristic signs and symptoms is required for a diagnosis. Neurological examinations, brain scans, and blood tests may be performed to rule out secondary causes.

Learning bite

Dystonia can be of either "primary" or "secondary" origin. "primary" no identifiable cause, apart from possible genetic factors. "Secondary" dystonias are often accompanied by other neurological problems and there is an identifiable cause for the dystonia. They are associated with different hereditary metabolic and environmental causes. Environmental causes include head trauma, stroke, brain tumour, multiple sclerosis, infections in the brain, injury to the spinal cord, and a variety of drugs or toxins that affect the brain.Dystonia is defined as a neurological movement disorder characterised by involuntary muscle spasms that lead to sustained abnormal postures of the affected body part. Typically, the abnormal postures are not fixed and instead slow, sinuous, and writhing movements can occur (athetosis) in which the dominant muscle activity switches from agonist to antagonist, and back again. Tremor commonly occurs with dystonia, and it tends to affect the same body part. Dystonic tremor is typically jerky, variable in amplitude, and is worsened by particular positions of the affected limb and/or the task being undertaken.

The diagnosis should first of all be made by a specialist to exclude other, rare causes. You should not try to treat patients presenting with dystonic symptoms before a definitive diagnosis by a movement disorder specialist has been made and a management plan has been developed. Cervical dystonia affects the muscles of the neck, causing twisting movements. There is often head tremor associated with it.

This type of dystonia can be extremely painful. The condition can cause the neck to turn to the left, right, sideways, forwards, or backwards.

Delirium: a guide to diagnosis and management

Key pointsThe clinical presentation of delirium is variable between patients and over time;

hypoactive, hyperactive, and mixed subtypes are recognised.

Delirium tremens is clinically distinct from delirium.

Delirium is caused by an interplay between predisposing and precipitating factors

The differential diagnoses of a patient presenting with confusion are:

• Delirium

• Dementia

• Amnestic syndrome

• Affective disorders

• Primary psychotic disorders

The prognosis of delirium is closely related to that of the underlying condition. Delirium has a negative effect on the prognosis of the underlying condition

Clinical tips

The treatment of delirium consists of:• Treating the underlying physical condition

• Maintaining behaviour control

• Treating the associated psychiatric symptoms

Behavioural changes are best managed by behavioural means. Medication can help treat the behavioural and psychological symptoms of delirium, but you should use drugs with caution because of their side effects.

In patients who do not or cannot consent to treatment the duty of care of healthcare professionals should be weighed against the patient's rights to refuse treatment.

How does delirium present?

Delirium is a common and usually reversible syndrome occurring during a physical illness. It is most common in children and older people.Because delirium affects the brain globally, many different mental processes are affected. The ICD 10 describes delirium as a syndrome with no specific aetiology that is characterised by concurrent disturbances of consciousness and attention, perception, thinking, memory, emotion, and the sleep-wake cycle. It may occur at any age, but is most common after age 60. The delirious state is transient and of fluctuating intensity. The term acute confusional state has been used synonymously with delirium; delirium, however, is the preferred term.

For a definitive diagnosis mild, moderate, or severe symptoms should be present for each of the following:

Impairment of consciousness and attention (on a continuum from clouding of consciousness to coma; reduced ability to direct, sustain, and shift attention)

Global disturbance of cognition (perceptional distortion, illusions, and hallucinations (most often visual); impairment of abstract thinking and comprehension, with or without transient delusions but typically with some degree of incoherence; impairment of immediate recall and of recent memory, but with relatively intact remote memory; and disorientation for time as well as, in more severe cases, for place and person).

Psychomotor disturbance (hypo- and hyperactivity and unpredictable shifts from one to the other; increased reaction time; increased or decreased flow of speech; and enhanced startle reaction)

Disturbance of the sleep-wake cycle (insomnia or, in severely affected patients, total sleep loss or a reversal in the sleep-wake cycle; daytime drowsiness; nocturnal worsening of symptoms; and disturbing dreams or nightmares, which may continue as hallucinations after awakening).Emotional disturbances such as depression, anxiety or fear, irritability, euphoria, apathy, or wondering perplexity.

There are three subtypes of delirium:

• Hyperactive• Hypoactive

• Mixed.

The hyperactive form is characterised by hallucinations, delusions, agitation, and disorientation. The hypoactive form is characterised by cognitive impairment and sedation and is less often accompanied by delusions, hallucinations, and illusions. Comparable levels of cognitive impairment occur in both subtypes. In one study the relative frequencies of these subtypes were estimated as:

15% for the hyperactive type

19% for the hypoactive type

52% for the mixed type.

Some 14% of the patients were not classified in this study.

The onset is normally abrupt, over a few hours or days. The course is typically fluctuating in intensity. Relatively symptom free episodes can alternate with episodes of severe impairment, psychotic symptoms, agitation, and aggression. Symptoms are usually worse at night.

Delirium is often underdiagnosed because of:

Failing to think of the diagnosis as a possibility

Mild symptoms at the beginning of the illness

The fluctuating course.

Rates of non-detection are typically reported to be 33-66%. Education aimed at junior doctors is therefore important and can improve the diagnosis of delirium. It is important to remember that the cognitive and behavioural changes can be subtle and are therefore difficult to detect. A raised level of awareness of these changes can increase the rate of detection.

A raised level of awareness can increase the rate of detection.

How does delirium tremens present?

Is a distinct entity.

It represents the most serious phenomenon of withdrawal from alcohol,

with a mortality of up to 5%.

Withdrawal from medication and other drugs is classified as delirium rather than as delirium tremens.

The fully developed syndrome of delirium tremens consists of:

• Vivid hallucinations (especially visual)• Delusions

• Profound confusion

• Tremor

• Agitation

• Sleeplessness

• Autonomic overactivity.

This full picture is relatively rare, representing only 5% in a consecutive series of patients withdrawing from alcohol. In comparison, acute tremulousness occurs in 34% of patients and transient hallucinosis with tremor in 11% of patients.

Delirium tremens often presents in an acute and dramatic manner, although a short prodromal phase is often present. The first symptoms are normally restlessness, insomnia, and fear. The patient has vivid nightmares and repeatedly wakes in a panic. Transient illusions and hallucinations start to occur. Rats, snakes, and other small animals are typical. They are often Lilliputian in size and move quickly. Auditory and tactile hallucinations also occur.

The patient becomes tremulous and, if out of bed, is usually ataxic. There is evidence of dehydration. Restlessness can be extreme. The lack of sleep leads ultimately to physical exhaustion. Autonomic disturbance typically results in perspiration, flushing or pallor, dilated pupils, a weak rapid pulse, and mild pyrexia. Seizures occur in up to a third of patients, virtually always preceding the delirium tremens.

The degree of impairment of consciousness varies widely from patient to patient and in the same patient from one moment to the other. Often there is a diminished awareness of the environment with overarousal. Disorientation is obvious, but the degree of inattention to the environment may give the impression that consciousness is more severely impaired than it actually is.

The disorder is often of short duration, lasting less than three days. Death, if it occurs, is usually due to cardiovascular collapse, infection, hyperthermia, or injury during the phase of intense restlessness.

Epidemiology of delirium

Few epidemiological studies of delirium have been conducted in the general population outside hospitals. One such study with relatively few numbers found that the prevalence was likely to be lower than in hospitals and rises with age. The prevalence for the general population was:0.4% in those 18 years and older

1.1% in those 55 years and older

13.6% in those 85 years and older.

What causes delirium?

The causal factors in an individual patient are almost invariably multifactorial and can be divided into predisposing and precipitating factors. In general the higher the vulnerability of the patient the less severe the toxic insult needs to be to cause delirium. So whereas an elderly patient with dementia would be likely to develop delirium following a mild infection, this is unlikely to be the case in a younger patient without dementia. But almost every patient in a hospital has more than one predisposing and precipitating factor.• Predisposing factors

• Demographic and social factors• Older age

• Male sex

• Institutional setting

• Process of care

• Iatrogenesis

• Reduction in skilled nursing staff

• Sensory impairment

• Visual impairment

• Hearing impairment

Psychiatric comorbidity

Dementia

Depression

Functional impairment and disability

Malnutrition

Dehydration

Alcoholism

Medical comorbidity

Previous stroke

Parkinson's disease

Precipitating causes

Medication

Alcohol and substance misuse (intoxication and withdrawal)

Severe or acute illness

Urinary tract infection

Pneumonia

Metabolic abnormality

Hyperglycaemia or hypoglycaemia

Hypercalcaemia or hypocalcaemia

Thyrotoxicosis and myxoedema

Adrenal insufficiency

Hepatic failure

Renal failure

Hypoperfusion states

Pulmonary compromise

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Hypoxia

Shock

Anaemia

Sensory deprivation

Sleep deprivation

Pain

Surgery, anaesthesia, and other procedures

Traumatic brain injury

Neurological illnesses

Subdural haematoma

Stroke

Malignancy

Cerebral infection

Seizure, this includes partial status epilepticus, prodromal symptoms, and post seizure confusion

Medicines with a high or moderate risk of causing delirium

Medications with a high risk

Benzodiazepines

Opioid analgesics

Antiparkinsonian agents (both antimuscarinic and dopaminergic)

Tricyclic antidepressants

Lithium

Corticosteroids

Medications with a moderate risk

Digitalis

Antipsychotics

Beta blockers

Antiarrhythmics

Differential diagnoses

The differential diagnoses for cognitive impairment with or without impairment of consciousness are:Delirium

Dementia:

Alzheimer's dementia

Vascular dementia

Dementia with Lewy bodies

Amnestic syndromes

Primary psychotic disorders

Depression.

This is not a true differential diagnosis because the diagnoses are not mutually exclusive. Rather these diagnoses need to be considered alongside each other and the relationship between these conditions is complex. Dementia and delirium can and commonly do coexist because dementia is one of the main predisposing factors for the development of delirium. An episode of delirium can also precipitate dementia. Depression and its related physical problems can be complicated by delirium. Depression and dementia also often coexist.

Different types of dementia

Alzheimer's diseaseDementia of the Alzheimer's type is usually insidious in onset and presents slowly, but steadily over several years. The illness often starts with a slight impairment of memory, especially of new material, and progresses to involve all higher cognitive functions.

Features that are attributed to delirium and Alzheimer's disease

FeaturesDelirium

Alzheimer's disease

Onset

Acute or subacute onset (hours or days)

Insidious (usually several years)

Frequent and rapid fluctuations (hours)

Slow changes (months)Rapid functional decline

Relatively slow functional declineConscious level

Attention markedly reduced

Attention reduced only in severely affected patients

Arousal increased or decreased

Arousal usually normal

Psychotic symptoms

Delusions (if present) fleeting

Delusions (if present) often consistent

Hallucinations common, often visual

Hallucinations infrequent, visual, and auditoryMotor features

Abnormal movements such as tremor or myoclonus common

Abnormal movements often absent

Psychomotor activity increased or decreased

Psychomotor activity usually normalUnderlying physical illness

Symptoms and signs usually present

Symptoms absent

Day and night rhythm

Often disturbed with a marked increase in symptoms during the night

No clear day and night rhythm. Symptoms are more consistent

Vascular dementia

Vascular dementia has an abrupt onset, a fluctuating course, stepwise deterioration, nocturnal confusion, and more frequent focal neurological and clinical signs. The clinical picture can resemble delirium.

Dementia with Lewy bodies

Distinguishing between delirium and dementia with Lewy bodies can be even more problematic. Dementia with Lewy bodies is characterised by marked fluctuating cognition, pronounced variation in attention and alertness, and recurring visual hallucinations, which are typically well formed and detailed. Auditory hallucinations and delusions are often present and fluctuating. There can be spontaneous motor features of parkinsonism, and patients are sensitive to neuroleptic medication. Compared with delirium, dementia with Lewy bodies has a more chronic nature and progression over time.Amnesic syndromes

Amnesic syndromes, such as Korsakoff's syndrome, are characterised by the presence of cognitive deficits occurring in patients with clear consciousness. These deficits affect the short term memory, leading to lack of retention of new information. The immediate recall (for example the digit span) and the long term memory are relatively preserved, and so are many of the other higher cortical functions. These syndromes can coexist with delirium, but in their pure forms you can make the differential diagnosis on clinical grounds.Primary psychotic disorders

It is common to find patients with delirium misdiagnosed as having a primary psychotic illness, for example schizophrenia. The disturbances in sleep and mood along with hallucinations and delusions can be misleading. Psychosis occurs in patients with clear consciousness. Attention and memory are often normal or only minimally impaired, whereas in delirium they are clearly impaired. The mental state abnormalities fluctuate more in delirium, and delusions in particular are less well systematised.Depression

Agitated or retarded depression can resemble delirium. The onset of depression is more gradual and the low mood is typically persistent and worse in the morning. There is also marked anhedonia. Worthlessness and feelings of guilt and profound despair are common and exceed that in delirium. Hallucinations, when they occur, are usually auditory. Concentration and attention are affected. There can be some associated cognitive impairment (also known as pseudodementia) in severe depression. The impaired cognition usually improves with the alleviation of the depressive symptoms, unless there is an underlying dementia.Assessment

Being aware of the possibility of delirium is the key factor in making a diagnosis. Relevant issues in the history are:When was the patient last well?

What are the predisposing factors for delirium in this patient?

If the patient was cognitively impaired before, is there clear evidence of recent deterioration?

Are there any symptoms to suggest some relevant precipitating factors (fever, pain, cough, dysuria, and so on)?

Has any medication been started recently?

Is there any evidence of alcohol and drug misuse?

The clinical assessment method

To diagnose delirium features 1 and 2 and either 3 or 4 must be present.

Acute onset and fluctuating course: onset is hours to days and lucid periods are often in the morning

Inattention: the patient is easily distracted and their attention wanders in conversation

Disorganised thinking: the patient cannot maintain a coherent stream of thought

Altered level of consciousness: the patient is drowsy or overactive

The necessary information is often not reliably available from the patient and therefore it is important to take a collateral history from the patient's family or others. Other sources of information include previous notes and the patient's GP.

Alongside the history it is also essential to assess the patient's mental state including a cognitive assessment. Tools you can use to assess the cognitions include the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Mental Test Score (MTS). There are many reasons for the MMSE and the MTS to be affected and delirium is one of them. You obviously need to do a full physical examination.

Investigations to identify precipitating factors for delirium

Urine dipstickMidstream urine

Blood glucose level

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

Chest x ray

Full blood count

Urea and electrolytes

Cultures of blood or sputum

Blood gases

Drug screen

C-reactive protein

Brain imaging

Thyroid function tests

Liver function tests

Calcium and phosphate

Treatment

Finding and treating the underlying cause is essential. You should presume that all confused patients have delirium until proved otherwise and make a thorough search for the underlying illness(es). Delirium is usually a sign of a poorer prognosis than normal, so treat the relevant disorder vigorously. In about 15% of patients no cause can be found.

Behaviour

Controlling behaviour is an important issue in hospital. It can be difficult to manage a patient's agitation and behavioural changes on an acute ward. You should ideally manage behavioural changes through behavioural means. One way of doing this is by involving family members in the care of the patient. Patients often respond much better to a familiar face. In the absence of family members, perhaps sitters can be used to supervise patients.Every effort should be made to provide patients with consistent nursing staff and to avoid repeated transfers. The staff's approach should be calm and non-confrontational. Hospital staff should always explain what they are doing and why. For example, there is no excuse for moving the patient in and out of bed and adjusting intravenous lines without talking to the patient.

Modifying the environment

Although it is difficult to find research based evidence, it is likely that modifications to the environment can be helpful when managing delirium. Hospitals can make simple adjustments that can make a big difference, for example by providing large clocks, large print calendars, easily readable notice boards, and adjustable lights. You need to encourage self care and, as the patient recovers, participation in activities of daily living.You should avoid physical restraints where possible because they make the patient more anxious and agitated and may contribute to the development of delirium.

Medication

Pharmacological restraints (sedative medication) can be helpful, but prescribe them with caution because there are various troublesome side effects. They can also make the symptoms of delirium worse, prolong the delirium, and worsen mobility.The medical literature regarding which medication to use for the management of behavioural and psychiatric symptoms in delirium is scant. Avoid medication with undesirable side effects, such as cholinergic effects. This means phenothiazines (such as chlorpromazine) are unsuitable.

Antipsychotic medications are often the pharmacological treatment of choice. A randomised controlled trial found that antipsychotics are superior to benzodiazepines. Haloperidol is most frequently recommended because it has few anticholinergic side effects, few active metabolites, and a relatively small likelihood of causing sedation and hypotension. The initial dose should be low, especially for elderly patients. A dose of 1-2 mg every two to four hours as needed (0.25-0.50 mg as needed for elderly patients) can be titrated cautiously to higher doses for patients who continue to be agitated.

You need to monitor side effects and be vigilant for excessive sedation, extrapyramidal side effects, akathesia (motor restlessness), and QT prolongation (with a potential to cause arrhythmias). A baseline ECG is now suggested in the summary of product characteristics for haloperidol and ongoing monitoring of the ECG is determined by the patient's clinical characteristics. You can administer haloperidol orally, intramuscularly, and intravenously. It may cause fewer extrapyramidal side effects if you administer it intravenously.

You should observe sensible basic principles of prescribing and clearly consider:

Target symptomsCareful titration

When you are going to stop it ( time).

This is the "3 T approach." The effect and side effects need to be monitored carefully and the dose of haloperidol slowly reduced and discontinued when symptoms of the delirium subside.

Recent case series and open trials have advocated the use of newer atypical antipsychotics in the management of behavioural and psychiatric symptoms. These include quetiapine, olanzapine, and risperidone. Again, all are recommended at a low dose with titration according to response and side effects.

There is only one small randomised controlled trial that compared risperidone and haloperidol.In this trial there was no significant statistical difference in the efficacy and a suggestion that haloperidol may be associated with more extrapyramidal side effects. You need to weigh this potential advantage against the recent concerns about risperidone and olanzapine and cerebrovascular events when administered to patients with dementia.

Antipsychotics are not appropriate in many patients with delirium, particularly in those with pre-existing dementia (especially Lewy body dementia and Parkinson's disease dementia), patients with stroke, and patients with previous adverse reactions to antipsychotics. Alternatives may be short acting benzodiazepines such as lorazepam. Concerns about their use are related to their potential to oversedate and to cause respiratory depression and disinhibition.

Cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil have been suggested as possible treatments for delirium, primarily because of the supposed underlying cholinergic deficits in delirium. There are only case reports to support this. A randomised controlled trial examined the benefits of donepezil over placebo when given for 14 days before and after total joint replacement surgery in a group of older patients. There was no significant difference in the frequency or duration of postoperative delirium. This negative result may have been because of the:

Small sample size

Relatively young and cognitively intact patient sample

Short run-in period on donepezil.

Benzodiazepines are the first line treatment for delirium tremens and for delirium associated with benzodiazepine withdrawal, and they are also the treatment of choice for alcohol withdrawal. This is because benzodiazepines have a cross tolerability with the GABA system. One of the complications of antipsychotics is that they lower the seizure threshold.

Alcohol withdrawal and associated delirium cannot be adequately treated by providing only a fixed dose regimen for all patients. Treatment should allow for a certain degree of individualisation and should be titrated according to the patient's use and tolerance of alcohol and the intensity of their withdrawal.

Benzodiazepines reduce the risk of seizures and delirium during alcohol withdrawal. Vitamins, particularly thiamines, are an essential part of the treatment. Clonidine, beta blockers, and carbamazepine may reduce selected signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, but they are not recommended as monotherapy.

Medicolegal aspects

Delirious patients can present with tricky ethical and legal problems because some lack the capacity to make decisions about their needs and refuse treatment. In these circumstances it is important to assess the capacity of the patient for that particular issue.To assess whether the patient has the capacity to decide whether to consent to a treatment you should give the relevant information about the proposed treatment, and then determine whether they are able to understand and retain this information for the time that it takes for the decision to be made.

The patient must be able to weigh up the advantages and disadvantages of having the treatment. You must allow the patient to make the decision voluntarily, without any undue pressure.

If the patient has the capacity to make a decision, you must respect their wishes. If the patient lacks the capacity they can be treated under the Mental Capacity Act and the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards. It is important to remember that capacity changes over time, especially with delirium.

As a treating doctor you will need to keep in mind the previous wishes of the patient and the family and act in the best interest of the patient. In these circumstances healthcare professionals can and should provide treatment without consent to patients who lack capacity, if it is considered clinically necessary and in the best interest of the patient.

Sometimes action by healthcare professionals is needed without consent. This would be in emergency situations when there is no time to assess the capacity, for example restraining a violent patient. It is important to remember that on the rare occasions that a case comes to court the doctor will be judged in law as to whether their actions are considered to be good practice by their peers.