Paracetamol overdose: an update on management

د. حسين محمد جمعةاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2010

Introduction

Paracetamol is a useful analgesic that is widely available in the home and in hospitals. It is the drug most commonly used in patients with deliberate self poisoning in the UK, as evidenced by published case series and enquiries to TOXBASE, a national reference database for poisons enquiries.The quoted mortality of paracetamol poisoning in England and Wales between 1989 and 1990 was comparatively low at 0.4% (95% CI 0.38-0.46%). However, in the context of around 41 200 paracetamol related poisonings annually, around 150-200 deaths would be expected to occur annually in England and Wales alone due to paracetamol poisoning.

Most self poisoning with paracetamol occurs in the context of a deliberate, acute ingestion. Many patients act impulsively, are poorly informed of the potential consequences of their actions, and have low suicidal intent. Patients often buy paracetamol for the purpose of self poisoning (in many cases within an hour or so of the act).

Although intentional self poisoning is the most common reason for seeking medical attention, paracetamol poisoning can also arise accidentally, for example when patients increase the dose to toxic levels. Children can take an accidental overdose when their parents miscalculate the dose. Occasionally young children inadvertently swallow paracetamol preparations that are not stored in a safe place.

Elderly patients are prone to accidental paracetamol poisoning if they have an impaired memory and difficulty managing regular dosing regimens, or if they are unable to correctly identify their medications due to impaired vision. Inadvertent paracetamol overdose can also arise if patients overlook the paracetamol content of proprietary cold and flu preparations taken in addition to standard paracetamol tablets.

Paracetamol overdose is responsible for around half of all patients with acute liver failure in the UK. Despite this, it is widely available in the UK both as a prescription drug and as an over the counter product. It is available from pharmacists and other general retailers.

In September 1998, legislation was introduced in the UK to limit the amount of paracetamol or salicylates that could be supplied to patients. Furthermore, the supply of these products became restricted to packaging in blister packs only. It was expected that these legislative amendments might reduce the availability of large amounts of paracetamol, and thereby reduce the incidence of overdose and poisoning.

Data suggested that there had been a reduction in significant paracetamol overdose in the two years after pack size restrictions came into effect in the UK. However, after a longer follow up period there appears to have been no significant effect on paracetamol overdose deaths. Similar restrictions on paracetamol pack size in Ireland have also failed to exert any significant influence on the incidence of paracetamol overdose.

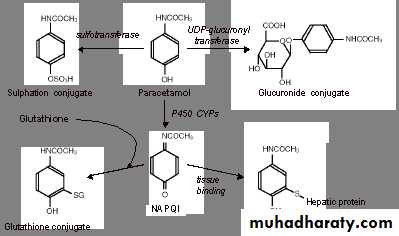

In adults, paracetamol is metabolised through two major pathways in the liver:

glucuronidation and sulphation.Within normal therapeutic paracetamol dosages, a small proportion of paracetamol is metabolised via the cytochrome P450(CYP) 2E1 system, which results in formation of the reactive intermediate product N-acetyl- p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI), which is potentially hepatotoxic.

Under normal circumstances, NAPQI is detoxified by a glutathionine dependent mechanism.

NAPQI concentrations are higher after1. ingestion of larger amounts of paracetamol, particularly in people with

2. induced activity of the P450 system (for example, chronic ethanol intake, carbamazepine, rifampicin, phenytoin) and

3. in people who are deplete in hepatic glutathione (for example, malnourished people, elderly people, patients with HIV infection, recurrent paracetamol overdose).

When NAPQI formation overwhelms glutathione linked clearance mechanisms, it is free to form intracellular covalent bonds that lead to hepatocellular inflammation and ultimately necrosis.

Acetylcysteine readily crosses hepatocyte cell membranes and is deacetylated to cysteine, which can be incorporated into glutathione.

Methionine is metabolised via a number of intermediates, including homocysteine, to cysteine

Key points

Clinical features of paracetamol poisoningAcute paracetamol poisoning is generally asymptomatic. Features can develop, typically more than 12-24 hours after ingestion, and are attributable to hepatotoxicity.

Nausea and vomiting are common, and abdominal pain is a recognised feature accompanied by tenderness on palpation of the right upper quadrant.

Nephrotoxicity is also a recognised feature of acute paracetamol ingestion, which arises through a similar mechanism to hepatotoxicity, accompanied by renal glutathione depletion. Renal dysfunction becomes manifest between days three and nine and, in most cases, it is highly unlikely that significant impairment will occur if hepatic function tests have been satisfactory.

A number of transient metabolic abnormalities can occur, due to altered renal prostaglandin metabolism, including hypokalaemia, hypophosphataemia, and metabolic acidosis.

Paracetamol overdose is a recognised precipitant of acute haemolysis in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.

Key points

TreatmentActivated charcoal:

Reduces absorption of paracetamol if given within one hour of ingestion

Reduces the need for acetylcysteine treatment

Lowers the risk of hepatotoxicity.

You should avoid syrup of ipecacuanha, and gastric lavage is not routinely recommended.

Acetylcysteine, given as an intravenous infusion, is a glutathione precursor, thereby enhancing clearance of toxic paracetamol metabolites (principally NAPQI). Clinical trials have shown that it reduces the risk of liver failure after paracetamol overdose.

Adverse effects are common, including rash, urticaria, bronchospasm, and anaphylactoid reactions. If an anaphylactoid reaction occurs, the infusion should be discontinued temporarily and, rarely, treatment with antihistamines, salbutamol, or corticosteroids may be given. In most cases, the acetylcysteine infusion can be restarted at half the previous rate.

Methionine is an alternative cysteine precursor that has also shown to be effective in lowering the risk of hepatotoxicity after paracetamol ingestion. There is no evidence to suggest an advantage over acetylcysteine, but oral methionine may be useful if access to acetylcysteine treatment might be delayed.

Acute liver failure, transplantation has a limited application. The current King's criteria indicate that patients should be considered for transplantation if arterial pH is <7.3 despite adequate fluid resuscitation, or if the prothrombin time is >100 s, creatinine is >300 µmol/l, and the patient has grade III or IV encephalopathy, these criteria are comparatively insensitive for detecting patients who might die after paracetamol overdose, and further work is needed in this area to develop these criteria.

West Haven Criteria

The severity of hepatic encephalopathy is graded based on the level of impairment of autonomy, changes in consciousness, intellectual function, behavior, and the dependence on therapy.Grade 1 - Trivial lack of awareness; Euphoria or anxiety; Shortened attention span; Impaired performance of addition or subtraction

Grade 2 - Lethargy or apathy; Minimal disorientation for time or place; Subtle personality change; Inappropriate behaviour

Grade 3 - somnolence to semistupor, but responsive to verbal stimuli; Confusion; Gross disorientation

Grade 4 - coma

The maximum recommended daily dose of paracetamol is 4 g.

Paracetamol is one of the most common overdoses in pregnancy and is capable of crossing the placenta. Cytochrome 2E1 does not become active until 14 weeks' gestation and, therefore, the fetus is unable to metabolise paracetamol to NAPQI during this period. Immediate treatment of paracetamol ingestion should be the same as for a non-pregnant female. Neither paracetamol overdose nor acetylcysteine administration appears to have a significant detrimental effect on the developing fetus.You should manage paracetamol poisoning in pregnancy in the standard way. Data are limited, but paracetamol overdose and acetylcysteine do not appear to increase the risk of congenital malformations or other outcome measures

some proponents suggest toxicity should be considered in those who have ingested more than 200 mg/kg, rather than 150 mg/kg in adults

St John's wort can induce the metabolism of paracetamol leading to an increased rate of toxic intermediary formation (NAPQI). Other drugs that induce hepatic microsomal enzymes include:

• Phenytoin

• Phenobarbitone

• Rifampicin

• Carbamazepine

• Chronic ethanol ingestion.

There are strong theoretical reasons why these factors may increase risk, supported by preclinical data, however clinical data are lacking. Chronic alcohol excess induces hepatic enzymes. However, acute intake exerts an inhibitory effect and reduces oxidative metabolism of paracetamol.

This is relevant to paracetamol overdose because chronic background excess alcohol is associated with a worsened prognosis, whereas acute alcohol ingestion at the time of overdose is not associated with a poor outcome. Furthermore, acute alcohol co-ingestion is actually associated with a lower risk of paracetamol hepatotoxicity

Therefore, when considering the need for acetylcysteine treatment a clinical history of acute alcohol ingestion at the time of overdose is insufficient alone to identify the patient as high risk.

Use of methionine is significantly limited by its lack of proved efficacy and high incidence of adverse effects, in particular nausea and vomiting. Acetylcysteine can be given orally, but is also associated with vomiting, and activated oral charcoal can significantly reduce the absorption of both methionine and oral acetylcysteine.

Intravenous acetylcysteine is therefore the treatment of choice.

threshold of toxicity

>150 mg/kg or 12 gOriginal work on paracetamol poisoning in the late 1960s showed that serum concentrations >300 mg/kg at four hours after ingestion were always associated with hepatotoxicity. Serum concentrations less than 120 mg/kg at four hours after ingestion were unlikely to be associated with liver damage.

Later work in the 1970s better defined the relationship between serum paracetamol concentrations, measured between four and 15 hours after ingestion, and the risk of subsequent liver damage.

The best option is to determine serum paracetamol concentration at four hours and determine the need for acetylcysteine after calculating risk by referring to the nomogram. In addition, the following blood tests can help in the clinical assessment of patients with significant paracetamol poisoning:

Plasma glucose

Serum electrolytes including bicarbonate and lactate

Liver biochemistry

Full blood count

Arterial blood gases.

Using syrup of ipecacuanha as an emetic agent has fallen out of favour. It is of unproved efficacy, and its use is complicated by the risk of aspiration of stomach contents and persistent vomiting leading to metabolic disturbance.

the standard treatment thresholds remain the same in the UK for adults and children at 150 mg/kg