1

4th stage

Medicine

Lec-2

Abdullah

Alyouzbaki

20/4/2015

DISEASES OF THE SMALL INTESTINE

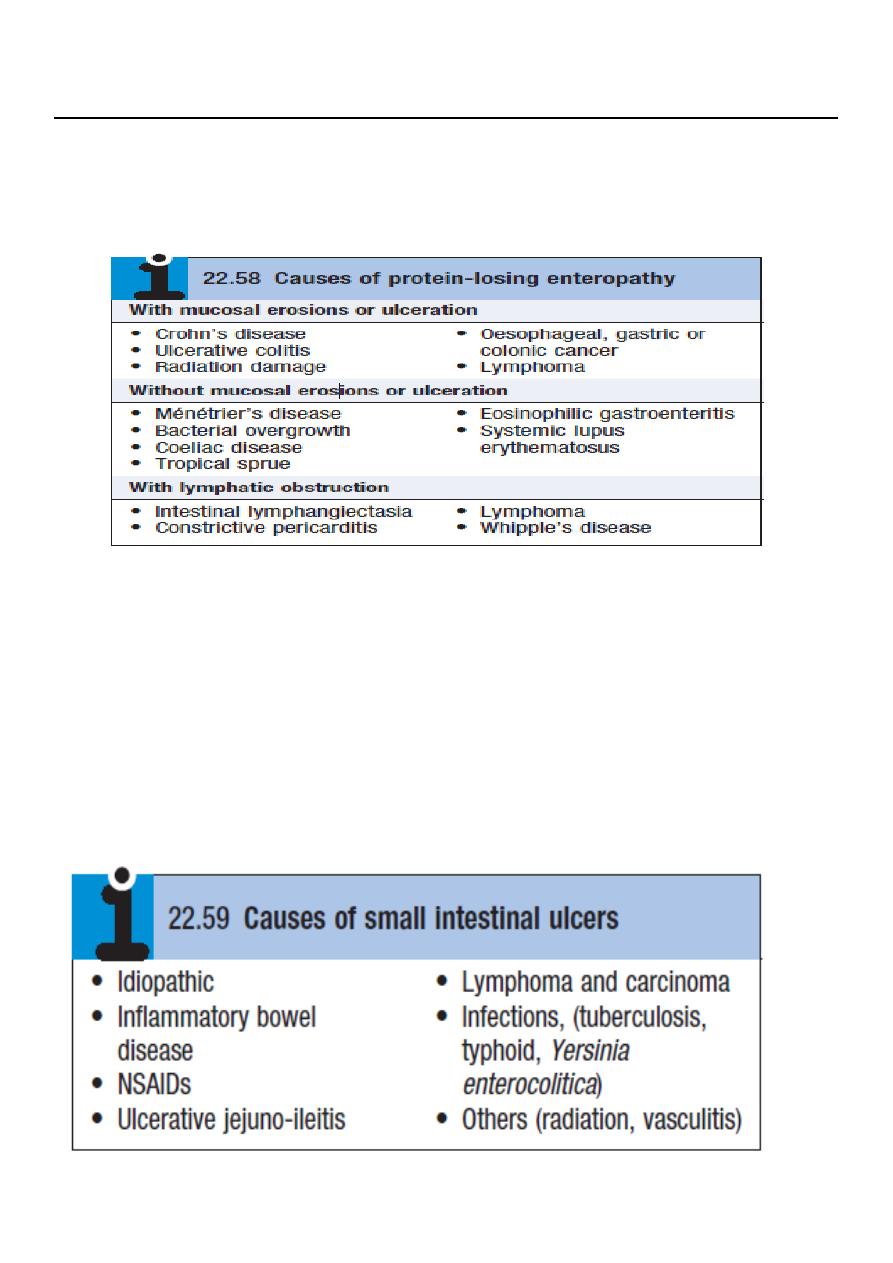

Protein-losing enteropathy

• The diagnosis can be confirmed by measurement of faecal clearance of α1-antitrypsin

or 51Cr-labelled albumin after intravenous injection. Other investigations should be

performed to determine the underlying cause.

• Treatment is that of the underlying disorder, with nutritional support and measures

to control peripheral oedema.

Ulceration of the small intestine

2

Adverse food reactions

• Adverse food reactions are common and are subdivided into food intolerance and

food allergy, the former being much more common.

• In food intolerance, there is an adverse reaction to food which is not immune-

mediated and results from pharmacological (histamine, tyramine or monosodium

glutamate), metabolic (lactase deficiency)or other mechanisms (toxins or chemical

contaminants in food).

Lactose intolerance

• In most populations, enterocyte lactase activity declines throughout childhood.

• In cases of genetically determined (primary) lactase deficiency, jejunal morphology is

normal. ‘Secondary’ lactase deficiency occurs as a consequence of disorders which

damage the jejunal mucosa, such as coeliac disease and viral gastroenteritis.

• Unhydrolysed lactose enters the colon, where bacterial fermentation produces

volatile short-chain fatty acids, hydrogen and carbon dioxide.

Clinical features:

In most people, lactase deficiency is completely asymptomatic.

However, some complain of colicky pain , abdominal distension, increased flatus,

borborygmi and diarrhoea after ingesting milk or milk products.

The lactose hydrogen breath test is a useful non-invasive confirmatory investigation.

• Dietary exclusion of lactose is recommended, although most sufferers are able to

tolerate small amounts of milk without symptoms.

• Addition of commercial lactase preparations to milk has been effective

3

Food allergy

Food allergies are immune-mediated disorders, most commonly due to type I

hypersensitivity reactions with production of IgE antibodies, although type IV delayed

hypersensitivity reactions are also seen.

The most common culprits are peanuts, milk, eggs, soya and shellfish.

Clinical manifestations occur immediately on exposure and range from trivial to life-

threatening or even fatal anaphylaxis

‘gastrointestinal anaphylaxis’ consists of nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and sometimes

cardiovascular and respiratory collapse. Fatal reactions to trace amounts of peanuts

are well documented.s

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of food allergy is difficult .

Skin prick tests.

Double-blind placebo-controlled food challenges are the gold standard, but are

laborious and are not readily available. In many cases, clinical suspicion and trials of

elimination diets are used.

Treatment

• Treatment of proven food allergy consists of detailed patient education and

awareness, strict elimination of the offending antigen.

• Anaphylaxis should be treated as a medical emergency with resuscitation, airway

support and intravenous adrenaline (epinephrine).

4

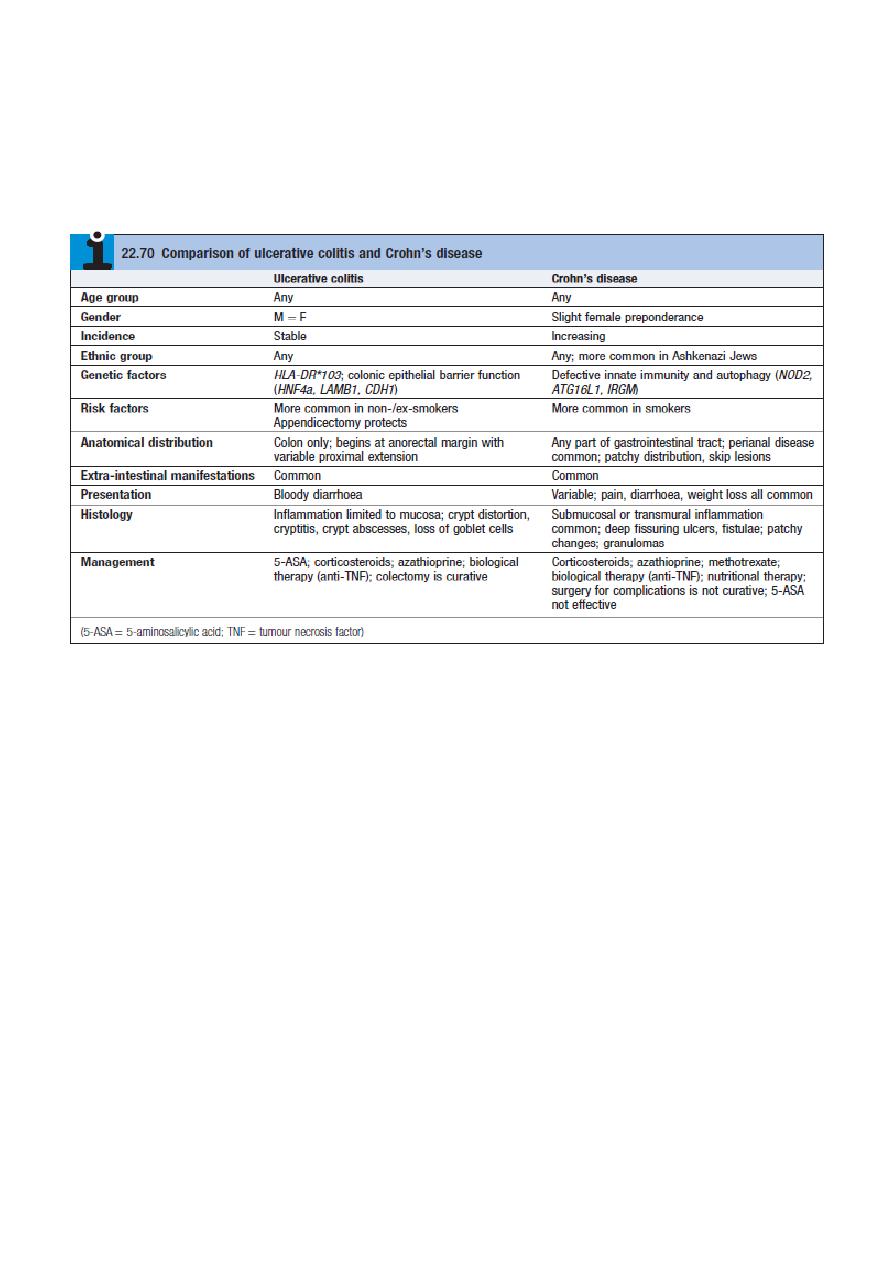

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE IBD

• Both diseases most commonly start in the second and third decades of life, with a

second smaller incidence peak in the seventh decade.

• Life expectancy in patients with IBD is similar to that of the general population.

• Both diseases most commonly start in the second and third decades of life, with a

second smaller incidence peak in the seventh decade.

• Life expectancy in patients with IBD is similar to that of the general population.

Pathophysiology of IBD

Genetic

• Both CD and UC common in Ashkenazi Jews

• 10% have first-degree relative/≥1 close relative with IBD

• High concordance in identical twins (40–50% CD; 20–25% UC)

IBD associated with other inflammatory conditions (esp. ankylosing spondylosis and

psoriasis).

5

Environmental

• UC more common in non-smokers and ex-smokers

• CD more common in smokers (relative risk = 3)

• CD associated with low-residue, high-refined-sugar diet

• Commensal gut microbiota altered (dysbiosis) in CD and UC

• Appendicectomy protects against UC

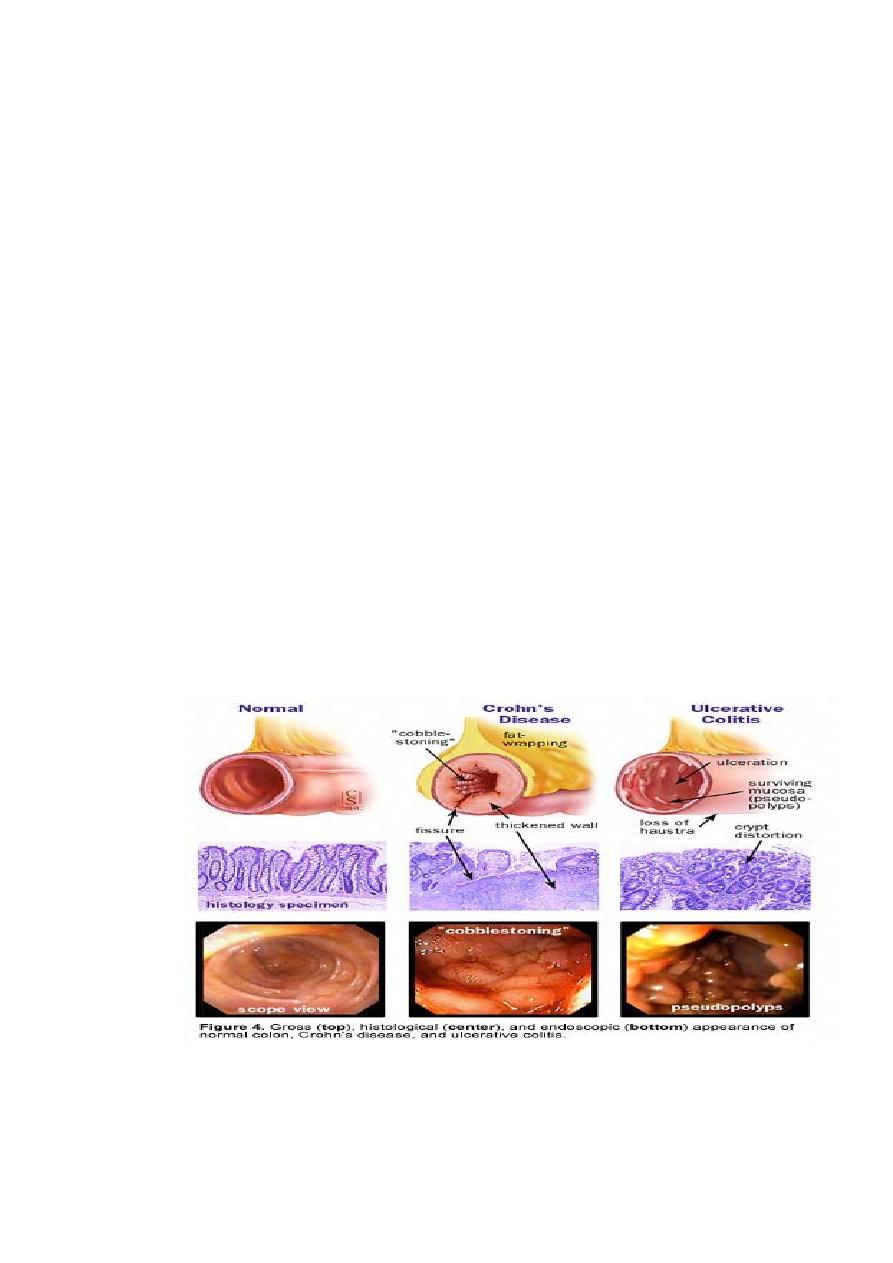

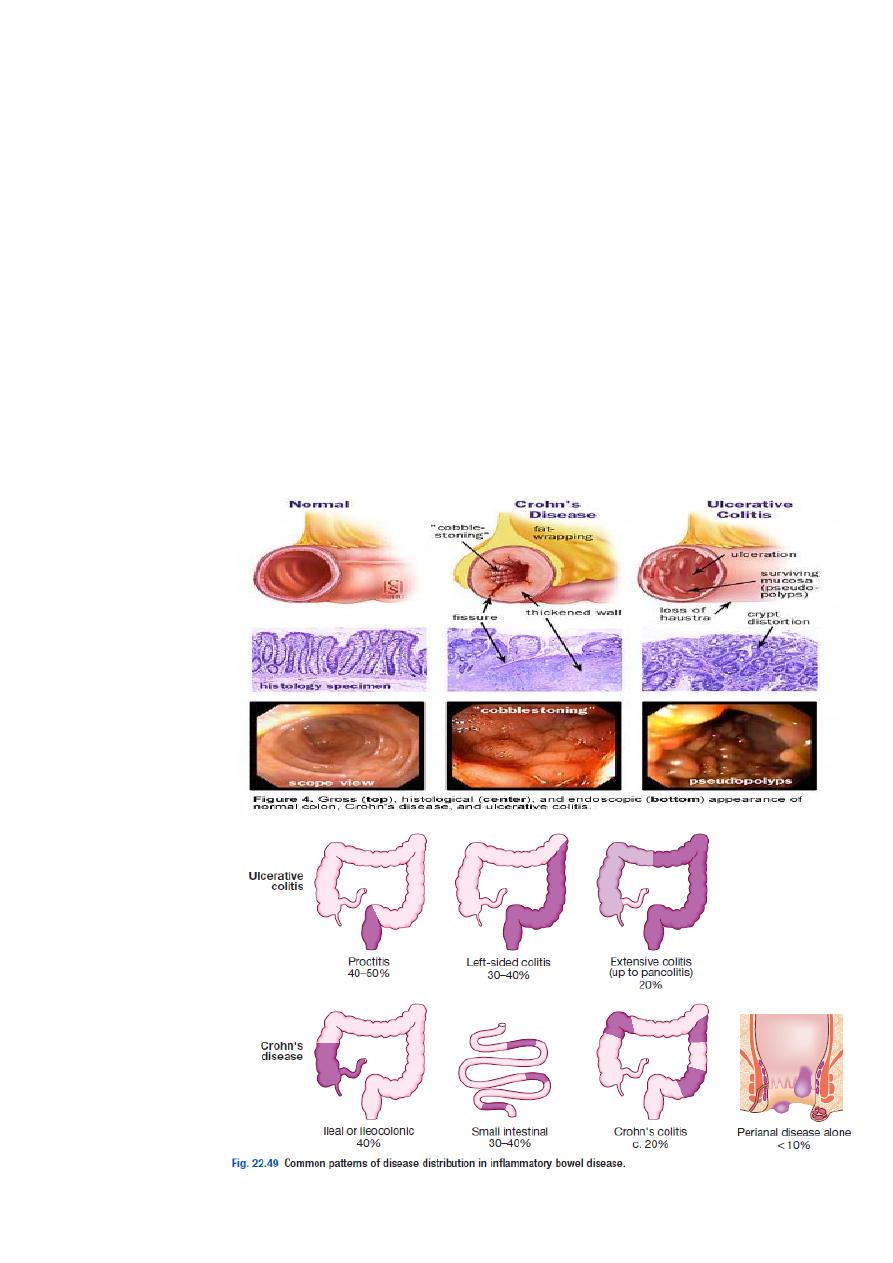

Ulcerative colitis

• Inflammation invariably involves the rectum (proctitis) and spreads proximally in a

continuous manner to involve the entire colon in some cases (pancolitis).

• In long-standing pancolitis, the bowel can become shortened and post-inflammatory

‘pseudopolyps’ develop; these are normal or hypertrophied residual mucosa within

areas of atrophy.

• The inflammatory process is limited to the mucosa and spares the deeper layers of

the bowel wall (Fig. 22.50).

• Both acute and chronic inflammatory cells infiltrate the lamina propria and the

crypts (‘cryptitis’). Crypt abscesses are typical.

6

Crohn’s disease

• The sites most commonly involved are, in order of frequency, the terminal ileum and

right side of colon, colon alone, terminal ileum alone, ileum and jejunum.

• The entire wall of the bowel is edematous and thickened, and there are deep ulcers

which often appear as linear fissures; thus the mucosa between them is described as

‘cobblestone’.

• These may penetrate through the bowel wall to initiate abscesses or fistulae

involving the bowel, bladder, uterus, vagina and skin of the perineum.

• mesenteric lymph nodes are enlarged and the mesentery is thickened.

• Crohn’s disease has a patchy distribution and the inflammatory process is interrupted

by islands of normal mucosa.

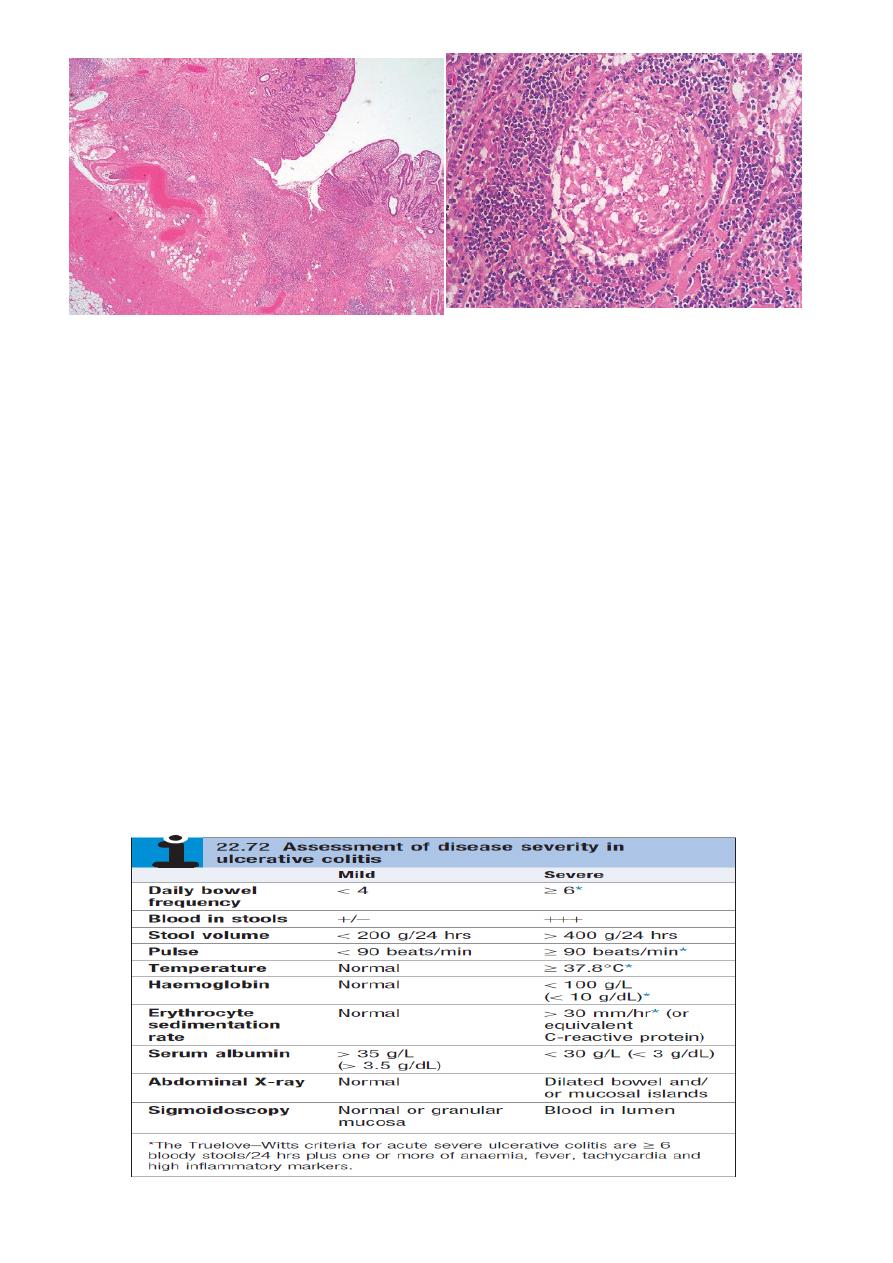

• On histological examination, the bowel wall is thickened with a chronic inflammatory

infiltrate throughout all layers.

7

Histology of Crohn’s disease. A Inflammation is ‘transmural’; there is fissuring ulceration (arrow), with

inflammation

extending into the submucosa (SM). B At higher power, a characteristic non-caseating granuloma is seen.

Clinical features of IBD:

Ulcerative colitis:

• The cardinal symptoms are rectal bleeding with passage of mucus and bloody

diarrhoea. The presentation varies, depending on the site and severity of the disease

, as well as the presence of extra-intestinal manifestations.

• The first attack is usually the most severe and is followed by relapses and remissions.

• Emotional stress, intercurrent infection, gastroenteritis, antibiotics or NSAID therapy

may all provoke a relapse.

8

•

Proctitis

causes rectal bleeding and mucus discharge, accompanied by tenesmus.

Some patients pass frequent, small volume fluid stools, while others pass pellety

stools. Constitutional symptoms do not occur.

Left-sided and extensive colitis

causes bloody diarrhoea with mucus, often with

abdominal cramps. In severe cases, anorexia,malaise, weight loss and abdominal pain

occur, and the patient is toxic, with fever, tachycardia and signs of peritoneal

inflammation

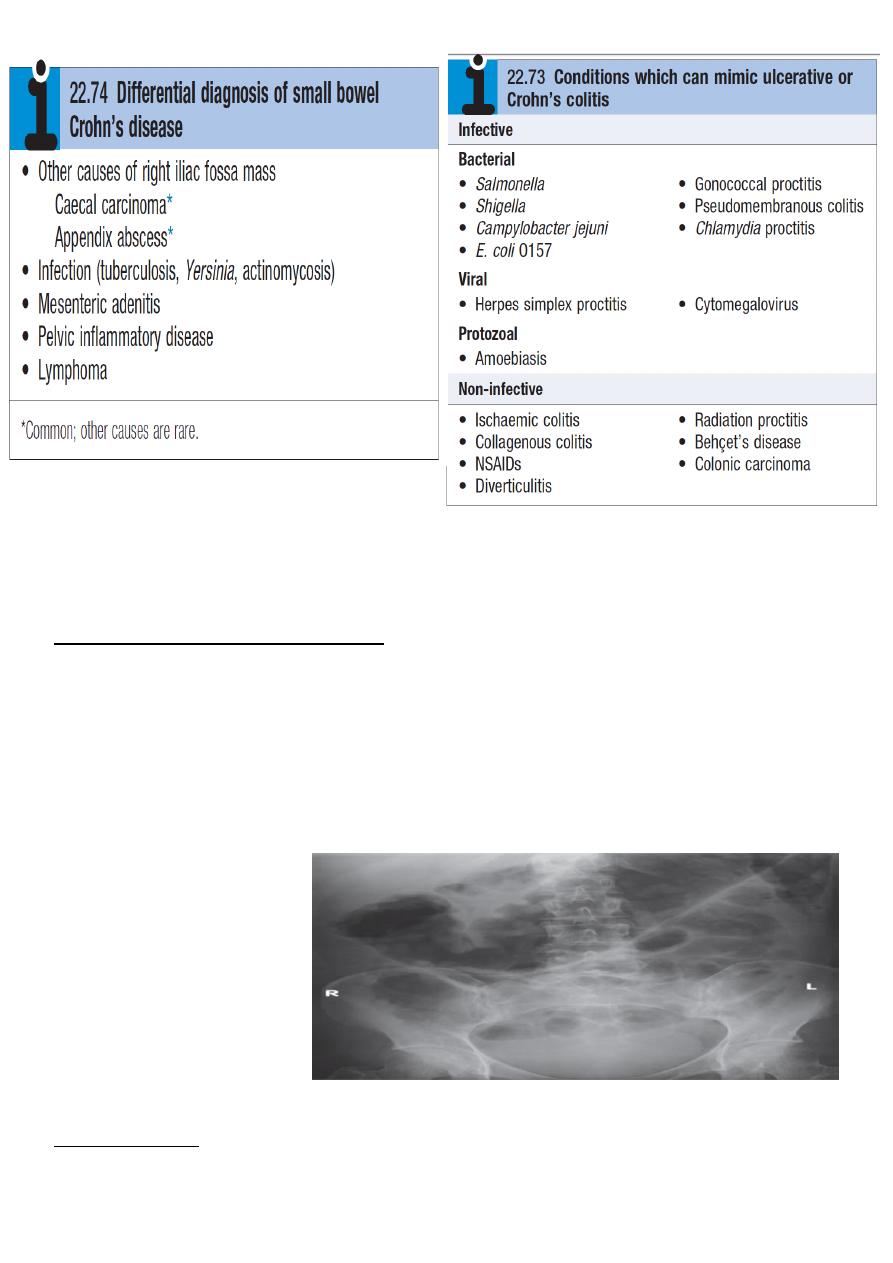

Crohn’s disease:

• The major symptoms are abdominal pain, diarrhoea and weight loss. Ileal Crohn’s

disease may cause sub acute or even acute intestinal obstruction.

• The pain is often associated with diarrhoea, which is usually watery and does not

contain blood or mucus.

• Almost all patients lose weight because they avoid food, since eating provokes pain.

Weight loss may also be due to malabsorption, and some patients present with

features of fat, protein or vitamin deficiencies.

• Crohn’s colitis presents in an identical manner to ulcerative colitis, but rectal sparing

and the presence of perianal disease are features which favour a diagnosis of Crohn’s

disease.

9

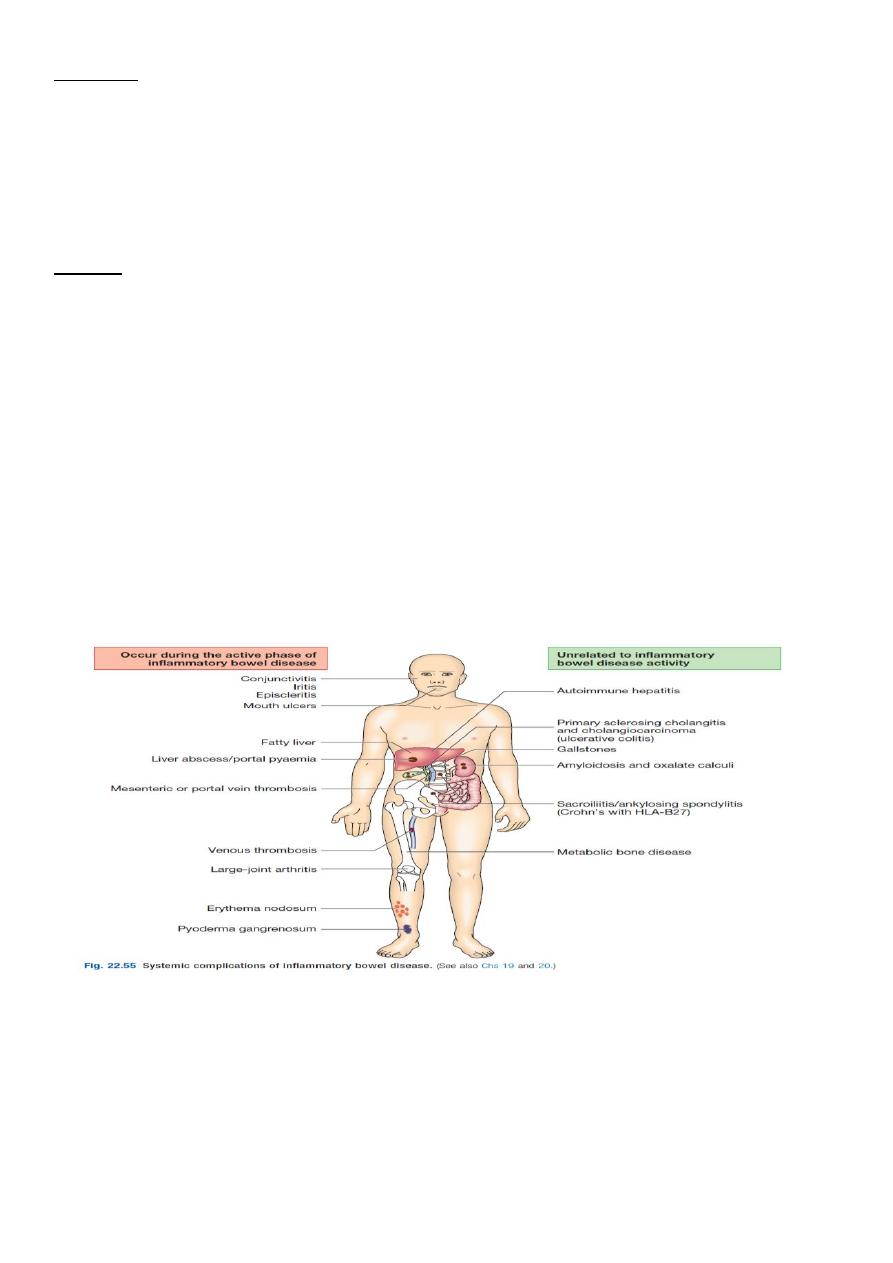

Complications of IBD

Life-threatening colonic inflammation:

• This can occur in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s colitis. In the most extreme cases,

the colon dilates (toxic megacolon) and bacterial toxins pass freely across the

diseased mucosa into the portal and then systemic circulation.

• An abdominal X-ray should be taken daily because, when the transverse colon is

dilated to more than 6 cm, there is a high risk of colonic perforation.

Haemorrhage:

Haemorrhage due to erosion of a major artery is rare but can occur in both conditions.

10

Fistulae:

These are specific to Crohn’s disease. Enteroenteric fistulae can cause diarrhoea and

malabsorption due to blind loop syndrome. Enterovesical fistulation causes recurrent

urinary infections and pneumaturia. An enterovaginal fistula causes a faeculent vaginal

discharge. Fistulation from the bowel may also cause perianal or ischiorectal abscesses,

fissures and fistulae.

Cancer

The risk of dysplasia and cancer increases with the duration and extent of uncontrolled

colonic inflammation.

The risk is particularly high inpatients who have concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis

for unknown reasons. Tumors develop in areas of dysplasia and may be multiple. Patients

with long-standing colitis are therefore entered into surveillance programs beginning 10

years after diagnosis.

If high-grade dysplasia is found, panproctocolectomy is usually recommended because of

the high risk of colon cancer

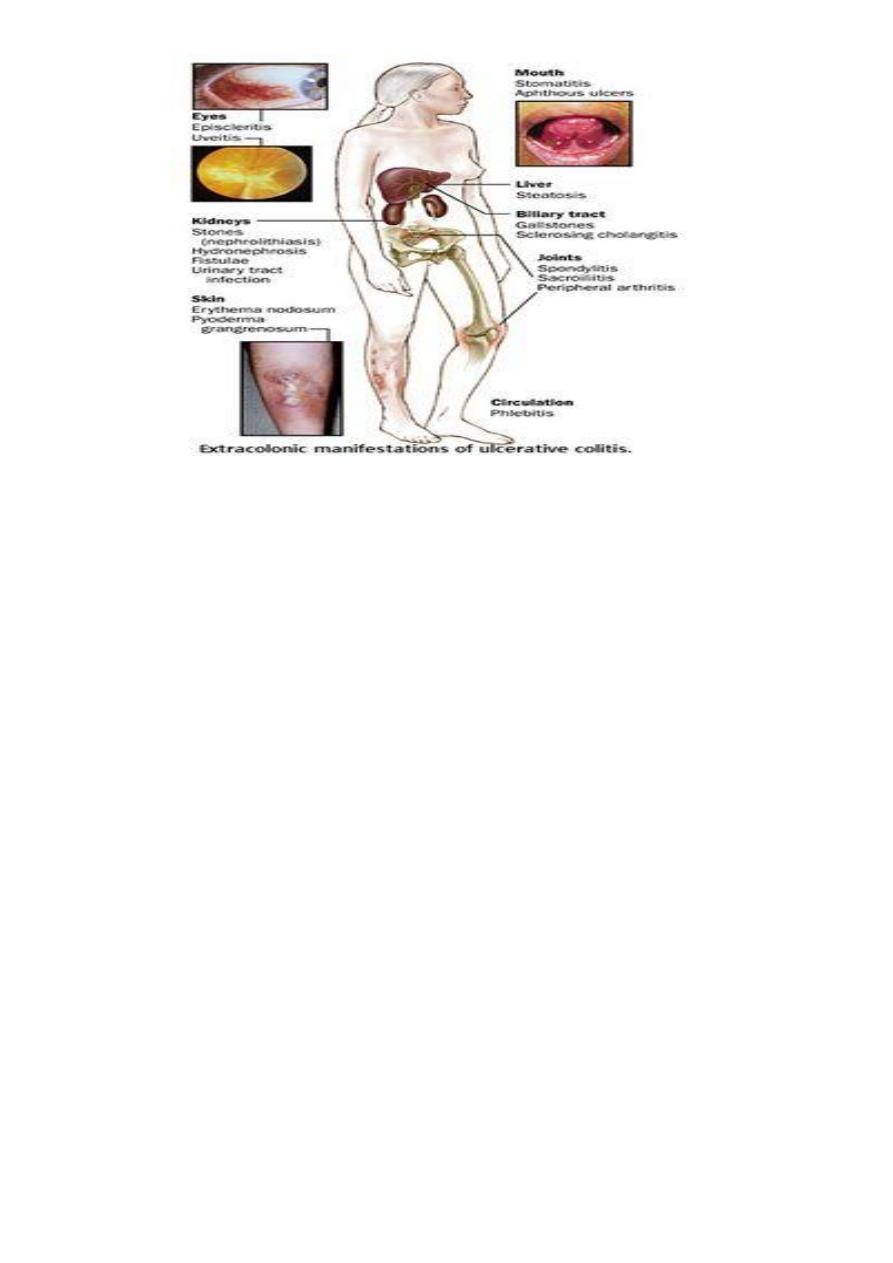

Extra-intestinal complications

11

Investigations

• Investigations are necessary to confirm the diagnosis, define disease distribution and

activity, and identify complications.

• Full blood count may show anaemia resulting from bleeding or malabsorption of iron,

folic acid or vitamin B12.

• Serum albumin concentration falls as a consequence of protein-losing enteropathy,

inflammatory disease or poor nutrition.

• The ESR and CRP are elevated in exacerbations and in response to abscess formation.

• Faecal calproctectin has a high sensitivity for detecting gastrointestinal inflammation

and may be elevated, even when the CRP is normal. It is particularly useful in

distinguishing inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome at

diagnosis, and for subsequent monitoring of disease activity.

• Bacteriology: stool microscopy, culture and examination for Clostridium difficile

toxin or for ova and cysts, blood cultures and serological tests should be performed.

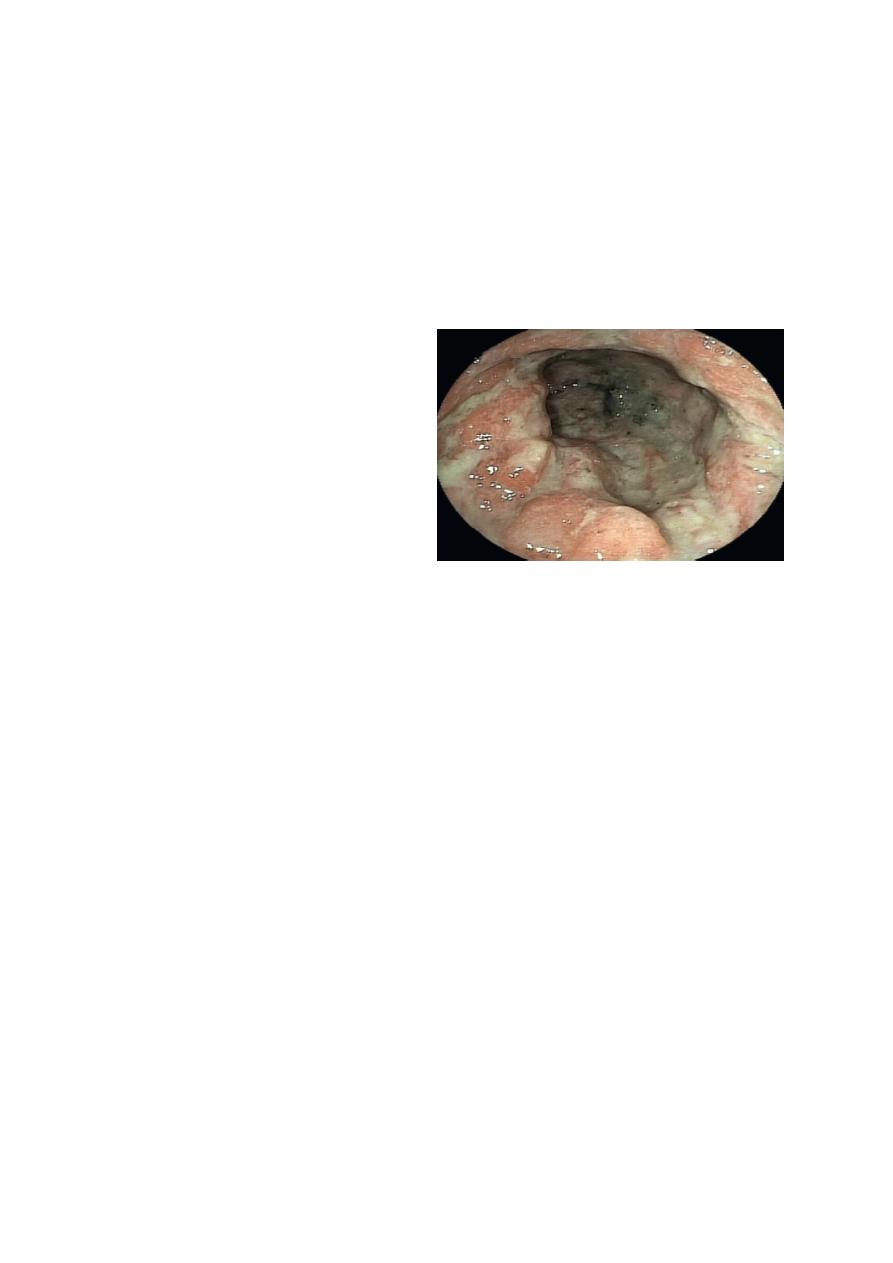

Endoscopy

• Patients who present with diarrhoea plus raised inflammatory markers or alarm

features, such as weight loss, rectal bleeding and anaemia, should undergo

ileocolonoscopy.

12

• Flexible sigmoidoscopy is occasionally performed to make a diagnosis, especially

during acute severe presentations when ileocolonoscopy may confer an

unacceptable risk.

• In ulcerative colitis, there is loss of vascular pattern, granularity, friability and contact

bleeding, with or without ulceration.

• In Crohn’s disease, patchy inflammation, with discrete, deep ulcers, strictures and

perianal disease (fissures, fistulae and skin tags), is typically observed, often with

rectal sparing.

• In Crohn’s disease, wireless capsule

endoscopy ,enteroscopy may be

required.

• All children and most adults with

Crohn’s disease should have upper

gastrointestinal endoscopy

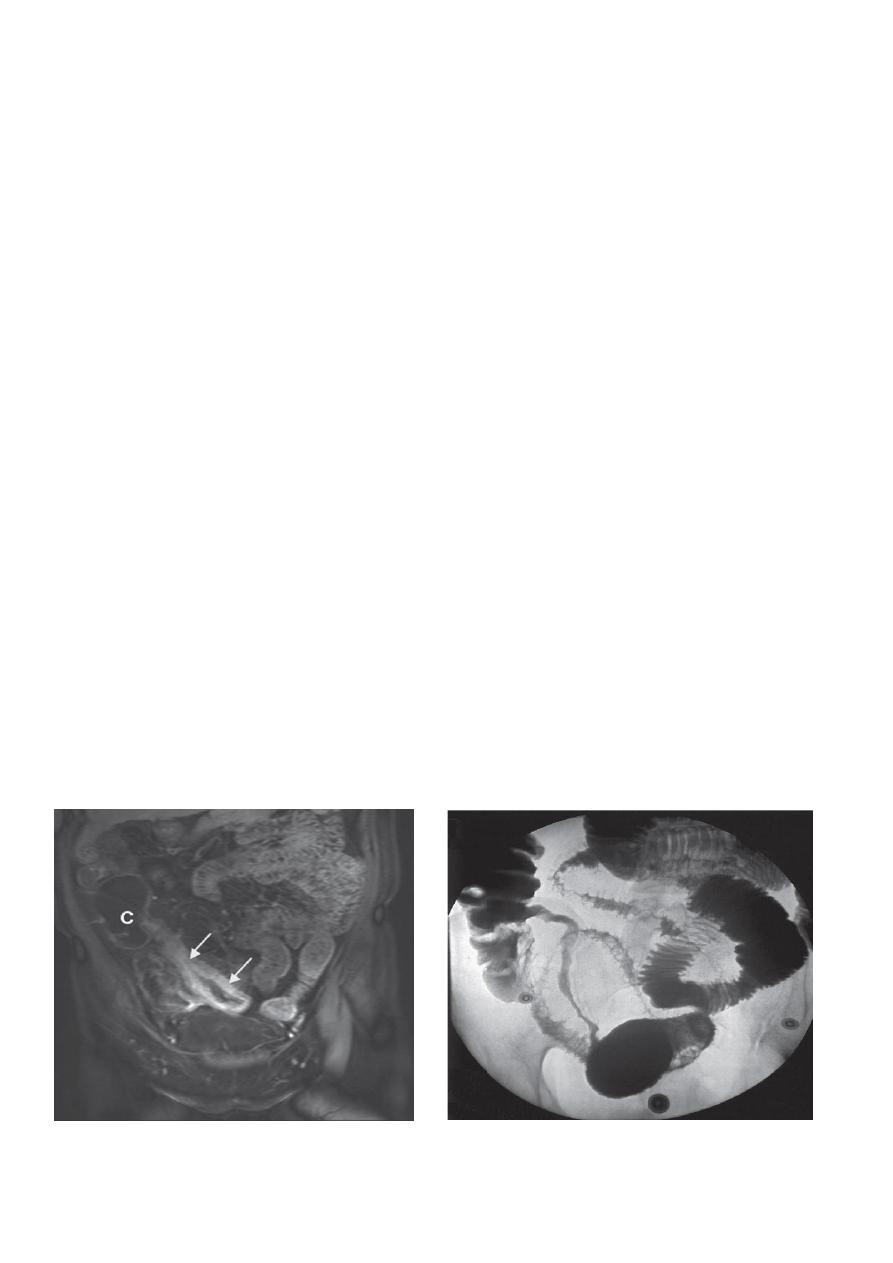

Radiology

• Barium enema is a less sensitive investigation than colonoscopy in patients with

colitis and, where colonoscopy is incomplete, a CT colonogram is preferred.

• Small bowel imaging is essential to complete staging of Crohn’s disease. Traditional

contrast imaging by barium follow-through demonstrates affected areas of the bowel

as narrowed and ulcerated, often with multiple strictures. This has now largely been

replaced by MRI enterography, which is a sensitive way of detecting extra intestinal

manifestations and of assessing pelvic and perineal involvement.

• A plain abdominal X-ray is essential in the management of patients who present with

severe active disease. Dilatation of the colon , mucosal edema (thumb-printing) or

evidence of perforation may be found.

13

Management of IBD

• Although medical therapy plays an important role, optimal management depends on

establishing a multidisciplinary team-based approach involving physicians, surgeons,

radiologists, nurse specialists and dietitians.

The key aims of medical therapy are to:

• treat acute attacks (induce remission)

• prevent relapses (maintain remission)

•prevent bowel damage

• detect dysplasia and prevent carcinoma

• select appropriate patients for surgery.