Medicine

Dr. Ali

“ Chronic Kidney Diseases ”

Total Lec: 47

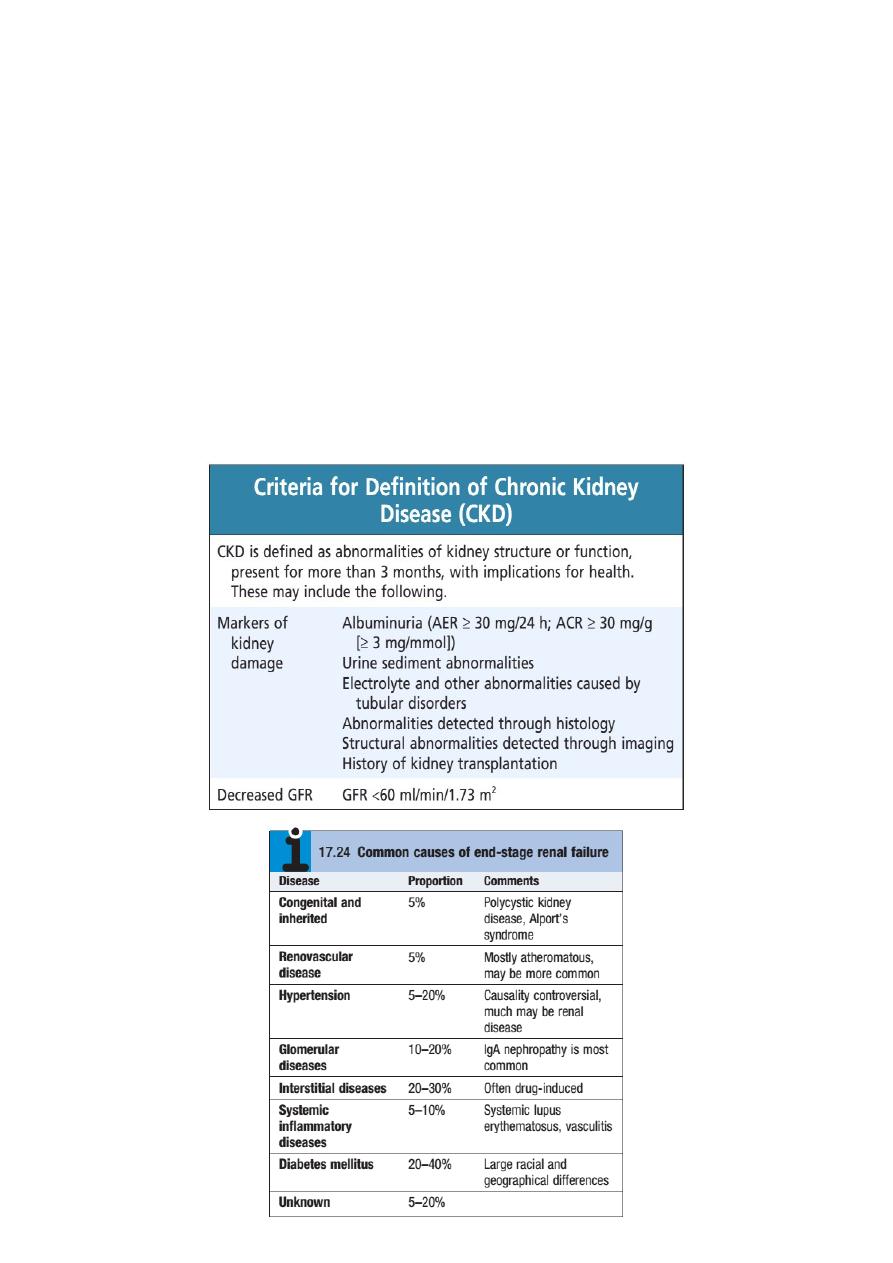

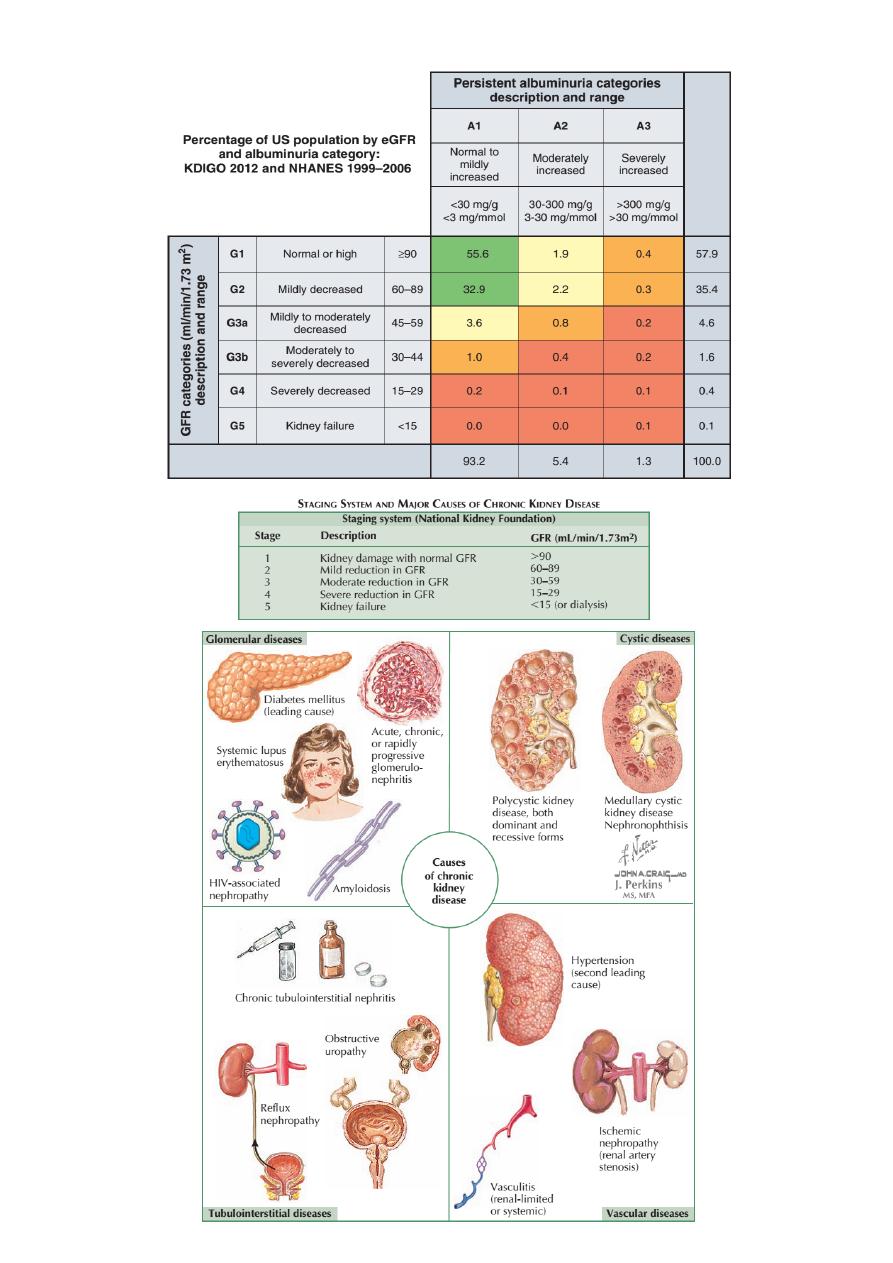

Chronic kidney disease (CKD)

Dr. ALI A. ALLAWI

Nephrologist and Transplant specialist

Internist

CABMS (NEPHROLOGY) , FICMS (NEPHROLOGY) FICMS (MEDICINE)

Chronic kidney disease (CKD)

Previously termed chronic renal failure, refers to an irreversible deterioration

in renal function which usually develops over a period of years. Initially, it is

manifest only as a biochemical abnormality but, eventually, loss of the excretory,

metabolic and endocrine functions of the kidney leads to the clinical symptoms

and signs of renal failure, collectively referred to as uraemia.

of

1

24

of

2

24

Clinical approach to the patient with CKD or any other form of renal disease

History

Particular attention should be paid to:

• Duration of symptoms

• Drug ingestion, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, analgesic and

other medications, and herbal remedies

• Previous medical and surgical history, e.g. previous chemotherapy, multisystem

diseases such as SLE, malaria

• Previous occasions on which urinalysis or measurement of urea and creatinine

might have been performed, e.g. pre-employment or insurance medical

examinations, new patient checks

• Family history of renal disease.

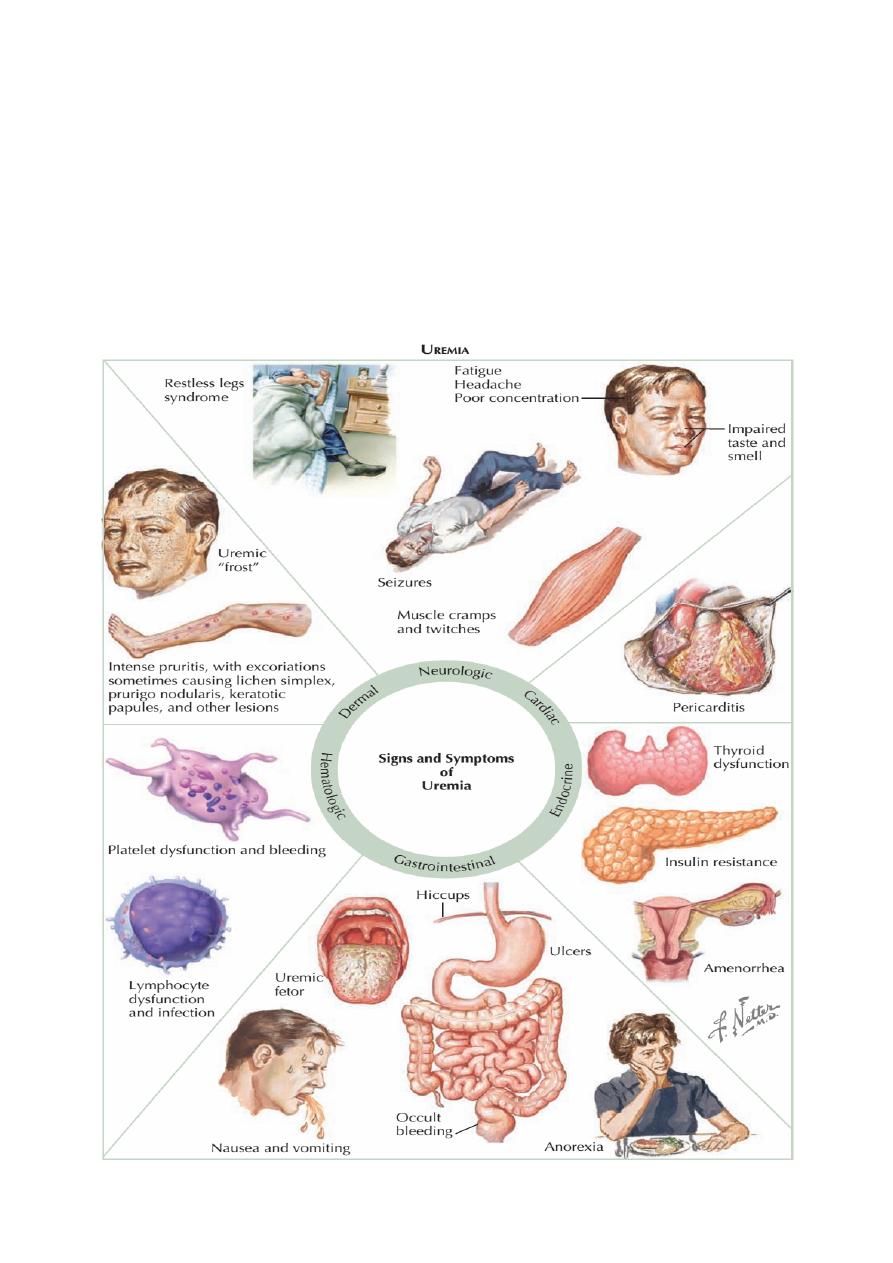

Symptoms

The early stages of CKD are often completely asymptomatic, despite the

accumulation of numerous metabolites. Serum urea and creatinine concentrations

are measured in CKD, since methods for their determination are available and a

rough correlation exists between urea and creatinine concentrations and

symptoms. These substances are, however, in themselves not particularly toxic.

Such metabolites must be products of protein catabolism (since dietary

protein restriction may reverse symptoms associated with CKD) and many of them

must be of relatively small molecular size (since haemodialysis employing

membranes which allow through only relatively small molecules improves

symptoms). Symptoms are common when the serum urea concentration exceeds 40

mmol/L, but many patients develop uraemic symptoms at lower levels of serum

urea. Symptoms include:

• Loss of appetite, Malaise, loss of energy, Insomnia

• Nocturia and polyuria due to impaired concentrating ability

• Itching

• Nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea

• Paraesthesiae due to polyneuropathy

• Restless legs’ syndrome (overwhelming need to frequently alter position of lower

limbs)

• Bone pain due to metabolic bone disease

• Paraesthesiae and tetany due to hypocalcaemia

• Symptoms due to salt and water retention – peripheral or pulmonary oedema

• Symptoms due to anaemia

of

3

24

• Amenorrhoea in women; erectile dysfunction in men. In more advanced uraemia

CKD stage 5, these symptoms become more severe and CNS symptoms are

common:

✴

Mental slowing, clouding of consciousness and seizures, Myoclonic twitching.

✴

Severe depression of glomerular filtration can result in oliguria. This can occur

with either acute kidney injury or in the terminal stages of CKD. However, even

if the GFR is profoundly depressed, failure of tubular reabsorption may lead to

very high urine volumes; the urine output is therefore not a useful guide to

renal function.

of

4

24

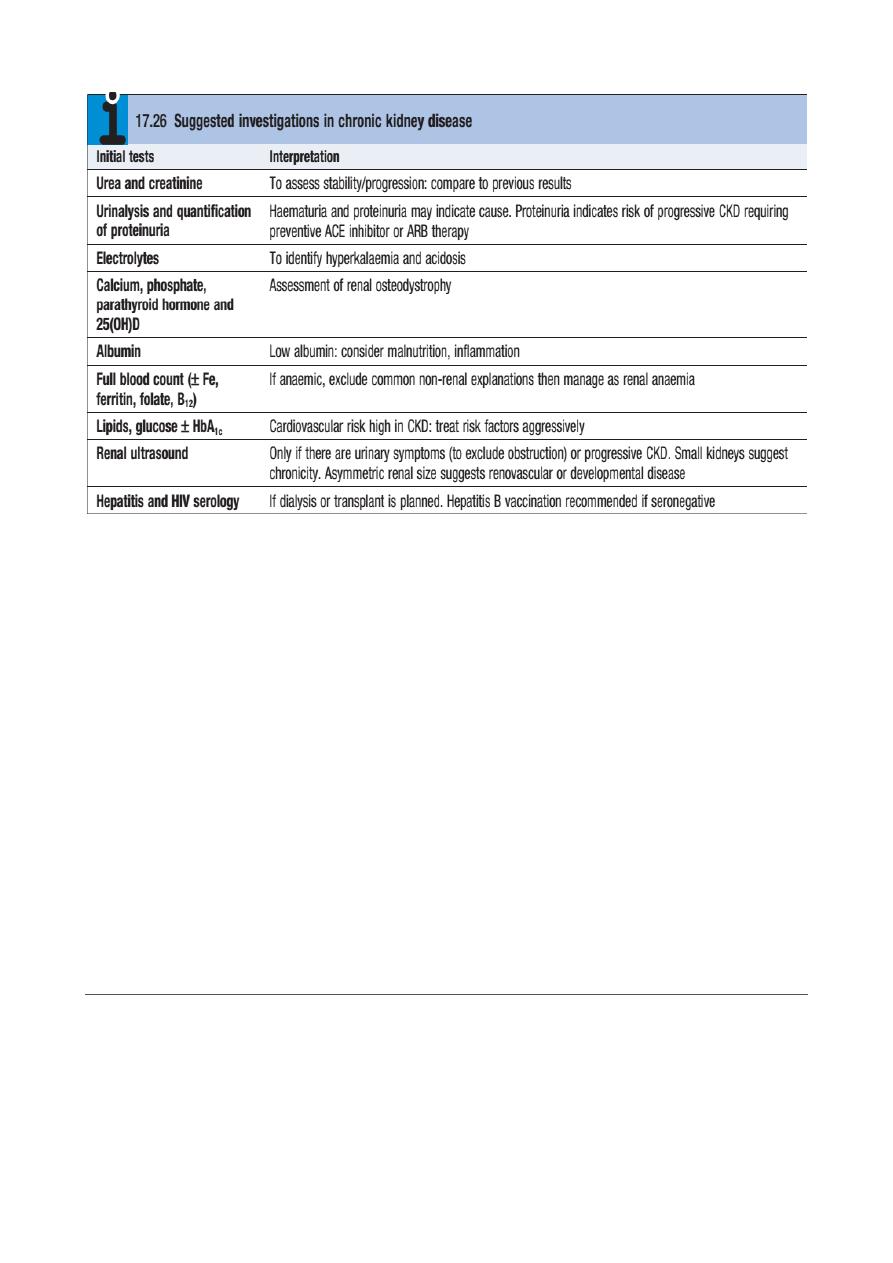

Investigations

The recommended investigations aims are:

•

to identify the underlying cause where possible, since this may influence the

treatment

•

to identify reversible factors that may worsen renal function, such as

hypertension, urinary tract obstruction, nephrotoxic drugs, and salt and water

depletion

•

to screen for complications of CKD, such as anaemia and renal osteodystrophy

•

to screen for cardiovascular risk factors.

Referral to a nephrologist is appropriate for patients with potentially

treatable underlying disease and those who are likely to progress to ESRD.

of

5

24

✦

Kidney Biopsy: In the patient with bilaterally small kidneys, renal biopsy is not

advised because (1) it is technically difficult and has a greater likelihood of

causing bleeding and other adverse consequences, (2( there is usually so much

scarring that the underlying disease may not be apparent, and (3) the window

of opportunity to render disease-specific therapy has passed.

✦

Other contraindications to renal biopsy include uncontrolled hypertension,

active urinary tract infection, bleeding diathesis (including ongoing

anticoagulation), and severe obesity. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy

is the favored approach, but a surgical or laparoscopic approach can be

considered, especially in the patient with a single kidney where direct

visualization and control of bleeding are crucial.

✦

In the CKD patient in whom a kidney biopsy is indicated (e.g., suspicion of a

concomitant or superimposed active process such as interstitial nephritis or in

the face of accelerated loss of GFR), the bleeding time should be measured,

and if increased, desmopressin should be administered immediately prior to

the procedure.

Complications of chronic kidney disease

A. Anaemia

Several factors have been implicated:

• Erythropoietin deficiency (the most significant)

of

6

24

• Toxic effects of uraemia on marrow precursor cells and retaining of Bone

marrow toxins in CKD

• Reduced red cell survival

• Bone marrow fibrosis secondary to hyperparathyroidism

• Haematinic deficiency – iron, vitamin B12, folate

• Reduced intake, absorption and utilisation of dietary iron

• Increased red-cell destruction, Abnormal red-cell membranes causing increased

osmotic fragility . Increased red-cell destruction may occur during haemodialysis

owing to mechanical, oxidant and thermal damage.

• Increased blood loss – occult gastrointestinal bleeding, blood sampling, blood

loss during haemodialysis, capillary fragility, or because of platelet dysfunction

• ACE inhibitors (may cause anaemia in CKD, probably by interfering with the

control of endogenous erythropoietin release).

of

7

24

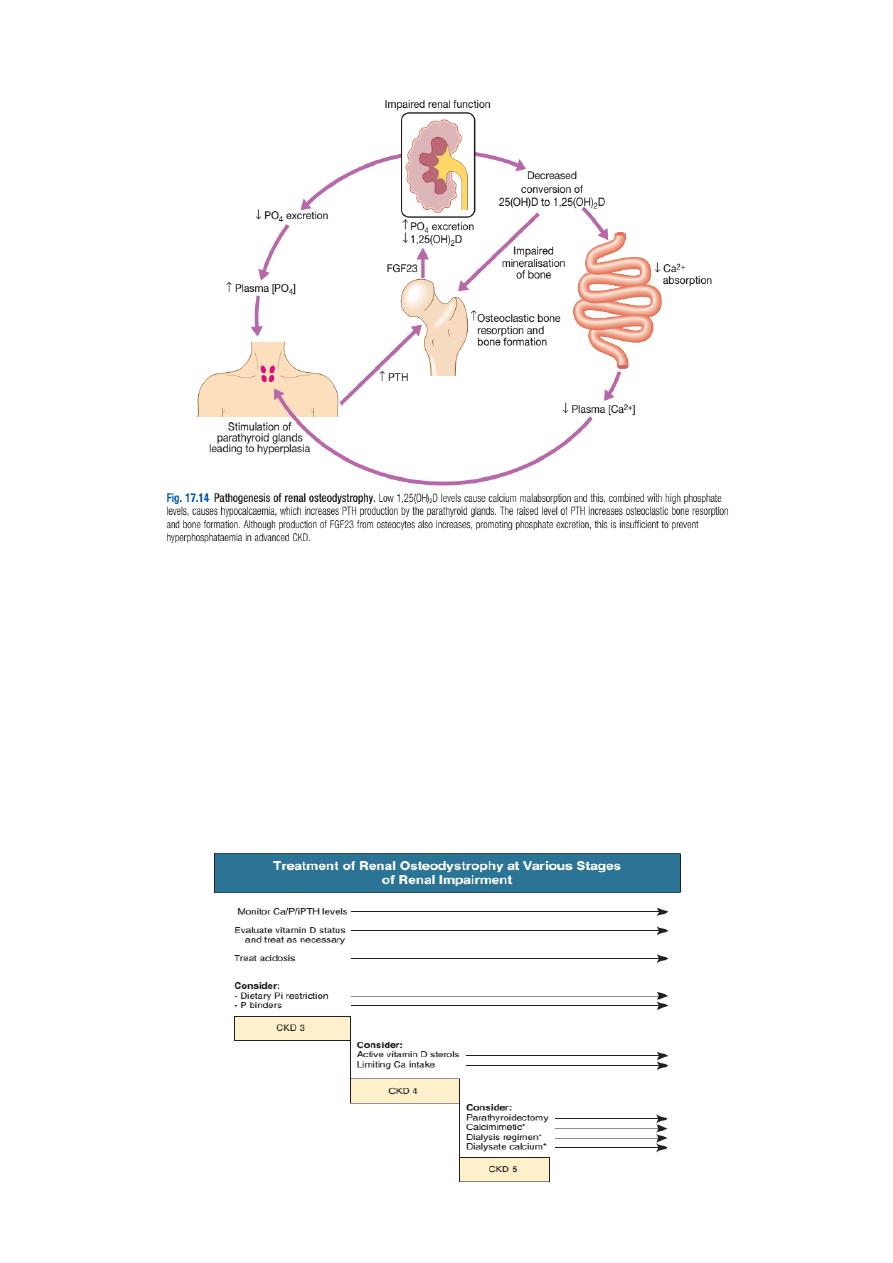

B. Chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD)

Disturbances of mineral metabolism are common. The spectrum of disorders

includes abnormal concentrations of serum calcium, phosphate, and magnesium

and disorders of parathyroid hormone (PTH), fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23),

and vitamin D metabolism.

These abnormalities as well as other factors related to the uremic state affect

the skeleton and result in the complex disorders of bone known as renal

osteodystrophy; it is now recommended that this term be used exclusively to

define the bone disease associated with CKD. The clinical, biochemical, and

imaging abnormalities heretofore identified as correlates of renal osteodystrophy

should be defined more broadly as a clinical entity or syndrome called chronic

kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). The spectrum of skeletal

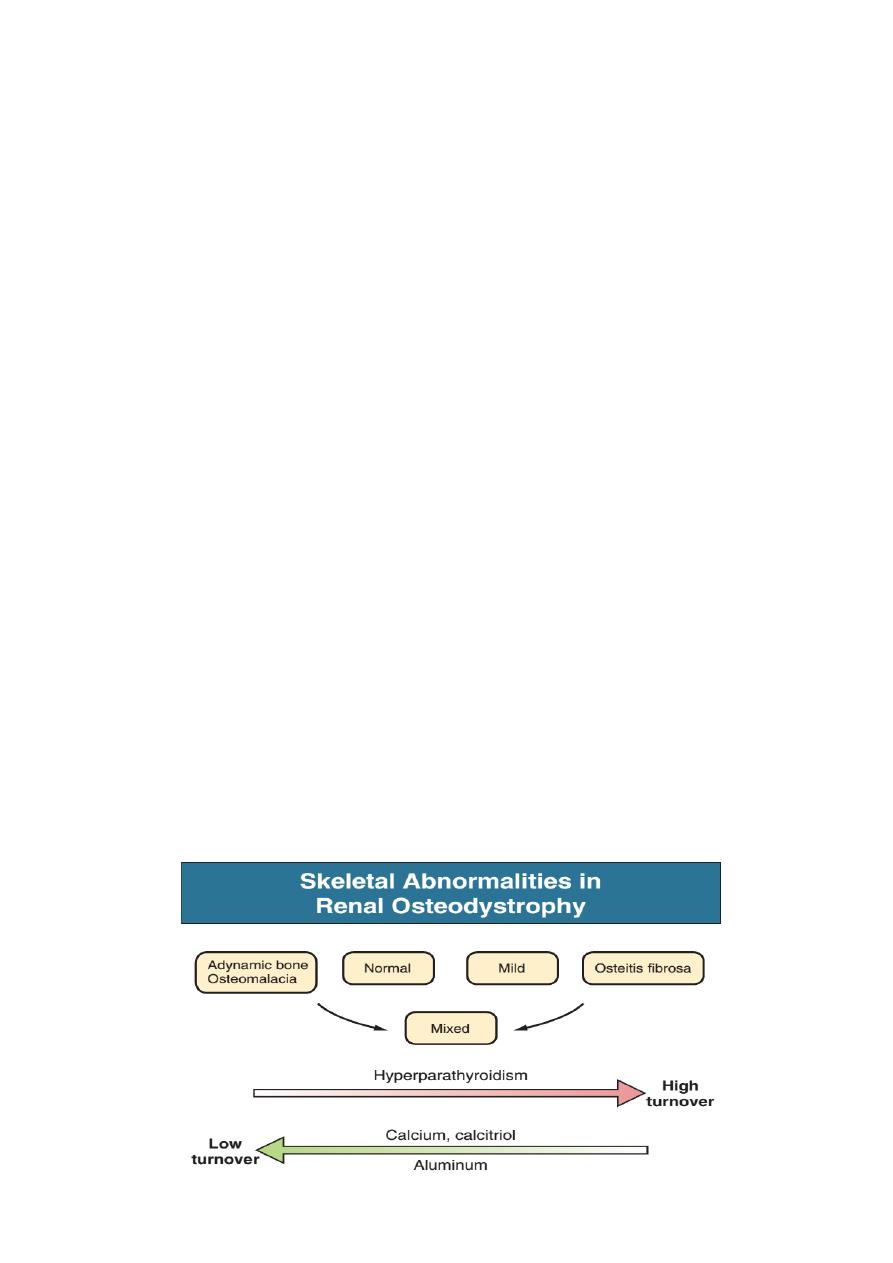

abnormalities seen in renal osteodystrophy includes the following :

‣

Osteitis fibrosa, a manifestation of hyperparathyroidism characterized by

increased osteoclast and osteoblast activity, peritrabecular fibrosis, and

increased bone turnover.

‣

Osteomalacia, a manifestation of defective mineralization of

newly formed osteoid most often caused by aluminum deposition;

bone turnover is decreased.

‣

Adynamic bone disease (ABD), a condition characterized by

abnormally low bone turnover in which both bone formation and resorption are

depressed (in the absence of aluminium bone disease or overtreatment with

vitamin D) is also seen.

‣

Osteopenia or osteoporosis.

‣

Combinations of these abnormalities termed mixed renal

osteodystrophy.

‣

Other abnormalities with skeletal manifestations (e.g., chronic

acidosis, β2-microglobulin amyloidosis).

of

8

24

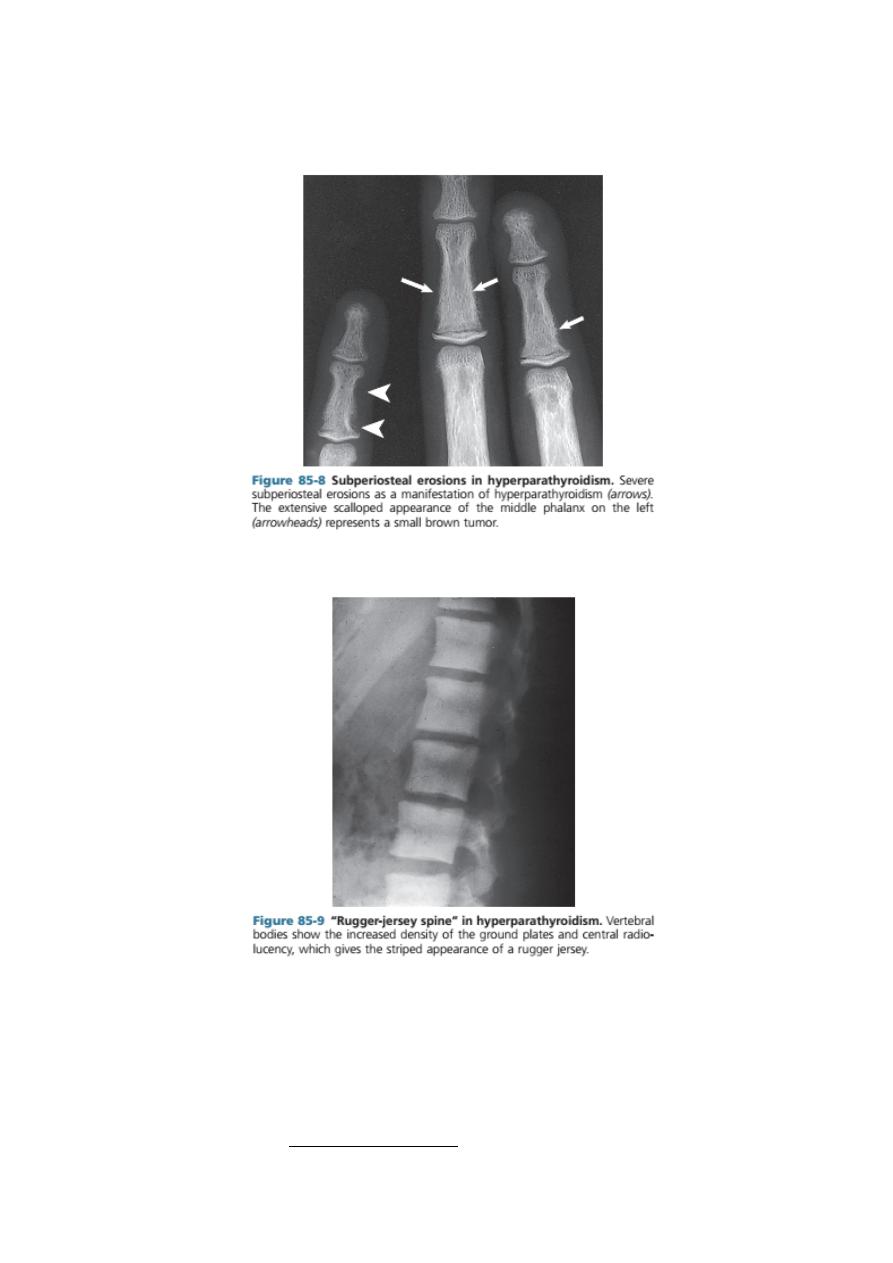

Radiologically,

(

a part of menial and bon disorder )

- Digital subperiosteal erosions and ‘pepperpot skull’ are seen.

- Longstanding secondary hyperparathyroidism ultimately leads to hyperplasia of

the glands with autonomous or tertiary hyperparathyroidism in which

hypercalcaemia is present. Serum alkaline phosphatase concentration is raised in

both secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism. Longstanding parathyroid

hormone excess is also thought to cause increased bone density (osteosclerosis)

seen particularly in the spine where alternating bands of sclerotic and porotic

bone give rise to a characteristic ‘rugger jersey’ appearance on X-ray.

of

9

24

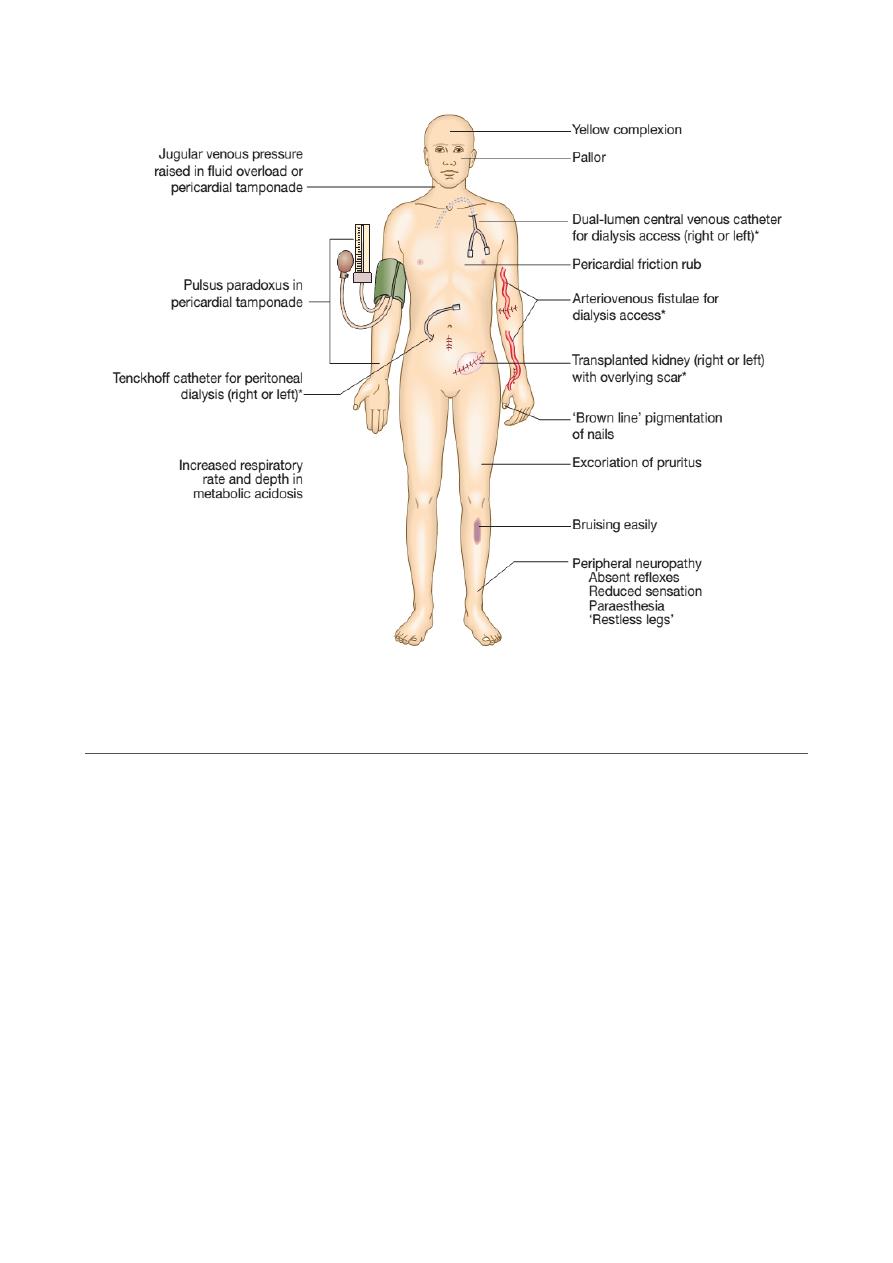

C. Immune dysfunction

Cellular and humoral immunity is impaired in advanced CKD and there is

increased susceptibility to infections, the second most common cause of death in

dialysis patients, after cardiovascular disease.

D. Haematological

- There is an increased bleeding tendency in advanced CKD, which manifests as

cutaneous ecchymoses and mucosal bleeds.

of

10

24

- Platelet function is impaired and bleeding time prolonged. Adequate dialysis

partially corrects the bleeding tendency in those with severe uraemia, but these

patients are at significantly increased risk of complications from all

anticoagulants, including those that are required during dialysis.

- Anaemia is common and is due in part to reduced erythropoietin production.

Haemoglobin can be as low as 5-7 g/dL in CKD stage 5, although it is often less

severe or absent in patients with polycystic kidney disease.

E. Electrolyte abnormalities

Patients with CKD often develop electrolyte abnormalities like hyperkalemia

and metabolic acidosis. Fluid retention is common in advanced CKD , Conversely,

some patients with tubulointerstitial disease can develop ‘saltwasting’ disease

and may require a high sodium and water intake, including supplements of sodium

salts, to prevent fluid depletion and worsening of renal function. Acidosis is

common. Although it is usually asymptomatic, it may be associated with increased

tissue catabolism and decreased protein synthesis, and may exacerbate bone

disease and the rate of decline in renal function.

F. Neurological and muscle function

- Generalised myopathy may occur due to a combination of poor nutrition,

hyperparathyroidism, vitamin D deficiency and disorders of electrolyte

metabolism.

- Muscle cramps are common.

- The ‘restless leg syndrome’, in which the patient’s legs are jumpy during the

night, may be troublesome. Symptoms may improve with the correction of

anaemia by erythropoietin. Clonazepam is sometimes useful. Renal

transplantation cures the problem.

- Both sensory and motor neuropathy can arise, presenting as paraesthesia and

foot drop, respectively, but appear late during the course of CKD. They are now

unusual, given the widespread availability of RRT; if present, they can often

improve once dialysis is established.

- Asterixis, fits, tremor and myoclonus are features of severe uraemia.

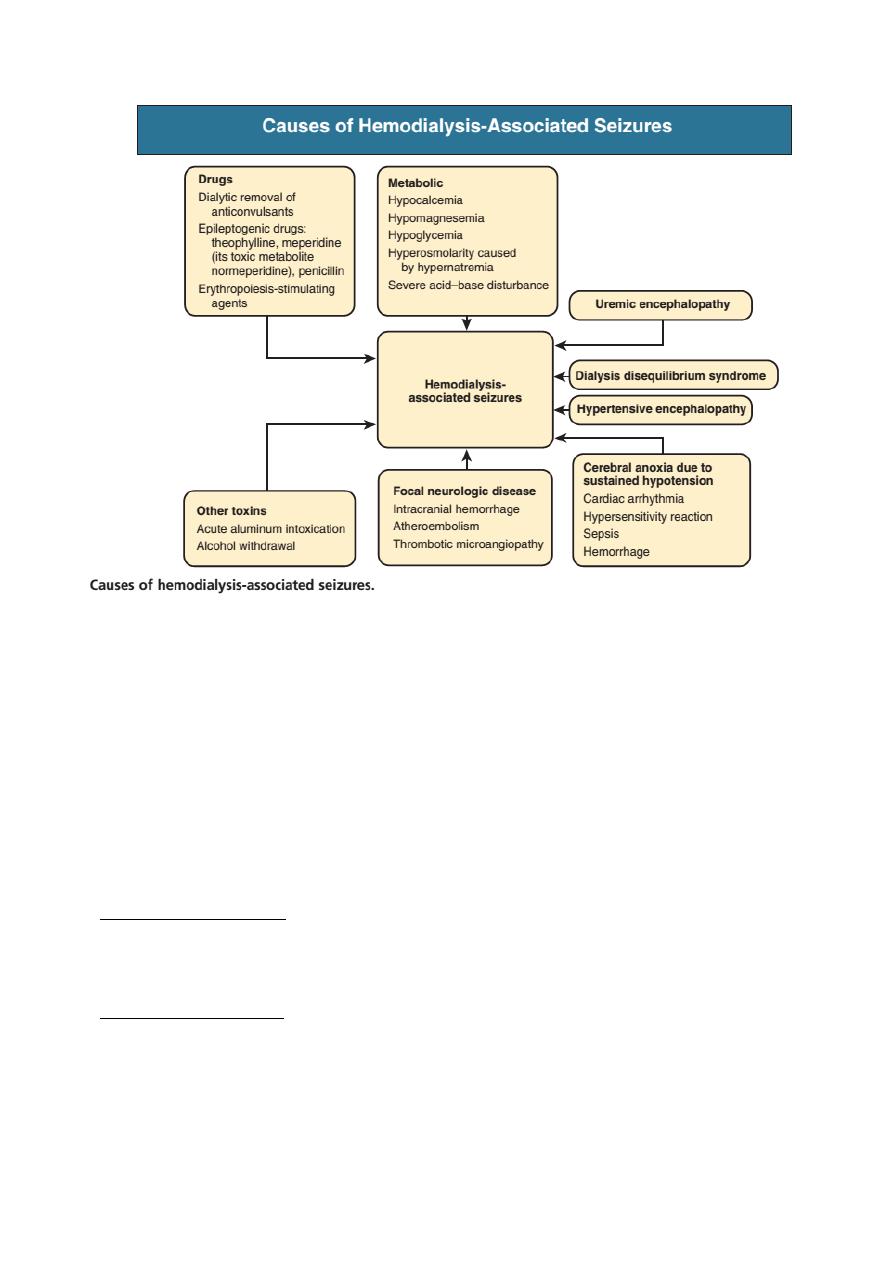

- Dialysis Disequilibrium Syndrome: Rapid correction of severe uraemia by

haemodialysis leads to dialysis disequilibrium owing to osmotic cerebral

swelling.This can be avoided by correcting uraemia gradually by use of

volumetric-controlled hemodialysis machines, bicarbonate dialysate, sodium

modeling, earlier recognition of uremic states, and stepped initiation of dialysis

(short initial treatment times with lower blood pump speeds). In addition, short

and more frequent dialysis treatments are recommended with use of small

surface area dialyzers and reduced blood flow rates.

- Seizures: convulsions in a uraemic patient are much more commonly due to other

causes such as accelerated hypertension, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

or drug accumulation.

of

11

24

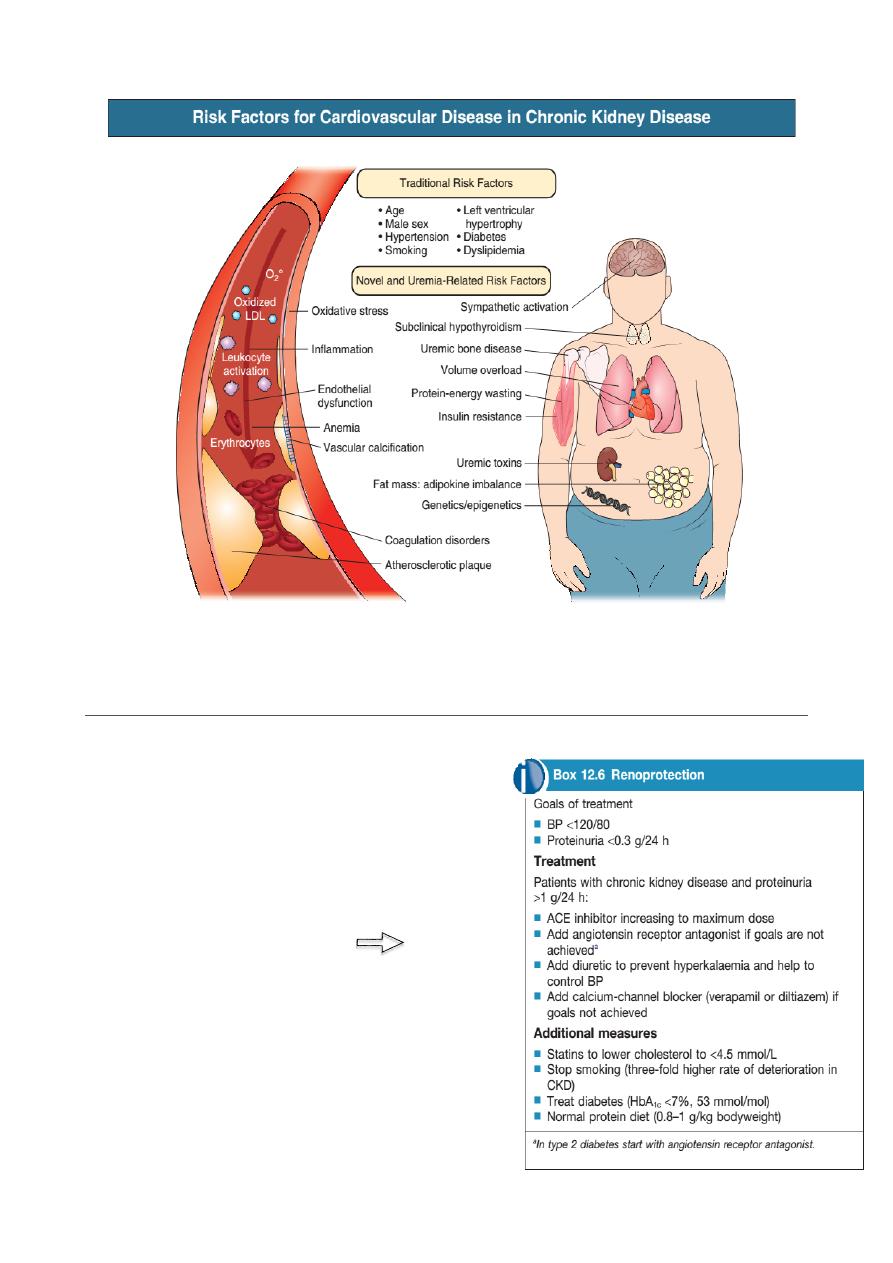

G. Cardiovascular disease

‣ The risk of cardiovascular disease is substantially increased in patients with CKD

stage 3 or worse (GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and those with proteinuria or

microalbuminuria.

‣ Left ventricular hypertrophy may occur, secondary to hypertension, and may

account for the increased risk of sudden death (presumed to be caused by

dysrhythmias) in this patient group.

‣ Pericarditis may complicate untreated or inadequately treated ESRD and cause

pericardial tamponade or constrictive pericarditis. This is common and occurs in

two clinical settings:

‣ Uraemic pericarditis is a feature of severe, pre-terminal uraemia or of

underdialysis. Haemorrhagic pericardial effusion and atrial arrhythmias are often

associated. There is a danger of pericardial tamponade, and anticoagulants

should be used with caution. Pericarditis usually resolves with intensive dialysis.

‣ Dialysis pericarditis occurs as a result of an intercurrent illness or surgery in a

patient receiving apparently adequate dialysis.

of

12

24

Management of chronic kidney disease

The underlying cause of CKD should be

treated aggressively wherever possible.

1. Renoprotection

The multidrug approach to chronic

nephropathies has been formalized in an

international protocol beside:

of

13

24

2. Correction of complications

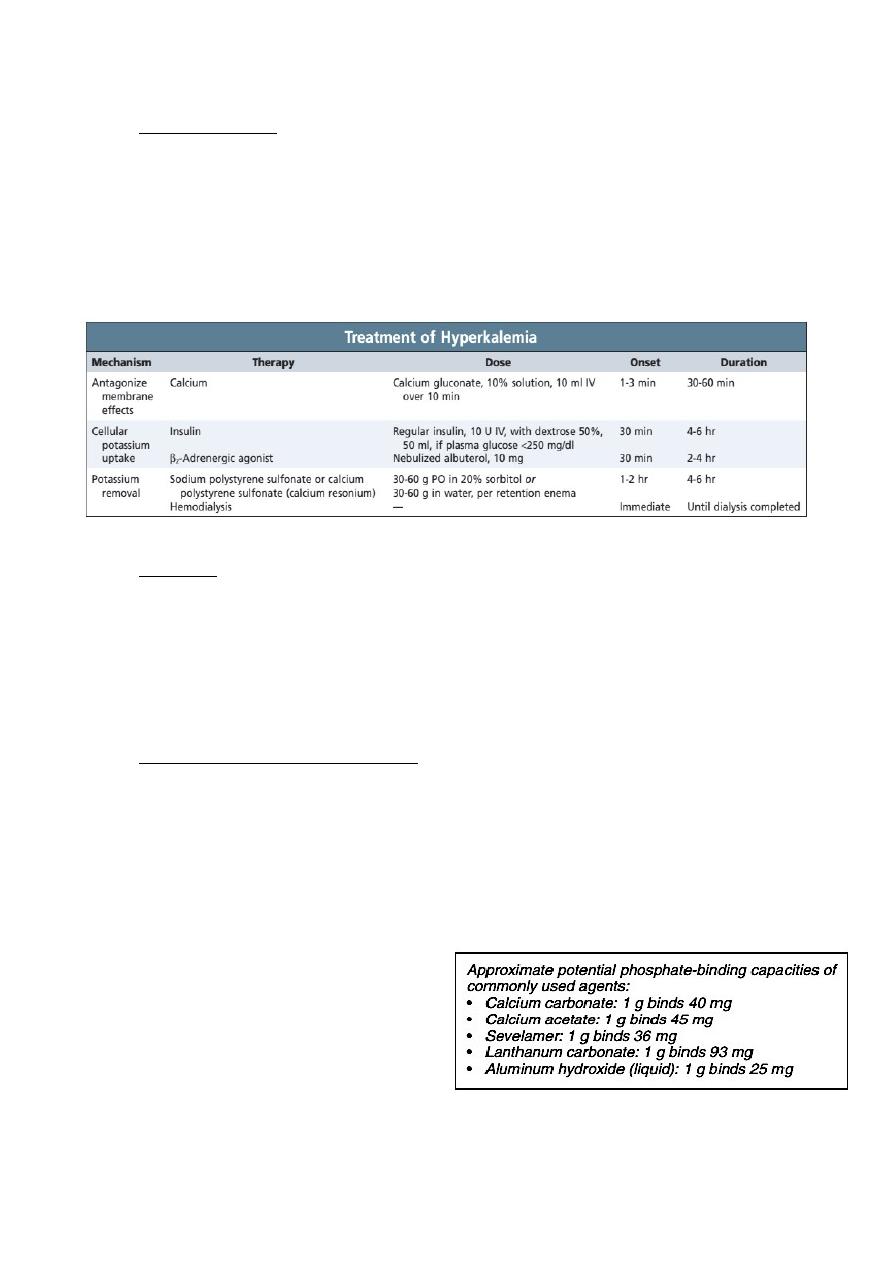

Hyperkalaemia : Hyperkalaemia often responds to dietary restriction of

potassium intake. Drugs like ACEi/ARBs and others which cause potassium

retention should be stopped. Occasionally, it may be necessary to prescribe ion-

exchange resins to remove potassium in the gastrointestinal tract such as sodium

polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) or calcium polystyrene sulfonate (calcium

resonium). Emergency treatment of severe hyperkalaemia is mandatory in CKD

patients.

Acidosis: Correction of acidosis helps to correct hyperkalaemia in CKD, and

may also decrease muscle catabolism. The plasma bicarbonate should be

maintained above 22 mmol/L by giving sodium bicarbonate supplements (starting

dose of 1 g 3 times daily, increasing as required). If the increased sodium intake

induces hypertension or oedema, calcium carbonate (up to 3 g daily) may be used

as an alternative, since this has the advantage of also binding dietary phosphate.

Renal bone disease (CKD MBD): treatment should be initiated with

‣ Active vitamin D metabolites (either 1αhydroxyvitamin D or 1,25

dihydroxyvitamin D) in patients who are found to have hypocalcaemia or serum

PTH levels more than twice the upper limit of normal. The dose should be

adjusted to try to reduce PTH levels to between 2 and 4 times the upper limit of

normal to avoid over suppression of bone turnover and adynamic bone disease,

but care must be exercised in order to avoid hypercalcaemia.

‣ Hypocalcaemia and hyperphosphataemia should be treated aggressively.

‣ Hyperphosphataemia should be treated

by dietary restriction of foods with high

phosphate content (milk, cheese, eggs

and protein rich foods) and by the use

of phosphate binding drugs. Various

drugs are available, including calcium

carbonate, aluminium hydroxide,

lanthanum carbonate and polymerbased phosphate binders such as sevelamer.

The aim is to maintain serum phosphate values at 1.8 mmol/L (5.6 mg/dL) or

of

14

24

below if possible, but many of these drugs are difficult to take and compliance

may be a problem.

‣ Parathyroidectomy may be required for the treatment of tertiary

hyperparathyroidism. An alternative is to employ calcimimetic agents, such as

cinacalcet, which bind to the calcium sensing receptor and reduce PTH secretion.

They have a place if parathyroidectomy is unsuccessful or not possible.

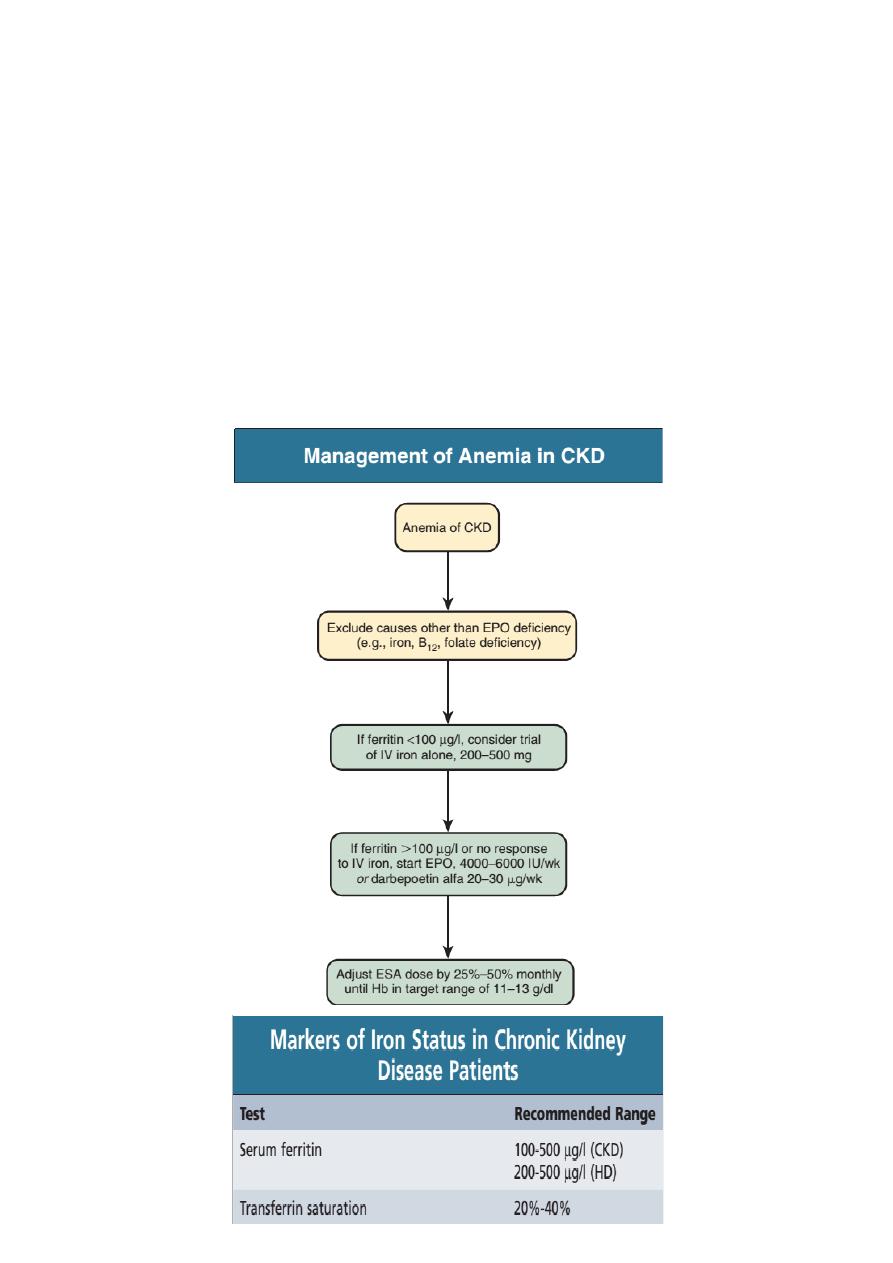

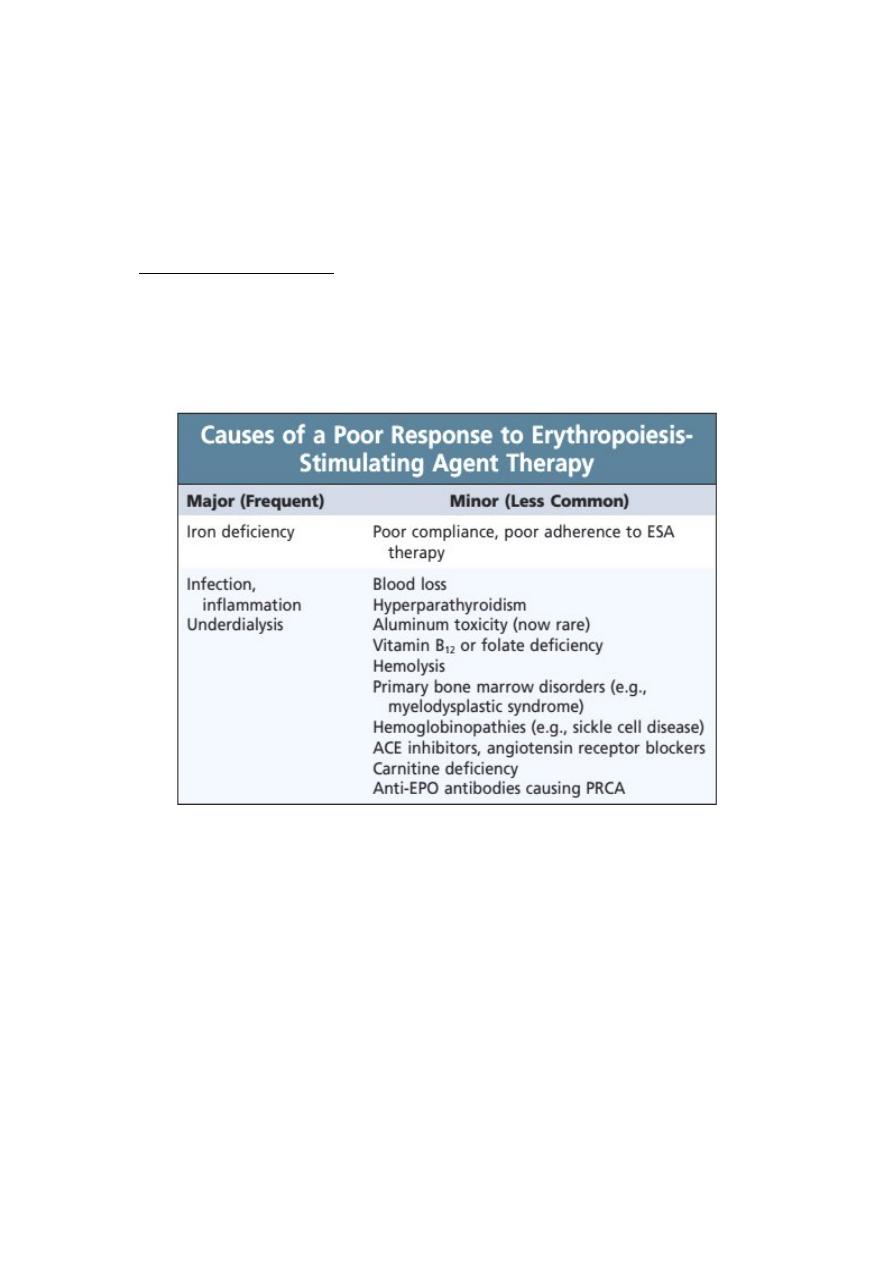

Treatment of Anemia

1. Correction of iron deficiency anemia

2. Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents such as Epoetin alpha (Eprex) , Epoetin

Beta (Mircera), Darbepoetin and Peginesatide (previously called Hematide) is an

EPO-mimetic peptide.

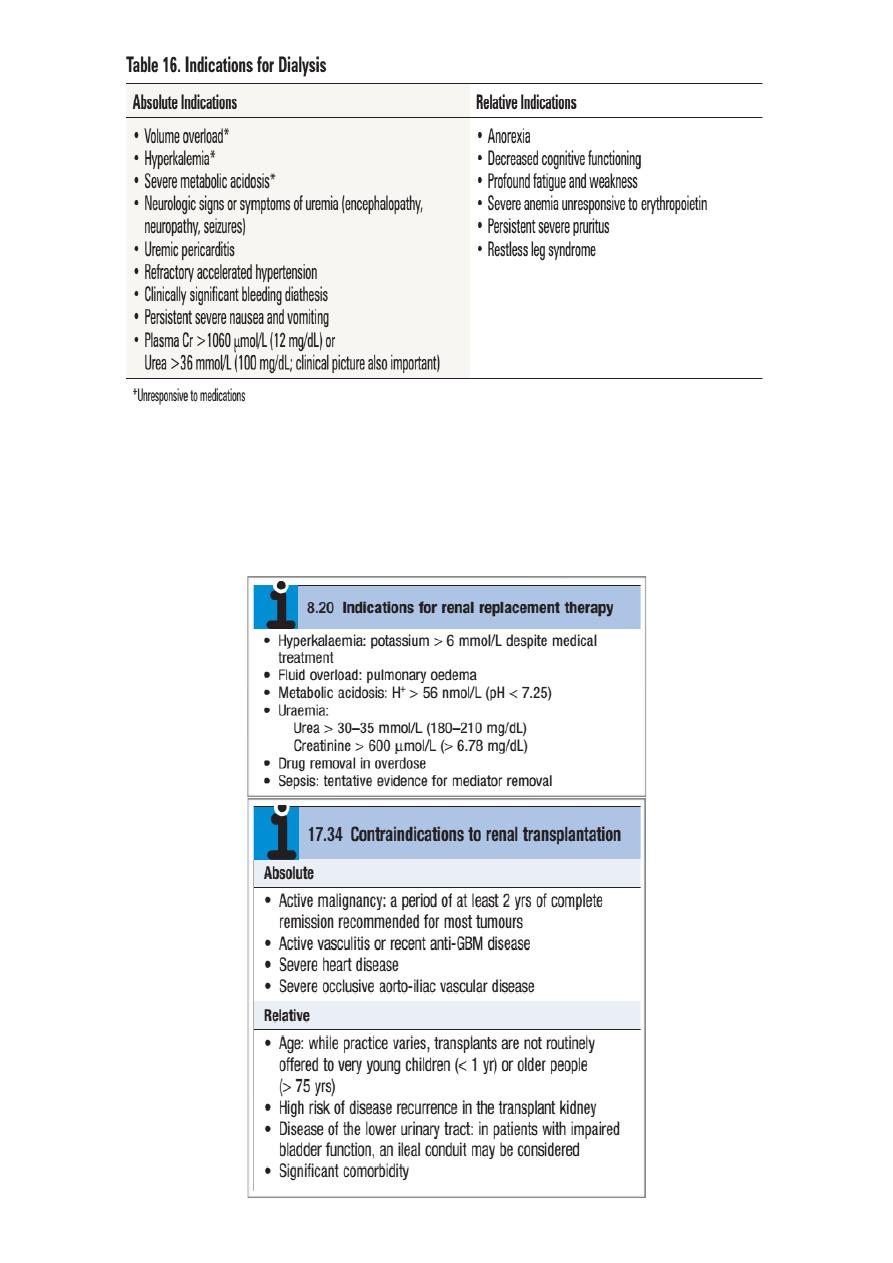

3. Renal replacement therapy (RRT)

((=

dialysis or kidney transplantation))

The aim of all renal replacement techniques is to mimic the excretory

functions of the normal kidney, including excretion of nitrogenous wastes,

maintenance of normal electrolyte concentrations, and maintenance of a normal

extracellular volume. At the present time, the average eGFR at the time of initiating

RRT in the UK is about 8 mL/min/1.73 m2 but there is wide variation. Since there is

no evidence that early initiation of RRT improves outcome, the overall aim is to

commence RRT by the time symptoms of CKD have started to appear but before

serious complications have occurred.

of

15

24

Renal transplantation offers the best chance of long term survival in ESRD,

and is the most cost effective treatment. Transplantation can restore normal kidney

function and correct all the metabolic abnormalities of CKD but requires long term

immunosuppression with its attendant risks. All patients with ESRD should be

considered for transplantation, unless there are contraindications.

of

16

24

Dialysis

Dr. ALI A. ALLAWI

Nephrologist and Transplant specialist

Internist

CABMS (NEPHROLOGY) , FICMS (NEPHROLOGY) FICMS (MEDICINE)

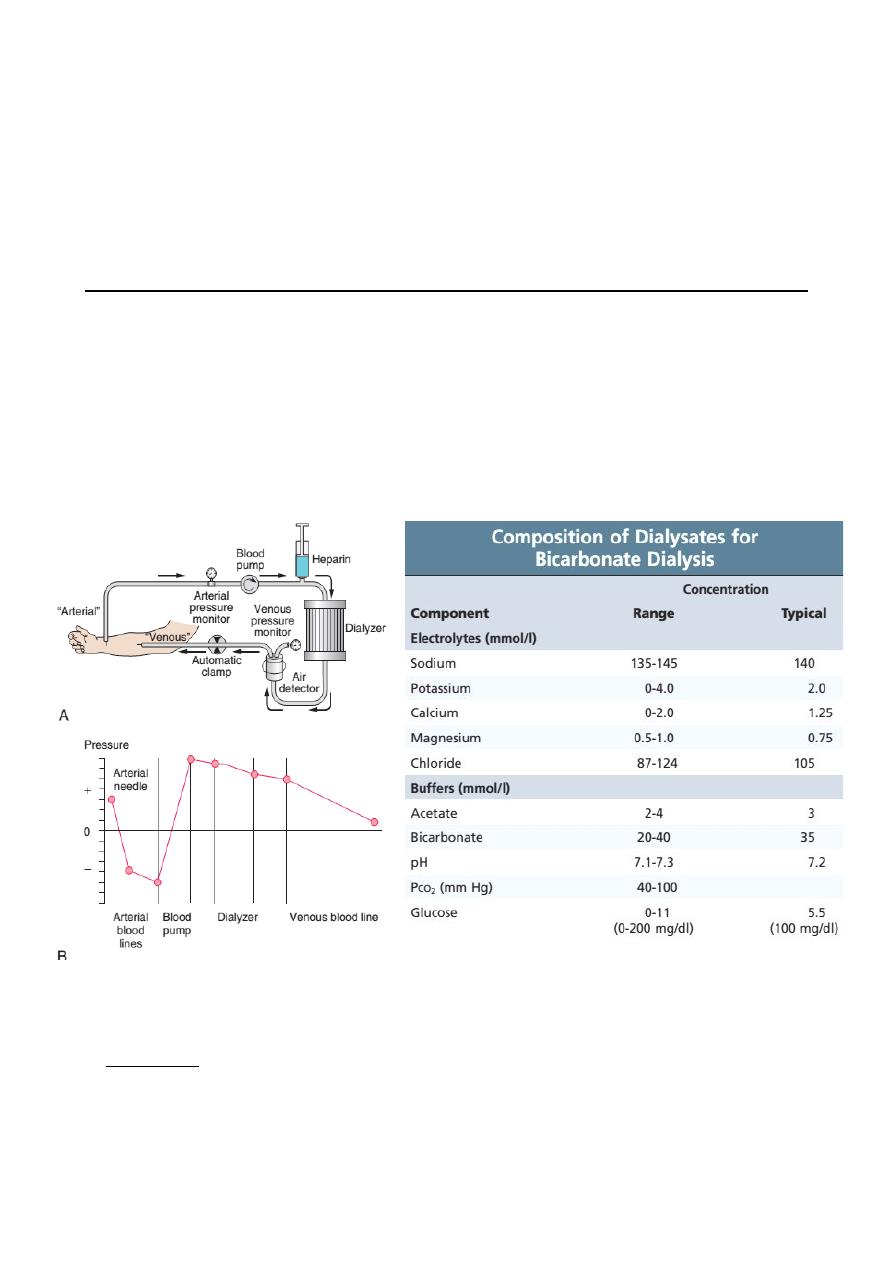

Haemodialysis

Basic principles

In haemodialysis, blood from the patient is pumped through an array of

semipermeable membranes (the dialyser, also called an hemofilter ), which bring

the blood into close contact with dialysate, flowing countercurrent to the blood.

The plasma biochemistry changes towards that of the dialysate owing to diffusion

of molecules down their concentration gradients.

Access for haemodialysis

Adequate dialysis requires a blood flow of at least 200 mL/min.

‣ AV Fistula : The most reliable long-term way of achieving this is surgical

construction of an arteriovenous fistula , using the radial or brachial artery and

the cephalic vein. This results in distension of the vein and thickening

(‘arterialization of veins’) of its wall, so that after 6–8 weeks large-bore needles

may be inserted to take blood to and from the dialysis machine.

of

17

24

‣ AV Graft: In patients with poor-quality veins or arterial disease (e.g. diabetes

mellitus), arteriovenous polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) grafts are used for access.

However, these grafts have a very high incidence of thrombosis and 2-year graft

patency is only 50–60%. Dipyridamole or fish oils improve graft patency but

warfarin, aspirin and clopidogrel do not and are associated with a high incidence

of complications.

‣ Double lumen catheter : If dialysis is needed immediately, a large-bore double

lumen catheter may be inserted into a central vein usually the jugular, femoral or

subclavian. The internal jugular vein route is preferred.

Haemodialysis in AKI

Haemodialysis offers the best rate of small solute clearance in AKI, as

compared with other techniques such as haemofiltration, but should be started

gradually because of the risk of confusion and convulsions due to cerebral oedema

(dialysis disequilibrium). Typically, 1–2 hours of dialysis is prescribed initially but,

subsequently, patients with AKI who are haemodynamically stable can be treated

by 4–5 hours of haemodialysis on alternate days, or 2–3 hours every day. During

dialysis, it is standard practice to anticoagulate patients with heparin but the dose

may be reduced if there is a bleeding risk. Epoprostenol can be used as an

alternative but carries a risk of hypotension.

of

18

24

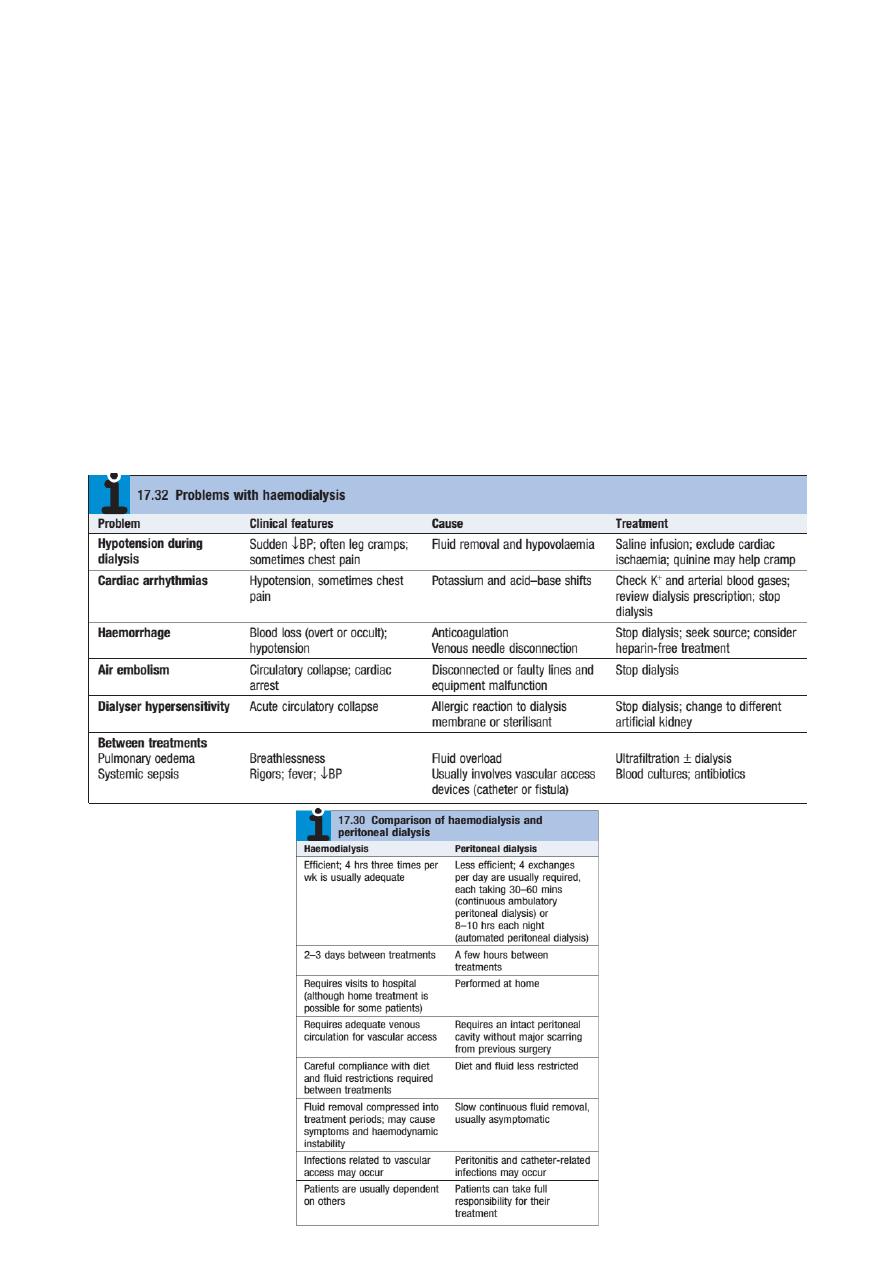

Haemodialysis in CKD

In CKD, vascular access for haemodialysis is gained by formation of an

arteriovenous fistula, usually in the forearm, up to a year before dialysis is

contemplated. After 4–6 weeks, increased pressure transmitted from the artery to

the vein leading from the fistula causes distension and thickening of the vessel wall

(arterialisation of vein). Largebore dual lumen catheter can then be inserted into the

vein to provide access for each haemodialysis treatment. Preservation of arm veins

is thus very important in patients with progressive renal disease who may require

haemodialysis in the future. Haemodialysis is usually carried out for 3–5 hours three

times weekly, in an outpatient dialysis unit. The intensity and frequency of dialysis

should be adjusted to achieve a reduction in urea during dialysis (urea reduction

ratio) of over 65%. Most patients notice an improvement in symptoms during the

first 6 weeks of treatment. Plasma urea and creatinine are lowered by each

treatment but do not return to normal.

of

19

24

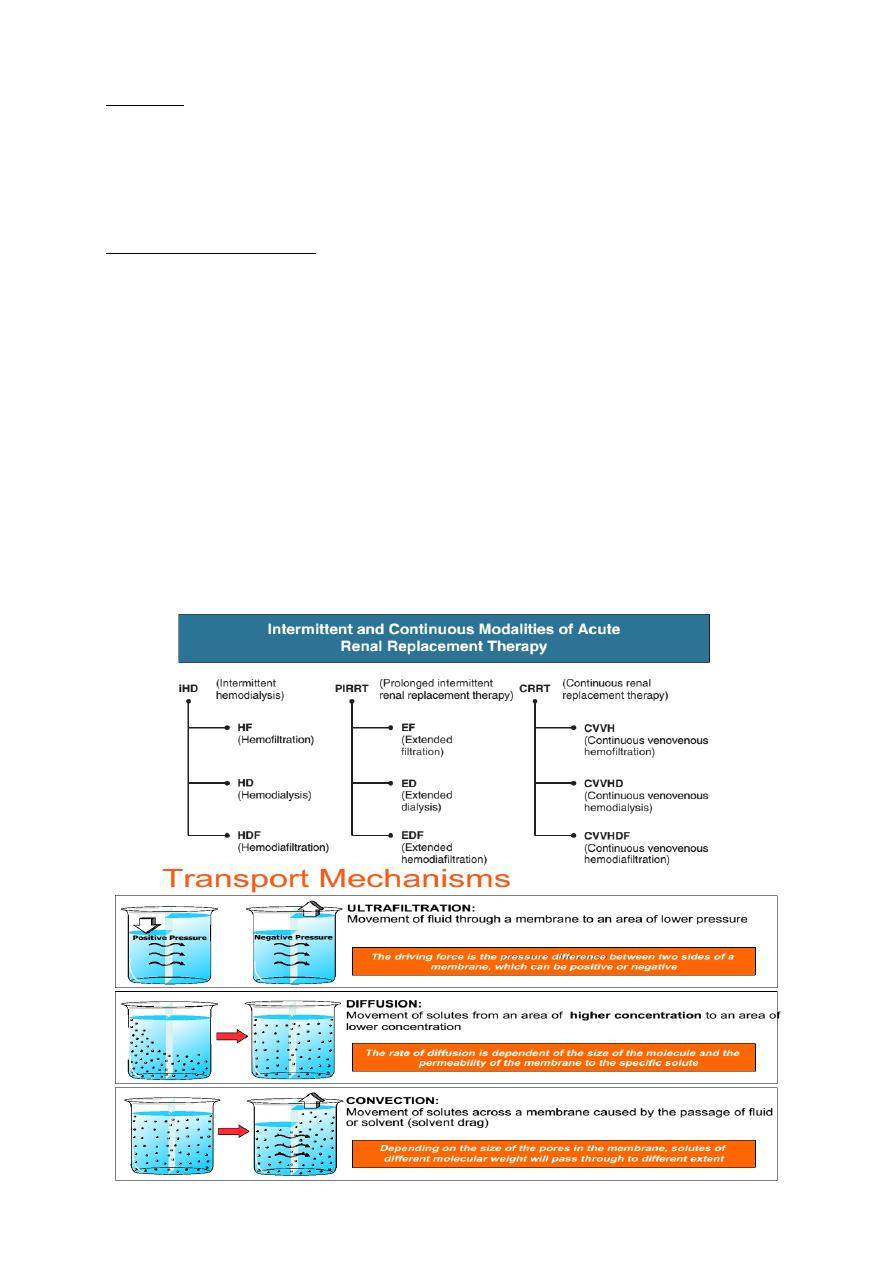

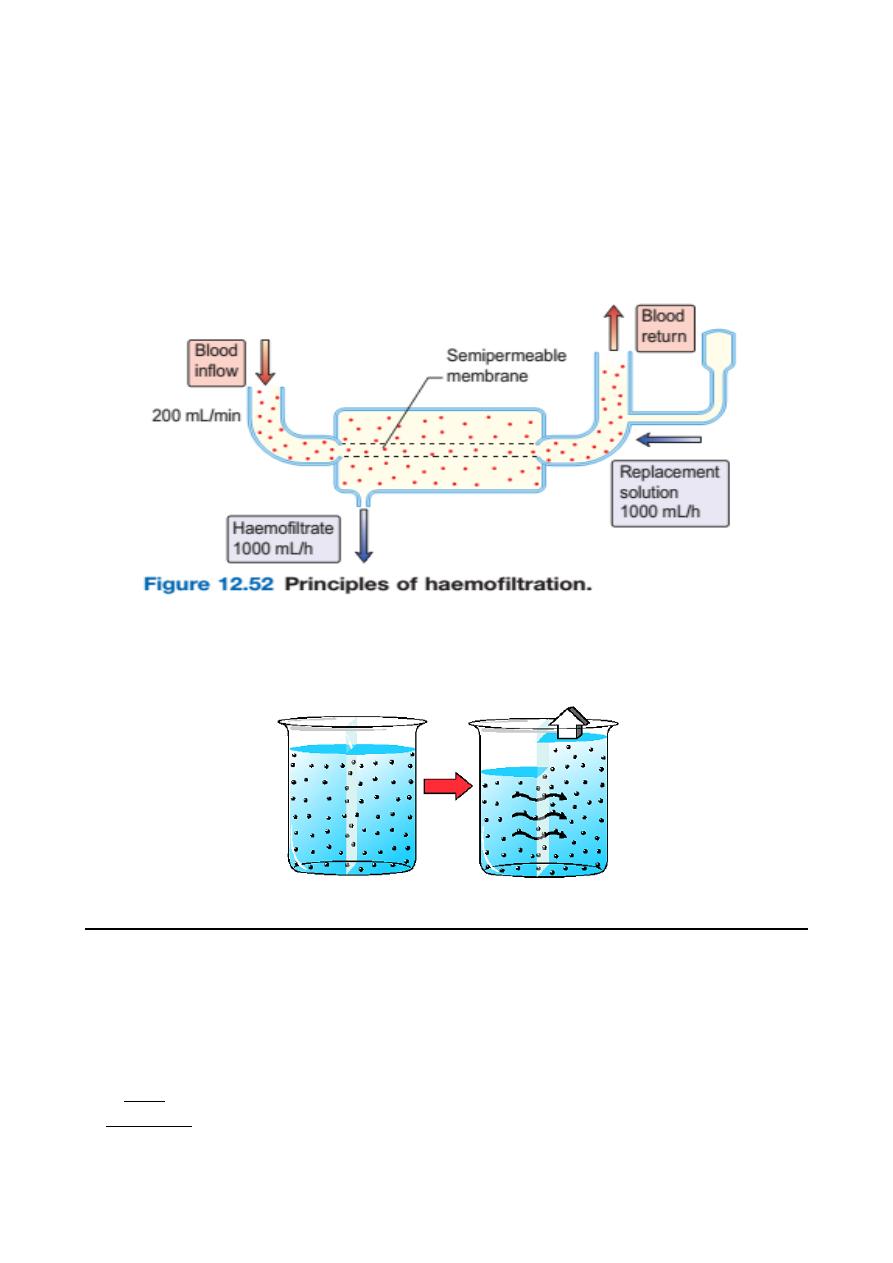

Haemofiltration

This involves removal of plasma water and its dissolved constituents (e.g. urea,

phosphate) by convective flow across a high-flux semipermeable membrane, and

replacing it with a solution of the desired biochemical composition.

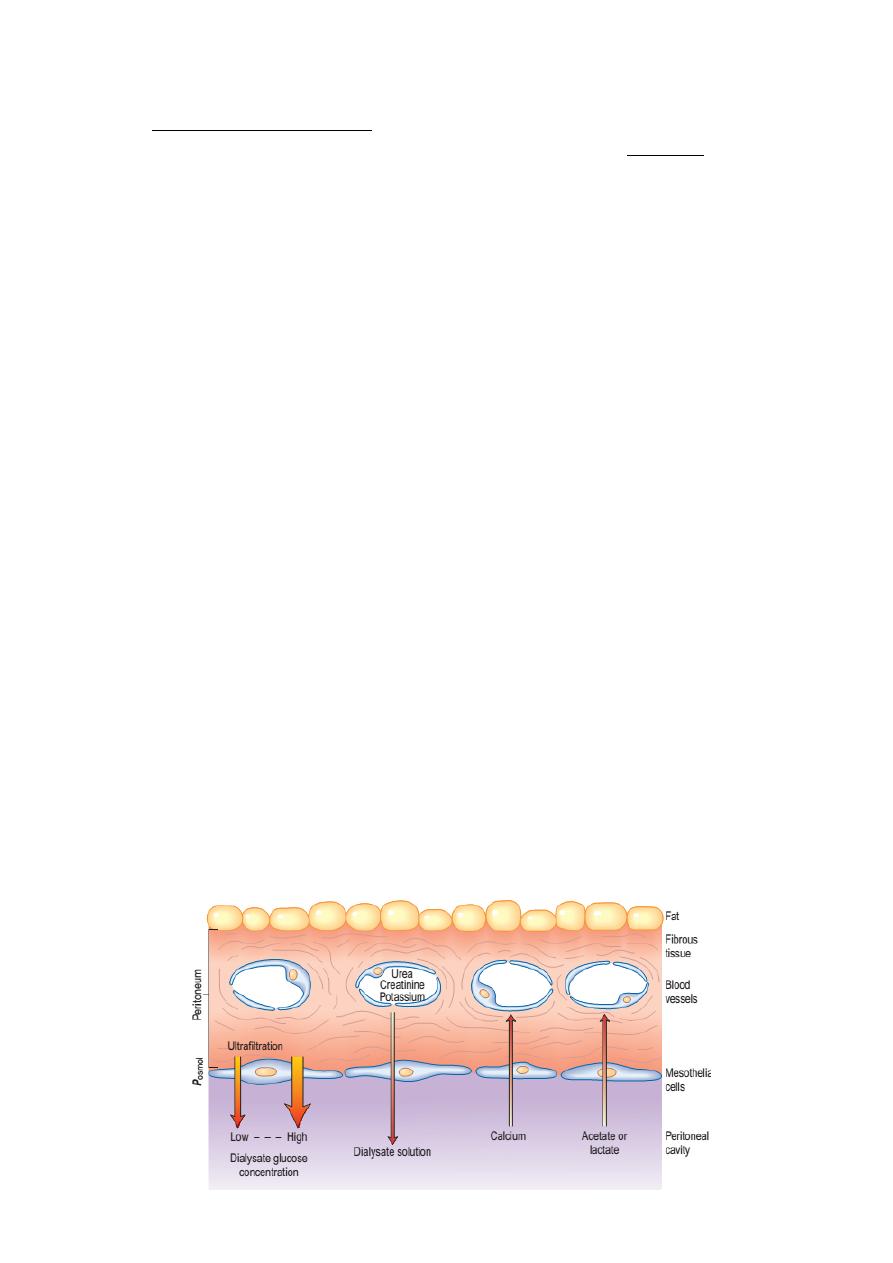

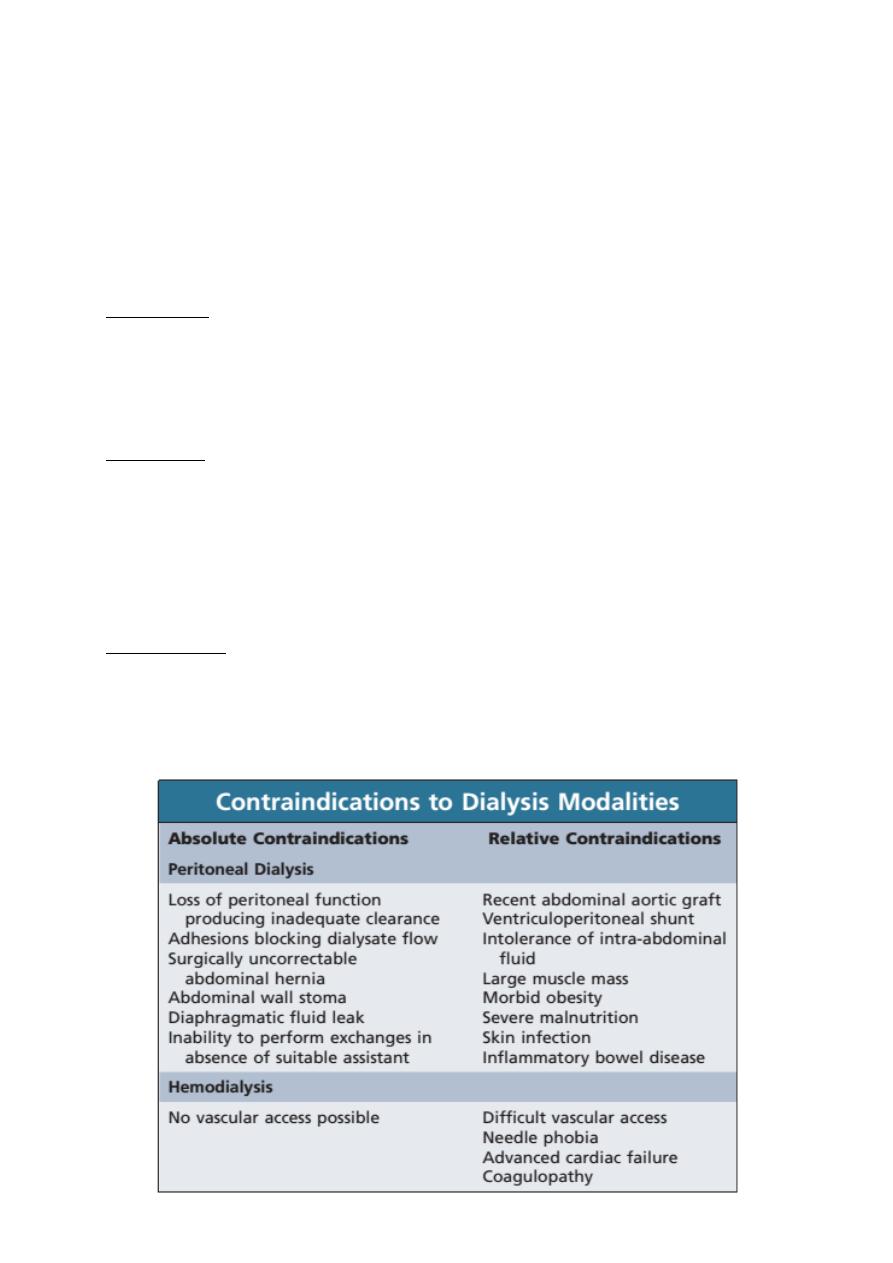

Peritoneal dialysis

Peritoneal dialysis utilizes the peritoneal membrane as a semipermeable

membrane, avoiding the need for extracorporeal circulation of blood. This is a very

simple technology treatment compared to haemodialysis. The principles are

simple:

‣ A tube is placed into the peritoneal cavity through the anterior abdominal wall.

‣ Dialysate is run into the peritoneal cavity, usually under gravity.

of

20

24

‣ Urea, creatinine, phosphate and other uraemic toxins pass into the dialyse down

their concentration gradients.

‣ Water (with solutes) is attracted into the peritoneal cavity by osmosis, depending

on the osmolarity of the dialysate. This is determined by the glucose or polymer

(icodextrin) content of the dialysate .

‣ The fluid is changed regularly to repeat the process.

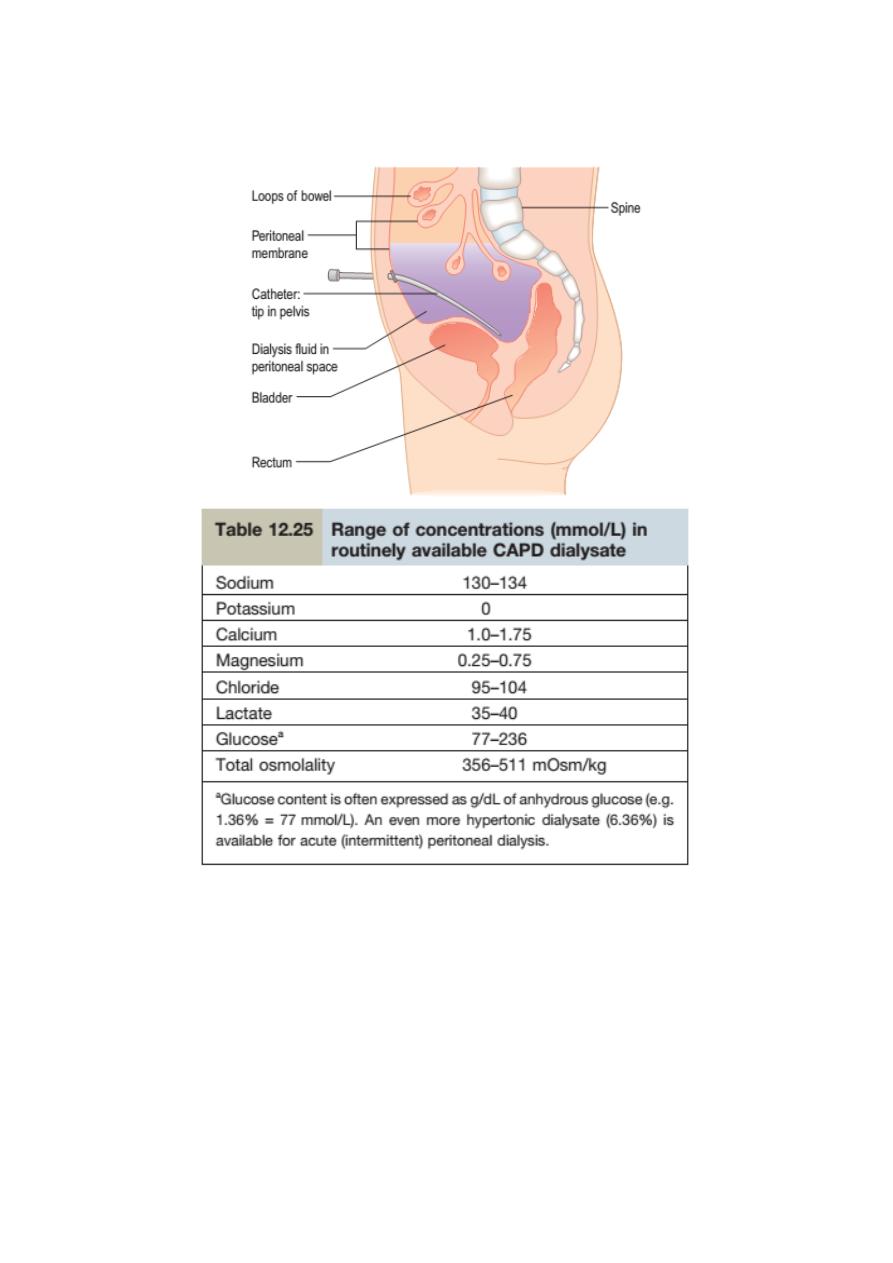

Chronic peritoneal dialysis

Requires insertion of a soft catheter, with its tip in the pelvis, exiting the

peritoneal cavity in the midline and lying in a skin tunnel with an exit site in the

lateral abdominal wall .This form of dialysis can be adapted in several ways.

Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD)

Dialysate is present within the peritoneal cavity continuously, except when

dialysate is being exchanged. Dialysate exchanges are performed three to five

times a day, using a sterile no-touch technique to connect 1.5–3 L bags of dialysate

to the peritoneal catheter; each exchange takes 20–40 min. This is the technique

most often used for maintenance peritoneal dialysis in

patients with ESKD.

Automated peritoneal dialysis (APD)

Also called Nightly intermittent peritoneal dialysis (NIPD). An automated

device (cycler) is used to perform exchanges each night while the patient is asleep.

Sometimes dialysate is left in the peritoneal cavity during the day in addition, to

increase the time during which biochemical exchange is occurring.

Few trials have demonstrated superiority of APD over CAPD with regard to

complications such as peritonitis, fluid status and in anuric patients.

Tidal dialysis: A residual volume is left within the peritoneal cavity with continuous

cycling of smaller volumes in and out.

of

21

24

Acute Peritoneal Dialysis Prescription

Acute peritoneal dialysis is usually performed manually but can be done with

the assistance of a cycler (automated machine) . It avoids the potential problems

related to vascular access (hemorrhage, air embolism, thrombosis, infection) and

does not require anticoagulation.

The gradual but continuous nature of the procedure results in effective

removal of fluid and solute with less hemodynamic instability.

Acute peritoneal dialysis is most often used in the setting of

‣ acute kidney injury(AKI ),

‣ it is also beneficial in the control of volume overload states in patients with

cardiovascular compromise, such as those with congestive heart failure, and

of

22

24

‣ in the treatment of hypothermia or

‣ hemorrhagic pancreatitis (where peritoneal lavage may be beneficial).

‣ It is most beneficial in the treatment of hemodynamically unstable patients or

patients in whom vascular access is problematic.

This is the combined time required for inflow, dwell, and drain. To maximize

dialysis efficiency in acute peritoneal dialysis, the exchange time most commonly

used is 1 hour

• Inflow time: Inflow is by gravity and usually requires about 10 minutes. It may be

prolonged due to kinking of the tubing or increased inflow resistance by intra-

abdominal tissues in close proximity to the catheter tip. Cold dialysate solution

also results in discomfort, and for this reason, the solution should be warmed to

37°C before infusion.

• Dwell time: The dwell period is the time during which the total exchange volume

is present in the peritoneal cavity (i.e., the time from the end of inflow to the

beginning of outflow).

Standard dwell period. When initiating peritoneal dialysis in acutely ill and

catabolic patients, the usual dwell time is 30 minutes to achieve an exchange time

of 60 minutes. With a 2-L exchange volume, 48 L of fluid will thus be exchanged

daily.

• Outflow time: Outflow of spent dialysate is by gravity and usually requires 20-30

minutes. If outflow continues to be poor, then outflow obstruction should be

managed . Pain during outflow is unusual, but localized pain may occasionally be

noted at the end of a drain due to a siphoning effect of the catheter on the

peritoneum.

of

23

24

of

24

24