1

Histology

Prof. Dr. Faraid

Lec.5

LIVER

The liver is located in the peritoneal cavity below the diaphragm.

The liver is the largest gland in the body and is the second largest organ

(the largest is the skin), weighing about 1.5 Kg in the adult. The liver

produces bile and plays a major role in lipid, carbohydrate, and protein

metabolism. The liver inactivates and metabolizes many toxic

substances and drugs. It also participates in iron metabolism and the

synthesis of blood proteins and the factors necessary for blood

coagulation. Elimination of toxic substances occurs in the bile, an

exocrine secretion of the liver that is important for lipid digestion.

The liver is covered by a thin connective tissue capsule (Glisson's

capsule) that becomes thicker at the hilum (porta hepatis) where the

portal vein and the hepatic artery enter the organ and where the right

and the left hepatic ducts and lymphatics exit. Trabeculae arise from the

capsule subdivide the liver into lobes and lobules. In man the trabeculae

are very incomplete.

The structural units of the liver are called liver lobules. In certain

animals (eg. pigs) these lobules are separated from each other and

sharply delimited by a layer of connective tissue. This is not the case in

humans, making it difficult to establish the exact limits between

different lobules.

Liver Lobules

:

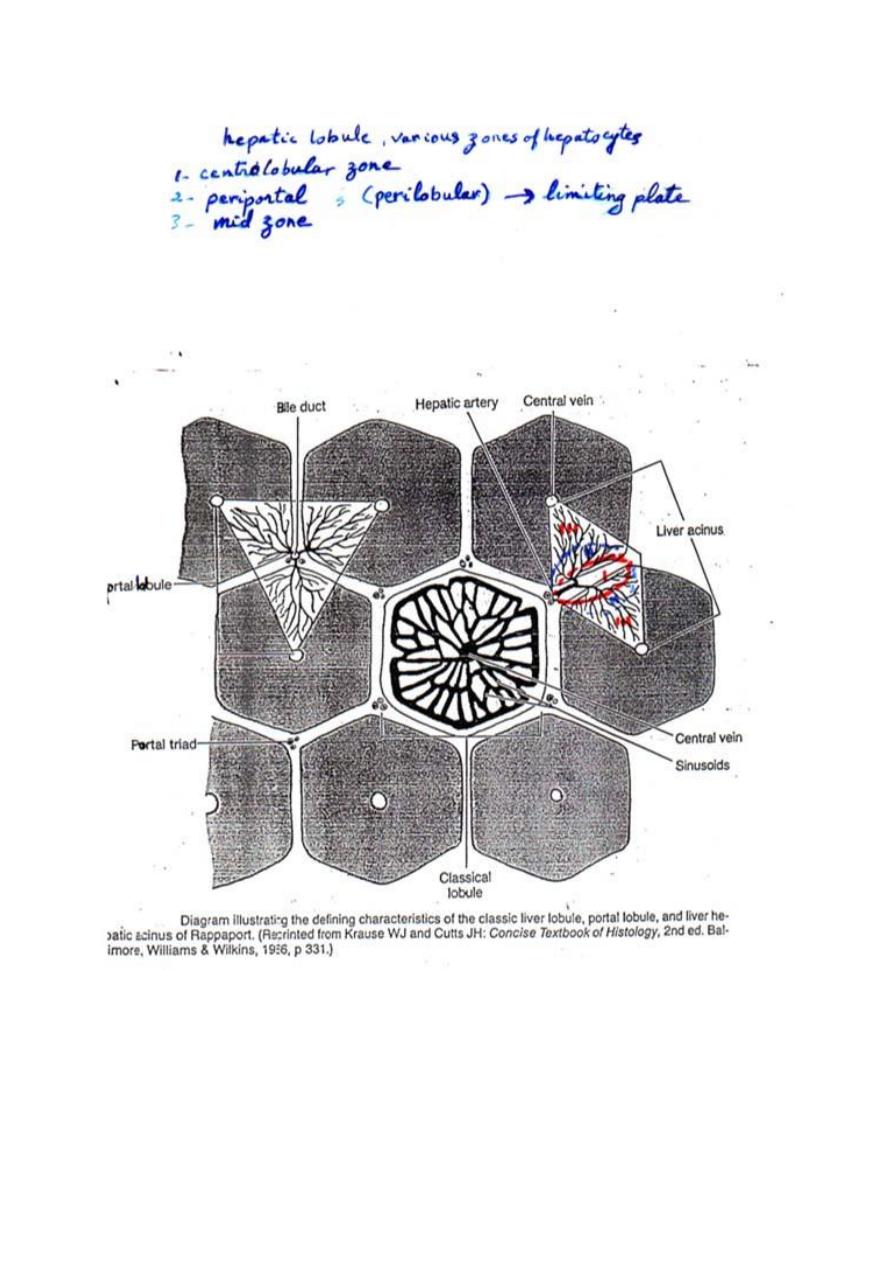

1. Classic Liver Lobule: (this is based on the direction of the blood

flow)

It is a hexagonal mass of tissue primarily composed of plates of

hepatocytes which radiate from the region of the central vein (present in

2

the center) toward the periphery. The plates are separated by hepatic

sinusoids. At the corners of the lobule, there is the portal canals [portal

areas, portal tracts, portal spaces or portal triad].Each portal canal

contains: a portal venule (a branch of portal vein), a hepatic arteriole (a

branch of hepatic artery), bile duct and lymphatic vessels. These

structures are surrounded by loose connective tissue.

The arterial and venous blood flows centripetally in each lobule (from

the portal areas to drain in the central vein), whereas the bile flows

centrifugally towards the portal areas.

In the lobule, various zones of hepatocytes can be identified. These are

the centrolobular, periportal, and mid zones.

1. The centrolobular zone: is composed of hepatocytes surrounding

the central vein, and is the zone most distant from the oxygenated

arterial blood supply.

2. The periportal (perilobular zone): at the periphery of the lobule, is

closely related to the portal tracts. The outermost layer of

periportal hepatocytes immediately adjacent to the portal tract is

called the limiting plate; it is the first group of hepatocytes to be

damaged in liver disorders that primarily involve the portal tracts.

3. The mid zone: is the zone of hepatocytes between the

centrolobular and periportal zones.

2. Portal Lobule: (this is based mainly on the direction of bile flow)

It is a triangular region with a portal triad at its center and a central vein

at each of its three corners. It contains portions of three adjacent classic

liver lobules all of which drain bile into one portal canal.

3. Hepatic Acinus (of Rappaport): (it is based on changes in oxygen,

nutrient, and toxin content as blood flowing through the sinusoids is

acted on by hepatocytes)

It is that region which is supplied by a terminal branch of the portal vein

and hepatic artery and drained by a terminal branch of the bile duct. It is

3

a diamond-shaped region, contains portions (triangular sections) of two

adjacent classic liver lobules (whose apices are the central veins).

In relation to their proximity to the distributing vessels, cells in the

hepatic acinus can be subdivided into three zones. Cells in zone I would

be those closest to the distributing vessels, whereas zone III is closer to

the central vein. Zone II is intermediate between zone I and III. Blood in

zone I sinusoids has higher oxygen, nutrient, and toxin concentrations

than in the other zones. As the blood flows toward the central vein,

these substances are gradually removed by hepatocytes. Zone I

hepatocytes thus have a higher metabolic rate and larger glycogen and

lipid stores. They are also more susceptible to damage by blood-borne

toxins, and their energy stores are the first to be depleted during fasting.

This explains regional histopathologic differences in patients with liver

damage.

Hepatocytes:

They are the main cells of the lobules. They are epithelial cells (derived

from embryonic endoderm).

They are arranged in plates that anastomose freely and separated from

each other by spaces filled by hepatic sinusoids and are disposed

radially around the central vein. Hepatocytes are large polyherdral cells

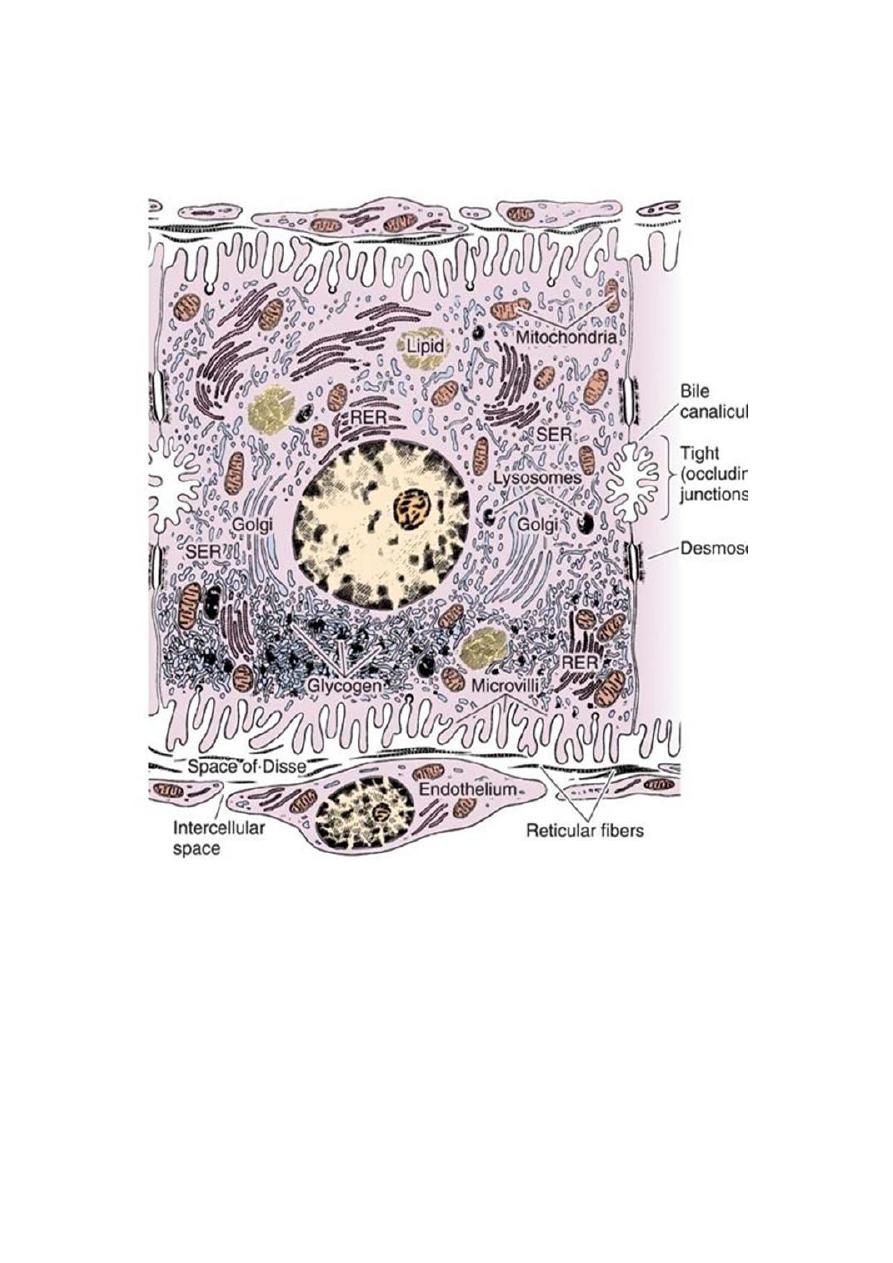

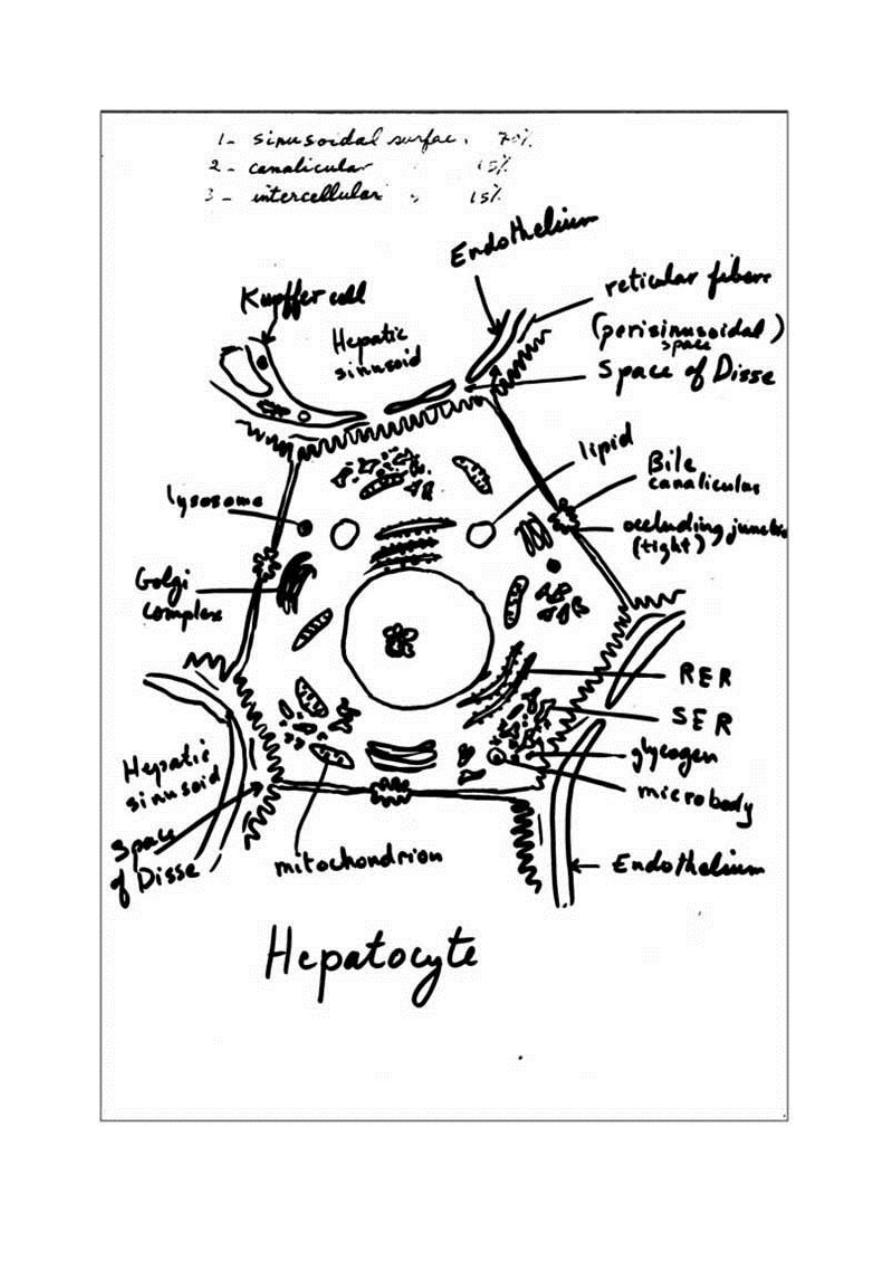

(20-30 µm in diameter). Hepatocytes have three important surfaces:

1- Sinusoidal surfaces: are separated from the sinusoidal vessel by

the space of Disse. They account for approximately 70% of the

total hepatocyte surface. They are covered by short microvilli,

which protrude into the space of Disse. The sinusoidal surface is

the site where material is transferred between the sinusoids and the

hepatocyte.

2- Canalicular surfaces: are the surfaces across which bile drains

from the hepatocytes into the canaliculi. They account for

approximately 15% of the hepatocyte surface.

4

3- The intercellular surfaces: are the surfaces between adjacent

hepatocytes that are not in contact with sinusoids or canaliculi.

They account for about 15% of the hepatocyte surface.

Hepatocytes usually contain one round, central nucleus; some are

binucleated (25%). Occasionally nuclei are polyploid (more than one set

of chromosomes). The cytoplasm of the hepatocytes is typically fairly

acidophilic (many mitochondria and some SER), with areas of

basophilia (rough endoplasmic reticulum). The hepatocytes are unusual

in that they possess abundant RER and SER in the same cells. The RER

is associated with protein synthesis such as: albumin, fibrinogen,

globulin, prothrombin. The SER is associated with steroid metabolism

and also is responsible for the processes of oxidation, methylation, and

conjugation required for inactivation or detoxification of various

substances before their excretion from the body.

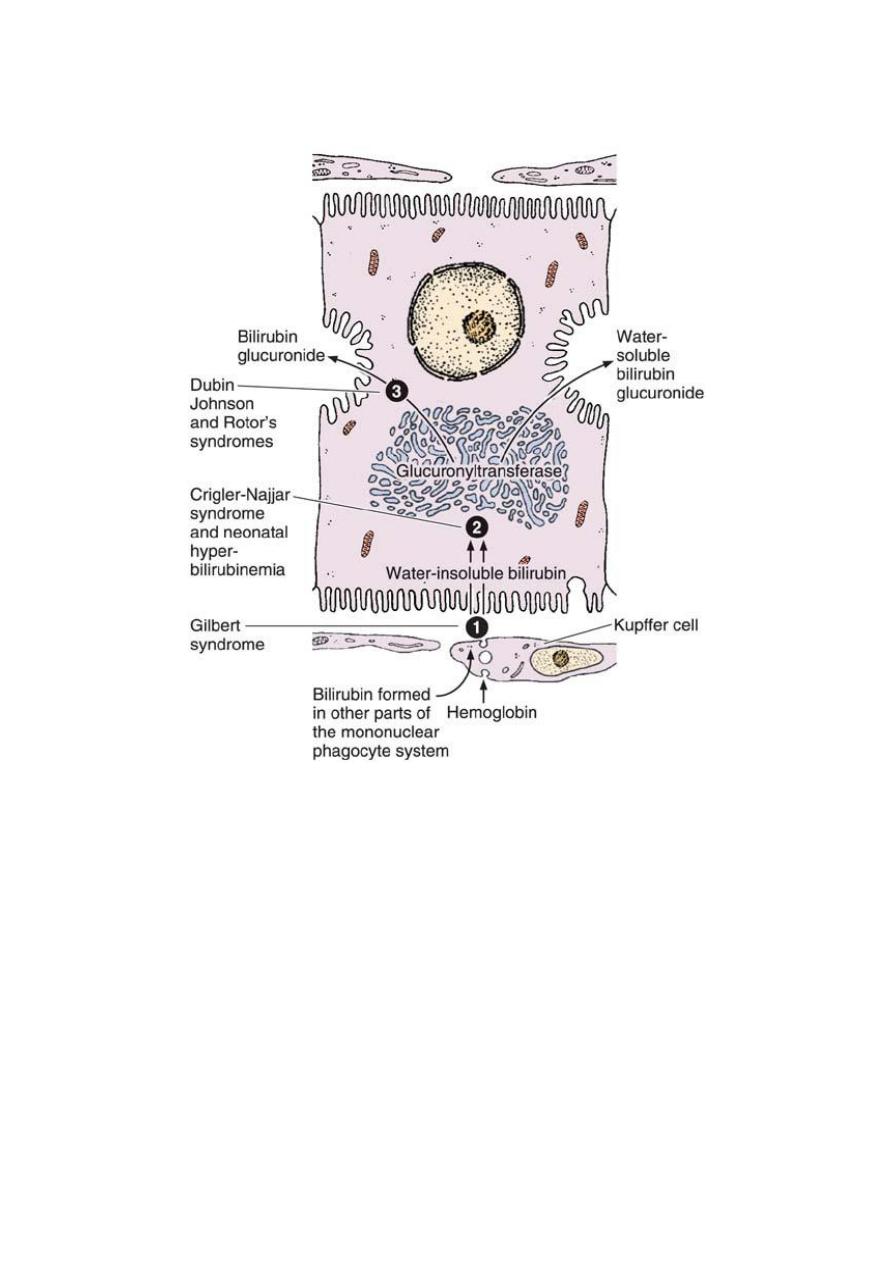

One of the main processes occurring in the SER is the conjugation of

water-insoluble toxic bilirubin with glucuronide by glucuronyl-

transferase activity to form a water-soluble nontoxic bilirubin

glucuronide. This conjugate is excreted by hepatocytes into the bile.

When bilirubin or bilirubin glucuronide is not excreted, various diseases

characterized by jaundice can result.

Each hepatocyte has approximately 2000 mitochondria. Golgi

complexes are also numerous up to 50 per cell. The functions of this

organelle include the formation of lysosomes and the secretion of

plasma proteins (eg. albumin, proteins of the complement system),

glycoproteins (eg. transferrin), and lipoproteins (eg. very low-density

lipoproteins). Hepatocytes possess lysosomes which are important in the

turnover and degradation of interacellular organelles. Peroxisomes are

abundant. Lipid droplet and glycogen are found in varying amounts

depending upon the functional state of the cells. The glycogen appears

in the electron microscope as coarse, electron dense granules that

frequently collect close to the SER.

5

The hepatocyte is probably the most versatile cell in the body. It is a

cell with both endocrine and exocrine functions. Endocrine secretion

involves the production and release of several plasma proteins. Unlike

other protein synthesizing and secreting cells of the body, the

hepatocytes are unusual in that they lack protein storage granules.

Exocrine secretion involves the production and release of bile.

Hepatocytes located at different distances from the portal triads show

differences in structural, histochemical, and biochemical characteristics.

Bile canaliculi: are the first portions of the bile duct system. They are

tubular spaces 1-2 µm in diameter, limited only by the plasma

membranes of 2 adjacent hepatocytes and have a small number of

microvilli in their interiors. The cell membranes near these canaliculi

are sealed together by tight junctions. The canaliculi drain outwards in

the direction of the portal canal. The bile flow therefore progresses in a

direction opposite to that of the blood, i.e., from the center of the lobule

to its periphery. At the periphery, bile enters the bile ductules (or

Hering's canals), lined with simple cuboidal epithelium. After a short

distance, the ductules cross the limiting hepatocytes of the lobule and

end in the bile ducts in the portal spaces. Bile ducts are lined by simple

cuboidal or columnar epithelium and have a distinct connective tissue

sheath. They gradually enlarge and fuse, forming right and left hepatic

ducts, which leave the liver, unite to form a common hepatic duct. The

hepatic duct after receiving the cystic duct from the gallbladder

continues to the duodenum as the common bile duct. The hepatic, cystic,

and common bile ducts are lined with simple columnar epithelium.

Hepatic sinusoids: are vessels that arise at the periphery of a lobule and

run between adjacent plates of hepatocytes. They receive blood from the

vessels in the portal areas and deliver it to the central vein. Sinusoids are

larger than capillaries, more irregular in shape and their lining cells are

directly related to the epithelial cells with no intervening connective

tissue.The lining of the sinusoids consists of a discontinuous layer of

fenestrated endothelium also contain Kupffer cells in their endothelial

lining. They lack basal lamina.

6

Kupffer cells: are mononuclear phagocytic cells (fixed macrophages)

derived from blood monocytes and located in the lining of hepatic

sinusoids. They are large cells with several processes, and exhibit an

irregular or stellate outline. Their main functions are to metabolize aged

erythrocytes,

digest

hemoglobin,

secrete

proteins

related

to

immunologic processes, and destroy bacteria that enter the portal blood

through the large intestine.

Space of Disse: is the perisinusoidal space located between hepatocytes

and the endothelium of hepatic sinusoids. It contains microvilli of the

hepatocytes, plasma, reticular fibers, and fat-storing cells (Ito cells).

Blood plasma enters this space through openings between the

endothelial cells that are too small for blood cells to pass. Blood-borne

substances thus directly contact the microvilli of hepatocytes. These

cells absorb nutrients, oxygen, and toxins from, and release endocrine

secretions into, these spaces.

It functions in the exchange of material between the bloodstream and

hepatocytes, which do not directly contact the blood stream.

Fat-storing (Ito) cells: are stellate cells lie in the space of Disse and

have the ability to accumulate lipid droplets. They are the main source

of vitamin A storage in the body and also play a role in wound healing

(hepatic fibrogenesis).

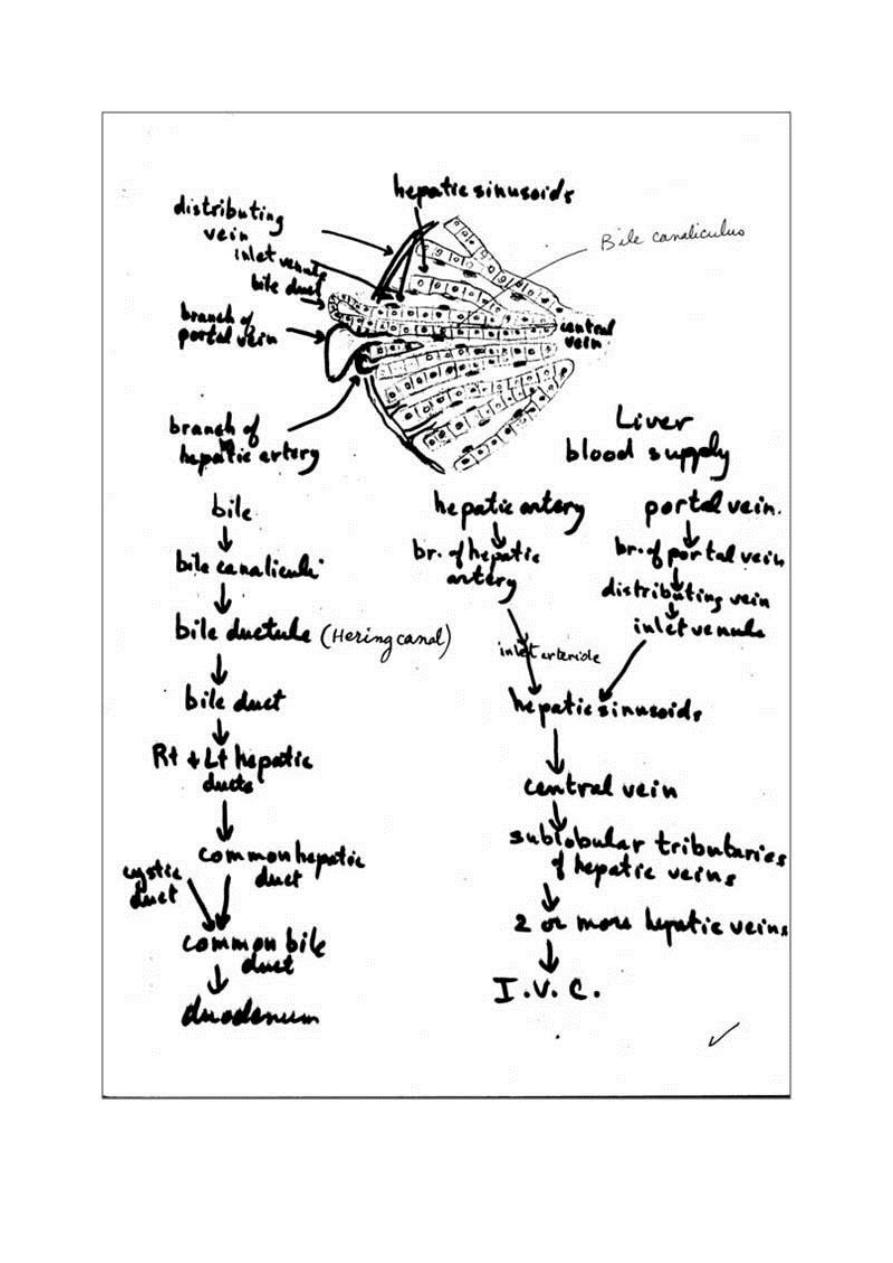

Blood supply of the liver:

The liver is unusual in that it receives blood from two sources:70- 80%

of the blood derives from the portal vein, which carries oxygen-poor,

nutrient-rich blood from the abdominal viscera, and 20-30% derives

from the hepatic artery, which supplies oxygen-rich blood.

7

Portal vein system:

The portal vein branches repeatedly and sends small portal venules to

the portal spaces. The portal venules branch into the distributing veins

that run around the periphery of the lobule. From the distributing veins,

small inlet venules empty into the sinusoids. The sinusoids run radially,

converging in the center of the lobule to form the central, or

centrolobular, vein. The central vein has thin walls consisting only of

endothelial cells supported by a sparse population of collagen fibers. As

the central vein progresses along the lobule, it receives more and more

sinusoids and gradually increases in diameter. At its end, it leaves the

lobule at its base by merging with the larger sublobular vein. The

sublobular veins gradually converge and fuse, forming the two or more

large hepatic veins that empty into the inferior vena cava.

The portal system conveys blood from the pancreas and spleen and

blood containing nutrients absorbed in the intestines. The portal vein is

formed by the junction of mesenteric and splenic veins.

Arterial system:

The hepatic artery branches repeatedly and forms the interlobular

arteries (hepatic arterioles). Some of these arteries irrigate the structures

of the portal canal, and others form arterioles (inlet arterioles) that end

directly in the sinusoids, thus providing a mixture of arterial and portal

venous blood in the sinusoids. The hepatic artery is a branch of the

celiac artery of the abdominal aorta.

Blood flows from the periphery to the center of the liver lobule.

Consequently, oxygen and metabolites, as well as all other toxic or

nontoxic substances absorbed in the intestines, reach the peripheral cells

first and then reach the central cells of the lobule. This direction of

blood flow explains why the behavior of perilobular cells differs from

that of the centrolobular cells. This is particularly evident in pathologic

8

specimens, where changes are seen in either the central cells or the

peripheral cells of the lobule.

Liver Regeneration:

Despite its low rate of cell renewal, the liver has an extraordinary

capacity for regeneration. The process of regeneration is probably

controlled by circulating substances called chalones, which inhibit the

mitotic division of certain cell types. When a tissue is injured or

partially removed, the number of chalones it produces decreases;

consequently, a burst of mitotic activity occurs in this tissue. As

regeneration proceeds, the quantity of chalones produced increases and

mitotic activity decreases. This process is self-regulating. The

regenerated liver tissue is usually similar to the removed tissue. If there

is continuous or repeated damage to hepatocytes over a long period, the

multiplication of liver cells is followed by a pronounced increase in the

amount of connective tissue. The excess of connective tissue results in

disorganization of the liver structure, a condition known as cirrhosis, is

a progressive and irreversible process, causes liver failure, and is usually

fatal.

Cirrhosis is a consequence of any sustained progressive injury to

hepatocytes produced by several agents, such as ethanol, drugs or other

chemicals, hepatitis virus, and autoimmune liver disease.

9

11

Ultrastructure of a hepatocyte. RER, rough endoplasmic reticulum;

SER, smooth endoplasmic reticulum. x10,000

11

12

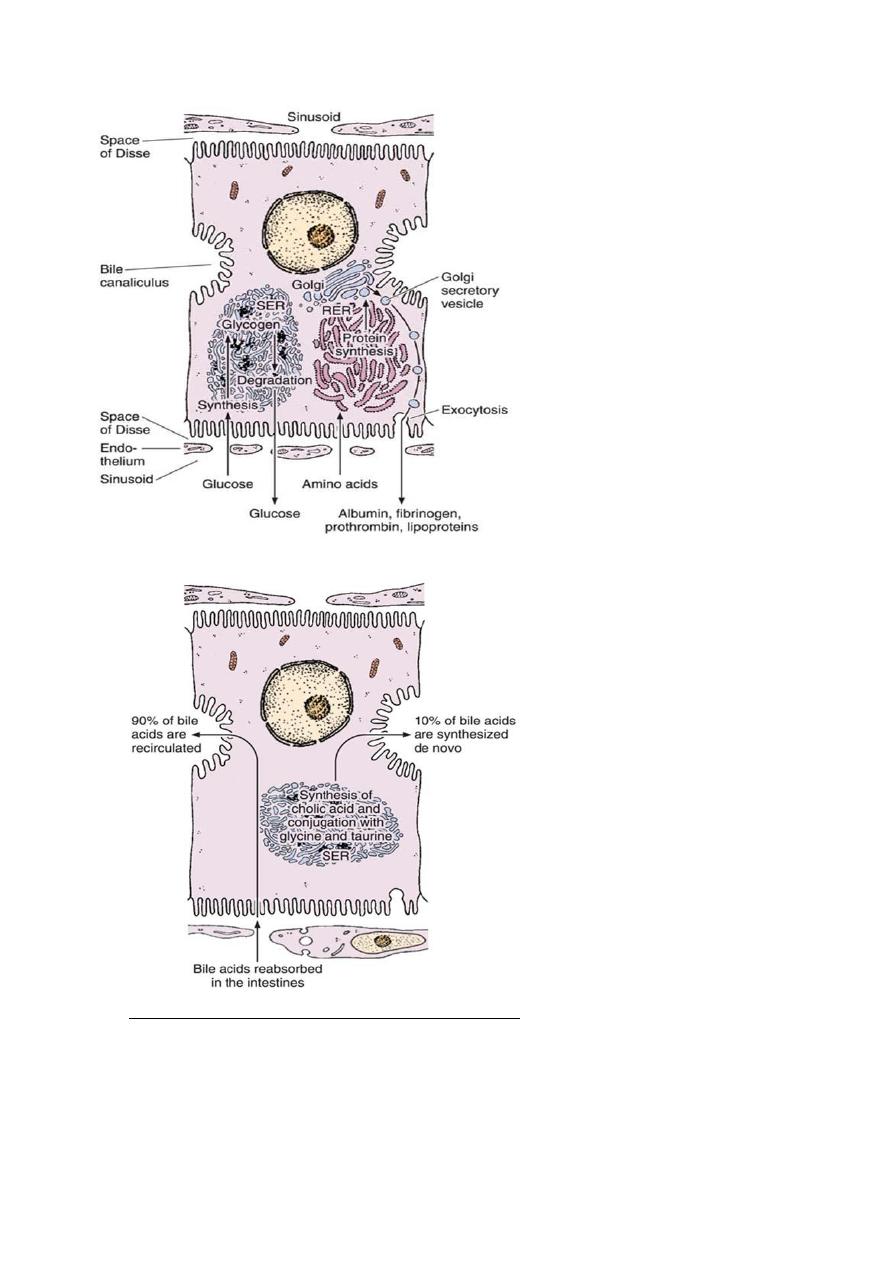

Protein synthesis and carbohydrate

storage in the liver. Carbohydrate is

stored as glycogen, usually associated

with the smooth endoplasmic reticulum

(SER). When glucose is needed, glycogen

is degraded. In several diseases, glycogen

degradation is depressed, resulting in

abnormal intracellular accumulations of

glycogen. Proteins produced by

hepatocytes are synthesized in the rough

endoplasmic reticulum (RER), which

explains why hepatocyte lesions or

starvation lead to a decrease in the

amounts of albumin, fibrinogen, and

prothrombin in a patient’s blood. The

impairment of protein synthesis leads to

several complications, since most of these

proteins are carriers, important for the

blood’s osmotic pressure and for

coagulation.

Mechanism of secretion of bile acids. About 90% of bile acids are derived from the

intestinal epithelium and transported to the liver. The remaining 10% are synthesized in

the liver by the conjugation of cholic acid with the amino acids glycine and taurine. This

process occurs in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER).

13

The secretion of bilirubin. The water-insoluble form of bilirubin is derived from the

metabolism of hemoglobin in macrophages. Glucuronyltransferase activity in the

hepatocytes causes bilirubin to be conjugated with glucuronide in the smooth endoplasmic

reticulum, forming a water-soluble compound. When bile secretion is blocked, the yellow

bilirubin or bilirubin glucuronide is not excreted; it accumulates in the blood, and

jaundice results. Several defective processes in the hepatocytes can cause diseases that

produce jaundice: a defect in the capacity of the cell to trap and absorb bilirubin (1), the

inability of the cell to conjugate bilirubin because of a deficiency in glucuronyltransferase

(2), or problems in the transfer and excretion of bilirubin glucuronide into the bile

canaliculi (3). One of the most frequent causes of jaundice, however–unrelated to

hepatocyte activity–is the obstruction of bile flow as a result of gallstones or tumors of the

pancreas.

14

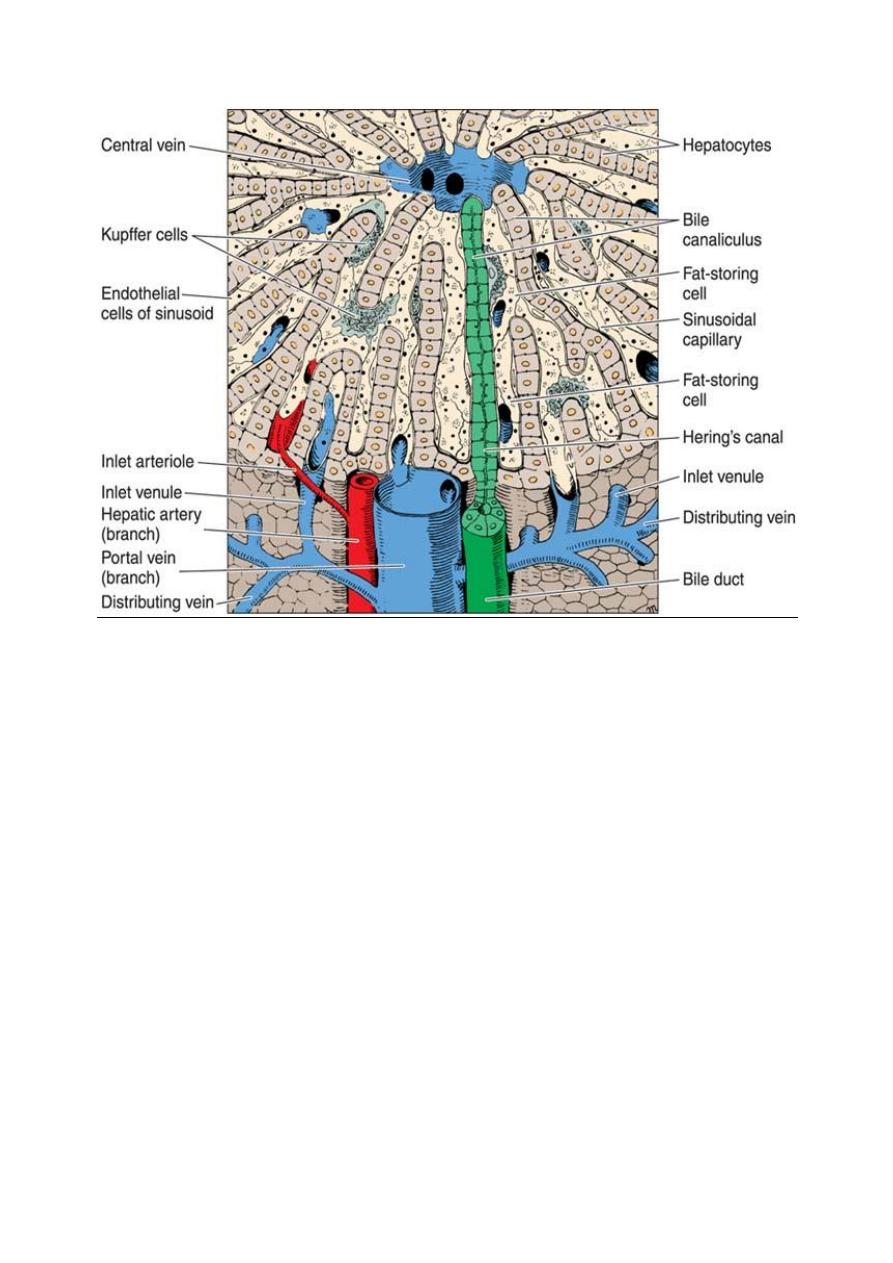

Three-dimensional aspect of the normal liver. In the upper center is the

central vein; in the lower center is the portal vein. Note the bile canaliculus,

liver plates, Hering’s canal, Kupffer cells, sinusoid, fat-storing cell, and

sinusoid endothelial cells. (Courtesy of M Muto.)

15

16

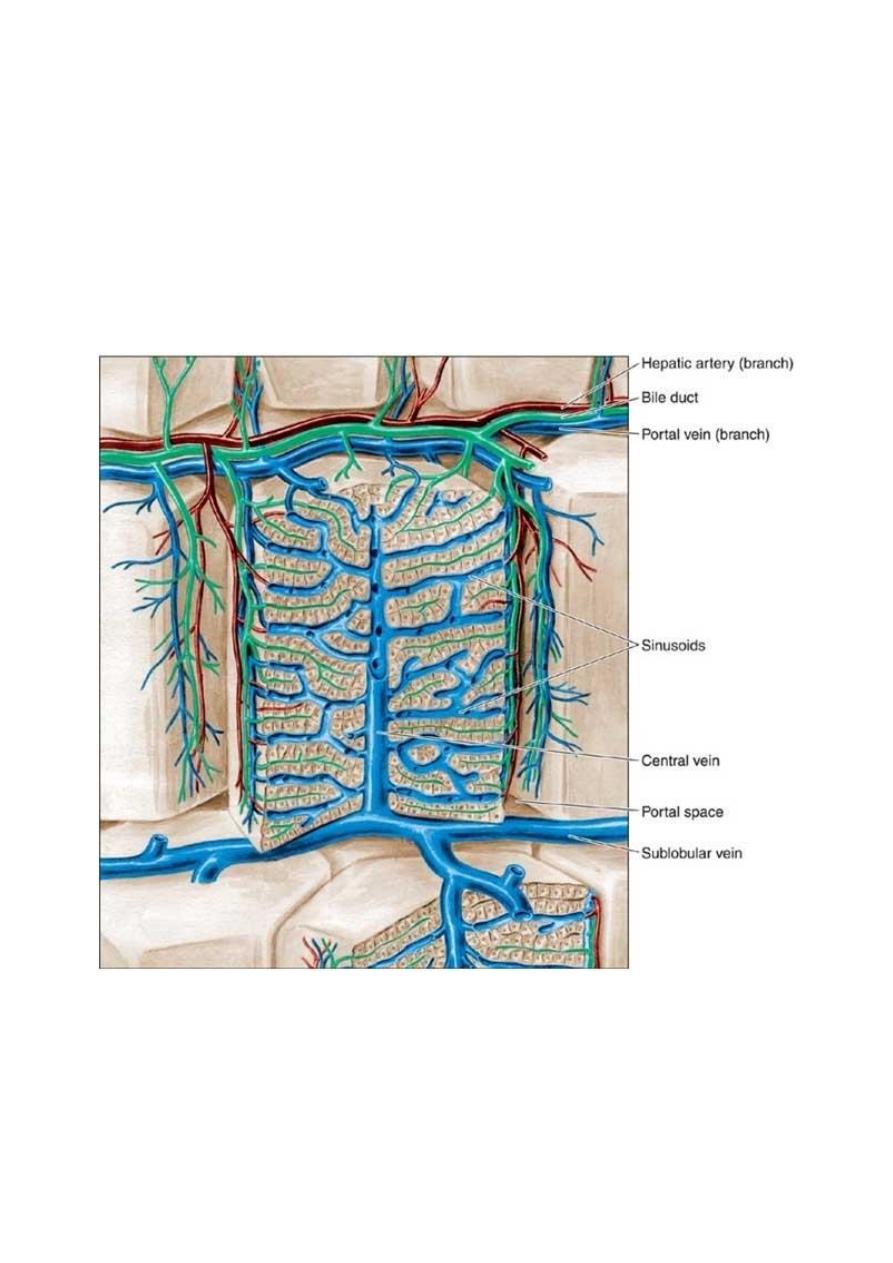

Schematic drawing of the structure of the liver. The liver lobule in the center is

surrounded by the portal space (dilated here for clarity). Arteries, veins, and bile ducts

occupy the portal spaces. Nerves, connective tissue, and lymphatic vessels are also present

but are (again, for clarity) not shown in this illustration. In the lobule, note the radial

disposition of the plates formed by hepatocytes; the sinusoidal capillaries separate the

plates. The bile canaliculi can be seen between the hepatocytes. The sublobular

(intercalated) veins drain blood from the lobules. (Redrawn and reproduced, with

permission, from Bourne G: An Introduction to Functional Histology. Churchill, 1953.