Lecture 3

Physiology

Dr. Affan Ezzat

1

Physiology of the body fluids

Objectives: By the end of these two lectures, you will be able to:

- Describe the daily water intake and loss by the human body.

- Define body fluid compartments.

- List the important constituents of extracellular and intracellular compartments.

- Outline the regulation of fluid exchange and osmotic equilibrium between

extracellular and intracellular fluid.

- Describe the volume and osmolality of Extracellular and Intracellular Fluids in

abnormal States.

- State the filtration across capillaries.

- Define edema.

Daily Intake of Water

Water is added to the body by two major sources: (1) it is ingested in the form of liquids or water

in the food, which together normally add about 2100 ml/day to the body fluids, and (2) it is

synthesized in the body as a result of oxidation of carbohydrates, adding about 200 ml/day. This

provides a total water intake of about 2300 ml/day. Intake of water, however, is highly variable

among different people and even within the same person on different days, depending on

climate, habits, and level of physical activity.

Daily Loss of Body Water

(1)Insensible Water Loss.

Some of the water losses cannot be precisely regulated. For example,

there is a continuous loss of water by evaporation from the respiratory tract and diffusion

through the skin, which together account for about 700 ml/day of water loss under normal

conditions. This is termed insensible water loss because we are not consciously aware of it, even

though it occurs continually in all living humans. The insensible water loss through the skin

occurs independently of sweating and is present even in people who are born without sweat

glands; the average water loss by diffusion through the skin is about 300 to 400 ml/day. This

loss is minimized by the cholesterol-filled cornified layer of the skin, which provides a barrier

against excessive loss by diffusion. When the cornified layer becomes denuded, as occurs with

extensive burns, the rate of evaporation can increase as much as 10-fold, to 3 to 5 L/day. For this

reason, burn victims must be given large amounts of fluid, usually intravenously, to balance fluid

loss. Insensible water loss through the respiratory tract averages about 300 to 400 ml/day. As

air enters the respiratory tract, it becomes saturated with moisture, to a vapor pressure of about

47 mm Hg, before it is expelled. Because the vapor pressure of the inspired air is usually less

than 47 mm Hg, water is continuously lost through the lungs with respiration. In cold weather,

the atmospheric vapor pressure decreases to nearly 0, causing an even greater loss of water from

the lungs as the temperature decreases. This explains the dry feeling in the respiratory passages

in cold weather.

(2)Fluid Loss in Sweat. The amount of water lost by sweating is highly variable, depending on

physical activity and environmental temperature. The volume of sweat normally is about 100

ml/day, but in very hot weather or during heavy exercise, water loss in sweat occasionally

increases to 1 to 2 L/hour. This would rapidly deplete the body fluids if intake were not also

increased by activating the thirst mechanism.

(3)Water Loss in Feces. Only a small amount of water (100 ml/day) normally is lost in the

feces. This can increase to several liters a day in people with severe diarrhea.

Lecture 3

Physiology

Dr. Affan Ezzat

2

(4)Water Loss by the Kidneys. The remaining water loss from the body occurs in the urine

excreted by the kidneys. For example, urine volume can be as low as 0.5 L/day in a dehydrated

person or as high as 20 L/day in a person who has been drinking tremendous amounts of water.

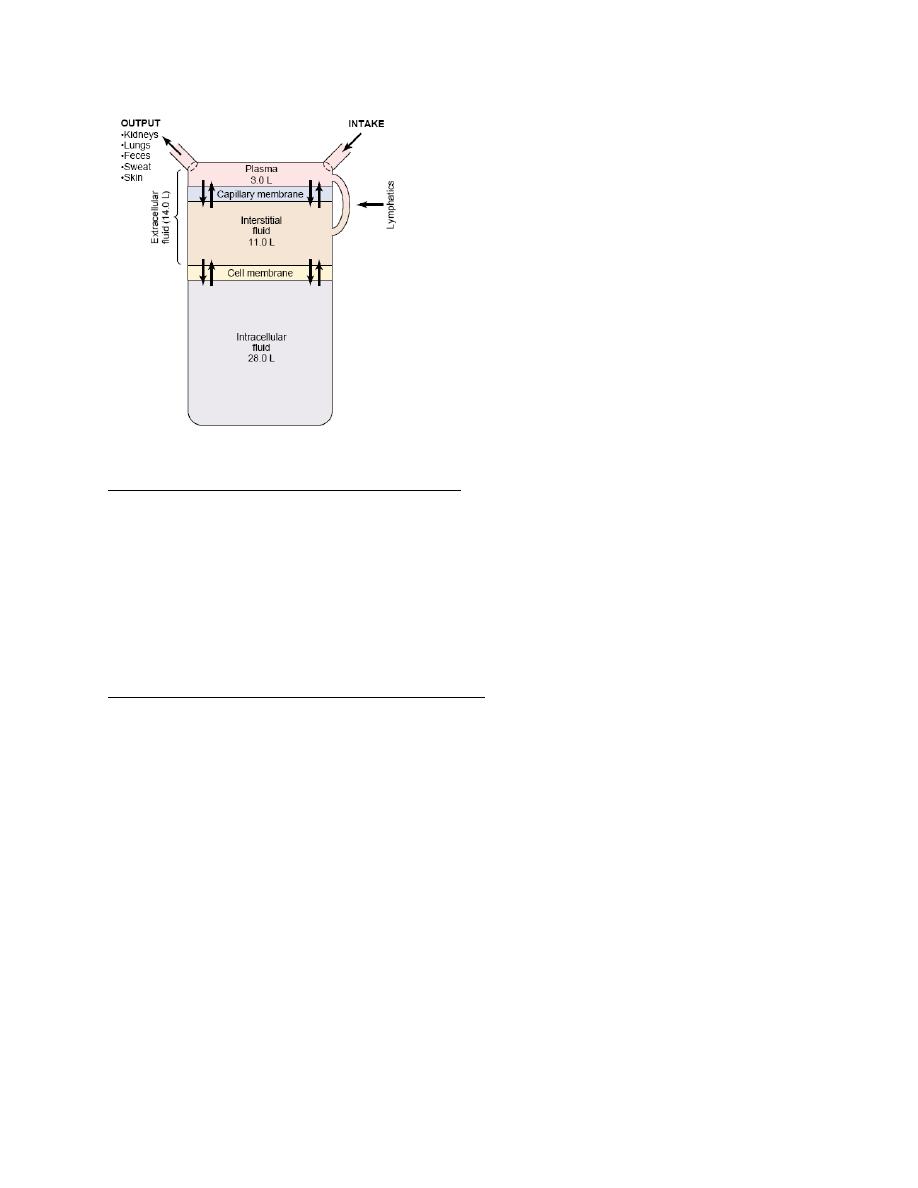

Body Fluid Compartments

The total body fluid is distributed mainly between two compartments: the extracellular fluid and

the intracellular fluid. The extracellular fluid is divided into the interstitial fluid and the blood

plasma.

There is another small compartment of fluid that is referred to as transcellular fluid; this

compartment includes fluid in the synovial, peritoneal, pericardial, and intraocular spaces, as

well as the cerebrospinal fluid; it is usually considered to be a specialized type of extracellular

fluid. All the transcellular fluids together constitute about 1 to 2 liters.

In the average 70-kilogram adult human, the total body water is about 60 per cent of the body

weight, or about 42 liters. This percentage can change, depending on age, gender, and degree of

obesity. As a person grows older, the percentage of total body weight that is fluid gradually

decreases. This is due in part to the fact that aging is usually associated with an increased

percentage of the body weight being fat, which decreases the percentage of water in the body.

Because women normally have more body fat than men, they contain slightly less water than

men in proportion to their body weight.

Intracellular Fluid Compartment

About 28 of the 42 liters of fluid in the body are inside the 75 trillion cells and are collectively

called the intracellular fluid. Thus, the intracellular fluid constitutes about 40 per cent of the

total body weight in an “average” person. The fluid of each cell contains its individual mixture of

different constituents, but the concentrations of these substances are similar from one cell to

another.

Extracellular Fluid Compartment

All the fluids outside the cells are collectively called the extracellular fluid. Together these fluids

account for about 20 per cent of the body weight, or about 14 liters in a normal 70-kilogram

adult. The two largest compartments of the extracellular fluid are the interstitial fluid, which

makes up more than three fourths of the extracellular fluid, and the plasma, which makes up

almost one fourth of the extracellular fluid, or about 3 liters. The plasma is the noncellular part

of the blood; it exchanges substances continuously with the interstitial fluid through the pores of

the capillary membranes. These pores are highly permeable to almost all solutes in the

extracellular fluid except the proteins. Therefore, the extracellular fluids are constantly mixing,

so that the plasma and interstitial fluids have about the same composition except for proteins,

which have a higher concentration in the plasma.

Blood Volume

Blood contains both extracellular fluid (the fluid in plasma) and intracellular fluid (the fluid in

the red blood cells). However, blood is considered to be a separate fluid compartment because it

is contained in a chamber of its own, the circulatory system. The blood volume is especially

important in the control of cardiovascular dynamics. The average blood volume of adults is

about 7 per cent of body weight, or about 5 liters. About 60 per cent of the blood is plasma and

40 per cent is red blood cells, but these percentages can vary considerably in different people,

depending on gender, weight, and other factors.

Lecture 3

Physiology

Dr. Affan Ezzat

3

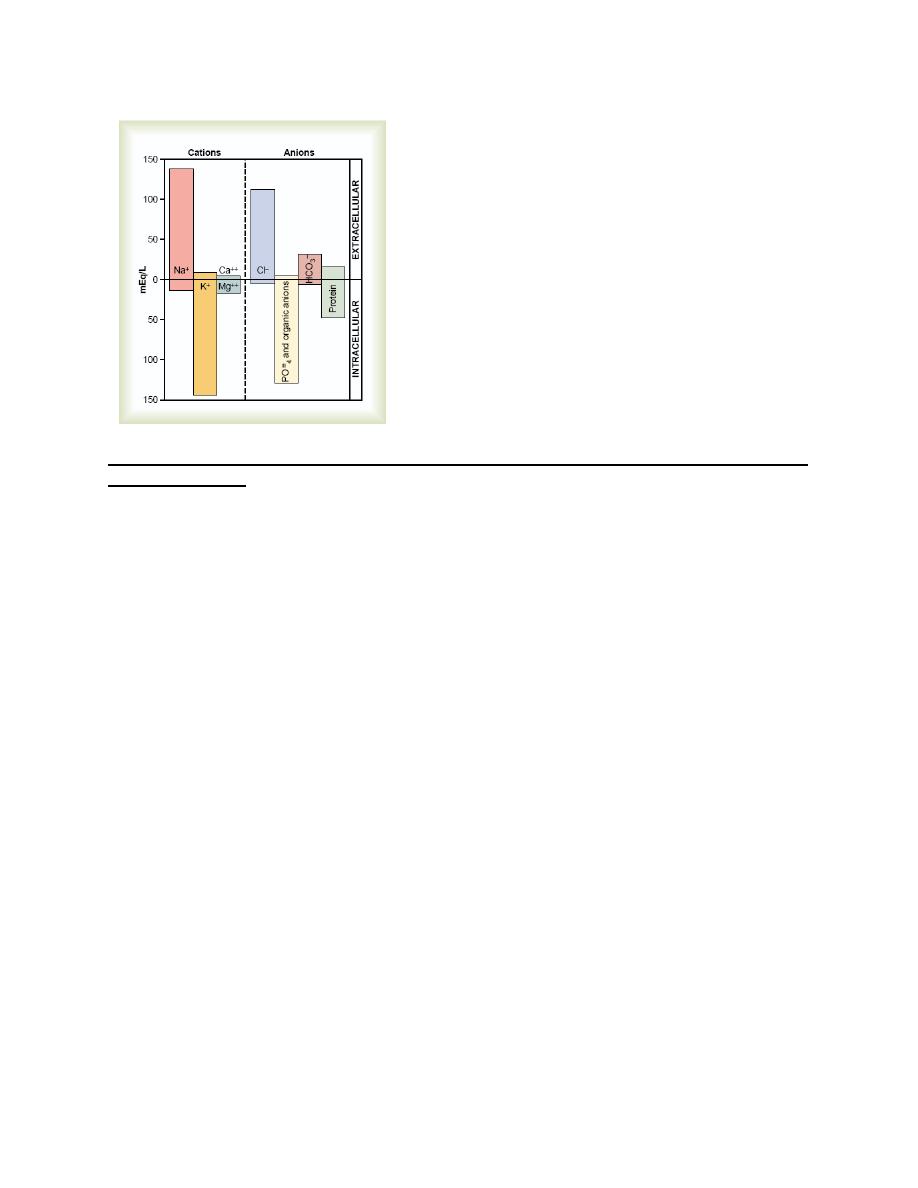

Important Constituents of Extracellular Fluid

Because the plasma and interstitial fluid are separated only by highly permeable capillary

membranes, their ionic composition is similar. The most important difference between these two

compartments is the higher concentration of protein in the plasma.

The extracellular fluid, including the plasma and the interstitial fluid, contains large amounts of

sodium and chloride ions, reasonably large amounts of bicarbonate ions, but only small

quantities of potassium, calcium, magnesium, phosphate, and organic acid ions. This allows

the cells to remain continually bathed in a fluid that contains the proper concentration of

electrolytes and nutrients for optimal cell function.

Important Constituents of the Intracellular Fluid

The intracellular fluid is separated from the extracellular fluid by a cell membrane that is highly

permeable to water but not to most of the electrolytes in the body. The intracellular fluid contains

large amounts of potassium and phosphate ions plus moderate quantities of magnesium and

sulfate ions, all of which have low concentrations in the extracellular fluid. Also, cells contain

large amounts of protein, almost four times as much as in the plasma. In contrast to the

extracellular fluid, it contains only small quantities of sodium and chloride ions and almost no

calcium ions.

Lecture 3

Physiology

Dr. Affan Ezzat

4

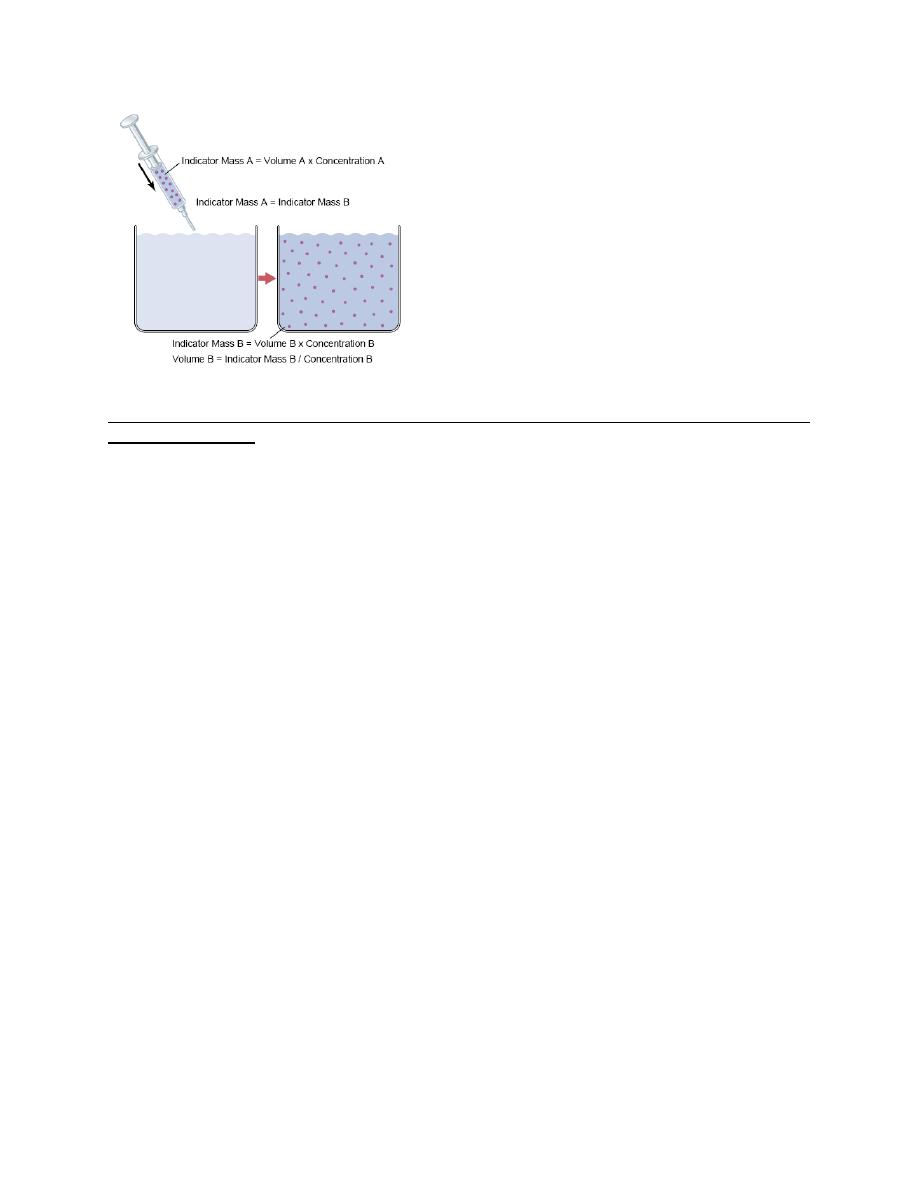

Measurement of Fluid Volumes in the Different Body Fluid Compartments—The Indicator

Dilution Principle

The volume of a fluid compartment in the body can be measured by placing an indicator

substance in the compartment, allowing it to disperse evenly throughout the compartment’s fluid,

and then analyzing the extent to which the substance becomes diluted. “indicator-dilution”

method of measuring the volume of a fluid compartment, which is based on the principle of

conservation of mass. This means that the total mass of a substance after dispersion in the fluid

compartment will be the same as the total mass injected into the compartment. A small amount

of dye or other substance contained in the syringe is injected into a chamber, and the substance is

allowed to disperse throughout the chamber until it becomes mixed in equal concentrations in all

areas. Then a sample of fluid containing the dispersed substance is removed and the

concentration is analyzed chemically, photoelectrically, or by other means. If none of the

substance leaks out of the compartment, the total mass of substance in the compartment (Volume

B × Concentration B) will equal the total mass of the substance injected (Volume A ×

Concentration A). By simple rearrangement of the equation, we can calculate the unknown

volume of chamber B as Note that all one needs to know for this calculation is (1) the total

amount of substance injected into the chamber and (2) the concentration of the fluid in the

chamber after the substance has been dispersed.

This method can be used to measure the volume of virtually any compartment in the body as

long as: (1) the indicator disperses evenly throughout the compartment.

(2) the indicator disperses only in the compartment that is being measured.

(3) the indicator is not metabolized or excreted.

Several substances can be used to measure the volume of each of the different body fluids.

Lecture 3

Physiology

Dr. Affan Ezzat

5

Regulation of Fluid Exchange and Osmotic Equilibrium Between Intracellular and

Extracellular Fluid

The distribution of fluid between intracellular and extracellular compartments is

determined mainly by the osmotic effect of the smaller solutes— especially sodium, chloride,

and other electrolytes— acting across the cell membrane. The reason for this is that the cell

membranes are highly permeable to water but relatively impermeable to even small ions such as

sodium and chloride. Therefore, water moves across the cell membrane rapidly, so that the

intracellular fluid remains isotonic with the extracellular fluid.

Basic Principles of Osmosis and Osmotic Pressure

Osmosis is the net diffusion of water across a selectively permeable membrane from a region of

high water concentration to one that has a lower water concentration. When a solute is added to

pure water, this reduces the concentration of water in the mixture. Thus, the higher the solute

concentration in a solution, the lower the water concentration. Further, water diffuses from a

region of low solute concentration (high water concentration) to one with a high solute

concentration (low water concentration). Because cell membranes are relatively impermeable to

most solutes but highly permeable to water (i.e., selectively permeable), whenever there is a

higher concentration of solute on one side of the cell membrane, water diffuses across the

membrane toward the region of higher solute concentration. Thus, if a solute such as sodium

chloride is added to the extracellular fluid, water rapidly diffuses from the cells through the cell

membranes into the extracellular fluid until the water concentration on both sides of the

membrane becomes equal. Conversely, if a solute such as sodium chloride is removed from the

extracellular fluid, water diffuses from the extracellular fluid through the cell membranes and

into the cells. The rate of diffusion of water is called the rate of osmosis.

Relation Between Moles and Osmoles. Because the water concentration of a solution depends

on the number of solute particles in the solution, a concentration term is needed to describe the

total concentration of solute particles, regardless of their exact composition. The total number of

particles in a solution is measured in osmoles. One osmole (osm) is equal to 1 mole (mol) (6.02

× 10

23

) of solute particles. Therefore, a solution containing 1 mole of glucose in each liter has a

concentration of 1 osm/L. If a molecule dissociates into two ions (giving two particles), such as

sodium chloride ionizing to give chloride and sodium ions, then a solution containing 1 mol/L

Lecture 3

Physiology

Dr. Affan Ezzat

6

will have an osmolar concentration of 2osm/L. Likewise, a solution that contains 1 mole of a

molecule that dissociates into three ions, such as sodium sulfate (Na

2

SO

4

), will contain 3 osm/L.

Thus, the term osmole refers to the number of osmotically active particles in a solution rather

than to the molar concentration. In general, the osmole is too large a unit for expressing osmotic

activity of solutes in the body fluids. The term milliosmole (mOsm), which equals 1/1000

osmole, is commonly used.

Osmolality and Osmolarity. The osmolal concentration of a solution is called osmolality when

the concentration is expressed as osmoles per kilogram of water; it is called osmolarity when it

is expressed as osmoles per liter of solution. In dilute solutions such as the body fluids. In most

cases, it is easier to express body fluid quantities in liters of fluid rather than in kilograms of

water.

Osmotic Pressure. Osmosis of water molecules across a selectively permeable membrane can

be opposed by applying a pressure in the direction opposite that of the osmosis. The precise

amount of pressure required to prevent the osmosis is called the osmotic pressure. Osmotic

pressure, therefore, is an indirect measurement of the water and solute concentrations of a

solution. The higher the osmotic pressure of a solution, the lower the water concentration and the

higher the solute concentration of the solution.

Relation Between Osmotic Pressure and Osmolarity. The osmotic pressure of a solution is

directly proportional to the concentration of osmotically active particles in that solution. This is

true regardless of whether the solute is a large molecule or a small molecule. For example, one

molecule of albumin with a molecular weight of 70,000 has the same osmotic effect as one

molecule of glucose with a molecular weight of 180. One molecule of sodium chloride, however,

has two osmotically active particles,Na+ and Cl–, and therefore has twice the osmotic effect of

either an albumin molecule or a glucose molecule. Thus, the osmotic pressure of a solution is

proportional to its osmolarity, a measure of the concentration of solute particles, for each

milliosmole concentration gradient across the cell membrane, 19.3 mm Hg osmotic pressure is

exerted.

Osmolarity of the Body Fluids. about 80 per cent of the total osmolarity of the interstitial fluid

and plasma is due to sodium and chloride ions, whereas for intracellular fluid, almost half the

osmolarity is due to potassium ions, and the remainder is divided among many other intracellular

substances. the total osmolarity of each of the three compartments is about 300 mOsm/L, with

the plasma being about 1 mOsm/L greater than that of the interstitial and intracellular fluids.

The slight difference between plasma and interstitial fluid is caused by the osmotic effects of the

plasma proteins, which maintain about 20 mm Hg greater pressure in the capillaries than in the

surrounding interstitial spaces.

Osmotic Equilibrium Is Maintained Between Intracellular and Extracellular Fluids

Large osmotic pressures can develop across the cell membrane with relatively small changes in

the concentrations of solutes in the extracellular fluid. For each milliosmole concentration

gradient of an impermeant solute (one that will not permeate the cell membrane), about 19.3 mm

Hg osmotic pressure is exerted across the cell membrane. If the cell membrane is exposed to

pure water and the osmolarity of intracellular fluid is 282 mOsm/L, the potential osmotic

pressure that can develop across the cell membrane is more than 5400 mm Hg. This

demonstrates the large force that can move water across the cell membrane when the intracellular

and extracellular fluids are not in osmotic equilibrium. As a result of these forces, relatively

small changes in the concentration of impermeant solutes in the extracellular fluid can cause

large changes in cell volume.