OSTEOGENESIS IMPERFECTA (BRITTLEBONES) (OI)

is one of the commonestof the genetic disorders of bone, with an

incidence of 1 in 20 000. Abnormal synthesis and

structural defects of type I collagen result in

(1) osteopenia,

(2) liability to fracture,

(3) laxity of ligaments,

(4) blue coloration of the sclerae

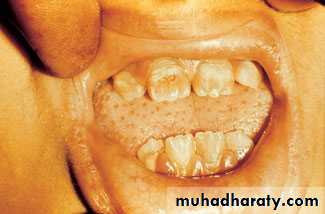

(5) dentinogenesis imperfecta(‘crumbling teeth’).

considerable variations in the severity of expression of these features and in the pattern of inheritance.

Clinical features

Which vary considerably, according tothe severity of the condition. The most striking abnormalityis the propensity to fracture, generally after minor trauma and often without much pain or swelling.

Classification:

OI TYPE I (MILD)• The commonest variety; over 50 per cent of all cases.

• Fractures usually appear at 1–2 years of age.

• Healing is reasonably good and deformities are not

marked.

Sclerae deep blue

• Teeth usually normal but some have dentinogenesis

imperfecta.

• Impaired hearing in adults.

• Quality of life good; normal life expectancy.

• Autosomal dominant inheritance.

OI TYPE II (LETHAL)

5–10 per cent of cases.

• Intra-uterine and neonatal fractures.

• Large skull and wormian bones.

• Sclerae grey.

• Rib fractures and respiratory difficulty.

• Stillborn or survive for only a few weeks.

• Most due to new dominant mutations; some autosomal recessive

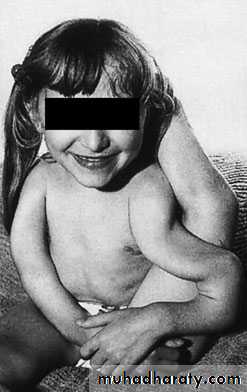

OI TYPE III (SEVERE DEFORMING) •

The ‘classic’, but not the most common, form of OI.• Fractures often present at birth.

• Large skull and wormian bones; pinched-looking

face.

• Marked deformities and kyphoscoliosis by 6 years.

• Sclerae grey, becoming white.

• Dentinogenesis imperfecta.

• Marked joint laxity.

• Respiratory problems.

• Poor quality of life; few survive to adulthood.

• Sporadic, or autosomal recessive inheritance.

OI TYPE IV (MODERATELY SEVERE). • Uncommon; less than 5 per cent of cases.

• Frequent fractures during early childhood.

• Deformities common.

• Sclerae pale blue or normal.

• Dentinogenesis imperfecta.

• Survive to adulthood with fairly good function.

• Autosomal dominent

Management

genetic manipulation is no more than a promise for the future.Conservative treatment is directed at preventing

Splintage for treating fractures whenthey occur. However, splintage should not be overdone as this may contribute further to the prevailing osteopenia.General measures to prevent recurrent trauma, maintain movement and encourage social adaptation are very important.

Children with severe OI may be treated medically with cyclical bisphosphonates to increase bone mineral density and reduce

the tendency to fracture. but immobilization must be kept to a

minimum.

,

Long-bone deformities are common, these may require operative correction, usually by 4 or 5 years of age. osteotomies are performed and the bone fragments are then realigned on a straight intra medullary

rod; the same effect can be achieved by closed osteoclasis.

The problem of the bone outgrowing the rod has

been addressed by using telescoping nails; however,

these carry a fairly high complication rate.

.

Spinal deformity is also common and is particularly difficult to treat.

Bracing is ineffectual and progressive

curves require operative instrumentation and spinalfusion after adolescence, fractures are much less common

• MUCOPOLYSACCHARIDOSES

The polysaccharide glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) form the side-chains of macromolecular proteoglycans, amajor component of the matrix in bone, cartilage,intervertebral discs, synovium and other connective tissues.

Defunct proteoglycans are degraded by lysosomal enzymes.

Deficiency of any of these enzymes

causes a hold-up on the degradative pathway. Partially degraded GAGs accumulate in the lysosomes in the liver, spleen, bones and other tissues, and spill over the blood and urine where they can be detected by suitable biochemical tests. Confirmation of theenzyme lack can be obtained by tests on cultured fibroblasts or leucocytes

Clinical Features

Depending on the specific enzyme deficiencyand the type of GAG storage, at least six clinical syndromes have been defined

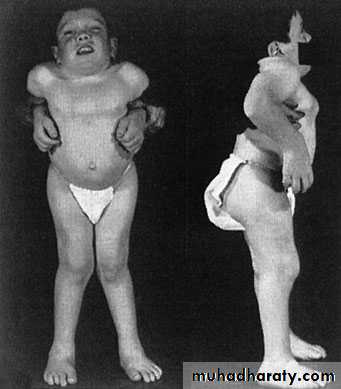

MORQUIO–BRAILSFORD SYNDROME

Development seems normal for the first year or two, although walking may be delayed. Thereafter the child beings to look dwarfed, with a moderate kyphosis,short neck and protuberant sternum. There is

marked joint laxity and progressive genu valgum.Suitable tests will reveal a conductive hearing loss. However, the face is unaffected and intelligence is normal.

X-rays of the spine show the typical ovoid, hypoplastic vertebral bodies, which end up abnormally

flat (platyspondyly) and peculiarly pointed anteriorly. Odontoid hypoplasia is usual.

A marked manubriosternal angle (almost 90°) is pathognomonic.

By the age of 5 years the femoral head epiphysesare underdeveloped and flat, and the acetabula

abnormally shallow. The long bones are of normal

width but the metacarpals may be short and broad,

and pointed at their proximal ends

Management

There is, as yet, no specific treatment for the

mucopolysaccharide disorder. However, enzyme

replacement and gene manipulation are possible in

the future.

Bone marrow transplantation has been used for the

last 20–30 years; when successful it halts progression

of CNS disease and some of the clinical features of the

condition but it cannot reverse neurological damage

that has already developed and it does not prevent

progression of bone and joint disease.

Enzyme replacement therapy is successful in mild cases of MPS

but it does not cross the blood-brain barrier.

Morquio’s syndrome presents several orthopaedic

problems.

Genu valgum may need correction by femoral osteotomy, though this should be delayed till growth has cease.

Coxa valga and subluxation of the hips, if symmetrical, may cause little disability;

unilateral subluxation may need femoral or acetabularosteotomy.

Atlantoaxial instability may threaten the

cord and require occipitocervical fusion.All the‘spondylodysplasias’ carry a risk of atlantoaxial subluxation during anaesthesia and intubation, and special precautions are needed during operation.