Pneumonia

Dr.Abdulla Al-farttoosi

OBJECTIVES

•

To define pneumonia .

•

To determine methods of its classification

•

To describe its epidemiology.

•

To describe Community Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) and its causes and

types.

•

To identify factors that predispose to pneumonia.

•

To recognize Clinical features of CAP.

•

To revise characteristic features of the common causes of CAP.

•

To asses and investigate a case of CAP.

•

To evaluate lines of management of CAP.

•

To recognize complications of CAP.

•

Pneumonia is defined as an acute

respiratory illness associated with recently

developed

radiological

pulmonary

shadowing which may be segmental, lobar

or multilobar.

•

Pneumonia

is

an

infection

of

the

pulmonary parenchyma.

•

Not a single disease, but a group of

specific infection, each having different

epidemiology,

pathogenesis,

clinical

manifestations and clinical course.

CLASSIFICATION:

•

Aetiology.

•

Morphological class. - Bronchopneumonia

vs. lobar pneumonia(

'

Lobar

:homogeneous

consolidation of one or more lung lobes, often with associated

pleural inflammation;

bronchopneumonia

:more patchy alveolar

consolidation associated with bronchial and bronchiolar

inflammation often affecting both lower lobes)

•

Community acquired vs hospital acquired

(nosocomial) infection.

•

The patient's immune status.

•

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP):

Outside of

hospital or extended-care facility.

•

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)

:

≥ 48 h from

admission.

•

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP)

:

≥ 48 h

from endotracheal intubation.

•

Health care-associated pneumonia (HCAP):

onset of

pneumonia as outpatients in patients infected with the

multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens usually associated

with HAP.

Epidemiology

•

Leading cause of death from an infectious

disease

•

6th leading cause of death in the US

•

Mortality ranges 2-30% in hospitalized

patients and averages 14%

•

Mortality if admitted to ICU nearly 50%

•

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)

remains a leading cause of death

worldwide despite improvement in patient

management.

•

Early recognition of lung infection and

prompt

initiation

of

adequate

antibiotherapy are crucial elements to

ensuring favourable outcomes.

•

Nonetheless, in a number of cases, death

occurs despite both these targets being

met. In these patients, possible excessive

inflammatory responses, as in sepsis and

septic shock, are believed to contribute to

unfavourable outcome.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

•

Pneumonia results from the proliferation of microbial

pathogens at the alveolar level and the host' s response to those

pathogens.

•

Microorganisms gain access to the lower respiratory tract in

several ways. The most common is by aspiration from the

oropharynx .Small-volume aspiration occurs frequently during

sleep (especiallyin the elderly) and in patients with decreased

levels of consciousness.

•

Many pathogens are inhaled as contaminated droplets.

•

Rarely pneumonia occurs via hematogenous spread

Host defense mechanisms

•

The hairs and turbinates of the nares capture larger

inhaled particles

•

The branching architecture of the tracheobronchial

tree .

•

Mucociliary clearance

•

The gag reflex and the cough mechanism.

•

The normal flora adhering to mucosal cells of the

oropharynx.

•

When these barriers are overcome or when

microorganisms are small enough to be inhaled to the

alveolar level, resident alveolar macrophages are

extremely efficient at clearing and killing pathogens.

•

Only when the capacity of the alveolar

macrophages to ingest or kill the

microorganisms is exceeded does clinical

pneumonia become manifest.

•

In that situation, the alveolar macrophages

initiate the inflammatory response to bolster

lower respiratory tract defenses.

•

The host inflammatory response, rather than

proliferation of microorganisms, triggers the

clinical syndrome of pneumonia.

Community Acquired

Pneumonia

•

Community Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) is

an acute infection of lung tissue that

develops outside of the hospital setting.

The most common bacterial cause of CAP

is Streptococcus pneumoniae .

Bacteria commonly enter the respiratory tract,

but do not normally cause pneumonia. When

pneumonia does occur, it is the result of:

1.A very virulent microbe

2.A large “dose” of bacteria

3.An impaired host defense mechanism

Factors that predispose to pneumonia

•

Cigarette smoking

•

Upper respiratory tract infections

•

Alcohol

•

Corticosteroid therapy

•

Old age

•

Recent influenza infection

•

Pre-existing lung disease

•

HIV

•

Indoor air pollution

•

•

Causative organism established in 60% CAP in

research setting, 20% in clinical setting

•

“Typical”:

– S. pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae,

Staphylococcus aureus, Group A streptococci,

Moraxella catarrhalis, anaerobes, and aerobic

gram-negative bacteria

•

“

Atypical”

- 20-28% CAP worldwide Legionella

spp, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila

pneumoniae, and C. psittaci

– Mainly distinguished from typical by not being

detectable on Gram stain or cultivable on

standard media

Clinical features

•

fever, rigors, shivering, headache and vomiting .

•

Dyspnea , cough with

mucopurulentsputum(occasional

haemoptysis)and Pleuritic chest pain

•

Upper abdominal pain

•

Less typical presentations may be seen at the

extremes of age.

•

signs:Crackles & bronchial breathing and

whispering pectoriloquy

Common clinical features of community-

acquired pneumonia

•

Streptococcus pneumoniae

•

Most common cause. Affects all age

groups, particularly young to middle-aged.

•

Sudden onset of fever, rigors, dyspnea,

bloody sputum production, chest pain,

tachycardia, tachypnea and abnormal

findings on lung exam

•

may be accompanied by herpes labialis

Staph aureus

•

Associated with debilitating illness and

often preceded by influenza.

•

Radiographic features include multilobar

shadowing, cavitation, pneumatocoeles

and abscesses.

•

Dissemination to other organs may cause

osteomyelitis, endocarditis or brain

abscesses. Mortality up to 30%

Klebsiella pneumoniae

•

More

common

in

men,

alcoholics,

diabetics, elderly, hospitalised patients,

and those with poor dental hygiene.

Predilection

for

upper

lobes

and

particularly liable to suppurate and form

abscesses. May progress to pulmonary

gangrene.

•

Haemophilus influenzae

:

More common

in old age and those with underlying lung

disease (COPD, bronchiectasis).

•

Pseudomonas

: not a typical cause of

CAP and usually associated in patients

who have prolonged hospitalization, have

been on broad-spectrum antibiotics, high-

dose steroids, structural lung disease

Mycoplasma pneumonia

•

Gram neg bacteria with no true cell wall

•

Frequent cause of CAP in adults + children

•

May be asymptomatic

•

Gradual onset

•

Objective abnormalities on physical exam are

minimal in contrast to the patients reported symptoms

•

Epidemics occur every 3-4 years, usually in autumn.

Rare complications include haemolytic anaemia,

Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema nodosum,

myocarditis, pericarditis, meningoencephalitis,

Guillain-Barré syndrome

Legionella pneumophila

•

Middle to old age.

•

Local epidemics around contaminated source,

e.g. cooling systems in hotels, hospitals. Person-

to-person spread unusual.

•

Some features more common, e.g. headache,

confusion, malaise, myalgia, high fever and

vomiting and diarrhoea.

•

Tends to be the most severe of the atypical

pneumonias

•

Laboratory abnormalities include

hyponatraemia, elevated liver enzymes,

hypoalbuminaemia and elevated creatine

kinase.

Chlamydia pneumoniae

•

Young to middle-aged.

•

Large-scale epidemics or sporadic; often

mild, self-limiting disease. Headaches and

a longer duration of symptoms before

hospital admission.

•

Usually diagnosed on serology

Differential diagnosis of

pneumonia

•

Pulmonary infarction

•

Pulmonary/pleural TB

•

Pulmonary oedema (can be unilateral)

•

Pulmonary eosinophilia (p. 713)

•

Malignancy: bronchoalveolar cell

carcinoma

•

Rare disorders: cryptogenic organising

pneumonia/

•

bronchiolitis obliterans organising

pneumonia (COP/BOOP)

Investigations

•

To exclude other conditions that mimic

pneumonia , assess the severity, and

identify the development of complications.

•

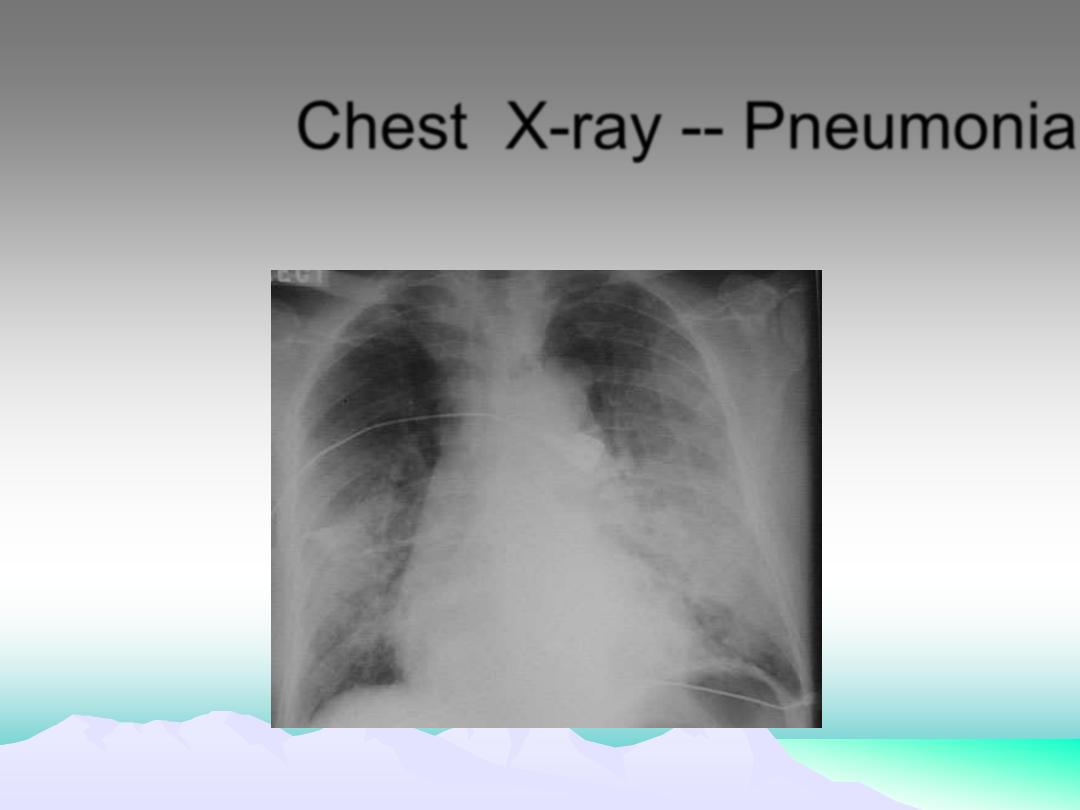

A

chest

X-ray

usually

provides

confirmation of the diagnosis.

Chest X-ray -- Pneumonia

Microbiological investigations

•

Severe disease

•

Notification(Legionella pneumophila)

•

In patients who do not respond to initial

therapy

•

provides useful epidemiological

information

•

Sputum:

direct smear by Gram and Ziehl-

Neelsen stains. Culture and antimicrobial

sensitivity testing

•

Blood culture

: frequently positive in

pneumococcal pneumonia

•

Serology

: acute and convalescent titres for

Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, Legionella,

and

viral infections. Pneumococcal antigen

detection in serum or urine

•

PCR

:

Mycoplasma

can be detected from

swab of oropharynx

•

Pulse oximetry

and arterial blood gas

•

The white cell count

: A very high (> 20

×

109/l) or low (< 4

× 109/l) white cell count

may be seen in severe pneumonia.

•

Urea

and electrolytes and liver function

tests

•

C-reactive protein

CURB-65

To assess severity and Determining Site of Care

• C

onfusion (

disorientation to person, place or time)

• U

rea (

BUN > 7 mmol/L)

• R

espiratory Rate (

RR > 30 breaths/minute)

• B

lood Pressure

(systolic< 90 mmHg-diastolic< 60 mm Hg)

• 65

(years of age or greater)

One point for each prognostic variable

0-1 treat as outpatient, 2 general inpatient admission,

3-5 intensive care admission

Management

•

Oxygen

•

Fluid balance

•

Antibiotic therapy.

•

Nutritional support

•

Treatment of pleural pain

•

Physiotherapy

Oxygen

•

All patients with tachypnoea, hypoxaemia,

hypotension or acidosis with the aim of

maintaining the PaO2

≥ 8 kPa (60 mmHg)

or SaO2

≥ 92%.

•

High concentrations (EXCEPT in COPD)

•

Assisted ventilation should be considered

at an early stage in those who remain

hypoxaemic despite adequate oxygen

therapy.

Antibiotic treatment for CAP

•

Uncomplicated CAP

•

Amoxicillin 500 mg 8-hourly orally

•

If patient is allergic to penicillin Clarithromycin

500 mg 12-hourly orally or

•

Erythromycin 500 mg 6-hourly orally

•

If Staphylococcus is cultured or suspected

Flucloxacillin 1-2 g 6-hourly i.v. plus

•

Clarithromycin 500 mg 12-hourly i.v.

•

If Mycoplasma or Legionella is suspected

Clarithromycin 500 mg 12-hourly orally or

i.v. or Erythromycin 500 mg 6-hourly orally

or i.v. plus

•

Rifampicin 600 mg 12-hourly i.v. in severe

cases

•

•

•

Severe CAP

•

Clarithromycin 500 mg 12-hourly i.v. or

•

Erythromycin 500 mg 6-hourly i.v.

plus

•

Co-amoxiclav 1.2 g 8-hourly i.v. or

•

Ceftriaxone 1-2 g daily i.v. or

•

Cefuroxime 1.5 g 8-hourly i.v. or

•

Amoxicillin 1 g 6-hourly i.v. plus

flucloxacillin 2 g 6-hourly i.v.

•

•

•

Patients with severe CAP should not

receive corticosteroids, unless shock that

requires vasopressor infusion is present.

•

In addition, corticosteroids should not be

given

in

case

of

influenza-related

respiratory distress.

•

patients exposed to NSAIDs during the

early stage of CAP had a worse

presentation

of

CAP,

more

pleuropulmonary

complications

and

required noninvasive ventilatory support

more often, such as high-flow oxygen

therapy

•

59- A patient was treated for right sided lobar pneumonia, he started to

improve but 5 days latter fever recurred with chills, night sweats and

chest pain in deep breathing, O/E dull chest percussion note on the right

side, chest X- ray showing D-shaped opacity. Which one of the followings

is the most likely cause?

•

A- Chylothorax

•

B- Empyema

•

C- Hemothorax

•

D- TB

•

E- Lung abscess

Complications of pneumonia

•

Para-pneumonic effusion-common

•

Empyema

•

Retention of sputum causing lobar collapse

•

DVT and pulmonary embolism

•

Pneumothorax, particularly with Staph. aureus

•

Suppurative pneumonia/lung abscess

•

ARDS, renal failure, multi-organ failure

•

Ectopic abscess formation (Staph. aureus)

•

Hepatitis, pericarditis, myocarditis,

meningoencephalitis

•

Pyrexia due to drug hypersensitivity

•

Indications for referral to ITU

•

CURB score of 4

–5,failing to respond

rapidly to initial management

•

Persisting hypoxia (

Pa

O

2

< 8 kPa (60

mmHg)), despite high concentrations of

oxygen

•

Progressive hypercapnia

•

Severe acidosis

•

Circulatory shock

•

Reduced conscious level

Hospital-acquired pneumonia

•

Refers to a new episode of pneumonia

occurring

at

least

2

days

after

admission to hospital. Older people are

particularly at risk, as are patients in

intensive care units, especially when

mechanically ventilated, in which case

the

term

ventilator-associated

pneumonia (VAP) is applied.

Health care-associated

pneumonia(HCAP

)

•

Refers to the development of

pneumonia in a person who has

spent at least 2 days in hospital

within the last 90 days, attended a

haemodialysis

unit,

received

intravenous antibiotics, or been

resident in a nursing home or other

long-term care facility.

Aetiology

•

When HAP occurs within 4-5 days of

admission (early-onset), the organisms

involved are similar to those involved in

CAP; however, late-onset HAP is more

often

attributable

to

Gram-negative

bacteria (e.g. Escherichia, Pseudomonas

and Klebsiella species), Staph. aureus

(including meticillin-resistant Staph. aureus

(MRSA)) and anaerobes.

Factors predisposing to hospital-acquired

pneumonia

•

Reduced host defences against

bacteria

•

Aspiration of nasopharyngeal or

gastric secretions

•

Bacteria introduced into lower

respiratory tract

•

Bacteraemia

Clinical features and investigations

•

HAP should be considered in any hospitalised or

ventilated patient who develops purulent sputum

,new radiological infiltrates, an otherwise

unexplained increase in oxygen requirement, a

core temperature > 38.3

°C, and a leucocytosis

or leucopenia. Appropriate investigations are

similar to those outlined for CAP, although

whenever possible, microbiological confirmation

should be sought. In mechanically ventilated

patients, bronchoscopy-directed protected brush

specimens or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) may

be performed.

Mangement

•

empirical antibiotic therapy :

•

Adequate Gram-negative cover by

•

a third-generation cephalosporin

+aminoglycoside

•

Or a monocyclic β-lactam (e.g. aztreonam) and

flucloxacillin.

•

or meropenem

•

MRSA is treated with intravenous vancomycin,

Suppurative pneumonia, aspiration

pneumonia and pulmonary abscess

•

These

conditions

are

considered

together, as their aetiology and clinical

features

overlap.

Suppurative

pneumonia

is

characterised

by

destruction of the lung parenchyma by

the inflammatory process

•

'pulmonary abscess' is usually

taken to refer to lesions in which

there is a large localised collection

of pus, or a cavity lined by chronic

inflammatory tissue, from which

pus has escaped by rupture into a

bronchus

.

risk factors

•

Inhalation of septic material during

operations or of vomitus during

anaesthesia or coma

•

Bulbar or vocal cord palsy

•

Stroke

•

Achalasia or oesophageal reflux

•

Alcoholism.

•

Local bronchial obstruction from a

neoplasm or foreign body.

•

Aspiration tends to localise to

dependent areas of the lung such

as the apical segment of the lower

lobe in a supine patient

•

Infections are usually due to a

mixture of anaerobes and aerobes

•

In a previously healthy lung, the

most likely infecting organisms are

Staph.

aureus

or

Klebsiella

pneumoniae

•

Injecting

drug-users

are

at

particular

risk

of

developing

haematogenous

lung

abscess,

often

in

association

with

endocarditis

affecting

the

pulmonary and tricuspid valves.

•

A non-infective form of aspiration

pneumonia-exogenous

lipid

pneumonia-may

follow

the

aspiration of animal, vegetable or

mineral oils.

Investigations

•

Radiological features :

•

lobar or segmental consolidation

or collapse.

•

abscesses are characterised by

cavitation and fluid level.

•

Sputum and blood culture.

Clinical features of

suppurative pneumonia

•

Cough productive of large

amounts of sputum which is

sometimes fetid and blood-stained

•

Pleural pain common

•

Sudden expectoration of copious

amounts of foul sputum occurs if

abscess ruptures into a bronchus

Clinical Signs

•

High remittent pyrexia

•

Profound systemic upset

•

Digital clubbing may develop quickly

(10-14 days)

•

Chest examination usually reveals

signs of consolidation; signs of

cavitation rarely found

•

Pleural rub common

•

marked weight loss

Mangement

•

Oral treatment with amoxicillin 500

mg 6-hourly is effective in many

patients. Aspiration pneumonia

can be treated with co-amoxiclav

1.2 g 8-hourly. If an anaerobic

bacterial infection is suspected

(e.g. from fetor of the sputum), oral

metronidazole 400 mg 8-hourly

should be given.

•

Parenteral

therapy

with

vancomycin or daptomycin can

also be considered.

•

Prolonged treatment for 4-6 weeks

may be required in some patients

with lung abscess

•

Physiotherapy

is

of

great

value,

especially when suppuration is present

in the lower lobes or when a large

abscess cavity has formed. In most

patients, there is a good response to

treatment,

and

although

residual

fibrosis

and

bronchiectasis

are

common sequelae, these seldom give

rise to serious morbidity. Surgery

should

be

contemplated

if

no

improvement occurs despite optimal

medical therapy.

Pneumonia

in the

immunocompromised patient

•

Patients immunocompromised by drugs

or disease are at high risk of pulmonary

infection. The majority of infections are

caused by the same pathogens that

cause

pneumonia

in

non-

immunocompromised individuals, but in

patients

with

more

profound

immunosuppression,unusual organisms,

or those normally considered to be of

low virulence or non-pathogenic, may

become 'opportunistic' pathogens

•

In addition to the more common

agents,

the

possibility

of

Gram-

negative

bacteria,

especially

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, viral agents,

fungi, mycobacteria, and less common

organisms

such

as

Nocardia

asteroides,

must

be

considered.

Infection is often due to more than one

organism.

Clinical Features

•

These typically include fever,

cough and breathlessness, but are

less specific with more profound

degrees of immunosuppression. In

general, the onset of symptoms

tends to be less rapid when caused

by opportunistic organisms such

as

Pneumocystis jirovecii

and in

mycobacterial infections, than with

bacterial infections

•

In

P. jirovecii

pneumonia, symptoms of

cough and breathlessness can be present

several days or weeks before the onset of

systemic symptoms or the appearance of

radiographic abnormality

Diagnosis

•

As many patients are too ill to undergo

Invasive investigations safely, 'induced

sputum' may offer a relatively safe method

of obtaining microbiological samples.

•

HRCT is useful in differentiating the likely

cause.

Management

•

The causative agent is frequently

unknown

and

broad-spectrum

antibiotic therapy is required, such

as:

•

a third-generation cephalosporin,

or

a

quinolone,

plus

an

antistaphylococcal antibiotic, or

•

an antipseudomonal penicillin plus

an aminoglycoside.

•

Thereafter

treatment

may

be

tailored according to the results of

investigations and the clinical

response.

Depending

on

the

clinical context and response to

treatment, antifungal or antiviral

therapies may be added.