1

D

D

I

I

A

A

B

B

E

E

T

T

E

E

S

S

M

M

E

E

L

L

L

L

I

I

T

T

U

U

S

S

د ﻋﻤﺮ ﻓﺎروق اﻟﻌﺰاوي

د ﻋﻤﺮ ﻓﺎروق اﻟﻌﺰاوي

L

L

E

E

C

C

5

5

7

7

2

2

0

0

1

1

4

4

2

2

0

0

1

1

5

5

2

Treatment of Diabetic Ketoacidosis

I. Admit

to The hospital; intensive-care unit

II. Confirm DIAGNOSIS by:

Ketonaemia > 3.0mmol/L or significant ketonuria (more than 2+ on standard urine sticks)

Blood glucose > 11 mmol/L or known diabetes mellitus

Bicarbonate (HCO3-) < 15 mmol/L and/or venous pH < 7.3

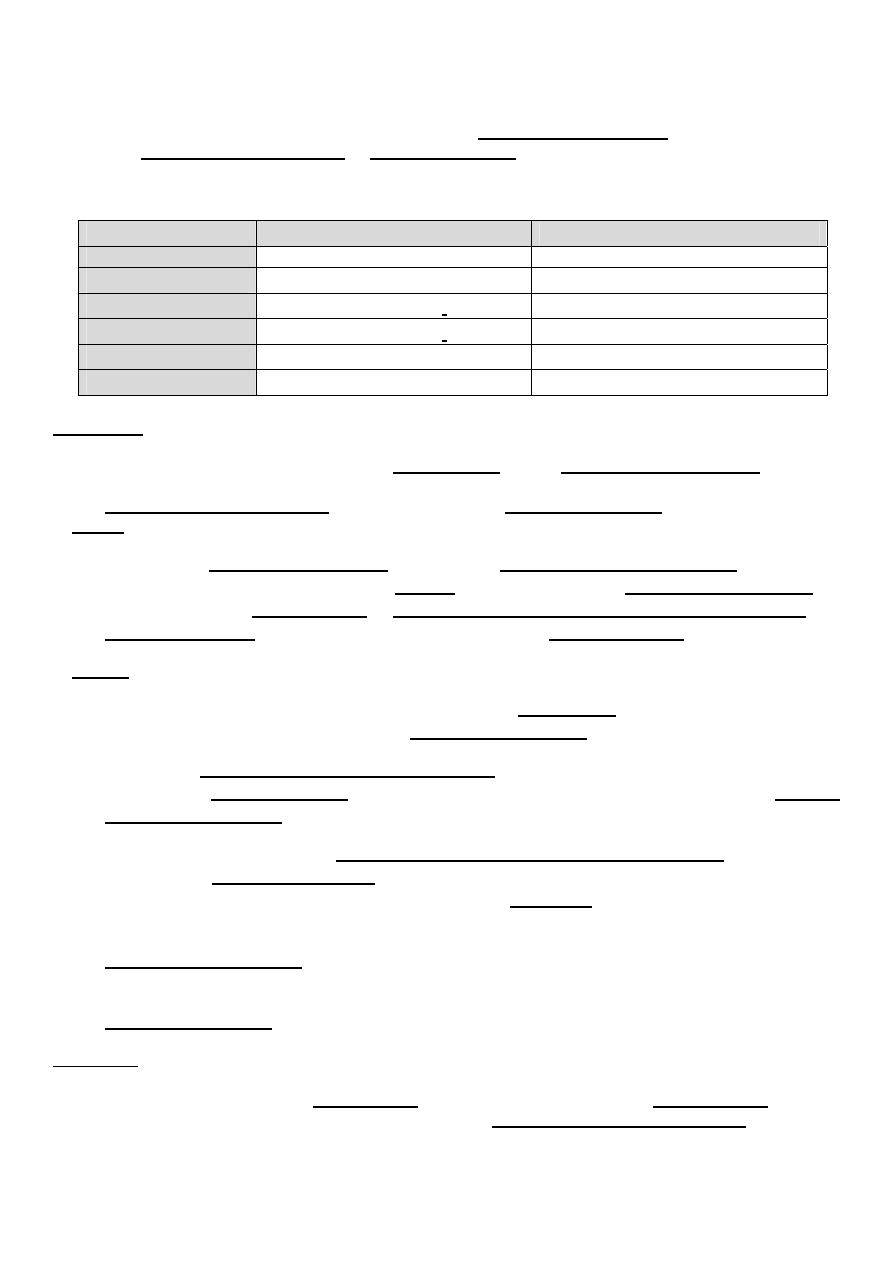

Average loss of fluid and electrolytes in an adult diabetic ketoacidosis of moderate severity

¾

Water : 5-7 liters

¾

Sodium : 500-1000 mmol/liter

¾

Chloride: 400-700 mmol/liter

¾

Potassium: 250-500 mmol/liter

¾

Phosphate: 50-180 mmol/liter

III. Fluid

Replacement:

The initial priority in the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis is the restoration of extracellular

fluid volume

This will

¾

Restore intravascular volume,

¾

Decrease counter regulatory hormones

¾

Decrease blood glucose level.

Many protocols are available defining the type and amount of fluids used in each hospital,

depending on their guidelines.

Then the severity of fluid and sodium deficits should be determined by:

¾

Clinical examination and orthostatic Bp.

¾

Serum osmolality and the corrected serum sodium concentration.

One of the protocols of fluid replacement is

1) If systolic BP > 90 mmHg,

Replace fluids: 2–3 L of 0.9% saline over first 1–3 h (15–20 ml/kg per hour); replacement of the

sodium and free water deficit is carried out over the next 24 h

Subsequently, When hemodynamic stability and adequate urine output are achieved,0.45%

saline at 250–500 ml/h

Change to 5% glucose and 0.45% saline at 150–250 mL/h when plasma glucose reaches 200-

250 mg/dL .

3

The use of 5% glucose allows continued insulin administration until ketonemia is controlled

and also helps to avoid iatrogenic hypoglycemia. Putting in mind that acidosis and ketosis

resolve more slowly than hyperglycemia.

2) If systolic BP < 90 mmHg, give 500 ml over 10–15 mins first then continue above.

IV. Insulin Therapy:

Also many protocols are available. The current recommendation is to give low-dose (short-

acting regular) Insulin which produces a liner fall in the glucose concentration

More rapid correction of hyperglycemia is avoided because it may increase the risk of cerebral

edema, which has a mortality rate of > 70 percent.

One of the protocols is

Administer short-acting insulin: IV bolus (0.1 units/kg), then 0.1 units/kg per hour by

continuous IV infusion.

Continue above until patient is stable, glucose goal is 8.3–13.9 mmol/L (150–250 mg/dL), and

acidosis is resolved, then Insulin infusion may be decreased to 0.05 units/kg per hour.

Long-acting insulin, in combination with SC short-acting insulin, should be administered as

soon as the patient resumes eating, this allow for overlap in insulin infusion and SC insulin

injection. Even relatively brief periods of inadequate insulin administration in this transition

phase may result in DKA relapse so NEVER stop IV insulin until SC starts to work.

V. During that time

¾

Measure glucose every 1–2 h;

¾

Measure electrolytes (especially K

+

, bicarbonate, phosphate) and anion gap every 4 h for

first 24 h.

¾

Monitor blood pressure, pulse, respirations, mental status, fluid intake and output every

1–4 h.

VI. Potassium Therapy:

Although the typical potassium deficit in diabetic ketoacidosis is 3–5 mmol/kg (3–5 meq/kg].

most patients are hyperkalemic at the time of diagnosis because of the effects of

¾

Insulin deficiency,

¾

Hyperosmolality,

¾

Academia.

Then during treatment many factors will lead to hypokalemia. These include

¾

Insulin-mediated potassium transport into cells,

¾

Resolution of the acidosis (which also promotes potassium entry into cells),

¾

Urinary loss of potassium salts of organic acids.

4

So potassium repletion should commence as soon as

adequate urine output

and the

initial

serum potassium level is not elevated

,

¾

If potassium level is elevated then potassium repletion should be delayed until the

potassium falls into the normal range.

¾

If the serum potassium is greater than 3.3 meq/L but less than 5.5 meq/L, 20-30 meq/L of

potassium infusion at a rate of 10 meq/h can be given.

¾

When the serum potassium level is less than 3.3 meq/L (3.3 mmol per L), the

administration 40–80 meq/h of potassium under close monitoring.

¾

The goal is to maintain the serum potassium at >3.5 mmol/L (3.5 meq/L).

VII. Bicarbonate Therapy:

In general, supplemental bicarbonate therapy is no longer recommended for patients with

diabetic ketoacidosis, Bicarbonate administration and rapid reversal of acidosis may impair

cardiac function, reduce tissue oxygenation, promote hypokalemia and increase risk of

cerebral edema esp. in children.

Insulin administration inhibits ongoing lipolysis and ketone production and also promotes the

regeneration of bicarbonate.

However, in the presence of severe acidosis (arterial pH <6.9), the ADA advises bicarbonate [50

mmol/L (meq/L) of sodium bicarbonate in 200 ml of sterile water with 10 meq/L KCl per hour for

2 h until the pH is >7.0].

VIII. Phosphate Therapy:

Osmotic diuresis and phosphate reentry to intracellular compartment during insulin therapy

may lead to mild-moderate reductions in the serum phosphate concentration.

Complications of hypophosphatemia are uncommon, So no clinical benefit for phosphate

replacement in the treatment of DKA

IX. Assess patient: What precipitated the episode (noncompliance, infection, trauma, infarction,

cocaine)? Initiate appropriate workup for precipitating event (cultures, CXR, ECG).and treat if

possible such as

Adding an appropriate

antibiotic

in the treatment regimen of DKA.

Complication of DKA

¾

Venous thrombosis,

¾

upper gastrointestinal bleeding,

¾

acute respiratory distress syndrome occasionally complicate DKA.

¾

Complication of DKA therapy is cerebral edema,

Prognosis of DKA

With appropriate therapy, the mortality rate of DKA is low (<1%) and is related more to

the precipitating event, such as infection or myocardial infarction.

5

HYPERGLYCEMIC HYPEROSMOLAR State OR HYPEROSMOLAR NON KETOTIC DIABETIC

COMA

Clinical Features

¾

Usually an elderly with type 2 DM (don’t occur in type 1 DM ),

¾

Several weeks history of Hyperglycemia leading to polyuria, weight loss,

¾

Diminished oral intake especially fluids

Leading to CNS features as: Mental Confusion / Drowsiness and lethargy / Seizure / Coma

Dehydration may also leads to increased viscosity, and thrombosis

Physical examination

Differs from DKA by

¾

Absence of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and Kussmaul respirations.

¾

More severe dehydration, hyperglycemia and hyperosmolality leading to hypotension,

tachycardia, and altered mental status

Precipitating Factors

Debilitating disease or social situation that compromises water intake as

¾

Myocardial infarction or stroke.

¾

Sepsis, pneumonia, and other serious infections.

¾

Tube-feeding with high protein and/or high carbohydrate formulas.

¾

Drugs as

Phenytoin / Steroid / Immune suppressive drugs / Diuretics.

All above are frequent precipitants and should be sought and treated.

Pathophysiology

¾

Relative insulin deficiency and inadequate fluid intake are the main underlying causes of

HHS.

¾

Hyperglycemia induces an osmotic diuresis that leads to intravascular volume depletion,

which is exacerbate the inadequate fluid replacement.

¾

The absence of ketosis in HHS is not understood, could be due to

1) The insulin deficiency is only relative and less severe than in DKA.

2) Lower levels of counterregulatory hormones and free fatty acids have been found in

HHS than in DKA.

3) It is also possible that the liver is less capable of ketone body synthesis.

4) The insulin /glucagon ratio does not in favor of ketogenesis.

¾

In contrast to DKA, acidosis and ketosis are absent or mild. A small anion-gap metabolic

acidosis may be present secondary to increased lactic acid.

Moderate ketonuria, if present, is secondary to starvation.

Laboratory Abnormalities and Diagnosis

¾

Marked hyperglycemia >55.5 mmol/L (1000 mg/dL),

¾

Hyperosmolality >350 mOsm/L,

6

¾

The measured serum sodium may be falsely normal or slightly low .

The corrected serum sodium is usually increased [add 1.6 meq to measured sodium for

each 5.6-mmol/L (100 mg/dL) rise in the serum glucose].

¾

Prerenal azotemia.

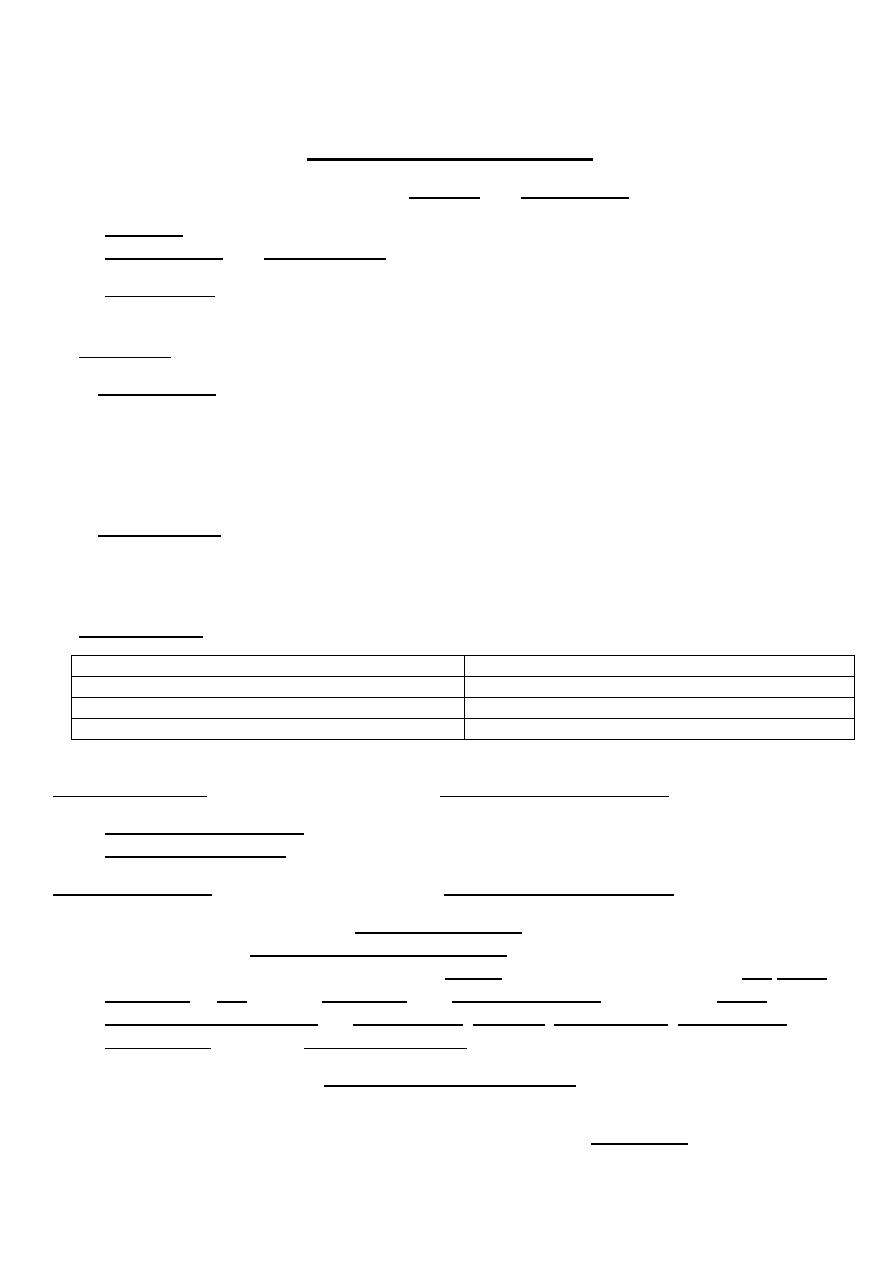

DKA

HHS

water deficit

9–10 L

5–7 L

Ketosis

Present

Absent

Bl Sugar

Usually less than 600

mg/dL

Usually more than 900

mg/dL

Osmolality

Usually less than 350

mOsm/L Usually more than 350

mOsm/L

Sodium

Usually Low

Usually High

Metabolic Acidosis Severe with anion gap

If present no or low anion gap

Treatment:

¾

Because the fluid deficit in HHS is accumulated over a period of days to weeks, the risk

of too rapid reversal may worsen neurologic function.

¾

Underlying or precipitating problems should be sought and treated.

I. Fluids

If the serum sodium > 150 mmol/L (150 meq/L), 0.45% saline should be used.

Free water deficit (which averages 9–10 L) should be reversed over the next 1–2 days

(infusion rates of 200–300 mL/h of hypotonic solution (0.45% saline initially, then 5%

dextrose in water) when the plasma glucose falls tom200–250 mg/dL .

II. Insulin

¾

Insulin regimen for HHS begins with an IV insulin bolus of 0.1 units/kg followed by IV

insulin at a constant infusion rate of 0.1 units/kg per hour.

¾

As in DKA, glucose should be added to IV fluid when the plasma glucose falls to 13.9–

16.7 mmol/L (200–250 mg/dL), and the insulin infusion rate should be decreased to 0.05–

0.1 units/kg per hour.

The insulin infusion should be continued until the patient has resumed eating and can be

transferred to a SC insulin regimen.

The patient should be discharged from the hospital on insulin, though some patients can

later switch to oral glucose-lowering agents.

III. Potassium

replacement is usually necessary and should be dictated by repeated

measurements of the serum potassium.

IV. Hypophosphatemia

treated by using KPO

4

and beginning nutrition.

Prognosis

The patient with HHS is usually older, more likely to have mental status changes, and more

likely to have a life-threatening precipitating factors with accompanying comorbidities.

Even with proper treatment, HHS has a substantially higher mortality rate than DKA (up to 15%

in some clinical series).

7

Chronic Complications of DM

Chronic complications can be divided into vascular and nonvascular complications.

1. Vascular complications are further subdivided into

Microvascular and Macrovascular .

2. Nonvascular complications include problems such as gastroparesis, infections, and skin

changes.

1. Vascular

Microvascular

¾

Eye disease

Retinopathy (nonproliferative /proliferative) / Macular edema

¾

Neuropathy

Sensory and motor (mono- and polyneuropathy) / Autonomic

¾

Nephropathy

Macrovascular

¾

Coronary heart disease

¾

Peripheral arterial disease

¾

Cerebrovascular disease

2. Nonvascular

Gastrointestinal (gastroparesis, diarrhea) Cataracts

and

Glaucoma

Genitourinary (uropathy/sexual dysfunction) Periodontal

disease

Dermatologic Hearing

loss

Infections

The microvascular complications of both type 1 and type 2 DM result from

¾

Chronic hyperglycemia.

¾

Genetic susceptibility also play role for developing particular complications.

The macrovascular complications of both type 1 and type 2 DM result from,

¾

Hyperglycemia by itself plays less conclusive role in its development.

¾

Other factors as (dyslipidemia and hypertension) also play important roles.

¾

Current recommendations for the use of aspirin in diabetic individuals is for any males

above 40y or any females above 50y, and before these ages if associated with a

cardiovascular risk factor (as hypertension, smoking, family history, albuminuria, or

dyslipidemia) if there is no contraindication.

Mechanisms of Complications

Chronic hyperglycemia is an important etiologic factor, the mechanism by

which it leads to such diverse cellular and organ dysfunction is unknown.

Four prominent theories have been proposed.

8

In general Growth factors appear to play an important role in some DM-related

complications, and their production is increased in most of these proposed theories.

Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) is increased locally in diabetic proliferative

retinopathy. Transforming growth factor (TGF) is increased in diabetic nephropathy and

stimulates basement membrane production of collagen and fibronectin by mesangial cells.

Other growth factors, such as platelet-derived growth factor, epidermal growth factor,

Insulin-like growth factor I, growth hormone, basic fibroblast growth factor, and even

insulin, have been suggested to play a role in DM-related complications.

Glycemic Control and Complications

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial for patients with type I DM (DCCT ) provided

definitive proof that reduction in chronic hyperglycemia can prevent many of the

complications of type 1 DM.

Improvement of glycemic control at any A

1C

level (what ever the reduction was) reduces

¾

Nonproliferative and proliferative retinopathy (47% reduction),

¾

Microalbuminuria (39% reduction),

¾

Clinical nephropathy (54% reduction),

¾

Neuropathy (60% reduction).

¾

While there was a nonsignificant reduction of macrovascular events during the trial

The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study for patients with type 2 DM (UKPDS)

demonstrated that each percentage point reduction in A

1C

was associated with a 35% reduction

in microvascular complications.

But didn’t reduce (nor worsen) cardiovascular mortality rate, but was associated with reduced

triglycerides and increased HDL.

One of the major findings of the UKPDS was that strict blood pressure control to <130/80

mmHg significantly reduced both macro- and microvascular risk of DM type 2 -related death,

stroke, retinopathy, and heart failure (between 32 and 60%).

The benefit of blood pressure control was greater than the benefit of glycemic control.

So the goal of therapy is to achieve an A

1C

level as close to normal as possible, without

subjecting the patient to risk of hypoglycemia, strict control of blood pressure and

dyslipidemia.

The disadvantage of achieving an A

1C

level as close to normal as possible was:

1. Weight gain.

2. Hypoglycemia.

Control is not indicated in:

1. Patients with impaired awareness of hypoglycemia.

2. Patients with MI or CVA history.

3. Elderly.

4. Children (pre-school age).

9

Eye Complications of Diabetes Mellitus

DM is the leading cause of blindness between the ages of 20 and 74. It needs 4-7 years history

of

uncontrolled

DM2 to develop, usually late in the 1

st

decade or early in the in the 2

nd

decade

of DM.

Risk factor

¾

The longer the duration of DM2 the higher the chance to occur.

¾

Degree of glycemic control.

¾

Hypertension is also a risk factor.

¾

Genetic susceptibility

Classified into two stages: nonproliferative and proliferative.

Nonproliferative

¾

Microaneurysms

¾

Blot hemorrhages

¾

Cotton-wool spots

later it progress to

¾

Changes in venous vessel caliber

¾

More numerous microaneurysms

¾

More numerous hemorrhages.

Proliferative

¾

Neovascularisation

¾

Pre-retinal- hemorrhage

¾

Vitreous - hemorrhage.

¾

Fibrosis,

¾

Exudative - maculopathy.

¾

And ultimately retinal detachment.

Treatment

¾

The most effective therapy is prevention by Intensive glycemic and blood pressure

control which will delay the development or slow the progression of retinopathy in both

type 1 and type 2 DM.

¾

Retinal photocoagulation therapy when applied in early stages is very effective. So

regular fundoscopy is mandatory

¾

Stop smoking and alcohol.

¾

Proliferative retinopathy is usually treated with panretinal laser photocoagulation,

whereas macular edema is treated with focal laser photocoagulation.

¾

Vitrectomy is indicated in recurrent vitreous hemorrhage that does not clear.

Renal Complications of Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetic nephropathy is the leading cause of ESRD

Only 20–40% of patients develop nephropathy, so additional factors remain unidentified.

One known risk factor is a family history of diabetic nephropathy.

Microalbuminuria is an important early indicator of nephropathy,

¾

50% of individuals with microalbuminuria progress to macroalbuminuria over the next 10

years.

10

¾

50% of individuals reach ESRD in 7–10 years. Once macroalbuminuria develops, blood

pressure rises slightly and the pathologic changes are likely irreversible.

Microalbuminuria is defined as 30–299 mg/d in a 24-h collection or 30–299 g/mg creatinine in a

spot collection

Macroalbuminuria is defined as >300 mg/d in a 24-h collection or > 300 g/mg creatinine.

Type IV renal tubular acidosis (hyporeninemic hypoaldosteronism) may occur in type 1 or 2

DM. These individuals develop a propensity to hyperkalemia, which may be exacerbated by

medications [especially angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin

receptor blockers (ARBs)] so keep this in mind if hyperkalemia occur with these 1

st

line drugs.

Risk-factors to develop nephropathy include:

1. Poor control of blood glucose.

2. Long duration of diabetes.

3. Presence of other microvascular complication.

4. Ethnicity (e.g. Asian-races).

5. Pre-existing hypertension.

6. Family history of diabetic nephropathy.

Pathological lesions are:

1. Minimal change glomerulonephritis

2. Focal / segmental glomerulosclerosis (Kimmelstiel - Wilson nodule: Is the

characteristic of diabetic glomerulosclerosis)

3. Diffuse glomerulosclerosis.

4. Acute & chronic pyelonephritis.

5. Acute papillary – necrosis.

Treatment: We can reduce the risk of nephropathic progression by:

1. Improved control of blood glucose, aggressive decrease of Blood pressure and

Hyperlipidemia should be treated aggressively

3. Starting ACE inhibitors or angiotensin type 2 receptors blockers, as Bp treatment and

used to reduce the progression from microalbuminuria to macroalbuminuria and the

associated decline in GFR that accompanies macroalbuminuria in individuals with type 1

or type 2 DM

4. Modest restriction of protein intake in patients with microalbuminuria (0.8–1.0 g/kg per

day) or macroalbuminuria (<0.8 g/kg per day).

5. Supportive with dialysis for end stage renal failure (ESRF).

6. Kidney transplantation

7. Insulin requirements may fall as the kidney is a site of insulin degradation.

Furthermore, many glucose-lowering medications (sulfonylureas and metformin) are

contraindicated in advanced renal insufficiency.

Diabetic Neuropathy

¾

Diabetic neuropathy occurs in 50% of individuals with long-standing (>10years) type 1

and type 2 DM. It may manifest as polyneuropathy, mononeuropathy, and/or autonomic

neuropathy.

Risk factors are BMI / smoking / cardiovascular disease / elevated triglycerides / and

hypertension.

11

Histopathology: Both myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibers are lost.

1. Axonal degeneration.

2. Thickening of Schwann cell basal lamina.

3. Patchy segmental demyelination.

Polyneuropathy

1. The most common form of diabetic neuropathy is distal symmetric polyneuropathy

usually sensory

Physical examination reveals sensory loss, loss of ankle reflexes, and abnormal position

sense.

Treated by {Tricyclic Antidepressant, Tegretol and Gabapentin.

2. Polyradiculopathy is a syndrome characterized by severe disabling pain in the

distribution of one or more nerve roots, may be accompanied by motor weakness.

Involvement of the lumbar plexus or femoral nerve may cause severe pain in the thigh or

hip and may be associated with muscle weakness in the hip flexors or extensors

(diabetic amyotrophy) is an e.g. Usually self-limited over 6–12 month.

Mononeuropathy dysfunction of isolated cranial or peripheral nerves) is less common than

polyneuropathy presents with pain and motor weakness in the distribution of a single nerve.

Involvement of the third cranial nerve is an e.g. and is heralded by diplopia. Physical

examination reveals ptosis and ophthalmoplegia with normal pupillary constriction to light.

Autonomic Neuropathy

Individuals with long-standing type 1 or 2 DM may develop signs of autonomic

dysfunction involving the,

Can involve multiple systems, including

A. CVS:

1. Postural hypotension is treated by {adequate salt intake, avoidance of dehydration

and diuretics, lower extremity support hose, fludrocortisone, clonidine, octreotide}.

2. Resting tachycardia and fixed heart rate.

3. sudden death

B. GIT:

1. Dysphagia.

2. Abdominal fullness which is diabetic gastroparesis due to parasympathetic

dysfunction and hyperglycemia , both impairs gastric emptying., treated by

{Metoclopramide, domperidone, erythromycin}.

3. Nocturnal diarrhea, alternating with constipation, Diabetic diarrhea is treated

symptomatically with loperamide and may respond to octreotide.

C. Genitourinary:

1. Diabetic cystopathy - U.T.I is treated by {intermittent self-catheterization}

2. Male Impotence, and retrograde ejaculation. Impotence (Erectile dysfunction) is

treated by:

¾

5 phosphodiesterase inhibitor as Sildenafil (Viagra) / Vacuum tumescence devices

/ Implanted penile prosthesis / Psychological counseling.

3. Female sexual dysfunction (reduced sexual desire, dyspareunia, reduced vaginal

lubrication).

12

D. Sudomotor: result from sympathetic nervous system dysfunction.

1. Gustatory sweating is treated by {Anticholinergics, antimuscarinic propantheline,

clonidine, topical antimuscarinic agent}

2. Nocturnal sweating without hypoglycemia.

3. Anhidrosis, of the feet leads fissures in the feet.

E. Vasomotor:

1. Cold feet.

2. Dependent edema.

3. Bullous formation

F. Pupillary:

1. Decreased pupil size.

2. Resistance to mydriatics.

3. Delayed or absent reflexes to light.

G. Diabetic foot:

The reasons for the increased incidence of Diabetic foot involve: Neuropathy/ abnormal

foot biomechanics / peripheral arterial disease / and poor wound healing.

Structural changes in the foot (hammertoe, claw toe deformity, prominent metatarsal

heads, Charcot joint) are due to motor and sensory neuropathy lead to abnormal foot

muscle mechanics.

Ulcers may be either neuropathic or vascular and most common site is the plantar

surface of the foot.

Prevention and Treatment of diabetic foot:

1. Check their feet daily and take precautions (footwear).

2. Ensure good glycemic - control.

3. Avoid weight - bearing.

4. Treat infection by appropriate use of antibiotics.

5. Angiographic study to check for vascular reconstruction where indicated.

6. limited amputation.

Long-Term Treatment of type 1 and type 2 DM

The goals of therapy for type 1 or type 2 DM are to

(1) Eliminate symptoms related to hyperglycemia,

(2) Reduce or eliminate the long-term microvascular and macrovascular complications of DM,

(3) Allow the patient to achieve as normal lifestyle as possible

To reach these goals, a target level of glycemic control should be individualized for each

patient, according to

¾

Patient's age,

¾

Presence and severity of complications of diabetes,

¾

Ability to recognize hypoglycemic symptoms,

¾

Presence of other medical conditions or treatments that might alter the response to

therapy,

(Patients who are old with any of the above don’t need strict control).

¾

Lifestyle and occupation (e.g., possible consequences of experiencing hypoglycemia on

the job)

13

¾

Ability to understand and implement a complex treatment regimen,

¾

Level of support available from family and friends.

¾

Availability of pharmacologic resources necessary to reach this

Goals

¾

A1C <7.0%

¾

Preprandial glucose 70–130 mg/dL

¾

postprandial glucose <180 mg/dL

¾

Blood pressure <130/80

¾

LDL <100 mg/dL

¾

HDL > 40 mg/dL men/50 mg/dL/women

¾

Triglycerides 150 mg/dL

How

¾

Education

¾

Nutrition

¾

Exercise

¾

Pharmacological drugs

¾

Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose

¾

Assessment of Long-Term Glycemic Control Measurement of glycated hemoglobin is

the standard method for assessing long-term glycemic control.

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

The care of individuals with type 2 DM must also include attention to the treatment of

conditions associated with type 2 DM (obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular

disease) and detection/management of DM-related complications

Pharmacologic approaches to the management of type 2 DM include, oral glucose-lowering

agents and/or insulin.

Glucose-lowering agents are subdivided to

Biguanides

Insulin Secretagogues,

Incretins Based Secretagogues,

Increase insulin sensitivity,

α

-Glycosidase Inhibitors

Bromocriptine

(Cycloset ONLY IS USED and not Parlodel)

Sodium glucose co transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2)

Biguanides

Metformin, represent the class of these agents,

Reduces hepatic glucose production and improves peripheral glucose utilization so slightly

lowers insulin levels, leading to decreased fasting plasma glucose

mainly

and improves

the lipid profile.

Promotes modest weight loss and do not cause hypoglycemia,

The initial starting dose of 500 mg once or twice a day can be increased to 1000 mg bid.

14

Side effects diarrhea, anorexia, nausea, metallic taste, lactic acidosis.

The major toxicity of metformin, lactic acidosis is very rare and can be prevented by careful

patient selection.

Metformin should not be used in patients with renal insufficiency [GFR < 60 mL/min Serum

creatinine >1.5 mg/dL (men) >1.4 mg/dL (women), Congestive Heart Failure [CHF), seriously

ill patients, any form of acidosis, liver disease, or severe hypoxemia, radiographic contrast

studies,

Vitamin B12 levels are 30% lower during metformin treatment so should be supplemented.

Insulin Secretagogues

Insulin secretagogues stimulate insulin secretion by interacting with the ATP-sensitive

potassium channel on the beta cell

A- Sulfonylureas

First-generation sulfonylureas (chlorpropamide, tolazamide, tolbutamide; have a longer

half-life, a greater incidence of hypoglycemia, more frequent drug interactions,

Second-generation Glyburide (Glibenclamide), Glimepiride and glipizide

sulfonylureas have a more rapid onset of action and better coverage of the postprandial

glucose rise than Metformin.

Glyburide require more than once-a-day dosing. Glimepiride and glipizide can be given in a

single daily dose.

Sulfonylureas reduce both fasting and postprandial glucose. Sulfonylureas Should be taken

before meals

Their use in individuals with significant hepatic or renal dysfunction is not advisable.

Weight gain, and hypoglycemia are common with sulfonylurea therapy, resulting from the

increased insulin levels and improvement in glycemic control.

B- Meglitinide (Repaglinide and nateglinide)

Are non sulfonylureas secretagogues, also interact with the ATP-sensitive K channel.

Because of their short half-life, these agents are given with each meal or immediately

before.

Weight gain, and hypoglycemia especially in elderly is possible .

Incretins Based Secretagogues

Enhance Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor signaling and amplify glucose-stimulated

insulin secretion

Do not cause hypoglycemia because of the glucose-dependent nature of incretin-stimulated

insulin secretion

15

A- GLP-1 agonist

An analogue of GLP-1, but unlike native GLP-1, which has a half-life of <5 min, differences

in the amino acid sequence (as Exenatide) or binding to albumin and plasma proteins

(as Liraglutide) render it resistant to the enzyme that degrades GLP-1, dipeptidyl peptidase

IV, or DPP-IV).

They act by

¾

Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion,

¾

Suppress glucagon,

¾

And slow gastric emptying.

Do not promote weight gain; in fact, most patients experience modest weight loss and

appetite suppression. Should not be used in patients taking insulin.

Side effects are nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, pancreatitis and reduced renal function

B- DPP-IV inhibitors

Inhibit degradation of native GLP-1. DPP-IV inhibitors promote insulin secretion in the

absence of hypoglycemia or weight gain,

Reduced doses should be given to patients with renal insufficiency

Increase insulin sensitivity (Thiazolidinediones)

¾

Reduce insulin resistance in peripheral tissue (muscles and adipose tissue) so decrease

insulin levels

¾

Promote a redistribution of fat from central to peripheral locations.

Associated with weight gain (2–3 kg), a small reduction in the hematocrit,

and a mild increase in plasma volume and may lead to peripheral edema and CHF.

These agents are contraindicated in patients with liver disease or CHF (class III or IV).

α

-Glycosidase Inhibitors

-Glucosidase inhibitors (acarbose) reduce postprandial hyperglycemia by delaying glucose

absorption; by inhibiting the enzyme that cleaves oligosaccharides into simple sugars in

the intestinal lumen.

Side effects diarrhea, flatulence, abdominal distention

Not used in individuals with inflammatory bowel disease, gastroparesis, or a serum

creatinine >2 mg/dL.

Is not as potent as other oral agents in lowering the A1C but is unique because it reduces

the postprandial glucose rise even in individuals with type 1 DM.

Bromocriptine

L

Cycloset is a dopamine receptor agonist. The mechanism by which

Cycloset improves glycemic control is unknown. Morning administration of Cycloset

improves glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes without increasing plasma

insulin concentrations.

16

SGLT2 inhibitors

A protein called sodium-glucose co transporter 2 (SGLT2) in the

proximal tubule plays an important role in renal glucose reabsorption.

Suppressing the activity of SGLT2 in the body inhibits renal glucose reabsorption, thereby

increasing the excretion of excess glucose. SGLT2 inhibitors do not stimulate insulin

secretion and therefore have a low risk for hypoglycemia, lead to clinically significant

weight loss, and act as osmotic diuretics, resulting in a lowering of BP.

General Consideration

(1) insulin secretagogues, biguanides, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and thiazolidinediones, all

improve glycemic control to a similar degree (1–2% reduction in A1C) and are more

effective than -glucosidase inhibitors and DPP-IV inhibitors.

(2) No clinical advantage to one class of drugs has been demonstrated, and any therapy

that improves glycemic control is used.

(3) Not all agents are effective in all individuals with type 2 DM (primary failure or secondary

failure esp. Sulfonylureas)

(4) Biguanides /

α

-glucosidase inhibitors / GLP-1 receptor agonists / DPP-IV inhibitors,/ and

thiazolidinediones do not cause hypoglycemia.

(5) Most individuals will eventually require treatment with more than one class of oral

glucose-lowering agents or insulin, reflecting the progressive nature of type 2 DM;

(6) A reasonable treatment algorithm for initial therapy uses

metformin

as initial therapy

because of its efficacy, known side-effect profile, and relatively low cost

(7) If adequate control is not achieved add another agent (based on reassessment of the A

1C

every 3 months), a third oral agent or basal insulin should be added if adequate control

is also not achieved

(8) Treatment with insulin becomes necessary as type 2 DM enters the phase of sever

insulin deficiency (as seen in long-standing DM) and is signaled by inadequate glycemic

control with one or more oral glucose-lowering agents. Insulin alone or in combination

should be used in these patients.

Bariatric surgery

For markedly obese individuals with type 2 diabetes has shown considerable promise—

sometimes with resolution of the diabetes or major reductions in the needed dose of glucose-

lowering therapies. Usually considered in individuals with DM and a BMI >35 kg/m

2

.

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

Insulin is the

only definite treatment.

Insulin regimens

The regimens used are those that try to mimic physiologic insulin secretion.

17

Insulin used are

-Basal insulin is essential for regulating glycogen breakdown, gluconeogenesis, lipolysis,

and ketogenesis, e.g. Human NPH (Neutral Protamine Hagedorn),glargine and detemir last 2

are human analogues) are most commonly used.

-Rapid or short acting insulin is for meals carbohydrate intake to promote glucose

utilization and storage. e.g. Human actrapid, or human analogues (insulin aspart, glulisine

or lispro) are used.

¾

Multiple daily injections (MDI),

¾

insulin infusion devices

¾

Multiple daily injections (MDI),

A- Basal insulin glargine or detemir to provide basal insulin coverage and three preprandial

shots of glulisine, lispro, or insulin aspart to provide glycemic coverage for each meal.

In general, individuals with type 1 DM requires a dose of 0.5–1 U/kg per day of insulin

divided to 50% as basal insulin and the other 50% into three preprandial shots.

B

- Two shots of long-acting insulin (NPH) and one of the short-acting insulin.

Two-thirds of the total daily insulin dose (0.5–1 U/kg per day) in the morning subdivided to

(two-thirds as long-acting insulin and one-third as short-acting)

The One-third left of the total daily insulin dose given before the evening meal (with

approximately one-half given as long-acting insulin and one-half as short-acting).

Although it is simple and effective at avoiding severe hyperglycemia, it does not generate

near-normal glycemic control in individuals with type 1 DM.

C- Many other regimens are also available

Insulin Pumps

Computerized devices that deliver insulin in two ways: continuous steady measured Insulin

administration as basal / and a bolus pulses at your order at each meal.

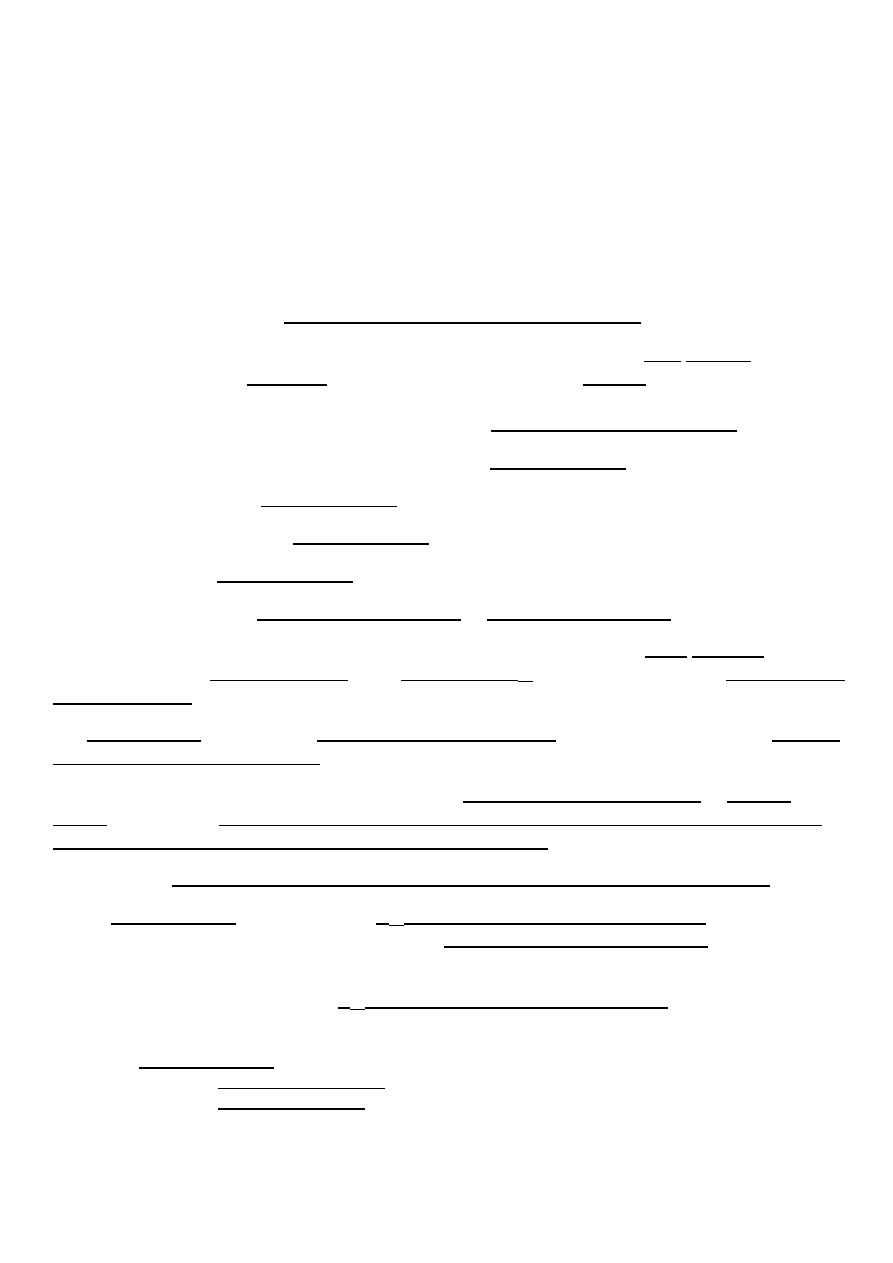

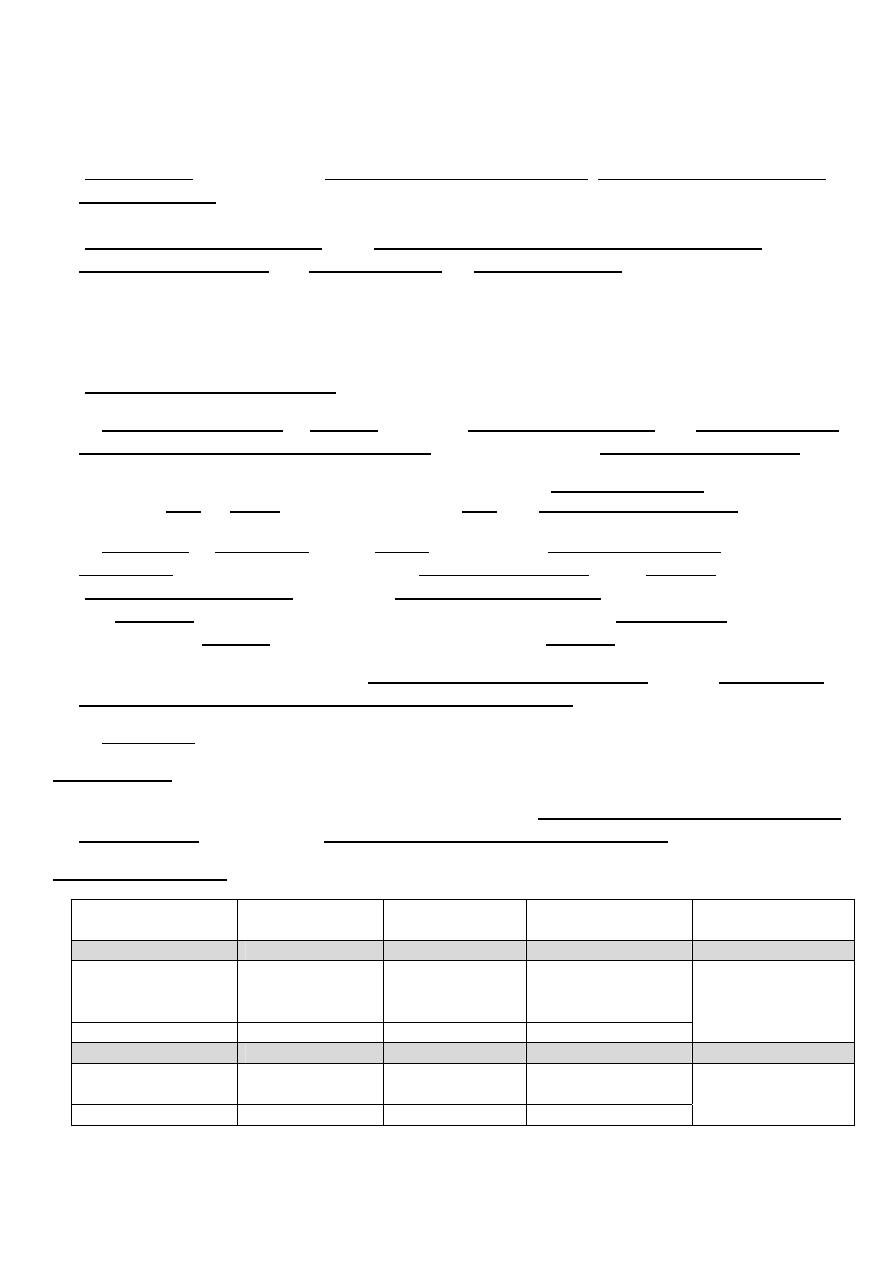

Characters of Insulin

Onset

Peak

Duration

of

action

Route of

administration

Short-acting

Aspart /

Lispro /

Glulisine

<0.25 hrs

0.5–1.5 hrs

3–4hrs

SC, IM, IV

Regular

0.5–1.0 hrs

2–3 hrs

4–6 hrs

Long-acting basal

Detemir /

Glargine

1–4 hrs

No peak

24hrs

SC only

NPH

1–4 hrs

6–10 hrs

10–16 hrs

18

Insulin combinations Some of the Insulin manufacturers premix the Insulin as in the following

formulations e.g.

¾

protamine lispro 75/25 =75% long acting and 25% short-acting or

¾

protamine lispro 50/50 =50% long acting and 50% short-acting.

¾

protamine aspart 70/30 =70% long acting and 30% short-acting.

Onset /<0.25 hrs Peak /1.5 hrs Duration /Up to 10–16 hrs

¾

70% NPH, 30% regular =70% long acting and 30% short-acting.

Onset /0.5–1 hrs Peak /Dual Duration /10–16 hrs

Combination (premixed) insulin formulations above are more convenient for those who are

unable to mix insulin for any reason as elderly, bad vision, children, unable to understand

how to mix,

BUT

do not allow independent adjustment of short-acting and long-acting

activity.

Mixing of Insulin of unmixed insulin is possible but remember

(1) Mix the different insulin formulations in the syringe immediately before injection (inject

within 2 min after mixing);

(2) Do not store insulin as a mixture;

(3) Do not mix insulin glargine or detemir with other insulin

Hypoglycemia

Causes

1. Treatment of DM. Insulin and insulin secretagogues.

Exogenous insulin causes hypoglycemia with low C-peptide levels, whereas insulin

secretagogue causes hypoglycemia with increased C-peptide levels

2. Drugs as Alcohol-abuse/angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin

receptor antagonists/adrenergic receptor antagonists/quinolone antibiotics/

indomethacin/quinine/and sulfonamides

3. Critical illness Hepatic, renal or cardiac failure or Sepsis

4. Endogenous hyperinsulinism as Insulinoma /Functional beta-cell disorders /Post–gastric

bypass postprandial hypoglycemia

5. Hormone deficiency as Addison’s disease or hypopituitarism /Glucagon.

6. Non–islet cell tumor

7. Accidental, or surreptitious

(done in a secret way) hypoglycemia

19

8. Pseudohypoglycemia is an artifactual, e.g., the result of continued glucose metabolism

by the formed elements of the blood, particularly in the presence of leukocytosis,

erythrocytosis, or thrombocytosis, or if separation of the serum from the formed elements

is delayed.

Diagnosis:

Rests on Whipple's triad:

1. Symptoms of hypoglycemia.

2. Low plasma glucose concentration < 55 mg/dL

3. Relief of symptoms after glucose administration.

The diagnostic strategy is to obtain measurements of plasma glucose, insulin, C-peptide,

proinsulin (if high levels means the natural insulin is increased) , hydroxybutyrate

concentrations and to screen for circulating oral hypoglycemic agents

Clinical features:

¾

Neuroglycopenic symptoms of hypoglycemia

Are the direct result of central nervous system (CNS) glucose deprivation

(The brain

cannot synthesize glucose or store more than a few minutes supply of glycogen and

therefore requires a continuous supply of glucose). They include behavioral changes,

confusion, fatigue, seizure, loss of consciousness, and, if hypoglycemia is severe and

prolonged, death.

¾

Neurogenic (or autonomic) symptoms They include

Adrenergic symptoms (mediated largely by norepinephrine released from sympathetic

postganglionic neurons but perhaps also by epinephrine released from the adrenal

medullae) such as pallor, palpitations, indrease Bp, tremor, and anxiety.

Cholinergic symptoms (mediated by acetylcholine released from sympathetic

postganglionic neurons) such as cold sweating, hunger, and paresthesias.

Prognosis Of Hypoglycemia

It can cause significant morbidity & can be lethal if severe & prolonged. An estimated 6–10% of

people with T1DM die as a result of hypoglycemia.

Insulinomas

Uncommon primary beta-cell tumor, 1 in 250,000

More than 90% are benign, they are a treatable cause of potentially fatal hypoglycemia.

The median age at presentation is 50 years, or usually presents in the third decade when it

is a component of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1

99% of insulinomas are within the pancreas and they are usually small (90% <2.0 cm).

20

Diagnosis

¾

Symptoms of hypoglycemia and +ve Whipple's triad

¾

Obtain measurements of plasma glucose, insulin, C-peptide, proinsulin and

-

hydroxybutyrate concentrations and to screen for circulating oral hypoglycemic

agents. a

High

levels of insulin, C-peptide, proinsulin inappropriate to a

low

plasma glucose in the absence circulating oral hypoglycemic agents.

¾

CT or MRI detects approximately 70–80% of insulinomas.

Treatment of insulinoma

Surgical resection of a solitary insulinoma is generally curative.

Diazoxide, which inhibits insulin secretion, or the somatostatin analogue octreotide can be

used to treat hypoglycemia in patients with unresectable tumors;

Urgent Treatment of hypoglycemia

Oral treatment with glucose tablets or glucose-containing fluids, candy, or food is

appropriate if the patient is able and willing to take these.

Parenteral therapy is necessary if he is unable or unwilling to take oral treatment because of

neuroglycopenia. Intravenous glucose

(Hypertonic glucose 25 g)

should be given, then

by a glucose infusion guided by serial plasma glucose measurements.

Subcutaneous or intramuscular glucagon (1.0 mg in adults) can be used, If intravenous

therapy is not practical, particularly in patients with T1DM. Because it acts by stimulating

glycogenolysis,

Glucagon is ineffective in glycogen-depleted individuals (e.g., alcohol-induced

hypoglycemia).

It also stimulates insulin secretion and is therefore less useful in T2DM.

These treatments raise plasma glucose concentrations only transiently, and patients should

therefore be urged to eat as soon as is practical to replete glycogen stores.