URINARY SYSTEM

Part 2

OBJECTIVES:

Cystic diseases of the kidney: including

o Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

o Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease

o Medullary cystic kidney disease

Listing the causes and pathogenetic factor of an important cause of

urinary outflow obstruction which is the nephrolithiasis and describing

features and complication of its important complication which is the

hydronephrosis.

Listing the pathological features of renal cell carcinoma and its variants.

Listing the pathological features of Wlim's tumor.

Listing and describing the pathological features of ureteric, vescical, and

urethral disorders including:

o Congenital abnormalities

o Inflammatory disorders

o tumors

CYSTIC DISEASES OF THE KIDNEY

These are a heterogeneous group comprising

a. hereditary b. developmental but nonhereditary c. acquired disorders.

They are important for several reasons:

1. They are practically common and often present diagnostic problems

2. Some are major causes of chronic renal failure (adult polycystic disease)

3. They can occasionally be confused clinically with malignant tumors.

4.

Simple Cysts: are a common but have no clinical significance. They can be multiple

or single, commonly up to 5 cm in diameter. They are translucent; filled with clear

fluid; lined by a single layer of cuboidal or flattened epithelium.

Dialysis-associated acquired cysts: occur with prolonged dialysis in those with end-

stage renal disease. They may bleed, causing hematuria. Occasionally, renal

adenomas or carcinomas arise in the walls of these cysts.

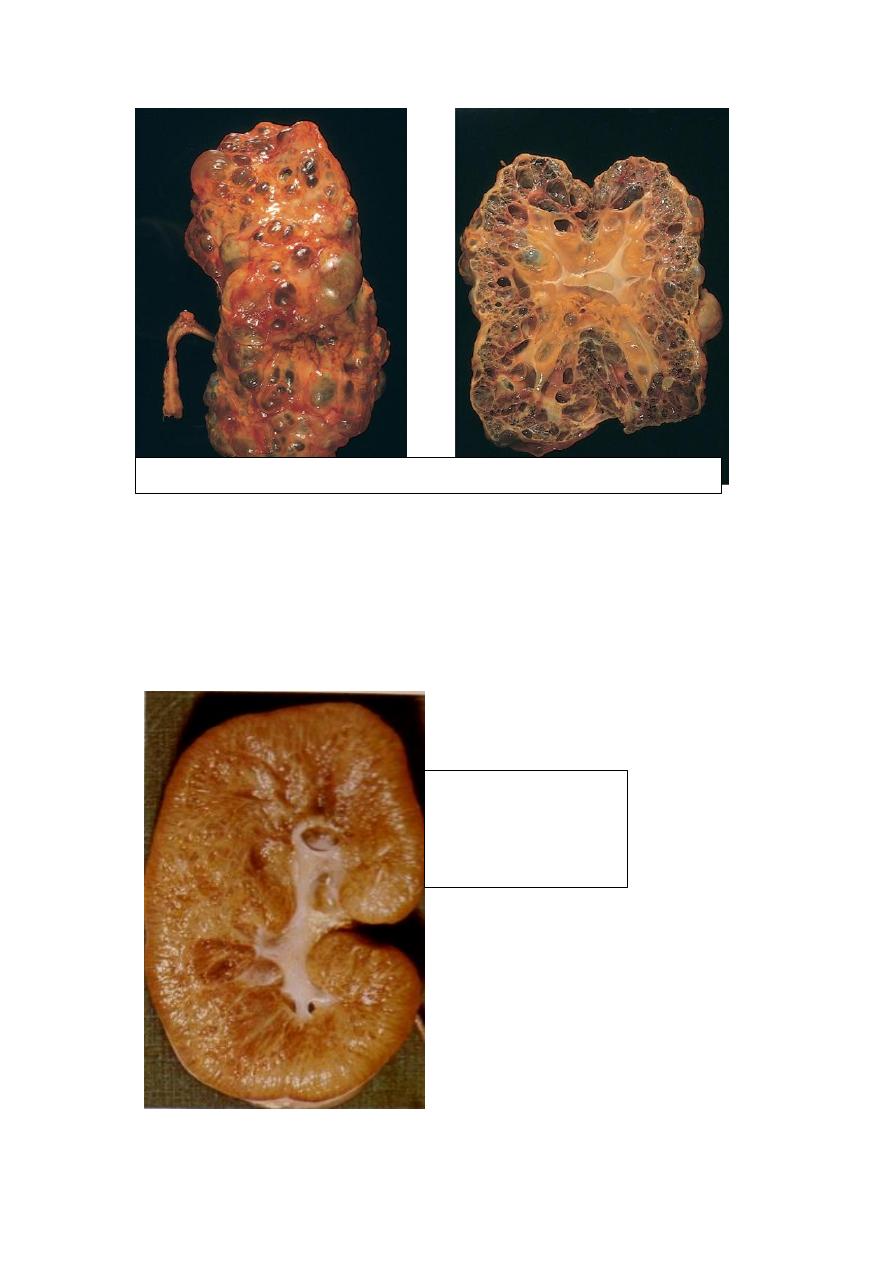

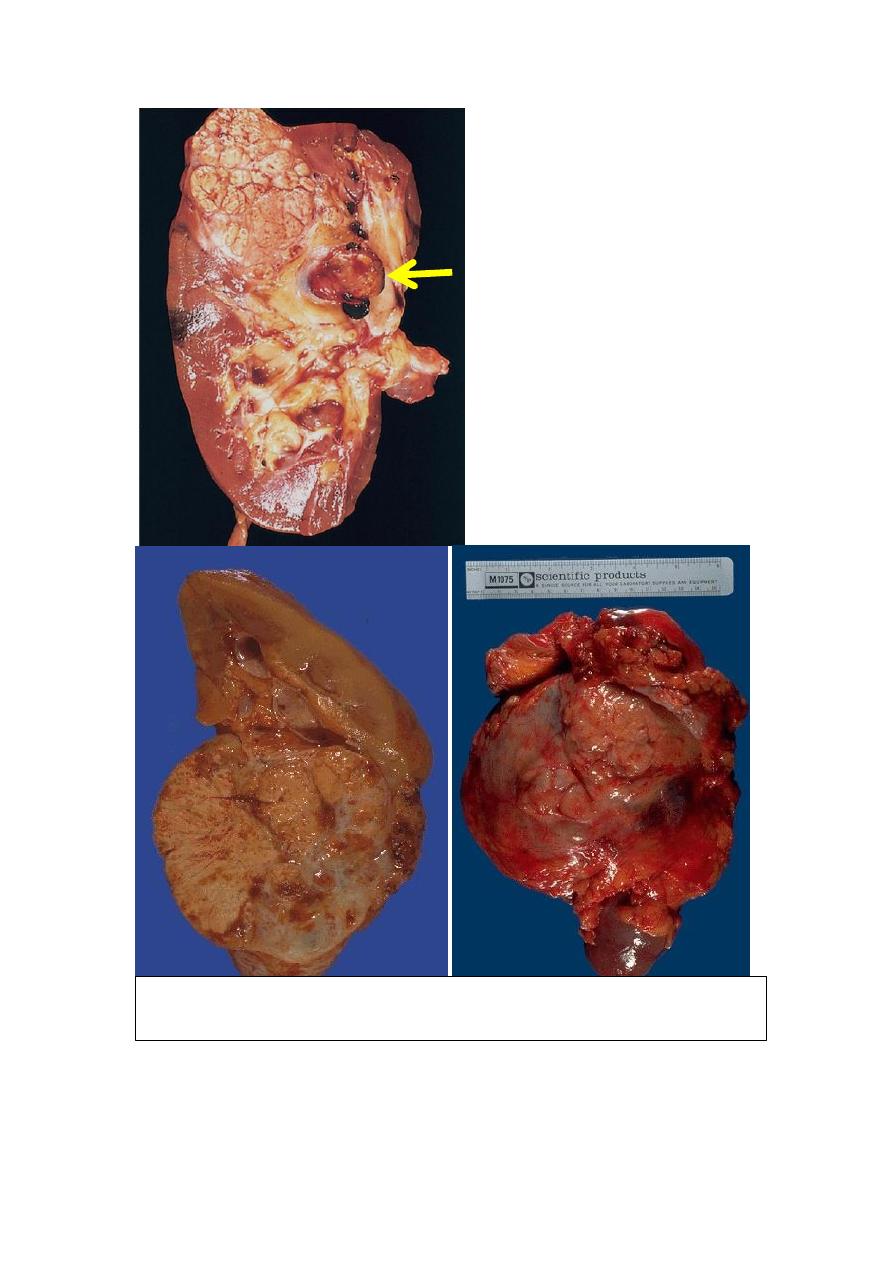

Autosomal Dominant (Adult) Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD): is

characterized by multiple expanding cysts of both kidneys that ultimately destroy the

intervening parenchyma. ADPKD is responsible for 10% of all chronic renal failures.

It is caused by inheritance of one of two autosomal dominant genes of very high

penetrance. The kidneys may be very large (up to 4 kg for each), and thus are readily

palpable abdominally. Grossly the kidney is composed of a mass of cysts of varying

sizes (up to 4 cm). The cysts are filled with fluid (clear, turbid, or hemorrhagic).

Microscopically, the cysts have often atrophic, lining. The pressure of the expanding

cysts leads to ischemic atrophy of the intervening renal substance.

Clinically: ADPKD in adults usually does not produce symptoms until the fourth

decade, by which time the kidneys are quite large. Intermittent gross hematuria

commonly occurs. The most important complications are hypertension and urinary

infection.

Saccular aneurysms of the circle of Willis are present in up to 30% of patients, and

these individuals have a high incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Asymptomatic

liver cysts occur in one-third of patients.

Autosomal Recessive (Childhood) Polycystic Kidney Disease (ARPKD) is a rare

developmental anomaly that is genetically distinct from ADPKD. Perinatal, neonatal,

infantile, and juvenile subcategories have been defined, depending on time of

presentation and the presence of associated hepatic lesions. Both kidneys are

invariably involved with numerous small cysts that give them a sponge-like

appearance. The cysts are lined by cuboidal cells. ARPKD is associated with multiple

epithelium-lined cysts in the liver. Young infants may die quickly from hepatic or

renal failure

.

Autosomal Dominant (Adult) Polycystic Kidney Disease

Autosomal Recessive

(Childhood) Polycystic

Kidney Disease

(ARPKD)

Medullary Cystic Disease (MCD)

This is of two major types of

1. Medullary sponge kidney a relatively common and usually harmless condition and

2. Nephronophthisis-medullary cystic disease complex, which is associated with renal

dysfunction (within 5-10 years). On the basis of the time of onset they are divided

into, infantile, juvenile (the most common), adolescent, and adult types.

Pathologic features of medullary cystic disease include small contracted kidneys with

numerous small typically at the cortico-medullary junction

URINARY OUTFLOW OBSTRUCTION

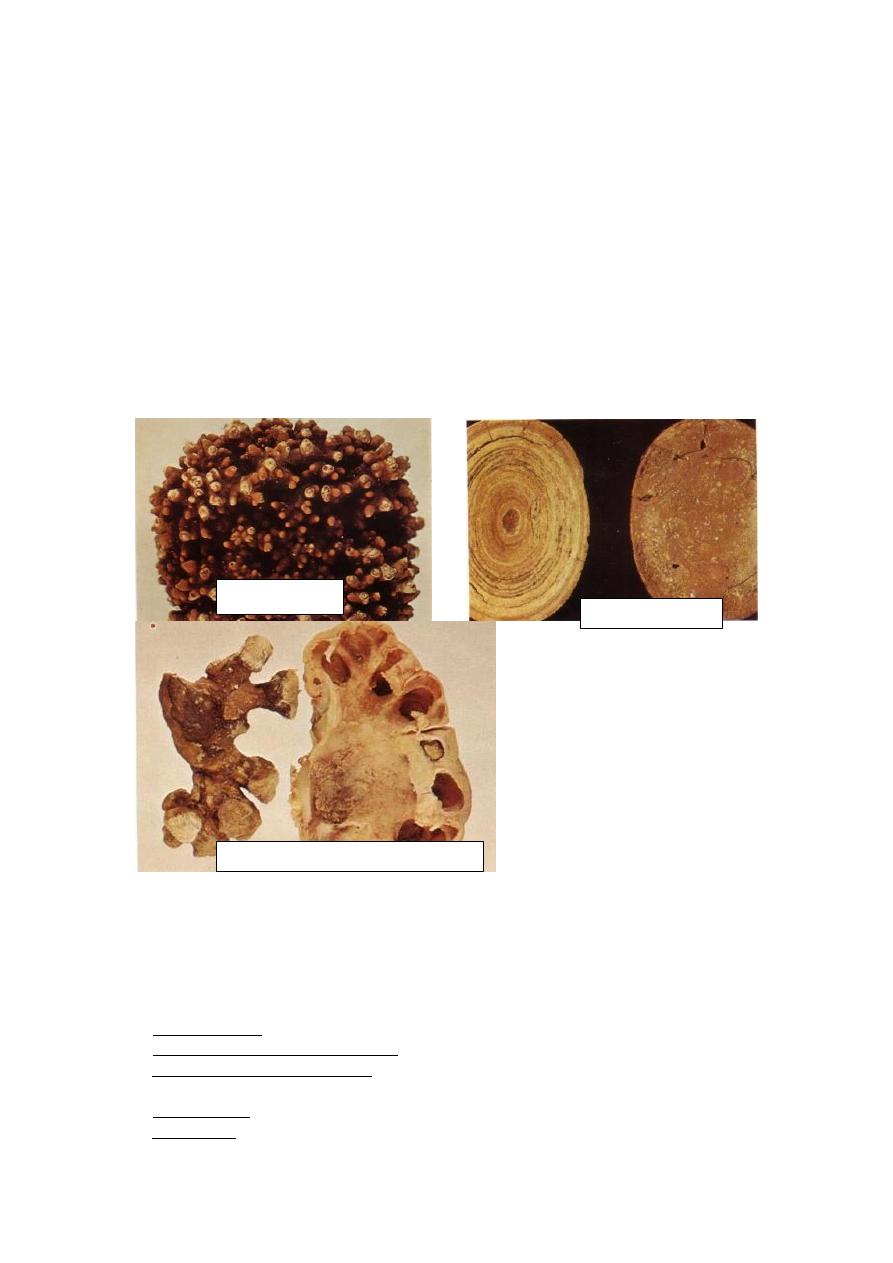

Renal Stones (Urolithiasis) these are frequent (1% of all autopsies) and mostly form

in the kidney. The majority (80%) are composed of either calcium oxalate or calcium

oxalate mixed with calcium phosphate; 10% are of magnesium ammonium phosphate,

and the remainder 10% are either uric acid or cystine stones. The most important

cause is increased urine concentration of the stone's constituents (supersaturation).

Those who develop calcium stones have

1. Hypercalciuria not associated with hypercalcemia due to either

a. Absorption of calcium from the gut in excessive amounts (i.e. absorptive

hypercalciuria)

b. Primary renal defect of calcium reabsorption (renal hypercalciuria).

Hypercalcemia is present in only 5% to 10% (due to hyperparathyroidism, vitamin D

intoxication, or sarcoidosis) and consequent hypercalciuria. In 20% of this subgroup,

there is excessive excretion of uric acid in the urine, which favors calcium stone

formation; the urates provide a nidus for calcium deposition. A high urine pH favors

crystallization of calcium phosphate and stone formation. Magnesium ammonium

phosphate stones almost always occur in persistently alkaline urine due to UTIs,

particularly with urea-splitting bacteria (as Proteus vulgaris and the Staphylococci).

Medullary

Cystic Disease

(MCD)

Gout and diseases involving rapid cell turnover (as the leukemias), lead to high uric

acid levels in the urine and uric acid stones. About half of the individuals with uric

acid stones, however, have no hyperuricemia but unexplained tendency to excrete

persistently acid urine (under pH 5.5), which favors uric acid stone formation (cf.

stones containing calcium phosphate).

Common sites of formation are renal pelvis and calyces as well as the bladder. Stone

may be small with smooth or jagged surface. Occasionally, progressive accumulation

of salts leads to the development of branching structures known as staghorn calculi,

which create a cast of the renal pelvis and calyceal system. These massive stones are

usually composed of magnesium ammonium phosphate; these do not produce

symptoms or significant renal damage. Smaller stones may pass into the ureter,

producing a typical intense pain known as renal colic. Often at this time there is gross

hematuria. The clinical significance of stones lies in their capacity to obstruct urine

flow or to produce sufficient trauma to cause ulceration and bleeding. In either case,

they predispose the sufferer to bacterial infection.

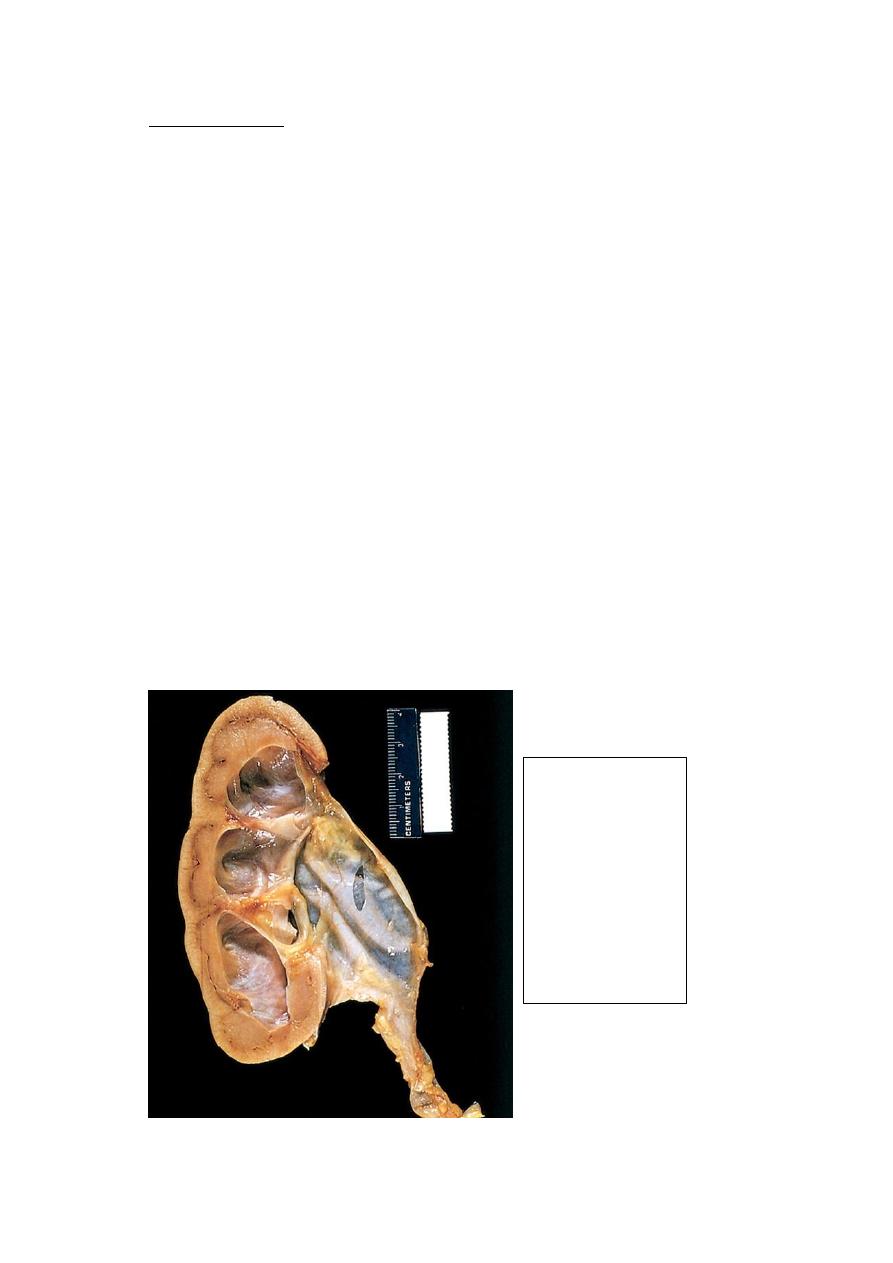

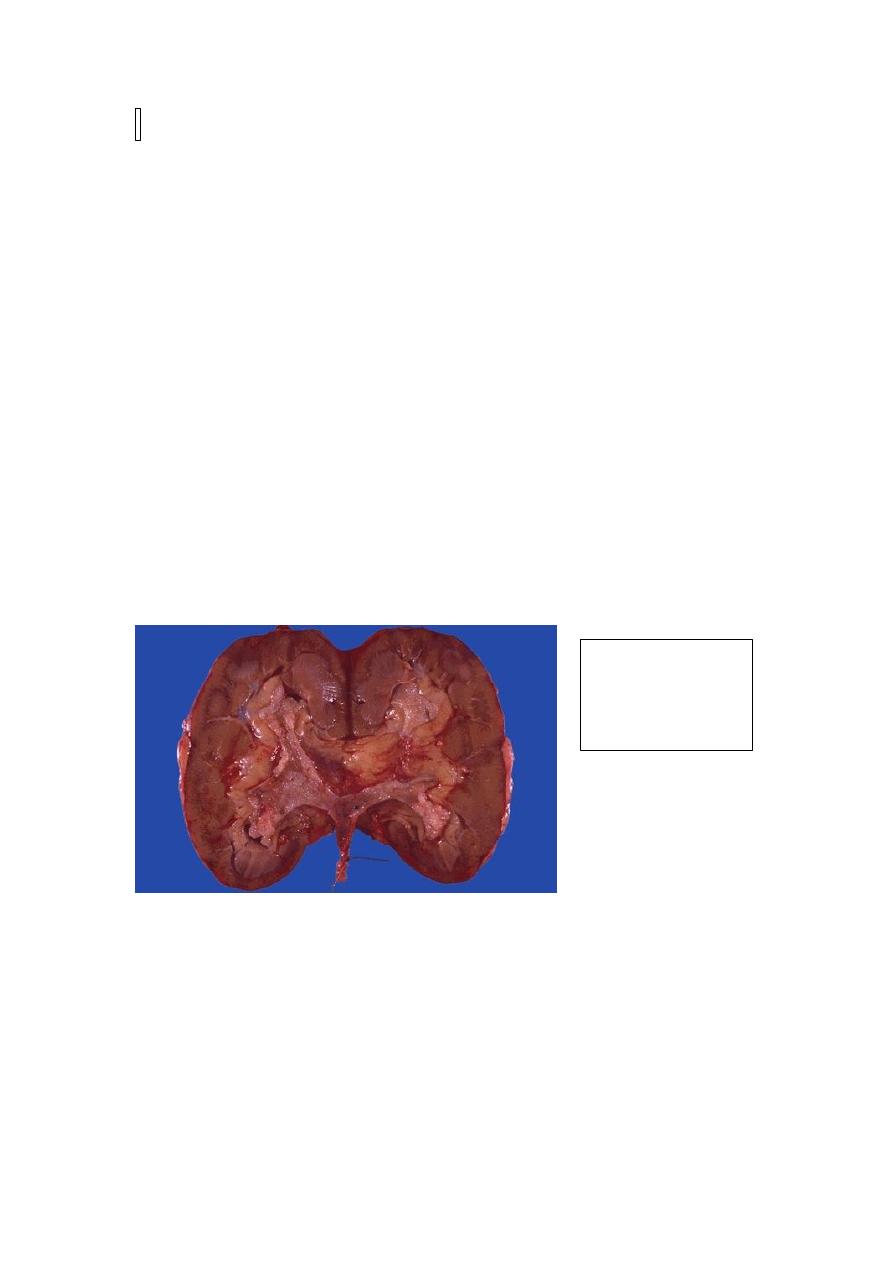

Hydronephrosis refers to dilation of the renal pelvis and calyces, with accompanying

atrophy of the renal parenchyma, caused by obstruction to the outflow of urine. The

obstruction may be sudden or insidious, and it may occur at any level of the urinary

tract, from the urethra to the renal pelvis. The most common causes are

1. Congenital: e.g. urethral atresia, ureteric or urethral valves, aberrant renal artery

2. Acquired:

a. Foreign bodies: calculi

b. Tumors of the prostate or bladder (benign or malignant)

c. Contiguous malignant disease: (retroperitoneal lymphoma, carcinoma of the cervix

or uterus)

d. Inflammation: prostatitis, ureteritis, urethritis

e. Neurogenic: Spinal cord damage with paralysis of the bladder

Oxalate stone

Uric acid stone

staghorn phosphate stone

f. Normal pregnancy: mild and reversible

Bilateral hydronephrosis occurs only when the obstruction is below the level of the

ureters. If blockage is at the ureters or above, the lesion is unilateral. Sometimes

obstruction is complete, allowing no urine to pass; usually it is only partial.

Pathogenesis

Even with complete obstruction, glomerular filtration persists for some time, and the

filtrate subsequently diffuses back into the lymphatic and venous systems. Because of

the continued filtration, the affected calyces and pelvis become dilated, often

markedly so. The unusually high pressure thus generated in the renal pelvis, as well as

that transmitted back through the collecting ducts, causes compression of the renal

blood vessels. Both arterial insufficiency and venous stasis result. The most severe

effects are seen in the papillae, because they are subjected to the greatest increases in

pressure. Accordingly, the initial functional disturbances are largely tubular,

manifested primarily by impaired concentrating ability. Thereafter the glomerular

filtration begins to diminish. Serious irreversible damage occurs in about 3 weeks

with complete obstruction, and in 3 months with incomplete obstruction.

Gross features

The changes vary with the degree and speed of obstruction

- With subtotal or intermittent obstruction, the kidney is massively enlarged

consisting almost entirely of the greatly distended pelvicalyceal system. The

renal parenchyma shows compression atrophy, with obliteration of the papillae

and flattening of the pyramids.

- With sudden complete obstruction, glomerular filtration is reduced relatively

early, and as a consequence, renal function may cease while dilation is still

slight.

Depending on the level of the obstruction, one or both ureters may also be dilated

(hydroureter).

Hydronephrosis:

There is marked

dilation of the

pelvi-calyceal

system and

thinning of renal

parenchyma.

Microscpic features

Early lesions show tubular dilation, followed by atrophy and fibrous replacement

with relative sparing of the glomeruli. Eventually, in severe cases the glomeruli also

become atrophic and disappear, converting the entire kidney into a thin shell of

fibrous tissue.

With sudden and complete obstruction, there may be coagulative necrosis of the

renal papillae.

Course & prognosis

Bilateral complete obstruction produces anuria. When the obstruction is below the

bladder, there is bladder distention. Incomplete bilateral obstruction causes polyuria

rather than oliguria, as a result of defects in tubular concentrating mechanisms.

Unilateral hydronephrosis may remain completely silent. Removal of obstruction

within a few weeks usually permits full return of function; however, with time the

changes become irreversible.

TUMORS

The kidney is the site of benign and malignant tumors. In general, benign tumors

(such as small cortical adenomas or medullary fibromas) have no clinical significance.

The most common malignant tumors of the kidney in descending order of frequency

are

1. Renal cell carcinoma

2. Nephroblastoma (Wilms tumor)

3. Transitional cell carcinoma of the calyces and pelvis

Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC)

This is derived from the renal tubular epithelium and represents the most common

primary malignant tumor of the kidney (80%). The mean age of incidence is 50 to 70

years. Risk factors include:

smoking,

hypertension,

obesity,

occupational exposure to cadmium,

and acquired polycystic disease complicating chronic dialysis (30-fold).

RCC are currently classified according to the molecular origins of these tumors. The

three most common forms are

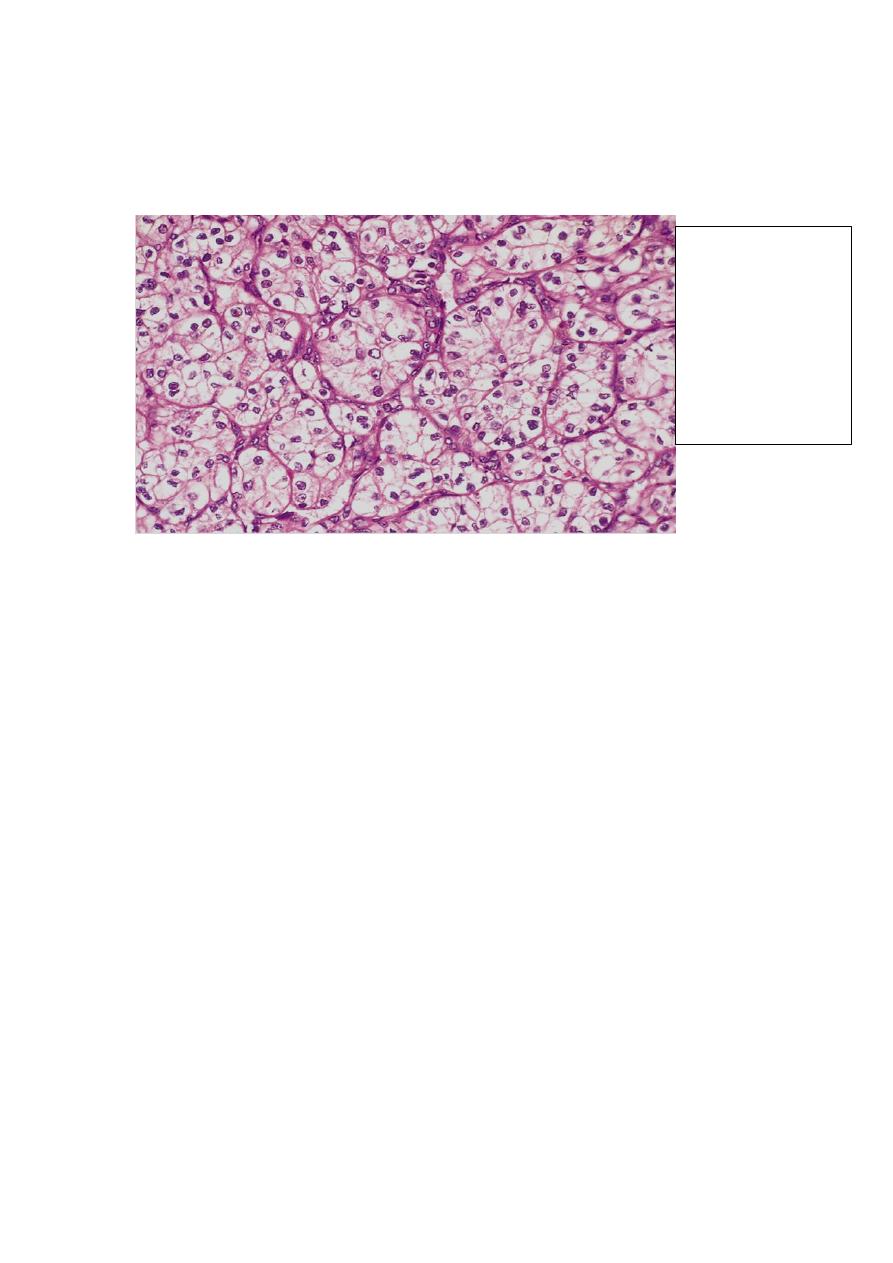

1. Clear Cell Carcinomas (80% of RCCs): these are made up of cells with clear or

granular cytoplasm. The majority are sporadic, but may occur in familial forms or in

association with von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHLD). The latter is autosomal

dominant and characterized by predisposition to a variety of neoplasms including

bilateral & often multiple RCC of clear cell type. Patients with VHLD inherit a germ-

line mutation of the VHL gene on chromosome 3 and lose the second allele by

somatic mutation. Thus, the loss of the normal copies of both these tumor suppressor

genes gives rise to clear cell carcinoma. It has been also confirmed that homozygous

loss of the VHL gene seems to be the common underlying molecular abnormality in

both sporadic and familial forms of clear cell carcinomas.

2. Papillary Renal Cell Carcinomas (10%). These tumors are frequently multifocal

and bilateral and like clear cell carcinomas, they occur in familial and sporadic forms.

The cause is the MET proto-oncogene. It is the increased dosage of the MET gene

(due to duplications of chromosome 7) seems to encourage neoplastic growth

abnormal growth in the proximal tubular epithelial cell precursors.

3. Chromophobe RCCs: these are the least common; they arise from intercalated cells

of collecting ducts. Their name indicates that the tumor cells stain more darkly than

cells in clear cell carcinomas. These tumors are unique in having multiple losses of

entire chromosomes, including chromosomes 1 and 2. In general, they have a good

prognosis.

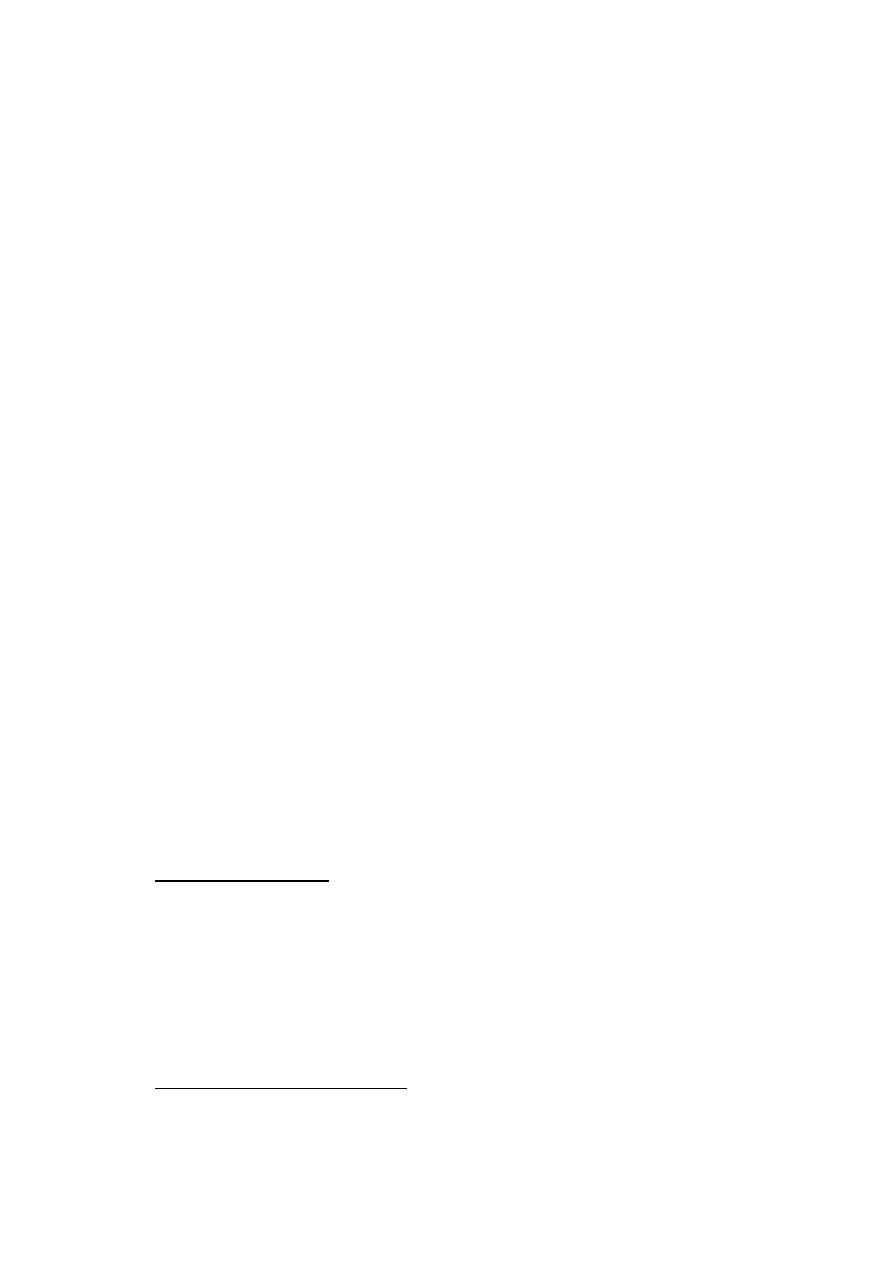

Pathologic features

Clear cell carcinoma

Gross features:

There is usually solitary spherical mass; large when symptomatic.

The cut surface is variegated; yellow-orange to gray-white with red areas of

hemorrhage. There are prominent areas of cystic degeneration.

Although the margins of the tumor are well defined, with enlargement extension

may occur in two directions

1. Into the pelvicalyceal system & as far down as the ureter.

2. Into the renal vein, then the inferior vena cava & even into the right side of

the heart.

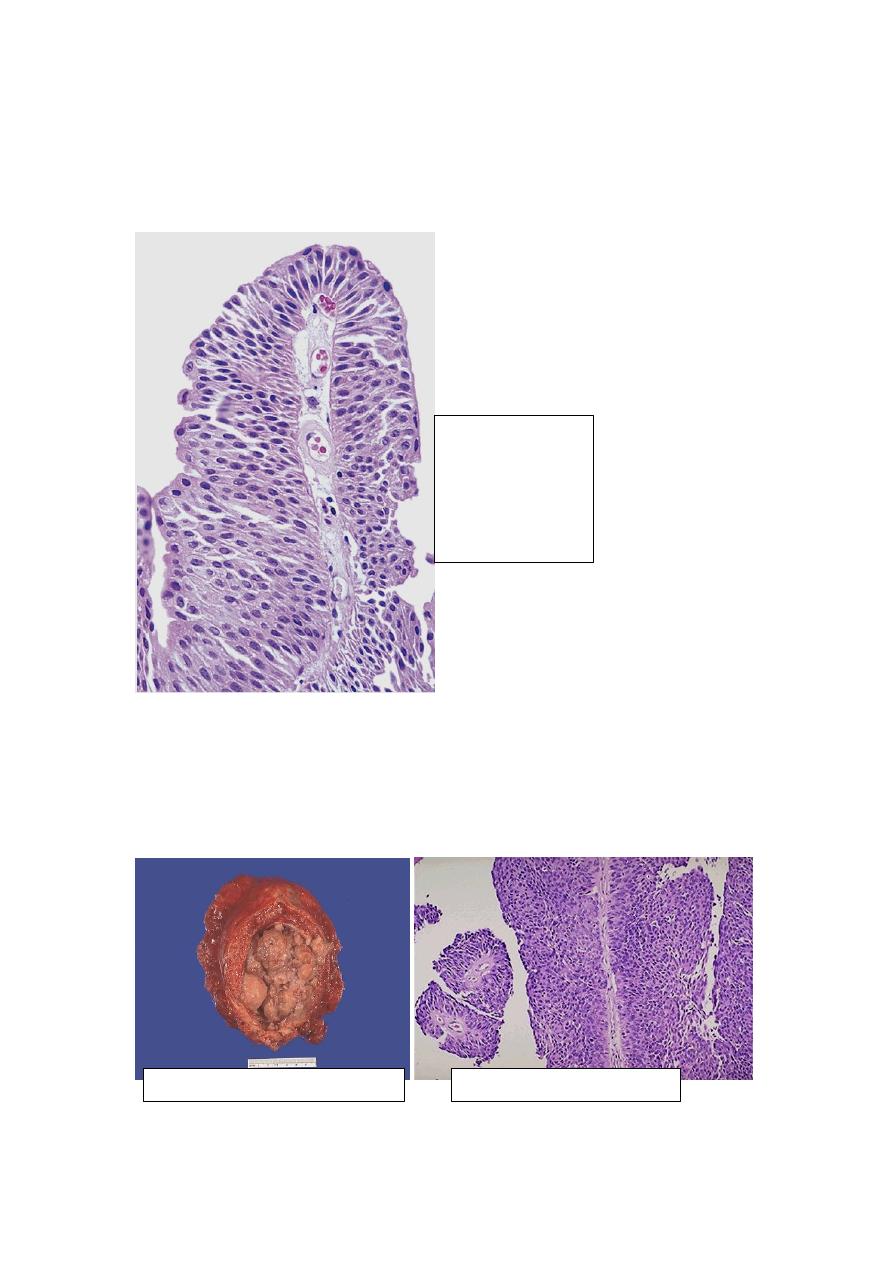

Microscopic features

The classic lipid- & glycogen-laden clear cells have well defined cell membranes.

The nuclei are usually small and round.

Typical cross-section of

yellowish, spherical neoplasm

in one pole of the kidney. Note

the tumor in the dilated,

thrombosed renal vein (arrow).

The varrigated appearance of RCC (yellowish-brownish with areas of

hemorrhage and necrosis

These cells are mixed to varying extent with cells having granular pink cytoplasm.

Some tumors exhibit marked degrees of anaplasia, with numerous mitotic figures

and markedly enlarged, hyperchromatic, pleomorphic nuclei (sarcomatoid RCC).

The stroma is usually scant but highly vascularized.

Papillary renal cell carcinomas

Exhibit papilla formation with fibrovascular cores.

They tend to be bilateral and multiple.

The cells can have clear or, more commonly, pink cytoplasm.

The classical triad of painless hematuria (the most frequent), a palpable abdominal

mass, and dull flank pain is characteristic. RCCs are well-known for their association

with several paraneoplastic syndromes. Polycythemia may occur; it results from

excessive secretion of erythropoietin by the tumor. Uncommonly, these tumors also

produce a variety of hormone-like substances, resulting in hypercalcemia,

hypertension, Cushing syndrome, etc. In many individuals the primary tumor remains

silent and is discovered only after its metastases have produced symptoms. Common

locations for metastases are the lungs and the bones. Forty percent of patients die of

the disease.

Wilms Tumor (WT) (nephroblastoma)

This is the most common primary renal tumor of children and the third most common

organ cancer in those younger than 10 years. WT may arise sporadically or be

familial. Some congenital malformations are associated with an increased risk of

developing Wilms' tumor such as aniridia, mental retardation, gonadal dysgenesis and

renal abnormalities. These conditions are associated with inactivation of the Wilms'

tumor 1 (WT1) gene, located on chromosome11. This gene is critical to normal renal

and gonadal development. Patients with the Beckwith syndrome (BWS);

characterized by enlargement of individual body organs (e.g., tongue, kidneys, or

liver) or hemihypertrophy of the entire body segments. In addition to Wilms' tumors,

patients with BWS are also at increased risk for developing other cancers e.g.

hepatoblastoma.

Well-defined nests

of the tumor cells

that appear clear

(lipid-laden) with

well defined cell

membranes. The

nuclei are usually

small and round

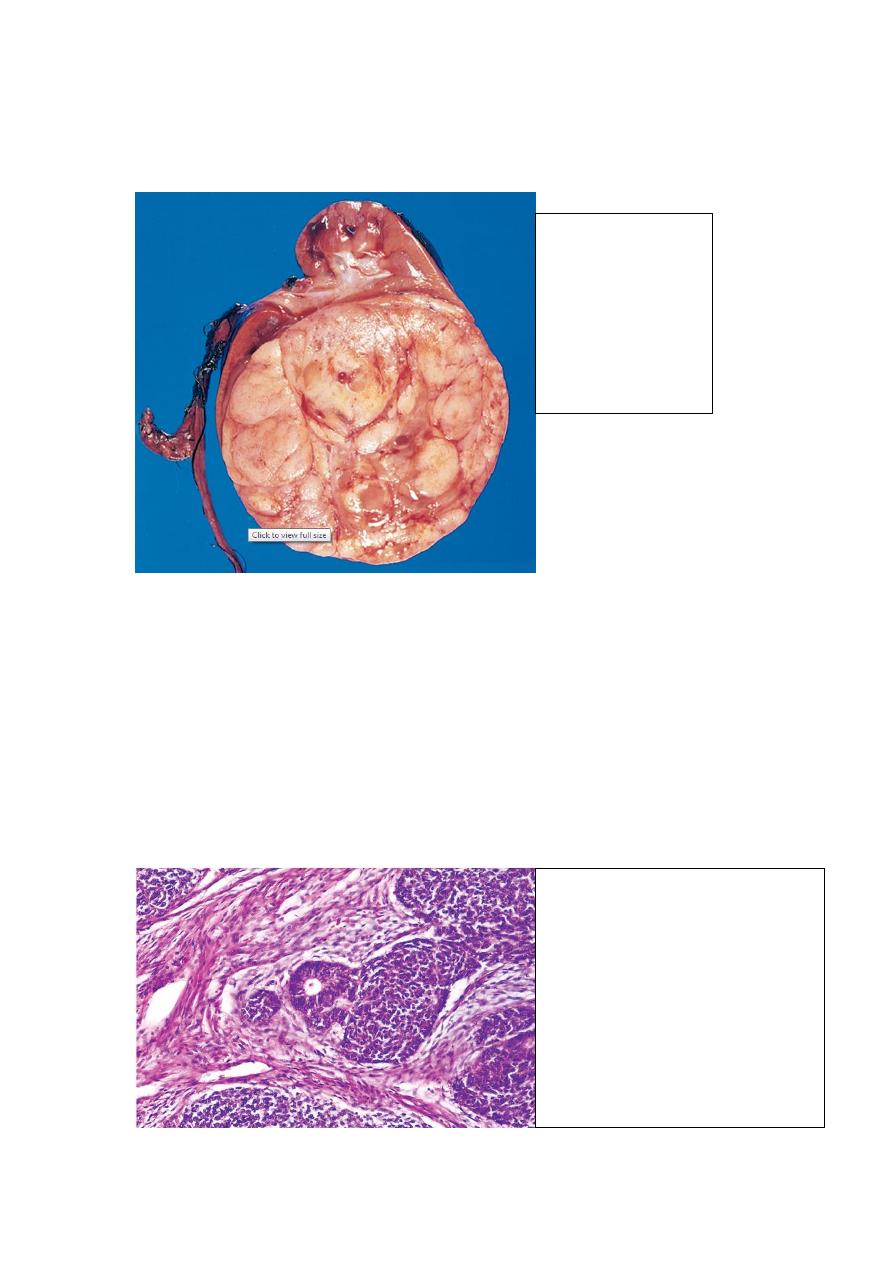

Gross features

WT tends to be large, well-circumscribed mass with soft, homogenous, tan to gray

cut section accentuated with occasional foci of hemorrhage, necrosis and cystic

degeneration.

Microscopic features

In WT there are attempts to recapitulate different stages of nephrogenesis.

WT contain a variety of tissue components, but all derived from the mesoderm.

The classic triphasic combination of blastemal, stromal, and epithelial cell types is

observed in most lesions.

- The blastemal component is represented by sheets of small blue cells

- The epithelial component (differentiation) is represented by abortive tubules

or glomeruli.

- The stromal component is represented usually by fibroblastic cells or

myxoid areas, although

skeletal

muscle

"differentiation"

and

other

mesenchymal elements may be seen.

The presence of anaplasia correlates with underlying p53 mutations, and the

emergence of resistance to chemotherapy.

Wilm's tumor:

The tumor is in the

lower pole of the

kidney with the

characteristic tan to

gray color and well-

circumscribed

margins.

Triphasic histology of Wilms'

tumor: the stromal component is

composed of spindle-shaped cells

in the less cellular area on the left;

the immature tubule in the center

is an example of the epithelial

component, and the tightly packed

blue cells the blastemal elements.

Clinically, there is a readily palpable abdominal mass, which may extend across the

midline and down into the pelvis. Fever and abdominal pain, with hematuria, are less

frequent. The prognosis of Wilms' tumor is generally very good, and excellent results

are obtained with a combination of nephrectomy and chemotherapy. WTs with diffuse

anaplasia, especially those with extra-renal spread, have the least favorable outcome.

RENAL PELVIS, URETER, URINARY BLADDER & URTHERA

URETERS

Congenital Anomalies these are rare, and mostly of little clinical significance.

However, some may contribute to urine outflow obstruction. Incompetent

ureterovesical junction predisposes to pyelonephritis. The majority of double ureters

are unilateral and of no clinical significance. A congenital ureteropelvic junction

obstruction is the most common cause of hydronephrosis in infants and children.

There is agenesis of the kidney on the opposite side in a significant number of cases

.

Diverticula are saccular outpouchings acting as pockets of stasis and secondary

infections. Hydroureter with elongation and tortuosity may be congenital leading to

hydronephrosis if untreated.

Ureteritis may be one component of UTI. With long-standing chronic ureteritis, there

may be aggregation of lymphocytes in the subepithelial region causing fine granular

mucosal surface (ureteritis follicularis), or the mucosa may become sprinkled with

tiny cysts (ureteritis cystica). Identical changes are found in the bladder. The two most

common tumors and tumor-like lesions

are fibroepithelial polyps and leiomyomas.

Primary malignant tumors are similar to those arising in the renal pelvis, calyces, and

bladder; the majority are transitional cell carcinomas. They cause obstruction and are

most frequently during the sixth and seventh decades. They can be multiple and may

occur concurrently with similar tumors in the bladder or renal pelvis.

Obstructive lesions of the ureters

A great variety of pathologic lesions may obstruct the ureters and give rise to

hydroureter, hydronephrosis, and sometimes pyelonephritis. The more important

causes include

1. impacted small stones

2. strictures (congenital or acquired),

3. primary carcinoma,

4. pregnancy,

5. retroperitoneal fibrosis & cancers of the rectum, bladder, prostate, ovaries, uterus

and cervix.

Sclerosing Retroperitoneal Fibrosis is a fibrous proliferative inflammatory process

encasing the retroperitoneal structures including the ureters and causing

hydronephrosis. Two thirds of the cases are idiopathic. The remaining cases are

attributed to drugs (ergot derivatives, β-adrenergic blockers), adjacent inflammatory

conditions or malignant disease. It may be associated with mediastinal fibrosis,

sclerosing cholangitis, and Riedel thyroiditis. This suggests that the disorder is

systemic in distribution but preferentially involves the retroperitoneum. An

autoimmune reaction, sometimes triggered by drugs, has been proposed.

URINARY BLADDER

Congenital anomalies

Diverticula are pouch-like evaginations of the bladder wall that may be congenital,

but more commonly acquired due to persistent urethral obstruction (e.g. prostatic

hyperplasia or neoplasia). In both forms, there are frequently multiple sac-like

pouches that range from less than 1 cm to 10 cm in diameter. Most diverticula are

small and asymptomatic, but may be sites of urinary stasis that predispose to infection

and the formation of bladder calculi.

Exstrophy is a developmental failure in the anterior wall of the abdomen and the

bladder, so that the bladder communicates directly through a large defect with the

surface of the body. The exposed bladder mucosa may undergo colonic glandular

metaplasia and is subjected to infections. There is an increased risk of carcinoma.

Vesicoureteral reflux is the most common and serious anomaly that contributes to

renal infection and scarring.

Congenital fistulas are abnormal connections between the bladder and the vagina,

rectum, or uterus.

Persistent urachus refers to failure of the urachus to close in part or in whole. When

it is totally patent, a fistulous urinary tract is created that connects the bladder with the

umbilicus. Sometimes, only the central region of the urachus persists, giving rise to

urachal cysts. Carcinomas, mostly adenocarcinomas, may arise in such cysts.

ACUTE & CHRONIC CYSTITIS

The common etiologic agents of bacterial cystitis are the E. coli, followed by Proteus,

&

Klebsiella. Women are more likely to develop cystitis due to their shorter urethras.

Bacterial pyelonephritis is frequently preceded by cystitis, with retrograde spread of

microorganisms into the kidneys and their collecting systems. Tuberculous cystitis is

almost always a consequence of renal tuberculosis. Fungal cystitis is usually due to

Candida albican. It is particularly seen in immunosuppressed patients or those

receiving long-term antibiotics. Schistosomal cystitis (Schistosoma haematobium) is

common in certain Middle Eastern countries, notably Egypt. Viruses (e.g.,

adenovirus), Chlamydia, and Mycoplasma may also be causes of cystitis.

Predisposing factors of cystitis include

1. Urinary obstruction e.g. prostatic hyperplasia, bladder calculi,tumors

2. cystocele or diverticula

3. Diabetes mellitus

4. Instrumentation

5. Immune deficiency.

Hemorrhagic cystitis sometimes complicates cytotoxic antitumor drugs (e.g.

cyclophosphamide). Radiation cystitis is due to radiation of the bladder region.

Most cases of cystitis take the form of nonspecific acute or chronic inflammation of

the bladder. Gross features

There is hyperemia of the mucosa.

Hemorrhagic cystitis shows in addition a hemorrhagic component; this form is

sometimes follows radiation injury, antitumor chemotherapy, or adenovirus infection.

Suppurative cystitis is characterized by the accumulation of large amounts of

suppurative exudate.

Ulcerative cystitis refers to cystitis associated with ulceration of large areas of the

mucosa, or sometimes the entire bladder mucosa.

Persistence of the infection leads to chronic cystitis, which shows red, friable,

granular, sometimes ulcerated mucosa. Chronicity is also associated with fibrous

thickening and inelasticity of the bladder wall.

Microscopic features

In acute cystitis there are the expected features of acute inflammation.

In chronic forms there is chronic inflammatory cells infiltration with fibrosis.

Variants of chronic cystitis include Follicular cystitis and Eosinophilic cystitis

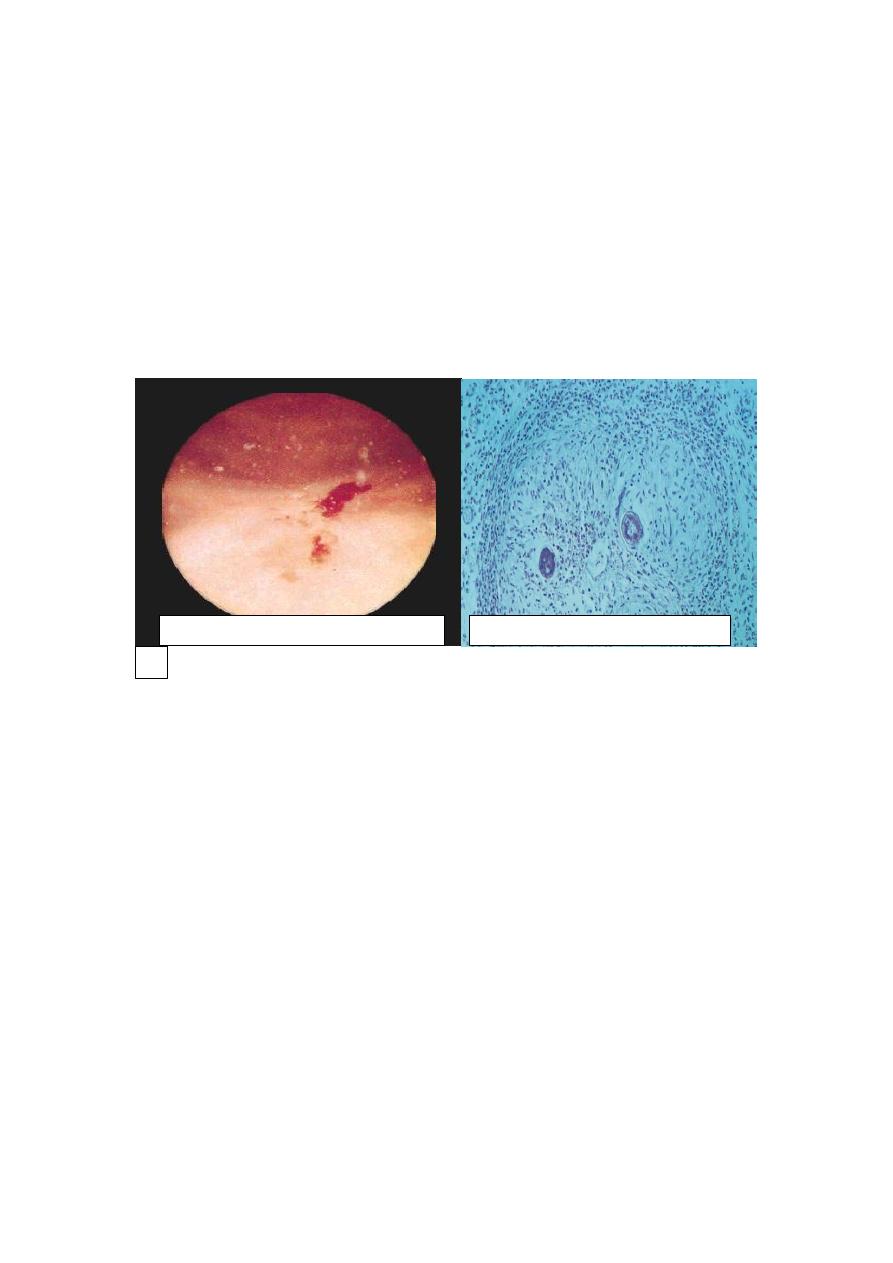

Schistomal cystitis: urogenital bilharziasis is caused by S. haematobium. Eggs are

deposited in the superior rectal vein. From there, they pass through anastomoses into

the veins of the wall of urinary bladder. There they cause granulomatous cystitis with

eosinophilic infiltrate & fibrosis. These granulomas are visible under endoscopy as

minute granules referred to as “sand grain” cystitis. The eggs eventually die in the

tissue with regressive calcification.The condition may be complicated by

a. Extensive fibrosis that may impinge on the ureteric orifices with eventual

hydronephrosis

b. Carcinoma of bladder that is frequently squamous in type; as this form of cystitis

can be associated with squamous metaplasia of the native transitional epithelium.

Special Forms of Cystitis

These are distinctive by either their morphologic appearance or their causation.

1. Interstitial Cystitis (Hunner Ulcer): a painful form of chronic cystitis occurring

most frequently in women. Cystoscopy shows fissures and punctate hemorrhages in

the mucosa, sometimes with chronic mucosal ulcers (Hunner ulcers). Infiltration by

mast cells is characteristic of this disease. The condition may be of autoimmune

origin.

2. Malakoplakia is characterized macroscopically by soft, yellow, slightly raised

mucosal plaques 3 to 4 cm in diameter and histologically by infiltration with large,

foamy macrophages with debris of bacterial origin (mostly E. coli) (Fig. 21-27). In

addition, laminated mineralized concretions (Michaelis-Gutmann bodies) are typically

present. Similar lesions have been described in other organs e.g. colon, lungs, bones.

It occurs with increased frequency in immuno-suppressed transplant recipients and as

a result of defects in phagocytic or degradative function of macrophages.

3. Polypoid Cystitis is an inflammatory condition resulting from irritation to the

bladder mucosa mostly by indwelling catheters. The urothelium is thrown into broad,

bulbous, polypoid projections as a result of marked submucosal edema.

METAPLASTIC LESIONS

Cystitis Glandularis and Cystitis Cystica: these terms refer to common lesions in

which nests of transitional epithelium (Brunn nests) grow downward into the lamina

propria and undergo transformation of their central epithelial cells into columnar

epithelium lining (cystitis glandularis) or cystic spaces lined by urothelium (cystitis

Bilharzial (“sand grain”) cystitis

Schistosomic granuloma (HE)

x 150

cystica). The two processes often coexist. In a variant of cystitis glandularis, goblet

cells are present (intestinal metaplasia).

Both variants are common microscopic incidental findings in relatively normal

bladders and are not associated with an increased risk of adenocarcinoma.

Two forms of metaplasia occur in response to injury

1. Squamous Metaplasia

2. Nephrogenic Metaplasia (Nephrogenic Adenoma): the urothelium may be focally

replaced by cuboidal epithelium, which can assume a papillary growth pattern with

subjacent tubular proliferation.

TUMORS OF THE URINARY BLADDER AND COLLECTING SYSTEM

(Renal Calyces, Renal Pelvis, Ureter, and Urethra)

The entire urinary collecting system from renal pelvis to urethra is lined with

transitional epithelium, so its epithelial tumors assume similar morphologic patterns.

Tumors in the collecting system above the bladder are relatively uncommon; those in

the bladder, however, are a more frequent cause of death than are kidney tumors.

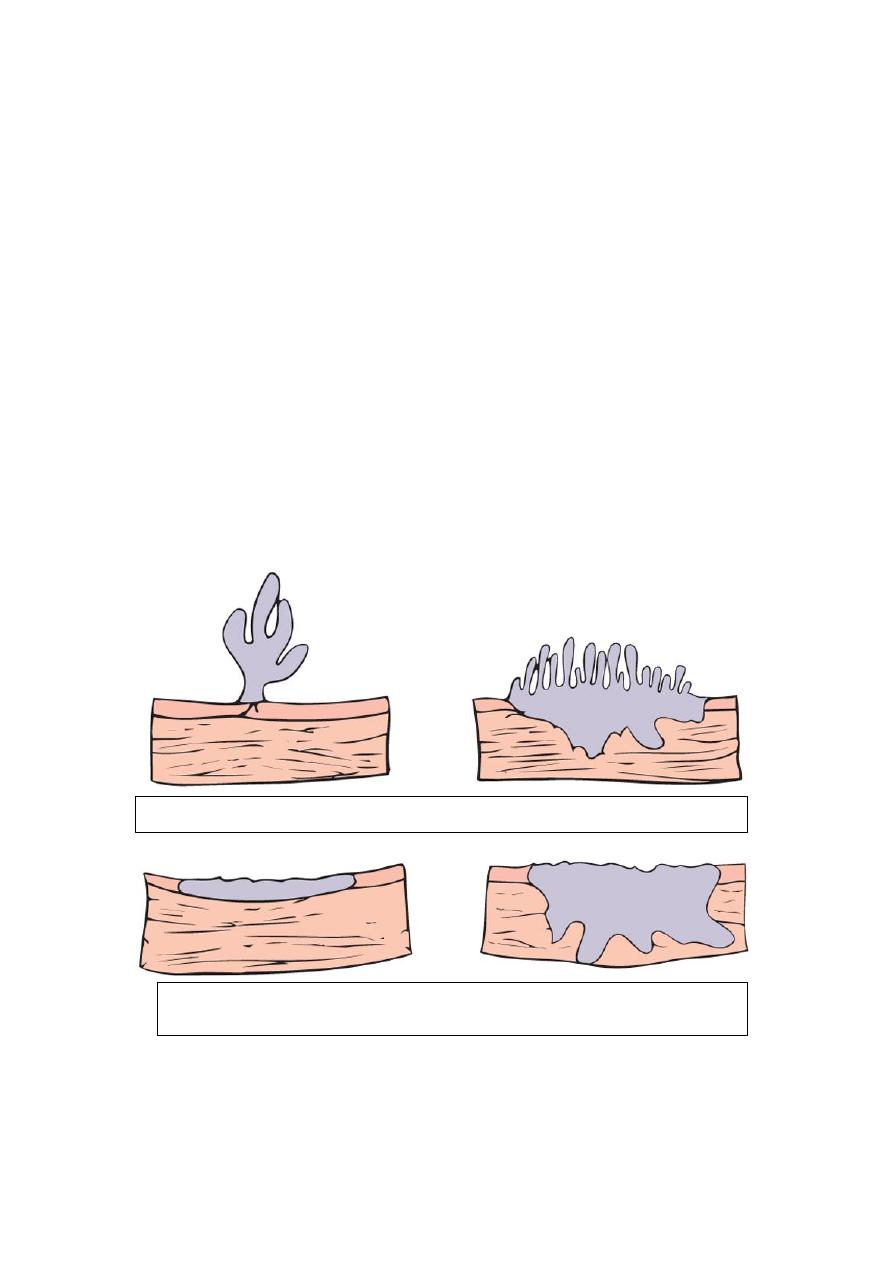

Gross features

Four morphologic patterns are recognized that range from small benign papillomas to

large invasive cancers. These tumors are classified into

1. Benign papilloma (rare)

2. Papillary urothelial neoplasms of low malignant potential, and

3. Urothelial carcinoma (low and high grade)

Papillomas are very rare, small (up to 1 cm) benign tumors with frondlike structures

having a delicate fibrovascular core covered by multilayered, well-differentiated

Papilloma-papillary carcinoma

Invasive papillary

carcinoma

Flat non-invasive carcinoma

Flat invasive carcinoma

transitional epithelium. Such lesions are usually solitary. They rarely recur once

removed.

Urothelial (transitional) cell carcinomas range from papillary to flat, noninvasive to

invasive and low grade to high grade.

Low-grade carcinomas are always papillary and are rarely invasive, but they may

recur after removal.

High-grade carcinoma can be papillary or occasionally flat; they may cover larger

areas of the mucosal surface, invade deeper, and have a shaggier necrotic surface than

do low-grade tumors. Occasionally, these cancers show foci of squamous cell

differentiation, but only 5% of bladder cancers are true squamous cell carcinomas.

Carcinomas of grades II and III infiltrate surrounding structures, spread to regional

nodes, and, on occasion, metastasize widely.

Low-grade

papillary

urothelial

carcinoma of the

bladder

Exophytic TCC of urinary

bladder

High grade Papillary TCC

Painless hematuria is the dominant clinical presentation of all these tumors. They

affect men three times more frequently than women and usually develop between

the ages of 50 and 70 years.

Risk factors of bladder cancer are

1. Exposure to β-naphthylamine (50 times increased risk).

2. Cigarette smoking

3. Chronic cystitis

4. schistosomiasis of the bladder

5. Certain drugs (cyclophosphamide).

A wide variety of genetic abnormalities are seen in bladder cancers; of these,

mutations involving several genes on chromosome 9, p53, and FGFR3 are the most

common.

The prognosis of bladder tumors depends on their histologic grade and the depth of

invasion of the lesion; the latter is much more important. Except for benign

papillomas, all tend to recur after removal. Lesions that invade the ureteral or urethral

orifices cause urinary tract obstruction. Overall 5-year survival is 57%. With deep

penetration of the bladder wall the 5-year survival rate is less than 20%.

Papillary tumors occur much less frequently in the renal pelvis than in the bladder,

they nonetheless make up to 10% of primary renal tumors. Patients present with

painless hematuria, and may develop hydronephrosis. Infiltration of the walls of the

pelvis, calyces, and renal vein worsens the prognosis. Despite removal of the tumor

by nephrectomy, fewer than 50% of patients survive for 5 years.

Cancer of the ureter is fortunately the rarest of the tumors of the collecting system.

The 5-year survival rate is less than 10%.

Papillary TCC of

renal pelvis