CHAPTER NINE

PATHOLOGY OF THE MALE GENITAL SYSTEM

Objectives:

Describe the penile neoplasm.

Identify the histological features of testicular atrophy associated with infertility cases.

Identify the gross appearance of hydrocele and torsion of testis.

Describe the classification and the histogenesis of Testicular tumors.

Identify the gross and histological features of: - Benign prostatic hyperplasia. - Carcinoma of the

prostate.

Malformations of the Penis

Hypospadias is the most common malformation (1 in 250 live male births). It refers to the abnormal location of

the distal urethral orifice along the ventral aspect of the penis. The urethral orifice is sometimes constricted,

resulting in urinary tract obstruction.

Epispadias: the urethral orifice is situated on the dorsal aspect of the penis. Like hypospadias, epispadias may

produce lower urinary tract obstruction or incontinence.

Inflammatory Lesions of the penis

Balanitis refer to local inflammation of the glans penis; it may be associated with inflammation of the overlying

prepuce. Most cases occur due to poor local hygiene in uncircumcised males, with accumulations of smegma

(desquamated epithelial cells, sweat, and debris) that acts as a local irritant. The distal penis is typically red,

swollen, and tender; a purulent discharge may be present.

Phimosis refers to the difficulty of retracting the prepuce over the glans. It may be congenital but most cases

are acquired from scarring of the prepuce secondary to previous balanitis.

Genital candidiasis is particularly common in patients with diabetes mellitus. Candidiasis presents as a

painful, intensely pruritic erosions involving the glans penis, scrotum, and adjacent intertriginous areas.

Scrapings or biopsy specimens of the lesions reveal characteristic budding yeast forms & pseudohyphae within

the superficial epidermis.

Penile Neoplasms

Squamous cell carcinomas of the penis are relatively uncommon. Most cases occur in uncircumcised patients

older than 40 years of age. Etiological factors include poor hygiene that expose the area to potential carcinogens

in smegma, smoking, and infection with human papillomavirus (HPV), particularly types 16 and 18. These

carcinomas are generally preceded by dysplastic changes termed intraepithelial neoplasia that may culminate in

carcinoma in situ. Clinical variants of carcinoma in situ, all strongly associated with HPV infection, occur on

the penis

1. Bowen disease (Erythroplasia of Queyrat) a solitary, erythematous, plaque-like lesion on the shaft of the

penis that displays microscopically malignant cells throughout the epidermis. It may progress to invasive

carcinoma in one third of the cases.

2. Bowenoid papulosis presents as multiple reddish brown papules on the shaft, glans or scrotum; it is and most

often transient, with only rare progression to carcinoma.

Gross features of invasive Squamous cell carcinoma

This tumor appears as a gray, crusted, papular lesion, most commonly on the glans penis or prepuce.

In many cases, the carcinoma infiltrates the underlying connective tissue to produce an indurated, ulcerated

lesion with irregular margins

Microscopic features

SCC is usually a keratinizing with infiltrating margins.

Verrucous carcinoma is very well differentiated variant of squamous cell carcinoma characterized by a

papillary architecture & rounded, pushing margins.

Most cases of squamous cell carcinoma of the penis are indolent. Regional metastases are present in the

inguinal lymph nodes in approximately 25% of patients at the time of diagnosis. Distant metastases are

relatively uncommon. The overall 5-year survival rate averages 70%.

SCROTUM

The skin of the scrotum may be affected by several inflammatory conditions, including local fungal infections

and systemic dermatoses.

Squamous cell carcinoma, the most common of the generally rare scrotal tumors, but represents the first

observed human malignancy associated with environmental influences i.e. a high incidence in chimney sweeps.

Hydrocele is an accumulation of serous fluid within the tunica vaginalis & represents the most common cause

of scrotal enlargement. It may arise in response to neighboring infections or tumors, or it may be idiopathic.

Hematoceles & chyloceles, represent accumulations of blood or lymphatic fluid within the tunica vaginalis

respectively. In extreme cases of lymphatic obstruction, caused, for example, by filariasis, the scrotum and the

lower extremities may enlarge to dreadful proportions, a condition termed elephantiasis.

Cryptorchidism

This refers to failure of testicular descent into the scrotum leading to malposition of the gonad anywhere along

its migration pathway. Normally, the testes descend from the coelomic cavity into the pelvis and then through

the inguinal canals into the scrotum during intrauterine life. The diagnosis of cryptorchidism is difficult before 1

year of age, because complete testicular descent into the scrotum is not invariably present at birth. By 1 year of

age, cryptorchidism is present in 1% of the males and in 10% of these cases is bilateral. Several influences may

interfere with testicular descent including

1. Hormonal abnormalities

2. Intrinsic testicular abnormalities

3. Obstruction of the inguinal canal

4. Congenital syndromes.

In the vast majority of cases, however, the cause is unknown.

Complications of cryptorchidism include

1. Sterility in bilateral cases.

2. Atrophy of the cryptorchid testis and even of the contralateral descended gonad.

3. Malignancy of the cryptorchid testis (up to 5 times increased risk). An increased risk is also noted in the

contralateral, normally descended testis, suggesting that some intrinsic abnormality, rather than simple failure of

descent, may be responsible for the increased cancer risk.

Surgical placement of the undescended testis into the scrotum (orchiopexy) before puberty decreases the

likelihood of testicular atrophy and reduces, but does not eliminate, the risk of cancer and infertility. The

cryptorchid testis may be of normal size early in life, although some degree of atrophy is usually present by the

time of puberty with microscopic evidence of tubular atrophy, fibrosis & hyalinization. Loss of tubules is

usually accompanied by hyperplasia of Leydig cells. Foci of intratubular germ cell neoplasia may be present in

cryptorchid testes and may be the source of subsequent cancers developing in these organs.

Other causes of testicular atrophy (apart from cryptorchidism) include

1. Chronic ischemia

2. Trauma

3. Radiation

4. Antineoplastic chemotherapy

5. Conditions associated with elevation in estrogen levels (e.g., cirrhosis)

Inflammatory Lesions of the testis & epididymis

Inflammatory lesions are more common in the epididymis than in the testis. Causes include venereal diseases,

nonspecific epididymitis and orchitis, mumps, and tuberculosis.

Nonspecific epididymitis and orchitis usually begin as a primary UTI with subsequent climbing infection of the

testis through the vas deferens or lymphatics of the spermatic cord. The involved testis is typically swollen and

tender and contains a predominantly neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate.

Orchitis complicates mumps infection in roughly 20% of infected adult males but rarely occurs in children.

The affected testis is edematous and congested and contains a predominantly lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory

infiltrate. There may be an associated considerable loss of seminiferous epithelium with resultant tubular

atrophy, fibrosis, and sterility.

Granulomatous orchitis may be due to infections and autoimmune injury. Of these, tuberculosis is the most

common. Testicular tuberculosis generally begins as an epididymitis, with secondary involvement of the testis.

The histologic changes include granulomatous inflammation and caseous necrosis, identical to that seen in

active tuberculosis in other sites.

TESTICULAR NEOPLASMS

Testicular neoplasms are the most important cause of firm, painless enlargement of the testis. The peak

incidence is between the ages of 20 and 34 years. In adults, 95% of testicular tumors arise from germ cells, and

all are malignant. Neoplasms derived from Sertoli or Leydig cells (sex cord/stromal tumors) are uncommon

and, in contrast to tumors of germ cell origin, usually pursue a benign clinical course.

The etiology of testicular neoplasms is not known.

The following are risk factors

1. Cryptorchidism: a history of this condition is present in 10% of testicular cancer.

2. Intersex syndromes, including androgen insensitivity syndrome and gonadal dysgenesis.

3. Genetic & ethnic influences as manifested by

a. Family history: the risk of neoplasia is increased in siblings of males with testicular cancers.

b. Cancer in one testis is associated with a markedly increased risk in the contralateral testis.

A wide range of abnormalities in testicular germ cell neoplasms have been detected, the most common of which

is an isochromosome of the short arm of chromosome 12. However, the role of such aberrations remains

unclear.

c. Whites are affected more commonly than blacks.

Classification and Histogenesis of Testicular tumors

The WHO classification is the most widely used. In this, germ cell tumors of the testis are divided into two

broad categories, based on whether they contain

1. A single histologic pattern (60% of cases) or

2. Multiple histologic patterns (40% of cases).

Germ cell tumors of the testis arise from primitive cells that may either differentiate along gonadal lines to

produce seminomas or transform into a totipotential cell population, giving rise to nonseminomatous germ cell

tumors. Such totipotential cells may remain largely undifferentiated to form embryonal carcinomas, may

differentiate along extra-embryonic lines to form yolk sac tumors & choriocarcinomas, or may differentiate

along somatic cell lines to produce teratomas. This proposed histogenesis is supported by the high frequency of

mixed histologic patterns among nonseminomatous germ cell tumors.

Most testicular tumors arise from in situ lesions designated intratubular germ cell neoplasia. Such in situ

lesions are seen in adjacent to a testicular germ cell tumor in virtually all cases.

Seminomas

This is the most common testicular germ cell neoplasm, accounting for 50% of these tumors. The peak

incidence is between 34 to 45 years, which is about 1 decade later than that of most other GCTs. Before

puberty, seminoma is extremely rare; in fact, it does not occur in the first decade of life especially in children

younger than 5 years. Most patients present with a typically painless testicular enlargement.

Gross features

They are soft, well-demarcated, usually homogeneous, gray-white or pale tumors that bulge from the cut

surface of the affected testis

The neoplasms are typically confined to the testis.

Large tumors may contain foci of coagulation necrosis, usually without hemorrhage.

Microscopically

Seminomas are composed of large, uniform cells with distinct cell borders, clear, glycogen-rich cytoplasm,

and round nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli

The cells are often disposed in small lobules with intervening fibrous septa.

A lymphocytic infiltrate is usually present.

A granulomatous inflammatory reaction may also be present.

In as many as 25% of cases, cells staining positively for human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) can be seen.

Some of these hCG-expressing cells are morphologically similar to syncytiotrophoblasts, and they are

presumably the source of the elevated serum hCG concentrations that may be encountered in some males

with pure seminoma.

Spermatocytic seminoma: is a much less common morphologic variant of seminoma that tend to occur in

older patients. It contains cells with round nuclei with spiral deposition of chromatin that are reminiscent of

secondary spermatocytes. The cytoplasm of tumor cells is eosinophilic and does not contain glycogen .A high

mitotic activity is often present. It typically occurs in men older than 50 years of age (median, 55 years)

Embryonal carcinoma occurs most frequently between 25 and 35 years of age, which is 10 years earlier than

the age range for seminoma. It is rare after the age of 50 years and does not occur in infancy. Most patients

present with a painless unilateral enlarging testicular mass. Approximately two thirds of cases have

retroperitoneal lymph node or distant metastases at the time of diagnosis.

Gross features

Is an ill-defined, invasive tumor that contains foci of hemorrhage and necrosis.

The primary lesions may be small, even in patients with systemic metastases.

Larger lesions may invade the epididymis and spermatic cord.

Microscopic features.

The constituent cells are large and primitive (undifferentiated) looking, with basophilic cytoplasm, indistinct

cell borders, and large nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Mitoses are frequent including abnormal ones

The neoplastic cells are disposed in solid sheets that may contain glandular structures and irregular papillae

In most cases, other germ cell tumors (e.g., yolk sac tumor, teratoma, choriocarcinoma) are admixed with the

embryonal carcinoma. In fact, pure embryonal carcinomas are quite rare.

Yolk sac tumors (YST) (endodermal sinus tumors)

These are the most common primary testicular neoplasm in children younger than 3 years of age. In adults, yolk

sac tumors are most often seen admixed with embryonal carcinoma. Yolk sac tumors represent endodermal

sinus differentiation of totipotential neoplastic cells.

Grossly, these tumors are often large and may be well demarcated.

Microscopy discloses low cuboidal to columnar epithelial cells forming microcysts, sheets, glands, and papillae,

often associated with eosinophilic hyaline globules. A distinctive feature is the presence of structures

resembling primitive glomeruli, the so-called Schiller-Duvall bodies. α-fetoprotein (AFP) can be demonstrated

within the cytoplasm of the neoplastic cells by immunohistochemical techniques.

Choriocarcinomas represent differentiation of pluripotent neoplastic germ cells along trophoblastic lines.

Grossly, they are often small, nonpalpable lesions, even with extensive systemic metastases. Microscopically,

they are composed of sheets of small cuboidal cells intermingled with large, eosinophilic syncytial cells

containing multiple dark, pleomorphic nuclei; these represent cytotrophoblastic and syncytiotrophoblastic

differentiation, respectively. The hormone hCG can be identified with immunohistochemical staining.

Teratomas represent differentiation of neoplastic germ cells along somatic cell lines.

Grossly There are firm masses that on cut surface often contain cysts and recognizable areas of cartilage.

Microscopically, three major variants of pure teratoma are recognized:

1. Mature teratomas contain fully differentiated tissues from one or more germ cell layers (e.g., neural tissue,

cartilage, adipose tissue, bone, and epithelium) in a haphazard array.

2. Immature teratomas, in contrast, contain immature somatic elements reminiscent of those in developing fetal

tissue.

3. Teratomas with somatic-type malignancies are characterized by the development of frank malignancy in

preexisting teratomatous elements, usually in the form of a squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma.

Pure teratomas in prepubertal males are usually benign. In adults, teratomas metastasize in as many as one

third of cases. As with other germ cell tumors, testicular teratomas in adults often contain other malignant germ

cell elements and therefore should be generally regarded as malignant neoplasms.

Mixed germ cell tumors account for 40% of all testicular germ cell neoplasms. Combinations of any of the

described patterns may occur in mixed tumors, the most common of which is a combination of teratoma,

embryonal carcinoma, and yolk sac tumors.

Clinically, testicular germ cell tumors are divided in to two broad categories:

1. Seminomas and

2. Non-seminomatous tumors

These two groups of tumors have somewhat distinctive clinical presentation and natural history. Individuals

with testicular germ cell neoplasms present most frequently with painless testicular enlargement. However,

some tumors, especially nonseminomatous germ cell neoplasms, may have widespread metastases at diagnosis,

in the absence of a palpable testicular lesion. Seminomas often remain confined to the testis for prolonged

intervals and may reach considerable size before diagnosis. Metastases are most commonly encountered in the

iliac and para-aortic lymph nodes. Hematogenous metastases occur later. In contrast, nonseminomatous germ

cell neoplasms tend to metastasize earlier, by both lymphatic and hematogenous routes. Hematogenous

metastases are most common in the liver and lungs.

Testicular germ cell neoplasms are staged as follows:

Stage I: Tumor confined to the testis

Stage II: Regional lymph node metastases only

Stage III: Nonregional lymph node and/or distant organ metastases

Assay of tumor markers secreted by tumor cells is important in the clinical evaluation and staging of germ cell

neoplasms.

1. HCG, produced by neoplastic syncytiotrophoblastic cells, is always elevated in patients with

choriocarcinoma. Other germ cell tumors, including seminoma, may also contain syncytiotrophoblastic cells

without cytotrophoblastic elements and hence up to 25% of seminomas secrete hCG.

2. AFP is normally synthesized by the yolk sac and several other fetal tissues. Germ cell tumors containing

elements of yolk sac (endodermal sinus) often produce AFP; in contrast to hCG, the presence of AFP is a

reliable indicator of the presence of a nonseminomatous component to the germ cell neoplasm, because yolk sac

elements are not found in pure seminomas.

Because mixed patterns are common, most nonseminomatous tumors have elevations of both HCG and AFP. In

addition to their role in the primary diagnosis and staging of testicular germ cell tumors, serial determinations

of HCG and AFP are useful for monitoring patients for persistent or recurrent tumor after therapy.

THE PROSTATE

PROSTATITIS may be acute or chronic.

1. Acute bacterial prostatitis is caused by the same organisms associated with acute UTIs, particularly

Escherichia coli. Most patients with acute prostatitis also have concomitant acute urethritis and cystitis. In

these cases, organisms may reach the prostate by direct extension from the urethra or urinary bladder.

Alternatively prostatitis may complicate infections from distant sites through the blood.

2. Chronic prostatitis may follow episodes of acute prostatitis, or may develop insidiously, without previous

episodes of acute infection. In some cases of chronic prostatitis bacteria can be isolated (chronic bacterial

prostatitis). In other instances the presence of an increased number of leukocytes in prostatic secretions

confirms prostatic inflammation, but bacteriologic findings are negative (chronic abacterial prostatitis), which

account for most cases of chronic prostatitis. Several nonbacterial agents implicated in the pathogenesis of

nongonococcal urethritis, including Chlamydia trachomatis.

Pathological features

Acute prostatitis: there is an acute, neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate, congestion, and stromal edema.

Neutrophils are initially within the prostatic glands but as the infection progresses, they destroy glandular

epithelium and extends into the surrounding stroma, resulting in the formation of microabscesses. Grossly

visible abscesses can develop with extensive tissue destruction, e.g. in diabetic patients.

Chronic prostatitis: evidence of tissue destruction and fibroblastic proliferation, along with the presence of

inflammatory cells, such as lymphocytes & neutrophils, is required for a histologic diagnosis of chronic

prostatitis.

3. Granulomatous prostatitis is a variant of chronic prostatitis, it is not a single disease but instead a

morphologic reaction to a variety of insults. It may be seen

1. With systemic inflammatory diseases (disseminated TB, sacoidosis, fungal infections).

2. As a nonspecific reaction to inspissated prostatic secretions

3. After transurethral resection of prostatic tissue.

Microscopically, there are multinucleated giant cells and variable numbers of foamy histiocytes, sometimes

accompanied by eosinophils. Caseous necrosis is only seen in the setting of tuberculous prostatitis.

Clinical features

Prostatitis is manifested as dysuria, frequency, lower back pain, and poorly localized suprapubic or pelvic pain.

The prostate may be enlarged and tender, particularly in acute prostatitis with often fever and leukocytosis.

Chronic prostatitis, even if asymptomatic, may become a reservoir for organisms capable of causing UTIs.

Chronic bacterial prostatitis, therefore, is one of the most important causes of recurrent urinary tract infection

in men.

BENIGN PROSTATIC HYPERPLASIA (BPH) (Nodular hyperplasia of the prostate)

The normal prostate consists of glandular and stromal elements surrounding the urethra. The prostatic

parenchyma can be divided into the following biologically distinct zones:

1. Peripheral

2. Central

3. Transitional, and

4. Periurethral zones.

The types of proliferative lesions are different in each zone. For example, most hyperplastic lesions arise in the

inner transitional and central zones of the prostate, while most carcinomas arise in the peripheral zones.

BPH is an extremely common & affects a significant number of men by the age of 40, and its frequency rises

progressively with age, reaching 90% by the eighth decade. BPH is characterized by proliferation of both

stromal and epithelial elements, with resultant enlargement of the gland and, in some cases, urinary obstruction.

Androgens have a central role in the pathogenesis of BPH. Dihydrotestosterone. (DHT) is derived from

testosterone through the action of 5α-reductase & appears to be major hormonal stimulus for stromal and

glandular proliferation in men with nodular hyperplasia. DHT binds to nuclear androgen receptors and, in turn,

stimulates synthesis of DNA, RNA, growth factors, and other cytoplasmic proteins, leading to hyperplasia. This

is the base for the current use of 5α-reductase inhibitors in the treatment of symptomatic nodular hyperplasia.

Local, intra-prostatic concentrations of androgens and androgen receptors contribute to the pathogenesis of this

condition. Age-related increases in estrogen levels that may increase the expression of DHT receptors on

prostatic parenchymal cells, thereby functioning in the pathogenesis of nodular hyperplasia.

Gross features

BPH arises mostly in the inner, peri-urethral glands of the prostate, particularly from those that lie above the

verumontanum.

The affected prostate is enlarged.

The cut surface contains many well-circumscribed nodules. The nodules may have a solid appearance or may

contain cystic spaces, the latter corresponding to dilated glandular elements seen in histologic sections.

The urethra is usually compressed by the hyperplastic nodules, often to a slitlike orifice.

In some cases, hyperplastic glandular and stromal elements lying just under the proximal prostatic urethra

may project into the bladder lumen as a pedunculated mass, resulting in a ball-valve type of urethral

obstruction.

Microscopic features

The hyperplastic nodules are composed of varying proportions of proliferating glandular elements and

fibromuscular stroma.

The hyperplastic glands are lined by tall, columnar epithelial cells and a peripheral layer of flattened basal

cells; crowding of the proliferating epithelium results in the formation of papillary projections in some

glands.

The glandular lumina often contain inspissated, proteinaceous secretory material, termed corpora amylacea.

The glands are surrounded by proliferating stromal elements.

Areas of infarction are frequent in advanced cases of BPH and are accompanied by foci of squamous

metaplasia in adjacent glands.

Clinical manifestations of BPH occur in only 10% of men with the disease. Because nodular hyperplasia

preferentially involves the inner portions of the prostate, its most common manifestations are those of lower

urinary tract obstruction. These include difficulty in starting the stream of urine (hesitancy) and intermittent

interruption of the urinary stream while voiding. Some may develop complete urinary obstruction, with

resultant painful distention of the bladder and, if neglected, hydronephrosis. Symptoms of obstruction are

frequently accompanied by urinary urgency, frequency, and nocturia, all indicative of bladder irritation. The

combination of residual urine in the bladder and chronic obstruction increases the risk of urinary tract

infections.

CARCINOMA OF THE PROSTATE

This is the most common visceral cancer in males and the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths

in men older than 50 years of age, after carcinoma of the lung. The peak incidence is around the age of 70

years. Hidden (Latent) cancers of the prostate are even more common than those that are clinically apparent,

with an overall frequency of more than 50% in men older than 80 years of age.

Hormones, genes, and environment are thought to be of pathogenetic importance:

A. Androgens; their role in prostatic carcinogenesis is supported by the following observations

1. Cancer of the prostate does not develop in males castrated before puberty.

2. The growth of many prostatic carcinomas can be inhibited by orchiectomy or by the administration of

estrogens such as diethylstilbestrol.

B. Hereditary & Racial contributions are supported by

1. The increased risk of the disease among first-degree relatives of patients with prostate cancer.

2. Symptomatic carcinoma is more common and occurs at an earlier age in blacks & Asians. Whether such

racial differences occur as a consequence of genetic influences &/or environmental factors remains unknown.

However, the frequency of latent (incidental) prostatic cancers is similar in all races, suggesting that race is

more importantly in the growth of established lesions than in the initial development of carcinoma.

In familial cases, several susceptibility loci on chromosome 1 have been identified.

C. Environmental influences is suggested by the increased frequency of prostatic carcinoma in certain

industrial settings and by significant geographic differences in the incidence of the disease. Carcinoma of the

prostate is particularly common in Scandinavian countries and relatively uncommon in Japan and certain other

Asian countries. Males immigrating from low-risk to high-risk areas maintain a lower risk of prostate cancer;

the risk of disease is intermediate in subsequent generations, in keeping with an environmental influence on the

development of this disease. A diet high in animal fat has been suggested as a risk factor.

Gross features:

The majority of prostate cancers (80%) arise in the outer (peripheral) glands and hence may be palpable as

irregular hard nodules by rectal digital examination. Because of the peripheral location, prostate cancer is less

likely to cause urethral obstruction in its initial stages than is nodular hyperplasia.

Early lesions typically appear as ill-defined masses just beneath the capsule of the prostate.

On cut surface, foci of carcinoma appear as firm, gray-white to yellow lesions that infiltrate the adjacent

native prostatic tissues with ill-defined margins.

Metastases to regional pelvic lymph nodes may occur early.

Locally advanced cancers often infiltrate the seminal vesicles and periurethral zones of the prostate and may

invade the adjacent soft tissues and the wall of the urinary bladder. Denonvilliers fascia, the connective tissue

layer separating the lower genitourinary structures from the rectum, usually prevents growth of the tumor

posteriorly. Invasion of the rectum therefore is less common than is invasion of other contiguous structures.

Microscopic features:

Most carcinomas are adenocarcinomas with variable degrees of differentiation.

The better differentiated lesions are composed of small glands that infiltrate the adjacent stroma in an

irregular, haphazard fashion.

In contrast to normal and hyperplastic prostate, the glands in carcinomas

1. Lie "back to back" and appear to dissect sharply though the native stroma

2. Are lined by a single layer of cuboidal cells with conspicuous nucleoli; the basal cell layer seen in normal or

hyperplastic glands is absent.

With increasing degrees of anaplasia, irregular glandular, papillary or cribriform epithelial structures, and, in

extreme cases, sheets of poorly differentiated cells are present.

Glands adjacent to areas of invasive carcinoma of the prostate often contain foci of epithelial atypia, or

prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN).

Because of its frequent coexistence with infiltrating carcinoma, PIN has been suggested as a probable precursor

to carcinoma of the prostate. PIN has been subdivided into high-grade and low-grade patterns, depending on the

degree of atypia. Importantly, high-grade PIN shares molecular changes with invasive carcinoma, lending

support to the argument that PIN is an intermediate between normal and frankly malignant tissue.

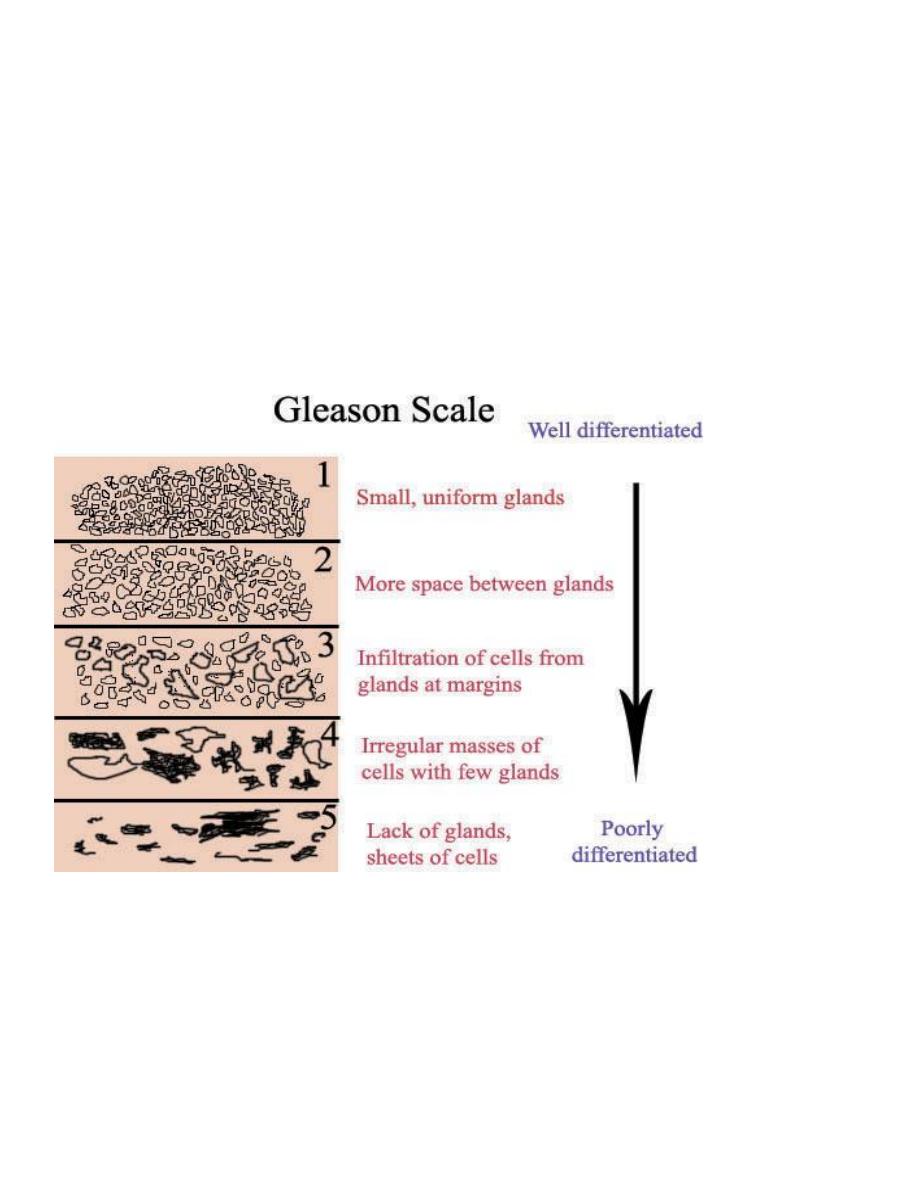

A number of histologic grading schemes have been proposed for carcinoma of the prostate. They are based on

features such as the degree of glandular differentiation, the architecture of the neoplastic glands, nuclear

anaplasia, and mitotic activity. A commonly used method for grading is the Gleason system, which has proved

to correlate reasonably well with both the stage of prostatic carcinoma and its prognosis.

Clinically, 10% of carcinomas are localized and discovered unexpectedly during histologic examination of

tissues removed for nodular hyperplasia. Because most cancers begin in the peripheral regions of the prostate,

they may be discovered during digital rectal examination. More extensive disease may produce local discomfort

and evidence of lower urinary tract obstruction. PR exam. in such cases reveals a hard, fixed prostate.

Aggressive carcinomas may first come to attention through the presence of metastases. Bone metastases,

particularly to the axial skeleton, are common and may cause either osteolytic (destructive) or, more commonly,

osteoblastic (bone-producing) lesions. The presence of osteoblastic metastases in an older male is strongly

suggestive of advanced prostatic carcinoma.

Assay of serum levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) has gained widespread use in the diagnosis of early

carcinomas. PSA is proteolytic enzyme produced by both normal and neoplastic prostatic epithelium.

Traditionally, a serum PSA level of 4.0 ng/L has been used as the upper limit of normal. Cancer cells produce

more PSA, but any condition that disrupts the normal architecture of the prostate, including adenocarcinoma,

BPH, and prostatitis, may also cause an elevation in serum levels of PSA. Moreover, in some cases of cancer of

the prostate, especially those confined to the prostate, serum PSA is not elevated. Because of these problems,

PSA is of limited value when used as an isolated screening test for cancer of the prostate. However, it has a

much more value when it is used in conjunction with other procedures, such as digital rectal examination,

transrectal sonography, and needle biopsy. In contrast to its limitations as a diagnostic screening test, serum

PSA concentration is of great value in monitoring patients after treatment for prostate cancer, with rising levels

after therapy indicative of recurrence and/or the development of metastases.

Grading and staging of prostate Adenocarcinoma:

Grading:

A number of histologic grading schemes have been proposed for carcinoma of the prostate. They are based on

features such as the degree of glandular differentiation, the architecture of the neoplastic glands, nuclear

anaplasia, and mitotic activity. A commonly used method for grading is the Gleason system, which has proved

to correlate reasonably well with both the stage of prostatic carcinoma and its prognosis.

Staging of the extent of disease has an important role in the evaluation and treatment of prostatic carcinoma.

The anatomic extent of disease and the histologic grade influence the therapy for prostate cancer and correlate

well with prognosis. Carcinoma of the prostate is treated with various combinations of surgery, radiation

therapy, and hormonal manipulations. Most prostate cancers are androgen sensitive and are inhibited to some

degree by surgical or pharmacologic castration, estrogens, and androgen receptor-blocking agents. These all

have been used to control the growth of disseminated lesions.

The prognosis for patients with limited-stage disease is favorable: more than 90% of patients with stage T1 or

T2 lesions (localized to the prostate) survive 10 years or longer. The outlook for patients with disseminated

disease remains poor, with 10-year survival rates in this group ranging from 10% to 40%.