SKELETAL MUSCLES

The motor unit consists of a motor neuron in the brain or spinal cord, it is associated peripheral axon and distal

neuromuscular junction, and finally, the skeletal muscle fibers that are innervated. Depending on the nature of

the nerve fiber doing the enervation the associated skeletal muscle develops into one of two major

subpopulations; type I "slow twitch" or type II "fast twitch" fibers. The different fibers can be identified using

specific staining techniques. A single "type I" or "type II" neuron will innervate multiple muscle fibers and

these fibers are usually randomly scattered in a "checkerboard pattern" within a circumscribed area within the

larger muscle.

Diseases that affect skeletal muscle can involve any portion of the motor unit; these include

1. Disorders of the motor neuron or axon (neurogenic atrophy)

2. Abnormalities of the neuromuscular junction (e.g. myasthenia gravis)

2. Disorders of the skeletal muscle itself (myopathies)

Muscle Atrophy is a non-specific response in a variety of muscle disorders. It is characterized by abnormally

small myofibers; the type of fibers affected by the atrophy, their distribution in the muscle, and their specific

morphology help identify the etiology of the atrophic changes.

Neurogenic Atrophy is due to lack of normal enervation. The loss of a single neuron will affect all muscle

fibers in a motor unit, so that the atrophy tends to be scattered over the field. It is characterized by involvement

of both fiber types, and by clustering of myofibers into small groups

Muscular Dystrophy

The muscular dystrophies are “a heterogeneous group of inherited disorders, often presenting in childhood,

characterized by progressive degeneration of muscle fibers leading to muscle weakness and wasting.” In

advanced cases muscle fibers are replaced by fibrofatty tissue. This histologic feature distinguishes dystrophies

from myopathies, which also present with muscle weakness.

X-Linked Muscular Dystrophy: Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD)

This X-linked inherited disease is the most common & the most severe form of muscular dystrophy. It becomes

clinically evident by age 5, with progressive weakness leading to wheelchair dependence by age 10 to 12 years,

and death by the early 20s. The same gene is involved in a related but milder form designated Becker muscular

dystrophy.

Microscopic features (Fig. 12-33)

Marked variation in muscle fiber size, caused by hypertrophy and atrophy.

The residual muscle fibers show degenerative & regenerative changes (the former is evidenced by fiber

splitting and necrosis & the latter by sarcoplasmic basophilia & nuclear enlargement).

Connective tissue is increased throughout the muscle.

In the late stages of the disease, extensive fiber loss and adipose tissue infiltration are present.

The definitive diagnosis is based on the demonstration of abnormal staining for dystrophin in

immunohistochemical preparations.

DMD is caused by abnormalities in the dystrophin gene located on the short arm of the X chromosome. In

affected families, females are carriers; they are clinically asymptomatic.

Boys with DMD show delayed walking. There is enlargement of the calf muscles associated with weakness, a

phenomenon termed pseudohypertrophy; this is an important clinical finding. The increased muscle bulk is

caused initially by an increase in the size of the muscle fibers and then, as the muscle atrophies, by an increase

in fat and connective tissue. Pathologic changes are also found in the heart, and patients may develop heart

failure or arrhythmias. Serum creatine kinase is elevated during the first decade of life. Death results from

respiratory insufficiency, pulmonary infection, and heart failure.

Skeletal Muscle Tumors

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common soft tissue sarcoma of childhood and adolescence, usually appearing

before age 20. They occur most commonly in the head and neck or genitourinary tract.

Chromosomal translocations are found in most cases; the more common t(2;13) translocation fuses the PAX3

gene (controls skeletal muscle differentiation & development) on chromosome 2 with the FKHR gene on

chromosome 13. The hybrid PAX3-FKHR protein probably involves dysregulation of muscle differentiation.

Gross features

Tumors arising near the mucosal surfaces of the bladder or vagina, can present as soft, gelatinous, grapelike

masses, designated sarcoma botryoides.

In other cases they are deceptively demarcated or infiltrative grayish-white to brownish masses.

Microscopical features

Rhabdomyosarcoma is histologically subclassified into the embryonal, alveolar, and pleomorphic variants.

The rhabdomyoblast is the diagnostic cell in all types; it exhibits granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, and may

be round or elongated; the latter are known as tadpole or strap cells and may contain cross-striations visible

by light microscopy.

The diagnosis of rhabdomyosarcoma is based on the demonstration of skeletal muscle differentiation, either

in the form of sarcomeres under the electron microscope or by immunohistochemical demonstration of

muscle-associated antigens such as desmin and muscle-specific actin.

Rhabdomyosarcomas are aggressive neoplasms. Location and the histologic variant of the tumor influence

survival; embryonal, pleomorphic, and alveolar variants have progressively worsening prognoses. The

malignancy is curable in almost two-thirds of children, but adults do much more poorly.

SOFT TISSUE TUMORS

Fatty Tumors

1. Lipomas are benign tumors of fat, and are the most common soft tissue tumors of adulthood. Most lipomas

are solitary lesions. Lipomas can be subclassified based on their histologic features (e.g., conventional,

myolipoma, spindle cell, myelolipoma, pleomorphic, angiolipoma), and/or characteristic chromosomal

rearrangements. Most lipomas are mobile, slowly enlarging, painless masses. They are usually seen in adults

age 40+; associated with obesity; there are no gender differences. They are rare in children. Multiple lipomas

are more common in women. The condition is often familial, & may be associated with neurofibromatosis &

multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes. Lipomas mostly involve the subcutaneous tissue of the trunk, back,

shoulder, neck, proximal extremities but are rare on hands, feet, face, &in retroperitoneum

Pathological features

Conventional lipomas (the most common subtype) are soft, yellow, well-encapsulated masses

They can vary considerably in size.

Microscopically, they consist of mature fat cells with no pleomorphism.

2. Liposarcoma is a malignant neoplasm of adipocytes. These tumors occur most commonly in the 40 to 60

years of age & mostly in the deep soft tissues (cf. lipoma) or in visceral sites. The prognosis of liposarcomas is

greatly influenced by the histologic subtype; well-differentiated and myxoid variants tend to grow in a fairly

indolent fashion and have a more favorable outlook than do the more aggressive round cell and pleomorphic

variants, which tend to recur after excision and metastasize to lungs. A t(12;16) chromosomal translocation is

associated with myxoid liposarcomas; the rearrangement affects a transcription factor that plays a role in normal

adipocyte differentiation.

Pathological features

Usually they are relatively well-circumscribed large masses.

Several different histologic subtypes are recognized, including two low-grade variants, the well-

differentiated liposarcoma and the myxoid liposarcoma, the latter characterized by abundant, mucoid

extracellular matrix.

Some well-differentiated lesions can be difficult to distinguish histologically from lipomas, whereas very

poorly differentiated tumors can resemble various other high-grade malignancies.

In most cases, cells indicative of fatty differentiation are present. Such cells are known as lipoblasts; they

recapitulate fetal fat cells with cytoplasmic lipid vacuoles that scallop the nucleus.

Fibrous Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions

Reactive Proliferations

1. Nodular Fasciitis is a self-limited, reactive fibroblastic proliferation that typically occurs in adults on the

volar aspect of the forearm. Patients characteristically present with a several-week history of a solitary, rapidly

growing mass. Preceding trauma is noted in up to 15% of cases.

Pathological features

Characteristically, the lesion is several centimeters in greatest dimension and nodular.

Mcroscopically, it is richly cellular and consists of plump, randomly arranged, immature-appearing

fibroblasts in an abundant myxoid stroma.

The cells vary in size and shape (spindle to stellate) and have conspicuous nucleoli and numerous mitoses.

2. Myositis Ossifican is distinguished from other fibroblastic proliferations by the presence of metaplastic

bone. It usually develops in the proximal muscles of the extremities in athletic adolescents and young adults

after trauma. The involved area is initially swollen and painful, eventually evolving into a painless, hard, well-

demarcated mass. It is vital to distinguish the lesion from extra-skeletal osteosarcoma.

3. Fibromatoses are a group of fibroblastic proliferations distinguished by their tendency to grow in an

infiltrative fashion and, in many cases, to recur after surgical removal. Although some lesions are locally

aggressive, they do not metastasize. The fibromatoses are divided into two major clinicopathologic groups:

superficial and deep.

The superficial fibromatoses arise in the superficial fascia and include such entities as palmar fibromatosis

(Dupuytren contracture) and penile fibromatosis (Peyronie disease). Superficial lesions are genetically distinct

from their deep-seated cousins and are generally more innocuous; they also come to clinical attention earlier,

because they cause deformity of the involved structure. The deep fibromatoses include the so-called desmoid

tumors that arise in the abdominal wall & muscles of the trunk and extremities, and within the abdominal cavity

(mesentery and pelvic walls). Deep fibromatoses tend to grow in a locally aggressive manner and recur after

excision. These tumors are gray-white, firm to rubbery, poorly demarcated, infiltrative masses 1 to 15 cm in

greatest dimension. Microscopically, they are composed of plump cells arranged in broad sweeping fascicles

that penetrate the adjacent tissue.

Fibrosarcoma is a malignant neoplasm composed of fibroblasts. Most occur in adults, typically in the deep

tissues of the thigh and retroperitoneal area. As with other sarcomas, fibrosarcomas often recur locally after

excision (>50% of cases) and can metastasize hematogenously (>25% of cases), usually to the lungs.

Pathological features

These unecapsulated, infiltrative sarcomas show frequently areas of hemorrhage and necrosis.

Microscopically, the low-grade tumors may closely resemble fibromatosis; less differentiated examples

show densely packed spindled cells growing in a herringbone fashion, there are frequent mitoses, and

necrosis.

Fibrohistiocytic Tumors

These are composed of a mixture of fibroblasts and phagocytic, lipid-laden cells resembling activated

macrophages. The neoplastic cells are most likely fibroblasts. Nevertheless, a significant number of such tumors

actually derive from other mesenchymal cell types. Thus, the term fibrohistiocytic, especially in regard to the

malignant variants, should be considered descriptive and not necessarily referring to a specific cellular origin.

These tumors are divided into benign, of intermediate malignant potential, frankly malignant.

1. Benign Fibrous Histiocytoma (Dermatofibroma) are relatively common benign lesions in adults presenting

as small (<1 cm) mobile nodules in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. Microscopically, the lesion consists of

bland, interlacing spindle cells admixed with foamy, lipid-rich histiocyte-like cells. The borders of the lesions

tend to be infiltrative. The pathogenesis of these lesions is uncertain.

2. Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma (MFH) is a term rather loosely applied to a variety of soft tissue sarcomas

characterized by considerable cytologic pleomorphism, the presence of bizarre multinucleate cells, and

storiform architecture. Despite the name, the phenotype of many such tumors is fibroblastic and not histiocytic.

Nevertheless, it is also important to note that several tumors diagnosed as MFH actually exhibit markers for

cells of other origin (e.g., smooth muscle cells, adipocytes, skeletal muscle cells) and are therefore more

appropriately classified as leiomyosarcomas, liposarcomas, etc. MFH exhibiting fibroblastic differentiation are

usually large (5-20 cm), gray-white unencapsulated masses that often appear deceptively circumscribed. They

usually arise in the musculature of the proximal extremities or in the retroperitoneum. Most of these tumors are

extremely aggressive, recur unless widely excised, and have a metastatic rate of 30% to 50%.

Smooth Muscle Tumors

1. Leiomyomas are common, well-circumscribed neoplasms that can arise from smooth muscle cells anywhere

in the body, but are encountered most commonly in the uterus.

2. Leiomyosarcomas (15% of soft tissue sarcomas). They occur in adults, more commonly females. Deep soft

tissues of the extremities and retroperitoneum are common sites. Microscopically, they show spindle cells with

cigar-shaped nuclei arranged in interweaving fascicles. Superficial leiomyosarcomas are usually small and have

a good prognosis, whereas retroperitoneal tumors are large, cannot be entirely excised, and cause death by both

local extension and metastatic spread.

Synovial Sarcoma (10% of all soft tissue sarcomas)

The cell of origin is unclear and is most certainly not a synoviocyte. Reflecting a non-joint origin, 90% of

synovial sarcomas are not intra-articular but rather paraarticular. They are typically seen in the 20-40 years of

age. Most develop in deep soft tissues around the large joints of the extremities, especially around the knee.

Most synovial sarcomas show a characteristic t(X;18) translocation, which relates to prognosis.

Microscopically, synovial sarcomas may be biphasic or monophasic. Classic biphasic synovial sarcoma exhibits

differentiation of tumor cells into both epithelial-like cells and spindle cells. The epithelial cells are cuboidal to

columnar and form glands or grow in solid cords or aggregates. The spindle cells are arranged in densely

cellular fascicles that surround the epithelial cells. Immunohistochemistry is helpful, because the tumor cells are

positive for keratin and epithelial membrane antigen. Common metastatic sites are lung, bone, and regional

lymph nodes. Only 10% to 30% live for more than 10 years.

PATHOLOGY OF THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

BONES & JOINTS

CONGENITAL DISEASES OF BONE

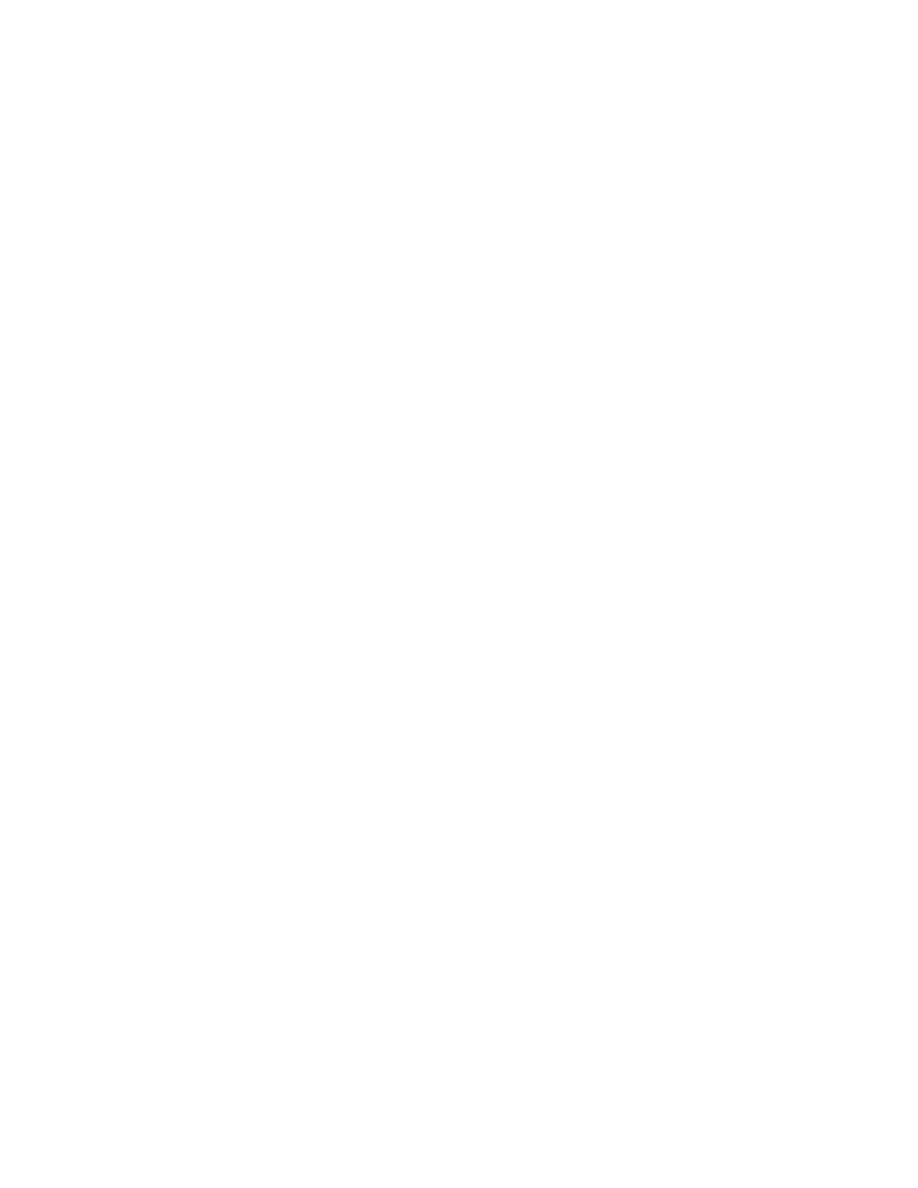

Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI) (Brittle bone diseases) is a group of hereditary

disorders caused by gene mutations that eventuate in defective synthesis of and thus

premature degradation of type I collagen. The fundamental abnormality in all forms

of OI is too little bone, resulting in extreme susceptibility to fractures. The bones

show marked cortical thinning and attenuation of trabeculae.

Extraskeletal manifestations also occur because type I collagen is a major component

of extracellular matrix in other parts of the body. The classic finding of blue sclerae is

attributable to decreased scleral collagen content; this causes a relative transparency

that allows the underlying choroid to be seen. Hearing loss can be related to

conduction defects in the middle and inner ear bones, and small misshapen teeth are a

result of dentin deficiency.

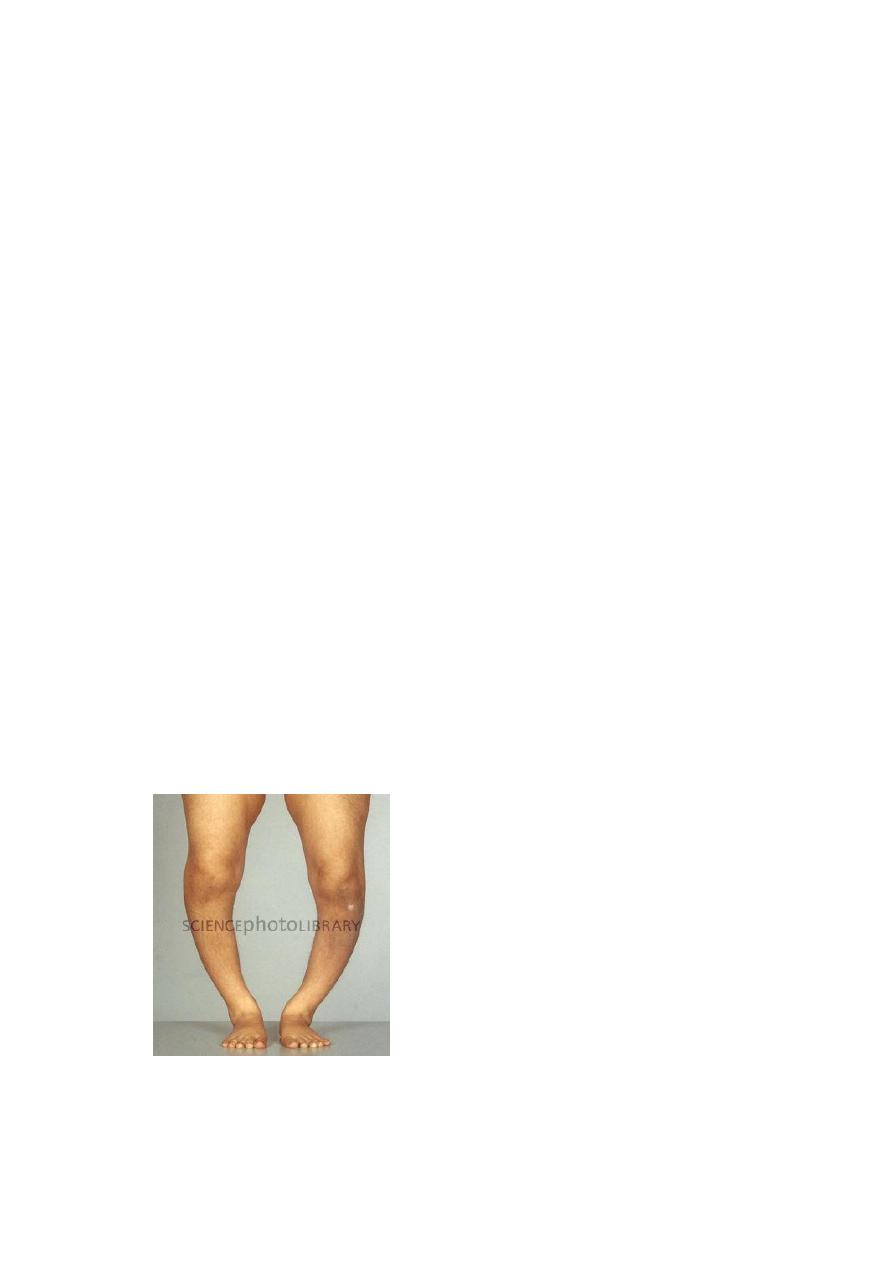

Achrondroplasia is a major cause of dwarfism. The underlying etiology is a point

mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor, which causes inhibition of

chondrocyte proliferation, which is associated with suppression of the normal

epiphyseal growth plate expansion. Thus, long bone growth is markedly shortened.

The most conspicuous changes include disproportionate shortening of the proximal

extremities,

bowing

of

the

legs,

and

a

lordotic

posture.

ACQUIRED DISEASES OF BONE DEVELOPMENT

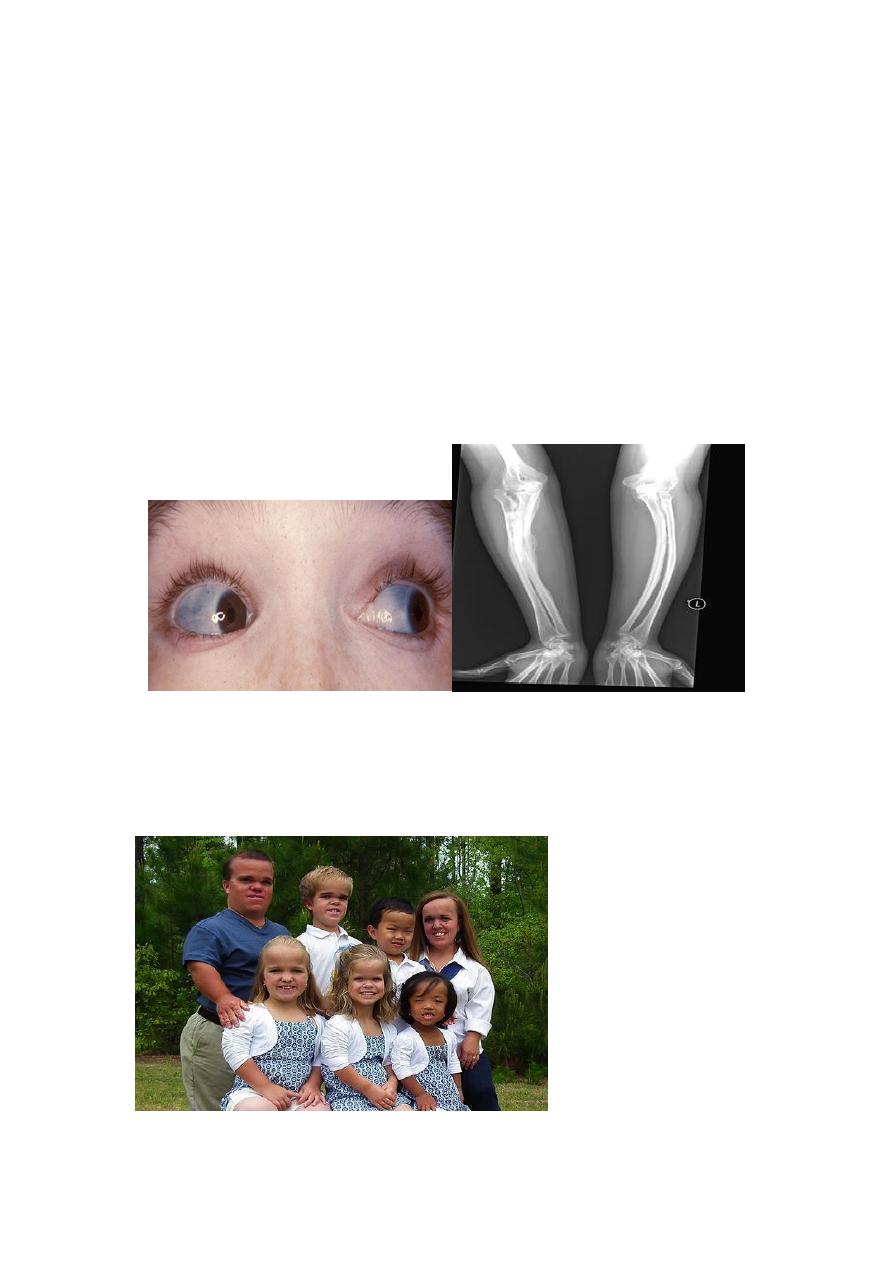

Osteoporosis is characterized by increased porosity of the skeleton resulting from

reduced bone mass. The disorder may be localized to a certain bone (s), as in disuse

osteoporosis of a limb, or generalized involving the entire skeleton. Generalized

osteoporosis may be primary, or secondary.

Primary generalized osteoporosis

Postmenopausal

Senile

Secondary generalized osteoporosis

Senile and postmenopausal osteoporosis are the most common forms. In the fourth

decade in both sexes, bone resorption begins to overrun bone deposition. Such losses

generally occur in areas containing abundant cancelloues bone such as the vertebrae

& femoral neck. The postmenopausal state accelerates the rate of loss; that is why

females are more susceptible to osteoporosis and its complications.

Gross features

Because of bone loss, the bony trabeculae are thinner and more widely separated

than usual. This leads to obvious porosity of otherwise spongy cancellous bones.

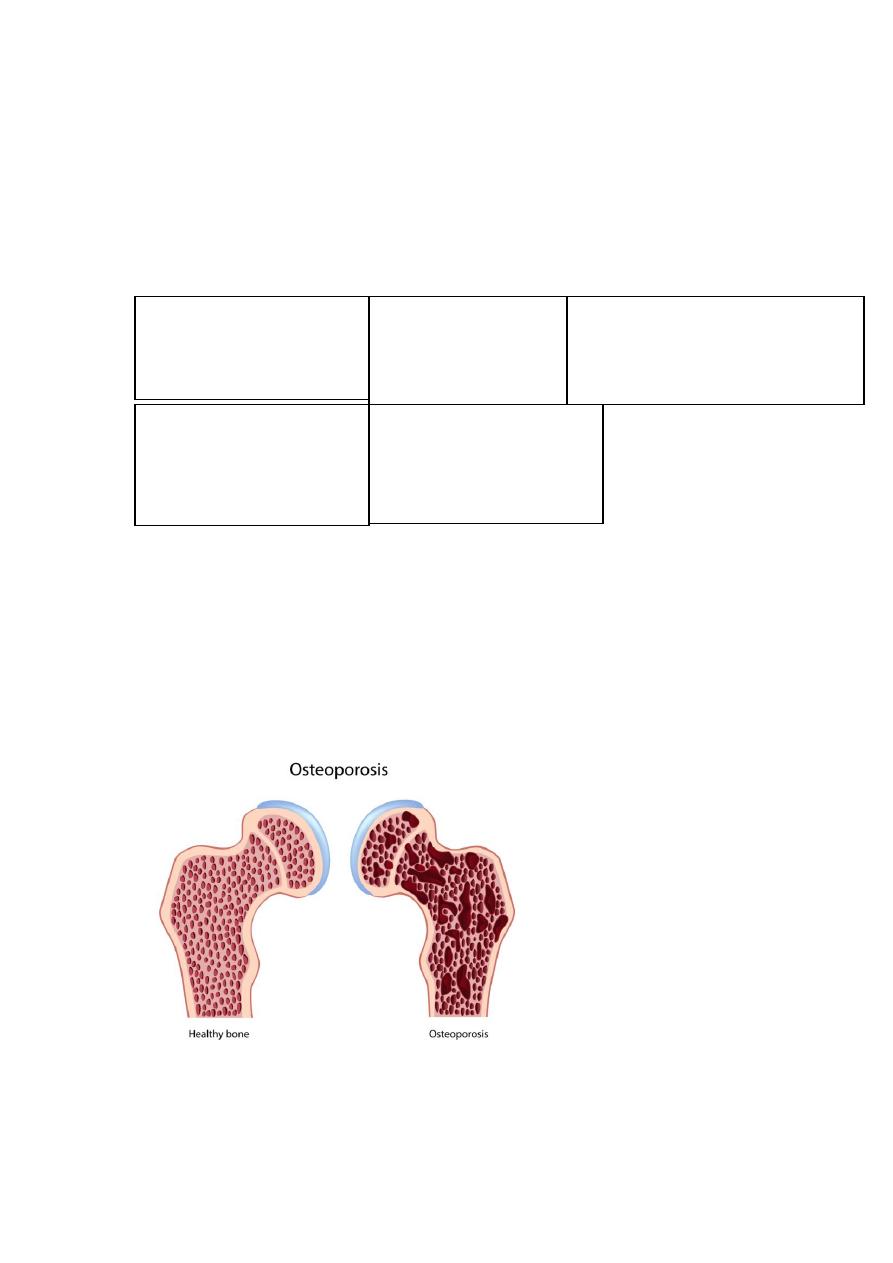

Microscopic features

There is thinning of the trabeculae and widening of Haversian canals.

B. Neoplasia

Multiple myeloma

Carcinomatosis

A. Endocrine disorders

Hyperparathyroidism

Hypo or hyperthyroidism

Others

C. Gastrointestinal disorders

Malnutrition & malabsorption

Vit D & C deficiency

Hepatic insufficiency

D. Drugs

Corticosteroids

Anticoagulants

Chemotherapy

Alcohol

E. Miscellaneous

osteogenesis imperfecta

immobilization

pulmonary disease

The mineral content of the thinned bone is normal, and thus there is no alteration in

the ratio of minerals to protein matrix.

Etiology & Pathogenesis

Osteoporosis involves an imbalance of bone formation, bone resorption, &

regulation of osteoclast activation. It occurs when the balance tilts in favor of

resorption.

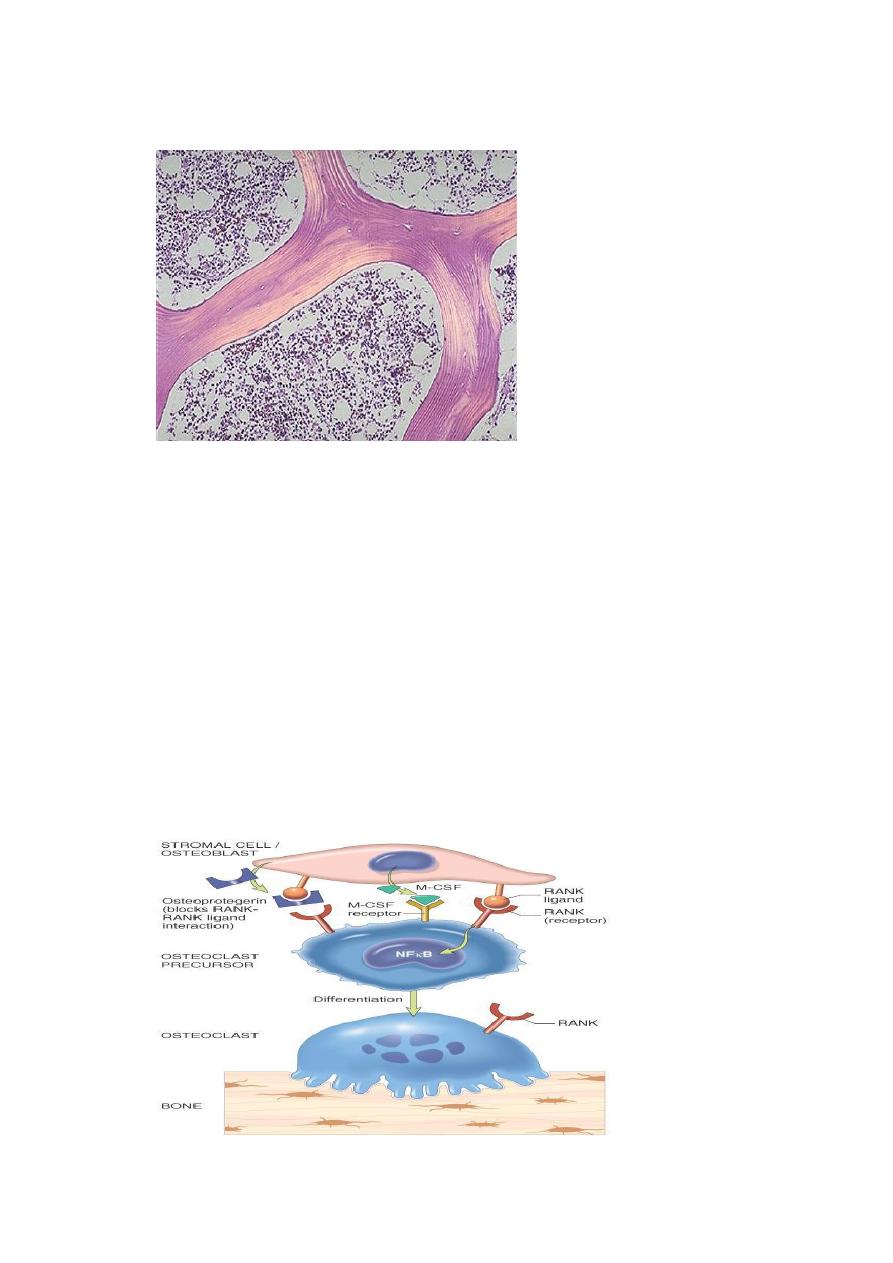

Osteoclasts (as macrophages) bear receptors (called RANK receptors) that when

stimulated activate the nuclear factor (NFκB) transcriptional pathway. RANK

ligand synthesized by bone stromal cells and osteoblasts activates RANK. RANK

activation converts macrophages into bone-crunching osteoclasts and is therefore

a major stimulus for bone resorption.

Osteoprotegerin (OPG) is a receptor secreted by osteoblasts and stromal cells,

which can bind RANK ligand and by doing so makes the ligand unavailable to

activate RANK, thus limiting osteoclast bone-resorbing activity.

Dysregulation of RANK, RANK ligand, and OPG interactions seems to be a major

contributor in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Such dysregulation can occur for a

variety of reasons, including aging and estrogen deficiency

Influence of age: with increasing age, osteoblasts synthetic activity of bone matrix

progressively diminished in the face of fully active osteoclasts.

The hypoestrogenic effects: the decline in estrogen levels associated with

menopause correlates with an annual decline of as much as 2% of cortical bone

and 9% of cancellous bone. The hypoestrogenic effects are attributable in part to

augmented cytokine production (especially interleukin-1 and TNF). These translate

into increased RANK-RANK ligand activity and diminished OPG.

Physical activity: reduced physical activity increases bone loss. This effect is

obvious in an immobilized limb, but also occurs diffusely with decreased physical

activity in older individuals.

Genetic factors: these influence vitamin D receptors efficiency, calcium uptake, or

PTH synthesis and responses.

Calcium nutritional insufficiency: the majority of adolescent girls (but not boys)

have insufficient dietary intake of calcium. As a result, they do not achieve the

maximal peak bone mass, and are therefore likely to develop clinically significant

osteoporosis at an earlier age.

Secondary causes of osteoporosis: these include prolonged glucocorticoid therapy

(increases bone resorption and reduce bone synthesis.)

The clinical outcome of osteoporosis depends on which bones are involved. Thoracic

and lumbar vertebral fractures are extremely common, and produce loss of height

and various deformities, including kyphoscoliosis that can compromise respiratory

function. Pulmonary embolism and pneumonia are common complications of

fractures of the femoral neck, pelvis, or spine.

Paget Disease (Osteitis Deformans)

This unique bone disease is characterized by repetitive episodes of exaggerated,

regional osteoclastic activity (osteolytic stage), followed by exuberant bone formation

(mixed osteoclastic-osteoblastic stage), and finally by exhaustion of cellular activity

(osteosclerotic stage). The net effect of this process is a gain in bone mass; however,

the newly formed bone is disordered and lacks strength. Paget disease usually does

not occur until mid-adulthood but becomes progressively more common

thereafter.The axial skeleton and proximal femur are involved in the majority of

cases.

Complications include In patients with extensive disease, congestive heart

failure(hypervascularity of marrow tissue),cranial nerves impingement and rarely

bone sarcoma (usually osteogenic).

Rickets and Osteomalacia:

an excess of unmineralized matrix.

Rickets in growing children and osteomalacia in adults are skeletal diseases with

worldwide distribution. They may result from

1. Diets deficient in calcium and vitamin D

2. Limited exposure to sunlight (in heavily veiled women, and inhabitants of northern

climates with scant sunlight)

3. Renal disorders causing decreased synthesis of 1,25 (OH)

2

-D or phosphate

depletion

4. Malabsorption disorders.

Although rickets and osteomalacia rarely occur outside high-risk groups, milder forms

of vitamin D deficiency (also called vitamin D insufficiency) leading to bone loss and

hip fractures are quite common in the elderly.

Whatever the basis, a deficiency of vitamin D tends to cause hypocalcemia. When

hypocalcemia occurs, PTH production is increased, that ultimately leads to

restoration of the serum level of calcium to near normal levels (through mobilization

of Ca from bone & decrease in its tubular reabsorption) with persistent

hypophosphatemia (through increase renal exretion of phosphate); so mineralization

of bone is impaired or there is high bone turnover.

The basic derangement in both rickets and osteomalacia is an excess of unmineralized

matrix. This complicated in rickets by derangement of endochondral bone growth.

The following sequence ensues in rickets:

1. Overgrowth of epiphyseal cartilage with distorted, irregular masses of cartilage

2. Deposition of osteoid matrix on inadequately mineralized cartilage

3. Disruption of the orderly replacement of cartilage by osteoid matrix, with

enlargement and lateral expansion of the osteochondral junction

4. Microfractures and stresses of the inadequately mineralized, weak, poorly formed

bone

5. Deformation of the skeleton due to the loss of structural rigidity of the developing

bones

Gross features

The gross skeletal changes depend on the severity of the disease; its duration, & the

stresses to which individual bones are subjected.

During the nonambulatory stage of infancy, the head and chest sustain the greatest

stresses. The softened occipital bones may become flattened. An excess of osteoid

produces frontal bossing. Deformation of the chest results from overgrowth of

cartilage or osteoid tissue at the costochondral junction, producing the "rachitic

rosary." The weakened metaphyseal areas of the ribs are subject to the pull of the

respiratory muscles and thus bend inward, creating anterior protrusion of the

sternum (pigeon breast deformity). The pelvis may become deformed.

When an ambulating child develops rickets, deformities are likely to affect the

spine, pelvis, and long bones (e.g., tibia), causing, most notably, lumbar lordosis

and bowing of the legs

.

In adults the lack of vitamin D deranges the normal bone remodeling that occurs

throughout life. The newly formed osteoid matrix laid down by osteoblasts is

inadequately mineralized, thus producing the excess of persistent osteoid that is

characteristic of osteomalacia. Although the contours of the bone are not affected,

the bone is weak and vulnerable to gross fractures or microfractures, which are

most likely to affect vertebral bodies and femoral necks.

Hyperparathyroidism

Abnormally high levels of parathyroid hormone (PTH) cause hypercalcemia. This can

result from either primary or secondary causes. Primary hyperparathyroidism is

caused usually by a parathyroid adenoma, which is associated with autonomous PTH

secretion. Secondary hyperparathyroidism, on the other hand, can occur in the

setting of chronic renal failure. In either situation, the presence of excessive amounts

of this hormone leads to significant skeletal changes related to a persistently

exuberant osteoclast activity that is associated with increased bone resorption and

calcium mobilization. The entire skeleton is affected. PTH is directly responsible for

the bone changes seen in primary hyperparathyroidism, but in secondary

hyperparathyroidism additional influences also contribute. In chronic renal failure

there is inadequate 1,25-(OH)

2

-D synthesis that ultimately affects gastrointestinal

calcium absorption. The hyperphosphatemia of renal failure also suppresses renal α

1

-

hydroxylase, which further impair vitamin D synthesis; all these eventuate in

hypocalcemia, which stimulates excessive secretion of PTH by the parathyroid

glands, & hence elevation in PTH serum levels.

Bone changes include

Increased osteoclastic activity, with bone resorption. Cortical and trabecular bone

are lost and replaced by loose connective tissue.

Bone resorption is especially pronounced in the subperiosteal regions and produces

characteristic radiographic changes, best seen along the radial aspect of the middle

phalanges of the second and third fingers.

reduced bone mass, and hence are increasingly susceptible to fractures and bone

deformities.

Osteonecrosis (Avascular Necrosis)

Ischemic necrosis with resultant bone infarction occurs mostly due to fracture or after

corticosteroid use. Microscopically, dead bon trabevulae (characterized by empty

lacunae) are interspersed with areas of fat necrosis. The cortex is usually not affected

because of collateral blood supply; in subchondral infarcts, the overlying articular

cartilage also remains viable because the synovial fluid can provide nutritional

support. With time, osteoclasts can resorb many of the necrotic bony trabeculae; any

dead bone fragments that remain act as scaffolds for new bone formation, a process

called creeping substitution. Symptoms depend on the size and location of injury.

Subchondral infarcts often collapse and can lead to severe osteoarthritis.

Osteomyelitis

This refers to inflammation of the bone and related marrow cavity almost always due

to infection. Osteomyelitis can be acute or a chronic. The most common etiologic

agents are pyogenic bacteria and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Pyogenic Osteomyelitis

The offending organisms reach the bone by one of three routes:

1. Hematogenous dissemination (most common)

2. Extension from a nearby infection (in adjacent joint or soft tissue)

3. Traumatic implantation of bacteria (as after compound fractures or orthopedic

procedures).

Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequent cause. Mixed bacterial infections,

including anaerobes, are responsible for osteomyelitis complicating bone trauma. In

as many as 50% of cases, no organisms can be isolated.

Pathologic features:

The offending bacteria proliferate & induce an acute inflammatory reaction.

Entrapped bone undergoes early necrosis; the dead bone is called sequestrum.

The inflammation with its bacteria can permeate the Haversian systems to reach

the periosteum. In children, the periosteum is loosely attached to the cortex;

therefore, sizable subperiosteal abscesses can form and extend for long distances

along the bone surface.

Lifting of the periosteum further impairs the blood supply to the affected region,

and both suppurative and ischemic injury can cause segmental bone necrosis.

Rupture of the periosteum can lead to an abscess in the surrounding soft tissue and

eventually the formation of cutaneous draining sinus. Sometimes the sequestrum

crumbles and passes through the sinus tract.

In infants (uncommonly in adults), epiphyseal infection can spread into the

adjoining joint to produce suppurative arthritis, sometimes with extensive

destruction of the articular cartilage and permanent disability.

After the first week of infection chronic inflammatory cells become more

numerous. Leukocyte cytokine release stimulates osteoclastic bone resorption,

fibrous tissue ingrowth, and bone formation in the periphery, this occurs as a shell

of living tissue (involucrum) around a segment of dead bone. Viable organisms can

persist in the sequestrum for years after the original infection.

Chronicity may develop when there is delay in diagnosis, extensive bone necrosis,

and improper management.

Complications of chronic osteomyelitis include

1. A source of acute exacerbations

2. Pathologic fracture

3. Secondary amyloidosis

4. Endocarditis

5. Development of squamous cell carcinoma in the sinus tract (rarely osteosarcoma).

Tuberculous Osteomyelitis

Bone infection complicates up to 3% of those with pulmonary tuberculosis. Young

adults or children are usually affected. The organisms usually reach the bone

hematogenously. The long bones and vertebrae are favored sites. The lesions are

often solitary (multifocal in AIDS patients). The infection often spreads from the

initial site of bacterial deposition (the synovium of the vertebrae, hip, knee, ankle,

elbow, wrist, etc) into the adjacent epiphysis, where it causes typical granulomatous

inflammation with caseous necrosis and extensive bone destruction. Tuberculosis of

the vertebral bodies (Pott disease), is an important form of osteomyelitis. Infection at

this site causes vertebral deformity and collapse, with secondary neurologic deficits.

Extension of the infection to the adjacent soft tissues with the development of psoas

muscle abscesses is fairly common in Pott disease. Advanced cases are associated

with cutaneous sinuses, which cause secondary bacterial infections. Diagnosis is

established by synovial fluid direct examination, culture or PCR.

BONE TUMORS

Primary bone tumors are classified according to their normal cell of origin or line of

differentiation. Among the benign mass lesions, osteochondroma and fibrous cortical

defect occur most frequently. Osteosarcoma is the most common primary bone

cancer, followed by chondrosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. Benign tumors markedly

outnumber their malignant counterparts, particularly before age 40; bone tumors in

the elderly are much more likely to be malignant.

Most bone tumors develop during the first few decades of life and tend to originate in

the long bones of the extremities. Nevertheless, specific tumor types target certain age

groups and anatomic sites; such clinical information is often critical for the

appropriate diagnosis. For instance, most osteosarcomas occur during adolescence,

with half arising around the knee, either in the distal femur or proximal tibia. In

contrast, chondrosarcomas tend to develop during mid- to late adulthood and involve

the trunk, limb girdles, and proximal long bones.

Benign lesions are frequently asymptomatic and are detected as incidental findings.

Others produce pain or a slowly growing mass. Occasionally, a sudden pathologic

fracture is the first manifestation. Radiologic imaging is important in the evaluation of

bone tumors; however, biopsy and microscopic evaluations are necessary for the final

diagnosis.

Bone-Forming Tumors

1. Osteoma is a benign lesion of bone that in many cases represent a developmental

abnormaly or reactive growth rather than true neoplasms. They are most common in

the head, including the paranasal sinuses. Microscopically, there is a mixture of

woven and lamellar bone. They may cause local mechanical problems (e.g.,

obstruction of a sinus cavity) and cosmetic deformities.

2. Osteoid Osteoma and Osteoblastoma are benign neoplasms with very similar

histologic features. Both lesions typically arise during the 2

nd

& 3

rd

decades. They are

well-circumscribed lesions, usually involving the cortex. The central area of the

tumor, termed the nidus, is characteristically radiolucent. Osteoid osteomas arise most

often in the proximal femur and tibia, and are by definition less than 2 cm, whereas

osteoblastomas are larger. Localized pain is an almost universal complaint with

osteoid osteomas, and is usually relieved by aspirin. Osteoblastomas arise most often

in the vertebral column; they also cause pain, which is not responsive to aspirin.

Malignant transformation is rare unless the lesion is treated with radiation.

Gross features

Both lesions are round-to-oval masses of hemorrhagic gritty tan tissue.

A rim of sclerotic bone is present at the edge of both types of tumors.

Microscopic features

There are interlacing trabeculae of woven bone surrounded by osteoblasts.

The intervening connective tissue is loose, vascular & contains variable numbers

of giant cells.

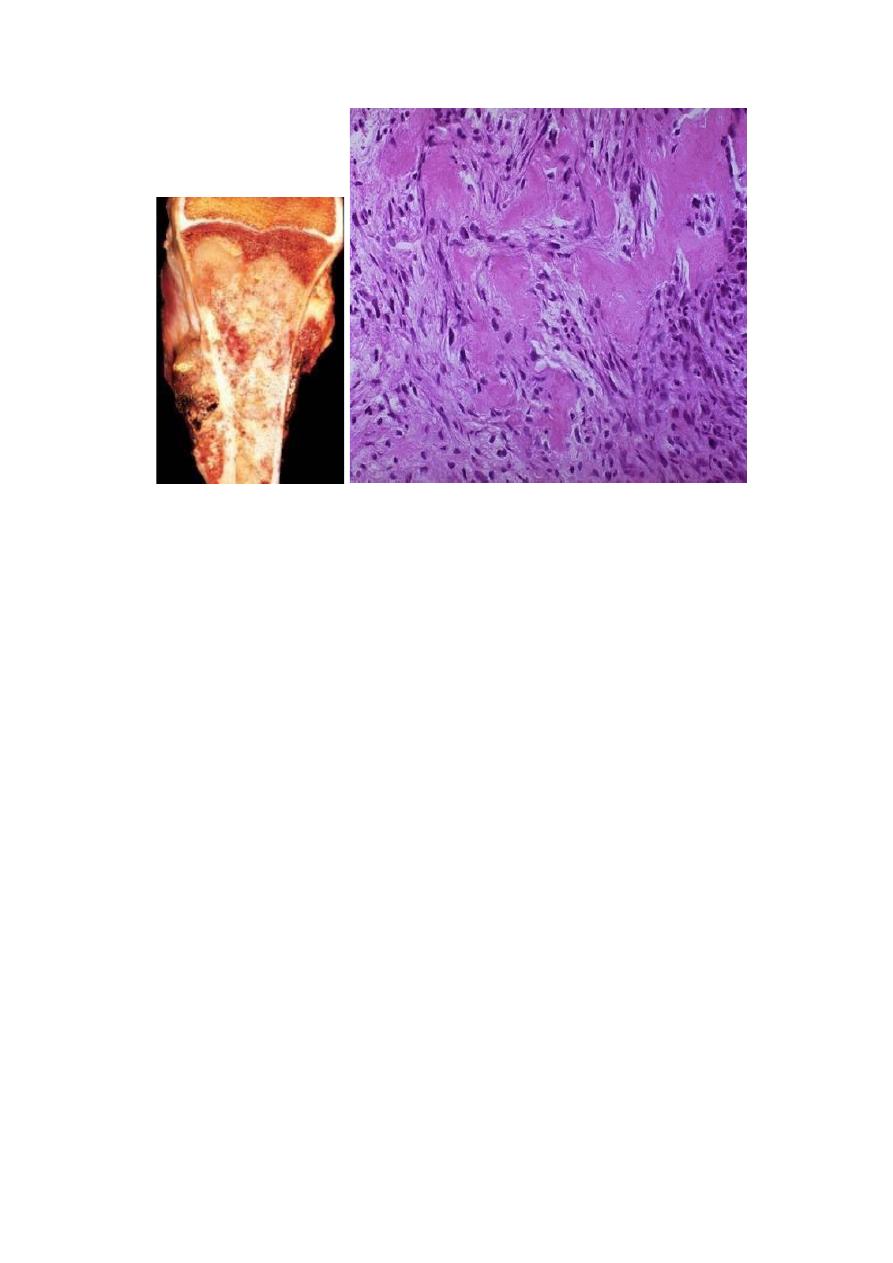

3. Osteosarcoma

This is “a bone-producing malignant mesenchymal tumor.” Excluding myeloma and

lymphoma, osteosarcoma is the most common primary malignant tumor of bone

(20%). The peak age of incidence is 10-25 years with 75% of the affected patients are

younger than age 20 years; there is a second peak that occurrs in the elderly, usually

secondary to other conditions, e.g. Paget disease, bone infarcts, and prior irradiation.

Most tumors arise in the metaphysis of the long bones of the extremities, with 60%

occurring about the knee, 15% around the hip, & 10% at the shoulder. The most

common type of osteosarcoma is primary, solitary, intramedullary, and poorly

differentiated, producing a predominantly bony matrix.

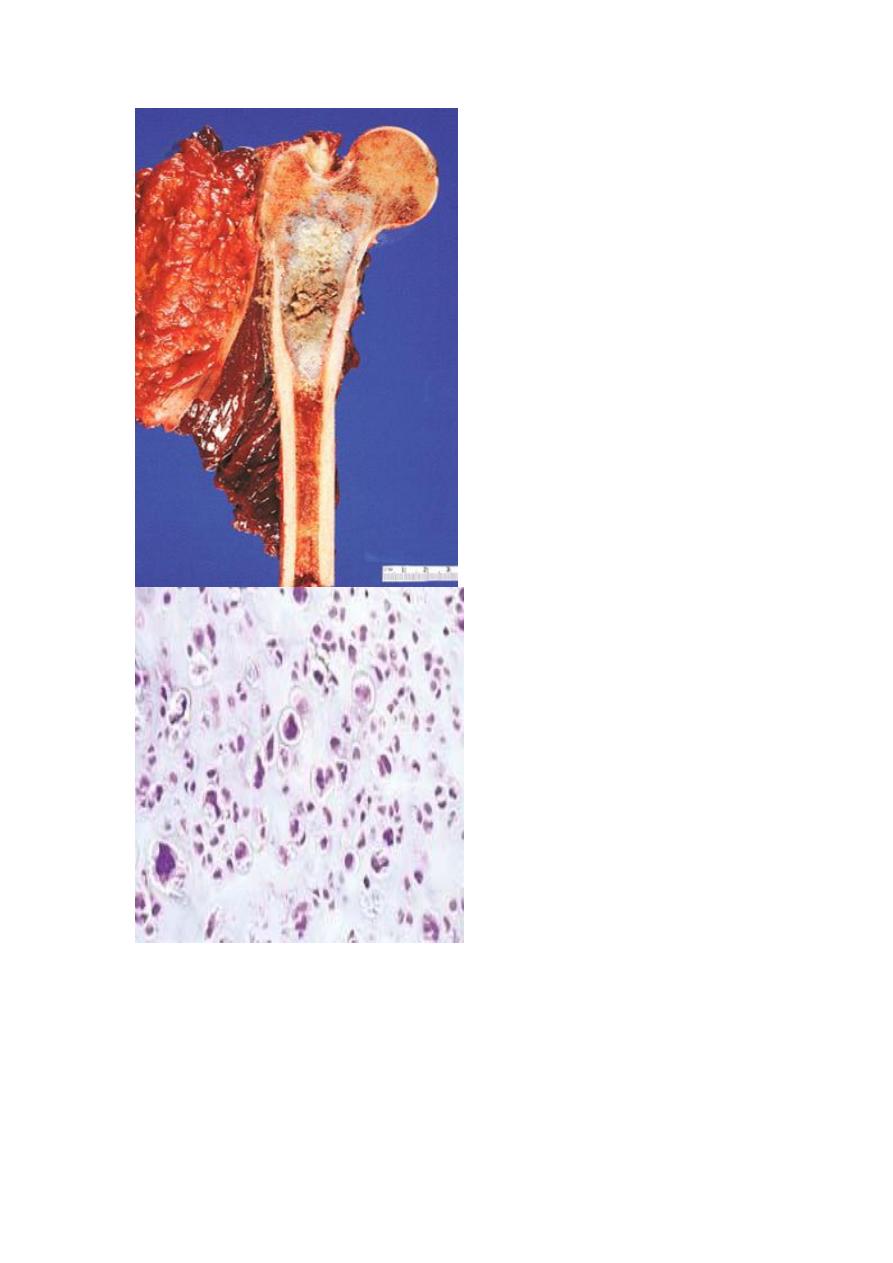

Gross features

The tumor is gritty, gray-white, often with foci of hemorrhage and cystic

degeneration.

It frequently destroys the surrounding cortex to extend into the soft tissue.

There is extensive spread within the medullary canal, with replacement of the

marrow. However, penetration of the epiphyseal plate or the joint space is

infrequent.

Microscopic features

Tumor cells are pleomorphic with large hyperchromatic nuclei; bizarre tumor giant

cells are common, as are mitoses.

The direct production of mineralized or unmineralized bone (osteoid) by malignant

cells is essential for diagnosis of osteosarcoma. The neoplastic bone is typically

fine, lace-like but can also be deposited in broad sheets.

Cartilage can be present in varying amounts. When malignant cartilage is

abundant, the tumor is called a chondroblastic osteosarcoma.

Pathogenesis

Several genetic mutations are closely associated with the development of

osteosarcoma. In particular, RB gene mutations that occur in both sporadic tumors,

and in individuals with hereditary retinoblastomas. In the latter there are germ-line

mutations in the RB gene (inherited).

Spontaneous osteosarcomas also frequently exhibit mutations in genes that regulate

the cell cycle including p53, cyclins, etc.

Osteosarcomas typically present as painful enlarging masses. Radiographs usually

show a large, destructive, mixed lytic and blastic mass with infiltrating margins. The

tumor frequently breaks the cortex and lifts the periosteum. The latter results in a

reactive periosteal bone formation; a triangular shadow on x-ray between the cortex

and raised periosteum (Codman triangle) is characteristic but not specific of

osteosarcomas. Osteosarcomas typically spread hematogenously; 10% to 20% of

patients have demonstrable pulmonary metastases at the time of diagnosis.

Cartilage-Forming Tumors

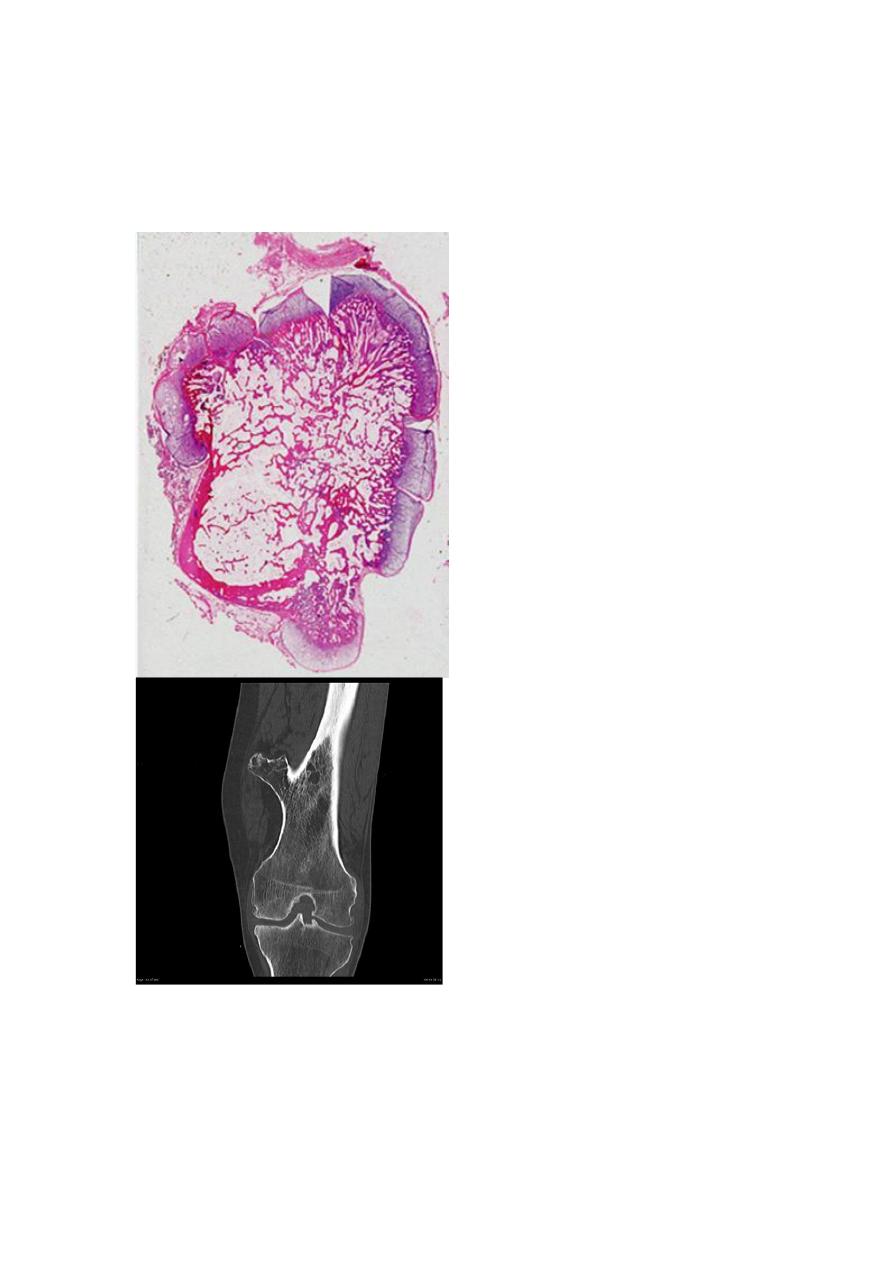

1. Osteochondroma (Exostosis) is a relatively common benign cartilage-capped

outgrowth attached by a bony stalk to the underlying skeleton. Solitary

osteochondromas are usually first diagnosed in late adolescence and early adulthood

(male-to-female ratio of 3:1); multiple osteochondromas become apparent during

childhood, occurring as multiple hereditary exostosis, an autosomal dominant

disorder. Inactivation of both copies of the EXT gene (a tumor suppressor gne) in

chondrocytes is implicated in both sporadic and hereditary osteochondromas.

Osteochondromas develop only in bones of endochondral origin arising at the

metaphysis near the growth plate of long tubular bones, especially about the knee.

They tend to stop growing once the normal growth of the skeleton is completed.

Occasionally they develop from flat bones (pelvis, scapula, and ribs). Rarely,

exostoses involve the short tubular bones of hands and feet.

Pathological features

Osteochondromas vary from 1-20cm in

size.

The cap is benign hyaline cartilage.

Newly formed bone forms the inner portion of the head and stalk, with the stalk

cortex merging with the cortex of the host bone.

Osteochondromas are slow-growing masses that may be painful. Osteochondromas

rarely progress to chondrosarcoma or other sarcoma, although patients with the

multiple hereditary exostoses are at increased risk of malignant transformation.

2. Chondroma is a benign tumor of hyaline cartilage. When it arises within the

medullary cavity, it is termed enchondroma; when on the bone surface it is called

juxtacortical chondroma. Enchondromas are usually diagnosed in persons between

ages 20 and 50 years; they are typically solitary and located in the metaphyseal region

of tubular bones, the favored sites being the short tubular bones of the hands and feet.

Ollier disease is characterized by multiple chondromas preferentially involving one

side of the body. Chondromas probably develop from slowly proliferating rests of

growth plate cartilage.

Pathological features

Enchondromas are gray-blue, translucent nodules usually smaller than 3 cm.

Microscopically, there is well-circumscribed hyaline matrix and cytologically

benign chondrocytes.

Most enchondromas are detected as incidental findings; occasionally they are painful

or cause pathologic fractures. Solitary chondromas rarely undergo malignant

transformation, but those associated with enchondromatosis are at increased risk.

3. Chondrosarcomas are malignant tumors of cartilage forming tissues. They are

divided into conventional chondrosarcomas and chondrosarcoma variants. Each of

these categories comprises several distinct types, some defined on microscopic

grounds & others on the basis of location within the affected bone, for e.g. they are

divided into central (medullary), peripheral (cortical), and juxtacortical (periosteal).

The common denominator of chondrosarcoma is the production of a cartilaginous

matrix and the lack of direct bone formation by the tumor cells (cf osteosarcoma).

Chondrosarcomas occur roughly half as frequently as osteosarcomas; most patients

age 40 years or more, with men affected twice as frequently as women.

Pathological features

Conventional chondrosarcomas arise within the medullary cavity of the bone to form

an expansile glistening mass that often erodes the cortex. They exhibit malignant

hyaline or myxoid stroma. Spotty calcifications are typically present. The tumor

grows with broad pushing fronts into marrow spaces and the surrounding soft tissue.

Tumor grade is determined by cellularity, cytologic atypia, and mitotic activity. Low-

grade tumors resemble normal cartilage. Higher grade lesions contain pleomorphic

chondrocytes with frequent mitotic figures with multinucleate cells and lacunae

containing two or more chondrocytes. Dedifferentiated chondrosarcomas refers to the

presence of a poorly differentiated sarcomatous component at the periphery of an

otherwise typical low-grade chondrosarcoma. Other histologic variants include

myxoid, clear-cell and mesenchymal chondrosarcomas. Chondrosarcomas commonly

arise in the pelvis, shoulder, and ribs. A slowly growing low-grade tumor causes

reactive thickening of the cortex, whereas a more aggressive high-grade neoplasm

destroys the cortex and forms a soft tissue mass. There is also a direct correlation

between grade and biologic behavior. Size is another prognostic feature, with tumors

larger than 10 cm being significantly more aggressive than smaller tumors. High-

grade Chondrosarcomas metastasize hematogenously, preferentially to the lungs and

skeleton.

Fibrous and Fibro-Osseous Tumors

Fibrous tumors of bone are common and comprise several morphological variants.

1. Fibrous Cortical Defect and Nonossifying Fibroma

Fibrous cortical defects occur in 30% to 50% of all children older than 2 years of

age; they are probably developmental rather than true neoplasms. The vast majority

are smaller than 0.5 cm and arise in the metaphysis of the distal femur or proximal

tibia; almost half are bilateral or multiple. They may enlarge in size (5-6 cm) to form

nonossifying fibromas. Both lesions present as sharply demarcated radiolucencies

surrounded by a thin zone of sclerosis. Microscopically are cellular and composed of

benign fibroblasts and macrophages, including multinucleated forms. The fibroblasts

classically exhibit a storiform pattern. Fibrous cortical defects are asymptomatic and

are usually only detected as incidental radiographic lesions. Most undergo

spontaneous differentiation into normal cortical bone. The few that enlarge into

nonossifying fibromas can present with pathologic fracture; in such cases biopsy is

necessary to rule out other tumors.

2. Fibrous Dysplasia is a benign mass lesion in which all components of normal bone

are present, but they fail to differentiate into mature structures. Fibrous dysplasia

occurs as one of three clinical patterns:

A. Involvement of a single bone (monostotic)

B. nvolvement of multiple bones (polyostotic)

C. Polyostotic disease, associated with café au lait skin pigmentations and endocrine

abnormalities, especially precocious puberty (Albright syndrome).

Fibrous dysplasia can be :

Monostotic fibrous dysplasia accounts for 70% of cases

Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia without endocrine dysfunction accounts for the

majority of the remaining cases.

Albright syndrome accounts for 3% of all cases.

Gross features

The lesion is well-circumscribed, intramedullary; large masses expand and distort

the bone.

On section it is tan-white and gritty.

Microscopic features

There are curved trabeculae of woven bone (mimicking Chinese characters),

without osteoblastic rimming

The above are set within fibroblastic proliferation

Rarely, polyostotic disease can transform into osteosarcoma, especially following

radiotherapy.

Other Bone Tumors

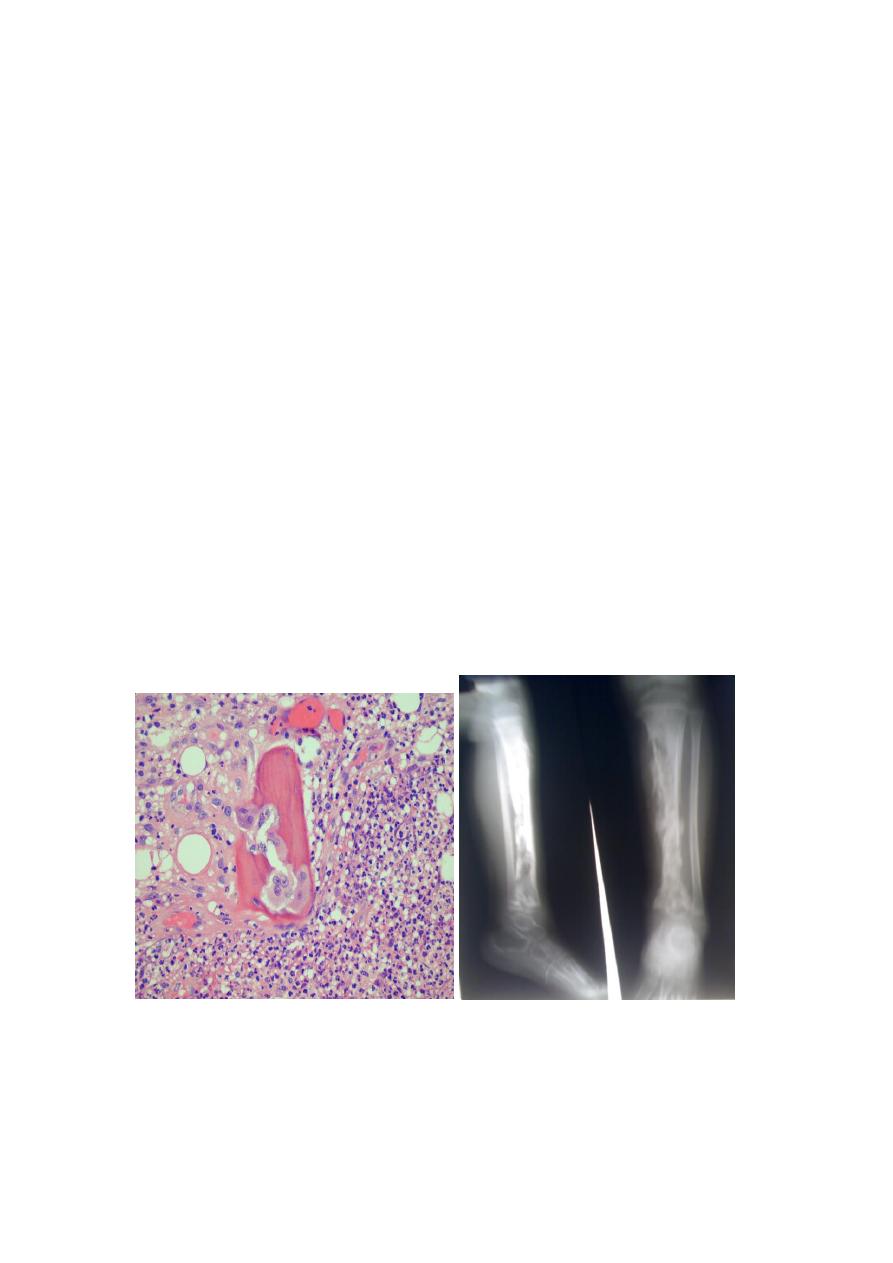

1. Ewing Sarcoma & Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor (PNET) are primary

malignant small round-cell tumors of bone and soft tissue. They are viewed as the

same tumor because they share an identical chromosome translocation; they differ

only in degree of differentiation. PNETs demonstrate neural differentiation whereas

Ewing sarcomas are undifferentiated. After osteosarcomas, they are the second most

common pediatric bone sarcomas. Most patients are 10 to 15 years old. The common

chromosomal abnormality is a translocation that causes fusion of the EWS gene with a

member of the ETS family of transcription factors. The resulting hybrid protein

functions as an active transcription factor to stimulate cell proliferation. These

translocations are of diagnostic importance since almost all patients with Ewing

tumor have t(11;22).

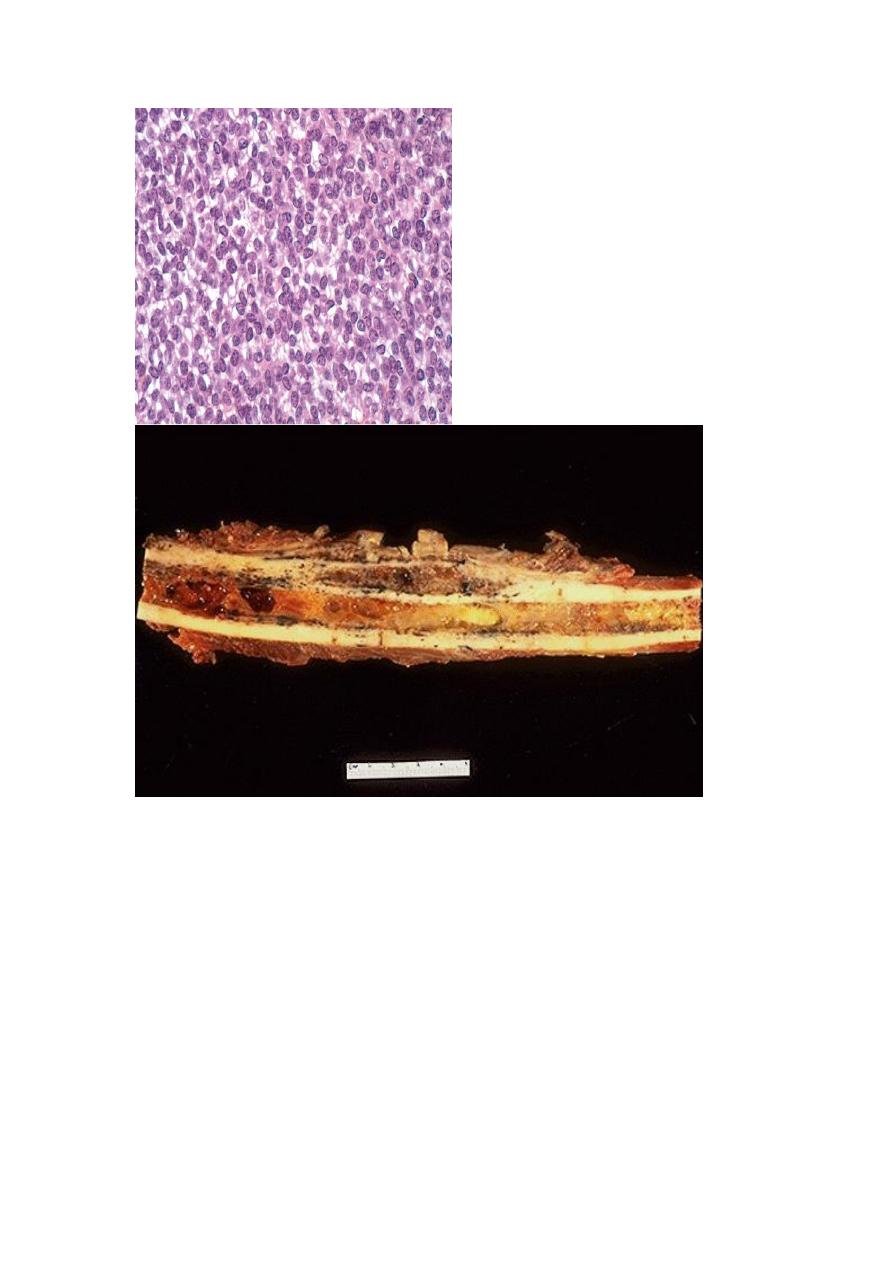

Pathological features

Ewing sarcoma and PNETs arise in the medullary cavity but eventually invade the

cortex and periosteum to produce a soft tissue mass.

The tumor is tan-white, frequently with foci of hemorrhage and necrosis.

Microscopic features

There are sheets of uniform small, round cells that are slightly larger than

lymphocytes with few mitoses and little intervening stroma.

The cells have scant glycogen-rich cytoplasm.

The presence of Homer-Wright rosettes (tumor cells circled about a central

fibrillary space) indicates neural differentiation, and hence indicates by definition

PNET.

Ewing sarcoma and PNETs typically present as painful enlarging masses in the

diaphyses of long tubular bones (especially the femur) and the pelvic flat bones. The

tumor may be confused with osteomyelitis because of its association with systemic

signs & symptoms of infection. X-rays show a destructive lytic tumor with infiltrative

margins and extension into surrounding soft tissues. There is a characteristic

periosteal reaction depositing bone in an onionskin fashion.

1. Giant-Cell Tumor of Bone (GCT):

is dominated by multinucleated osteoclast-type giant cells, hence the

synonym osteoclastoma. GCT is benign but locally aggressive, usually arising

in individuals in their 20s to 40s. Current opinion suggests that the giant cell

component is likely a reactive macrophage population and the mononuclear

cells are neoplastic. Tumors are large and red-brown with frequent cystic

degeneration. They are composed of uniform oval mononuclear cells with

frequent mitoses, with scattered osteoclast-type giant cells that may contain 30

or more nuclei.

The majority of GCTs arise in the epiphysis of long bones around the knee (distal

femur and proximal tibia). Radiographically, GCTs are large, purely lytic, and

eccentric; the overlying cortex is frequently destroyed, producing a bulging soft tissue

mass with a thin shell of reactive bone. Although GCTs are benign, roughly 50%

recur after simple curettage; some malignant examples (5%) metastasize to the lungs.