1

Third stage

Medicine

Lec-4

د

.

اسماعيل

1/1/2014

MALARIA

(Blood protozoal disease)

Causes:

Plasmodium falciparum

Plasmodium vivax

Plasmodium malariae

Plasmodium ovale

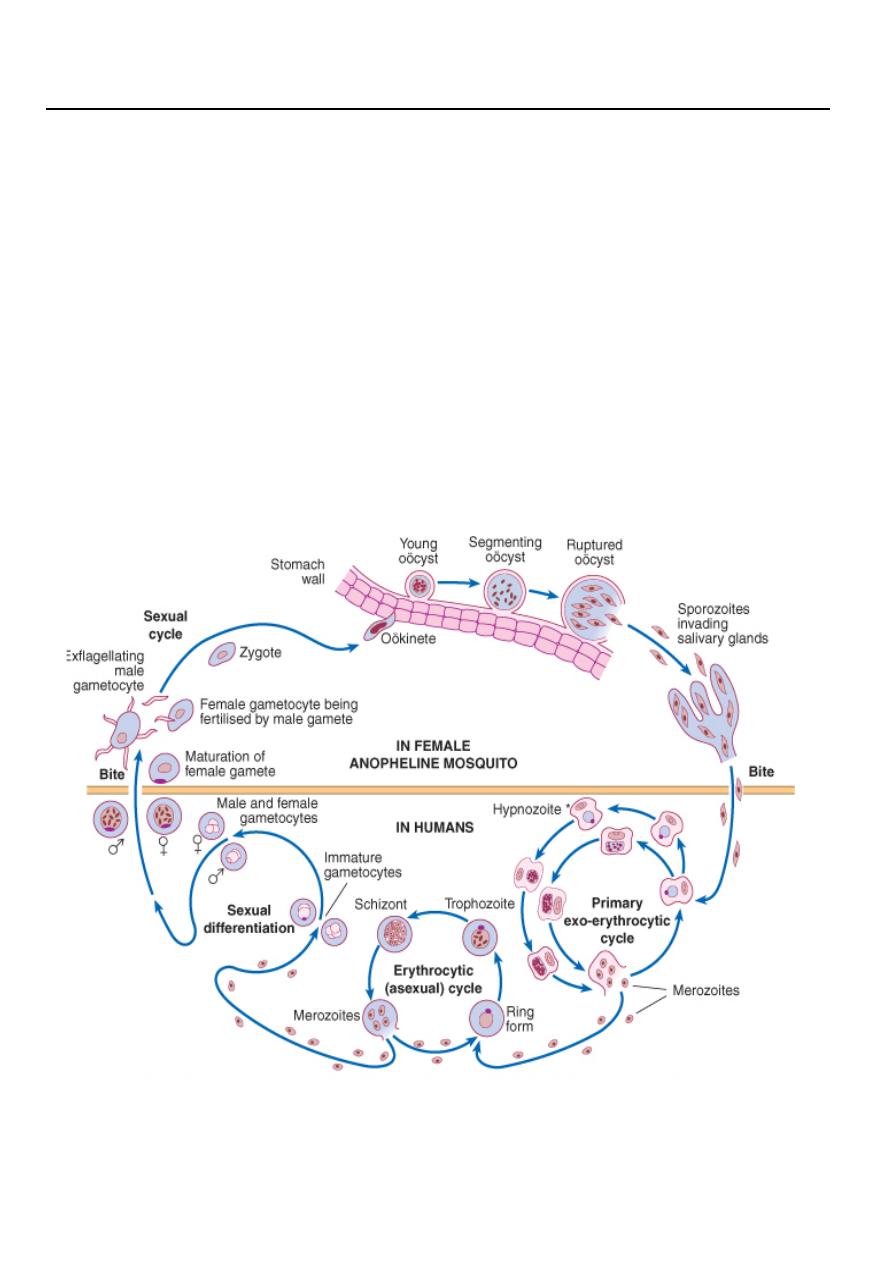

Life cycle:

2

P. falciparum and P. malariae have no persistent exoerythrocytic phase but

recrudescences of fever may result from multiplication in the red cells of parasites

which have not been eliminated by treatment and immune processes

Transmission:

1. It is transmitted by the bite of female anopheline mosquitoes and occurs

throughout the tropics and subtropics.

2. Blood transmission and by injection.

3. trans-placenta

Effects on red blood cells and capillaries

1. haemolysis of infected red cells and adherence of infected red blood cells to

capillaries. Malaria is always accompanied by haemolysis and in a severe or

prolonged attack anaemia may be profound. Anaemia is worsened by

dyserythropoiesis, splenomegaly and depletion of folate stores. Haemolysis is most

severe with P. falciparum, which invades red cells of all ages but especially young

cells. P. vivax and P. ovale invade reticulocytes, and P. malariae normoblasts, so

that infections remain lighter.

P. falciparum does not grow well in red cells that contain haemoglobin F, C or

especially S. Haemoglobin S heterozygotes (AS) are protected against the lethal

complications of malaria. P. vivax cannot enter red cells that lack the Duffy blood

group. West Africans and African-Americans are protected.

2. In P. falciparum malaria, red cells containing schizonts adhere to capillary

endothelium in brain, kidney, liver, lungs and gut. The vessels become congested

and the organs anoxic.

3. haemolysis of infected red cells and adherence of infected red blood cells to

capillaries. Malaria is always accompanied by haemolysis and in a severe or

prolonged attack anaemia may be profound. Anaemia is worsened by

dyserythropoiesis, splenomegaly and depletion of folate stores. Haemolysis is most

severe with P. falciparum, which invades red cells of all ages but especially young

cells. P. vivax and P. ovale invade reticulocytes, and P. malariae normoblasts, so

that infections remain lighter.

Clinical manifestation of P. vivax and Ovale

In many cases the illness starts with several days of continued fever before the

development of classical bouts of fever on alternate days. Fever starts with a rigor.

The patient feels cold and the temperature rises to about 40°C. After half an hour to

3

an hour the hot or flush phase begins. It lasts several hours and gives way to

profuse perspiration and a gradual fall in temperature. The cycle is repeated 48

hours later. Gradually the spleen and liver enlarge and may become tender.

Anaemia develops slowly. Herpes simplex is common. Relapses are frequent in the

first 2 years after leaving the malarious area.

Clinical manifestation of Falciparum malaria:

• This is the most dangerous of the malarias. The onset is often insidious, with

malaise, headache and vomiting, and is often mistaken for influenza. Cough

and mild diarrhoea are also common. The fever has no particular pattern.

Jaundice is common due to haemolysis and hepatic dysfunction. The liver and

spleen enlarge and become tender. Anaemia develops rapidly.

• A patient with falciparum malaria, apparently not seriously ill, may develop

dangerous complications. Cerebral malaria is the most serious complication

and is manifested by either confusion or coma, usually without localising

signs. Children die rapidly without any special symptoms other than fever.

Immunity is impaired in pregnancy, and abortion from parasitisation of the

maternal side of the placenta is frequent. Splenectomy increases the risk of

severe malaria.

Complications of severe F. malaria:

1. Coma (cerebral malaria)

2. Hyperpyrexia

3. Convulsions

4. Hypoglycaemia

5. Severe anaemia

6. Acute pulmonary oedema

7. Acute renal failure

8. Spontaneous bleeding and coagulopathy

9. Metabolic acidosis

10. Shock ('algid malaria')

11. Aspiration pneumonia

12. Hyperparasitaemia (e.g. > 10% of circulating erythrocytes parasitised in non-

immune patient with severe disease)

4

Clinical manifestation of Malaria due to P. malariae:

This is usually associated with mild symptoms and bouts of fever every third day.

Parasitaemia may persist for many years with the occasiolnal recrudescence of

fever, or without producing any symptoms. P. malariae causes glomerulonephritis

and the nephrotic syndrome in children.

Diagnosis:

1. Thick and thin blood films should be taken whenever malaria is suspected.

Thick film:

A. all blood stages of the parasite released.

B. more blood is used in thick films,

Both help in the diagnosis of low-level parasitaemias.

Thin film:

A. is essential to confirm the diagnosis,

B. to identify the species of parasite and,

C. in P. falciparum infections, to quantify the parasite load (by counting the

percentage of infected erythrocytes).

In P. falciparum parasites may be very scanty, especially in patients who have been

partially treated. With P. falciparum, only ring forms are normally seen in the early

stages. With the other species all stages of the erythrocytic cycle may be found.

Gametocytes appear after about 2 weeks. They persist after treatment and are

harmless, but are the source for infecting mosquitoes.

2. Immunochromatographic 'dipstick' tests for P. falciparum antigen are now

marketed and provide a useful non-microscopic means of diagnosing this infection.

They should be used in parallel with blood film examination but are about 100 times

less sensitive than a carefully examined blood film.

Treatment of P. vivax, P. ovale and P. malariae

P. vivax, P. ovale and P. malariae infections should be treated with chloroquine: 600

mg chloroquine base followed by 300 mg base in 6 hours, then 150 mg base 12-

hourly for 2 more days.

• P. falciparum is now resistant to chloroquine almost world-wide, so quinine is

the drug of choice. Quinine dihydrochloride or sulphate 600 mg salt (10 mg/kg)

8-hourly by mouth is given until the patient is clinically better and the blood is

5

free of parasites (usually 3-5 days). The dose should be reduced to 12-hourly

intervals if quinine toxicity develops. This regimen should be followed by a

single dose of sulfadoxine 1.5 g combined with pyrimethamine 75 mg, i.e. 3

tablets of Fansidar. In pregnancy a 7-day course of quinine alone should be

given.

• If sulphonamide sensitivity is suspected, quinine may be followed by

doxycycline 100 mg daily for 7 days..

• Mefloquine: Also may be used but may cause alarming neuropsychiatric side-

effects which can persist for several days due to its plasma half-life of 14 days.

Radical cure of malaria due to P. vivax and P. ovale

Relapses can be prevented by taking one of the antimalarial drugs in suppressive

doses.

Radical cure is achieved in most patients with a course of primaquine (15 mg daily

for 14 days), which destroys the hypnozoite phase in the liver. Haemolysis may

develop in those who are glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD)-deficient.

Cyanosis due to the formation of methaemoglobin in the red cells is more common

but not dangerous.

Prevention

1. Avoiding mosquito bites:

A. Long sleeves and trousers

B. Repellent creams and sprays

C. Screened windows

D. the use of a mosquito net

2. Chemoprophylaxis

A. Clinical attacks of malaria may be preventable with drugs such as proguanil 1

– 2

tablets daily, which attack the pre-erythrocytic form,

B. and also by drugs such as chloroquine (4-aminoquinolones) 2 tablets weekly after

the parasite has entered the erythrocyte ('suppression')

Start 1 W before entering and 4 Ws after leaving the endemic area.