1

Third stage

Medicine

Lec-8

د

.

اسماعيل

1/1/2014

SCHISTOSOMIASIS (BILHARIZIASIS)

Is a human disease syndrome due to infestation by Schistosoma. Most human

schistosomiasis is caused by:

1. Schistosoma haematobium discovered by Theodor Bilharz in Cairo in 1861 (mainly UTS).

2. Schistosoma mansoni (mainly GIT).

3. Schistosoma japonicum (mainly GIT).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Schistosomiasis is a major source of morbidity and mortality. The endemic areas are limited

to tropical and subtropical zones, which exist around the world. The spread continues

because of

A. Water resource contamination in developing countries

B. The migration of infected populations.

At least 200 million people in at least 74 countries have active schistosomal infection. Of

these, approximately 120 million people have symptoms, and 20 million are severely ill.

Disease prevalence tends to be worse in areas with poor sanitation, increased freshwater

irrigation usage, and heavy schistosomal infestation of human and/or snail populations.

S mansoni and S haematobium infections predominate in sub-Saharan Africa.

S mansoni is endemic in parts of South America and the Caribbean.

S japonicum is common in China, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

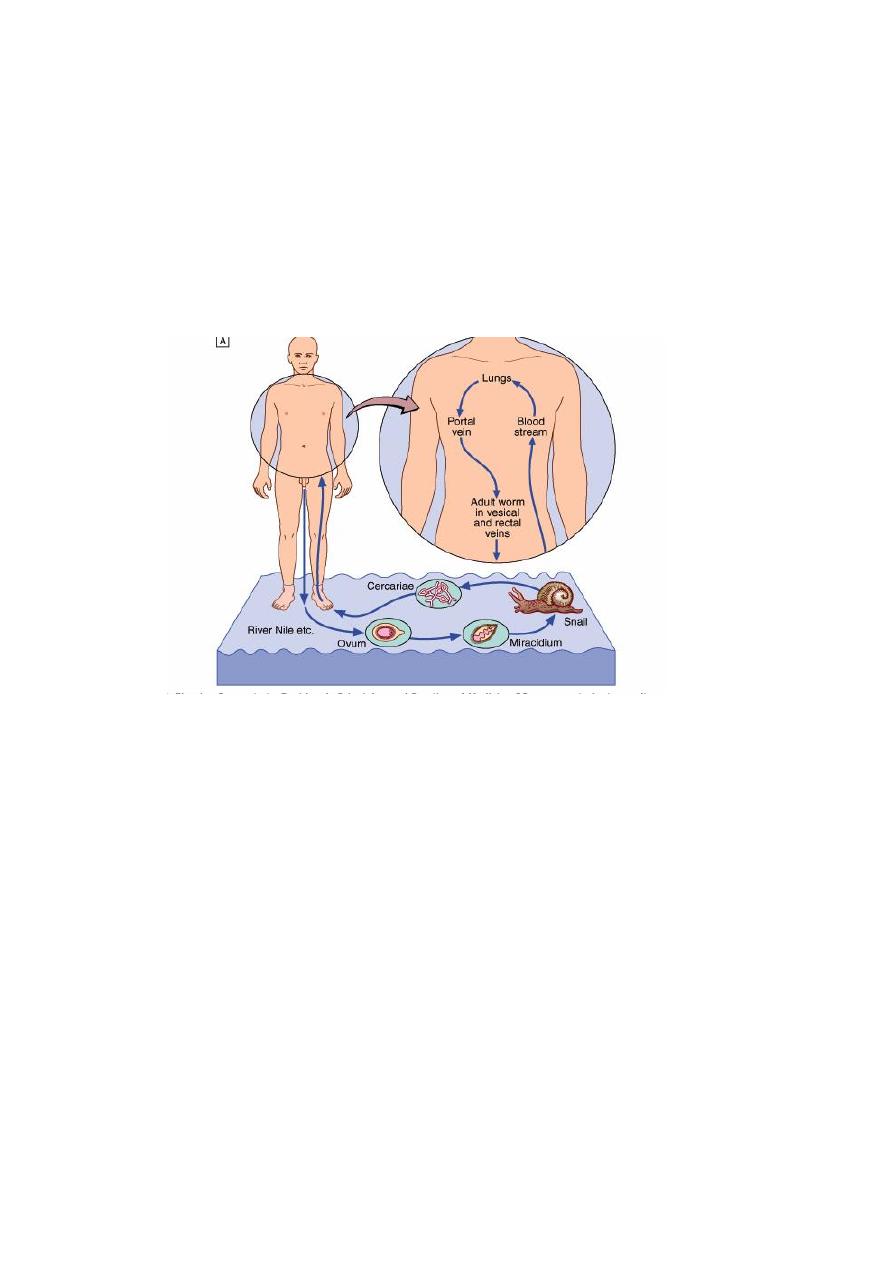

LIFE CYCLE

The ovum is passed in the urine or faeces of infected individuals and gains access to fresh

water where the ciliated miracidium inside it is liberated; it enters its intermediate host, a

species of freshwater snail, in which it multiplies.

Large numbers of fork-tailed cercariae are then liberated into the water, where they may

survive for 2-3 days.

2

Cercariae can penetrate the skin or the mucous membrane of the mouth of their definitive

host, humans. They transform into schistosomulae and moult as they pass through the

lungs and are carried by the blood stream to the liver and so to the portal vein where they

mature.

The male worm is up to 20 mm in length and the more slender cylindrical female, usually

enfolded longitudinally by the male, is rather longer. Within 4-6 weeks of infection they

migrate to the venules draining the pelvic viscera, where the females deposit ova.

Life cycle:

PATHOLOGY

The pathological changes and symptoms depend on species and stage of infection. Most of

the disease is due to the passage of eggs through mucosa and to the granulomatous

reaction to eggs deposited in tissues. The eggs of S. haematobium pass mainly through the

wall of the bladder, but may also involve rectum, seminal vesicles, vagina, cervix and

uterine tubes.

• S. mansoni and S. japonicum eggs pass mainly through the wall of the lower bowel or

are carried to the liver.

• The most serious, although rare, consequences of the ectopic deposition of eggs are

transverse myelitis and paraplegia.

• Granulomas are composed of macrophages, eosinophils, epithelioid and giant cells

around an ovum.

Later there is fibrosis and eggs calcify, often in sufficient numbers to become radiologically

visible. Eggs of S. haematobium, and of the other two species after the development of

portal hypertension, may reach the lungs.

3

CLINICAL MANIFESTATION:

1. URINARY TRACT 2. GIT AND LIVER 3.GENITAL TRACT 4. PULMONARY HYPERTENTION

5. SPINAL CORD

A. Acute schistosomiasis (Katayama fever)

During the early stages of infection there may be itching lasting 1-2 days at the site of

cercarial penetration. After a symptom-free period of 3-5 weeks, acute schistosomiasis

(Katayama syndrome) may present with allergic manifestations such as urticaria, fever,

muscle aches, abdominal pain, headaches, cough and sweating.

On examination: Hepatomegaly, splenomegaly,lymphadenopathy and pneumonia may be

present. There is eosinophilia and schistosomiasis serology maybe positive. These allergic

phenomena may be severe in infections with S. mansoni and S. japonicum but are rare with

S. haematobium. The features subside after 1-2 weeks.

B. Chronic schistosomiasis

The manifestation is due to egg deposition and occurs months to years after infection. The

symptoms and signs depend upon the intensity of infection and the species of infecting

schistosome.

S. haematobium

Humans are the only natural hosts of S. haematobium, which is highly endemic in Egypt and

East Africa, and occurs throughout Africa and the Middle East . Infection can be acquired

after a brief exposure such as swimming in freshwater

lakes in Africa.

• Painless terminal haematuria is usually the first and most common symptom.

• Frequency of micturition follows, due to bladder neck obstruction.

• Later the disease may be complicated by frequent urinary tract infections, bladder or

ureteric stone formation, hydronephrosis, renal functional abnormalities

• and ultimately renal failure with a contracted calcified bladder.

• Pain in the iliac fossa or in the loin and radiates to the groin.

• association of S. haematobium infection with squamous cell carcinoma of the

bladder.

• Disease of the seminal vesicles may lead to haemospermia. Females may develop

schistosomal papillomas of the vulva, and schistosomal lesions of the cervix may be

mistaken for cancer. Intestinal symptoms may follow involvement of the bowel wall.

• Ectopic worms cause skin or cord lesions.

4

• The severity of S. haematobium infection varies greatly, and many with a light

infection are asymptomatic. However, as adult worms can live for 20 years or more

and lesions may progress, these patients should always be treated.

LIVER AND GIT INVOLVEMENT (Mainly S. Mansoni and Japanicum)

– Bloody diarrhea

– Abdominal pain: RUQ pain, cramping

– Hematemesis (with portal hypertension)

– Ascites (with portal hypertension)

– Vulvar or perianal lesions

– On examination: Hepatosplenomegaly

– Abdominal tenderness

– Heme-positive stool and/or bloody diarrhea

– Ascites

Note: Hepatic failure and jaundice are not features of hepatic schistosomiasis

OTHER SITES AFFECTED BY SCHISTOSOMIASIS

Pulmonary hypertension

– Dyspnea on exertion .

– Cough .

– Palpitations .

– Atypical chest pain .

– Pedal edema (with right heart failure)

Central nervous system (CNS)

– Seizures and/or mental status changes (with cerebral involvement)

– Paralysis (with spinal cord involvement).

– Skin involvement.

DIAGNOSIS

1. CLINICAL

2. HEMATOLOGICAL, BIOCHEMICAL

3. CONFIRMED BY Detection of ova in urine deposit of terminal stream (especially after

exercise) or from stool, biopsy or snip from rectum and bladder wall. Ovum has

terminal spine in S. Hematobium and lateral spine in S. mansoni Serological tests

ELISA for screening

4. Radiological and scope examination

5

SPECIFIC TREATMENT

The aim is to stop egg-laying and reduce adult worm load up to 90%

• Praziquantel 40mg /kg for all types and as a single dose. Induce parasitological cure in

80% of people and over 90% reduction in egg count in the remaining individuals. Side

effects like nausea and abdominal pain are uncommon. Early therapy reverse

pathological changes like hepatomegaly and bladder wall thickening and even large

granuloma .

Surgery in special circumstances and for some complications like ureteric stricture, and

small fibrotic urinary bladder. Diathermy for rectal papiloma removal. Neurosurgical

procedures may be needed for neurological complications if chemotherapy is

ineffective.

COMPLICATIONS OF SCHISTOSOMAISIS IN GENERAL:

1. Pulmonary hypertension

2. Cor pulmonale

3. Portal hypertension.

4. Obstructive uropathy.

5. Squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder.

6. Gastrointestinal bleeding

7. Carrier for salmonella

8. Neurological complications

Prognosis

• Almost all patients improve with treatment.

• Most patients with early disease or without severe end-organ

• Surprisingly, patients with hepatic and urinary disease, even with fibrosis, may

improve significantly over months or years following treatment.

• Resolution of pulmonary disease is less well documented.

Patients with heavier worm burdens are less likely to improve and are more likely to

require re-treatment.

Treatment is indicated for patients with end-stage complications of portal hypertension and

severe pulmonary hypertension, but these patients are much less likely to benefit

Co-infection (with malaria, HIV, or hepatitis worsens the prognosis.

6

PREVENTION

Travelers to endemic areas should avoid exposure to freshwater that is likely to be

contaminated.

No accepted prophylactic regimens have been developed.

No vaccines are currently available, although vaccine development is increasingly

promising.

Early treatment after high-risk exposures should minimize morbidity.

Prevention for groups residing in endemic areas is more difficult than prevention for

travelers.

Improved sanitation to decrease freshwater contamination with sewage should decrease

disease prevalence.

Decrease occupational and recreational contact with contaminated water may be useful.

These interventions are particularly problematic with children.

Molluscicides to decrease the prevalence of the snail hosts have some usefulness but

require frequent reapplication and are used less frequently now than in the past.

Mass treatment of targeted populations with the newer less toxic antischistosomal agents

may have utility. It can be combined with molluscicide treatment if needed.

Vaccines hold the promise of significantly reducing infection in endemic areas