1

Third stage

Medicine

Lec-1

د

.

عالء

نصوح

1/1/2014

Spirochetal Infections

General Overview of Spirochetes

Gram-negative microorganisms.

Spirochete from Greek for “coiled hair”

Extremely thin and can be very long

Tightly coiled helical cells with tapered ends

Motile by periplasmic flagella

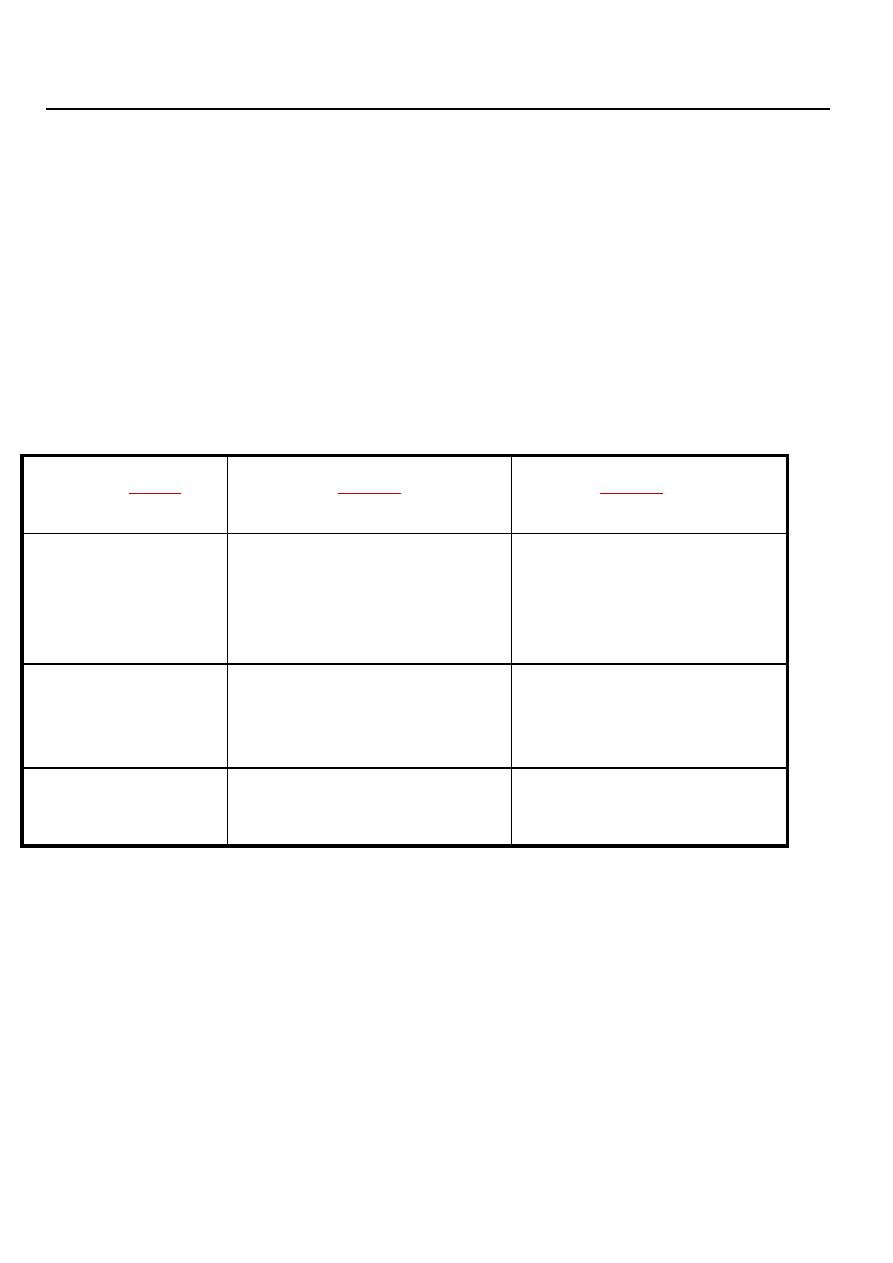

Spirochetes Associated Human Diseases

Genus

Species

Disease

Treponema

pallidum ssp. pallidum

pallidum ssp. endemicum

pallidum ssp. pertenue

carateum

Syphilis

Bejel

Yaws

Pinta

Borrelia

burgdorferi

recurrentis

Many species

Lyme disease (borreliosis)

Epidemic relapsing fever

Endemic relapsing fever

Leptospira

interrogans

Leptospirosis

(Weil’s Disease)

Endemic treponematoses:

Yaws :

Yaws is a granulomatous disease, mainly involving the skin and bones, morphologically and

serologically indistinguishable from the causative organisms of syphilis and pinta. It is

important to establish the geographical origin and sexual history of patients to exclude a

false-positive syphilis serology due to the endemic treponemal infections. WHO eradicated

yaws from many areas, but the disease has persisted patchily throughout the tropics.

Organisms are transmitted by bodily contact from a patient with infectious yaws through

minor abrasions of the skin of another patient, usually a child. After an incubation period of

3-4 weeks, a proliferative granuloma containing numerous treponemes develops at the site of

2

inoculation. This primary lesion is followed by secondary eruptions. In addition, there may

be hypertrophic periosteal lesions of many bones, with underlying cortical rarefaction.

Lesions of late yaws are characterised by destructive changes which closely resemble the

osteitis and gummas of tertiary syphilis and which heal with much scarring and deformity.

Pinta and bejel

These two treponemal infections occur in poor rural populations with low standards of

domestic hygiene, but are found in separate parts of the world. They have features in

common, notably that they are transmitted by contact, usually within the family and not

sexually, and in the case of bejel, through common eating and drinking utensils.

Pinta. Pinta is probably the oldest of the human treponemal infections. It is found only in South and

Central America, where its incidence is declining. The infection is confined to the skin. The early

lesions are scaly papules or dyschromic patches on the skin. The late lesions are often depigmented

and disfiguring.

Bejel. Bejel is the Middle Eastern name for non-venereal syphilis, which has a patchy

distribution across sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia and Australia. It

has been eradicated from Eastern Europe. Transmission is most commonly from the

mouth of the mother or child and the primary mucosal lesion is seldom seen. The early

and late lesions resemble those of secondary and tertiary syphilis but cardiovascular

and neurological disease are rare.

Diagnosis and treatment of yaws, pinta and bejel

Diagnosis of early stages

Detection of spirochaetes in exudate of lesions by dark ground

microscopy

Diagnosis of latent and early stages

Positive serological tests, as for syphilis

Treatment of all stages

Single intramuscular injection of 1.2 g long-acting (e.g. benzathine)

benzylpenicillin

Borrelia infections

:

Borrelia are flagellated spirochaetal bacteria which infect humans after bites from

ticks or lice. They cause a variety of human infections world-wide .

Lyme disease :

The reservoir of infection is ixodid (hard) ticks that feed on a variety of large

mammals, particularly deer. Birds may spread ticks over a wide area. The organism is

transmitted to humans via the bite of infected ticks.

Clinical features

There are three stages of disease. Progression may be arrested at any stage.

Early localised disease: The characteristic feature is a skin reaction around the site of

3

the tick bite, known as erythema migrans . Initially, a red 'bull's eye' macule or papule

appears 2-30 days after the bite. It then enlarges peripherally with central clearing, and

may persist for months. The lesion is not pathognomonic of Lyme disease since

similar lesions can occur after tick bites in areas where Lyme disease does not occur.

Other acute manifestations such as fever, headache and regional lymphadenopathy

may develop with or without the rash.

Early disseminated disease: Dissemination occurs via the blood stream and

lymphatics. There may be a systemic reaction with malaise, arthralgia, and

occasionally metastatic areas of erythema migrans . Neurological involvement may

follow weeks or months after infection. Common features include lymphocytic

meningitis, cranial nerve palsies (especially unilateral or bilateral facial nerve palsy)

and peripheral neuropathy. Radiculopathy, often painful, may present a year or more

after initial infection. Carditis, sometimes accompanied by atrioventricular conduction

defects also can occure.

Late disease: Late manifestations include arthritis, polyneuritis and encephalopathy.

Prolonged arthritis, particularly affecting large joints, and brain parenchymal

involvement causing neuropsychiatric abnormalities may occur.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of early Lyme borreliosis is often clinical. Culture from biopsy material is not

generally available, has a low yield, and may take longer than 6 weeks. Antibody detection is

frequently negative early in the course of the disease, but sensitivity increases to 90-100% in

disseminated or late disease. Immunoblot (Western blot) techniques are more specific and,

although technically demanding, should be used to confirm the diagnosis. Microorganism

DNA detection by PCR has been applied to blood, urine, CSF, and biopsies of skin and

synovium.

Management

Recent evidence suggests that asymptomatic patients with positive antibody tests should not

be treated. However, erythema migrans always requires therapy because organisms may

persist and cause progressive disease, even if the skin lesions resolve. Standard therapy

consists of a 14-day course of doxycycline (200 mg daily) or amoxicillin (500 mg 8-hourly).

In pregnant women and small children, or in those allergic to amoxicillin and doxycycline,

14-day treatment with cefuroxime axetil (500 mg 12-hourly) or erythromycin (250 mg 6-

hourly) may be used.

Disseminated disease and arthritis require therapy for a minimum of 28 days..

Neuroborreliosis is treated with parenteral β-lactam antibiotics for 3-4 weeks; the

cephalosporins may be superior to penicillin in this situation.

Prevention

Protective clothing and insect repellents should be used in tick-infested areas. Since the risk

of borrelial transmission is lower in the first few hours of a blood feed, prompt removal of

ticks is advisable. Where risk of transmission is high, a single 200 mg dose of doxycycline,

given within 72 hours of exposure, has been shown to prevent erythema migrans.

4

Louse-borne relapsing fever

The human body louse, Pediculus humanus, causes itching. Borreliae (B. recurrentis) are

liberated from the infected lice when they are crushed during scratching, which also

inoculates the borreliae into the skin. The disease occurs world-wide, with epidemic

relapsing fever most often seen in Central and East Africa, and in South America.

The borreliae multiply in the blood, where they are abundant in the febrile phases, and

invade most tissues, especially the liver, spleen and meninges. Hepatitis and

thrombocytopenia are common.

Clinical features

Onset is sudden with fever. The temperature rises to 39.5-40.5°C, accompanied by a

tachycardia, headache, generalised aching, injected conjunctivae and, frequently, a petechial

rash, epistaxis and herpes labialis. As the disease progresses, the liver and spleen frequently

become tender and palpable, and jaundice is common. There may be severe serosal and

intestinal haemorrhage, mental confusion and meningism. The fever ends in crisis between

the 4th and 10th days, often associated with profuse sweating, hypotension, and circulatory

and cardiac failure. There may be no further fever but, in a proportion of patients, after an

afebrile period of about 7 days, there are one or more relapses, which are usually milder and

less prolonged. In the absence of specific treatment, the mortality rate is up to 40%,

especially among the elderly and malnourished.

I

nvestigations and management

The organisms are demonstrated in the blood during fever either by dark ground microscopy

of a wet film or by staining thick and thin films.

The problems of treatment are to eradicate the organism, to minimise the severe Jarisch-

Herxheimer reaction which inevitably follows successful chemotherapy, and to prevent

relapses. The safest treatment is procaine penicillin 300 mg i.m., followed the next day by

0.5 g tetracycline. Tetracycline alone is effective and prevents relapse, but may give rise to a

worse reaction. Doxycycline 200 mg once by mouth in place of tetracycline has the

advantage of also being curative for typhus, which often accompanies epidemics of relapsing

fever.

Tick-borne relapsing fever

Soft ticks (Ornithodoros spp.) transmit B. duttoni (and several other borrelia species)

through saliva while feeding on their host. Those sleeping in mud houses are at risk, as the

tick hides in crevices during the day and feeds on humans during the night. Rodents are the

reservoir in all parts of the world except East Africa, where humans are the reservoir.

Clinical manifestations are similar to the louse-borne disease but spirochaetes are detected in

fewer patients on dark field microscopy. A 7-day course (due to a higher relapse rate than

louse-borne relapsing fever) of treatment with either tetracycline (500 mg 6-hourly) or

erythromycin (500 mg 6-hourly) is needed.

Leptospirosis

Microbiology and epidemiology

Leptospirosis is one of the most common zoonotic diseases, favoured by a tropical climate

5

and flooding during the monsoon but occurring world-wide.

Leptospirosis appears to be ubiquitous in wildlife and in many domestic animals. The

organisms persist indefinitely in the convoluted tubules of the kidney and are shed into the

urine in massive numbers, but infection is asymptomatic in the host.

Leptospires can enter their human hosts through intact skin or mucous membranes, but entry

is facilitated by cuts and abrasions. Prolonged immersion in contaminated water will also

favour invasion, as the spirochaete can survive in water for months. Leptospirosis is common

in the tropics and also in freshwater sports enthusiasts.

Clinical features

After a relatively brief bacteraemia, invading organisms are distributed throughout the body,

mainly in kidneys, liver, meninges and brain. The incubation period averages 1-2 weeks.

Four main clinical syndromes can be discerned.

1.

Bacteraemic leptospirosis

Bacteraemia with any serogroup can produce a non-specific illness with high fever,

weakness, muscle pain and tenderness (especially of the calf and back), intense headache and

photophobia, and sometimes

diarrhoea and vomiting. Conjunctival congestion is the only

notable physical sign. The illness comes to an end after about 1 week, or else merges into

one of the other forms of infection.

2.

Aseptic meningitis

this illness is very difficult to distinguish from viral meningitis. The conjunctivae may be

congested but there are no other differentiating signs. Laboratory clues include a neutrophil 5

leucocytosis, abnormal LFTs, and the occasional presence of albumin and casts in the urine.

3.

Icteric leptospirosis (Weil's disease)

Less than 10% of symptomatic infections result in severe icteric illness. Weil's disease is a

dramatic life-threatening event, 5characterized by fever, haemorrhages, jaundice and renal

impairment. Conjunctival hyperaemia is a frequent feature. The patient may have a transient

macular erythematous rash, but the characteristic skin changes are purpura and large areas of

bruising. In severe cases there may be epistaxis, haematemesis and melaena, or bleeding into

the pleural, pericardial or subarachnoid spaces. Thrombocytopenia, probably related to

activation of endothelial cells with platelet adhesion and aggregation, is present in 50% of

cases. Jaundice is deep and the liver is enlarged, but there is usually little evidence of hepatic

failure or encephalopathy. Renal failure, primarily caused by impaired renal perfusion and

acute tubular necrosis, manifests as oliguria or anuria, with the presence of albumin, blood

and casts in the urine.

Weil's disease may also be associated with myocarditis, encephalitis and aseptic meningitis.

Uveitis and iritis may appear months after apparent clinical recovery.

4.

Pulmonary syndrome

It is 5characterized by haemoptysis, patchy lung infiltrates on chest X-ray, and respiratory

failure. Total bilateral lung consolidation and ARDS with multi-organ dysfunction may

develop, with a high mortality (> 50%).

Diagnosis

:

A polymorphonuclear leucocytosis is accompanied in severe infection by thrombocytopenia

and elevated blood levels of creatine kinase. In jaundiced patients there is mild hepatitis and

the prothrombin time may be a little prolonged. The CSF in leptospiral meningitis shows a

6

variable cellular response, a moderately elevated protein level and normal glucose content.

In the tropics, dengue, malaria, typhoid fever, scrub typhus and hantavirus infection are

important differential diagnoses.

Definitive diagnosis of leptospirosis depends upon isolation of the organism, serological

tests or the detection of specific DNA.

Blood cultures are most likely to be positive if taken before the 10th day of illness.

Special media are required and cultures may have to be incubated for several weeks.

Leptospires appear in the urine during the 2nd week of illness, and in untreated

patients may be recovered on culture for several months.

Serological tests are diagnostic if seroconversion or a fourfold increase in titre is

demonstrated. The microscopic agglutination test (MAT) is the test of choice and can

become positive by the end of the first week. IgM ELISA and immunofluorescent

techniques are, however, easier to perform, while rapid immunochromatographic tests

are specific but of only moderate sensitivity in the 1st week of illness.

Detection of leptospiral DNA by PCR is possible in blood in early symptomatic

disease, and in urine from the 8th day of illness and for many months thereafter.

Management and prevention

The general care of the patient is critically important. Blood transfusion for haemorrhage and

careful attention to renal failure, the usual cause of death, are especially important. Renal

failure is potentially reversible with adequate support such as dialysis. The optimal

antimicrobial regimen has not been established. Most infections are self-limiting. Therapy

with either oral doxycycline (100 mg 12-hourly for 1 week) or intravenous penicillin (900

mg 6-hourly for 1 week) is effective but may not prevent the development of renal failure.

Parenteral ceftriaxone (1 g daily) is as effective as penicillin.