Dr. Ahmed Saleem

FICMS

TUCOM / 2015

GENERAL EXAMINATION

Setting:

The room should be private, warm and well lighted

The position of the examiner and the patient

Equipment

Wash/gel your hands

Handshake and introduction

Permission and sensitively, but adequately, expose the areas to be examined

General mental state and level of consciousness

Facial expression and hair

General demeanor

Normal, wasted, overweight, or have some skeletal or sexual characteristics that look

out of proportion.

IV access/Drains/Monitors

Complexion/Skin changes

Pallor

Cyanosis/Polycythemia

Jaundice

Hydration

Pigmentation/Tattoos

Excoriation/pruritus

Face, Eye, Mouth, LN

Hands and radial pulse (Nails, Temperature, Moisture, Color)

Operation Site/Dressing

Legs for edema/DVT

BP/RR/Temperature

Thank and cover the patient

* Baseline examination sequence

After introducing yourself and taking permission, stand on the right and start by inspection; then you

may say “The patient conscious, oriented and look well, no abnormal discoloration or pigmentation

+/- (IV access/Drains/Monitors) attached” then show the following while explaining to the examiner:

The eye for jaundice and pallor

The lips and mouth for cyanosis, pallor and hydration

Hands and radial pulse (Nails, Temperature, Moisture, Color)

Operation Site/Dressing

Legs for edema/DVT

BP/RR/Temperature

Thank and cover the patient

GENERAL EXAMINATION

Setting:

The room should be private, warm and well lighted

The position of the examiner and the patient

Equipment

Wash/gel your hands

Handshake and introduction

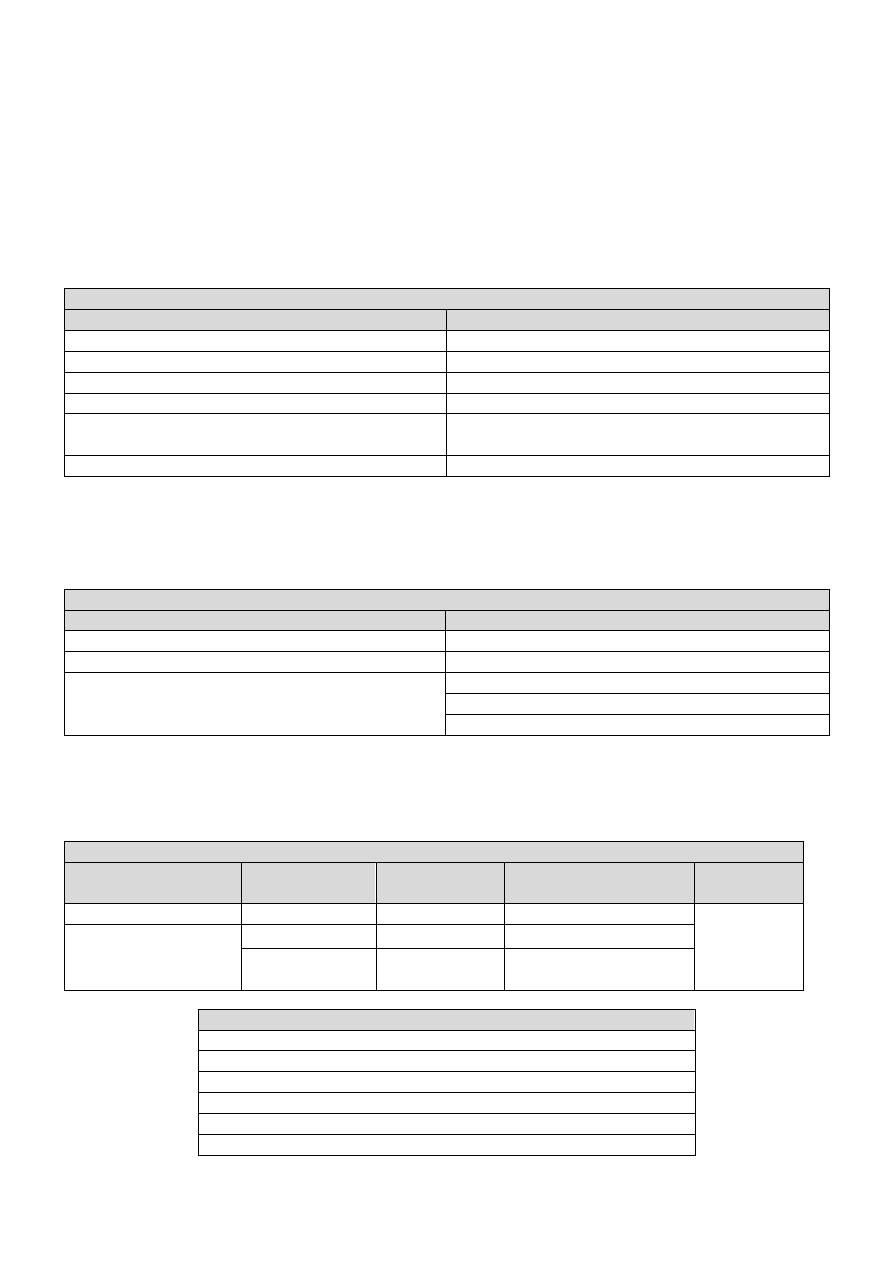

Information from a handshake

Features

Diagnosis

Cold, sweaty hands

Anxiety

Hot, sweaty hands

Hyperthyroidism

Cold, dry hands

Raynaud's phenomenon

Large, fleshy, sweaty hands

Acromegaly

Dry, coarse skin

Hypothyroidism

Manual occupation

Deformed hands/fingers

Dupuytren's contracture, Rheumatoid arthritis

Permission and sensitively, but adequately, expose the areas to be examined

General mental state and level of consciousness

Facial expression and hair

The common causes of hair loss

Local

General

Male balding

Hypothyroidism

Alopecia areata

Cytotoxic drugs

Skin infections

Hypopituitarism

Iron deficiency

Sever illness

General demeanor

Normal, wasted, overweight, or have some skeletal or sexual characteristics that look

out of proportion.

The common causes of wasting

In children

In young adults

In middle age

In old age

All age

groups

Severe gastroenteritis

Tuberculosis

Diabetes

Carcinoma

Starvation

Malabsorption

syndromes

Reticuloses

Thyrotoxicosis

Senility

Anorexia nervosa Carcinoma

Gross cardiorespiratory

disease

The common causes of an increase in weight

Obesity

Pregnancy

Interstitial fluid retention (renal, cardiac or hepatic failure)

Localized fluid retention (massive ovarian cysts, ascites)

Myxedema

Cushing’s syndrome

IV access/Drains/Monitors

Complexion/Skin and Discoloration

Pallor

Look at the color of the conjunctiva on the inner side of the lower eyelid, Look at

the color of the buccal mucous membrane, Stretch the skin of the palm and look at

the color of the palmar creases.

An important determinant of skin color is the relative amount of oxyhemoglobin and

deoxyhemoglobin. Oxyhemoglobin is a bright red pigment. An increase in its flow

beneath thinned facial skin causes the characteristic plethora of Cushing’s syndrome,

whereas a decrease in flow causes pallor.

Pallor can have many causes. It may be:

temporary, due to shock, hemorrhage or intense emotion

persistent, due to anemia or peripheral vasoconstriction.

Vasoconstriction is seen in patients with severe atopy – an inherited susceptibility to

asthma, eczema and hay fever. Pallor is a feature of anemia, but not all pale persons

are anemic; conjunctival and mucosal color is a better indication of anemia than skin

color. A pale skin resulting from diminished pigment occurs with hypopituitarism and

hypogonadism.

Cyanosis/Polycythemia

As blood passes through the capillary bed, oxygen is given up to metabolizing tissues to

produce deoxyhemoglobin. This has a darker, less red, more bluish pigment and its

presence in peripheral blood vessels in increased amounts causes the clinical sign of

cyanosis. There are two physiological types of cyanosis: peripheral and central.

Peripheral cyanosis is associated with increased extraction of oxygen from capillaries

when peripheral blood flow is slowed, often due to vasospasm caused by cold, heart

failure or anxiety. The cyanosed extremity is usually cold and the tongue is

unaffected. Any condition causing slowing of the peripheral circulation may lead to

peripheral cyanosis as there is more time for oxygen extraction. Central cyanosis is

caused by inadequate oxygenation of blood, in turn due to heart failure, serious

respiratory disease or mixing of venous and arterial blood across a right to left cardiac

shunt. In the latter situation, blood passes directly from the right to the left side of the

heart, without passing through the pulmonary circulation, thereby failing to become

oxygenated. Central cyanosis is generalized and the peripheries are often warm. At

least 5 g/dl of reduced hemoglobin is necessary to produce central cyanosis, and it is

therefore less marked in anemic patients. The cyanosis of heart failure is often due to

both peripheral and central causes. The presence of central cyanosis is best

appreciated at the lips, mucous membranes and conjunctivae, where the keratinized

skin is thinnest.

An excess of circulating red blood cells gives the patient a purple-red, florid

appearance. This may be mistaken for cyanosis. It differs from cyanosis in that it

heightens the color of all the skin, especially the cheeks, neck and backs of hands and

feet. The discoloration of cyanosis is usually limited to the tips of the hands, feet and

nose.

Jaundice

Hold the patient upper eyelid with one hand and ask the patient to follow your

finger of other hand downward to reveal the upper sclera, compare both sides.

Jaundice is a yellowish discoloration of the skin, sclerae and mucous membranes due to

hyperbilirubinemia. The yellow colour is first visible against the white background of

the sclera, but as the jaundice increases, the whole skin turns yellow. Bilirubin, a

breakdown product of the porphyrin ring of heme-containing proteins, is found in the

blood in two fractions—conjugated and unconjugated. The unconjugated fraction, also

termed the indirect fraction, is insoluble in water and is bound to albumin in the blood.

The conjugated (direct) bilirubin fraction is water soluble and can therefore be

excreted by the kidney. When measured by the original van den Bergh method, the

normal total serum bilirubin concentration is 17 μmol/L (1 mg/dL). Up to 30%, or 5.1

μmol/L (0.3 mg/dL), of the total is direct-reacting (or conjugated) bilirubin. Levels of

bilirubin >50 μmol/l are needed for clinical detection in good light. Unconjugated

bilirubin is insoluble and transported in plasma bound to albumin; it is therefore not

filtered by the renal glomeruli. In jaundice due to unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, the

urine is normal in color (acholuric jaundice. In the liver, bilirubin is conjugated to form

bilirubin diglucuronide and excreted, giving bile its characteristic green color. In

conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, the urine is dark brown in color due to the presence of

bilirubin diglucuronide. In the colon, conjugated bilirubin is metabolized by bacterial

flora to stercobilinogen and stercobilin which are excreted in the stool, contributing to

the brown color of stool. Stercobilinogen is absorbed from the bowel and excreted in

the urine as urobilinogen, a colorless, water-soluble compound.

Prehepatic jaundice In hemolytic disorders the accompanying anemic pallor combined

with jaundice may produce a pale lemon complexion. The stools and urine are normal

in color. Gilbert's syndrome is common and causes unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

Serum liver enzyme concentrations are normal and jaundice is mild (plasma bilirubin

<100 μmol/l) but increases during prolonged fasting or intercurrent febrile illness.

Hepatic jaundice Hepatocellular disease causes hyperbilirubinemia that is both

unconjugated and conjugated. Urine will be dark and stools normal in color.

Post-hepatic jaundice In biliary obstruction, conjugated bilirubin in the bile does not

reach the intestine, so the stools are pale. Conjugated bilirubin is soluble and filtered

by the kidney, so the urine is dark brown. Obstructive jaundice may be accompanied by

generalized itch (pruritus) due to skin deposition of bile salts. Obstructive jaundice with

abdominal pain is usually due to gallstones; if fever or rigors also occur (Charcot's

triad), ascending cholangitis is likely. Painless obstructive jaundice suggests malignant

biliary obstruction, e.g. cholangiocarcinoma or cancer of the head of the pancreas.

Obstructive jaundice can be hepatic as well as post-hepatic intrahepatic cholestasis,

e.g. primary biliary cirrhosis.

Hydration

Assess the state of hydration by looking for sunken orbits and dry mucous membranes.

If severe dehydration seems likely, test skin turgor. Gently pinch a fold of skin on the

neck or anterior chest wall, hold it for a few seconds and then release. Well-hydrated

skin springs back into position immediately, whereas dehydrated skin subsides

abnormally slowly.

Pigmentation/Tattoos

Excoriation/pruritus

Face, Eye, Mouth, LN

Hands and radial pulse (Nails, Temperature, Moisture, Color)

The majority of patients with finger clubbing have thoracic disease but it is also associated

with gastrointestinal disorders and can be familial. Rarely, clubbing develops relatively quickly

over several weeks, in empyema. Clubbing requires:

loss of the normal angle between the nail and nail bed

increased nail bed fluctuation

increased nail curvature in later stages

increased bulk of the soft tissues over the terminal phalanges.

Operation Site/Dressing

Legs for edema/DVT

Inspect the legs for obvious edema and examine for pitting edema. Press firmly but gently

for around 20 – 30 seconds behind the medial malleolus, over the dorsum of the foot and on

the shin. If edema is present, a depression/concavity will form.

The cardinal sign of subcutaneous edema is pitting of superficial tissues. Pitting on pressure

may not be demonstrable until body weight has increased by 10-15% and may be only

demonstrable on sacrum in bedridden patients. Day-to-day alterations in body weight are

usually the most reliable index of changes in body water. Hypothyroidism is characterized by

mucinous infiltration of tissues (myxedema). In contrast to edema, myxedema and chronic

lymphedema do not pit on pressure.

BP/RR/Temperature

Body temperature may be recorded in the mouth, axilla, ear or rectum. A ‘normal’ mouth

temperature is 35.8-37.2 °C. Those in the ear and rectum are 0.5°C higher and in the axilla

0.5°C lower. There is a diurnal variation in temperature; the lowest values are recorded in the

early morning with a maximum between 6 and 10 pm. In women, ovulation is associated with

a 0.5°C rise in temperature.

Thank and cover the patient

EXAMINATION OF THE ABDOMEN

Setting: …

Inspection:

General …

End of bed: Asymmetry/Distension

Umbilicus

Visible peristalsis

Lump: Physical signs

Patient reaction and lump changes with Respiration/Coughing

Striae, Scars, sinuses or fistulae, pigmentation

Dilated surface veins

Palpation:

Technique …

Ask about pain and its site

Light palpation for tenderness.

Deep palpation for tenderness.

Mild tenderness, Sever tenderness (Guarding), Rebound tenderness, Rigidity

If mass found; assess its physical characteristics

Palpation of the normal solid viscera

Liver

Gallbladder

Spleen

Right Kidney

Left Kidney

Urinary Bladder

Percussion:

General percussion

Defining the boundaries of abdominal organs and masses

Liver, spleen, urinary bladder, other masses

Detection of ascites

Auscultation:

Bowel sounds and vascular bruits

Never forget to examine:

Supraclavicular lymph glands

Hernia orifices and femoral pulses

Genitalia

Anal canal and rectum

Thank and cover the patient

EXAMINATION OF THE ABDOMEN

Setting: …

Stand on right side and the patient lie supine on a hard couch and head raised by 15–20° and

the arms by his side. The full extent of the abdomen must be visible and, ideally, patients

should be uncovered from nipples to knees. Many find this embarrassing and a compromise is

to cover the lower abdomen with a sheet or blanket while palpating the abdomen, but never

forget to examine the genitalia and the hernial orifices.

Inspection:

General …

End of bed: Asymmetry/Distension

Is the abdomen of normal contour and fullness, or distended? Is it scaphoid (sunken)?

Generalized fullness or distension may be due to fat, fluid, flatus, feces or fetus. Localized

distension may be symmetrical and centered around the umbilicus as in the case of small

bowel obstruction, or asymmetrical as in gross enlargement of the spleen, liver or ovary.

Make a mental note of the site of any such swelling or distension; think of the anatomical

structures in that region and note if there is any movement of the swelling, either with or

independent of respiration. Remember that chronic urinary retention may cause palpable

enlargement in the lower abdomen.

Umbilicus

Normally the umbilicus is slightly retracted and inverted. If it is everted, then an umbilical

hernia may be present and this can be confirmed by feeling an expansile impulse on

palpation of the swelling when the patient coughs. The hernial sac may contain omentum,

bowel or fluid. A common finding in the umbilicus of elderly obese people is a

concentration of inspissated desquamated epithelium and other debris (omphalolith).

Visible peristalsis

Seen in 3: Pyloric obstruction, Distal small bowel obstruction, Paralytic ileus.

Lump: Physical signs

Patient reaction and lump changes with Respiration/Coughing

Striae, Scars, sinuses or fistulae, pigmentation

In marked abdominal distension, the skin is smooth and shiny. Striae atrophica or

gravidarum are white or pink wrinkled linear marks on the abdominal skin. They are

produced by gross stretching of the skin with rupture of the elastic fibers and indicate a

recent change in size of the abdomen, such as is found in pregnancy, ascites, wasting

diseases and severe dieting. Wide purple striae are characteristic of Cushing’s syndrome

and excessive steroid treatment. Note any scars present, their site, whether they are old

(white) or recent (red or pink), linear or stretched (and therefore likely to be weak and

contain an incisional hernia). Pigmentation of the abdominal wall may be seen in the

midline below the umbilicus, where it forms the linea nigra and is a sign of pregnancy.

Erythema ab igne is a brown mottled pigmentation produced by constant application of

heat, usually a hot water bottle or heat pad, on the skin of the abdominal wall. It is a sign

that the patient is experiencing severe ongoing pain such as from chronic pancreatitis.

Dilated surface veins

Look for prominent superficial veins, which may be apparent in three situations: thin veins

over the costal margin, usually of no significance; occlusion of the inferior vena cava; and

venous anastomoses in portal hypertension. Inferior vena caval obstruction not only

causes edema of the limbs, buttocks and groins but, in time, distended veins on the

abdominal wall and chest wall appear. These represent dilated anastomotic channels

between the superficial epigastric and circumflex iliac veins below, and the lateral thoracic

veins above, conveying the diverted blood from the long saphenous vein to the axillary

vein; the direction of flow is therefore upwards. If the veins are prominent enough, try to

detect the direction in which the blood is flowing by occluding a vein, emptying it by

massage and then looking for the direction of refill. Distended veins around the umbilicus

(caput medusae) are uncommon but signify portal hypertension, other signs of which may

include splenomegaly and ascites. These distended veins represent the opening up of

anastomoses between portal and systemic veins and occur in other sites, such as

esophageal and rectal varices.

Palpation:

Technique

Palpation forms the most important part of the abdominal examination. Tell the patient to

relax as best he can and to breathe quietly, and assure him that you will be as gentle as

possible. Enquire about the site of any pain and come to this region last. These points,

together with unhurried palpation with a warm hand, will give the patient confidence and

allow the maximum amount of information to be obtained. When palpating, the wrist and

forearm should be in the same horizontal plane where possible, even if this means

bending down or kneeling by the patient’s side. The best palpation technique involves

moulding the relaxed right hand to the abdominal wall, not to hold it rigid. The best

movement is gentle but with firm pressure, with the fingers held almost straight but with

slight flexion at the metacarpophalangeal joints and certainly avoiding sudden poking with

the fingertips

Ask about pain and its site

Light palpation for tenderness.

Gently resting a hand on the abdomen and pressing lightly and systematically moved over

the whole of the abdomen, starting in left iliac fossa and move round in an anti-clockwise

direction to finish in the right iliac fossa.

Deep palpation for tenderness.

When no pain is elicited by systematic light palpation over the whole abdomen, repeat the

process, pressing more firmly and deeply to see if there is any deep tenderness.

Mild tenderness, Sever tenderness (Guarding), Rebound tenderness, Rigidity

If mass found; assess its physical characteristics

Palpation of the normal solid viscera

The liver

Start in the right iliac fossa. Place your hand flat on the abdomen with your fingers

pointing upwards and sensing fingers (index and middle) lateral to the rectus muscle,

so that your fingertips lie parallel to rectus sheath. Keep your hand stationary. Ask the

patient to breathe in deeply through the mouth. Feel for the liver edge as it descends

on inspiration. Move your hand progressively up the abdomen, 1 cm at a time,

between each breath the patient takes, until you reach the costal margin or detect the

liver edge. Another commonly employed though less accurate method of feeling for an

enlarged liver is to place the right hand below and parallel to the right subcostal

margin. The liver edge will then be felt against the radial border of the index finger. The

liver is often palpable in normal patients without being enlarged. The lower edge of the

liver can be clarified by percussion, as can the upper border in order to determine

overall size: a palpable liver edge can be due to enlargement or displacement

downwards by lung pathology. Hepatomegaly conventionally is measured in

centimeters palpable below the right costal margin, which should be determined with a

ruler if possible. Try to make out the character of its surface (i.e. whether it is soft,

smooth and tender as in heart failure, very firm and regular as in obstructive jaundice

and cirrhosis, or hard, irregular, painless and sometimes nodular as in advanced

secondary carcinoma). In tricuspid regurgitation, the liver may be felt to pulsate.

Occasionally a congenital variant of the right lobe projects down lateral to the

gallbladder as a tongue-shaped process, called Riedel’s lobe. Though uncommon, it is

important to be aware of this because it may be mistaken either for the gallbladder

itself or for the right kidney.

The upper and lower borders of the right lobe of the liver can be mapped out

accurately by percussion. Start anteriorly, at the fourth intercostal space, where the

note will be resonant over the lungs, and work vertically downwards. Over a normal

liver, percussion will detect the upper border, which is found at about the fifth

intercostal space (just below the right nipple in men). The dullness extends down to the

lower border at or just below the right subcostal margin, giving a normal liver vertical

height of 12-15 cm. The normal dullness over the upper part of the liver is reduced in

severe emphysema, in the presence of a large right pneumothorax and after

laparotomy or laparoscopy.

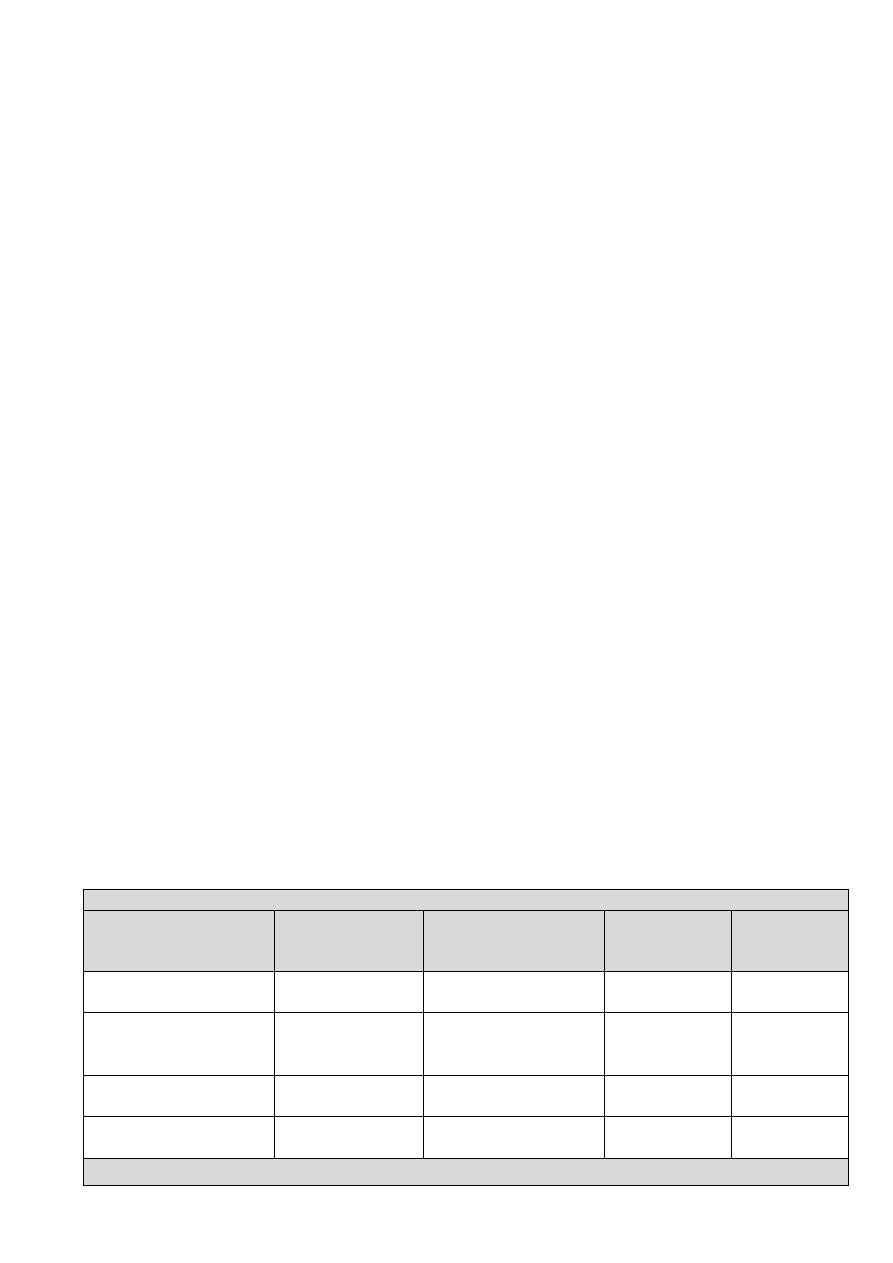

Causes of hepatomegaly

Chronic parenchymal

liver disease

Infectious

Malignancy

Haematological

disorders

Rarities

Alcoholic liver disease

Viral hepatitis

Primary hepatocellular

cancer

Lymphoma

Amyloidosis

Hepatic steatosis

Hydatid disease

Secondary metastatic

cancer

Leukaemia

Budd-Chiari

syndrome

Autoimmune hepatitis

Myelofibrosis

Sarcoidosis

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Polycythaemia

Right heart failure

Gallbladder

The gallbladder is palpated in the same way as the liver. The normal gallbladder cannot

be felt. When it is distended, however, it forms an important sign and may be palpated

as a firm, smooth, or globular swelling with distinct borders, just lateral to the edge of

the rectus abdominis near the tip of the ninth costal cartilage. It moves with

respiration. Its upper border merges with the lower border of the right lobe of the

liver, or disappears beneath the costal margin and therefore can never be felt. When

the liver is enlarged or the gallbladder grossly distended, the latter may be felt not in

the hypochondrium, but in the right lumbar or even as low down as the right iliac

region. The ease of definition of the rounded borders of the gallbladder, its

comparative mobility on respiration, the fact that it is not normally bimanually

palpable and that it seems to lie just beneath the abdominal wall helps to identify

such a swelling as gallbladder rather than a palpable right kidney. A painless

gallbladder can usually be palpated in the following clinical situations:

1-In a jaundiced patient with carcinoma of the head of the pancreas or other malignant

causes of obstruction of the common bile duct (below the entry of the cystic duct), the

ducts above the obstruction become dilated, as does the gallbladder (see Courvoisier’s

law, below).

2-In mucocele of the gallbladder, a gallstone becomes impacted in the neck of a

collapsed, empty, uninfected gallbladder and mucus continues to be secreted into its

lumen. Eventually, the uninfected gallbladder is so distended that it becomes palpable.

In this case, the bile ducts are normal and the patient is not jaundiced.

3-In carcinoma of the gallbladder, the gallbladder may be felt as a stony, hard, irregular

swelling, unlike the firm, regular swelling of the two above-mentioned conditions.

* Murphy’s sign

In acute inflammation of the gallbladder (acute cholecystitis), severe pain is present.

Often an exquisitely tender but indefinite mass can be palpated; this represents the

underlying acutely inflamed gallbladder walled off by greater omentum. Ask the

patient to breathe in deeply, and palpate for the gallbladder in the normal way; at the

height of inspiration, the breathing stops with a gasp as the mass is felt. This represents

Murphy’s sign. The sign is not found in chronic cholecystitis or uncomplicated cases of

gallstones.

* Courvoisier’s law

This states that in the presence of jaundice, a palpable gallbladder makes gallstone

obstruction of the common bile duct an unlikely cause (because it is likely that the

patient will have had gallbladder stones for some time and these will have rendered

the wall of the gallbladder relatively fibrotic and therefore non-distensible). However,

the converse is not true, because the gallbladder is not palpable in many patients who

do turn out to have malignant bile duct obstruction.

Spleen

An enlarged spleen appears below the tip of the tenth rib along a line heading

towards the umbilicus and, if really large, may extend into the right iliac fossa. A

normal spleen is not palpable.

To feel the spleen, place the fingertips of your right hand on the right iliac fossa just

below the umbilicus. Ask the patient to take a deep breath. If nothing abnormal is

felt, move your hand in stages towards the tip of the left tenth rib. When the costal

margin is reached, place your left hand around the lower left rib cage and lift the

lower ribs and the spleen forwards as the patient inspires. This manoeuvre

occasionally lifts a slightly enlarged spleen far enough forward to make it palpable.

Where considerable splenomegaly is present, its typical characteristics include a

firm swelling appearing beneath the left subcostal margin in the left upper

quadrant of the abdomen, which is dull to percussion, moves downwards on

inspiration, is not bimanually palpable, whose upper border cannot be felt (i.e. one

cannot ‘get above it’) and in which a notch can often, though not invariably, be

felt in the lower medial border. The last three features distinguish the enlarged

spleen from an enlarged kidney; in addition, there is usually a band of colonic

resonance anterior to an enlarged kidney.

Causes of splenomegaly

Infections

Rheumatological conditions

Hematological disorders

Rarities

Glandular fever

Rheumatoid arthritis (Felty's

syndrome)

Lymphoma and lymphatic

leukemias

Sarcoidosis

Malaria, kala azar

(leishmaniasis)

Systemic lupus erythematosus Myeloproliferative diseases,

polycythemia rubra vera and

myelofibrosis

Amyloidosis

Brucellosis, tuberculosis,

salmonellosis

Hemolytic anemia, congenital

spherocytosis

Glycogen storage

disorders

Bacterial endocarditis

Portal hypertension

Causes of hepatosplenomegaly

Lymphoma

Myeloproliferative diseases

Cirrhosis with portal hypertension

Amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, glycogen storage disease

Right Kidney

Place the right hand horizontally in the right lumbar region anteriorly with the left hand

placed posteriorly in the right loin. Push forwards with the left hand, press the right

hand inward and upward and ask the patient to take a deep breath in. The lower pole

of the right kidney, unlike the left, is commonly palpable in thin patients and is felt as a

smooth, rounded swelling which descends on inspiration and is bimanually palpable

and may be ‘ballotted’.

Left Kidney

The right hand is placed anteriorly in the left lumbar region while the left hand is

placed posteriorly in the left loin. Ask the patient to take a deep breath in, press the

left hand forward and the right hand backward, upward and inward. The left kidney is

not usually palpable unless either low in position or enlarged. Its lower pole, when

palpable, is felt as a rounded firm swelling between both right and left hands (i.e.

bimanually palpable) and it can be pushed from one hand to the other, in an action

which is called ‘ballotting’.

Urinary Bladder

Normally the urinary bladder is not palpable. When it is full and the patient cannot

empty it (retention of urine), a smooth firm regular oval-shaped swelling will be

palpated in the suprapubic region and its dome (upper border) may reach as far as the

umbilicus. The lateral and upper borders can be readily made out, but it is not possible

to feel its lower border (i.e. the swelling is ‘arising out of the pelvis’). The fact that this

swelling is symmetrically placed in the suprapubic region beneath the umbilicus, that

it is dull to percussion and that pressure on it gives the patient a desire to micturate,

together with the signs above, confirm such a swelling as the bladder. In women,

however, a mass that is thought to be a palpable bladder has to be differentiated from

a gravid uterus (firmer, mobile side to side and vaginal signs different), a fibroid uterus

(may be bosselated, firmer and vaginal signs different) and an ovarian cyst (usually

eccentrically placed to left or right side).

Percussion:

The technique of percussion was probably developed as a way of ascertaining how much

fluid remained in barrels of wine or other liquids. Effective percussion is a knack that

requires consistent practice; do so upon yourself or on willing colleagues, as percussion

can be uncomfortable for patients if performed repeatedly and inexpertly. The middle

finger of the left hand is placed on the part to be percussed and pressed firmly against it,

with slight hyperextension of the distal interphalangeal joint. The back of this joint is then

struck with the tip of the middle finger of the right hand (vice versa if you are left-handed).

The movement should be at the wrist rather than at the elbow. The percussing finger is

bent so that its terminal phalanx is at right angles and it strikes the other finger

perpendicularly. As soon as the blow has been given, the striking finger is raised: the action

is a tapping movement. The two most common mistakes made by the beginner are, first,

failing to ensure that the finger of the left hand is applied flatly and firmly and, second,

striking the percussion blow from the elbow rather than from the wrist.

General percussion over the abdomen: A dull area may draw your attention to a mass

that was missed on palpation and indicate a more detailed and careful palpation of the

area of dullness.

Defining the boundaries of abdominal organs and masses

Liver, spleen, urinary bladder, other masses

Detection of ascites: The use of ultrasound to detect ascites has shown that quite a lot

needs to be present to be detected clinically, probably more than 2 liters. It is unwise

and unreliable to diagnose ascites unless there is sufficient free fluid present to give

generalized enlargement of the abdomen.

The cardinal sign created by ascites is shifting dullness. A fluid thrill may also be present

but it would be unwise to diagnose ascites based on this sign without the presence of

shifting dullness.

Shifting dullness: With the patient supine, percuss from the midline out to the flanks.

Note any change from resonant to dull, along with the areas of dullness and resonance.

Keep your finger on the site of dullness in the flank and ask the patient to turn on to his

opposite side. Pause for at least 10 seconds to allow any ascites to gravitate, then

percuss again. If the area of dullness is now resonant, shifting dullness is present,

indicating ascites.

Fluid thrill: If the abdomen is tensely distended and you are not certain whether ascites

is present, look for the presence of a fluid thrill. Place the palm of your left hand flat

against the left side of the abdomen and flick a finger of your right hand against the

right side of the abdomen. If you feel a ripple against your left hand, ask an assistant to

place the edge of their hand on the midline of the abdomen. This prevents

transmission of the impulse via the skin rather than through the ascites. If you still feel

a ripple against your left hand, a fluid thrill is present (only detected in gross ascites).

Auscultation:

Bowel sounds and vascular bruits

With the patient lying on his back, place the stethoscope diaphragm to the right of the

umbilicus and do not move it. Bowel sounds are gurgling noises from the normal peristaltic

activity of the gut. They normally occur every 5-10 seconds, but the frequency varies.

Listen for up to 2 minutes before concluding that bowel sounds are absent. Absence of

bowel sounds implies paralytic ileus or peritonitis. In intestinal obstruction, bowel sounds

occur with increased frequency, volume and pitch, and have a high-pitched, tinkling

quality.

Listen above the umbilicus over the aorta for arterial bruits, which suggest an

atheromatous or aneurysmal aorta or superior mesenteric artery stenosis.

Now place the stethoscope 2-3 cm above and lateral to the umbilicus and listen for renal

artery bruits from renal artery stenosis.

Listen over the liver for bruits due to hepatoma or acute alcoholic hepatitis. A friction rub,

which sounds like rubbing your dry fingers together, may be heard over the liver

(perihepatitis) or spleen (perisplenitis).

A succussion splash sounds like a half-filled water bottle being shaken. Explain the

procedure to the patient then shake the abdomen by lifting him with both hands under the

pelvis. An audible splash more than 4 hours after the patient has eaten or drunk anything

indicates delayed gastric emptying, e.g. pyloric stenosis.

Never forget to examine:

Supraclavicular lymph glands

Hernia orifices and femoral pulses

Genitalia

Anal canal and rectum

Thank and cover the patient

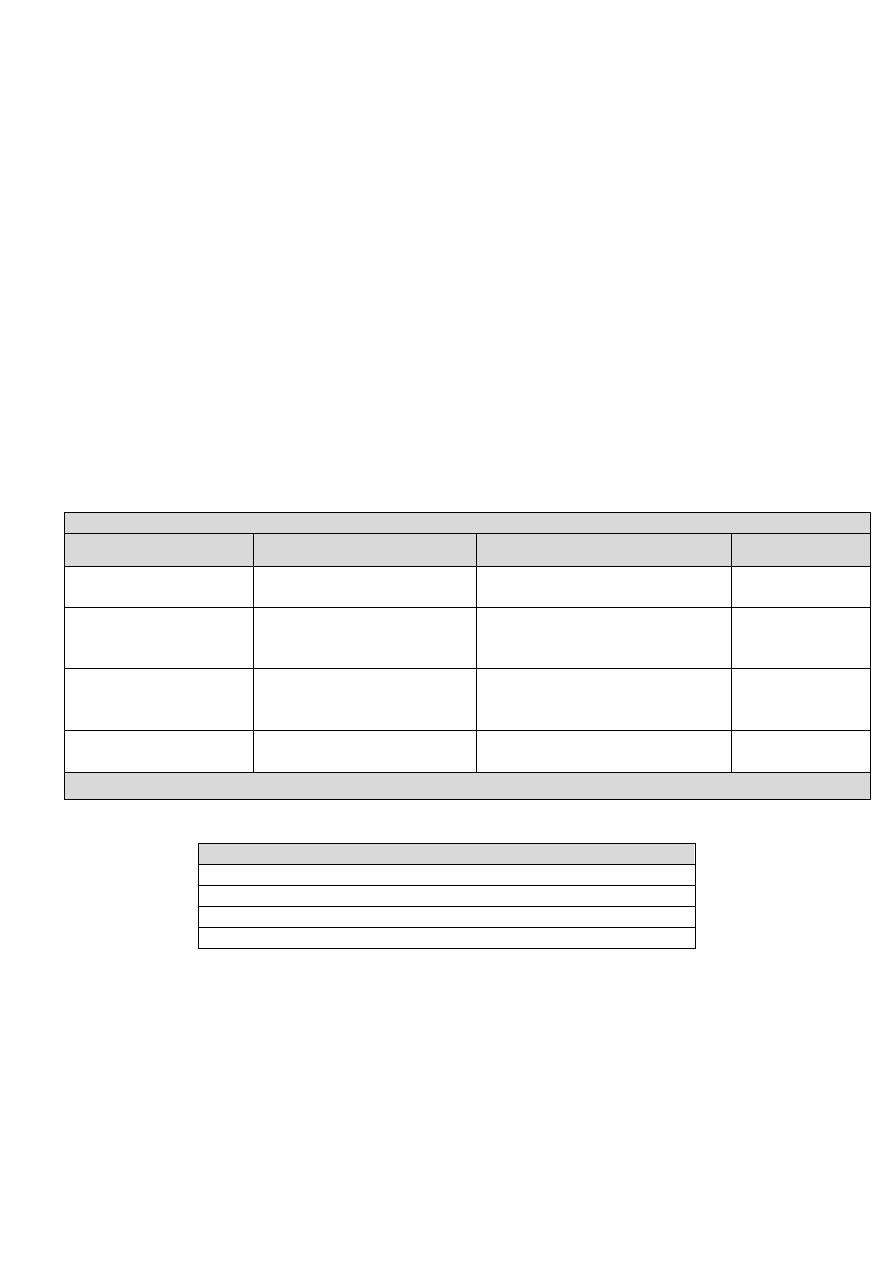

ANO-RECTAL EXAMINATION

Setting …

Uncover the patient

from the waist to the middle of the thighs.

The patient should lie in the left lateral position

with the neck and shoulders rounded so that the

chin rests on the chest, hips flexed to 90° or more,

but knees

flexed to slightly less than 90°. Ask the patient to move towards you so that his buttocks are up to the edge of

the bed. This makes inspection easier and tips the abdominal contents forwards, which helps the bimanual

examination.

Inspection:

Lift up the uppermost buttock with your left hand so that you can see the anus, peri-anal skin

and perineum clearly. Look for:

skin rashes and excoriation,

fecal soiling, blood or mucus,

scarring, or the opening of a fistula,

lumps and bumps (e.g. polyps, a peri-anal hematoma, prolapsed piles, or even a

carcinoma),

ulcers, especially fissures.

Palpation:

Before carrying out a digital examination, particularly if there is a history of pain on defecation,

place your fingers on either side of the anus and gently stretch the anal orifice. This is to see if

there is any spasm associated with a fissure, which may be visible. If there is spasm or a

fissure, in no circumstances carry out any instrumentation as this could cause severe pain.

Place the pulp of your gloved right index finger on the center of the anus, with the finger

parallel to the skin of the perineum and in the mid-line. Then press gently into the anal canal,

but at the same time press backwards against the skin of the posterior wall of the anal canal

and the underlying sling of the puborectalis muscle. This overcomes most of the tone in the

anal sphincter and allows the finger to straighten and slip into the rectum. Never thrust the tip

of your finger straight in.

The anal canal

As the finger goes through the anal canal, note:

The tone of the sphincter

Pain or tenderness

Thickening or masses.

The rectum

Feel all around the rectum as high as possible, and

Note the texture of the wall of the rectum and the presence of any masses or

ulcers. If you feel a mass, try to decide if it is within or outside the wall of the

rectum by testing the mobility of the mucosa over it. This is a most important

distinction.

Do not forget to feel the lower rectum, just above the anal canal. Posteriorly, the

rectum turns away at a right-angle, and it is easy to miss a small swelling in this

area.

Note the contents of the rectum. The rectum may be full of feces (hard or soft),

empty and collapsed, or empty but ‘ballooned out’. Feces may feel like a tumor but

are indentable, the only rectal mass that is.

If you can just detect a possible abnormality at your fingertip, ask the patient to

strain or push down. This will often move the mass down 1 or 2 cm or so and bring

it within your reach.

The recto-vesical/recto-uterine pouch

Turn your finger round so that the pulp feels forwards and can detect any masses

outside the rectum in the peritoneal pouch between the rectum and the bladder or

uterus. It takes practice to be able to tell the normal prostate and cervix from an

abnormal mass. Do not be downhearted if you get it wrong at first: experience and

confidence are needed.

Bimanual examination

The examination of the contents of the pelvis is helped if you place your left hand

on the abdomen and feel bimanually. This gives you a much better idea of the size,

shape and nature of any pelvic mass. You will find this method of examination

much more difficult in an obese patient.

The cervix and uterus

These structures are easy to feel per rectum and, with the help of bimanual

palpation; you should be able to define the shape and size of the uterus and any

adnexal masses. Do not call the hard mass that you can feel in the anterior rectal

wall a carcinoma until you are sure that it is neither the cervix nor a tampon.

The prostate and seminal vesicles

The normal prostate gland is firm, rubbery, bilobed and 2–3 cm across. Its surface

should be smooth, with a shallow central sulcus, and the rectal mucosa should

move freely over it. The seminal vesicles may occasionally be palpable just above

the upper lateral edges of the gland.

Benign hypertrophy of the prostate causes enlargement of the whole gland, which

bulges backwards into the rectum. However, the central sulcus is usually still there

unless the gland is very large. The gland may feel lobulated. The overlying rectal

mucosa remains uninvolved and mobile.

Carcinoma of the prostate may cause an irregular, hard enlargement which is often

unilateral. The edge of the enlarged area is indistinct. If the tumor has spread out

into the floor of the pelvis, you will feel thickening either side of the gland, which

can sometimes encircle the rectum. This lateral thickening is sometimes described

as ‘winging’ of the prostate. The central sulcus may be distorted or obliterated at

an early stage of the disease and the rectal mucosa fixed to the underlying gland.

Look at your finger, when you remove it from the rectum, to note the color of the feces

and the presence of blood or mucus.

Thank and cover the patient

EXAMINATION OF INGUINAL HERNIA

Setting …

*

Ask the patient to stand up

*

Always examine both inguinal regions.

Inspection:

Look at the lump from in front and assess:

the exact site and shape of the lump.

whether the lump extends down into the scrotum, if there are any other scrotal

swelling

any swelling on the ‘normal’ side.

Palpation:

Feel from the front

Examine the scrotum and its contents.

In men, first decide if the lump is a hernia or a true scrotal lump by examining its

upper edge.

Feel from the side

Having examined the scrotal contents and decided that you cannot get above the

lump, you can make a provisional diagnosis of inguinal hernia and proceed to

examine the lump itself. Stand at the side of the patient, on the same side as the

hernia. Place one hand in the small of the patient’s back to support him and your

examining hand on the lump with your fingers and arm roughly parallel to the

inguinal ligament and ascertain the physical characteristics of the lump.

Expansile cough impulse

Compress the lump firmly with your fingers, then ask the patient to turn his head

towards the opposite side, and then to cough. If the swelling becomes tense and

expands with coughing, it has a ‘cough impulse’. Movement of the swelling without

expansion or an increase in tension is not a cough impulse. The presence of an

expansile cough impulse is diagnostic of a hernia, but its absence does not exclude

the diagnosis.

Is the swelling reducible?

The main reason for standing at the side of the patient is to be able to place your

hand in exactly the same position as the patient places his own hand when he is

reducing or supporting the hernia. He puts his hand on the lump and lifts it

upwards and backwards. You must do the same. You can only do this if your arm

comes from a position above and behind the hernia. First, press firmly to reduce

the tension of the lump. Then gently compress the lower part of the swelling. As

the lump gets softer, lift it up towards the external ring. Once it has all passed in

through this point, slide your fingers upwards and laterally towards the internal

ring to see if the hernia can be controlled (kept inside) by pressure at this point. If

the lump reduces into or through the abdominal wall at a point above and medial

to the pubic tubercle, it is an inguinal hernia. If the point of reduction is below and

lateral to the pubic tubercle, it is a femoral hernia.

Note that this method of differentiation refers to the point where the lump

reduces, not the position of the unreduced hernia, because once a hernia reaches

the subcutaneous tissue it can expand and spread in any direction. If the hernia can

be held reduced only by pressure over the external inguinal ring, it is a direct

inguinal hernia. If it can be controlled by pressure over the internal ring, it is an

indirect inguinal hernia. If there is any difficulty in reducing the hernia, ask the

patient to lie down and try again. This will also allow you to examine the abdomen.

Remove your hand and watch the hernia reappear

The direction of movement of the swelling and the way in which it reappears will

help to confirm your deductions about its site of origin. A reappearing indirect

hernia will seem to slide obliquely downwards along the line of the canal,

whereas

a direct hernia will project directly forwards.

Percuss and auscultate the lump

Feel the other side

Examine the abdomen

Thank and cover the patient

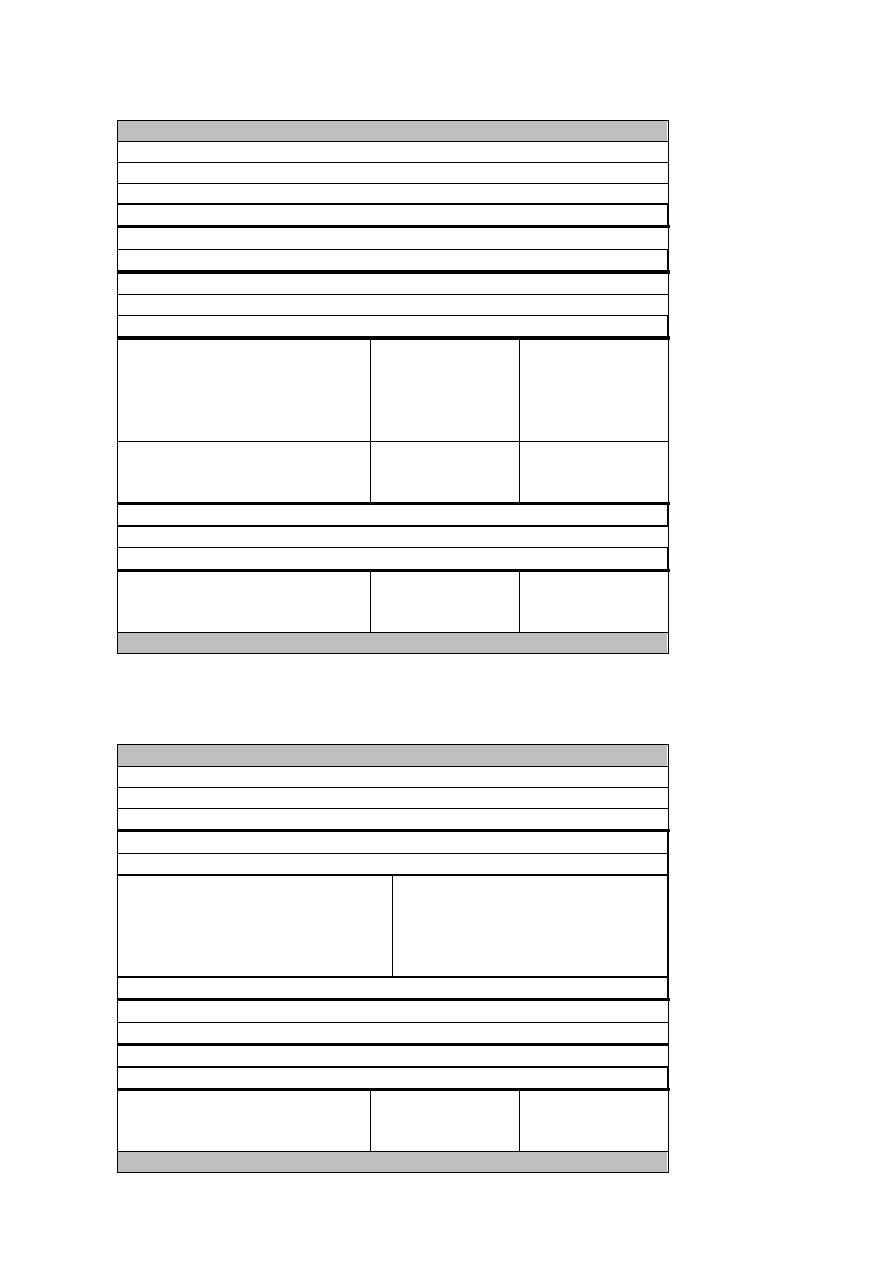

EXAMINATION OF A LUMP

Local examination

Site

Size

Shape

Surface

Depth

Color

Temperature

Tenderness

Edge

Composition:

consistence

fluctuation

fluid thrill

translucence

resonance

Solid, fluid or gas

pulsatility

compressibility

bruit

Vascular

Reducibility

Relations to surrounding structures - mobility/fixity

Regional lymph glands

State of local tissues:

arteries

nerves

bones and joints

General examination

EXAMINATION OF AN ULCER

Local examination

Site

Size

Shape

Base (Granulation tissue)

Depth

Edge

Sloping

Punched-out

Undermined

Rolled

Everted

Discharge

Temperature

Tenderness

Relations to surrounding structures - mobility/fixity

Regional lymph glands

State of local tissues:

arteries

nerves

bones and joints

General examination