Venous disorders:

Deep vein thrombosis:Etiology: exact cause is unknown but three factors contribute (Virchow's triad):

Changes in the vessel wall (endothelial damage)

Changes in the blood flow (stasis)

Changes in blood composition (hypercoagulation)

Clinical presentation:

AsymptomaticPain, redness, swelling with difficulty in walking

Features of pulmonary embolism may be the presenting feature in 30% of the patients

On examination:

Pitting oedema of the ankle,Dilated surface veins,

A stiff calf

Tenderness.

Homans’ sign – resistance (not pain) of the calf muscles to forcible dorsiflexion – is not absolute and should be abandoned.

A low-grade pyrexia may be present

Signs of pulmonary embolism or pulmonary hypertension

Investigations:

D-dimer measurement: if levels are normal, there is no indication for further investigations as the possibility of DVT is very remote.

Duplex ultrasound: loss of normal vein compressibility with filling defects in the flow

Ascending and descending venography; only indicated when surgical intervention is needed.

Prophylaxis:

Patients who are being admitted for surgery can be graded as low, moderate or high risk.Low-risk patients are young, with minor illnesses, who are to undergo operations lasting 30 min or less.

Moderate-risk patients are those over the age of 40 or those with a debilitating illness or who are to undergo major surgery.

High-risk patients are those over the age of 40 who have serious accompanying medical conditions, such as stroke or myocardial infarction, or who are undergoing major surgery with an additional risk factor such as a past history of venous thromboembolism or known malignant disease.

Mechanical prophylaxis include:

graduated elastic compression stockings

external pneumatic compression

passive foot movement (foot paddling machine)

simple limb elevation

Pharmaceutical prophylaxis:

low molecular weight heparin

unfractionated heparin

warfarin

Patients with low risk need no prophylaxis other than early postoperative mobilization. Those with moderate risk need either pharmaceutical or mechanical prophylaxis while those with high risk need both mechanical and pharmaceutical prophylaxis.

Medical treatment:

admission to hospital and bed rest

anticoagulant therapy (heparin and warfarin)

leg elevation

elastic compressive bandage from the toes to the upper thigh

patients with phlegmasia cerulea dolens need thrombolytic therapy

Surgical Treatment:

Venous thrombectomy: only indicated in patients with phlegmasia cerulea dolens with contraindication to thrombolytic therapyInferior vena cava filter: indicated in patients with:

Recurrent thromboembolism despite adequate anticoagulation

Progressing thromboembolism despite adequate anticoagulation

Complication of anticoagulants

Contraindication to anticoagulants

Pulmonary embolism:

Pulmonary thromboembolism is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. After an acute, major thromboembolic episode, approximately 15–20% of patients die within 48 hours. So invasive therapy for acute pulmonary embolism should be considered in those 15-20% of patients with fatal outcomes.Pathophysiology of pulmonary embolism

The hemodynamic response to a large, sudden pulmonary embolus relates to a variety of factors,the size of the embolus,

the degree of obstruction that it produced in the pulmonary vascular bed,

the underlying function of the lung that remains perfused.

In addition to the mechanical factor of pulmonary artery obstruction, there are hormonal factors that can increase pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) at the time of acute pulmonary embolism due to products released from the platelets within the embolus, the neutrophils and the blood vessel endothelial cells. Thus some patients with a relatively small embolus may have an exaggerated response to the degree of pulmonary vascular obstruction.

In patients without preexisting cardiac or pulmonary disease, only when the acute pulmonary obstruction exceeds 50–60% of the pulmonary vascular bed that cardiac and pulmonary compensatory mechanisms are overcome and cardiac output begins to fall.

With the sudden pulmonary artery obstruction, right ventricular failure occurs, which is accompanied by systemic hypotension as the amount of blood reaching the left ventricle decreases.

Clinical presentation:

Acute pulmonary embolism usually presents suddenly. Symptoms and signs vary with the extent of blockage, the magnitude of humoral response, and the pre-embolus reserve of the cardiac and pulmonary systems of the patient. The acute disease is conveniently stratified into minor, major (submassive), or massive embolism.

For patients with minor pulmonary embolism, physical examination may reveal tachycardia, rales, low-grade fever, and sometimes a pleural rub. Heart sounds and systemic blood pressure are often normal. Arterial blood gases are normal. Pulmonary angiograms typically show less than 30% occlusion of the pulmonary arterial vasculature.

Major pulmonary embolism is associated with dyspnea, tachypnea, dull chest pain, syncope and some degree of cardiovascular changes manifested by tachycardia, mild to moderate hypotension, and elevation of central venous pressure. In contrast to massive pulmonary embolism, patients with major embolism are hemodynamically stable and have adequate cardiac output. Blood gases reveal moderate hypoxia, and mild hypocarbia. Echocardiograms may show right ventricular dilatation. Pulmonary angiograms indicate that 30–50% of the pulmonary vasculature is blocked.

Massive pulmonary embolism is truly life-threatening and is defined as a pulmonary embolism that causes hemodynamic instability. It is usually associated with occlusion of more than 50% of the pulmonary vasculature, but may occur with much smaller occlusions, particularly in patients with preexisting cardiac or pulmonary disease. Patients develop acute dyspnea, tachypnea, tachycardia, and sweating and may lose consciousness. Both hypotension and low cardiac output are present. Cardiac arrest may occur. Neck veins are distended, and central venous pressure is elevated. Blood gases show severe hypoxia, hypocarbia, and acidosis. Urine output falls, and peripheral pulses and perfusion are poor.

Investigations:

ECG: tachycardia and nonspecific changes. The major value of the electrocardiogram is excluding a myocardial infarction.X-ray may show oligemia or linear atelectasis, both of which are nonspecific findings.

Ventilation–perfusion (V/Q) scans may provide confirmatory evidence, but these studies may be unreliable because pneumonia, atelectasis, previous pulmonary emboli, and other conditions may cause a false positive result. But a negative V/Q scan exclude the diagnosis of clinically significant pulmonary embolism.

Pulmonary angiograms (conventional angiography or CT angiography) provide the most definitive diagnosis for acute pulmonary embolism as it appears as filling defects or obstruction of pulmonary arterial branches.

Echocardiography both transthoracic or transesophageal may show an embolus obstructing the main pulmonary artery but will not visualize the lobar pulmonary arteries

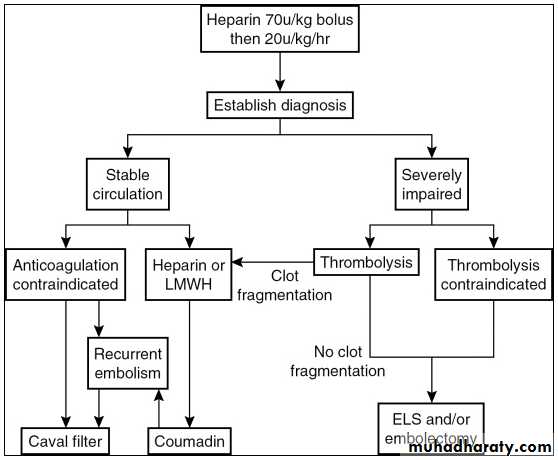

Treatment of pulmonary embolism:

The majority of patients who die of pulmonary embolism do so within 2 hours of the initial acute event, before the diagnosis can be firmly established, and before effective therapy can be instituted.

Conservative medical treatment:

Supplementary O2 (usually such patients are already in an ICU, if not need to immediately do so)Patients in respiratory distress will need mechanical ventilation

Invasive cardiac monitoring through both arterial line and central venous line for estimation of cardiac output and serial arterial blood gas measurement.

Pharmaceutical myocardial support (positive inotropic agents) and sometimes even mechanical myocardial support (like intra-aortic balloon pump).

Immediate anticoagulation with i.v. heparin preferably by infusion technique.

Consider thrombolysis in patients with major-to-massive pulmonary embolism. Still, thrombolytic therapy is contraindicated in patients with fresh surgical wounds, anemia, recent stroke, peptic ulcer, or bleeding dyscrasias.

Surgical treatment:

Emergency pulmonary embolectomy is indicated for suitable patients with life-threatening circulatory insufficiency, where the diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism has been established.

Indications for acute surgical intervention include the following:

Critical hemodynamic instability or severe pulmonary compromise

Patients in whom thrombolytic or anticoagulation therapy is absolutely contraindicated,

The presence of a large clot trapped within the right atrium or ventricle

Pulmonary embolectomy is done through a median sternotomy with total anticoagulation, a cardiopulmonary bypass machine, and mild to moderate hypothermia. The main pulmonary artery is opened and the embolus with its propagating thrombus removed by forceps, suction, and embolectomy catheter. After which the patient is weaned off the cardiopulmonary machine and the chest is closed. Dramatic improvement in his hemodynamics is noted immediately.