Fifth stage

PsychiatryLec-4

د. الهام

30/10/2016

Panic disorderPanic attack

Essence

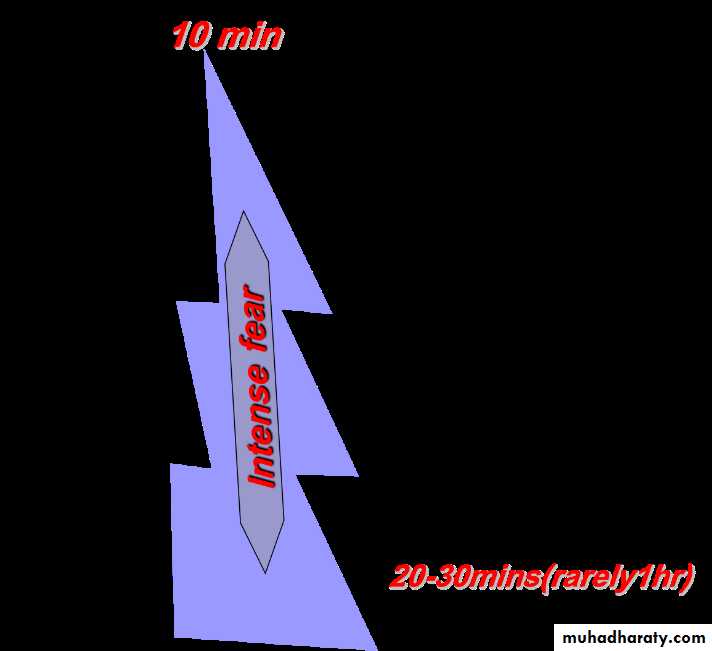

Panic attack A period of intense fear characterised by a constellation of symptoms that develop rapidly, reach a peak of intensity in about 10 mins, and generally do not last longer than 20-30 mins (rarely over 1 hr).

Attacks may be either

spontaneous (out of the blue) or

situational (usually where attacks have occurred previously).

Sometimes attacks may occur during sleep (nocturnal panic attacks), and

rarely, physiological symptoms of anxiety may occur without the psychological component (non-fearful panic attacks).

Panic disorder

Recurrent panic attackswhich are not secondary to

substance misuse,

medical conditions, or

another psychiatric disorder.

Frequency of occurrence may vary from

many attacks a day, to

only a few attacks a year.

There is usually the persistent worry about having another attack or the consequences of the attack (which may lead to phobic avoidance of places or situations), and significant behavioural changes related to the attack.

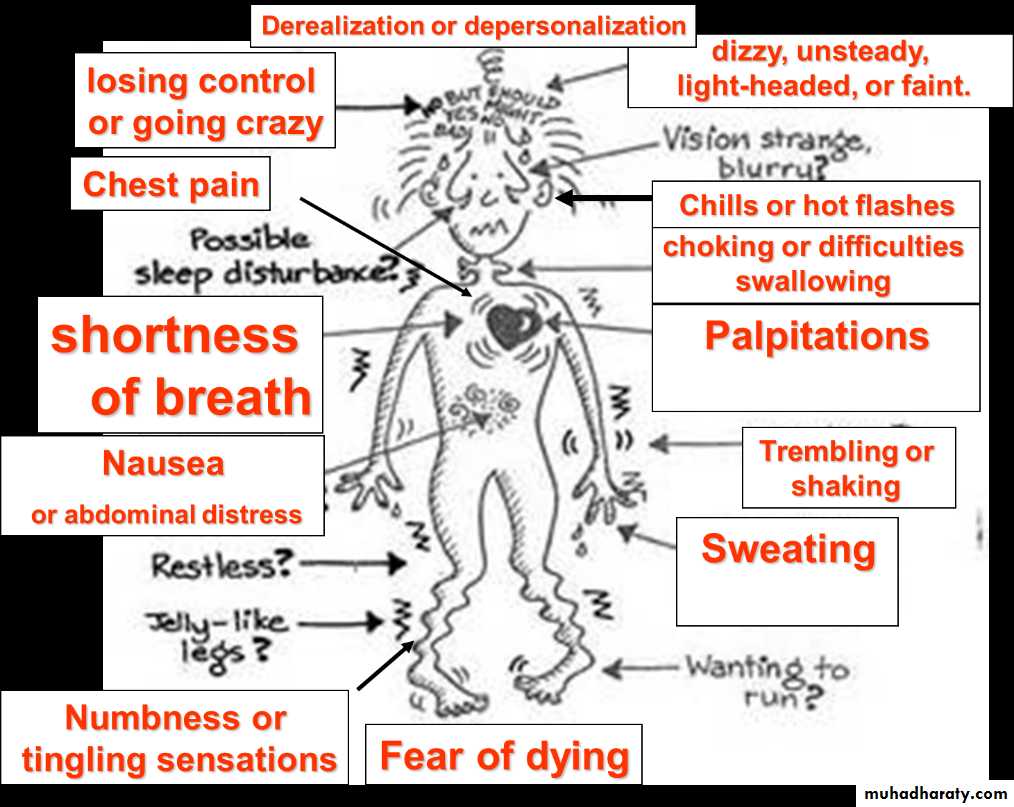

Symptoms/signs of panic attack

Symptoms associated with panic attacks (in order of frequency of occurrence)Palpitations, pounding heart, or accelerated heart rate.

Sweating.

Trembling or shaking.

Sense of shortness of breath or smothering.

Feeling of choking or difficulties swallowing (globus hystericus).

Chest pain or discomfort.

Nausea or abdominal distress.

Feeling dizzy, unsteady, light-headed, or faint.

Derealization or depersonalization (feeling detached from oneself or one's surroundings).

Fear of losing control or going crazy.

Fear of dying (angor animus).

Numbness or tingling sensations (paraesthesia).

Chills or hot flashes.

Symptoms/signs of panic attack

Physical symptoms/signs are related to autonomic arousal (e.g. tremor, tachycardia, tachypnoea, hypertension, sweating, GI upset) which are often compounded by HVS (in 50-60% of cases).Concerns of death from cardiac or respiratory problems may be a major focus, leading to patients presenting (often repeatedly) to emergency medical services.

Panic disorder may be undiagnosed in patients with unexplained medical symptoms (chest pain, back pain, GI symptoms including IBS, fatigue, headache, dizziness, or multiple symptoms).

Thoughts of suicide (or homicide) should be elicited as acute anxiety (particularly when recurrent) can lead to impulsive acts (usually directed towards self). Risk of attempted suicide is substantially raised where there is comorbid depression, alcohol misuse, or substance misuse.

Epidemiology

Lifetime prevalence:4.2% for panic disorder,

8% for panic attacks

Women are 2-3 times more likely to be affected than men.

Age of onset has a bimodal distribution with highest peak incidence at 15-24 yrs and a second peak at 45-54 yrs. Rare after age 65.

Differential diagnosis

Other anxiety or related disorder (panic attacks may be part of the disorder),substance or alcohol misuse/withdrawal (e.g. amphetamines, caffeine, cocaine, theophylline, sedative-hypnotics, steroid),

mood disorders,

psychiatric disorders secondary to medical conditions,

medical conditions presenting with similar symptoms (e.g. endocrine: carcinoid syndrome, Cushing's disease/syndrome, hyperthyroidism, hypoglycemia, hypoparathyroidism, phaeochromocytoma; haematological: anaemia, cardiac: arrhythmias, mitral valve prolapse, MI; respiratory: COPD/asthma, HVS; neurological: epilepsy(esp. TLE, vestibular dysfunction).

Investigations

There are no specific tests for panic disorder, however basic investigations should be performed to exclude physical causes (e.g. FBC, U&Es, glucose, TFTs, ECG, and if supported by history/physical examination: toxicology, Ca2+, urinary VMA/pHVA, ECHO, and EEG).

Aetiological models

The serotonergic model

Exaggerated post-synaptic receptor response to synaptic serotonin, possibly secondary to subsensitivity of 5HT1A receptors.

The noradrenergic model

Increased adrenergic activity, with hypersensitivity of presynaptic alpha2 receptors. (Locus coeruleus activity affects the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the firing rate is increased in panic.)

The GABA model

Decreased inhibitory receptor sensitivity, with resultant excitatory effect.

Cholecystokinin-pentagastrin model

Pentagastrin induces panic in a dose-dependent fashion in patients with panic disorder.

The lactate model

Postulated aberrant metabolic activity induced by lactate, from studies involving exercise-induced panic attacks (replicated by IV lactate infusion).

The false suffocation carbon dioxide hypothesis

Explains panic phenomena by hypersensitive brainstem receptors.

The neuroanatomical model

Suggests that panic attacks are mediated by a ˜fear network in the brain that involves the amygdala, the hypothalamus, and the brainstem centres.

The genetic hypothesis

Panic disorder has moderate heritability of around 30-40% (from family and twin studies).

Most studies to date suggest that vulnerability is genetically determined, but critical stressors are required to develop clinical symptoms.

The recently discovered genomic duplication (DUP25) on chromosome 15 (found in 7% of the population, but -95% of patients with panic disorder) is perhaps the best evidence yet for genetic susceptibility.

Management guidelines

Combination of pharmacological and psychological treatments may be superior to single approach.

Pharmacological

SSRIs (e.g. paroxetine [at least 40 mg], fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram, sertraline) are recommended as the drug of choice (unless contraindicated).

In view of the possibility of initially increasing panic symptoms, start with low dose and gradually increase.

Beneficial effect may take 3-8 weeks.

Alternative antidepressant TCAs (e.g. imipramine or clomipramine) although not specifically licensed in the UK have been shown to be 70-80% effective (possible alternatives include: desipramine, doxepin, nortryptiline, or amitriptyline.)

MAOIs (e.g. phenelzine) again not licensed, but may be superior to TCAs (for severe, chronic symptoms).

There is also some favourable evidence for RIMAs (e.g. moclobemide).

BDZs (e.g. alprazolam or clonazepam) should be used with caution (due to potential for abuse/dependence/cognitive impairment) but may be effective for severe, frequent, incapacitating symptoms.

Use for 1-2 weeks in combination with an antidepressant may cover symptomatic relief until the antidepressant becomes effective.

N.B. Anti-panic effects do not show tolerance, although sedative effects do.

If initial management is ineffective

Consider change to a different class agent (i.e. TCA, SSRI, MAOI) or

combination (e.g. TCA+Lithium, SSRI+TCA).

If treatment-resistant consider alternative agent (e.g. carbamazepine, valproate, gabapentin, low-potency BDZ [diazepam may need high dose], venlafaxine, inositol, verapamil).

If successful

Continue treatment for -1yr before trial discontinuation (gradual tapering of dose).

Do not confuse withdrawal effects (10-20% of patients) with re-emergence of symptoms (50-70% of patients).

If symptoms recur, continue for -1yr before considering second trial discontinuation.

(N.B. Patient may wish to continue treatment, rather than risk return of symptoms).

Psychological

- Behavioural methods:

to treat phobic avoidance by exposure, use of relaxation, and control of hyperventilation (have been shown to be 58-83% effective).

- Cognitive methods:

teaching about bodily responses associated with anxiety,

education about panic attacks,

modification of thinking errors.

- Psychodynamic methods:

there is some evidence for brief dynamic psychotherapy, particularly emotion-focused treatment (e.g. panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy), where typical fears of being abandoned or trapped are explored.

Issues of comorbidity

In view of high levels of comorbidity, treatment of these conditions should not be neglected.

For the other anxiety disorders and depression, this issue is somewhat simplified by the fact that SSRIs and other antidepressants have been shown to be effective for these conditions too. However, behavioural interventions (e.g. for OCD, social phobia) should also be considered.

Alcohol/substance abuse may need to be addressed first, but specific treatment for persistent symptoms of panic ought not to be overlooked.

Emergency treatment of an acute panic attack

Maintain a reassuring and calm attitude (most panic attacks spontaneously resolve within 30 mins).

If symptoms are severe and distressing consider prompt use of BDZs

immediate relief of anxiety may help reassure the patient,

provide confidence that treatment is possible, and

reduce subsequent emergency presentations.

If first presentation, exclude medical causes (may require admission to hospital for specific tests).

If panic attacks are recurrent, consider differential diagnosis for panic disorder and address underlying disorder (may require psychiatric referral).