1

NUTRITIONAL SUPPORT OF THE SURGICAL PATIENT

DR. N P LATCHMANAN

COMMENTATORS : DR V. PADAYACHY, P REDDY

MODERATOR : PROF. AA HAFFEJEE

INTRODUCTION

While most patients undergoing elective operations easily tolerate a brief period of

perioperative starvation, as many as 50 per cent of hospital patients may be nutritionally

compromised, depending on the definition. Nutritional status directly impacts on patient

care and adequate attention to nutritional issues can help to minimize morbidity and

complications

Steps to Optimal Nutrition Support

The five steps to optimal nutrition support are:

1) Begin when the benefits are likely to exceed the risk,

2) Set protein and calorie goals,

3) Choose and establish a method for administering the nutrients, enteral (site and

route) or parenteral (peripheral or central),

4) Choose or design a formula suitable for the particular patient, and

5) Monitor the patient for adequacy of nutrient intake and to avoid or minimize

complications.

NUTRITIONAL REQUIREMENTS

Protein

Protein is perhaps the most important nutrient. Although protein can be degraded and

used for gluconeogenesis, this yields only one-fourth of the energy required for protein

synthesis and is thus a wasteful process. A primary goal in nutritional support is to

provide adequate non-protein sources of fuel so that protein catabolism is minimized.

2

Protein requirements

The average normal protein requirement of 'high biologic value protein' is 0.8 g/kg or 56

to 60 g/day. And may increase to 1-2g/kg/day in stressed patients.

Assuming an adequate non-protein energy supply, most amino acids can be recycled. In

this fashion, only small amounts of essential amino acids are needed in order to maintain

nitrogen equilibrium. In adults, 19 to 20 per cent of protein intake should be essential

amino acids. This percentage should increase with depletion or injury.

Amino Acids

Humans cannot synthesize the essential amino acids. Thus, they must be obtained from

the diet. In addition, several other amino acids are conditionally indispensable, as their

low synthetic rates may be exceeded by increased requirements, especially in infants..

The semi-essential amino acid glutamine has recently received a great deal of attention.

Glutamine is abundant in the circulation and serves as a precursor for other amino acids

and proteins. Glutamine also serves as the major energy substrate for the intestinal

mucosa, as a nitrogen transporter between organs, and as an important route of ammonia

detoxification during acidemia. Enteral glutamine supplementation may promote small

bowel adaptation and lead to increased intestinal mucosa villous height and enterocyte

protein content, but this effect is not universally seen with parenteral glutamine

Nitrogen losses and balance

One gram of nitrogen equals 6.25 g of protein.

Obligate nitrogen losses are 56 to 57 mg/kg per day.

N

loss

= 24 h urinary urea nitrogen + 4 g/day (fecal and non-urinaryloss)

Calories

There are three major sources of energy: protein, fat, and carbohydrates. Of normal daily

energy expenditure, 85 per cent is from fat and carbohydrates, and 15 per cent from

protein.

Protein as an energy source

Of the 15 per cent of normal daily energy expenditure supplied by protein, approximately

50 per cent of this is through direct oxidation of branched chain amino acids to high-

energy phosphate. The remainder is via gluconeogenesis. Protein breakdown yields

4 kcal/g

3

Carbohydrates as an energy source

Glucose yields about 4 kcal/g through glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Glycogen breakdown yields only 1 to 2 kcal/g. Most carbohydrates in parenteral nutrition

are supplied in the form of dextrose, which provides 3.4 kcal/g.

Glycogen stores, however, are exhausted within 24 h of initiation of a fast, and the body

then becomes dependent on gluconeogenesis as a source of glucose.

At least 400 cal/day in the form of exogenously administered glucose are required to

minimize proteolysis.

Fat as an energy source

Fat about 9 kcal/g. After lipolysis, free fatty acids are released into the circulation. Free

fatty acids actually circulate bound non-covalently to albumin. Nearly all tissues, with the

notable exception of the brain, can utilize fatty acids as an energy source

Determination of caloric needs

Caloric needs are related to the metabolic rate, which in turn is demonstrated by the

formula:

metabolic rate = 4.83 × Vo

2

where Vo

2

is oxygen consumption in liters per unit of time. Furthermore, the respiratory

quotient (RQ), a ratio of carbon dioxide produced to oxygen consumed, can be used to

estimate utilization of the various caloric sources by the following formula:

RQ = Vco

2

/ Vo

2

An RQ of 1 is consistent with pure carbohydrate utilization.

An RQ of 0.7 is consistent with utilization of fat.

An RQ of less than 0.7 indicates ketogenesis.

In clinical practice, and RQ of greater than 1 is uncommon, but this may indicate

overfeeding.

An RQ of between 0.8 and 1, indicating mixed substrate utilization, is desirable.

The basal energy expenditure (BEE) can be estimated from the

4

Harris–Benedict equation:

BEE (men) = 66.47 + [13.75 × W] + [5 × H] – [6.76 × A]

BEE (women) = 655.1 + [9.56 × W] + [1.85 × H] – [4.68 × A]

where W is weight in kilograms, H is height in centimetres, and A is age in years.

The additional caloric needs due to illness or other metabolic stress can then be calculated

by multiplying the BEE by an injury factor:

minor operation = 1.2 (20 per cent increase)

skeletal trauma = 1.35 (35 per cent increase)

major sepsis = 1.6 (60 per cent increase)

severe thermal injury = 2.10 (110 per cent increase)

This estimate can be further refined to account for activity by multiplication by 1.2 if the

patient is confined to bed and 1.3 if the patient is not confined to bed. Therefore, caloric

needs equal:

BEE × injury factor × activity factor

Calorie to nitrogen ratio

Non protein energy is usually required at 30-35 kcal/kg/day

A non pretein energy : Nitrogen ratio of 100 – 200 is required to prevent protein

breakdown for energy

5

NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT

PARAMETERS

1. Clinical:

General appearance (oedema, ascites, cahexia, obesity, skin changes)

2. Anthropometry

• Midarm muscle circumference: < 23cm (male) & < 22cm (female) indicates

malnutrition.

• Triceps skinfold thickness: < 10mm (male) & < 13mm (female) indicates

malnutrition.

• Handgrip dynometry .

Body Mass Index (kg/m

2

)

=

18.5-25

=

normal

=

< 15

=

significant increase in morbidity

= <

18.5

=

associated

with longer hospital stay

=

> 30

=

obesity, increased incidence of heart disease,

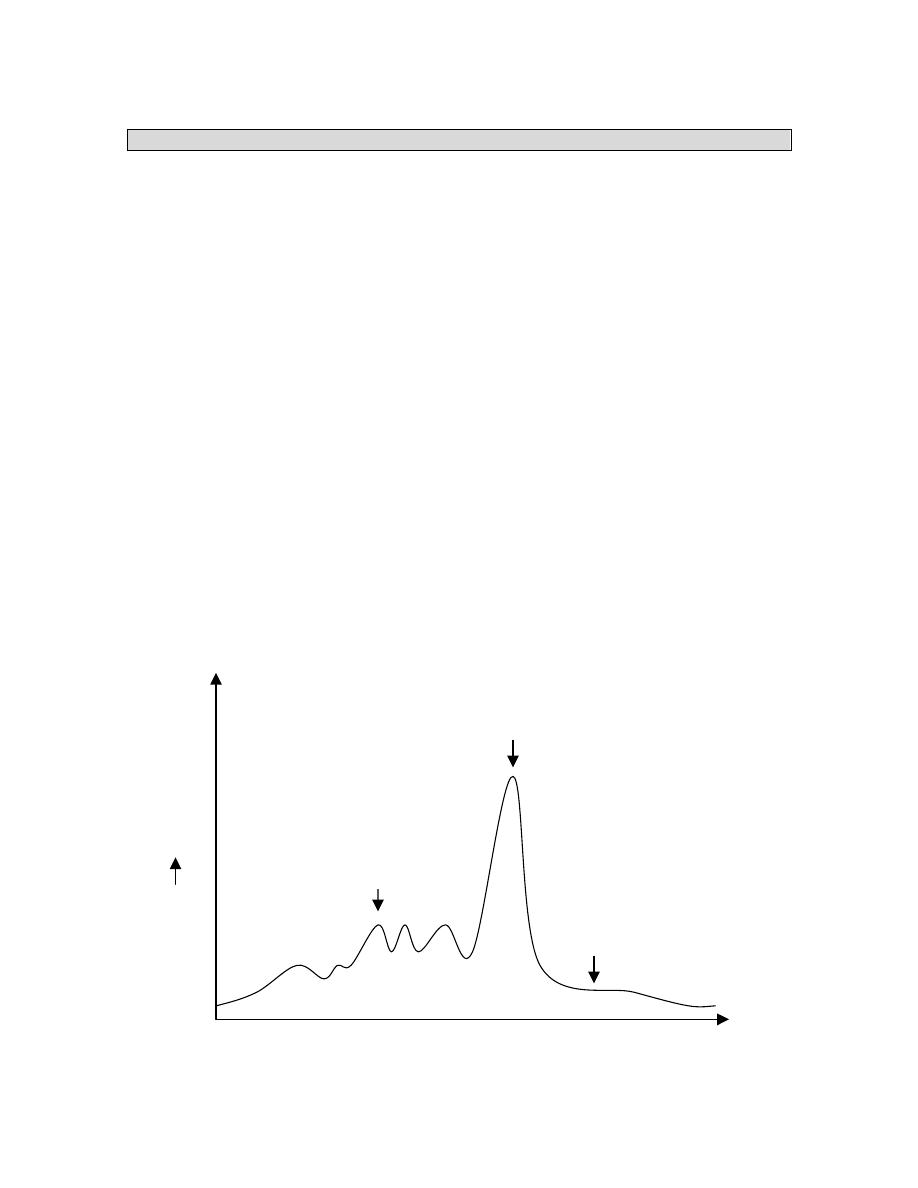

3 Biochemical Markers

i) Plasma

Proteins

OPTICAL

DENSITY

MIGRATION DISTANCE

Transferrin

8 day ½ life

Albumin

20 day ½ life

Transthyretin

Pre albumin

2 day ½ life

6

Serum Albumin Concentration: Good Predictor of Outcome, Poor Marker for

Nutrition Status

Serum albumin is an exceedingly poor indicator of nutrition status because it is very

insensitive and nonspecific. Infections and other inflammatory conditions which elevate

inflammatory cytokines cause a decrease in albumin synthesis and also cause capillary

leak resulting in an increased volume of distribution of albumin. Consequently, in sepsis

and burns, serum albumin concentration may decrease, more than 1 g/dl in 24 hours. In

contrast to its poor performance as an indicator of nutrition status, many studies have

documented that serum albumin concentration is a good predictor of morbidity and

mortality in many conditions.

Serum Proteins and Nutrition Status

Serum (visceral) proteins with a short half-life such as transferrin (8 days) and

transthyretin (prealbumin) (2 days) respond more quickly to declining or improving

nutrition status than does albumin, which has a half-life of 20 days. However, all three

are negative acute phase reactants, that is, the serum levels decrease rapidly when

catabolic inflammatory cytokines are released by infection or trauma. Also, the

transferrin level is increased by iron deficiency while the transthyretin level is increased

by renal failure and decreased by vitamin A deficiency. If these confounding factors are

kept in mind, transthyretin measurements and to a lesser extent transferrin measurements,

can be useful tools for assessing nutrition status. An undernourished patient with low

serum transthyretin will show a significant increase in transthyretin concentration after as

little as one week of adequate protein and calorie intake. Note: the quantity of

transthyretin in normal serum is too small to produce a distinct protein peak on serum

protein electrophoresis.

Fibronectin: opsonic glycoprotein (mw 440 000). Depletion correlates with

reticuloendothelial phagocyte clearance depression.

Creatinine - Height Index: is the ratio of 24 hour urine creatinine excreted compared

with height matched controls of the same sex. Expressed as a % and an index of 100%

indicates normal muscle mass, provided there is normal excretion of creatinine.

Immunological Markers: Total lymphocyte count < 1500 cells/pJ associated with

severe malnutrition. Clinical trials suggest that impaired delayed cutaneous

hypersensitivity is present in severe malnutrition and with poor clinical outcome.

Indirect Calorimetry and body composition analysis: are helpful when nutritional

requirements are difficult to estimate. Routine use cannot be advocated because they are

expensive, technically demanding, and not demonstrated to effectively predict clinical

outcome.

7

Multifactorial Prognostic Indices

a. Prognostic Nutritional Index: uses serum albumin and transferrin levels TSF and

delayed hypersensitivity skin test reactivity to predict the risk of operative morbidity and

mortality in relation to nutrition status. PNI 50% indicates high risk patients.

b. Prognostic Inflammatory & Nutritional Index: uses markers of inflammatory response

ie a - 1 acid glycoprotein & c-reactive protein, in combination with nutrition assessment

parameters (alb. & prealb.) to predict infectious complications and death.

c. Nutritional risk index: used in Veterans - Administration - cooperative group study of

preoperative morbidity and mortality using serum albumin and the ratio of current weight

to usual weight.

Dynamic Nutritional Assessment

Predictors of Poor Clinical Outcome

A number of measures initially designed and used to assess nutrition status correlate with

outcome for patients in acute hospitals and chronic healthcare institutions. However, it

remains unknown how much, if any, of the correlation between the measurements and

outcomes is a result of nutrition status as opposed to severity of illness or other factors.

The Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI) % = 158 - 16.8 (ALB) - 0.78 (TSF)- 0.20 TFN -

5.8 DH where PNI is an estimate of postoperative risk of complication, ALB is serum

albumin concentration (g/100 ml), TSF is triceps skinfold thickness (mm), TFN is serum

transferrin concentration (g/100 ml) and DH is delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity to any

of three recall antigens (0, nonreactive:

1, =5 mm induration: 2, > 5 mm induration).

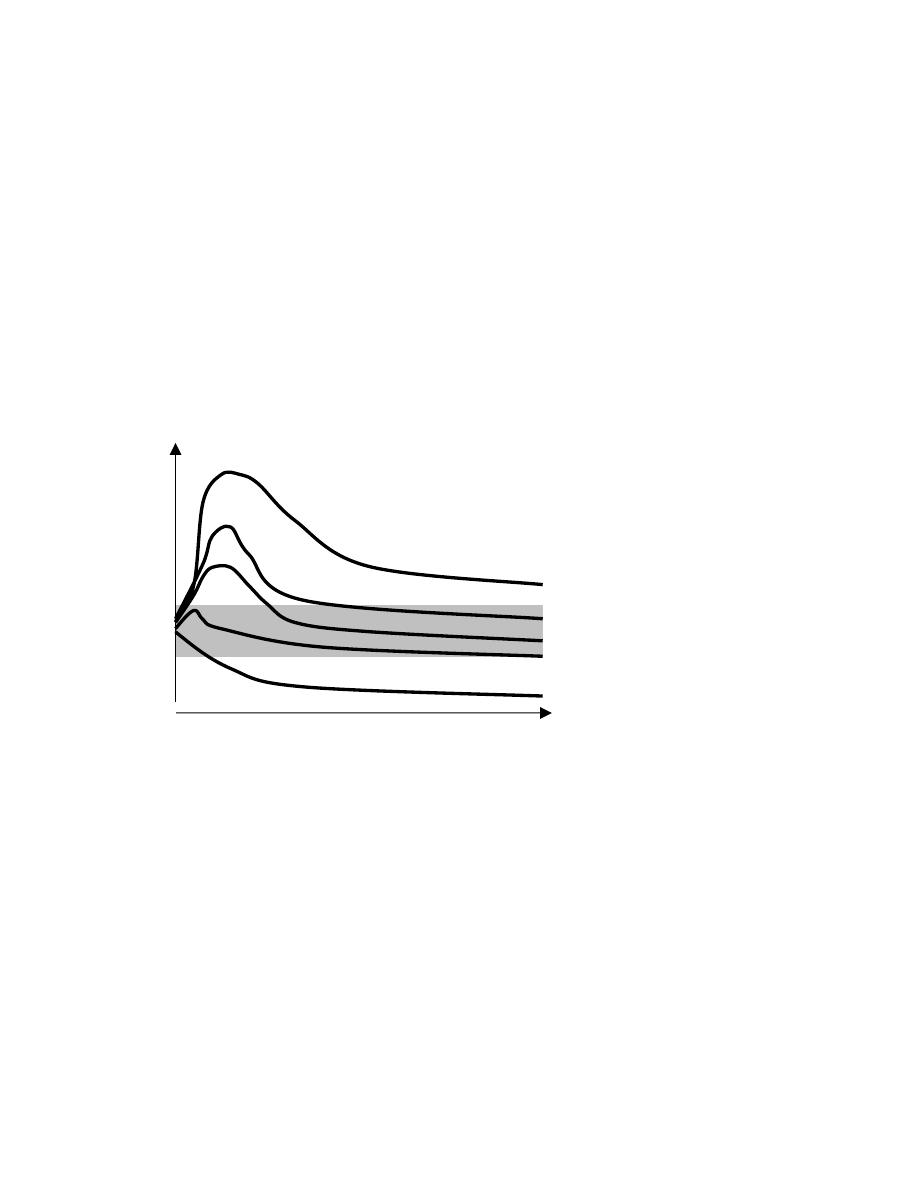

Major burn

Sepsis

Skeletal trauma

Elec. op

Starvation

0

25

50

Days

Resting

Energy

Expenditure

% of normal

50%

200%

8

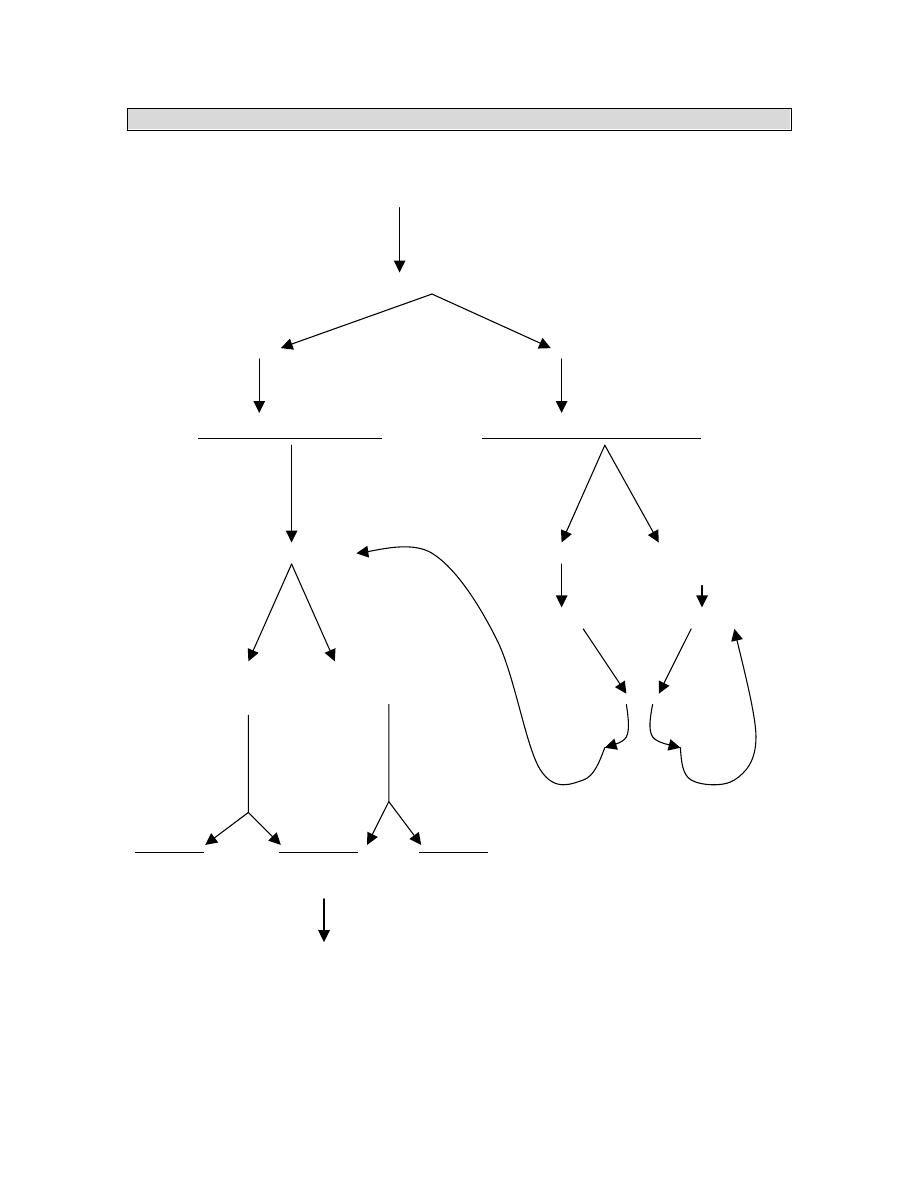

NUTRITIONAL SUPPORT

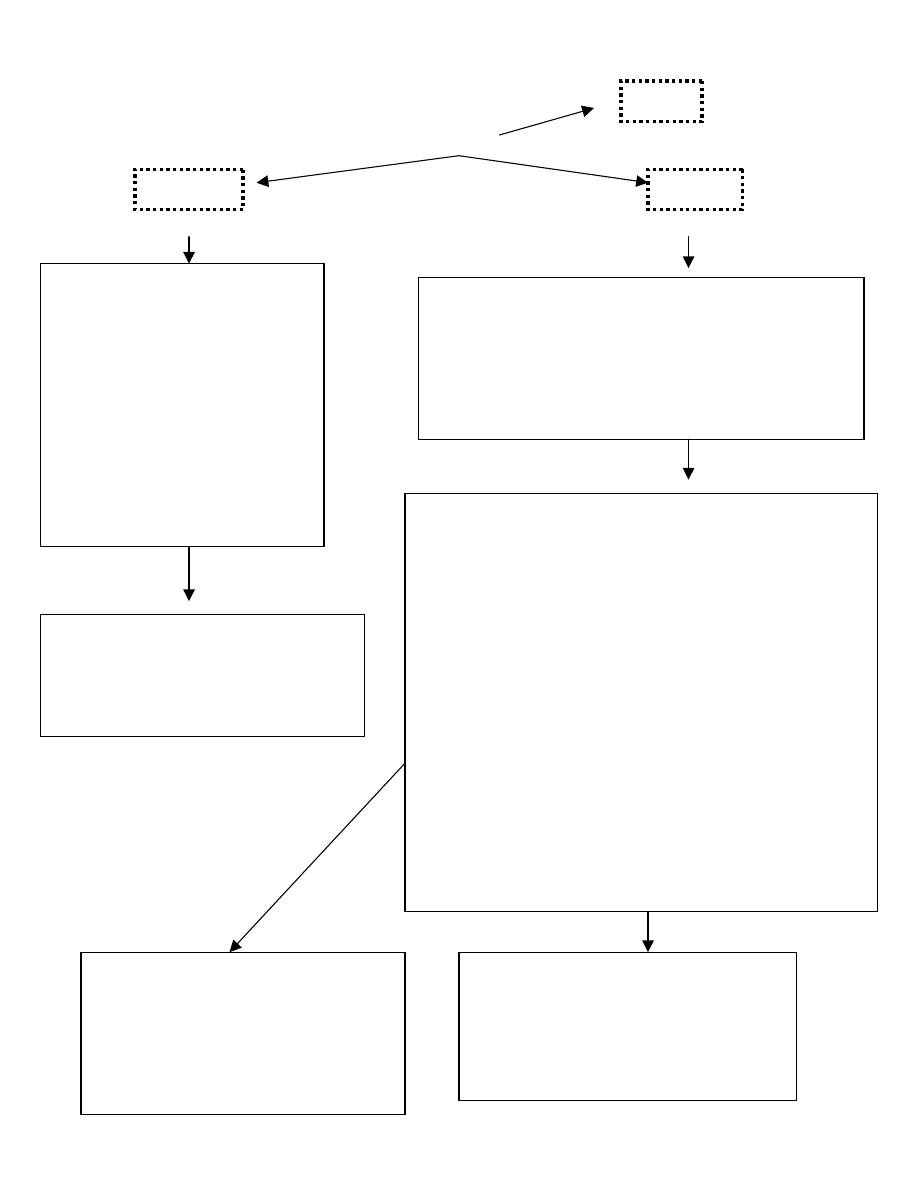

ROUTES TO DELIVER NUTRITIONAL SUPPORT

Nutrition assessment

Decision to initiate specialised nutrition support

FUNCTIONAL GI TRACT

YES NO (Obstruction, peritonitis,

intractable vomiting, acute

pancreatitis, short bowel

syndrome, ileus)

ENTERAL NUTRITION PARENTERAL NUTRITION

Long term Short term

Gastrostomy Nasogastric

Jejunostomy Nsoduodenal

Nasojejunal

GI Function Short term Long term or

fluid restriction.

Normal Compromised Peripheral PN

*

Central; PN

*

Intact Defined

Nutrients

3

formula

2

GI function returns

YES NO

NUTRIENT

TOLERANCE

Adequate

Inadequate

Adequate

Progress

PN

Progress to more

to oral feedings Supplementation complex diet and oral

Feedings

as

tolerated

Progress to total

Enteral feedings

9

Enteral vs. Parenteral

Compared to parenteral nutrition, enteral nutrition is less costly and has a more complete

nutrient profile. The complication rate, including the likelihood of infection, is probably

less for enteral than for parenteral nutrition although that is not well documented. On the

other hand, parenteral nutrition is easier to administer, better accepted by patients, and

provides more reliable delivery of nutrients. Taken together, the benefits of enteral

nutrition outweigh those of parenteral when both are possible.

ENTERAL NUTRITION

ADVANTAGES

1. Maintains git integrity and positive effect on immunity of small intestine

2. Enhanced utilization of nutrients

3. More efficient plasma insulin response

4. Ease and safety of administration

5. Less cost than TPN

6. Mechanical, infectious and metabolic complications less severe than with TPN.

INDICATIONS

Any condition which requires nutritional support and in which the GIT is functional.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

1. Generalized

peritonitis

2. Shock

3. Complete intestinal obstruction

4. Intractable vomiting/severe diarrhoea

5. Paralytic

ileus

6. Severe git bleeding

7. High

output

fistula

8. Early stages of short bowel syndrome

9. Acute severe pancreatitis.

Short-term supplementation

These are patients in whom the anticipated need for nutritional support is for a relatively

short period, often less than 6 weeks. A variety of commercially available feeding tubes

can be used to access the stomach or small intestine. For patient comfort, soft small bore

(7 to 9 French) tubes should be used. These tubes may be placed nasogastrically if

adequate gastric emptying and an intact gag reflex is present. They may also be placed

nasoenterically in patients with a higher risk of aspiration

10

Long-term supplementation

Patients in whom the anticipated need for nutritional support is greater than 6 weeks may

benefit from more permanent enteral access.

Gastrostomy tubes may be placed either operatively or percutaneously with endoscopic

guidance.

This route of feeding requires that gastric emptying is present and is contraindicated by

evidence of gastroesophageal reflux and absence of a gag reflex. One advantage of a

gastrostomy tube is that feedings may be administered either continuously or as

intermittent boluses, thus potentially simplifying care, especially in the outpatient setting.

Jejunostomy tubes are commonly placed operatively, either via laparotomy or with

laparoscopic assistance. They may either be permanent (end Roux-en-Y type) or

temporary (Witzel).

In selected cases, a jejunostomy may be placed endoscopically or using the needle

catheter technique. A small bore feeding tube may also be passed through an existing

gastrostomy tube to create a functional jejunostomy. Jejunostomy feedings are given

continuously, rather than as boluses.

Complications Of Enteral Nutrition

17

1. Gastro-intestinal : diarrhoea, vomiting, bloating, abdominal cramps.

2. Metabolic : glucose intolerance, excess CO

2

production, electrolyte

imbalances

3. Mechanical : Blocked tube, tube dislodgement, nasopharyngeal discomfort,

nasal erosions and necrosis (esp. children)

Complications of surgery ( gastrostomy; jejunostomy)

Perforation

Haemorrhage

Wound

infection

Bowel

obstruction/necrosis

Stomal

leakage

4. Infections : Aspiration pneumonia,

contaminated feeds - gastroenteritis

11

Principles Of Administration

1. Choosing the appropriate feed.

2. Most patients tolerate a polymeric feed.

3. In the presence of malabsorption - semi elemental formula used. Single nutrient

deficiencies - modular feed used.

4. Rate of administration: start slowly (approx. 20ml/hr) and increase to 80ml/hr within

48hrs. If poorly tolerated, reduce rate or discontinue feed and recommence slowly

once mechanical obstruction excluded.

5. Early feeding ( 48 hrs) has shown to prevent gut mucosal atrophy, peserve mucosal

integrity - reduced bacterial and endotoxin translocation, ensure maintenance of

normal gut flora - reduces gram negative proliferation and improves the status of the

gut immune system.

Products

Many formulas have been developed for enteral supplementation. These vary in

osmolarity, caloric content, protein complexity and density, and fat content. Typical

formulas contain 1 to 2 kcal/ml and between 30 and 60 g of protein per liter

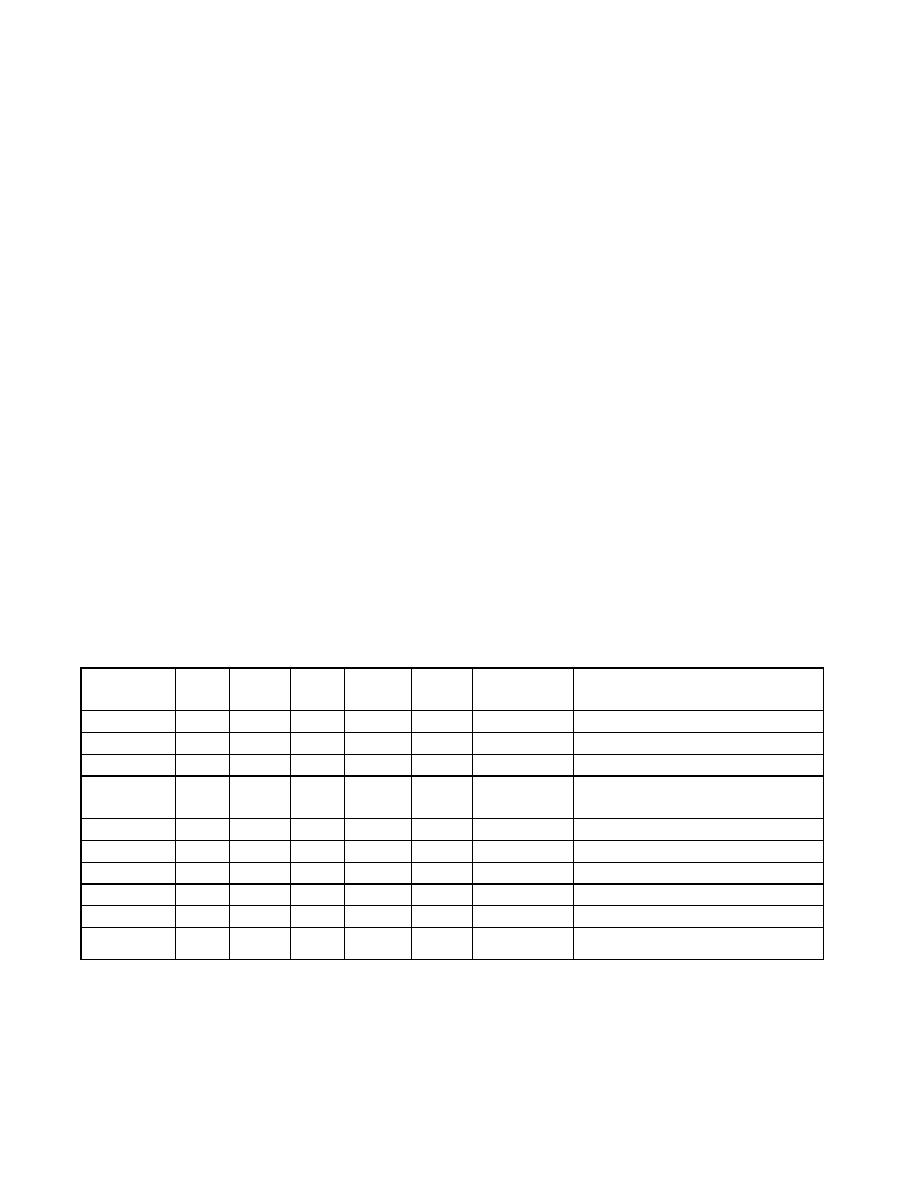

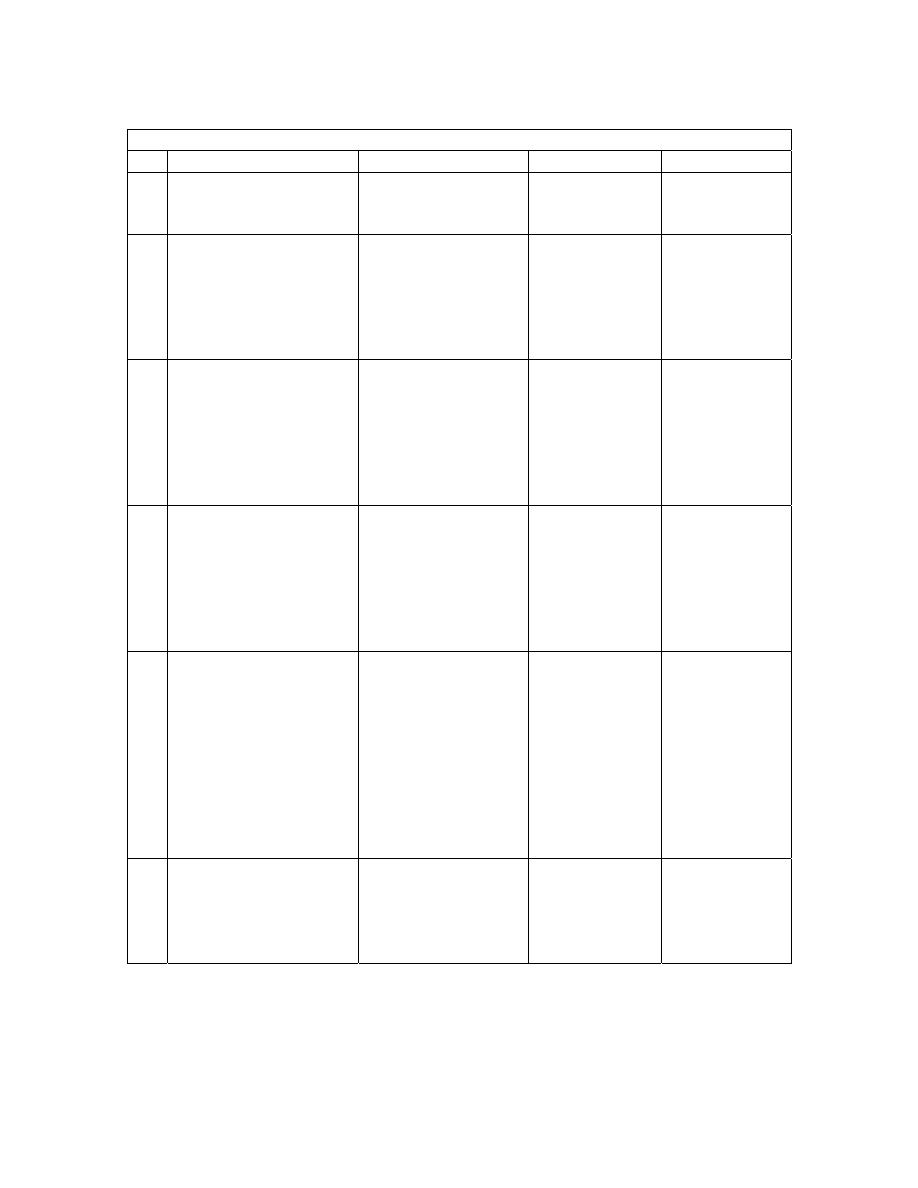

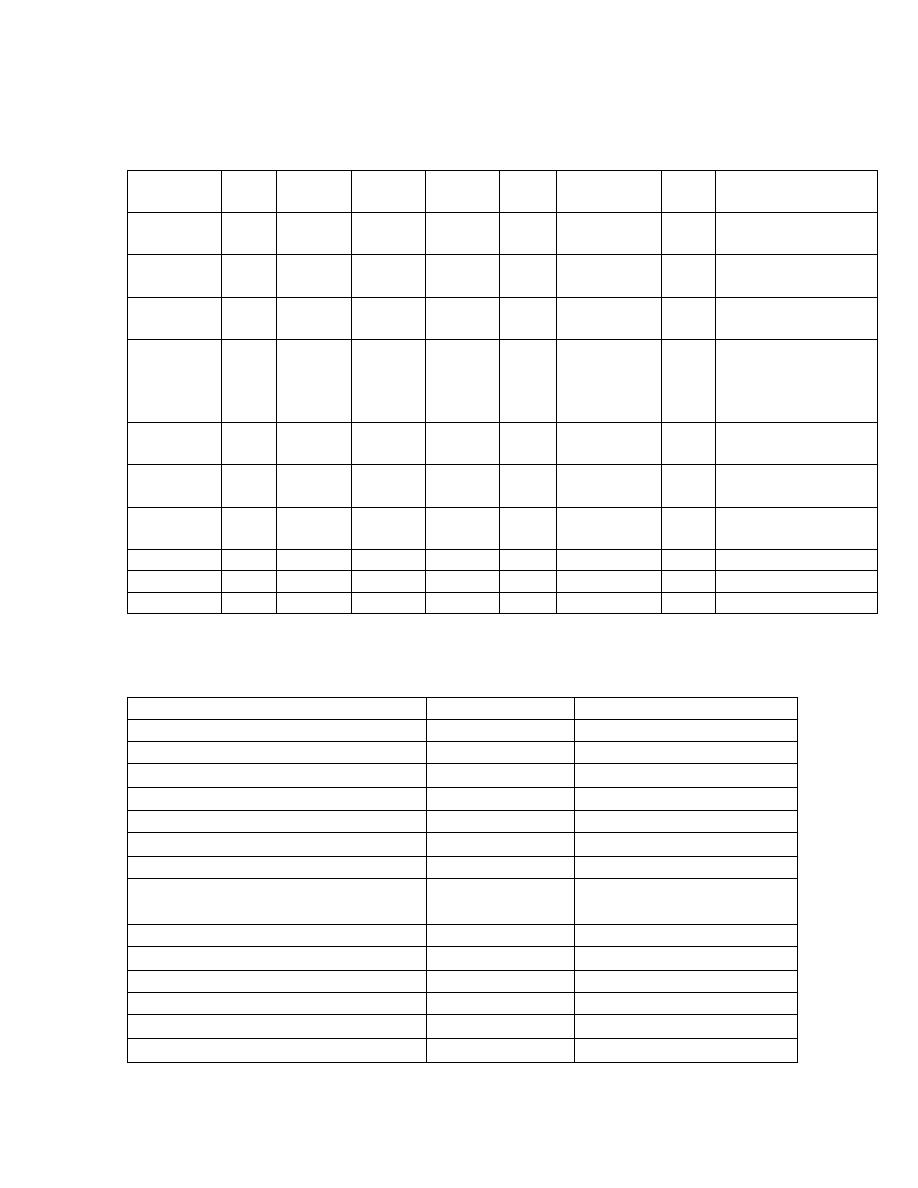

COMMERCIALLY AVAILABLE PRODUCTS

Formulae

(1000ml)

Kcal CHO

(g)

FAT

(g)

PROT

(g)

Kcal:

gN

OSM

mosmol/kg

USE

Ensure 1100

162

37,2

39,7

150:1

480

Osmolite 1060

145 37,6 37,2 178:1

300

Nutrison 1000

122,5

38,9

40

131:1

290

Alitraq

1000 165

15,5 52,5

120:1 575

Impaired GI function. Rich in

Glutamine (27g/100g)

Jevity 1060

151,7

35,9

44,4

150:1

300

Paediasure 1000 109,7 49,7 30

208:1 310

Peptison 1000

187,5

10 40

131:1

470

Glucerna 1000

33,3 50 16,7 150:1

375

Suplena 2000

255,2

95,6

30 418:1

600

Advera 1280

215,8

22,8

60 133:1

680

12

Early Enteral Feeding

A compelling clinical and scientific rationale appears to support the use of enteral feeding

as opposed to bowel rest or total parenteral nutrition (TPN) in patients after trauma,

including major surgery.

1. Aggressive early enteral feeding has been shown to decrease sepsis and improve

outcome in critically ill patients after major trauma.

2. In individual studies and in meta-analysis, patients fed via total enteral nutrition

(TEN) after abdominal surgery for trauma experienced fewer septic complications

than patients fed via the parenteral route.

3. Third, the use of perioperative TPN in the perioperative period is highly

controversial, with several studies reporting an increase in infective complications

in subsets of patients.

4. The cost of TEN is considerably less than TPN.

Immuno modulating drugs

(Discussed later under Management of the critically ill patient)

OXEPA

OXEPA is a low-carbohydrate, calorically dense enteral nutrition product designed for

the dietary management of critically ill patients on mechanical ventilation. It contains

eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) (from sardine oil), gamma-linolenic acid (GLA) (from

borage oil), and antioxidants. OXEPA can be used as a sole source of nutrition for tube

feeding.

•

For critically ill patients on mechanical ventilation

•

For critically ill patients with LUNG INJURY, such as: pneumonia; sepsis; chest

injury; multiple trauma; burns; shock and hypoperfusion; aspiration or near-

drowning; cardiopulmonary bypass; or hyperfusion-associated lung injury.

13

Features :

•

Complete, balanced nutrition for tube-feeding patients

•

Unique patented oil blend-contains EPA from sardine oil and GLA from borage

oil

•

Contains 25% of fat as MCTs for improved fat absorption

•

Fortified with elevated levels of the antioxidants all-natural vitamin E, beta-

carotene, and vitamin C

•

1.5 Cal/mL, 355 Cal/8 fl oz, and a moderate osmolality of 493 mosm/kg H20

•

Caloric density is high to minimize the volume required to meet energy needs

•

Meets 100% of RDI for 24 key vitamins and minerals in 1420 Calories

(four 8-fl-oz cans)

•

Lactose- and gluten-free

PARENTERAL NUTRITION

If enteral nutrition is not possible in the malnourished or at-risk patient, the parenteral

route must be utilized. Parenteral nutrition may be used for either primary or supportive

therapy

Indications for Parenteral Nutrition

Primary therapy

Gastrointestinal fistula

Short bowel syndrome

Acute renal failure

Hepatic insufficiency

Inflammatory bowel disease Efficacy not established

Secondary therapy

Radiation enteritis/chemotherapy toxicity

Hyperemesis gravidarum

Prolonged ileus

Preoperative therapy

Efficacy not established

Cardiac cachexia

Efficacy not established

Pancreatitis insufficiency

Efficacy not established

Cancer

Efficacy not established

Sepsis

Efficacy not established

14

TPN Formula Composition

Components of TPN include dextrose; lipids; amino acids; electrolytes including

phosphorus, potassium, sodium, magnesium, calcium, chloride, and acetate; vitamins and

trace elements.

Typical vitamin amounts administered daily in TPN are:

vitamin A 3,300 IU, vitamin D 200 IU, ascorbic acid 100 mg, folic acid 400 mcg, niacin

40 mg, riboflavin 3.6 mg, thiamin 3 mg, pyridoxine 4 mg, cyanocobalamin 5 mcg,

pantothenic acid 15 mg, biotin 60 mcg, and vitamin E 10 IU.

These approximate amounts are present in commercial mixtures. Vitamin K 1 mg daily or

5-10 mg weekly is often added separately.

A typical trace element cocktail provides approximately the following per day: zinc

5 mg, copper 1 mg, manganese 500 mcg, chromium 10 mcg, and selenium 60 mcg.

Molybdenum may also be included.

NUTRIENT MIXTURES

Standard solutions

-

Peripheral - Vamin 750 ml + 20 % intralipid + fluids

-

Central - Synthamin 14 - 14g N2

-

Intralipid 10% - soybean oil + egg yolk phospholipids + glycerol 500mls.

-

Glucose 50% - 500mls.

-

Maintelyte - 10% glucose + electrolytes - 1

l

-

Soluvit - water soluble vitamins

-

Vitalipid - fat soluble vitamins

-

Addamel - essential micronutrients.

All mixed into 3

l bags.

15

Routes

800 mOsm/L range

2,000 mOsm/L range

Peripheral

Central

1. Needs good peripheral veins

2. Limited to 2 major veins

3. Sites have to be changed

every 24 hrs.

4. Prone to phlebitis if

osmolarity >900 mOsm/L

5. In order to provide adequate

calories in a reasonable

volume with a tolerable

osmolality, lipid provides

50% to 70% of the

nonprotein calories in

peripheral TPN

1. Usually via the infraclavicular route (subclavian

vein) using a silicone, double-lumen catheter.

2. strict aseptic conditions.

3. Occlusive

hydrocolloie dressings are most

suitable. The dressings and administration set

must be changed every third day.

Risk minimized by:

1. hydrocortisone to each litre of solution

2. adding 1% sodium bicarbonate

3. change site daily

4. run fluids over 12-16 hours

Complications Complications

Catheter related

(i)

Mechanical : central vein thrombosis, catheter

embolism, haemo-pneumo

thorax,

haemopericardium, air-embolism, tracheal

puncture, arterial laceration, brachial plexus

injury.

(ii)

Sepsis : Staphylococcus epidermidis,

candida albicans

(iii)

Blockage : Use of heparin and choice of

catheter (silicone/polyurethane)

Metabolic : Hyperglycaemia, electrolyte and acid

base

abnormalities,

trace

element

and vitamin deficiencies.

Electrolyte abnormalities

Hypoglycaemia

Hepatic function changes: Cholestasis, elevated

liver enzymes and hepatomegaly

GI changes

Atrophy of intestinal mucosa

PREVENTING HYPERGLYCAEMIA

Begin the infusion at 40 ml/h of 25 per

cent glucose based solution and

increasing the infusion rate by 20 ml/h

every 24 h, depending on glucose

tolerance.

PREVENTING TPN ASSOCIATED

LIVER DISEASE

Decrease dextrose content < 40 kcal/kg/day

Decrease fat content < 1 g / kg / day

Adequate protein intake < 1-1.5g/kg/day

PICC

16

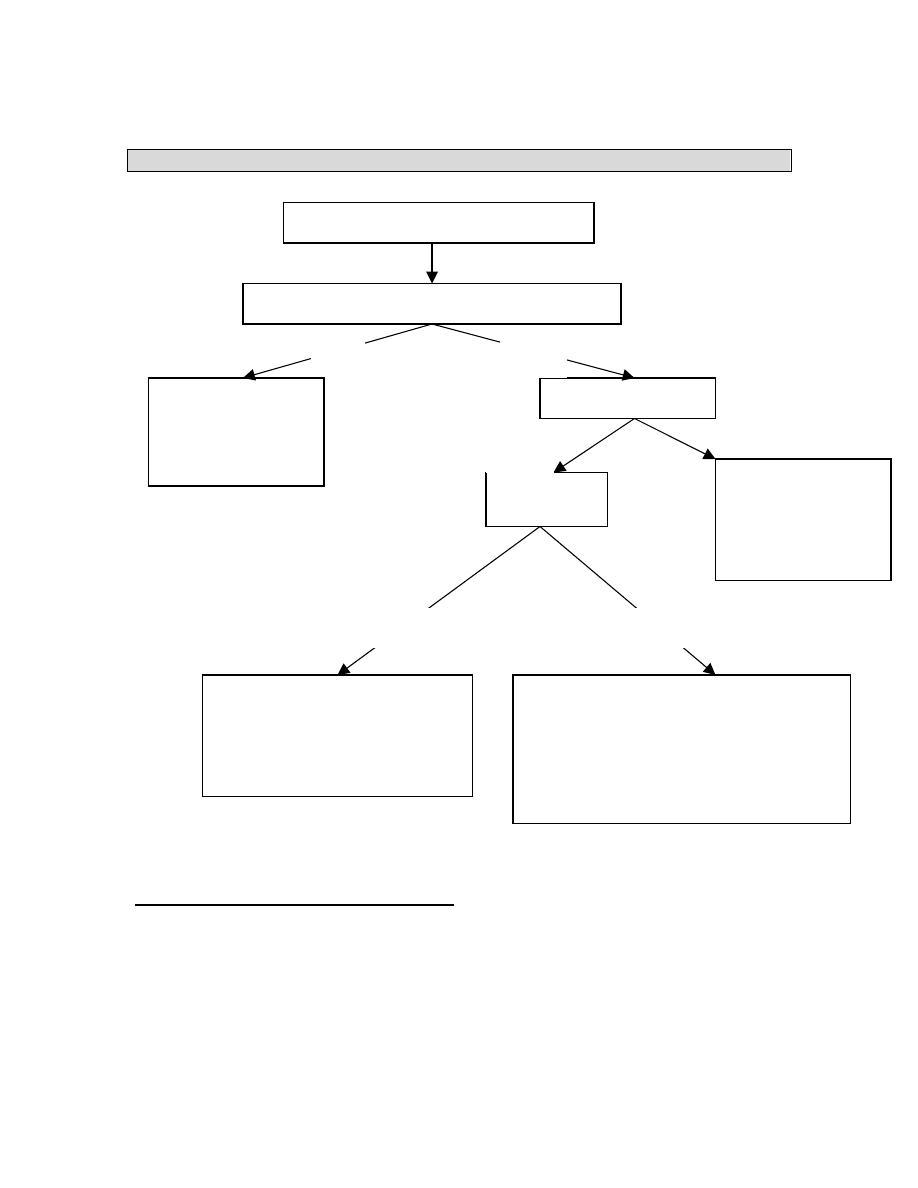

MANAGEMENT OF CATHETER RELATED SEPSIS

PICC (Peripherally inserted central line)

A cubital fossa PICC provides a safe effective means of administering intravenous

therapy.

A PICC can be expected to last two months without complication.

Complications that do occur are most likely in the first week.

The most common complication resulting in line removal was phlebitis.

Line-related sepsis is a very rare event.

Pyrexia > 38

°C / Swinging temperature

Does the patient still require nutritional support

Remove central line

catheter for culture

If pyrexia persists –

full septic screen.

Is the patient stable?

NO

YES

Stop TPN.

Resuscitate.

Broad spectrum

antibiotics.

Full septic screen

Check blood

cultures.

NO

YES

Remove central line (MCS)

Start PPN

Appropriate antibiotic.

Await 3 neg blood cultures before

reinserting CVP

Clinical evaluation to

exclude obvious source

eg intra-abdominal

sepsis (U/S or CT useful)

Full septic screen: Rail-road CVP – MCS

Body fluids / secretions – MCS

POSITIVE

NEGATIVE

17

This means that the PICC compares favourably with any other means of venous access

4

and is the method of choice for most intermediate or longer term intravenous therapy.

NUTRITIONAL SUPPORT IN CLINICALLY RELEVANT SITUATIONS

A. BURNS

• Appropriate nutritional support contribute significantly to improve patients survival.

• Helps to maintain body weight, promote wound healing, combat infection, preserve

body nutrient reserves and replace visceral and somatic proteins

• Early enteral nutrition route unless non-functioning gut → then parenteral nutrition.

• Carbohydrates 50%, protein 20% and lipid 30%.

• Recent evidence that omega-3-fatty acids results in increased feeding tolerance.

• Arginine supplementation improves CMI and wound healing and is a conditionally

indispensable a/acid for maintaining body protein homeostasis and nutrition in

severely burned patients.

B. PANCREATITIS

Estimating the severity of pancreatitis is important.

Most acute pancreatitis is mild, self-limiting and resolves within 5-7 days, hence no

need for nutritional support.

Severe pancreatitis induces a hypercatabolic state resulting in rapid weight loss and

increased morbidity and mortality.

Chronic pancreatitis results in malnutrition. Therefore the aim is to treat the

malnutrition and to avoid the development of malnutrition.

In severe pancreatitis the best route of nutrition is the nasojejunal feeding with a

semi-elemental low triglyceride diet. The outcome s are similar than those patients

receiving TPN. If enteral feeding increases pain. Ascites or fistula output then

discontinue.

Pancreatic fistula: Low output ----enteral feed

High output ---TPN

Pancreatic Ascites: TPN + somatostatin

C. ENTEROCUTANEOUS FISTULA

-

TPN has been shown to have no effect on mortality but does influence

closure as shown in local studies.

-

high output > 500 ml - TPN + somatostatin

-

definitive closure if no decrease in 6 weeks , patient afebrile.

-

Low output < 500 ml - enteral feed.

18

D. CRITICALLY ILL PATIENT

Have increased metabolic demands (20-60% above basal needs). Goal is to

maintain and not to replete. Initial /calorie delivery 25 Kcal/kg/day and 1.5-2.0g

protein/kg/day.

Associated complications

1. Hepatic

dysfunction

Aetiology : TPN, hepatic hypoperfusion, drug induced liver disease

Appropriate nutrition ( prevention of hepatic encephalopathy)

Reducing the gastro-intestinal protein load by restricting dietary protein

intake, preventing gastrointestinal bleeding, and encouraging intestinal

emptying with agents such as lactulose. In stage I and II encephalopathy,

protein intake should be restricted to fewer than 40 g/day, and this should

be further reduced to fewer than 20 g/day in patients with stage III and IV

encephalopathy. Caloric intake, preferably as dextrose, should be

maintained in excess of 2000 cal (8.4 kJ)/day. Patients with liver damage

may be lipid intolerant, and the presence of lipaemic serum requires a

reduction of lipid intake.

2. Acute pancreatitis (discussed above)

3. Stress ulcer prophylaxis : Critically ill surgical patients are at risk from

gastrointestinal stress ulceration. Ulcers are most often sited in the fundus of the

stomach or the first part of the duodenum. They are small, multiple, superficial,

well demarcated, and usually without surrounding oedema. Stress ulcer bleeding

is less common in patients who are receiving enteral nutrition; this could reflect a

lower severity of illness in view of the maintenance of gastrointestinal absorptive

function or be a direct protective effect of nutrients in the stomach and

gastrointestinal tract.

Immunonutrition :

Intended for critically ill patients at risk for infections and for use in the

immediate postoperative period. They contain increased protein,

immunostimulatory amino acids, and lipids, and may decrease infectious

complications.

Immune enhancing formulas include arginine, glutamine, nucleic acids and

omega-3 fatty acids.

L-arginine

and

I-glutamine: -

stimulates host defenses

- modulates

tumour

metabolism

19

- increases

wound

healing

- decreases

nitrogen

losses

after

trauma

L-Glutamine: - maintains integrity of intestinal barrier function in preventing

translocation of bacteria and endotoxins from bowel lumen into systemic

circulation. Combination of nutrients have shown to enhance host defences

significantly as reported by Cerr et al. Benefits of immunonutrition were

reduction in hospital stay and decrease infections but has no effect on

mortality as shown by Beale et al. In another study by Galban et al. has

shown a significant reduction in mortality in patients on Immunonutrition.

Essential Fatty Acids: Acts as an intracellular messenger and plays a

regulatory role in the metabolic process. Maintains cell structure and

function. Administered enterally or parenterally via central or peripheral vein.

Eg: Omega – 3 and Omega 6 fatty acids: enhances cell- mediated immunity

and has shown to improve histological appearance of IBD. Improves

immunocompetence, has antithrombotic effects which prolongs bleeding time.

Long and Medium Chain Triglycerides: a 50:50 mixture of LCT & MCT

has shown to have greater physiochemical stability. Resulting in more oxygen

radicals being produced LCT impairs the RES while MCT stimulates it. Has a

trophic effect on the bowel, reducing bile output and decrease the risk of

hepatic dysfunction.

Branched Chain Amino Acids: Leucine, isoleucine and valine metabolized

in skeletal muscle and are important oxidative fuels. Leucine rich amino acid

stimulates resting energy expendature and thermogenesis by up to 20%.

INTENSIVE INSULIN THERAPY

Hyperglycemia associated with insulin resistance is common

in critically ill patients, even

those who have not previously

had diabetes.

In diabetic patients

with acute myocardial infarction, therapy to maintain blood

glucose at

a level below 215 mg per deciliter (11.9 mmol per

liter) improves the long-term outcome.

In nondiabetic

patients with protracted critical illnesses, high serum levels

of insulin-like

growth factor–binding protein 1, which

reflect an impaired response of hepatocytes to

insulin, increase

the risk of death.

In a study by

Van den Berghe et al,

2001 showed that intensive insulin therapy to

maintain blood glucose at or below 110 mg per deciliter reduces morbidity and mortality

among critically ill patients in the surgical intensive care unit.

20

1. HEAD INJURY PATIENTS

-

The metabolic response to trauma is usually a sustained hypermetabolic state

with a peak hormonometabolic response at 3 - 5 days.

-

The exact mechanisms involved are unknown with the following postulates :

a. Damage to the cardioregulatory pons with autonomic hyperactivity and

increased catecholamines release.

b. Damage to the blood brain barrier with resultant catecholamine accumulation.

c. Steroid therapy .

d. Raised intracranial pressure may result in gastric hypersecretion.

This effectively leads to a basal metabolic rate that may be up to 140% of

normal. Nitrogen excretion may be increased up to 7 times which depends on

intake , muscle mass , muscle use and steroid therapy. Hyperglycaemia develops due

to the mechanisms mentioned and the overall response to trauma. This tends to

produce and worsen intracellular lactic acidosis , may result in increased pCO2

with further increase in intracranial pressure.

Requirements :

i)

40 - 50 kcal/kg/day , indirect calorimetry is the standard for determining the

requirements.

ii)

protein 1,5 - 2,0 g/kg/day although levels of 2 - 2,5 g/kg/day are now being

given.

iii)

The caloric needs are the basal energy expenditure multiplied by 1,4

iv)

Non protein energy : nitrogen is 80 : 1 initially then up to 130 : 1.

Route : enteral feeds should be aimed for early on ie within 48 hrs.

Other options include percutaneous endoscopic jejunstomy or gastrostomy

with long term requirements.

The standard indications for parentral therapy apply.

SHORT BOWEL SYNDROME

A number of conditions require surgical resection or bypass of intestine resulting in a

short bowel. The pathophysiologic consequence of a short bowel is malabsorption.

Malabsorption due to a short bowel and its clinical consequences is referred to as the

short bowel syndrome. Severity is determined by the amount of intestine resected, the

site resected and the ability of the intestine to undergo adaptive hyperplasia. A short

bowel is one of the causes of intestinal failure.

Other causes of intestinal failure include motility disorders (visceral myopathy, visceral

neuropathy, scleroderma, amyloidosis), refractory celiac disease and radiation enteritis.

In adults, the length of the small intestine when measured at autopsies is on average 600

cm (20 feet). The length of the colon is about 150 cm (5 feet). There is no anatomic

distinction that demarcates jejunum from ileum. The proximal 2/5 of small intestine is

21

usually accepted as jejunum and the distal 3/5 as ileum. Most dietary carbohydrates, fats,

proteins, vitamins, minerals, and trace elements are absorbed within the first 2/3 of the

small intestine.

Most iron is absorbed in the duodenum; folate in the proximal jejunum. Vitamin B12

(cobalamin) and bile salts are only absorbed in the distal ileum. Water and electrolytes

are absorbed throughout the small intestine and colon. A small amount of carbohydrate

escapes absorption in the small bowel and enters the colon. This is important for colonic

health. Bacteria in the colon metabolize carbohydrate, soluble fiber and some

unabsorbed fats to short chain fatty acids which are the preferred energy source for

colonocytes. Short chain fatty acids are absorbed in the colon along with sodium and

water, thus promoting caloric salvage and fluid absorption.

Small feedings should be started as soon as possible because nutrients are important in

stimulating adaptive hyperplasia in the intestine. Only a small amount of calories (about

500-750 kcal of a soft normal diet) should be given orally to start and then increased as

tolerated. Oral fluids should be limited and given separately from food. Feeding

stimulates digestive juices and may increase intestinal fluid losses. Intestinal fluid and

electrolyte losses should be measured and replaced daily.

There are a number of ways to enhance calorie absorption for optimal weight in those

with a short bowel. Frequent small meals and slowing transit enhances absorption by

maximizing the contact time for nutrient absorption. Medium chain triglycerides

(MCTs)are water soluble and can diffuse across the epithelium intact or as medium chain

fatty acids. Administration of excess amounts of MCTs should be avoided because

unabsorbed MCTs in the intestinal lumen cause an osmotic diarrhea. In those with >100

cm of ileum resected, exogenous bile salts (e.g. ox bile, cholylsarcosine) improves fat

absorption; ursodeoxycholic acid does not.

CONCLUSION

Nutritional support of the surgical patient is an extremely important part of the total care

of the patient, unfortunately in our hospital setting it is given little importance to the

average patient and only reserved for the acutely ill patient. Early assessment of the

patient and initiation of nutritional support will yield excellent results and reduce

morbidity and mortality.

22

REFERENCES

1. Haffejee AA . Surgical nutrition in Mieny and Mennen eds. Principles of

Surgical Patient care. Pretoria Academica 1990 : 1 - 16.

2. Van den Berghe M.D., Ph.D., Pieter Wouters, M.Sc., Frank Weekers, M.D., Charles

Verwaest . Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill patient. NEJM 2001; 345 :

1359 – 67.

3. Downs JH , Haffejee AA . Nutritional assessment in the Critically Ill . Curr

Opinion Clin. Nutr. Metabolic Care 1990 ; 1 : 275 - 279.

4. Griffiths R D. Glutamine enriched TPN formula. Nutrition 1997; 13 : 295 – 302.

5. Bissetty T V. Nutritional support of the Surgical patient. Surgical Seminar 2003.

6. Naidoo R . Nutritional support of the Surgical patient. Surgical Seminar 2001.

7. Alli MO. Nutritional support of the Surgical patient. Surgical Seminar 1999.

8. Moodley S. Nutritional support of the Surgical patient. Surgical seminar 1997.

9. Alan L. Miller, ND Therapeutic Considerations of L-Glutamine: A Review of the

Literature. Glutamine physiology, biochemistry, and nutrition in critical illness.

Austin, TX: R.G. Landes Co.; 1992.

10. ASPEN Board of Directors . Rationale of Adult nutritional support guidelines.

JPEN 1993 ; 17 ( 4 ) : 58 - 68.

11. Jeejeebhoy K , Detsky A . Assessment of nutritional status. JPEN 1990 ;14

(supplemental ) :193 -195.

12. Klein S , Kinney J . Nutrition support in clinical practise : review of published

data and recommendations for future research directions. JPEN 1997 ; 21 ( 3 ) :

133 - 155.

13. Gibbs J , Cull W. Pre - operative albumin as a predictor of operative mortality

and morbidity. Arch Surg 1999 ; 134 : 36 - 42.

14. Tellado - Rodrigues J , Garcia J. Nae / Ke Ratio is a better indicator of

nutritional status than standard anthropometric and biochemical indices. Surg

Forum 1988 ; 38 : 56 - 58.

15. Sacks G , Poole G. Continuous versus intermittent nasogastric enteral feeding in

trauma patients. JPEN 2000 ; 24 ( 1 ) : 15 - 20.

16. Kealer A , Swails W. Early enteral feeding in post surgical cancer patients.

Ann Surg 1996 ; 223 ( 3 ) : 316 - 333.

17. Ling E , Caro C. Randomised trial of safety and efficacy of immediate post

operative enteral feeding in patients undergoing gastrointestinal resection. BMJ

1996 ; 312 ( 6 ) : 332 - 335.

18. Payne J , Whanwaya H. First choice for TPN : the peripheral route. JPEN 1993 ;

17 ( 5 ) : 468 - 478.

19. Alexander WJ. Immunoenhancement via enteral nutrition. Arch Surg 1993 ; 128

: 1242 - 1244.

20. Berard MP , Zazzo JF. Total parentral nutrition enriched with arginine and

glutamate generates glutamine and limits protein catabolism in surgical patients

hospitalized in intensive care units. Crit Care Med 2000 ; 28 ( 11 ) : 3637 - 3644.

21. Wu Y , Fukatsu K. Glutamine enriched TPN maintains intestinal IL 4 and

mucosal IgA. JPEN 2000 ; 24 ( 1 ) : 46 - 52.

23

22. Loughran S , Hataneka T. Leucine rich amino acid solution prevents operative

hypothermia under general anaesthesia. JPEN 2000 ; 24 ( 1 ) : 67 - 69.

23. Heys SD , Gardner E. Nutrients and the surgical patient : current and potential

therapeutic applications to clinical practise. J R Coll Surg Edin 1999 ; 44 : 283

- 293.

24. Driscoll DF , Bacon MN. Physicochemical stability of 2 types of IV lipid

emulsion as total nutrient admixture. JPEN 2000 ; 24 ( 1 ) : 15 - 22.

25. Naber A , Kruimel I. With MCT , higher and faster oxygen radical production

by stimulated polymorphs occurs. JPEN 2000 ; 24 ( 2 ) : 107 - 112.

26. Rothstein R , Rombeau J. Nutrient pharmacotherapy for gut mucosal diseases.

Gastroenterology clinics N America 1998 ; 27 ( 22 ) : 387 - 399.

27. Kalfarentzos F , Kehagias J. Enteral versus parentral nutrition in acute

pancreatitis. BJS 1997 ; 84 : 1665 - 1669.

28. Lob D , Naemon A. Evolution of nutritional support in acute pancreatitis. BJS

2000 ; 87 : 695 - 707.

29. Madiba TE , Haffejee AA. Nutritional support in the management of external

pancreatic fistulas. SAJS 1995 ; 33 ( 2 ) : 81 - 84.

30. Norton J , Linda G. Intolerance to enteral feeding in brain injured patients. J

Neurosurg 1988 ; 68 : 62 - 66.

31. Borzotta A , Paxton J. Enteral versus parentral nutrition after severe closed

head injury. J Trauma 1994 ; 37 ( 3 ) : 459 - 468.

32. Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Drover JW, Gramlich L, Dodek P, and the Canadian

Critical Care Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee. Canadian clinical practice

guidelines for nutrition support in mechanically ventilated, critically ill adult patients.

JPEN. 2003;27:355-373.

24

APPENDIX

KING EDWARD VIII HOSPITAL (ICU) ENTERAL FEEDING PROTOCOL

Protocol 1

Protocol 2

Protocol 3

Protocol 4

Haemodynamically

stable

Hypoalbinaemia Diarrhoea

/

intolerance

Diabetic/

glucose

intolerance

Day 1

Jevity (500 ml) 20ml/hr

Protein = 22,2g

energy = 530Kcal

Jevity (500ml)

20ml/hr

Protein = 22,2g

Energy = 1060 Kcal

Jevity (500ml)

20ml/hr

Protein = 22,2g

Energy = 1060

Kcal

Jevity (500ml)

20ml/hr

Protein = 22,2g

Energy = 1060

Kcal

Day 2

Jevity (1000ml)

40ml/hr

Protein = 44,3g

Energy 1060Kcal

Jevity (1000ml)

40ml/hr

Protein = 44,3g

Energy = 1060 Kcal

Jevity (1000ml)

40ml/hr

Protein = 44,3g

Energy = 1060

Kcal

Jevity

(1000ml)

40ml/hr

Protein = 44,3g

Energy = 1060

Kcal

Day 3

Jevity (1500ml)

60ml/hr

Protein = 66,5g

Energy 1590Kcal

Jevity (1500ml)

60ml/hr

Protein = 66,5g

Energy = 1590 Kcal

Jevity (1500ml)

60ml/hr

Protein = 66,5g

Energy = 1590

Kcal

Jevity

(1500ml)

60ml/hr

Protein = 66,5g

Energy = 1590

Kcal

Day 4

Jevity (2000 ml) 80 ml /

hr

Protein – 88,6g

Energy 2120Kcal

IL Jevity + IL Jevity

plus 80ml/hr

Protein = 99,8g

Energy = 2260 Kcal

or for poor wound

healing operative 60

ml/hr

Protein = 99,9g

Energy = 1950 Kcal

Jevity (2000

ml) 80 ml / hr

Protein – 88,6g

Energy

2120Kcal

Jevity (2000

ml) 80 ml / hr

Protein – 88,6g

Energy

2120Kcal

Long term

As above

Once nutritionally

repleted, return to

jevity 2L/day

(80ml/hr)

If still poor

tolerance, try

pepttsorb

(semi-elemental

feed)

As above

25

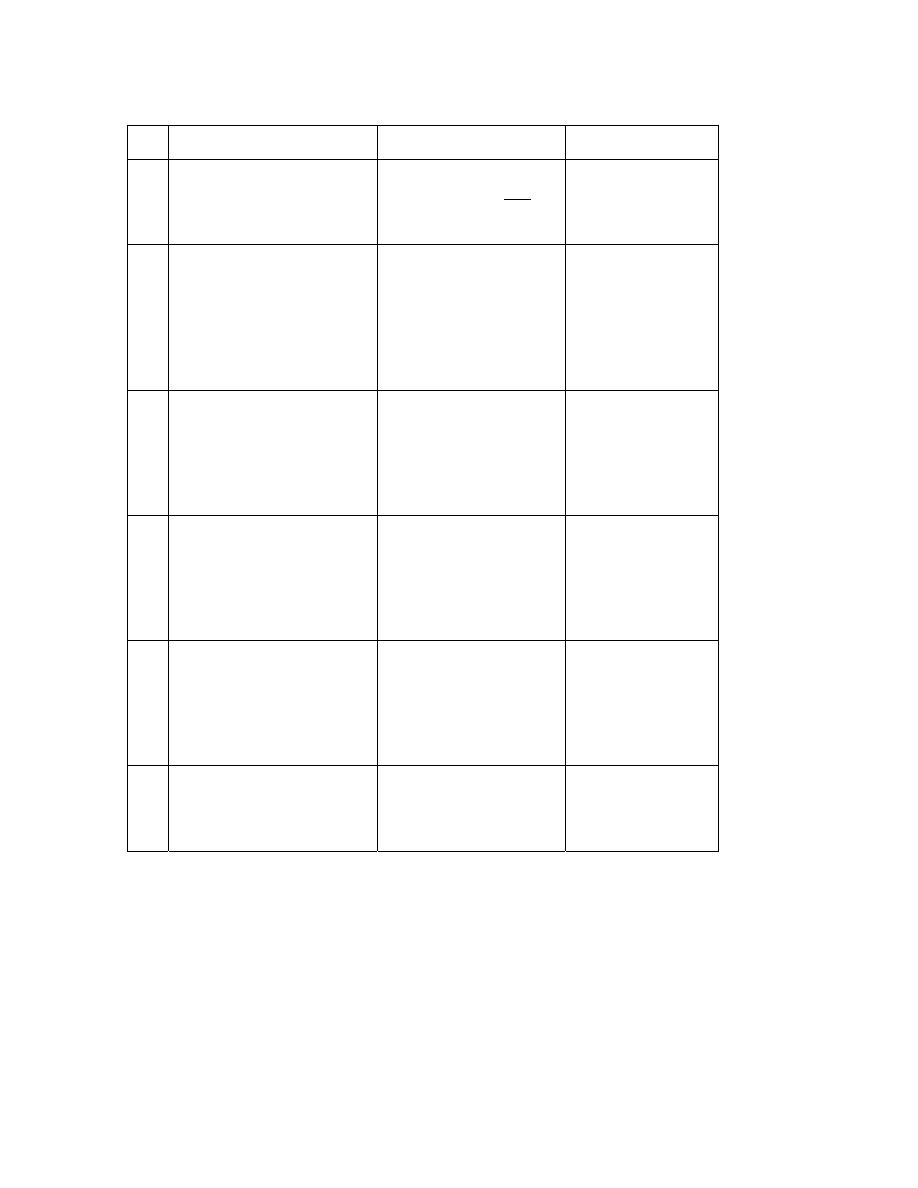

PROTOCOL 5

PROTOCOL 6

PROTOCOL 7

Renal failure

(Acute/Chronic)

On haemo-or peritoneal

dialysis

Renal failure

(acute/chronic ) Not on

haemo or peritoneal

dialysis

Hepatic failure (C)

Encephalopathy

Day 1

Urine output> 1000ml/day

= 2L osmolite (80ml/hr)

Protein = 74g Energy =

2124Kcal

Urine output < 1000ml

Suplena 1175 ml (40

ml/hr = max rate)

Suplena (1175ml/dy)

40ml/hr (max rate)

Protein = 35,3g

Energy = 2350Kcal

Osmolite (500 ml)

20ml/hr

Protein = 18,5g

Energy = 531Kcal

Day 2

As Above

As Above

Osmolite (1000

ml)

40ml/hr

Protein = 37g

Energy =

1062Kcal

Day 3

As Above

As Above

Osmolite (1500

ml)

60ml/hr

Protein = 55,5g

Energy =

1593Kcal

Day 4

As Above

As Above

Osmolite (2000

ml)

80ml/hr

Protein = 74g

Energy =

2124Kcal

Long-

ter

m

As Above

As Above

NB 1. Periative and Stresson Multifibre are contraindicated for hypotensive and severe

head patients (both products are rich in arginine which forms nitric oxide which is a

vasodilator, however arginine is very good for wound healing.

Ideally 80 ml/hr should be achieved in 3 days, but otherwise by day 5. if a patient does

not tolerate > 40ml/hr, consider supplementing the nutritional intake with peripheral

TPN.

Peptic (semi-elemental feed) is very high in carbohydrate (carb = 352g) – need to monitor

Dm and glucose intolerant pts. (2L Pepti = protein = 80g; Energy = 2000 Kcal)

26

COMMERCIALLY AVAILABLE PRODUCTS

Formulae

(1000 ml)

Kcal CHO

(g)

FAT

(g)

PROT

(g)

Kcal

: gN

OSM

mosmol/kg

R

cost

Use

Ensure 1100

162 37,2 39,7 150:1 480

10,7

5

Osmolite

1060

145 37,6 37,2 178:1

300

22,3

5

Nutrison 1000

122,5 38,9 40

131:1

290

17,6

8

Alitraq 1000

165 15,5 52,5 120:1 575

18,5

5

Impaired GI

function rich in

glutamine

(27g/100g)

Jevity 1060

151,7

35,9 44,4 150:1

300

24,6

5

Paediasure 1000 109,7

49,7

30

208:1

310

24,3

0

Peptison

1000

187,5

10 40 131:1

470

44,4

5

Glucerna

1000

33,3 50 16,7 150:1

375

7,98

Suplena 2000

255,2 95,6 30

418:1

600

7,98

Advera 1280

215,8 22,8 60 133:1

680

9,35

Examples of immunofeeds

IMPACT

IMMUNO-AID

Calories (kcal)

1000

1000

Protein (g)

56

37

Arginine (g)

12.5

14

Glutamine

9.0

Branch-chain amino acids (g)

20

Nucleic acids (g)

1.23

1.0

Fat (g)

27.8

22.0

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids

(%)

10.5 4.5

Osmolality (mosm/kg)

300

460

Vitamin C (mg)

67

60

Iron (mg)

12

9

Zinc (mg)

15

26

Selenium (

µg)

46 100

Copper (mg)

1.7

2

27