1

Fifth stage

Ophthalmology

Lec-2

.د

نزار

30/11/2016

The lens and cataract

Introduction

The lens is biconvex and transparent. It is held in position behind the iris by the suspensory

ligament whose zonular fibers are composed of the protein fibrillin which attach its equator

to the ciliary body. Disease may affect structure, shape and position.

Cataract

Opacification of the lens of the eye (cataract) is the commonest cause of treatable blindness

in the world. The large majority of cataracts occur in older age as a result of the cumulative

exposure to environmental and other influences such as smoking, UV radiation and elevated

blood sugar levels. This is sometimes referred to as age-related cataract. A smaller number

are associated with specific ocular or systemic disease and defined physico-chemical

mechanisms. Some are congenital and may be inherited.

Ocular conditions associated with cataract

1. Trauma Uveitis

2. High myopia

3. Topical medication (particularly steroid eye drops) Intraocular tumor

Systemic causes

1. Diabetes

2. Other metabolic disorders (galactosaemia, Fabry’s disease, hypocalcaemia)

3. Systemic drugs (particularly steroids, chlorpromazine) Infection (congenital

rubella)

4. Myotonic dystrophy Atopic dermatitis

5. Systemic syndromes (Down’s, Lowe’s) Congenital, including inherited, cataract

X-radiation

SYMPTOMS

An opacity in the lens of the eye:

Causes a painless loss of vision;

Causes glare;

May change refractive error.

In infants, cataract may cause amblyopia (a failure of normal visual development) because

the retina is deprived of a formed image. Infants with suspected cataract or a family history

of congenital cataracts should be seen as a matter of urgency by an ophthalmologist.

2

SIGNS

Visual acuity is reduced. In some patients the acuity measured in a dark room may seem

satisfactory, whereas if the same test is carried out in bright light or sunlight the acuity will

be seen to fall, as a result of glare and loss of contrast.

The cataract appears black against the red reflex when the eye is examined with a direct

ophthalmoscope (see pp. 29–30). Slit lamp examination allows the cataract to be examined

in detail and the exact site of the opacity can be identified. (Fig. 8.2).

INVESTIGATION

This is seldom required unless a suspected systemic disease requires exclusion or the cataract

appears to have occurred at an early age.

TREATMENT

Management remains surgical. ’The test is whether or not the cataract produces sufficient

visual symptoms to reduce the quality of life. Patients may have difficulty in recognizing faces,

reading or achieving the driving standard. Some patients may be greatly troubled by glare.

Patients are informed of their visual prognosis and must also be informed of any coexisting

eye disease which may influence the outcome of cataract surgery.

Cataract surgery

The operation involves removal of most of the lens and its replacement optically by a plastic

implant under local rather than general anaesthesia.

The operation can be performed:

• Through an extended incision at the periphery of the cornea or anterior sclera followed

by extra-capsular cataract extraction (ECCE). The incision must be sutured.

• By liquification of the lens using an ultrasound probe introduced through a smaller

incision in the cornea or anterior sclera (phacoemulsification). Usually no suture is

required. This is now the preferred method in the Western world.

The power of the intraocular lens implant to be used in the operation is calculated

beforehand by measuring the length of the eye ultrasonically and the curvature of the cornea

(and thus optical power) optically (this is called Biometry)

Visual rehabilitation and the prescription of new glasses is much quicker with

phacoemulsification. Since the patient cannot accommodate he or she will need glasses for

close work even if they are not needed for distance. Multifocal intraocular lenses are now in

use. Accommodating intraocular lenses are being developed.

3

Complications of cataract surgery

1. Vitreous loss.

2. Iris prolapse.

3. Endophthalmitis. A serious but rare infective complication of cataract extraction (less

than 0.3%). Patients present with:

A painful red eye;

Reduced visual acuity, usually within a few days of surgery;

A collection of white cells in the anterior chamber (hypopyon). The patient

requires urgent ophthalmic assessment, sampling of aqueous and vitreous for

microbiological analysis and treatment with intravitreal, topical and systemic

antibiotics.

4. Postoperative astigmatism.

5. Cystoid macular oedema.

6. Retinal detachment.

7. Opacification of the posterior capsule.

8. If the fine nylon sutures are not removed after surgery they may break in the following

months or years causing irritation or infection. Symptoms are cured by removal.

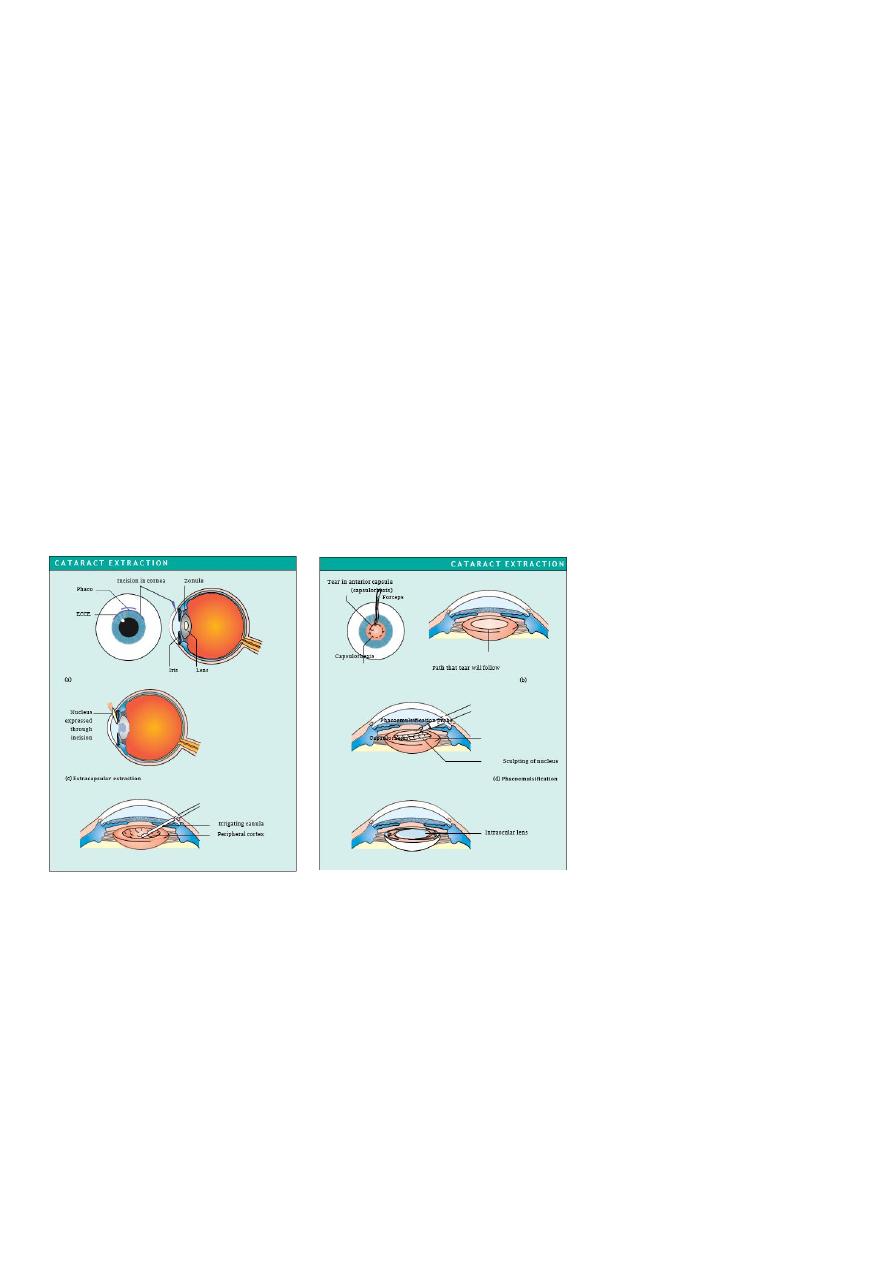

Fig. 8.3 Stages in the removal of a

cataract and the placement of an

intraocular lens. (a) An incision is

made in the cornea or anterior

sclera. A small, stepped self-sealing

incision

is

made

for

phacoemulsification.

(b)

The

anterior capsule of the lens is

removed. A variety of different

methods are used to do this. In ECCE

a ring of small incisions is made

with a needle to perforate the

capsule allowing the centre portion to be removed. In phacoemulsification the capsule is torn in a circle

leaving a strong smooth edge to the remaining anterior capsule. A canula is then placed under the anterior

capsule and fluid injected to separate the lens nucleus from the cortex allowing the nucleus to be rotated

within the capsular bag. (c) In ECCE the hard nucleus of the lens is removed through the incision, by

expression. Pressure on the eye causes the nucleus to pass out through the incision. (d) Alternatively the

nucleus can be emulsified in situ. The phacoemulsification probe, introduced through the small corneal or

scleral incision shaves away the nucleus. (e) The remaining soft lens matter is aspirated leaving only the

posterior capsule and the peripheral part of the anterior capsule. (f ) An intraocular lens is implanted into the

remains of the capsule. To allow implantation through the small phacoemulsification wound, the lens must

be folded in half or injected through a special introducer into the eye. The incision is repaired with fine nylon

sutures. If phacoemulsification has been used the incision in the eye is smaller and a suture is usually not

required.

4

Congenital cataract

The presence of congenital or infantile cataract is a threat to sight, not only because of the

immediate obstruction to vision but because disturbance of the retinal image impairs visual

maturation in the infant and leads to amblyopia (see pp. 170–171). If bilateral cataract is

present and has a significant effect on visual acuity this will cause amblyopia and an

oscillation of the eyes (nystagmus). Both cataractous lenses require urgent surgery and the

fitting of contact lenses to correct the aphakia. The management of contact lenses requires

considerable input and motivation from the parents of the child.

The treatment of uniocular congenital cataract remains controversial. Unfortunately the

results of surgery are disappointing and vision may improve little because amblyopia

develops despite adequate optical correction with a contact lens. Treatment to maximize the

chances of success must be performed within the first few weeks of life and be accompanied

by a coordinated patching routine to the fellow eye to stimulate visual maturation in the

amblyopic eye. Increasingly intraocular lenses are being implanted in children over 2 years

old. The eye becomes increasingly myopic as the child grows, however, making choice of the

power of the lens difficult.

CHANGE IN LENS SHAPE

Abnormal lens shape is very unusual. The curvature of the anterior part of the lens may be

increased centrally (anterior lenticonus) in Alport’s syndrome, a recessively inherited

condition of deafness and nephropathy. An abnormally small lens may be associated with

short stature and other skeletal abnormalities.

CHANGE IN LENS POSITION (ECTOPIA LENTIS)

Weakness of the zonule causes lens displacement. The lens takes up a more rounded form

and the eye becomes more myopic. This may be seen in:

Trauma.

Inborn errors of metabolism (e.g. homocystinuria, a recessive disorder with mental

defect and skeletal features. The lens is usually displaced downwards).

Certain syndromes (e.g. Marfan’s syndrome, a dominant disorder with skeletal and

cardiac abnormalities and a risk of dissecting aortic aneurysm. The lens is usually

displaced upwards). There is a defect in the zonular protein due to a mutation in the

fibrillin gene.

The irregular myopia can be corrected optically although sometimes an aphakic correction

may be required if the lens is substantially displaced from the visual axis. Surgical removal

may be indicated, particularly if the displaced lens has caused a secondary glaucoma but

surgery may result in further complications.

5

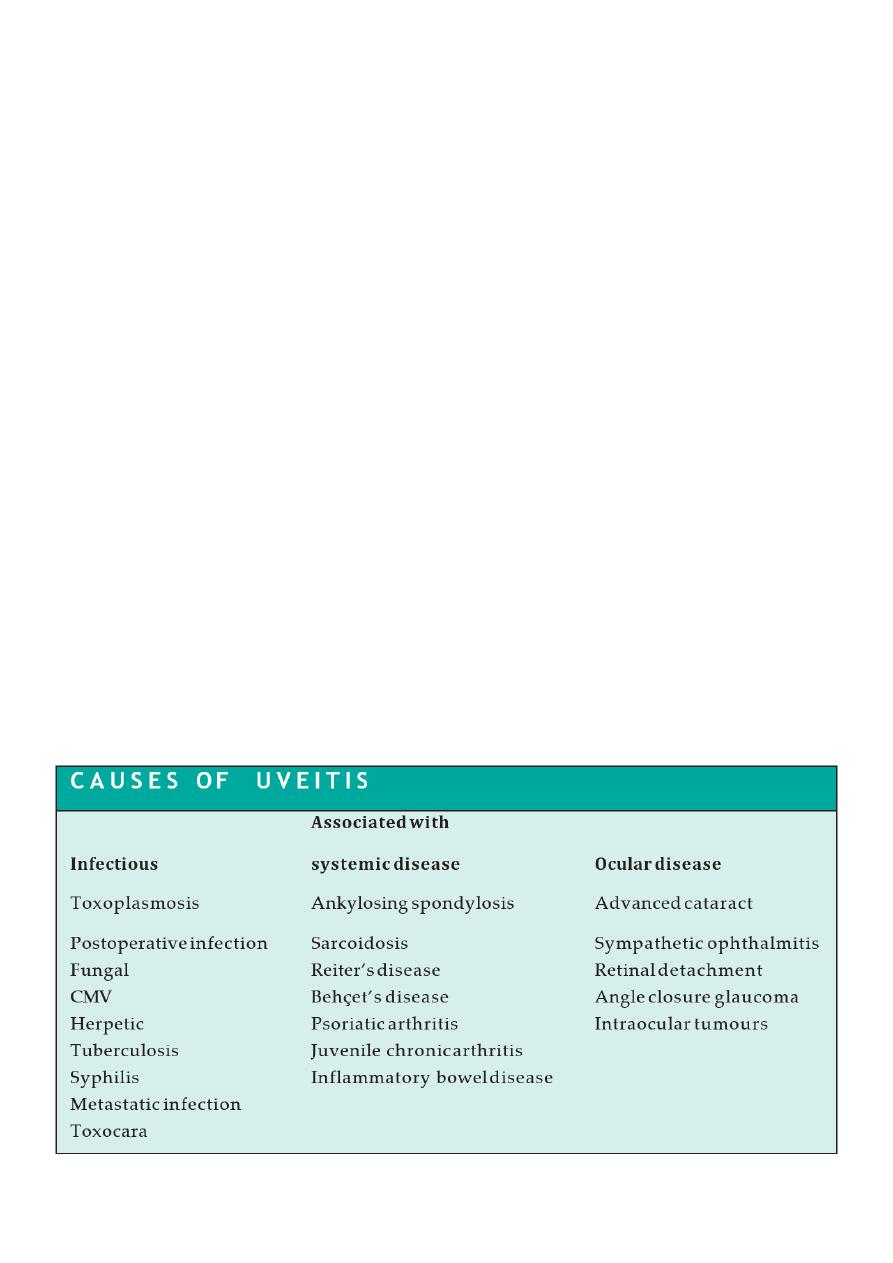

Uveitis

INTRODUCTION

Inflammation of the uveal tract (the iris, ciliary body and choroid) has many causes and is

termed uveitis (Fig. 9.1). It is usual for structures adjacent to the inflamed uveal tissue to

become involved in the inflammatory process. It may be classified anatomically:

• Inflammation of the iris, accompanied by increased vascular permeability, is termed

iritis or anterior uveitis (Fig. 9.2). White cells circulating in the aqueous humour of

the anterior chamber can be seen with a slit lamp. Protein which also leaks from the

blood vessels is picked out by its light scattering properties in the beam of the slit lamp

as a ‘flare’.

• An inflammation of the pars plana (posterior ciliary body) is termed

Cyclitis or intermediate uveitis.

• Inflammation of the posterior segment (posterior uveitis) results in inflammatory cells

in the vitreous gel. There may also be an associated choroidal or retinal inflammation

(choroiditis and retinitis respectively). A panuveitis is present when anterior and

posterior uveitis occur together.

HISTORY

The patient may complain of:

Ocular pain (less frequent with posterior uveitis or choroiditis);

Photophobia;

Blurring of vision;

Redness of the eye.

Posterior uveitis may not be painful.

The patient must be questioned about other relevant symptoms that may help determine

whether or not there is an associated systemic disease.

• Respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath, cough, and the nature of any

sputum produced (associated sarcoidosis or tuberculosis).

• Skin problems. Erythema nodosum (painful raised red lesions on the arms and legs)

may be present in granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis and Behçet’s disease.

Patients with Behçet’s may also have thrombophlebitis, dermatographia and oral and

genital ulceration. Psoriasis (in association with arthritis) may be accompanied by

uveitis.

6

• Joint disease. Ankylosing spondylitis with backpain is associated with acute anterior

uveitis. In children juvenile chronic arthritis may be associated with uveitis. Reiter’s

disease (classically urethritis, conjunctivitis and a seronegative arthritis) may also be

associated with anterior uveitis.

• Bowel disease. Occasionally uveitis may be associated with inflammatory bowel

diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease and Whipple’s disease.

Infectious disease. Syphilis with its protean manifestations can cause uveitis (particularly

posterior choroiditis). Herpetic disease (shingles) may also cause uveitis. Cytomegalovirus

(CMV) may cause a uveitis particularly in patients with AIDS. Fungal infections and

metastatic infections may also cause uveitis, usually in immunocompromised patients

SIGNS

On examination:

The visual acuity may be reduced.

The eye will be inflamed in acute anterior disease, mostly around the limbus (ciliary

injection).

Inflammatory cells may be visible clumped together on the endothelium of the cornea

particularly inferiorly (keratitic precipitates or KPs).

Slit lamp examination will reveal aqueous cells and flare. If the inflammation is severe

there may be sufficient white cells to collect as a mass inferiorly (hypopyon).

The vessels on the iris may be dilated.

The iris may adhere to the lens (posterior synechiae or PS).

The intraocular pressure may be elevated.

There may be cells in the vitreous.

There may be retinal or choroidal foci of inflammation.

Macular oedema may be present (see p. 121).

INVESTIGATIONS

These are aimed at determining a systemic association and are directed in part by the type

of uveitis present. An anterior uveitis is more likely to be associated with ankylosing

spondylitis and HLA-typing may help confirm the diagnosis. The presence of large KPs and

possibly nodules on the iris may suggest sarcoidosis; a chest radiograph, serum calcium and

serum angiotensin converting enzyme level would be appropriate. In toxoplasmic

retinochoroiditis the focus of inflammation often occurs at the margin of an old inflammatory

choroidal scar. A posterior uveitis may have an infectious or systemic inflammatory cause.

Some diseases such as CMV virus infections in HIV positive patients have a characteristic

appearance and with an appropriate history may require no further diagnostic tests.

Associated symptoms may also help point towards a systemic disease (e.g. fever, diarrhoea,

weight loss). Not all cases of anterior uveitis require investigation at first presentation unless

associated systemic symptoms are present.

7

TREATMENT

This is aimed at:

Relieving pain and inflammation in the eye;

Preventing damage to ocular structures; particularly to the macula and the optic nerve,

which may lead to permanent visual loss.

Steroid therapy is the mainstay of treatment. In anterior uveitis this is delivered by eye drops.

However, topical steroids do not effectively penetrate to the posterior segment. Posterior

uveitis is therefore treated with systemic steroids or steroids injected onto the orbital floor

or into the subtenon space.

In anterior uveitis, dilating the pupil relieves the pain from ciliary spasm and prevents the

formation of posterior synechiae by separating it from the anterior lens capsule. Synechiae

otherwise interfere with normal dilatation of the pupil. Dilation is achieved with mydriatics,

e.g. cyclopentolate or atropine drops. Atropine has a prolonged action. An attempt to break

any synechiae that have formed should be made with initial intensive cyclopentolate and

phenylephrine drops. A subconjunctival injection of mydriatics may help to break resistant

synechiae.

In posterior uveitis/retinitis visual loss may occur either from destructive processes caused

by the retinitis itself (e.g. in toxoplasma or CMV) or from fluid accumulation in the layers of

the macula (macular oedema). Apart from systemic or injected steroids, specific antiviral or

antibiotic medication may also be required. Some rare but severe forms of uveitis e.g. that

associated with Behçet’s disease may require treatment with other systemic

immunosuppresive drugs such as azathoprine or cyclosporin. Long-term treatment may be

necessary.

8

Fuchs’ heterochromic uveitis

This is a rare chronic uveitis usually found in young adults. The cause is uncertain and there

are no systemic associations.

HISTORY

The patient does not usually present with a typical history of iritis. Blurred vision and floaters

may be the initial complaint.

SIGNS

A mild anterior uveitis is present but without signs of conjunctival inflam- mation and there

are no posterior synechiae. There are KPs distributed diffusely over the cornea. The iris is

heterochromic due to loss of some of the pigment epithelial cells. The vitreous may be

inflamed and condensations (the cause of the floaters) may be present. About 70% of

patients develop cataract. Glaucoma occurs to a lesser extent.

TREATMENT

Steroids are not effective in controlling the inflammation and are thus not prescribed. The

patients usually respond well to cataract surgery when it is required. The glaucoma is treated

conventionally.

Toxoplasmosis

HISTORY

The infection may be congenital or acquired. Most ocular toxoplasmosis was thought to be

congenital with the resulting retinochoroiditis being reactivated in adult life. However, there

is now evidence that it is often acquired during a glandular fever-like illness. The patient may

complain of hazy vision, floaters, and the eye may be red and painful.

SIGNS

The retina is the principal structure involved with secondary inflammation occurring in the

choroid. An active lesion is often located at the posterior pole, appearing as a creamy focus

of inflammatory cells at the margin of an old chorioretinal scar (such scars are usually

atrophic, with a pigmented edge). Inflammatory cells cause a vitreous haze and the anterior

chamber may also show evidence of inflammation.

INVESTIGATION

The clinical appearance is usually diagnostic but a positive toxoplasma antibody test is

suggestive. However, a high percentage of the population have positive IgG titres due to prior

infection.

9

TREATMENT

The reactivated lesions will subside but treatment is required if the macula or optic nerve is

threatened or if the inflammatory response is very severe. Systemic steroids are

administered with an antiprotozoal drugs such as clindamycin. Care must be taken with the

use of sulphadiazines or clindamycin as pseudomembranous colitis may result from

clindamycin treatment. Patients must be warned that if diarrhoea develops they should seek

medical help immediately.

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and CMV retinitis

Ocular disease is a common manifestation of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Patients develop a variety of ocular conditions:

Microvascular occlusion causing retinal haemorrhages and cotton wool spots

(infarcted areas of the nerve fibre layer of the retina);

Corneal endothelial deposits;

Neoplasms of the eye and orbit;

Neuro-ophthalmic disorders including oculomotor palsies;

opportunistic infections of which the most common is CMV retinitis, (previously it was

seen in more than one-third of AIDS patients but the population at risk has decreased

significantly since the advent of highly active antiviral therapy (HAART) in the

treatment of AIDS). It typically occurs in patients with a CD4+ cell count of less than

50/ml). Toxoplasmosis, herpes simplex and herpes zoster are amongst other

infections that may be seen.

HISTORY

The patient may complain of blurred vision or floaters. A diagnosis of HIV disease has usually

already been made, often other AIDS defining features have occurred.

SIGNS

CMV retinopathy comprises a whitish area of retina, associated with haemorrhage, which

has been likened in appearance to ‘cottage cheese’. The lesions may threaten the macula or

the optic disc. There is usually an associated sparse inflammation of the vitreous.

TREATMENT

Chronic therapy with ganciclovir and/or foscarnet given parenterally are the current

mainstay of therapy; these drugs may also be given into the vitreous cavity. Cidofivir is

available for intravenous administration. Ganciclovir and its prodrug valganciclovir are

available orally. Systems of depot delivery into the vitreous are being actively researched for

local ocular CMV retinitis and a ganciclovir implant is available.

PROGNOSIS

Prolonged treatment is required to prevent recurrence.

11

SYMPATHETIC OPHTHALMITIS

A penetrating or surgical injury to one eye involving the retina may rarely excite a peculiar

form of uveitis which involves not only the injured eye but also the fellow eye. This is termed

sympathetic ophthalmitis (or ophthalmia).The uveitis may be so severe that in the worst

cases sight may be lost from both eyes. Fortunately systemic steroids, and particularly

cyclosporin, have greatly improved the chances of conserving vision. Sympathetic

ophthalmitis usually develops within 3 months of the injury or last ocular operation but may

occur at any time. The cause appears to be an immune response against retinal antigens at

the time of injury. It can be prevented by enucleation (removal) of the traumatized eye

shortly (within a week or so) after the injury if the prospects for visual potential in that eye

are very poor and there is major disorganization. Excision must precede the onset of signs in

the fellow eye.

SYMPTOMS

The patient may complain of pain and decreased vision in the Seeing Eye.

SIGNS

The iris appears swollen and yellow-white spots may be seen on the retina. There is a

panuveitis.

TREATMENT

High-dose systemic and topical steroids and also oral cyclosporin are required to reduce the

inflammation and try to prevent long term visual loss. It is vital to warn patients with ocular

trauma or multiple eye operations to attend an eye casualty department if they experience

any problems with their normal eye.

.

11

Glaucoma

INTRODUCTION

The glaucomas comprise a group of diseases in which damage to the optic nerve (optic

neuropathy) is usually caused by the effects of raised ocular pressure acting at the optic

nerve head. Independent ischaemia of the optic nerve head may also be important. Axon

loss results in visual field defects and a loss of visual acuity if the central visual field is

involved.

BASIC PHYSIOLOGY

The intraocular pressure level depends on the balance between production and removal of

aqueous humour. Aqueous is produced by secretion and ultrafiltration from the ciliary

processes into the posterior chamber. It then passes through the pupil into the anterior

chamber to leave the eye predominantly via the trabecular meshwork, Schlemm’s canal and

the episcleral veins (the conventional pathway). A small proportion of the aqueous (4%)

drains across the ciliary body into the supra-choroidal space and into the venous circulation

across the sclera (uveoscleral pathway).

Two theories have been advanced for the mechanism by which an elevated intraocular

pressure damages nerve fibres:

Raised intraocular pressure causes mechanical damage to the optic nerve axons.

Raised intraocular pressure causes ischaemia of the nerve axons by reducing

bloodflow at the optic nerve head.

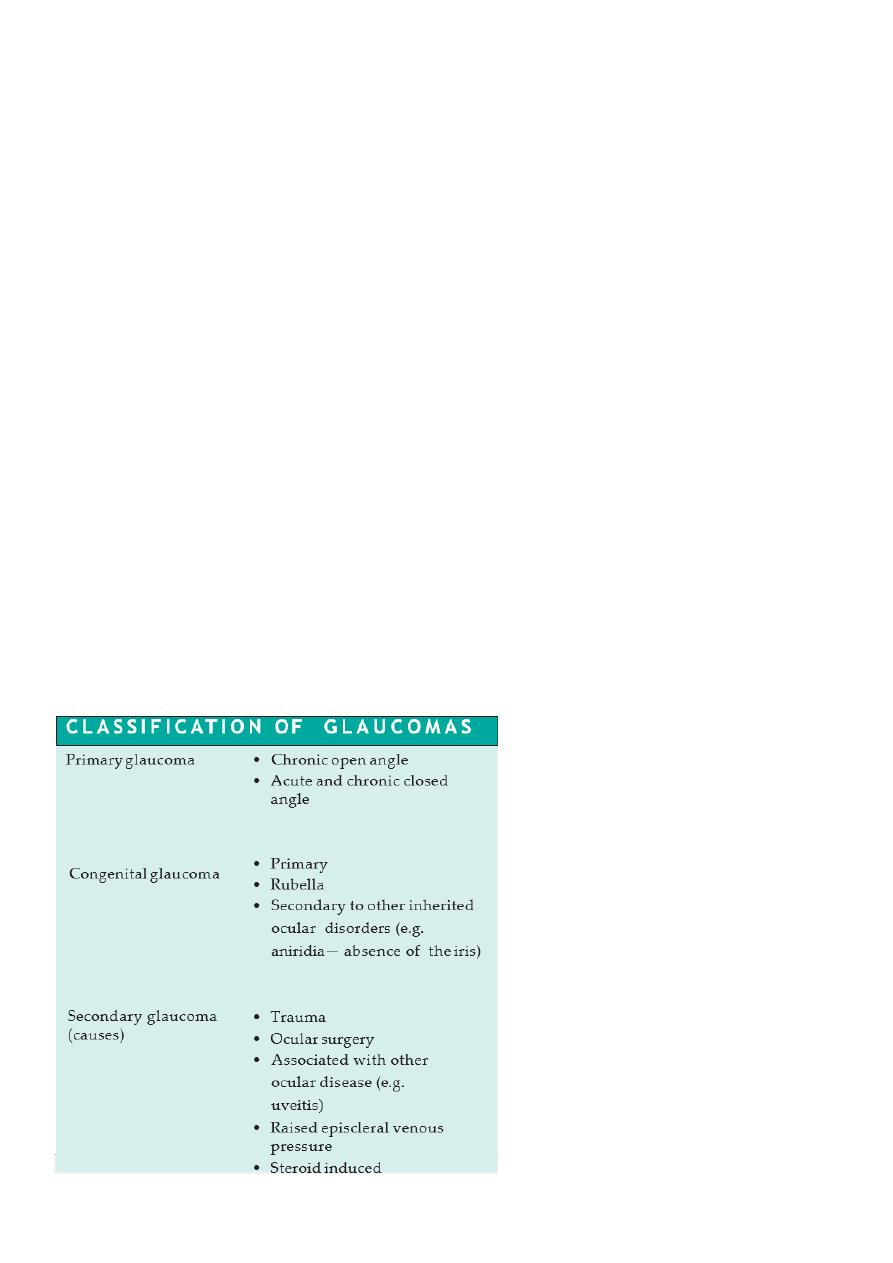

Classification

of

the

primary

glaucomas (Fig. 10.2) is based on

whether or not the iris is:

Clear of the trabecular meshwork

(open angle);

Covering the meshwork (closed angle).

12

PATHOGENESIS

Primary open angle glaucoma

A special contact lens (gonioscopy lens) applied to the cornea allows a view of the

iridocorneal angle with the slit lamp. In open angle glaucoma the structure of the trabecular

meshwork appears normal but offers an increased resistance to the outflow of aqueous

which results in an elevated ocular pressure. The causes of outflow obstruction include:

Thickening of the trabecular lamellae which reduces pore size;

Reduction in the number of lining trabecular cells;

Increased extracellular material in the trabecular meshwork.

A form of glaucoma also exists in which glaucomatous field loss and cupping of the optic disc

occurs although the intraocular pressure is not raised (normal or low tension glaucoma).

It is thought that the optic nerve head in these patients is unusually susceptible to the

intraocular pressure and/or has intrinsically reduced blood flow (Fig. 10.3).

Conversely, intraocular pressure may be raised without evidence of visual damage or

pathological optic disc cupping (ocular hypertension). These subjects may represent the

extreme end of the normal range of intraocular pressure; however, a small proportion will

subsequently develop glaucoma.

Closed angle glaucoma

The condition occurs in small eyes (i.e. often hypermetropic) with shallow anterior

chambers. In the normal eye the point of contact between the pupil margin and the lens

offers a resistance to aqueous entry into the anterior chamber (relative pupil block). In angle

closure glaucoma, sometimes in response to pupil dilation, this resistance is increased and

the pressure gradient created bows the iris forward and closes the drainage angle. These

peripheral iris adhesions are called peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS). Aqueous can no

longer drain through the trabecular meshwork and ocular pressure rises, usually abruptly.

Secondary glaucoma

Intraocular pressure usually rises in secondary glaucoma due to blockage of the trabecular

meshwork. i.e (open angle) the trabecular meshwork may be blocked by:

1. Blood (hyphaema), following blunt trauma.

2. Inflammatory cells (uveitis).

13

Pigment from the iris (pigment dispersion syndrome).

• Deposition of material produced by the epithelium of the lens, iris and ciliary body in

the trabecular meshwork (pseudoexfoliative glaucoma).

• Drugs increasing the resistance of the meshwork (steroid-induced glaucoma).

Secondary glaucoma may also result from blunt trauma to the eye damaging the angle

(angle recession).

Angle closure may also account for some cases of secondary glaucoma:

• Abnormal iris blood vessels may obstruct the angle and cause the iris to adhere to the

peripheral cornea, closing the angle (rubeosis iridis). This may accompany proliferative

diabetic retinopathy or central retinal vein occlusion due to the forward diffusion of

vasoproliferative factors from the ischaemic retina (Fig. 10.4 and Chapter 12).

• A large choroidal melanoma may push the iris forward approximating it to the

peripheral cornea causing an acute attack of angle closure glaucoma.

• A cataract may swell, pushing the iris forward and closing the drainage angle.

• Uveitis may cause the iris to adhere to the trabecular meshwork.

Raised episcleral venous pressure is an unusual cause of glaucoma but may be seen in

caroticocavernous sinus fistula where a connection between the carotid artery or its

meningeal branches and the cavernous sinus, causes a marked elevation in orbital venous

pressure. It is also thought to be the cause of the raised intraocular pressure in patients

with the Sturge–Weber syndrome.

The cause of congenital glaucoma remains uncertain. The iridocorneal angle may be

developmentally abnormal, and covered with a membrane.

Chronic open angle glaucoma

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Chronic open angle glaucoma affects 1 in 200 of the population over the age of 40, affecting

males and females equally. The prevalence increases with age to nearly 10% in the over 80

population. There may be a family history, although the exact mode of inheritance is not

clear.

GENETICS

First degree relatives of patients with chronic open angle glaucoma have up to a 16% chance

of developing the disease themselves

14

HISTORY

The symptoms of glaucoma depend on the rate at which intraocular pressure rises. Chronic

open angle glaucoma is associated with a slow rise in pressure and is symptomless unless the

patient becomes aware of a severe visual deficit. Many patients are diagnosed when the signs

of glaucoma are detected by their optometrist.

EXAMINATION

Assessment of a glaucoma suspect requires a full slit lamp examination:

• To measure ocular pressure with a tonometer. The normal pressure is 15.5 mmHg.

The limits are defined as 2 standard deviations above and below the mean (11–21

mmHg). In chronic open angle glaucoma the pressure is typically in the 22–40 mmHg

range. In angle closure glaucoma it rises above 60 mmHg.

• To examine the iridocorneal angle with the gonioscopy lens to confirm that an open

angle is present.

• To exclude other ocular disease that may give rise to a secondary cause for the

glaucoma.

• To examine the optic disc and determine whether it is pathologically cupped. Cupping

is a normal feature of the optic disc (Fig. 10.5(a)). The disc is assessed by estimating

the vertical ratio of the cup to the disc as a whole (the cup to disc ratio). In the normal

eye the cup disc ratio is usually no greater than 0.4. There is, however, a considerable

range (0– 0.8) and the size of the cup is related to the size of the disc. In chronic

glaucoma, axons entering the optic nerve head die. The central cup expands and the

rim of nerve fibres (neuroretinal rim) becomes thinner. The nerve head becomes

atrophic. The cup to disc ratio in the vertical is greater than 0.4 and the cup deepens.

If the cup is deep but the cup to disc ratio is lower than 0.4, then chronic glaucoma is

unlikely unless the disc is very small. Notching of the rim implying focal axon loss may

also be a sign of glaucomatous damage.

• Scanning the disc with a confocal ophthalmoscope to produce an image of the disc.

The neuroretinal rim area can be calculated from the image (Fig. 10.6). Other

techniques record the thickness of the nerve fiber layer around the optic disc.

• Field testing (perimetry, see pp. 21–23) is used to establish the presence of islands of

field loss (scotomata) and to follow patients to determine whether visual damage is

progressive (Fig. 10.7). A proportion of nerve fibres may, however, be damaged before

field loss becomes apparent

15

Fig. 10.7 The characteristic pattern of visual field

loss in chronic open angle glaucoma: (a) an upper

arcuate scotoma, reflecting damage to a cohort

of nerve fibres entering the lower pole of the disc

(remember— the optics of the eye determine that

damage to the lower retina creates an upper field

defect);

(b) The field loss has progressed, a small central

island is left (tunnel vision), and sometimes this

may be associated with a sparing of an island of

vision in the temporal field.

Symptoms and signs of chronic open angle glaucoma.

• Symptomless

• Raised intraocular pressure

• Visual field defect

• Cupped optic disc

TREATMENT

Treatment is aimed at reducing intraocular pressure. The level to which the pressure must

be lowered varies from patient to patient, and is that which minimizes further glaucomatous

visual loss. This requires careful monitoring in the outpatient clinic. Three modalities of

treatment are available:

1 Medical treatment;

2 Laser treatment;

3 Surgical treatment.

MEDICAL TREATMENT

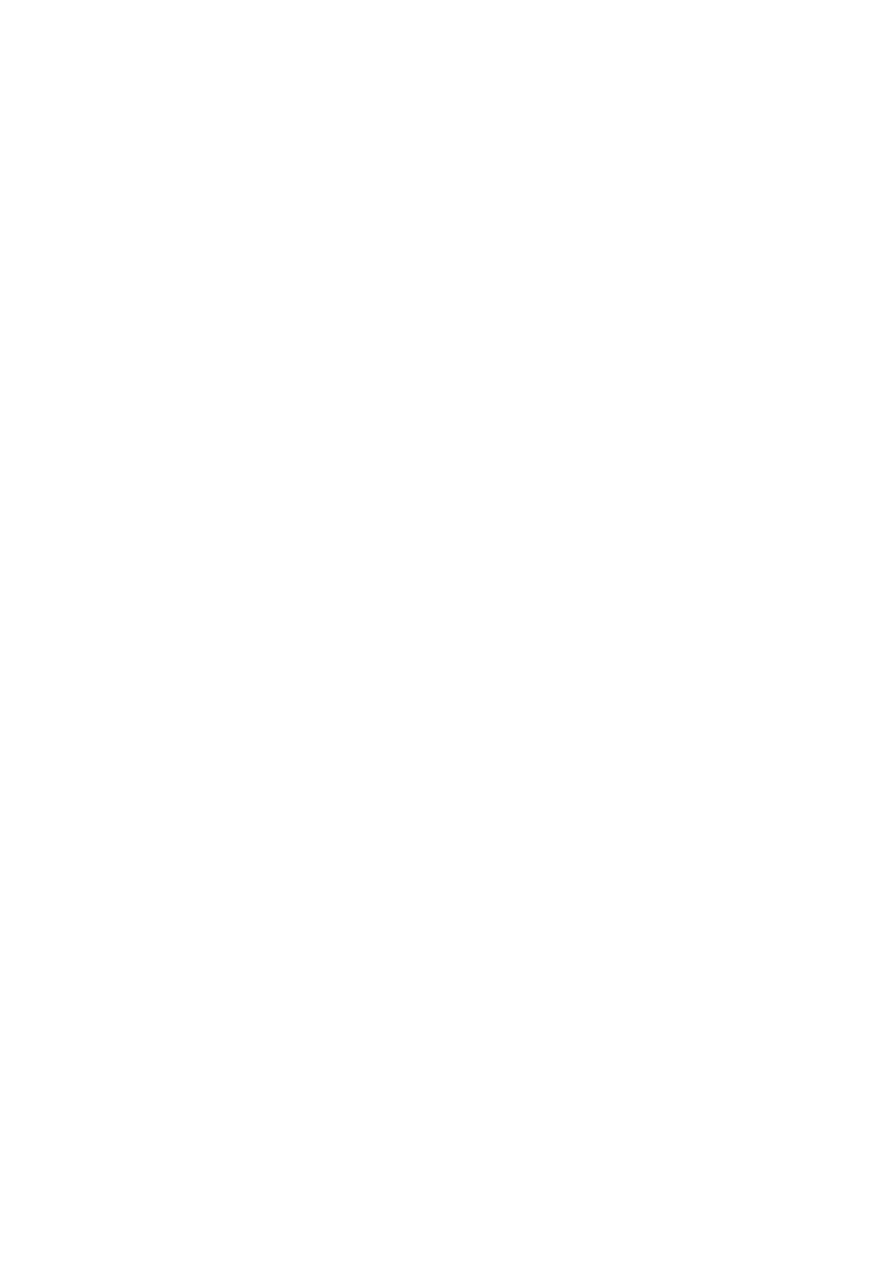

Topical drugs commonly used in the treatment of glaucoma are listed in Table 10.1. In chronic

open angle (although some of the newer drugs are challenging this, offering more

convenient dosing and fewer side effects, e.g. the prostaglandin analogue glaucoma topical

adrenergic beta- blockers are the usual first line treatment es). They act by reducing

aqueous production. Beta-selective beta-blockers, which may have fewer systemic side

effects, are available but must still be used with caution in those with respiratory disease,

particularly asthma, which may be exacerbated even by the small amount of beta-blocker

absorbed systemically. If intraocular pressure remains elevated the choice lies between:

• adding additional medical treatment;

• laser treatment;

• Surgical drainage procedures.

LASER TRABECULOPLASTY

16

SURGICAL TREATMENT

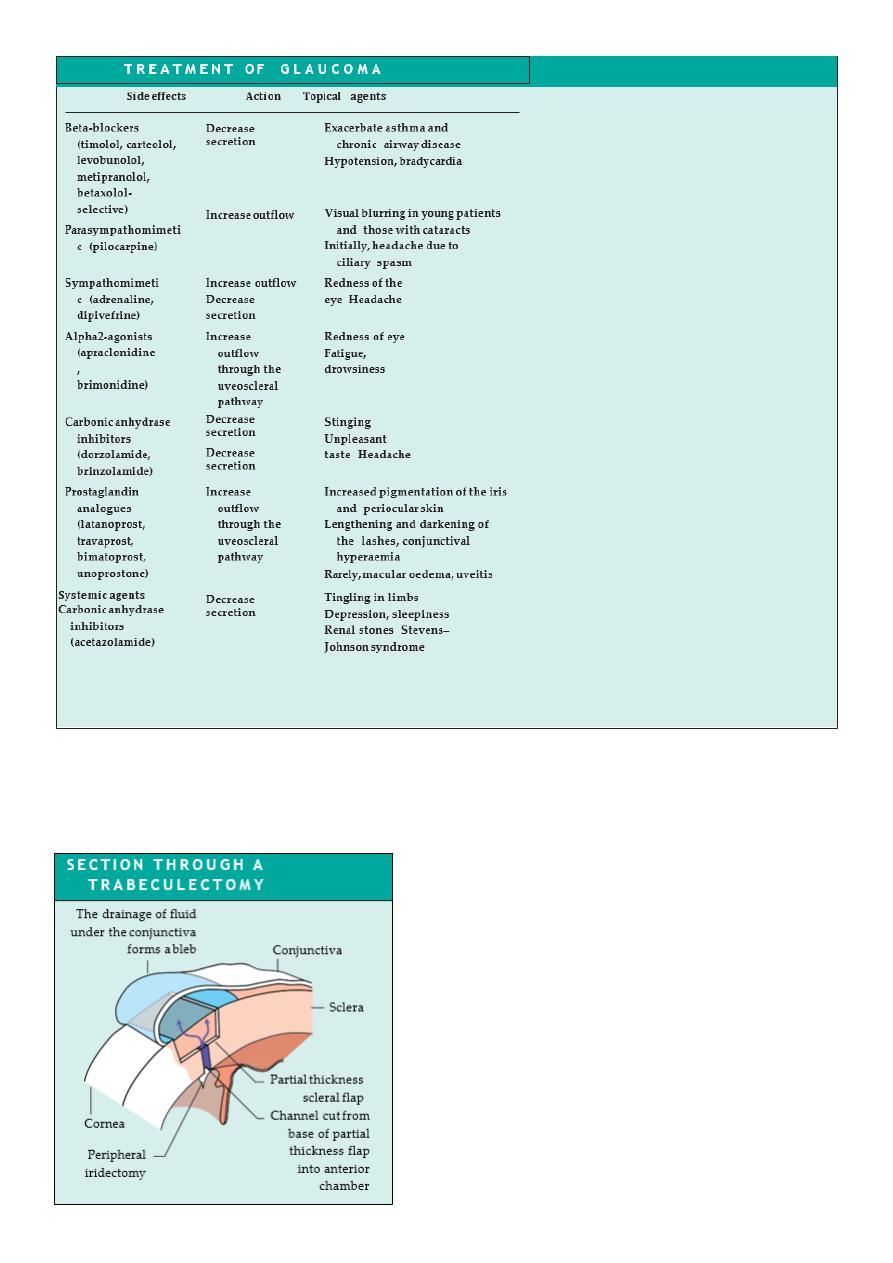

Drainage surgery (trabeculectomy) relies on the creation of a fistula between the anterior

chamber and the subconjunctival space (Fig. 10.8

Diagram showing a section through a trabeculectomy. An

incision is made in the conjunctiva, which is dissected and

reflected to expose bare sclera. A partial thickness scleral

flap is then fashioned. Just anterior to the scleral spur a

small opening (termed a sclerostomy) is made into the

anterior chamber to create a low resistance channel for

aqueous. The iris is excised in the region of the sclerostomy

(iridectomy) to prevent it moving forward and blocking the

opening. The partial thickness flap is loosely sutured back

into place. The conjunctiva is tightly sutured. Aqueous can

now leak through the sclerostomy, around and through the

scleral flap and underneath the conjunctiva where it forms

a bleb.

17

Complications of surgery include:

• Shallowing of the anterior chamber in the immediate postoperative period risking

damage to the lens and cornea;

• Intraocular infection;

• Possibly accelerated cataract development;

• Failure to reduce intraocular pressure adequately.

In patients particularly prone to scarring, antimetabolite drugs (5-flurouracil and mitomycin)

may be used at the time of surgery to prevent fibrosis.

Recent research has examined the benefit of modifying the trabeculectomy operation by

removing the sclera under the scleral flap but not making a fistula into the anterior chamber

(deep sclerostomy, visco- canalostomy). The long term benefit of the procedure is being

assessed.

NORMAL TENSION GLAUCOMA

Normal tension glaucoma, considered to lie at one end of the spectrum of chronic open angle

glaucoma, can be particularly difficult to treat. Some patients appear to have non-progressive

visual field defects and require no treatment. In those with progressive field loss lowering

intraocular pressure may be beneficial.

Primary angle closure glaucoma

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Primary angle closure glaucoma affects 1 in 1000 subjects over 40 years old, with females

more commonly affected than males. Patients with angle closure glaucoma are likely to be

long-sighted because the long-sighted eye is small and the anterior chamber structures more

crowded.

HISTORY

There is an abrupt increase in pressure and the eye becomes very painful and photophobic.

There is watering of the eye and loss of vision. The patient may be systemically unwell with

nausea and abdominal pain, symptoms which may take them to a general casualty

department.

Intermittent primary angle closure glaucoma occurs when an acute attack spontaneously

resolves. The patient may complain of pain, blurring of vision and seeing haloes around

lights.

18

EXAMINATION

On examination visual acuity is reduced, the eye red, the cornea cloudy and the pupil oval,

fixed and dilated.

TREATMENT

The acute and dramatic rise in pressure seen in angle closure glaucoma must be urgently

countered to prevent permanent damage to the vision. Acetazolamide is administered

intravenously and subsequently orally together with topical pilocarpine and beta-blockers.

Pilocarpine constricts the pupil and draws the peripheral iris out of the angle; the

acetazolamide and beta-blocker reduce aqueous secretion and the pressure across the iris.

These measures usually break the attack and lower intraocular pressure. Subsequent

management requires that a small hole (iridotomy or iridectomy) is made in the peripheral

iris to prevent subsequent attacks. This provides an alternative pathway to the pupil for fluid

to flow from the posterior to the anterior chamber reducing the pressure gradient across the

iris. This can be done with a YAG laser or surgically. If the pressure has been raised for some

days the iris becomes adherent to the peripheral cornea (peripheral anterior synechiae or

PAS). The iridocorneal angle is damaged and additional medical or surgical measures may be

required to lower the ocular pressure.

Secondary glaucoma

Secondary glaucomas are much rarer than the primary glaucomas. The symptoms and signs

depend on the rate at which intraocular pressure rises; most are again symptomless.

Treatment broadly follows the lines of the primary disease. In secondary glaucoma it is

important to treat any underlying cause, e.g. uveitis, which may be responsible for the

glaucoma.

In particularly difficult cases it may be necessary to selectively ablate the ciliary processes in

order to reduce aqueous production. This is done by application of a laser or cryoprobe to

the sclera overlying the processes

Congenital glaucoma

It may present at birth or within the first year. Symptoms and signs include:

• Excessive tearing;

• An increased corneal diameter (buphthalmos);

• A cloudy cornea due to epithelial oedema;

• Splits in Descemet’s membrane.

19

Congenital glaucoma is usually treated surgically. An incision is made into the trabecular

meshwork (goniotomy) to increase aqueous drainage or a direct passage between

Schlemm’s canal and the anterior chamber is created (trabeculotom

(

.

• Glaucoma is an optic neuropathy caused by an elevation of intraocular pressure.Y

POINTS

• Primary glaucoma is classified according to whether the trabecular meshwork is

obstructed by the peripheral iris (angle closure) or not (open angle glaucoma).

• Treatment of glaucoma relies on lowering ocular pressure to reduce or prevent

further visual damage.

• Ocular pressure can be reduced with topical and systemic medications, laser

treatment and surgery.

• Beware patients who are acutely debilitated with a red eye; they may have acute

angle closure glaucoma.

• If the diagnosis is made late arresting the glaucoma completely may still result in

visual loss during the patient’s lifetime. This emphasizes the need for early diagnosis