بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم

Tuberculosis

Lcture by : Dr. Zaidan Jayed

Epidemiology

Tuberculosis (TB) is caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis(MTB), which is part of a complex of organisms including M. bovis(reservoir cattle) and M. africanum(reservoir human). Recent figures suggest a decline in the incidence of TB, but its impact on world health remains significant. In 2010, an estimated 8.8 million incident cases occurred and TB was estimated to account for nearly 1.5 million deaths, makingit the second most common cause of death due to an infective disease. Furthermore, it is estimated that around one-third of the world’s population has latent TB. The majority of cases occur in the world’s poorest nations, who struggle to cover the costs associated with management and control programmes.

In Africa, the resurgence of TB has been largely driven by HIV disease and, in the former Soviet Union and Baltic states, by a lack of appropriate health care associated with social and political upheaval.

Pathology and pathogenesis

M. Bovis infection arises from drinking non-sterilisedmilk from infected cows. M. Tuberculosis is spread by the inhalation of aerosolised droplet nuclei from other

infected patients. Once inhaled, the organisms lodge in

the alveoli and initiate the recruitment of macrophages

and lymphocytes. Macrophages undergo transformation into epithelioid and Langhans cells, which aggregate with the lymphocytes to form the classical

tuberculous granuloma.

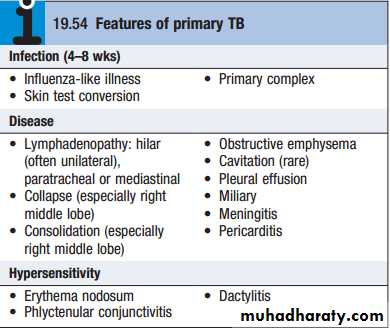

Numerous granulomas aggregate to form a primary lesion or ‘Ghon focus’ (a pale yellow, caseous nodule, usually a few millimetres to 1–2 cm in diameter), which is characteristically situated in the periphery of the lung. Spread of organisms to the hilar lymph nodes is followed by a similar pathological reaction, and the combination of the primary lesion and regional lymph nodes is referred to as the ‘primary complex of Ranke’. Reparative processes encase the primary complex in a fibrous capsule, limiting the spread of bacilli: so-called latent TB.

If no further complications ensue, this lesion calcifies and is clearly seen on a chest X-ray. However, lymphatic or haematogenous spread may occur before immunity is established, seeding secondary foci in other organs, including lymph nodes, serous membranes, meninges, bones, liver, kidneys and lungs, which may lie dormant for years. The only clue that infection has occurred may be the appearance of a cell-mediated, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to tuberculin, demonstrated by tuberculin skin testing. If these reparative processes fail, primary progressive disease ensues eventually.

The estimated lifetime risk of developing

disease after primary infection is 10%, with roughly half of this risk occurring in the first 2 years after infection.Clinical features: pulmonary disease

Miliary TB

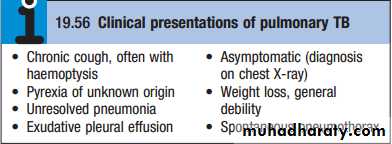

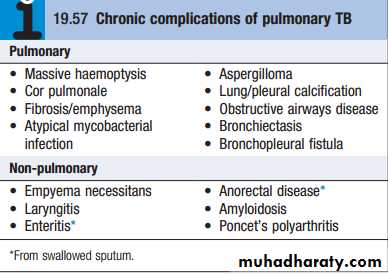

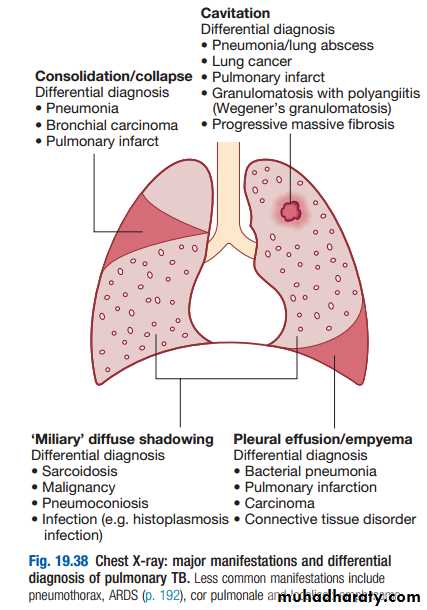

Blood-borne dissemination gives rise to miliary TB, which may present acutely but more frequently is characterised by 2–3 weeks of fever, night sweats, anorexia, weight loss and a dry cough. Hepatospleno megaly may develop and the presence of a headache may indicate coexistent tuberculous meningitis. Auscultation of the chest is frequently normal, but in more advanced disease, widespread crackles are evident. Fundoscopy may show choroidal tubercles. The classical appearances on chest X-ray are of fine 1–2 mm lesions (‘millet seed’) distributed throughout the lung fields, although occasionally the appearances are coarser. Anaemia and leucopenia reflect bone marrow involvement.‘Cryptic’ miliary TB is an unusual presentation sometimes seen in old age

Post-primary pulmonary TB

Post-primary disease refers to exogenous (‘new’ infection) or endogenous (reactivation of a dormant primary lesion) infection in a person who has been sensitised by earlier exposure. It is most frequently pulmonary and characteristically occurs in the apex of an upper lobe,where the oxygen tension favours survival of the strictly

aerobic organism. The onset is usually insidious, developing slowly over several weeks. Systemic symptoms include fever, night sweats, malaise, and loss of appetite and weight, and are accompanied by progressive pul-monary symptoms.

Very occasionally, this form of TB may present with one of the complications

Radiological changes include ill-defined opacification in one or both of the upper lobes, and as progression occurs, consolidation, collapse and cavitation develop to varying degrees

It is often difficult to distinguish active from quiescent disease on radiological criteria alone, but the presence of a miliary pattern or cavitation favours active disease. In extensive disease, collapse may be marked and results in significant displacement of the trachea and mediastinum. Occasionally, a caseous lymph node may drain into an adjoining bronchus, leading to tuberculous pneumonia.

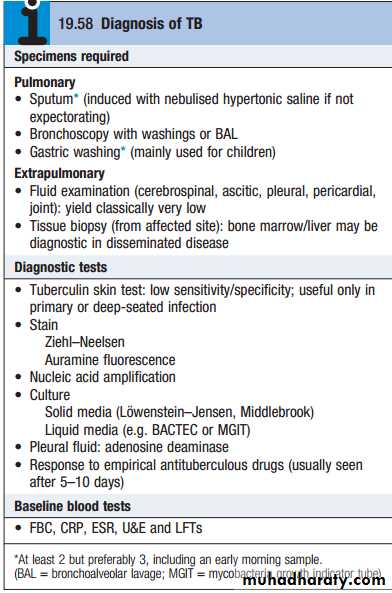

Diagnosis

The presence of an otherwise unexplained cough for more than 2–3 weeks, particularly in regions where TB is prevalent, or typical chest X-ray changes.Direct microscopy of sputum remains the most important first step. The probability of detecting acid-fast bacilli is proportional to the bacillary burden in the sputum (typically positive when 5000–10 000 organisms are present). By virtue of their substantial, lipid-rich wall, tuberculous bacilli are difficult to stain. The most effective techniques are the Ziehl–Neelsen and rhodamine–auramine.

The latter causes the tuberculous bacilli to fluoresce against a dark background and is easier to use when numerous specimens need to be examined; however, it is more complex and expensive, limiting use in resource-poor regions.A positive smear is sufficient for the presumptive

diagnosis of TB but definitive diagnosis requires culture. Smear-negative sputum should also be cultured, as only

10–100 viable organisms are required for sputum to be

culture-positive. A diagnosis of smear-negative TB may

be made in advance of culture if the chest X-ray appearances are typical of TB and there is no response

to a broad-spectrum antibiotic.

MTB grows slowly and may take between 4 and 6 weeks to appear on solid medium, such as Löwenstein–Jensen or Middlebrook. Faster growth (1–3 weeks) occurs in liquid media, such as the radioactive BACTEC system or the non-radiometric mycobacteria growth indicator tube (MGIT). The BACTEC method is the most widely accepted as the reference standard in developed nations and detects mycobacterial growth by measuring the liberation of 14CO2, following metabolism of 14C-labelled substrate present in the medium.

Drug sensitivity testing is particularly important in

those with a previous history of TB, treatment failureor chronic disease, and in those who are resident in or

have visited an area of high prevalence of resistance, or

who are HIV-positive. The detection of rifampicin resistance, using molecular tools to test for the presence of the rpogene currently associated with around 95% of rifampicin-resistant cases, is important, as rifampicin forms the cornerstone of 6-month chemotherapy.

Nucleic acid amplification tests, such as the Xpert/RIF test, combine the potential to diagnose TB and detect the presence of rifampicin resistance, and may become the test of first choice in individuals with HIV or those suspected to have multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). If a cluster of cases suggests a common source, confirmation may be sought by fingerprinting of isolates with restriction-fragment length polymorphism (RFLP).

The diagnosis of extrapulmonary TB can be more

challenging. There are generally fewer organisms (par-ticularly in meningeal or pleural fluid), so culture orhistopathological examination of tissue is more impor-tant. Adenosine deaminase in pleural fluid, and to a

lesser extent in CSF, may assist in confirming suspected

TB. In the presence of HIV, examination of sputum may

still be useful, as subclinical pulmonary disease is

common.

Management

Chemotherapy:The treatment of TB is based on the principle of an initial intensive phase to reduce the bacterial population rapidly, followed by a continuation phase to destroy any remaining bacteria.

Most patients can be treated at home. Admission to a hospital unit with appropriate isolation facilities should be considered where there is uncertainty about the diagnosis, intolerance of medication, questionable

treatment adherence, adverse social conditions or a sig-nificant risk of MDR-TB (culture-positive after 2 months on treatment, or contact with known MDR-TB).

Corticosteroids reduce inflammation and limit tissue

damage, and are currently recommended when treatingpericardial or meningeal disease, and in children with

endobronchial disease. They may confer benefit in TB of

the ureter, pleural effusions and extensive pulmonary

disease, and can suppress hypersensitivity drug reac-tions. Surgery should be considered in cases compli-cated by massive haemoptysis, loculated empyema,

constrictive pericarditis, lymph node suppuration, and

spinal disease with cord compression, but usually only

after a full course of antituberculosis treatment.

The effectiveness of therapy for pulmonary TB is

assessed by further sputum smear at 2 months and at5 months. Treatment failure is defined as a positive

sputum smear or culture at 5 months or any patient

with a multidrug resistant strain, regardless of whether they are smear-positive or negative. Extrapulmonary TB must be assessed clinically or radiographically, as appropriate.

Control and prevention

The World Health Organization (WHO) is committed to reducing the incidence of TB by 2015. Supporting the development of laboratory and health-care services to improve detection and treatment of active and latent TB is an important component of this goal.Detection of latent TB

Contact tracing is a legal requirement in many countries.

It has the potential to identify the probable index case,

other cases infected by the same index patient (with or

without evidence of disease), and close contacts who

should receive BCG vaccination (see below) or chemo-therapy. Approximately 10–20% of close contacts of

patients with smear-positive pulmonary TB and 2–5% of

those with smear-negative, culture-positive disease have

evidence of TB infection.

An otherwise asymptomatic contact with a positive tuberculin skin test but a normal chest X-ray may be treated with chemoprophylaxis to prevent infection from progressing to clinical disease. Chemoprophylaxis is also recommended for children aged less than 16 years identified during contact tracing as having a strongly positive tuberculin test, children aged less than 2 years in close contact with smear-positive pulmonary disease, those in whom recent tuberculin conversion has been confirmed, and babies of mothers with pulmonary TB. It should also be considered for HIV-infected close contacts of a patient with smear-positive disease. A course of rifampicin and iso-niazid for 3 months or isoniazid for 6 months is effective.

Directly observed therapy

Poor adherence to therapy is a major factor in prolongedillness, risk of relapse, and the emergence of drug resistance. Directly observed therapy (DOT) involves the

supervised administration of therapy 3 times weekly to

improve adherence. DOT has become an important

control strategy in resource-poor nations. In the UK, it

is currently recommended for patients thought unlikely

to be adherent to therapy: homeless people and drifters,

alcohol or drug users, patients with serious mental

illness and those with a history of non-compliance.

TB and HIV/AIDS

The close links between HIV and TB, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, and the potential for both diseases to overwhelm health-care funding in resource-poor nations have been recognised, with the promotion of programmes that link detection and treatment of TB with detection and treatment of HIV. It is recommended that all patients with TB should be tested for HIV disease. Mortality is high and TB is a leading cause of death in HIV patients.

Drug-resistant TB

Drug-resistant TB is defined by the presence of resistance to any first-line agent. Multidrug-resistant TB(MDR-TB) is defined by resistance to at least rifampicin

and isoniazid, with or without other drug resistance.

Extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) is defined as

resistance to at least rifampicin and isoniazid, in addition to any quinolone and at least one injectable second-line agent. The prevalence of MDR-TB is rising, particularly in the former Soviet Union, Central Asia and Africa. It is more common in those with a prior history of TB, particularly if treatment has been inadequate, and those with HIV infection.

Vaccines

BCG (the Calmette–Guérin bacillus), a live attenuated vaccine derived from M. bovis, is the most established TB vaccine. It is administered by intradermal injection and is highly immunogenic. BCG appears to be effective in preventing disseminated disease, including tuberculous meningitis, in children, but its efficacy in adults is inconsistent and new vaccines are urgently needed.Current vaccination policies vary worldwide according to incidence and health-care resources, but usually target children and other high-risk individuals. BCG is very safe, with the occasional complication of local abscess formation. It should not be administered to those who are immunocompromised (e.g. by HIV) or pregnant.

Prognosis

Following successful completion of chemotherapy, cure should be anticipated in the majority of patients. There is a small (<5%) and unavoidable risk of relapse. Most relapses occur within 5 months and usually have the same drug susceptibility. In the absence of treatment, a patient with smear-positive TB will remain infectious for an average of 2 years; in 1 year, 25% of untreated cases will die. Death is more likely in those who are smear-positive and those who smoke. A few patients die unexpectedly soon after commencing therapy and it is possible that some have subclinical hypoadrenalism that is unmasked by a rifampicin-induced increase in steroid metabolism. HIV-positive patients have higher mortality rates and a modestly increased risk of relapse.THANK YOU FOR LISTENING