HEADACHE SYNDROMES

Dr. Omar A. MahmoodOBJECTIVES

To understand classification of headache syndromesTo discuss pathophysiology , clinical features of tension, migraine and cluster and other primary headache syndromes

To recognize symptoms and signs of ominous headache disorders.

To summarize diagnostic tests used for exclusion of secondary pathology

To review treatment principles of headache

Headache is common and causes considerable worry among both patients and clinicians, but rarely represents threatening disease. The causes may be divided into primary or secondary, with primary headache syndromes being much more common.

Primary headache syndromes

Migraine (with or without aura)Tension-type headache

Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia (including cluster headache, paroxysmal hemicrania, etc)

Primary stabbing/coughing/exersize/sex-related headache

Thunderclap headache syndromes

New daily persistent headache syndrome

Secondary causes of headache

• Medication overuse headache (chronic daily headache)

• Intracranial bleeding (subdural haematoma, subarachnoid or intracerebral haemorrhage)

• Raised intracranial pressure (brain tumour, idiopathic intracranial hypertension)

• Infection (meningitis, encephalitis, brain abscess)

• Inflammatory disease (temporal arteritis, other vasculitis)

• Referred pain from other structures (sinus headache, orbit, temporomandibular joint, neck)

Presentation

The primary purpose of the history and clinical examination in patients presenting with headache is to identify the small minority of patients with serious underlying pathology. Key features of the history include the temporal evolution of a headache; a headache that reached maximal intensity within 1 minutes of onset requires rapid assessment for possible subarachnoid haemorrhage.‘Red flag’ symptoms in headache

Thunderclap (maximum intensity within 1 minute) may indicate:Subarachnoid haemorrhage

reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome

cervical artery dissection

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis

Spontaneous intracranial hypotension

Pituitary apoplexy

Meningitis

Focal neurological symptoms (other than for typically migrainous)

Intracranial mass lesion

Vascular

Neoplastic

Infection

Constitutional symptoms:

MeningitisEncephalitis

Neoplasm (lymphoma or metastases)

Inflammation (vasculitis)

Raised intracranial pressure (worse on

waking/lying down, associated vomiting) may indicate : Intracranial mass lesionNew onset aged >60 years may indicate Temporal arteritis

Change in pattern of headache.

TENSION-TYPE HEADACHE

This is the most common type of headache and is experienced to some degree by the majority of the population.Pathophysiology

Tension-type headache is incompletely understood, and some consider that it is simply a milder version of migraine; certainly, the original notion that it is due primarily to muscle tension (hence the unsatisfactory name) has long since been dismissed. Anxiety about the headache itself may lead to continuation of symptoms, and patients may become convinced of a serious underlying condition.

Clinical features

The pain of tension headache is characterised as ‘dull’, ‘tight’ or like a ‘pressure’, and there may be a sensation of a bandround the head or pressure at the vertex. It is of constant character and generalised, but often radiates forwards from the occipital region. It may be episodic or persistent, although the severity may vary, and there is no associated vomiting or photophobia. Tension-type headache is rarely disabling and patients appear well. The pain often progresses throughout the day. Tenderness may be present over the skull vault or in the occiput but is easily distinguished from the triggered pains of trigeminal neuralgia and the exquisite tenderness of temporal arteritis. Analgesics may be taken with chronic regularity, despite little effect, and may perpetuate the symptoms.

Management

Most benefit is derived from a careful assessment, followed by discussion of likely precipitants and reassurance that the prognosis is good. The concept of medication overuse headache needs careful explanation. An important therapeutic step is to allow patients to realise that their problem has been taken seriously and thoroughly assessed. Physiotherapy (with muscle relaxation and stress management) may help and low-dose amitriptyline can provide benefit. Investigation is rarely required. The reassurance value of brain imaging needs careful assessment: the pick-up rate of structural abnormalities is exceedingly low, and significantly outweighed by the likelihood of identifying an incidental and irrelevant finding (e.g. an arachnoid cyst, Chiari I malformation or vascular abnormality). The value of such ‘reassurance’ is usually over-estimated by doctors and patients alike.MIGRAINE

Migraine usually appears before middle age, or occasionally in later life; it affects about 20% of females and 6% of males at some point in life. Migraine is usually readily identifiable from the history, although unusual variants can cause doubt.The cause of migraine is unknown but there is increasing evidence that the aura is due to dysfunction of ion channels causing a spreading front of cortical depolarisation (excitation) followed by hyperpolarisation (depression of activity). This process spreads over the cortex at a rate of about 3 mm/min, corresponding to the aura’s symptomatic spread. The headache phase is associated with vasodilatation of extracranial vessels and may be relayed by hypothalamic activity. Activation of the trigeminovascular system is probably important. A genetic contribution is implied by the frequently positive family history. The female preponderance and the frequency of migraine attacks at certain points in the menstrual cycle also suggest hormonal influences. Oestrogen-containing oral contraception increases the very small risk of stroke in patients who suffer from migraine with aura. Doctors and patients often over-estimate the role of dietary precipitants such as cheese, chocolate or red wine.

Clinical features

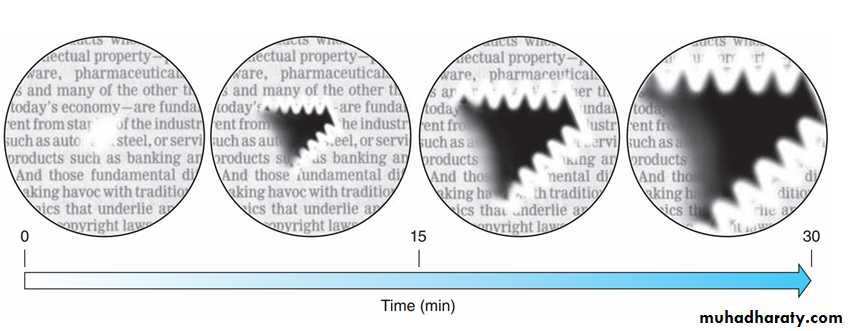

Some patients report a prodrome of malaise, irritability or behavioural change for some hours or days. Around 20% of patients experience an aura and are said to have migraine with aura (previously known as classical migraine). The aura may manifest as almost any neurological symptom but is most often visual, consisting of fortification spectra, which are usually positive phenomena such as glistening, silvery zigzag lines marching across the visual fields for up to 40 minutes, sometimes leaving a trail of temporary visual field loss (scotoma, see figure.1). Sensory symptoms characteristically spreading over 20–30 minutes, from one part of the body to another, are more common than motor ones, and language function can be affected, leading to similaritieswith TIA/stroke. Brain stem aura previously known as (basilar migraine) is another variant. Isolated aura without headache (migraine equivalent) may occur.

The 80% of patients with characteristic headache but no

‘aura’ are said to have migraine without aura (previously called ‘common’ migraine).Migraine headache is said to be when patient has at least five attacks of usually moderate to severe, throbbing, unilateral headache, worsen with movement with either photophobia/ phonophobia or nausea / vomiting lasting from 4 to 72 hours. and headache is not attributed to other causes.

In a small number of patients the aura may persist, leaving more permanent neurological disturbance. This persistent migrainous aura may occur with or without evidence of brain infarction.

Figure.1 evolution of scintillating scotoma in apatient with classic migraine

(Reprinted from Aminoff’s ‘Clinical Neurology’ Ninth edition ,page 153)Management

Avoidance of identified triggers or exacerbating factors (such as the combined contraceptive pill) may prevent attacks. Treatment of an acute attack consists of simple analgesia with aspirin, paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Nausea may require an antiemetic such as metoclopramide or domperidone. Severe attacks can be aborted by one of the ‘triptans’ (e.g. sumatriptan), which are potent 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT, serotonin) agonists. These can be administered via the oral, subcutaneous or nasal route. Caution is needed with ergotamine preparations because they may lead to dependence. Overuse of any analgesia, including triptans, may contribute to “medication overuse headache”.If attacks are frequent, or patient cannot tolerate acute medications or are contraindicated prophylaxis should be considered. Many drugs can be chosen but the most frequently used are vasoactive drugs (β-blockers), antidepressants (amitriptyline) and antiepileptic drugs (valproate, topiramate). Women with aura should avoid oestrogen treatment for either oral contraception or hormone replacement, although the increased risk of ischaemic stroke is minimal.

Finally, botulinium toxin (BOTOX), erenumab (Aimovig) and galcanezumab (Emgality); calcitonin gene-related peptides (CGRP) receptor monoclonal antibody, received approval from the US FDA for the prevention of chronic migraine.

CLUSTER HEADACHE

Cluster headaches are much less common than migraine. Unusually for headache syndromes, there is a significant male predominance and onset is usually in the third decade.Pathophysiology

The cause is unknown but this type of headache differs from migraine in many ways, suggesting a different pathophysiological basis. Although uncommon, it is the most common of the trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia syndromes. Functional imaging studies have suggested abnormal hypothalamic activity. Patients are more frequently smokers and higher than average alcoholconsumer.

Clinical features

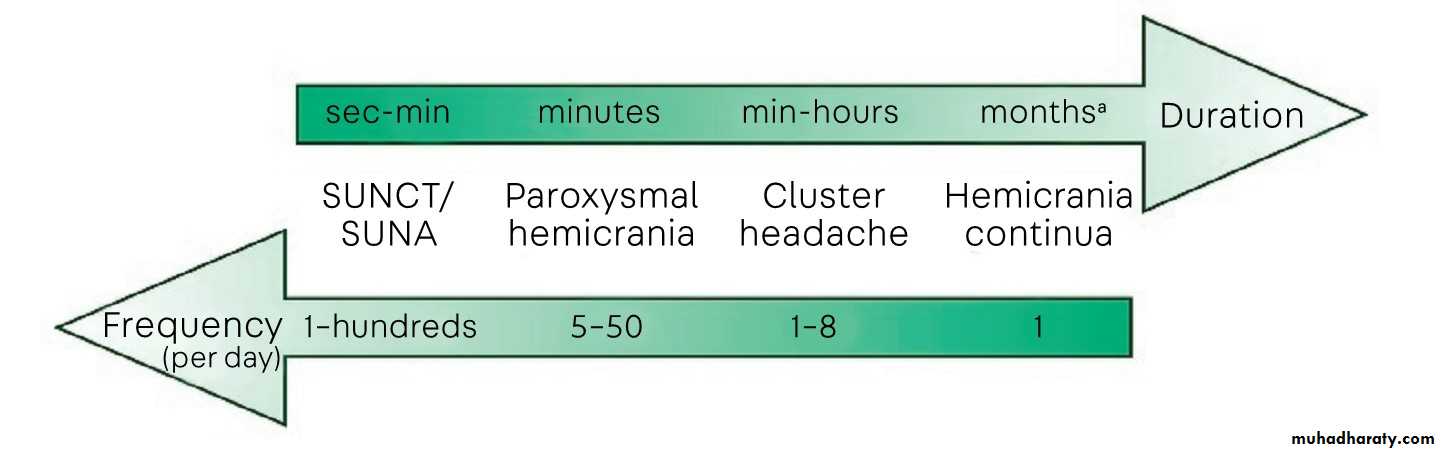

Cluster headache is strikingly periodic, presenting runs of identical headaches beginning at the same time for weeks (the ‘cluster’). Patients should experience at least five attacks of severe, unilateral periorbital pain lasting 15–180 minutes with either or both autonomic features; ipsilateral tearing, nasal congestion ,conjunctival injection (occasionally with the other features of a Horner’s syndrome) and a sense of restlessness or agitation. The attacks happen one every other day to eight attacks per day. They typically awake patient from sleep (‘alarm clock headache’). The cluster period is typically a few weeks, followed by remission for months to years (episodic variant), but a small proportion do not experience remission (chronic variant).Management

Acute attacks can usually be halted by subcutaneous injections of sumatriptan or inhalation of 100% oxygen. The brevity of the attack probably prevents other migraine therapies from being effective. Migraine prophylaxis is often ineffective too but attacks can be prevented in some patients by verapamil, sodium valproate, or short courses of oral glucocorticoids. Patients withsevere debilitating clusters can be helped with lithium therapy, although this requires monitoring.

Figure .2 Timing of individual attacks in trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias.

( Reprinted from CONTIUUM AUGUST 20 18 VOL. 24 NO. 4 , AAN)

PAROXYSMAL HEMICRANIA

It shares many features with cluster headache but is slightly shorter in the duration of attacks. In contrast to cluster headache, it is completely responsive to indometacin. It is less common than cluster headache with onset between 30 and 40 years of age. Unlike cluster headache, this disease may be slightly more common in women. Headache duration of 2 to 30 minutes and a frequency of greater than five attacks per day for half of the time the disease is active. In one study, the average duration was 26 minutes, and the average frequency was six per day, but up to 50 attacks per day have been reported.Short-lasting Unilateral Neuralgiform headache attacks with Conjunctival Injection and Tearing (SUNCT) And Short-lasting Unilateral Neuralgiform headache attacks With cranial Autonomic symptoms (SUNA)

These headaches are slightly more common in men. SUNCT and SUNA have identical diagnostic criteria with one exception: SUNCT always has the presence of both conjunctival injection and lacrimation, whereas SUNA may have one or neither of these features. Individual attacks are brief (1 to 600 seconds) and must occur once a day but usually occur much more frequently, up to hundreds of times per day. Tactile stimuli; touching the area of pain, chewing, or brushing the teeth may provoke an attack. The mainstay of treatment is lamotrigine.

TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA

This is characterised by unilateral lancinating facial pain, most commonly involving the second and/or third divisions of the trigeminal nerve territory, usually in patients over the age of50 years.

For most, trigeminal neuralgia remains an idiopathic condition but there is a suggestion that it may be due to an irritative lesion involving the trigeminal root entry zone, in some cases an aberrant loop of artery (classic). Other compressive lesions, usually benign, are occasionally found . Trigeminal neuralgia associated with multiple sclerosis may result from a plaque of demyelination in the brainstem (symptomatic).

Clinical features

The pain is repetitive, severe and very brief (seconds or less). It may be triggered by touch, a cold wind or eating. Physical signs are usually absent, although the spasms may make the patient wince and sit silently (tic douloureux). There is a tendency for the condition to remit and relapse over many years. Trigeminal neuralgia, however, lacks the prominent cranial autonomic features of SUNCT and SUNA. Furthermore, trigeminal neuralgia typically has a refractory period after an attack is triggered where no more attacks can be triggered by tactile stimuli for a brief time. SUNCT and SUNA typically do not have a refractory period.Management

Seventy percent of patients respond to carbamazepine. It is wise to start with a low dose and increase gradually, according to effect. In patients who cannot tolerate carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, gabapentin, pregabalin, amitriptyline or glucocorticoids may be effective alternatives, but if medication is ineffective or poorly tolerated, decompression of the vascular loop encroaching on the trigeminal root is said to have a 90% success rate. Otherwise, localised injection of alcohol or phenol into a peripheral branch of the nerve may be effective.HEADACHES ASSOCIATED WITH SPECIFIC ACTIVITIES

Primary sex headache

These usually affect men more than women in their thirties and forties. Patients develop a sudden, severe headache with sexual activity. There is usually no vomiting or neck stiffness, and the headache lasts less than 10–15 minutes, though a less severe dullness may persist for some hours. Subarachnoid haemorrhage needs to be excluded by CT and/or CSF examination after a first event. The pathogenesis of these headaches is unknown. Although frightening, attacks are usually brief and patients may need only reassurance and simple analgesia for the residual headache. The syndrome may recur, and prevention may be necessary with propranolol or indometacin.

Primary cough headache

Primary cough headache is a benign headache precipitated by coughing or straining that is not attributed to a secondary cause, such as an intracranial lesion. The most essential first step is to rule out a secondary cause based on red flags identified on history and examination. It is more common in women (64%) compared to men, with an average age of onset of 60 years of age(range of 22 to 80 years of age). Since it is benign and attacks of short duration, often reassurance is the only treatment needed.Primary exercise headache

It is a benign primary headache disorder that was previously termed ‘primary exertional headache’. It is unique in that it is precipitated by sustained physically strenuous activity rather than short-duration precipitating factors such as cough, Valsalva maneuver, or orgasm. Given the high prevalence in athletes, primary exercise headache should be considered when evaluating an athlete with headache. Primary exercise headache is an indometacin-responsive headache. Indometacin can be taken on a scheduled basis or prior to exercise. For patients who do not respond to or are unable to tolerate indomethacin, beta-blockers such as nadolol or propranolol have been effective.Ice cream headache

headache attributed to ingestion or inhalation of a cold stimulus, there must be at least two episodes of acute frontal , temporal or occipital headache brought on by and occurring immediately after a cold stimulus to the palate and/or posterior pharyngeal wall that resolve within 10 minutes after removal of the cold stimulus. Most importantly, these headaches are benign and short lasting, thus the abstinence of ingesting cold substances, such as ice cream, is not necessary or recommended just savor it slowly.Primary stabbing headache ’ icepick headache’:

primary stabbing headache, each stab must last for up to a few seconds and occur at an irregular frequency, from a single stab to a series of stabs and from one to many episodes per day. No cranial autonomic features are present. Clinically, primary stabbing headaches are headaches with the shortest duration. Idiopathic primary stabbing headache is benign and typically does not require any specific treatment aside from reassurance. However, if the stabbing pains are more frequent, indometacin is the medication of choice.Hypnic headache

Itis a primary headache disorder of short duration that typically occurs in elderly, typically after the age of 50. Diagnostic criteria include recurrent headaches lasting 15 minutes to 4 hours that develop only during sleep, cause awakening, and occur on 10 or more days per month for more than 3 months. Treatment options for hypnic headache include caffeine (100 mg to 200 mg), melatonin (3 mg to 12 mg), or lithium (200 mg to 600 mg); these medications should be given prior to bedtime.1- What are ‘red flag features’ in patient presenting with headache

2- Compare between SUNCT and trigeminal neuralgia.3- A 50 yrs old male pt presented with daily headache at 4 a.m . Give 3 differential diagnoses.

THANK YOU