SECONDARY HEADACHE SYNDROMES

Dr. Omar A. MahmoodOBJECTIVES

• To classify seconday causes of headache• To understand pathophsiology , clinical features of some secondary headaches

• To differentiate between different symptoms of secondary headache.

ETIOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION

• Vascular syndrome (SAH,ICH,ischemic stroke, CVT,cardiac cephalalgia,arterial hypertension, subdural hematoma)• Infective /inflammatory ( meningitis, encephalitis, abcess, temporal arteritis, etc).

• Tumour ( meningioma, low grade glioma, secondary, metastasis, etc)

• Iatrogenic ( medication overuse headache)

• Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, spontaneous intracranial hypotension

• Seizure

• Trauma

• Referred pain from other structures (sinus headache, orbit, temporomandibular joint, neck)

SABARACHNOID HAEMORRHAGE

Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is less common than ischaemic stroke or intracerebral haemorrhage. Women are affected more

commonly than men and the condition usually presents before the age of 65. The immediate mortality of aneurysmal SAH is about 30%; survivors have a recurrence (or rebleed) rate of about 40% in the first 4 weeks and 3% annually thereafter.

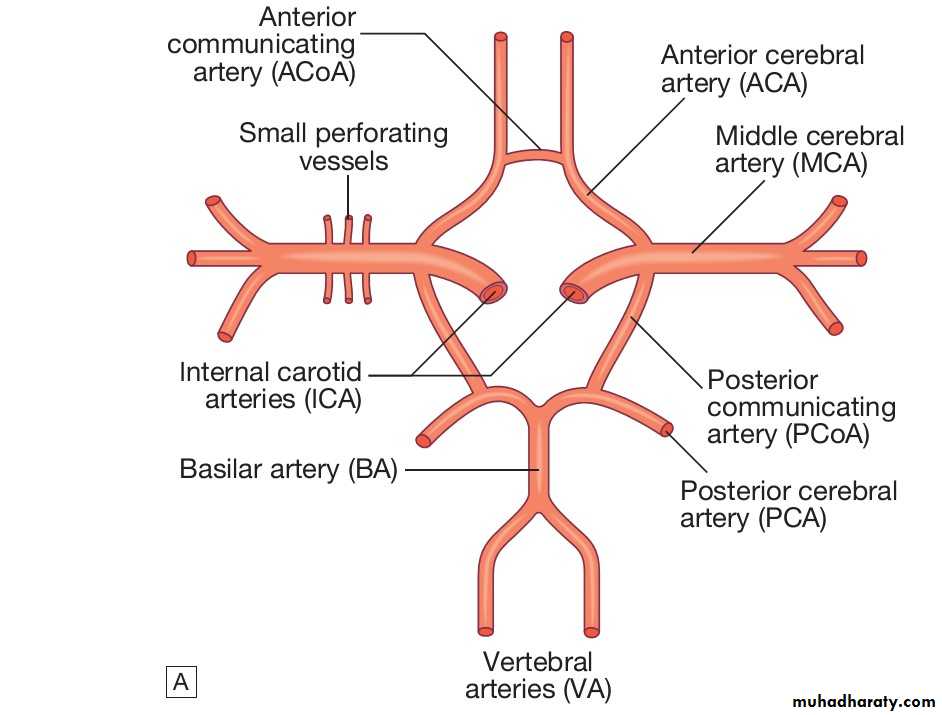

Some 85% of cases of SAH are caused by saccular or ‘berry’ aneurysms in the circle of Willis. The most common sites are in the anterior communicating artery (30%), posterior communicating artery (25%) or middle cerebral artery (20%), see figure 1. Around 5% of SAHs are due to arteriovenous malformations and vertebral artery dissection.

Clinical features

SAH typically presents with a sudden, severe, ‘thunderclap’ headache (often occipital), which lasts for hours or even days, often accompanied by vomiting, raised blood pressure and neck stiffness or pain. It commonly occurs on physical exertion, straining and sexual excitement. There may be loss of consciousness at the onset, so SAH should be considered if a patient is found comatose. About 1 patient in 8 with a sudden severe headache has SAH.Figure 1. Circle of Willis

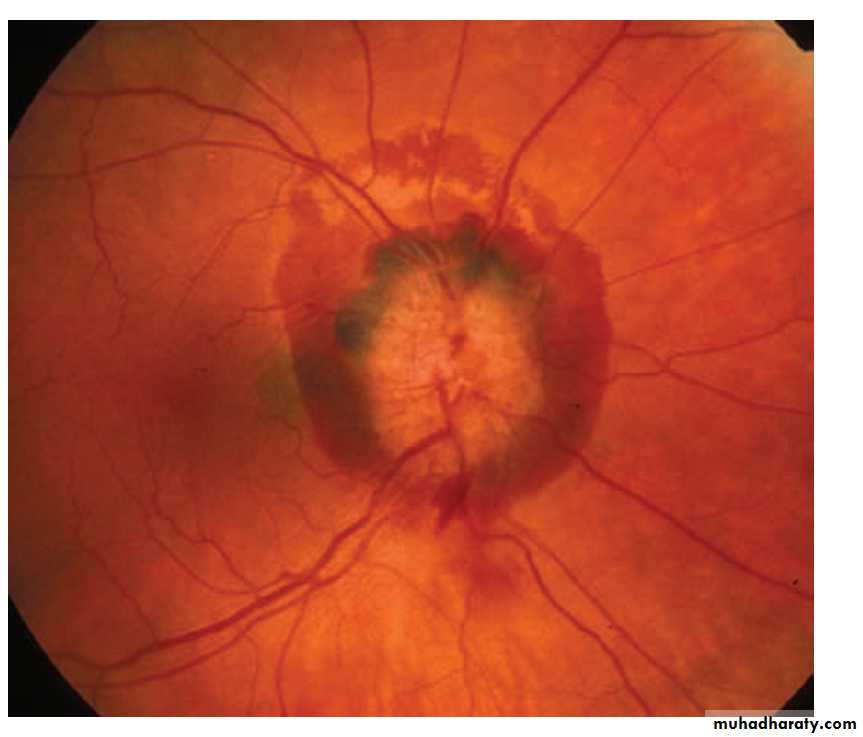

(Reprinted from Davidson principles and practice of medicine,23 rd edition)On examination, the patient is usually distressed and irritable, with photophobia. There may be neck stiffness due to subarachnoid blood but this may take some hours to develop. Focal hemisphere signs, such as hemiparesis or aphasia, may bepresent at onset if there is an associated intracerebral haematoma. A third nerve palsy may be present due to local pressure from an aneurysm of the posterior communicating artery, but this is rare. Fundoscopy may reveal a subhyaloid haemorrhage, which

represents blood tracking along the subarachnoid space around the optic nerve (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Fundoscopy shows subhyaloid haemorrhage.

(Reprinted from Amioff’s ‘Clinical Neurology’ 9th edition , page 139.Investigations

CT brain scanning and lumbar puncture are required. The diagnosis of SAH can be made by CT but a negative result does not completely exclude it, since small amounts of blood in the subarachnoid space cannot be detected by CT . Lumbar puncture should be performed 12 hours after symptom onset if possible, to allow detection of xanthochromia. If either of these tests is positive, cerebral angiography is required to determine the optimal approach toprevent recurrent bleeding.

CEREBRAL VENOUS DISEASE

Thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses is much less common than arterial thrombosis. However, it has been recognised with increasing frequency in recent years, as access to non-invasive imaging of the venous sinuses using MR venography has increased.Clinical features

Headache is the most common but least specific feature of cerebral venous thrombosis, presentin approximately 75%to 90%of cases. Headache is of thundercluap nature. Other features include focal cortical deficits such as aphasia and hemiparesis, seizure and papilledema. Risk factors for cerebral venous thrombosis include female sex, pregnancy or postpartum state and use of estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives.

INTRACEREBRAL HEMORRHAGE

Intracerebral hemorrhage commonly presents with headache, vomiting, altered consciousness, and focal neurologic deficits. Headache in this setting results from compression of pain-sensitive structures by the hematoma. The most common cause of nontraumatic intracerebral hemorrhageis hypertension, but AVMs and bleeding into tumors can present in a similar manner. The CT scan shows a hematoma, which is usually located in the basal ganglia, thalamus, cerebellum, pons, or subcortical white matter.

CEREBRAL ISCHEMIA

Headache occurs at onset of stroke or TIA in one-third of patients and may persist for hours to several days. The association of headache is independent of stroke etiology (thrombotic, embolic, lacunar), stroke severity, or hypertension. Headaches associated with ischemic stroke are typically mild to moderate in intensity, and nonthrobbing in character. Carotid lesions usually produce frontal pain, whereas posterior fossa strokes usually present with occipital headache. It should be noted that migraine with aura is also associated with an increased risk of strokeARTERIAL HYPERTENSION

• Headache that is precipitated by a hypertensive crisis, defined as a paroxysmal rise in systolic (to 180 mm Hg or more) and/or diastolic (to 120 mm Hg or more) blood pressure, may occur with or without symptoms of encephalopathy (eg, lethargy, confusion, visual disturbances or seizure). There must be temporal evidence of causation, with development of the headache at the onset of hypertension, significant worsening of the headache in parallel with worsening hypertension, and/or significant improvement of the headache with resolution of hypertension. The nature of such a headache is typically bilateral or diffuse, pulsating, and aggravated by physical activity.CARDIAC CEPHALALGIA

Cardiac cephalalgia refers to a headache that occurs in temporal relation to the onset of acute myocardial ischemia, is typically exacerbated by exertion and is relieved by treatments for acute coronary syndrome such as nitroglycerinor surgical interventions including angioplasty or coronary artery bypass grafting. Headache features can vary in location (bifrontal, bitemporal, oroccipital), intensity (mild to severe), and duration (minutes to hours); nausea may also accompany the headache, which may sometimes resemble migraine.

HEADACHE SECONDARY TO INFECTION/INFLAMAMTION

Patients presenting with headache associated with fever, nuchal stiffness, Kernig and Brudzinski signs warrant further evaluation with head imaging followed by lumbar puncture (if not contraindicated) to rule out an infectious or inflammatory meningitis. Meningitis can be mistaken for migraine given the common symptoms of throbbing headache, photophobia, nausea, and vomiting, perhaps reflecting the underlying physiology in some cases. Systemic bacterial and viral infections may also cause headache, typically of moderate to severe intensity and diffuse/holocranial in location, which develops in temporal relation to the onset of the infection and improves in parallel with its resolution.GIANT CELL ARTERITIS (TEMPORAL ARTERITIS)

Onset of headache at or past the age of 50, with associated tenderness of the temporal artery or shallow temporal artery pulsations, should raise concern for giant cell arteritis. It is most frequently seen in the elderly population, with an average age of onset of 70 years, with a female predominance. Blindness can be a complication of untreated temporal arteritis in approximately half of patients due to involvement of the ophthalmic artery and its branches; however, visual loss can be preventedWith prompt glucocorticoid treatment.

Headache is the most common presenting symptom, which can be unilateral or bilateral and is often temporally located but can occur in any cranial region. The quality of the headache is generally dull and aching, although patients may experience intermittent stabbing pains superimposed on the background headache and report scalp tenderness. The headache is usually worse at night and can be aggravated by exposure to cold. Associated symptoms include jaw claudication, myalgia, unexplained weight loss, and malaise, fever , arthralgia (polymyalgia rheumatica).

In suspected cases, an ESR or CRP should be checked, and a temporal artery biopsy should be completed for diagnostic confirmation. Headache generally resolves or significantly improves within 3 days of treatment initiation with high-dose glucocorticoids.

HEADACHE DUE TO TUMORS

• Headaches associated with brain tumors are most often nonspecific in character, mild to moderate in severity, dull and steady in nature, and intermittent. The pain is characteristically bifrontal, worse ipsilaterally, and aggravated by a change in position or by maneuvers that increase intracranial pressure, such as coughing, sneezing, and straining at stool. The headache is classically maximal on awakening in the morning and is associated with nausea and vomiting.Suspicion of an intracranial mass lesion demands

prompt evaluation by CT scan or MRI. Brain tumor isexcluded by a normal contrast-enhanced brain MRI scan. Tumor treatment depends on the histologic type (benign or malignant, primary or metastatic, pathologic grade), but may include surgical excision, radiation, and chemotherapy. Prognosis also varies with tumor characteristics, age, biomarkers, and gene polymorphisms.

MEDICATION OVERUSE HEADACHE

Simple analgesics are overused if taken on 15 or more days per month (regardless of the reason for taking the medication), whereas triptans, dihydroergotamine, combination analgesics, opiates, and combinations of medications from different medication classes are overused when taken on 10 or more days per month. Despite these definitions, it is likely that intake of butalbital-containing medications or opiates on fewer than 10 days per month still increases the risk of developing more frequent headaches, and thus their use should be severely limited or avoided altogether.

Management is by withdrawal of the responsible analgesics. Patients should be warned that the initial effect will be to exacerbate the headache, and migraine prophylactics may be helpful in reducing the rebound headaches. Relapse rates are high, and patients often need help and support in withdrawing from analgesia; a careful explanation of this paradoxical concept is vital.

IDIOPATHIC INTRACRANIAL HYPERTENSION

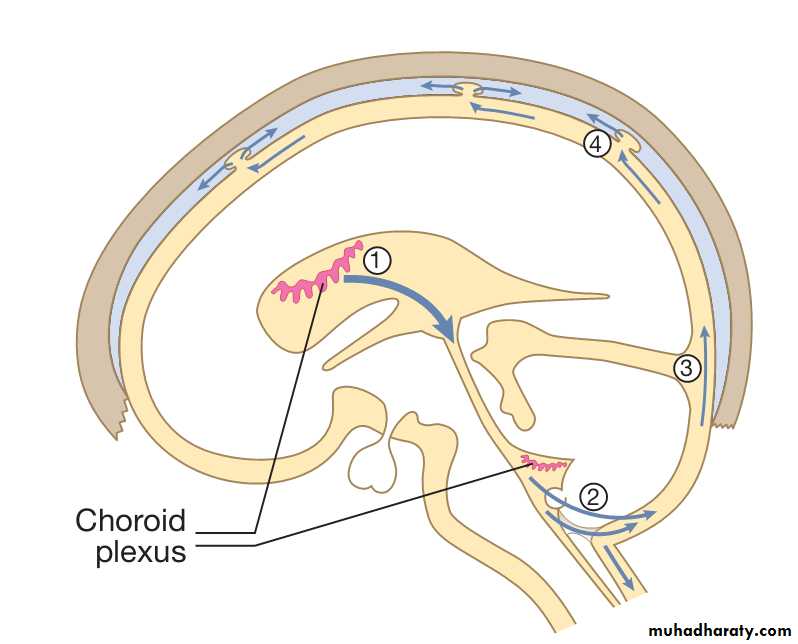

This usually occurs in obese young women. Raised ICP occurs in the absence of a structural lesion, hydrocephalus or other identifiable cause. The aetiology is uncertain but there is an association with obesity in females, perhaps inducing a defect of CSF reabsorption by the arachnoid villi (See figure 3). A number of drugs may be associated, including tetracycline, vitamin A and retinoid derivatives.Figure 3. The circulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

(Reprinted from Davidson principles and practice of medicine,23 rd edition)The usual presentation is with headache, sometimes accompanied by diplopia and visual disturbance (most commonly, transient obscurations of vision associated with changes in posture). Clinical examination reveals papilloedema but little else. False localising cranial nerve palsies (usually of the 6th nerve) may be present. It is important to record visual fields accurately for

future monitoring.

Brain imaging is required to exclude a structural or other cause. The ventricles are typically normal in size or small (‘slit’ ventricles). The diagnosis may be confirmed by lumbar puncture, which shows raised normal CSF constituents at increased pressure (usually >300 mmH2O CSF). Management can be difficult and there is no evidence to support any specific treatment. Weight loss in overweight patients may be helpful if it can be achieved. Acetazolamide or topiramate may help to lower intracranial pressure, the latter perhaps aiding weight loss in some patients. Repeated lumbar puncture is an effective treatment for headache but may be technically difficult in obese individuals and is often poorly tolerated. Patients failing to respond, in whom chronic papilloedema threatens vision, may require optic nerve sheath fenestration or a lumbo-peritoneal shunt.

LOW-PRESSURE HEADACHE SYNDROMES

Post–lumbar-puncture headache is diagnosed by a history of a dural puncture (eg, spinal tap, spinal anesthesia) and is characteristically a postural headache, with marked increase in pain in the upright position and relief with recumbency. The pain is typically occipital, comes on within 48 to 72 hours after the procedure, and lasts 1 to 2 days. Nausea and vomiting may occur. Headache is caused by persistent leak of CSF from the spinal subarachnoid space, with resultant traction on pain-sensitive structures at the base of the brain.Low-pressure headache syndromes are usually self-limited. When this is not the case, they may respond to the administration of caffeine sodium benzoate, which can be repeated after 45 minutes if headache persists or recurs upon standing. In persistent cases, the subarachnoid rent can be sealed by injection of autologous blood into the epidural space at the site of the puncture; this requires an experienced anesthesiologist.

SPONTANEOUS INTRACRANIAL HYPOTENSION

It can produce headache similar in character to that caused by lumbar puncture. Diagnosis usually by demonstrtion of leak or MRI finding of subdural fluid collection, T1-weighted, gadolinium-enhanced pachymeninges and a “sagging brain” with 2 of 3: (low CSF pressure ‘<60mm H2O’ , spinal meningeal diverticulum or improvement of symptoms with autologous epidural blood patch). the enhancement may be confused with that associated with meningitis. Low CSF pressure can produce the same MRI picture in the absence of headache.SEIZURES

Preictal, ictal, and postictal headaches occur but only the latter are common; they are associated most often with generalized tonic-clonic seizures but also occur following seizures of simple and complex partial phenomenology. Migrainous features (throbbing, nausea and vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia) are common and similar to patients’ non-ictal headaches. It may be important to differentiate these headaches from those of subarachnoid hemorrhage or meningitis. If doubt exists about the cause, lumbar puncture should be undertaken: seizures may produce a mild CSF pleocytosis (up to approximately 10 cells/μL after single seizures or up to approximately 100 cells/μL after status epilepticus), but CSF glucose content is normal.TRAUMA

To be categorized as posttraumatic headache, the onset must occur within 7 days of injury to the head orwithin 7 days of regaining consciousness following the event or of cessation of any medications that could potentially interfere with the patient’s perception of the headache. Headache during the first 3 months after onset is considered to be acute and is categorized as persistent if lasting beyond that period.The phenotype of posttraumatic headache can vary, although most often is migrainous; tension-type headache is also commonly reported. Other accompanying symptoms can include dizziness, fatigue, cognitive difficulties, anxiety, insomnia, and personality changes. The treatment of posttraumatic headache is empiric, usually directed toward the presenting phenotype of the headache. The headache usually resolves within 3–5 years, but it can be quite disabling.

‘SINUS’ HEADACHE

The occurrence of cranial autonomic symptoms in migraine (lacrimation, nasal congestion, and rhinorrhea) may contribute to the misdiagnosis of “sinus headache”. diagnostic criteria for headache attributed to acute rhinosinusitis requires clinical, nasal endoscopic, and/or imaging evidence of acute rhinosinusitis, as well as at least two of the following:• establishment of a time relation of pain to the onset of rhinosinusitis,

• either reduction or exacerbation of pain symptoms matching improvement or worsening of rhinosinusitis symptoms,

• increase of pain upon application of pressure over the sinuses,

• ipsilateral pain in the case of unilateral rhinosinusitis.

The pain of acute sinusitis is often characterized as deep pressure, fullness or congestion in the face, and is frequently worsened with lying down. Sinusitis is treated with vasoconstrictor nasal drops, antihistamines, and antibiotics. In refractory cases, surgical sinus drainage may be necessary.

ACUTE ANGLE-CLOSURE GLAUCOMA

Severe headache and eye pain can result from intermittent angle-closure glaucoma, whereby acute obstruction of aqueous humor at the drainage angle of the eye leads to a significant rise in intraocular pressure. Intermittent angle-closure glaucoma may be mistaken for migraine, as both conditions can present with unilateral eye pain, nausea/vomiting, light sensitivity, and visual disturbances including blurred vision as well as rainbow-colored halos around lights. On examination, the eye is often injected with a fixed,moderately dilated pupil. However, between attacks, eye appearance and intraocular pressures are usually normal. Triggers for angle closure include sudden contrast in lighting conditions, prolonged reading, and use of specific medications (including some cold/allergy drugs with adrenergic agonist effects, certain anticholinergic medications and some sulfa-based agents such as topiramate and acetazolamide). Patients with suspected acute angle-closure glaucoma should be referred urgently to ophthalmology for slit-lamp and gonioscopic examination.TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT DYSFUNCTION

It is a poorly defined syndrome characterized by preauricular facial pain, limitation of jaw movement, tenderness of the muscles of mastication, and “clicking” of the jaw with movement. Symptoms are often associated with malocclusion, bruxism, or clenching of the teeth and may result from spasm of the masticatory muscles. Some patients benefit from local application of heat, jaw exercises, nocturnal use of a bite guard, or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

CERVICAL SPINE DISEASE

Injury or degenerative disease processes involving theupper neck can produce pain in the occiput or orbital

regions. The most important source of discomfort is irritation of the second cervical (C2) nerve root. Disk disease or abnormalities of the articular processes affecting the lower cervical spine refer pain to the ipsilateral arm or shoulder, not to the head, although cervical muscle spasm may occur. Acute pain of cervical origin is treated with immobilization of the neck (eg, with a soft collar) and analgesic or anti-inflammatory drugs.

QUESTIONS

1. Enumerate the common causes of secondary headache syndrome and discuss one cause.2. Discuss the difference between migraine headache and acute closure angle glaucoma headache

3. What are common causes of chronic daily headache.