SERONEGATIVE SPONDYLOARTHROPATHIESpart 2

Dr. Ali Abdul-Rahman YounisRHEUMATOLOGIST(FIBMS)

Reactive arthritis

Reactive (spondylo)arthritis (ReA) is a ‘reaction’ to a number of bacterial triggers with clinical features in keeping with all SpA conditions.The known triggers are Chlamydia, Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia.

Non-SpA-related reactive arthritis can occur following infection with many viruses, Mycoplasma, Borrelia, streptococci and mycobacteria, including M. leprae; however, the ‘reaction’ in these instances consists typically of myoarthralgias, is not associated with HLA-B27 and is generally not chronic.

The arthritis associated with rheumatic fever is also an example of a reactive arthritis that is not associated with HLA-B27.

Reactive arthritis

Sexually acquired reactive arthritis (SARA) is predominantly a disease of young men, with a male preponderance of 15 : 1.This may reflect a difficulty in diagnosing the condition in young women, in whom Chlamydia infection is often asymptomatic and is hard to detect in practical terms.

Between 1% and 2% of patients with non-specific urethritis seen at genitourinary medicine clinics have SARA.

The syndrome of chlamydial urethritis, conjunctivitis and reactive arthritis was formerly known as Reiter’s disease.

With enteric triggering infections (enteropathic ReA), HLA-B27 may predict the reactive arthritis and its severity, though the condition occurs in HLA-B27-negative people.

Clinical features

The onset is typically acute, with an inflammatory enthesitis, oligoarthritis and/or spinal inflammation.Lower limb joints and entheses are predominantly affected.

In all types of ReA, there may be considerable systemic disturbance, with fever and weight loss.

Achilles insertional enthesitis/tendonitis or plantar fasciitis may also be present.

The first attack of arthritis is usually self-limiting, but recurrent or chronic arthritis can develop and about 10% still have active disease 20 years after the initial presentation.

Low back pain and stiffness due to enthesitis and osteitis are common and 15–20% of patients develop sacroiliitis.

Clinical features

Many extra-articular features in ReA involve the skin, especially in SARA:

Circinate balanitis, which starts as vesicles on the coronal margin of the prepuce and glans penis, later rupturing to form supericial erosions with minimal surrounding erythema, some coalescing to give a circular pattern

Keratoderma blennorrhagica, which begins as discrete waxy, yellow–brown vesico-papules with desquamating margins, occasionally coalescing to form large crusty plaques on the palms and soles of the feet

Pustular psoriasis

Nail dystrophy with subungual hyperkeratosis

Mouth ulcers

Conjunctivitis

Uveitis, which is rare with the first attack but arises in 30% of patients with recurring or chronic arthritis.

Clinical features

Other complications in ReA are very rare but include aortic incompetence, conduction defects, pleuro-pericarditis, peripheral neuropathy, seizures and meningoencephalitis.Investigations

The diagnosis is usually made clinically but joint aspiration may be required to exclude crystal arthritis and articular infection.Synovial fluid is leucocyte rich and may contain multinucleated macrophages (Reiter’s cells).

ESR and CRP are raised during an acute attack.

Urethritis may be confirmed in the ‘two glass test’ by demonstration of mucoid threads in the first void specimen that clear in the second.

High vaginal swabs may reveal Chlamydia on culture.

Except for post-Salmonella arthritis, stool cultures are usually negative by the time the arthritis presents, but serum agglutinin tests may help confirm previous dysentery.

RF, ACPA and ANA are negative.

Investigations

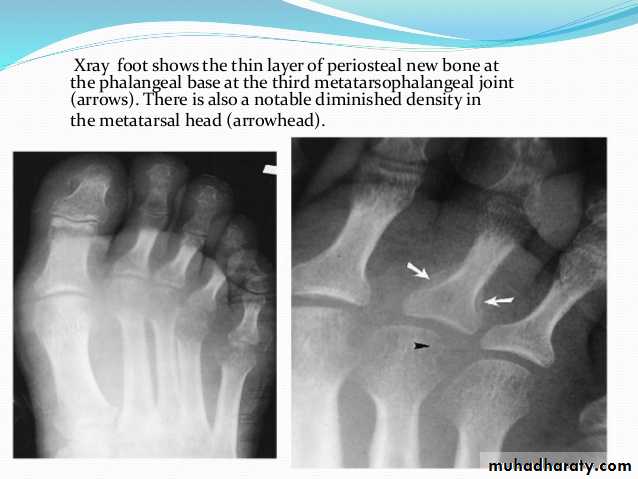

In chronic or recurrent disease, X-rays show joint space narrowing and proliferative erosions.Another characteristic feature is periostitis, especially of metatarsals, phalanges and pelvis, and large, ‘fluffy’ calcaneal spurs.

In contrast to AS, radiographic sacroiliitis is often asymmetrical and sometimes unilateral, and syndesmophytes are predominantly coarse and asymmetrical, often extending beyond the contours of the annulus (‘nonmarginal’)

X-ray changes in the peripheral joints and spine are identical to those in psoriatic arthritis.

Management

The acute attack should be treated with rest, oral NSAIDs and analgesics.Intraarticular steroids may be required in patients with severe synovitis.

Nonspecific chlamydial urethritis is usually treated with a short course of doxycycline or a single dose of azithromycin, and this may reduce the frequency of arthritis in sexually acquired cases.

Treatment with DMARDs (usually sulfasalazine or methotrexate) should be considered for patients with persistent marked symptoms, recurrent arthritis or severe keratoderma blennorrhagica.

Anterior uveitis is a medical emergency requiring topical, subconjunctival or systemic corticosteroids.

For DMARD-recalcitrant cases, anti-TNF therapy should be considered.

Psoriatic arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) occurs in 7–20% of patients with psoriasis and in up to 0.6% of the general population.The onset is usually between 25 and 40 years of age.

Most patients (70%) have preexisting psoriasis but in 20% the arthritis predates the occurrence of skin disease. Occasionally, the arthritis and psoriasis develop synchronously.

Pathophysiology

Genetic factors have an important role in PsA and family studies have suggested that heritability may exceed 80%.

Variants in the HLA-B and HLA-C genes are the strongest genetic risk factors.

It is thought that an environmental trigger, probably infectious in nature, triggers the disease in genetically susceptible individuals, leading to immune activation involving dendritic cells and T cells.

Pathophysiology

There is increasing evidence that the IL-23/IL-17 pathway plays a pivotal role in PsA. It is thought that the triggering stimulus causes over-production of IL-23 by dendritic cells, which in turn promotes differentiation and activation of Th17 cells, which produce the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17A.This, along with Th1 cytokines like IFN-γ and TNF-α, acts on macrophages and tissue-resident stromal cells at entheses, in bone and within the joint to produce additional pro-inflammatory cytokines and other mediators, which contribute to inflammation and tissue damage

Clinical features

The presentation is with pain and stiffness affecting joints, tendons, spine and entheses. Joints are typically not swollen.Several patterns of joint involvement are recognised including an oligoarticular form. These patterns are not mutually exclusive.

Marked variation in disease patterns exists, including a disease course of intermittent exacerbation and remission.

Destructive arthritis and disability are uncommon, except in the case of arthritis mutilans.

Asymmetrical inflammatory oligoarthritis

Affects about 40% of patients and often presents abruptly with a combination of synovitis and adjacent periarticular inflammation.This occurs most characteristically in the hands and feet, when synovitis of a finger or toe is coupled with tenosynovitis, enthesitis and inflammation of intervening tissue to give a ‘sausage digit’ or dactylitis.

Large joints, such as the knee and ankle, may also be involved, sometimes with very large effusions.

Symmetrical polyarthritis

Occurs in about 25% of cases.

It predominates in women and may strongly resemble RA, with symmetrical involvement of small and large joints in both upper and lower limbs.

Nodules and other extraarticular features of RA are absent and arthritis is generally less extensive and more benign.

Much of the hand deformity often results from tenosynovitis and soft tissue contractures.

Distal interphalangeal joint arthritis

This is quite a common pattern and can be difficult to distinguish from inflammatory generalized OA. PsA DIP joint disease is associated with psoriatic nail disease.Psoriatic spondylitis

This type presents with inflammatory back or neck pain and prominent stiffness symptoms.Any structure in the spine can be involved, including intervertebral disc, entheses ,and facet joints.

It may occur alone or with any of the other clinical patterns described above and is typically unilateral or asymmetric in severity.

Arthritis mutilans

This is a deforming erosive arthritis targeting the fingers and toes; it occurs in 5% of cases of PsA.Prominent cartilage and bone destruction results in marked instability.

The encasing skin appears invaginated and ‘telescoped’ and the finger can be pulled back to its original length.

Enthesitis-predominant

This form of disease presents with pain and stiffness at the insertion sites of tendons and ligaments into bone (enthesitis).Symptoms can be extensive or localised.

Typically affected entheses include Achilles tendon insertions, plantar fascia origins, patellar ligament attachments, hip abductor complex insertion at lateral femoral condyle, gluteus medius insertion at greater trochanter, humeral epicondyle tendon attachments, deltoid origin at acromial edge, intercostal muscle attachments at ribs, and pelvic ligament attachments.

Extra-articular features

Nail changes include pitting, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis and horizontal ridging, which are found in 85% of patients with PsA and can occur in the absence of skin disease.The characteristic rash of psoriasis may be widespread, or confined to the scalp, natal cleft, umbilicus and genitals, where it is easily overlooked.

Obtaining a history of psoriasis in a first-degree relative can be tricky but is important, given that a positive response contributes to making a diagnosis.

Investigations

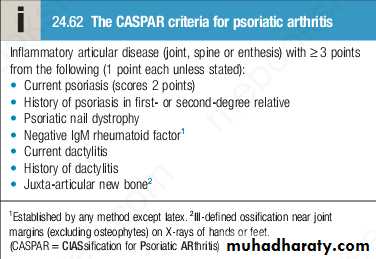

The diagnosis is made on clinical grounds.Autoantibodies are generally negative and acute phase reactants, such as ESR and CRP, are raised in only a proportion of patients with active disease.

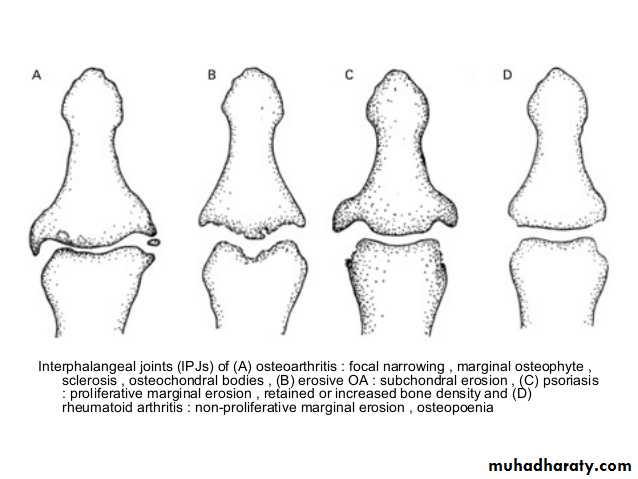

X-rays may be normal or show erosive change with joint space narrowing. Features that favour PsA over RA include the characteristic distribution of proliferative erosions with marked new bone formation, absence of periarticular osteoporosis .

Imaging of the axial skeleton often reveals features similar to those in chronic reactive arthritis, with coarse, asymmetrical, nonmarginal syndesmophytes and asymmetrical sacroiliitis.

MRI and ultrasound with power Doppler are increasingly employed to detect synovial inflammation and inflammation at the entheses.

Management

Therapy with NSAID and analgesics may be sufficient to control symptoms in mild disease.Intraarticular steroid injections can control synovitis in problem joints.

Splints and prolonged rest should be avoided because of the tendency to fibrous and bony ankylosis.

Patients with spondylitis should be prescribed the same exercise and posture regime as in AS.

Management

Therapy with DMARDs should be considered for persistent synovitis unresponsive to conservative treatment. Methotrexate is the drug of first choice since it may also help skin psoriasis, but other DMARDs may also be effective, including sulfasalazine, ciclosporin and leflunomide.DMARD monitoring should take place with particular attention to liver function since abnormalities are common in PsA.

Hydroxychloroquine is generally avoided, as it can cause exfoliative skin reactions.

AntiTNF treatment should be considered for patients with active synovitis who respond inadequately to standard DMARDs. This is effective for both PsA and psoriasis.

Management

Ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds to and neutralises the p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23, improves joint, dactylitis and enthesitis lesions in PsA.Secukinumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-17A, has similar efficacy to TNF inhibitors in PsA.

Apremilast is an oral small-molecule inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4), which is effective in PsA when DMARD therapy fails, although it appears to be less efficacious than biologic treatment. Adverse effects include weight loss, depression and suicidal ideation.

Enteropathic (spondylo)arthritis

The overall prevalence of inflammatory musculoskeletal disease in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) is not well known, as studies have not adequately assessed enthesitis and osteitis lesions, but the musculoskeletal manifestations are in keeping with an SpA phenotype.Involvement of the peripheral joints is seen in about 20% of IBD patients.

Oligoarticular disease predominantly affects the large lower limb joints (knees, ankles and hips).

Radiographic evidence of sacroiliitis is present in about 20–25% of IBD patients.

Enteropathic (spondylo)arthritis

In Crohn’s disease, more than in colitis, the arthritis usually coincides with exacerbations of the underlying bowel disease and the arthritis improves with effective treatment of the bowel disease.

There is some suggestion that the severity and onset of inflammatory musculoskeletal symptoms can vary in association with changes in the integrity of the ileocaecal valve, raising the possibility that changes in gut flora may act as triggers for the associated SpA.

Enteropathic (spondylo)arthritis

NSAIDs are best avoided, since they can exacerbate IBD.Instead, judicious use of glucocorticoids, sulfasalazine and methotrexate may be considered.

Liaison is necessary between gastroenterologist and rheumatologist with regard to choice of therapy.

Anti-TNF therapy is effective in enteropathic arthritis but etanercept should be avoided, as it has no efficacy in IBD.

When musculoskeletal symptoms worsen despite anti-TNF therapy, it is wise to exclude bacterial overgrowth as a triggering cause (blind-loop syndrome).