Autoimmune Connective Tissue DiseasesPart 3

Dr. Ali Abdul-Rahman YounisRHEUMATOLOGIST(FIBMS)

Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies

Rare connective tissue diseases defined by the presence of muscle weakness and inflammation.The etiology is unknown.

The most common clinical forms are polymyositis, dermatomyositis, Juvenile dermatomyositis and inclusion body myositis.

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis are related disorders that are characterized by an inflammatory process affecting skeletal muscle and (cardiac and gut) smooth muscle.In dermatomyositis, characteristic skin changes also occur.

Both diseases are rare, with an incidence of 2–10 cases per million/year.

They can occur in isolation or in association with other autoimmune diseases, such as SLE, systemic sclerosis and Sjögren’s syndrome.

The cause is unknown, although there is evidence for a genetic contribution.

Both are notably connected with (either previously diagnosed or undisclosed) malignancy.

Clinical features

The typical presentation of polymyositis is with symmetrical proximal muscle weakness, usually affecting the lower limbs more than the upper.The onset is usually between 40 and 60 years of age and is typically gradual, over a few weeks.

Myositis is usually widespread but focal disease can also occur.

Affected patients report difficulty rising from a chair, climbing stairs and lifting, sometimes in combination with muscle pain.

Systemic features of fever, weight loss and fatigue are common.

Respiratory or pharyngeal muscle involvement can lead to ventilatory failure or aspiration that requires urgent treatment.

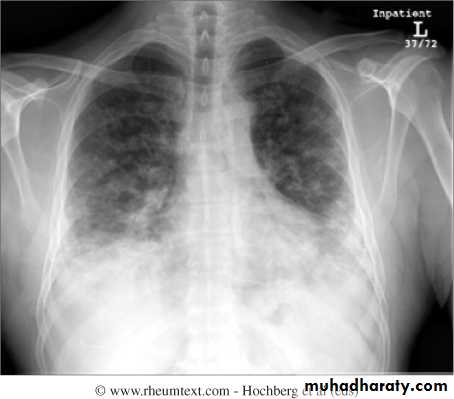

Interstitial lung disease occurs in up to 30% of patients and is strongly associated with the presence of antisynthetase (Jo1) antibodies.

Clinical features

Dermatomyositis presents similarly but in combination with characteristic skin lesions.

Gottron’s papules are scaly, erythematous or violaceous, psoriaform plaques occurring over the extensor surfaces of PIP and DIP joints.

Heliotrope rash is a violaceous discoloration of the eyelid in combination with periorbital oedema .

Similar rashes occur on the upper back, chest and shoulders (‘shawl’ distribution).

Periungual nailfold capillaries are often enlarged and tortuous.

Extra-muscular manifestation

Pulmonary –respiratory muscle weakness, aspiration, interstitial lung disease ,pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vasculitis.Cardiac –heart block ,arrhythmias and cardiomyopathy.

GIT –esophageal ,stomach ,small and large bowl dysmotility.

Arthritis –nonerosive ,symmetrical ,small joints.

Investigations

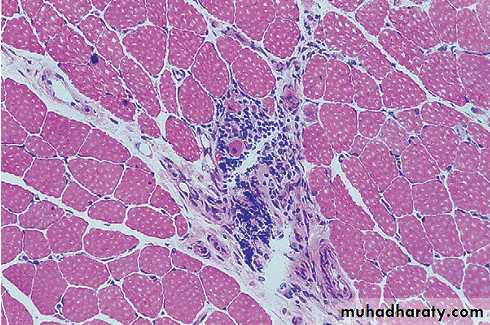

Muscle biopsy is the pivotal investigation and shows the typical features of fibre necrosis, regeneration and inflammatory cell infiltrate. Occasionally, however, a biopsy may be normal, particularly if myositis is patchy.In such cases, MRI is used to identify areas of abnormal muscle for biopsy.

Serum levels of CK are usually raised and are a useful measure of disease activity, although a normal CK does not exclude the diagnosis, particularly in juvenile myositis.

Investigations

EMG can confirm the presence of myopathy and exclude neuropathy.Screening for underlying malignancy should be undertaken routinely (full examination, chest X-ray, serum urine and protein electrophoresis, CT of chest/abdomen/pelvis; prostate-specific antigen should be included in men, and mammography in women).

Muscle biopsy from a patient with inflammatory myositis. The sample shows an intense inflammatory cell infiltrate in an area of degenerating and regenerating muscle fibres.

Management

Oral corticosteroids (prednisolone 1 mg/kg daily) are the mainstay of initial treatment, but high dose intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g/day for 3 days) may be required in patients with respiratory or pharyngeal weakness.

If there is a good response, steroids should be reduced by approximately 25% per month to a maintenance dose of 5–7.5 mg.

Although most patients respond well to corticosteroids, many need additional immunosuppressive therapy.

Methotrexate and MMF are the first choices of many but azathioprine and ciclosporin are also used as alternatives.

Rituximab appears to show efficacy in a majority of patients, although the only controlled study was negative. In clinical practice, rituximab is an option for use with glucocorticoids, to maintain an early glucocorticoid-induced remission

Management

Intravenous immunoglobulin may be effective in refractory cases.Mepacrine or hydroxychloroquine has been used for skin-predominant disease to some good effect in certain cases.

Relapses may occur in association with a rising CK, and indicate the need for additional therapy.

If the patient relapses or fails to respond to treatment, this may be due to steroid induced myopathy.

A further biopsy should be performed and may show type 2 fibre atrophy in steroid induced myopathy, as opposed to necrosis and regeneration in active myositis.

Inclusion body myositis

This is an inflammatory disease of muscle of unknown cause with a genetic component, which is associated with the accumulation of abnormal protein aggregates in affected tissue.It presents with muscle weakness in those over the age of 40 and is more common in men.

Although proximal weakness does occur, distal involvement is more usual and may be asymmetrical.

Investigation is the same as for polymyositis and typically reveals a slightly elevated CK and both myopathic and neurogenic changes on EMG. Muscle biopsy shows abnormal fibres containing rimmed vacuoles and filamentous inclusions in the nucleus and cytoplasm.

Treatment can be tried with high dose corticosteroids, immunosuppressants and immunoglobulin, , but the therapeutic response is often poor.

Juvenile dermatomyositis

Juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is by far the most common inflammatory myopathy in children and adolescents, and typically does not require a search for malignancy.

The incidence is 2–4 per million (USA and UK) with a median age of onset of 7 years (25% are below 4 years at diagnosis).

Many clinical features are similar to those in the adult disease.

JDM can be monocyclic, lasting up to 3 years (25–40%), or polycyclic, with periods of remission and relapse (60–75%). In some cases, polycyclic JDM can be chronic and life-long.

It is ulcerative in 10–20%. Calcinosis occurs in about 30%.

Intravenous methylprednisolone, then oral glucocorticoids and methotrexate produce a rapid response in many cases. Cyclophosphamide is used for lesional ulceration. IVIg is given in resistant case.

Mixed connective tissue disease

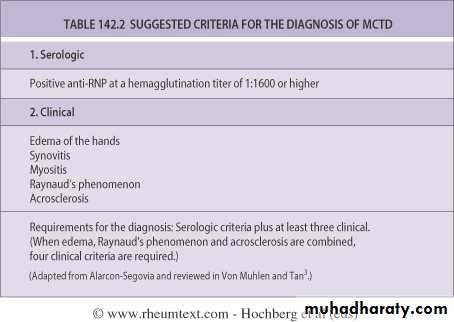

Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) is a condition in which the clinical features of SLE, systemic sclerosis and myositis may all occur in the same patient.It most commonly presents with synovitis and oedema of the hands, in combination with Raynaud’s phenomenon and muscle pain or weakness.

Most patients have antiribonucleoprotein (RNP) antibodies, but these can occur in SLE without overlap features.

Management focuses on treating the individual components of the syndrome.

Lab Features

High titer speckled ANAHigh titer anti RNP Ab

Negative anti-dsDNA Ab and anti-Sm Ab

Normal complement level

Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia

THANKS