1

Fifth stage

Medicine

Lec-9

د.بشار

15/12/2015

Intracerebral hemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage is focal bleeding from a blood vessel in the brain parenchyma.

The cause is usually hypertension. Typical symptoms include focal neurologic deficits, often

with abrupt onset of headache, nausea, and impairment of consciousness. Most

intracerebral hemorrhages occur in the basal ganglia, cerebral lobes, cerebellum, or pons.

Intracerebral hemorrhage may also occur in other parts of the brain stem or in the

midbrain.

Etiology

Intracerebral hemorrhage usually results from rupture of an arteriosclerotic small artery

that has been weakened, primarily by chronic arterial hypertension. Such hemorrhages are

usually large, single, and catastrophic. Other modifiable risk factors that contribute to

arteriosclerotic hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhages include cigarette smoking, obesity,

and a high-risk diet (eg, high in saturated fats, trans fats, and calories). Use of cocaine or,

occasionally, other sympathomimetic drugs can cause transient severe hypertension

leading to hemorrhage.

Less often, intracerebral hemorrhage results from congenital aneurysm, arteriovenous or

other vascular malformation ,trauma , mycotic aneurysm, brain infarct (hemorrhagic

infarction), primary or metastatic brain tumor, excessive anticoagulation, blood dyscrasia,

intracranial arterial dissection, moyamoya disease, or a bleeding or vasculitic disorder.

لالطالع فقط

Vascular Lesions in the Brain

Common brain vascular lesions include

arteriovenous malformations and

aneurysms.

Arteriovenous malformations

(AVMs):AVMs are tangled, dilated blood

vessels in which arteries flow directly into

veins. AVMs occur most often at the

junction of cerebral arteries, usually within

the parenchyma of the frontal-parietal

region, frontal lobe, lateral cerebellum, or

overlying occipital lobe. AVMs also can

occur within the dura. AVMs can bleed or

directly compress brain tissue; seizures or

ischemia may result.

Many aneurysms are

asymptomatic, but a few cause

symptoms by compressing adjacent

structures. Ocular palsies, diplopia,

squint, or orbital pain may indicate

pressure on the 3rd, 4th, 5th, or 6th

cranial nerves. Visual loss and a

bitemporal field defect may

indicate pressure on the optic

chiasm. Aneurysms may bleed into

the subarachnoid space, causing

subarachnoid hemorrhage. Before

rupture, aneurysms occasionally

cause sentinel (warning) headaches

due to painful expansion of the

aneurysm or to blood leaking into

2

Neuroimaging may detect them incidentally;

contrast or noncontrast CT can usually

detect AVMs > 1 cm, but the diagnosis is

confirmed with MRI. Occasionally, a cranial

bruit suggests an AVM. Conventional

angiography is required for definitive

diagnosis and determination of whether the

lesion is operable.

Superficial AVMs > 3 cm in diameter are

usually obliterated by a combination of

microsurgery, radiosurgery, and

endovascular surgery. AVMs that are deep

or < 3 cm in diameter are treated with

stereotactic radiosurgery, endovascular

therapy (eg, preresection embolization or

thrombosis via an intra-arterial catheter), or

coagulation with focused proton beam.

Aneurysms: Aneurysms are focal dilations in

arteries. They occur in about 5% of people.

Common contributing factors may include

arteriosclerosis, hypertension, and

hereditary connective tissue disorders (eg,

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, pseudoxanthoma

elasticum, autosomal dominant polycystic

kidney syndrome). Occasionally, septic

emboli cause mycotic aneurysms. Brain

aneurysms are most often < 2.5 cm in

diameter and saccular (noncircumferential);

sometimes they have one or more small,

thin-walled, outpouchings (berry aneurysm).

Most aneurysms occur along the middle or

anterior cerebral arteries or the

communicating branches of the circle of

Willis, particularly at arterial bifurcations.

Mycotic aneurysms usually develop distal to

the first bifurcation of the arterial branches

of the circle of Willis.

the subarachnoid space. Actual

rupture causes a sudden severe

headache called a thunderclap

headache.

Neuroimaging may detect

aneurysms incidentally.

Diagnosis requires angiography, CT

angiography, or magnetic

resonance angiography.

If < 7 mm, asymptomatic aneurysms

in the anterior circulation rarely

rupture and do not warrant the

risks of immediate treatment. They

can be monitored with serial

imaging. If aneurysms are larger,

are in the posterior circulation, or

cause symptoms due to bleeding or

due to compression of neural

structures, endovascular therapy, if

feasible, can be tried

Lobar intracerebral hemorrhages (hematomas in the cerebral lobes, outside the basal

ganglia) usually result from angiopathy due to amyloid deposition in cerebral arteries

(cerebral amyloid angiopathy), which affects primarily the elderly. Lobar hemorrhages may

be multiple and recurrent.

3

Pathophysiology

Blood from an intracerebral hemorrhage accumulates as a mass that can dissect through

and compress adjacent brain tissues, causing neuronal dysfunction. Large hematomas

increase intracranial pressure. Pressure from supratentorial hematomas and the

accompanying edema may cause transtentorial brain herniation, compressing the brain

stem and often causing secondary hemorrhages in the midbrain and pons. If the

hemorrhage ruptures into the ventricular system (intraventricular hemorrhage), blood may

cause acute hydrocephalus. Cerebellar hematomas can expand to block the 4th ventricle,

also causing acute hydrocephalus, or they can dissect into the brain stem. Cerebellar

hematomas that are > 3 cm in diameter may cause midline shift or herniation. Herniation,

midbrain or pontine hemorrhage, intraventricular hemorrhage, acute hydrocephalus, or

dissection into the brain stem can impair consciousness and cause coma and death.

نهاية لالطالع فقط

Symptoms and Signs

Symptoms typically begin with sudden headache, often during activity. However, headache

may be mild or absent in the elderly. Loss of consciousness is common, often within

seconds or a few minutes. Nausea, vomiting, delirium, and focal or generalized seizures are

also common. Neurologic deficits are usually sudden and progressive. Large hemorrhages,

when located in the hemispheres, cause hemiparesis; when located in the posterior fossa,

they cause cerebellar or brain stem deficits (eg, conjugate eye deviation or

ophthalmoplegia, stertorous breathing, pinpoint pupils, coma). Large hemorrhages are fatal

within a few days in about half of patients. In survivors, consciousness returns and

neurologic deficits gradually diminish to various degrees as the extravasated blood is

resorbed. Some patients have surprisingly few neurologic deficits because hemorrhage is

less destructive to brain tissue than infarction.

Small hemorrhages may cause focal deficits without impairment of consciousness and with

minimal or no headache and nausea. Small hemorrhages may mimic ischemic stroke.

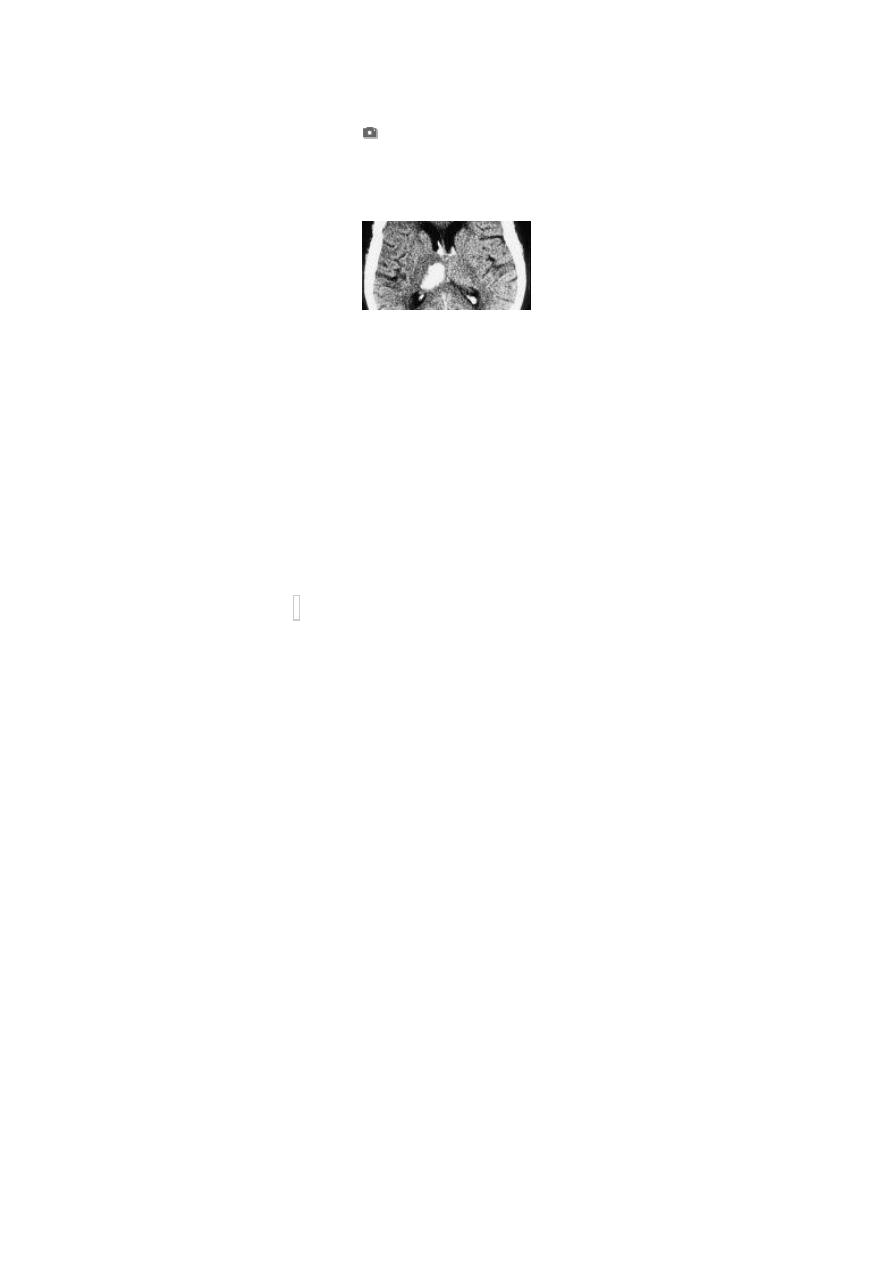

Diagnosis

Neuroimaging

Diagnosis is suggested by sudden onset of headache, focal neurologic deficits, and impaired

consciousness, particularly in patients with risk factors. Intracerebral hemorrhage must be

distinguished from ischemic stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and other causes of acute

neurologic deficits (eg, seizure, hypoglycemia); blood glucose level should be measured at

the bedside immediately.

Immediate CT or MRI is necessary. Neuroimaging is usually diagnostic. If neuroimaging

shows no hemorrhage but subarachnoid hemorrhage is suspected clinically, lumbar

puncture is necessary .CT angiography, done within hours of bleeding onset, may show

areas where contrast extravasates into the clot (spot sign); this finding indicates that

4

bleeding is continuing and suggests that the hematoma will expand and the outcome will

be poor .

Treatment

Supportive measures

Sometimes surgical evacuation (eg, for many cerebellar hematomas >3 cm)

Treatment includes supportive measures and control of modifiable risk factors.

Anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs are contraindicated. If patients have used

anticoagulants, the effects are reversed when possible by giving fresh frozen plasma,

prothrombin complex concentrate, vitamin K, or platelet transfusions as indicated.

Hemodialysis can remove about 60% of dabigatran.

Hypertension should be treated only if mean arterial pressure is > 130 mm Hg or systolic BP

is > 185 mm Hg. Nicardipine

2.5 mg/h IV is given initially; dose is increased by 2.5 mg/h q 5

min to a maximum of 15 mg/h as needed to decrease systolic BP by 10 to 15%.

Cerebellar hemisphere hematomas that are > 3 cm in diameter may cause midline shift or

herniation, so surgical evacuation is often lifesaving. Early evacuation of large lobar cerebral

hematomas may also be lifesaving, but rebleeding occurs frequently, sometimes increasing

neurologic deficits. Early evacuation of deep cerebral hematomas is seldom indicated

because surgical mortality is high and neurologic deficits are usually severe. Anticonvulsants

are not typically used prophylactically; they are used only if patients have had a seizure.