1

Fifth stage

Medicine

Lec-10

د.بشار

15/12/2015

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH)

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is sudden bleeding into the subarachnoid space. The most

common cause of spontaneous bleeding is a ruptured aneurysm. Symptoms include

sudden, severe headache, usually with loss or impairment of consciousness.

Etiology

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is bleeding between the arachnoid and pia mater. Spontaneous

(primary) subarachnoid hemorrhage usually results from ruptured aneurysms. A congenital

intracranial saccular or berry aneurysm is the cause in about 85% of patients. Bleeding may

stop spontaneously. Aneurysmal hemorrhage may occur at any age but is most common

from age 40 to 65.

Less common causes are mycotic aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations, and bleeding

disorders.

Pathophysiology

Blood in the subarachnoid space causes a chemical meningitis that commonly increases

intracranial pressure for days or a few weeks. Secondary vasospasm may cause focal brain

ischemia; about 25% of patients develop signs of a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or

ischemic stroke. Brain edema is maximal and risk of vasospasm and subsequent infarction

(called angry brain) is highest between 72 h and 10 days. Secondary acute hydrocephalus is

also common. A 2nd rupture (rebleeding) sometimes occurs, most often within about 7

days.

Symptoms and Signs

Headache is usually severe, peaking within seconds. Loss of consciousness may follow,

usually immediately but sometimes not for several hours. Severe neurologic deficits may

develop and become irreversible within minutes or a few hours. Sensorium may be

impaired, and patients may become restless. Seizures are possible. Usually, the neck is not

stiff initially unless the cerebellar tonsils herniate. However, within 24 h, chemical

meningitis causes moderate to marked meningismus, vomiting, and sometimes bilateral

extensor plantar responses. Heart or respiratory rate is often abnormal. Fever, continued

headaches, and confusion are common during the first 5 to 10 days. Secondary

hydrocephalus may cause headache, obtundation, and motor deficits that persist for

weeks. Rebleeding may cause recurrent or new symptoms.

Diagnosis

Usually noncontrast CT and, if negative, lumbar puncture

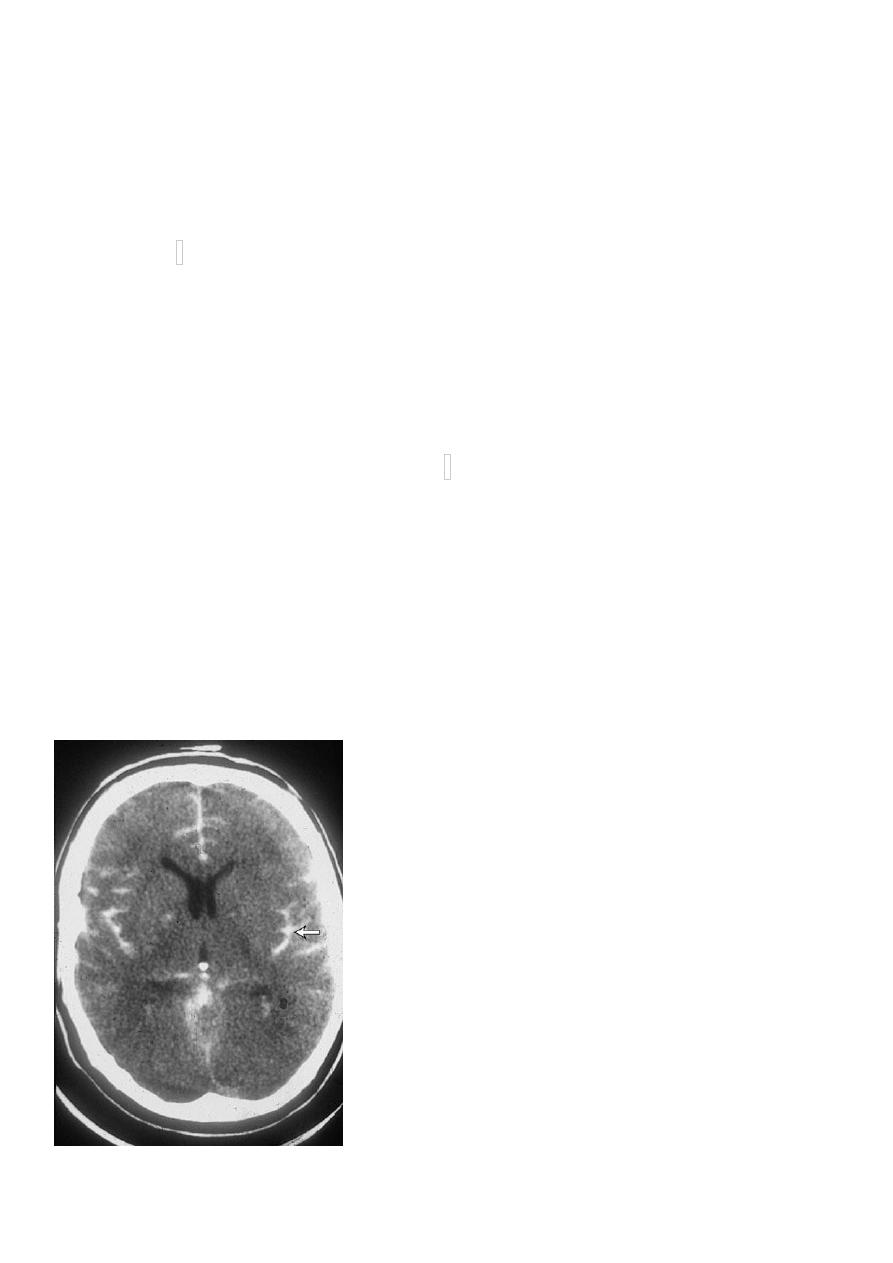

Diagnosis is suggested by characteristic symptoms. Noncontrast CT is > 90% sensitive and is

particularly sensitive if it is done within 6 h of symptom onset. MRI is comparably sensitive

2

but less likely to be immediately available. False-negative results occur if volume of blood is

small or if the patient is so anemic that blood is isodense with brain tissue. If subarachnoid

hemorrhage is suspected clinically but not identified by neuroimaging or if neuroimaging is

not immediately available, lumbar puncture is done .

CSF findings suggesting subarachnoid hemorrhage include numerous RBCs, xanthochromia,

and increased pressure. RBCs in CSF may also be caused by traumatic lumbar puncture.

Traumatic lumbar puncture is suspected if the RBC count decreases in tubes of CSF drawn

sequentially during the same lumbar puncture. About 6 h or more after a subarachnoid

hemorrhage, RBCs become crenated and lyse, resulting in a xanthochromic CSF supernatant

and visible crenated RBCs (noted during microscopic CSF examination); these findings

usually indicate that subarachnoid hemorrhage preceded the lumbar puncture. If there is

still doubt, hemorrhage should be assumed, or the lumbar puncture should be repeated in

8 to 12 h.

In patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage, conventional cerebral angiography is done as

soon as possible after the initial bleeding episode; alternatives include magnetic resonance

angiography and CT angiography. All 4 arteries (2 carotid and 2 vertebral arteries) should be

injected because up to 20% of patients (mostly women) have multiple aneurysms.

On ECG, subarachnoid hemorrhage may cause ST-segment elevation or depression. It can

cause syncope, mimicking MI. Other possible ECG abnormalities include prolongation of the

QRS or QT intervals and peaking or deep, symmetric inversion of T waves.

Prognosis

About 35% of patients die after the first aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage; another

15% die within a few weeks because of a subsequent rupture. After 6 mo, a 2nd rupture

occurs at a rate of about 3%/yr. In general, prognosis is grave with an aneurysm, better

3

with an arteriovenous malformation, and best when 4-vessel angiography does not detect a

lesion, presumably because the bleeding source is small and has sealed itself. Among

survivors, neurologic damage is common, even when treatment is optimal.

Treatment

Treatment in a comprehensive stroke center Nicardipine if mean arterial pressure

is > 130 mm Hg

Nimodipine

to prevent vasospasm

Occlusion of causative aneurysms

Hypertension should be treated only if mean arterial pressure is > 130 mm Hg; euvolemia is

maintained, and IV nicardipine is titrated as for intracerebral hemorrhage .Bed rest is

mandatory. Restlessness and headache are treated symptomatically. Stool softeners are

given to prevent constipation, which can lead to straining. Anticoagulants and antiplatelet

drugs are contraindicated.

Vasospasm is prevented by giving nimodipine

60 mg po q 4 h for 21 days to prevent

vasospasm, but BP needs to be maintained in the desirable range (usually considered to be

a mean arterial pressure of 70 to 130 mm Hg and a systolic pressure of 120 to 185 mm Hg).

If clinical signs of acute hydrocephalus occur, ventricular drainage should be considered.

Aneurysms are occluded to reduce risk of rebleeding. Detachable endovascular coils can be

inserted during angiography to occlude the aneurysm. Alternatively, if the aneurysm is

accessible, surgery to clip the aneurysm or bypass its blood flow can be done, especially for

patients with an evacuable hematoma or acute hydrocephalus