1

Fifth stage

Gynecology

Lec-7

د.سراب

9/3/2016

Pelvic organ prolapse

Definition:

A prolapse is a protrusion of an organ or structure beyond its normal confines.

Prolapses are classified according to their location and the organs contained within them.

Classification:

Anterior vaginal wall prolapse

• Urethrocele: urethral descent

• Cystocele: bladder descent

• Cystourethrocele: descent of bladder and urethra

Posterior vaginal wall prolapse

• Rectocele: rectal descent

• Enterocele: small bowel descent

Apical vaginal prolapse

• Uterovaginal: uterine descent with inversion of vaginal apex

• Vault: post-hysterectomy inversion of vaginal apex

Prevalence:

Pelvic organ prolapse is a very common problem with a prevalence of 41–50 per cent of

women over the age of 40 years.

There is a lifetime risk of 7 per cent of having an operation for prolapse and a lifetime risk

of 11 per cent of having an operation for incontinence or prolapse.

The annual incidence of surgery for POP is within the range of 15–49 cases per 10 000

women years, and it is likely to double in the next 30 years.

Grading:

Three degrees of prolapse are described and the lowest or most dependent portion of the

prolapse is assessed while the patient is straining:

• 1st: descent within the vagina

• 2nd: descent to the introitus

• 3rd: descent outside the introitus.

In the case of uterovaginal prolapse, the most dependent portion of the prolapse is the

cervix, and careful examination can differentiate uterovaginal descent from a long cervix.

Third-degree uterine prolapse is termed ‘procidentia’ and is usually accompanied by

cystourethrocele and rectocele.

2

Aetiology:

The connective tissue, levator ani and intact nerve supply are vital for the maintenance of

position of the pelvic structures, and are influenced by pregnancy, childbirth and ageing.

Whether congenital or acquired, connective tissue defects appear to be important in the

aetiology of prolapse and urinary stress incontinence.

Congenital

Two per cent of symptomatic prolapse occurs in nulliparous women, implying that there

may be a congenital weakness of connective tissue. In addition, genital prolapse is rare in

Afro-Caribbean women, suggesting that genetic differences exist.

Childbirth and raised intra-abdominal pressure

The single major factor leading to the development of genital prolapse appears to be

vaginal delivery. Studies of the levator ani and fascia have shown evidence of nerve and

mechanical damage in women with prolapse, compared to those without, occurring as a

result of vaginal delivery.

Parity is associated with increasing prolapse. The World Health Organization (WHO)

Population Report (1984) suggested that prolapse was up to seven times more common in

women who had more than seven children compared to those who had one. Prolapse

occurring during pregnancy is rare, but is thought to be mediated by the effects of

progesterone and relaxin. In addition, the increase in intra-abdominal pressure will put an

added strain on the pelvic floor and a raised intra-abdominal pressure outside pregnancy

(e.g. chronic cough or constipation) is also a risk factor.

Ageing

The process of ageing can result in loss of collagen and weakness of fascia and connective

tissue. These effects are noted particularly during the post-menopause as a consequence of

oestrogen deficiency.

Postoperative

Poor attention to vaginal vault support at the time of hysterectomy leads to vault prolapse

in approximately 1 per cent of cases. Mechanical displacement as a result of gynaecological

surgery, such as colposuspension, may lead to the development of a rectocele or

enterocele.

3

History:

Women usually present with non-specific symptoms.

Specific symptoms may help to determine the type of prolapse. Aetiological factors should

be enquired about.

Abdominal examination should be performed to exclude organomegaly or abdominopelvic

mass.

Symptoms:

Non-specific:

Lump, local discomfort, backache, bleeding/ infection if ulcerated, dyspareunia or

apareunia.

Rarely, in extremely severe cystourethrocele, uterovaginal or vault prolapse, renal

failure may occur as a result of ureteric kinking.

Specific:

Cystourethrocele urinary frequency and urgency, voiding difficulty, urinary tract

infection, stress incontinence.

Rectocele incomplete bowel emptying, digitation, splinting, passive anal

incontinence.

Vaginal examination:

Prolapse may be obvious when examining the patient in the dorsal position if it

protrudes beyond the introitus; ulceration and/or atrophy may be apparent.

Vaginal pelvic examination should be performed and pelvic mass excluded.

The anterior and posterior vaginal walls and cervical descent should be assessed with

the patient straining in the left lateral position, using a Sims speculum.

Combined rectal and vaginal digital examination can be an aid to differentiate rectocele

from enterocele

Investigations:

There are no essential investigations. If urinary symptoms are present, urine

microscopy, cystometry and cystoscopy should be considered.

The relationship between urinary symptoms and prolapse is complex.

Some women with cystourethrocele have concurrent incontinence; as the prolapse

increases in severity, urethral kinking may restore continence but lead to voiding

difficulty.

Should renal failure be suspected, serum urea and creatinine should be evaluated and

renal ultrasound performed.

For women with symptoms of obstructed defaecation MR proctography can help

diagnose a rectocele.

4

Differential diagnosis:

Anterior wall prolapse: congenital or inclusion dermoid vaginal cyst, urethral

diverticulum.

Uterovaginal prolapse: large uterine polyp.

Treatment:

The choice of treatment depends on the patient’s wishes, level of fitness and desire to

preserve coital function.

Prior to specific treatment, attempts should be made to correct obesity, chronic cough or

constipation. If the prolapse is ulcerated, a 7-day course of topical oestrogen should be

administered.

Prevention:

Shortening the second stage of delivery and reducing traumatic delivery may result in fewer

women developing a prolapse.

The benefits of episiotomy and hormone replacement therapy at the menopause have not

been substantiated.

Medical:

If a woman is found to have uterovaginal prolapse on examination but has no

symptoms, then it would be inappropriate to offer any surgical treatment and either

observation or conservative therapy would be best.

If symptoms are mild, then pelvic floor physiotherapy is offered but there are no

randomized controlled trials examining the effectiveness of physiotherapy on prolapse.

Silicon rubber-based ring pessaries are the most popular form of conservative therapy.

They are inserted into the vagina in much the same way as a contraceptive diaphragm

and need replacement at annual intervals.

Shelf pessaries are rarely used but may be useful in women who cannot retain a ring

pessary.

The use of pessaries can be complicated by vaginal ulceration and infection.

The vagina should therefore be carefully inspected at the time of replacement.

There are a whole range of newer pessaries that are undergoing evaluation and these

may be more comfortable for the patient.

Indications for pessary treatment are:

patient’s wish;

as a therapeutic test;

childbearing not complete;

medically unfit;

during and after pregnancy (awaiting involution);

while awaiting surgery.

5

Surgery:

The aim of surgical repair is to restore anatomy and function.

There are vaginal and abdominal operations designed to correct prolapse, and choice often

depends on a woman’s desire to preserve coital function.

1- Cystourethrocele

Anterior repair (colporrhaphy) is the most commonly performed surgical procedure but

should be avoided if there is concurrent stress incontinence.

An anterior vaginal wall incision is made and the fascial defect allowing the bladder to

herniate through is identified and closed. With the bladder position restored, any

redundant vaginal epithelium is excised and the incision closed.

2- Rectocele

Posterior repair (colporrhaphy) is the most commonly performed procedure.

A posterior vaginal wall incision is made and the fascial defect allowing the rectum to

herniate through is identified and closed.

With the rectal position restored, any redundant vaginal epithelium is excised and the

incision closed.

3- Enterocele

The surgical principles are similar to those of anterior and posterior repair, but the

peritoneal sac containing the small bowel should be excised.

In addition, the pouch of Douglas is closed by approximating the peritoneum and/or the

uterosacral ligaments.

4- Uterovaginal prolapse

Uterine preserving surgery:

Uterine preserving surgery is used largely when a woman still wants to have further

children and therefore the uterus has to be preserved. Occasionally, a woman wishes to

preserve her uterus and then may choose this option:

o Hysterosacropexy

o The Manchester repair

o Le Fort colpocleisis

o ‘Total mesh’ procedure using an introducer device

Procedures involving hysterectomy:

o These procedures involve removal of the uterus:

o Vaginal hysterectomy

o Total abdominal hysterectomy and sacrocolpopexy

o Subtotal abdominal hysterectomy and sacrocervicopexy

5- Vault prolapse

Sacrocolpopexy is similar tosacrohysteropexy but the inverted vaginal vault is attached to

the sacrum using a mesh and the pouch of Douglas is closed. Sacrospinous ligament fixation

is a vaginal procedure in which the vault is sutured to one or other sacrospinous ligament.

6

Key points:

• A prolapse is a protrusion of an organ or structure beyond its normal confines;

prolapses are extremely common in multiparous women.

• Damage to the major supports of the vagina, i.e. ligaments, fascia and levator ani

muscles, leads to prolapse.

• Childbirth injury is the major aetiological factor.

• Most women with prolapse present with non-specific symptoms, such as a lump and

backache.

• Women with cystourethrocele often have urinary symptoms.

• Women with rectocele often have bowel symptoms.

• Diagnosis is made by clinical examination.

• Surgery is the mainstay of treatment.

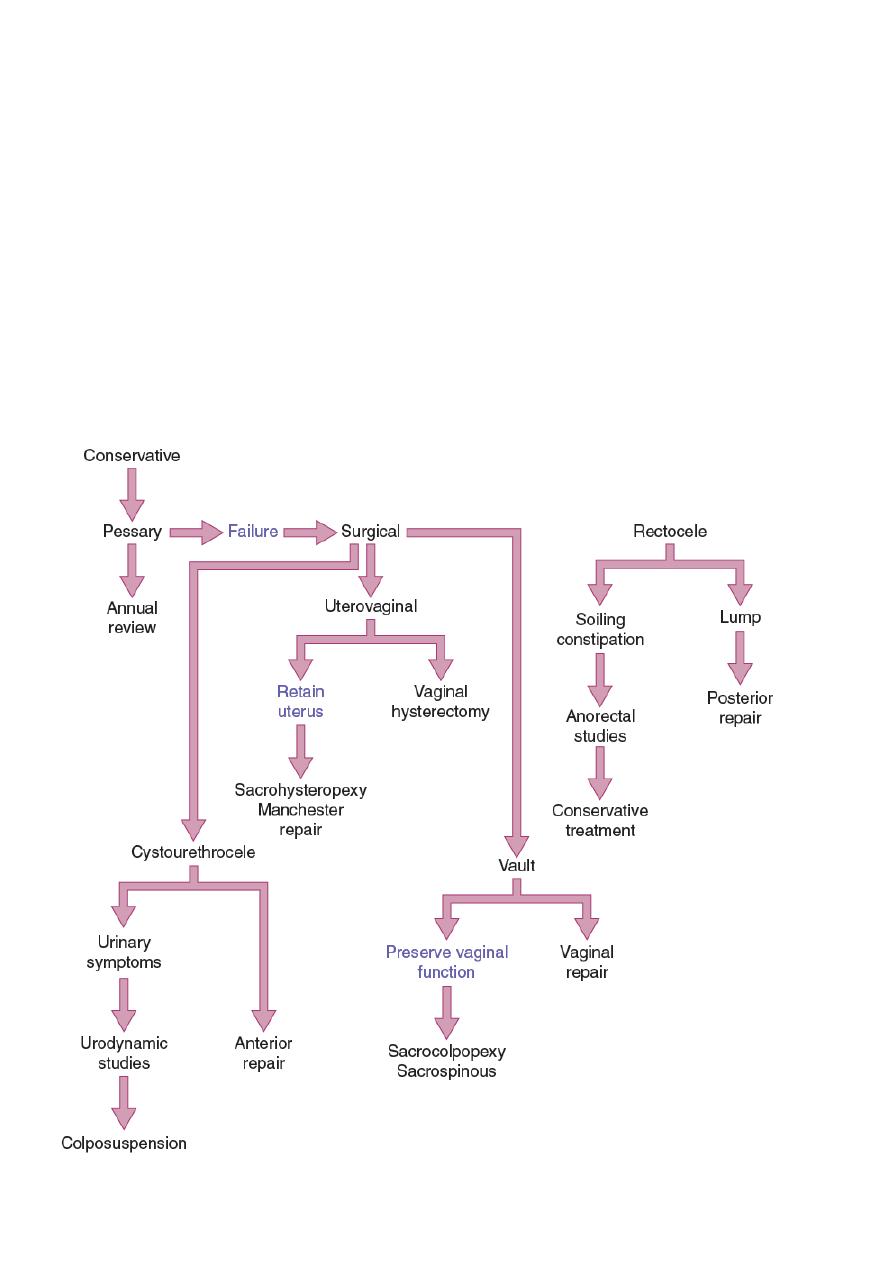

Treatment of prolapse: